Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Sanger sequencing

View on WikipediaSanger sequencing is a method of DNA sequencing that involves electrophoresis and is based on the random incorporation of chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides by DNA polymerase during in vitro DNA replication. After first being developed by Frederick Sanger and colleagues in 1977, it became the most widely used sequencing method for approximately 40 years. An automated instrument using slab gel electrophoresis and fluorescent labels was first commercialized by Applied Biosystems in March 1987.[1] Later, automated slab gels were replaced with automated capillary array electrophoresis.[2]

Recently, higher volume Sanger sequencing has been replaced by next generation sequencing methods, especially for large-scale, automated genome analyses. However, the Sanger method remains in wide use for smaller-scale projects and for validation of deep sequencing results. It still has the advantage over short-read sequencing technologies (like Illumina) in that it can produce DNA sequence reads of > 500 nucleotides and maintains a very low error rate with accuracies around 99.99%.[3] Sanger sequencing is still actively being used in efforts for public health initiatives such as sequencing the spike protein from SARS-CoV-2[4] as well as for the surveillance of norovirus outbreaks through the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)'s CaliciNet surveillance network.[5]

Method

[edit]

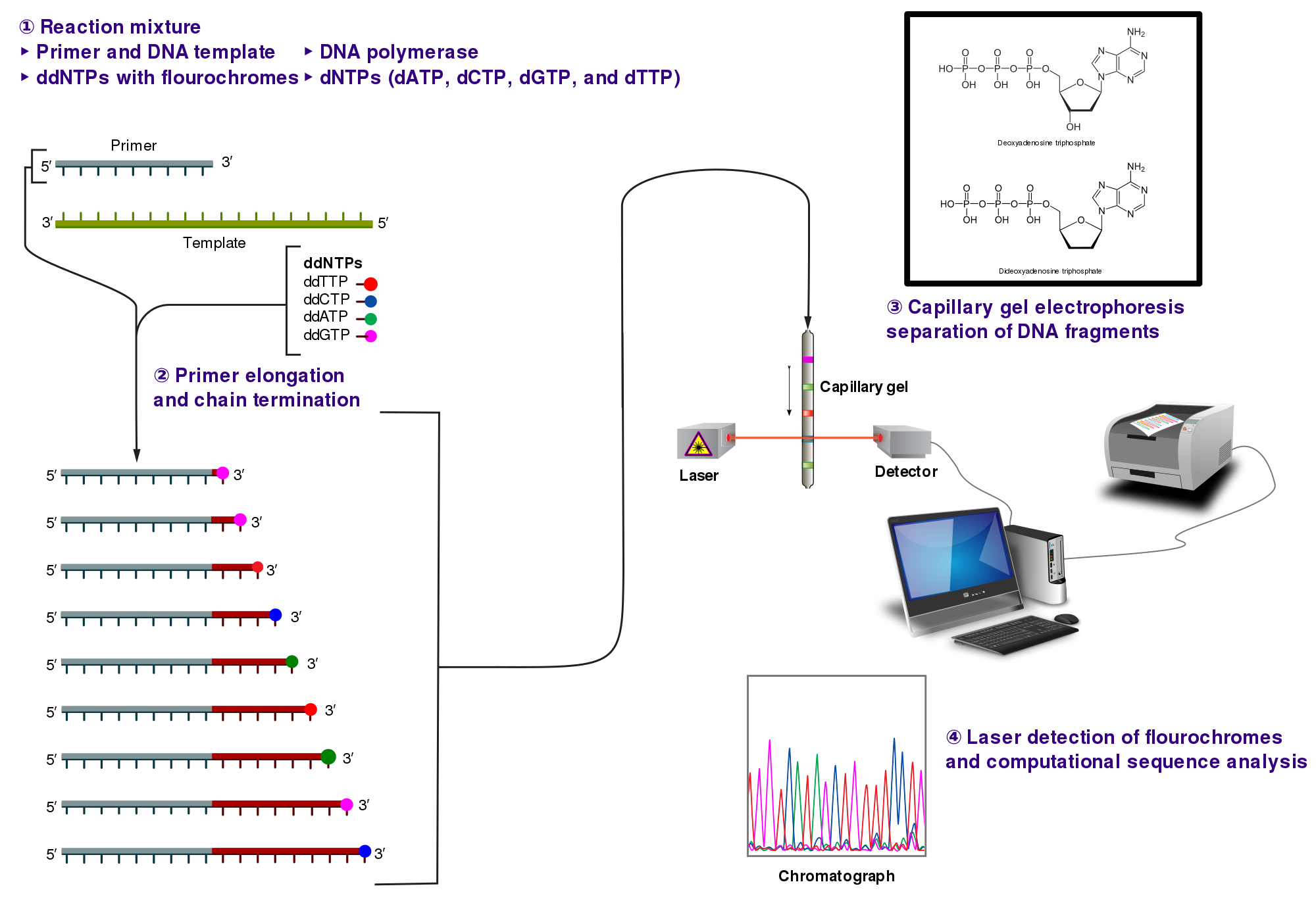

The classical chain-termination method requires a single-stranded DNA template, a DNA primer, a DNA polymerase, normal deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), and modified di-deoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddNTPs), the latter of which terminate DNA strand elongation. These chain-terminating nucleotides lack a 3'-OH group required for the formation of a phosphodiester bond between two nucleotides, causing DNA polymerase to cease extension of DNA when a modified ddNTP is incorporated. The ddNTPs may be radioactively or fluorescently labelled for detection in automated sequencing machines.

The DNA sample is divided into four separate sequencing reactions, containing all four of the standard deoxynucleotides (dATP, dGTP, dCTP and dTTP) and the DNA polymerase. To each reaction is added only one of the four dideoxynucleotides (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, or ddTTP), while the other added nucleotides are ordinary ones. The deoxynucleotide concentration should be approximately 100-fold higher than that of the corresponding dideoxynucleotide (e.g. 0.5mM dTTP : 0.005mM ddTTP) to allow enough fragments to be produced while still transcribing the complete sequence (but the concentration of ddNTP also depends on the desired length of sequence).[6] Putting it in a more sensible order, four separate reactions are needed in this process to test all four ddNTPs. Following rounds of template DNA extension from the bound primer, the resulting DNA fragments are heat denatured and separated by size using gel electrophoresis. In the original publication of 1977,[6] the formation of base-paired loops of ssDNA was a cause of serious difficulty in resolving bands at some locations. This is frequently performed using a denaturing polyacrylamide-urea gel with each of the four reactions run in one of four individual lanes (lanes A, T, G, C). The DNA bands may then be visualized by autoradiography or UV light, and the DNA sequence can be directly read off the X-ray film or gel image.

In the image on the right, X-ray film was exposed to the gel, and the dark bands correspond to DNA fragments of different lengths. A dark band in a lane indicates a DNA fragment that is the result of chain termination after incorporation of a dideoxynucleotide (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, or ddTTP). The relative positions of the different bands among the four lanes, from bottom to top, are then used to read the DNA sequence.

Technical variations of chain-termination sequencing include tagging with nucleotides containing radioactive phosphorus for radiolabelling, or using a primer labeled at the 5' end with a fluorescent dye. Dye-primer sequencing facilitates reading in an optical system for faster and more economical analysis and automation. The later development by Leroy Hood and coworkers[7][8] of fluorescently labeled ddNTPs and primers set the stage for automated, high-throughput DNA sequencing.

Chain-termination methods have greatly simplified DNA sequencing. For example, chain-termination-based kits are commercially available that contain the reagents needed for sequencing, pre-aliquoted and ready to use. Limitations include non-specific binding of the primer to the DNA, affecting accurate read-out of the DNA sequence, and DNA secondary structures affecting the fidelity of the sequence.

Dye-terminator sequencing

[edit]

Dye-terminator sequencing utilizes labelling of the chain terminator ddNTPs, which permits sequencing in a single reaction rather than four reactions as in the labelled-primer method. In dye-terminator sequencing, each of the four dideoxynucleotide chain terminators is labelled with fluorescent dyes, each of which emits light at different wavelengths.

Owing to its greater expediency and speed, dye-terminator sequencing is now the mainstay in automated sequencing. Its limitations include dye effects due to differences in the incorporation of the dye-labelled chain terminators into the DNA fragment, resulting in unequal peak heights and shapes in the electronic DNA sequence trace electropherogram (a type of chromatogram) after capillary electrophoresis (see figure to the left).

This problem has been addressed with the use of modified DNA polymerase enzyme systems and dyes that minimize incorporation variability, as well as methods for eliminating "dye blobs". The dye-terminator sequencing method, along with automated high-throughput DNA sequence analyzers, was used for the vast majority of sequencing projects until the introduction of next generation sequencing.

Automation and sample preparation

[edit]

Automated DNA-sequencing instruments (DNA sequencers) can sequence up to 384 DNA samples in a single batch. Batch runs may occur up to 24 times a day. DNA sequencers separate strands by size (or length) using capillary electrophoresis, they detect and record dye fluorescence, and output data as fluorescent peak trace chromatograms. Sequencing reactions (thermocycling and labelling), cleanup and re-suspension of samples in a buffer solution are performed separately, before loading samples onto the sequencer. A number of commercial and non-commercial software packages can trim low-quality DNA traces automatically. These programs score the quality of each peak and remove low-quality base peaks (which are generally located at the ends of the sequence).[9] The accuracy of such algorithms is inferior to visual examination by a human operator, but is adequate for automated processing of large sequence data sets.

Applications of dye-terminating sequencing

[edit]The field of public health plays many roles to support patient diagnostics as well as environmental surveillance of potential toxic substances and circulating biological pathogens. Public health laboratories (PHL) and other laboratories around the world have played a pivotal role in providing rapid sequencing data for the surveillance of the virus SARS-CoV-2, causative agent for COVID-19, during the pandemic that was declared a public health emergency on January 30, 2020.[10] Laboratories were tasked with the rapid implementation of sequencing methods and asked to provide accurate data to assist in the decision-making models for the development of policies to mitigate spread of the virus. Many laboratories resorted to next generation sequencing methodologies while others supported efforts with Sanger sequencing. The sequencing efforts of SARS-CoV-2 are many, while most laboratories implemented whole genome sequencing of the virus, others have opted to sequence very specific genes of the virus such as the S-gene, encoding the information needed to produce the spike protein. The high mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2 leads to genetic differences within the S-gene and these differences have played a role in the infectivity of the virus.[11] Sanger sequencing of the S-gene provides a quick, accurate, and more affordable method to retrieving the genetic code. Laboratories in lower income countries may not have the capabilities to implement expensive applications such as next generation sequencing, so Sanger methods may prevail in supporting the generation of sequencing data for surveillance of variants.

Sanger sequencing is also the "gold standard" for norovirus surveillance methods for the Center for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) CaliciNet network. CalciNet is an outbreak surveillance network that was established in March 2009. The goal of the network is to collect sequencing data of circulating noroviruses in the United States and activate downstream action to determine the source of infection to mitigate the spread of the virus. The CalciNet network has identified many infections as foodborne illnesses.[5] This data can then be published and used to develop recommendations for future action to prevent tainting food. The methods employed for detection of norovirus involve targeted amplification of specific areas of the genome. The amplicons are then sequenced using dye-terminating Sanger sequencing and the chromatograms and sequences generated are analyzed with a software package developed in BioNumerics. Sequences are tracked and strain relatedness is studied to infer epidemiological relevance.

Challenges

[edit]Common challenges of DNA sequencing with the Sanger method include poor quality in the first 15–40 bases of the sequence due to primer binding and deteriorating quality of sequencing traces after 700–900 bases. Base calling software such as Phred typically provides an estimate of quality to aid in trimming of low-quality regions of sequences.[12][13]

In cases where DNA fragments are cloned before sequencing, the resulting sequence may contain parts of the cloning vector. In contrast, PCR-based cloning and next-generation sequencing technologies based on pyrosequencing often avoid using cloning vectors. Recently, one-step Sanger sequencing (combined amplification and sequencing) methods such as Ampliseq and SeqSharp have been developed that allow rapid sequencing of target genes without cloning or prior amplification.[14][15]

Current methods can directly sequence only relatively short (300–1000 nucleotides long) DNA fragments in a single reaction. The main obstacle to sequencing DNA fragments above this size limit is insufficient power of separation for resolving large DNA fragments that differ in length by only one nucleotide.

Microfluidic Sanger sequencing

[edit]Microfluidic Sanger sequencing is a lab-on-a-chip application for DNA sequencing, in which the Sanger sequencing steps (thermal cycling, sample purification, and capillary electrophoresis) are integrated on a wafer-scale chip using nanoliter-scale sample volumes. This technology generates long and accurate sequence reads, while obviating many of the significant shortcomings of the conventional Sanger method (e.g. high consumption of expensive reagents, reliance on expensive equipment, personnel-intensive manipulations, etc.) by integrating and automating the Sanger sequencing steps.

In its modern inception, high-throughput genome sequencing involves fragmenting the genome into small single-stranded pieces, followed by amplification of the fragments by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Adopting the Sanger method, each DNA fragment is irreversibly terminated with the incorporation of a fluorescently labeled dideoxy chain-terminating nucleotide, thereby producing a DNA "ladder" of fragments that each differ in length by one base and bear a base-specific fluorescent label at the terminal base. Amplified base ladders are then separated by capillary array electrophoresis (CAE) with automated, in situ "finish-line" detection of the fluorescently labeled ssDNA fragments, which provides an ordered sequence of the fragments. These sequence reads are then computer assembled into overlapping or contiguous sequences (termed "contigs") which resemble the full genomic sequence once fully assembled.[16]

Sanger methods achieve maximum read lengths of approximately 800 bp (typically 500–600 bp with non-enriched DNA). The longer read lengths in Sanger methods display significant advantages over other sequencing methods especially in terms of sequencing repetitive regions of the genome. A challenge of short-read sequence data is particularly an issue in sequencing new genomes (de novo) and in sequencing highly rearranged genome segments, typically those seen of cancer genomes or in regions of chromosomes that exhibit structural variation.[17]

Applications of microfluidic sequencing technologies

[edit]Other useful applications of DNA sequencing include single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) detection, single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) heteroduplex analysis, and short tandem repeat (STR) analysis. Resolving DNA fragments according to differences in size and/or conformation is the most critical step in studying these features of the genome.[16]

Device design

[edit]The sequencing chip has a four-layer construction, consisting of three 100-mm-diameter glass wafers (on which device elements are microfabricated) and a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membrane. Reaction chambers and capillary electrophoresis channels are etched between the top two glass wafers, which are thermally bonded. Three-dimensional channel interconnections and microvalves are formed by the PDMS and bottom manifold glass wafer.

The device consists of three functional units, each corresponding to the Sanger sequencing steps. The thermal cycling (TC) unit is a 250-nanoliter reaction chamber with integrated resistive temperature detector, microvalves, and a surface heater. Movement of reagent between the top all-glass layer and the lower glass-PDMS layer occurs through 500-μm-diameter via-holes. After thermal-cycling, the reaction mixture undergoes purification in the capture/purification chamber, and then is injected into the capillary electrophoresis (CE) chamber. The CE unit consists of a 30-cm capillary which is folded into a compact switchback pattern via 65-μm-wide turns.

Sequencing chemistry

[edit]- Thermal cycling

- In the TC reaction chamber, dye-terminator sequencing reagent, template DNA, and primers are loaded into the TC chamber and thermal-cycled for 35 cycles ( at 95 °C for 12 seconds and at 60 °C for 55 seconds).

- Purification

- The charged reaction mixture (containing extension fragments, template DNA, and excess sequencing reagent) is conducted through a capture/purification chamber at 30 °C via a 33-Volts/cm electric field applied between capture outlet and inlet ports. The capture gel through which the sample is driven, consists of 40 μM of oligonucleotide (complementary to the primers) covalently bound to a polyacrylamide matrix. Extension fragments are immobilized by the gel matrix, and excess primer, template, free nucleotides, and salts are eluted through the capture waste port. The capture gel is heated to 67–75 °C to release extension fragments.

- Capillary electrophoresis

- Extension fragments are injected into the CE chamber where they are electrophoresed through a 125-167-V/cm field.

Platforms

[edit]The Apollo 100 platform (Microchip Biotechnologies Inc., Dublin, California)[18] integrates the first two Sanger sequencing steps (thermal cycling and purification) in a fully automated system. The manufacturer claims that samples are ready for capillary electrophoresis within three hours of the sample and reagents being loaded into the system. The Apollo 100 platform requires sub-microliter volumes of reagents.

Comparisons to other sequencing techniques

[edit]| Technology | Number of lanes | Injection volume (nL) | Analysis time | Average read length | Throughput (including analysis; Mb/h) | Gel pouring | Lane tracking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slab gel | 96 | 500–1000 | 6–8 hours | 700 bp | 0.0672 | Yes | Yes |

| Capillary array electrophoresis | 96 | 1–5 | 1–3 hours | 700 bp | 0.166 | No | No |

| Microchip | 96 | 0.1–0.5 | 6–30 minutes | 430 bp | 0.660 | No | No |

| 454/Roche FLX (2008) | < 0.001 | 4 hours | 200–300 bp | 20–30 | |||

| Illumina/Solexa (2008) | 2–3 days | 30–100 bp | 20 | ||||

| ABI/SOLiD (2008) | 8 days | 35 bp | 5–15 | ||||

| Illumina MiSeq (2019) | 1–3 days | 2x75–2x300 bp | 170–250 | ||||

| Illumina NovaSeq (2019) | 1–2 days | 2x50–2x150 bp | 22,000–67,000 | ||||

| Ion Torrent Ion 530 (2019) | 2.5–4 hours | 200–600 bp | 110–920 | ||||

| BGI MGISEQ-T7 (2019) | 1 day | 2x150 bp | 250,000 | ||||

| Pacific Biosciences Revio (2023) | 12–30 hours | 15–25 kb[21] | 15,000 | ||||

| Oxford Nanopore MinIon (2019) | 3 days | 13–20 kb[22] | 700 |

The ultimate goal of high-throughput sequencing is to develop systems that are low-cost, and extremely efficient at obtaining extended (longer) read lengths. Longer read lengths of each single electrophoretic separation, substantially reduces the cost associated with de novo DNA sequencing and the number of templates needed to sequence DNA contigs at a given redundancy. Microfluidics may allow for faster, cheaper and easier sequence assembly.[16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chait, Edward; Page, Guy; Hunkapiller, Michael (1988). "Battle of the DNA sequencers". Nature. 333 (6172): 477–478. Bibcode:1988Natur.333..477C. doi:10.1038/333477a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Zhang, J (1999-12-15). "A multiple-capillary electrophoresis system for small-scale DNA sequencing and analysis". Nucleic Acids Research. 27 (24): 36e–36. doi:10.1093/nar/27.24.e36. PMC 148759. PMID 10572188.

- ^ Shendure J, Ji H (October 2008). "Next-generation DNA sequencing". Nature Biotechnology. 26 (10): 1135–1145. doi:10.1038/nbt1486. PMID 18846087. S2CID 6384349.

- ^ Daniels RS, Harvey R, Ermetal B, Xiang Z, Galiano M, Adams L, McCauley JW (November 2021). "A Sanger sequencing protocol for SARS-CoV-2 S-gene". Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses. 15 (6): 707–710. doi:10.1111/irv.12892. PMC 8447197. PMID 34346163.

- ^ a b Vega E, Barclay L, Gregoricus N, Williams K, Lee D, Vinjé J (August 2011). "Novel surveillance network for norovirus gastroenteritis outbreaks, United States". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 17 (8): 1389–1395. doi:10.3201/eid1708.101837. PMC 3381557. PMID 21801614.

- ^ a b Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR (December 1977). "DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 74 (12): 5463–5467. Bibcode:1977PNAS...74.5463S. doi:10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. PMC 431765. PMID 271968.

- ^ Smith LM, Sanders JZ, Kaiser RJ, Hughes P, Dodd C, Connell CR, et al. (1986). "Fluorescence detection in automated DNA sequence analysis". Nature. 321 (6071): 674–679. Bibcode:1986Natur.321..674S. doi:10.1038/321674a0. PMID 3713851. S2CID 27800972.

We have developed a method for the partial automation of DNA sequence analysis. Fluorescence detection of the DNA fragments is accomplished by means of a fluorophore covalently attached to the oligonucleotide primer used in enzymatic DNA sequence analysis. A different coloured fluorophore is used for each of the reactions specific for the bases A, C, G and T. The reaction mixtures are combined and co-electrophoresed down a single polyacrylamide gel tube, the separated fluorescent bands of DNA are detected near the bottom of the tube, and the sequence information is acquired directly by computer.

- ^ Smith LM, Fung S, Hunkapiller MW, Hunkapiller TJ, Hood LE (April 1985). "The synthesis of oligonucleotides containing an aliphatic amino group at the 5' terminus: synthesis of fluorescent DNA primers for use in DNA sequence analysis". Nucleic Acids Research. 13 (7): 2399–2412. doi:10.1093/nar/13.7.2399. PMC 341163. PMID 4000959.

- ^ Crossley, Beate M.; Bai, Jianfa; Glaser, Amy; Maes, Roger; Porter, Elizabeth; Killian, Mary Lea; Clement, Travis; Toohey-Kurth, Kathy (November 2020). "Guidelines for Sanger sequencing and molecular assay monitoring". Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 32 (6): 767–775. doi:10.1177/1040638720905833. ISSN 1040-6387. PMC 7649556. PMID 32070230.

- ^ Taylor DB (2021-03-17). "A Timeline of the Coronavirus Pandemic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-12-05.

- ^ Sanches PR, Charlie-Silva I, Braz HL, Bittar C, Freitas Calmon M, Rahal P, Cilli EM (September 2021). "Recent advances in SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein and RBD mutations comparison between new variants Alpha (B.1.1.7, United Kingdom), Beta (B.1.351, South Africa), Gamma (P.1, Brazil) and Delta (B.1.617.2, India)". Journal of Virus Eradication. 7 (3) 100054. doi:10.1016/j.jve.2021.100054. PMC 8443533. PMID 34548928.

- ^ "Phred – Quality Base Calling". Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- ^ Ledergerber C, Dessimoz C (September 2011). "Base-calling for next-generation sequencing platforms". Briefings in Bioinformatics. 12 (5): 489–497. doi:10.1093/bib/bbq077. PMC 3178052. PMID 21245079.

- ^ Murphy KM, Berg KD, Eshleman JR (January 2005). "Sequencing of genomic DNA by combined amplification and cycle sequencing reaction". Clinical Chemistry. 51 (1): 35–39. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2004.039164. PMID 15514094.

- ^ SenGupta DJ, Cookson BT (May 2010). "SeqSharp: A general approach for improving cycle-sequencing that facilitates a robust one-step combined amplification and sequencing method". The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 12 (3): 272–277. doi:10.2353/jmoldx.2010.090134. PMC 2860461. PMID 20203000.

- ^ a b c Kan CW, Fredlake CP, Doherty EA, Barron AE (November 2004). "DNA sequencing and genotyping in miniaturized electrophoresis systems". Electrophoresis. 25 (21–22): 3564–3588. doi:10.1002/elps.200406161. PMID 15565709. S2CID 4851728.

- ^ a b Morozova O, Marra MA (November 2008). "Applications of next-generation sequencing technologies in functional genomics". Genomics. 92 (5): 255–264. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.07.001. PMID 18703132.

- ^ Microchip Biologies Inc. Apollo 100

- ^ Sinville R, Soper SA (July 2007). "High resolution DNA separations using microchip electrophoresis". Journal of Separation Science. 30 (11): 1714–1728. doi:10.1002/jssc.200700150. PMID 17623451.

- ^ Kumar KR, Cowley MJ, Davis RL (October 2019). "Next-Generation Sequencing and Emerging Technologies". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 45 (7): 661–673. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1688446. PMID 31096307.

- ^ Mastrorosa FK, Miller DE, Eichler EE (June 2023). "Applications of long-read sequencing to Mendelian genetics". Genome Medicine. 15 (1): 42. doi:10.1186/s13073-023-01194-3. PMC 10266321. PMID 37316925.

- ^ Tyson JR, O'Neil NJ, Jain M, Olsen HE, Hieter P, Snutch TP (February 2018). "MinION-based long-read sequencing and assembly extends the Caenorhabditis elegans reference genome". Genome Research. 28 (2): 266–274. doi:10.1101/gr.221184.117. PMC 5793790. PMID 29273626.

Further reading

[edit]- Dewey FE, Pan S, Wheeler MT, Quake SR, Ashley EA (February 2012). "DNA sequencing: clinical applications of new DNA sequencing technologies". Circulation. 125 (7): 931–944. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.972828. PMC 3364518. PMID 22354974.

- Sanger F, Coulson AR, Barrell BG, Smith AJ, Roe BA (October 1980). "Cloning in single-stranded bacteriophage as an aid to rapid DNA sequencing". Journal of Molecular Biology. 143 (2): 161–178. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(80)90196-5. PMID 6260957.

External links

[edit]Sanger sequencing

View on GrokipediaHistory and Development

Original 1977 Method

The original 1977 Sanger sequencing method, known as dideoxy chain-termination sequencing, represented a significant advancement over the laboratory's prior "plus and minus" technique, which had been introduced in 1975 and relied on selective omission or addition of nucleotides to generate partial sequences but suffered from inconsistent band patterns and limited readability beyond 100-200 bases. In the new approach, chain termination was achieved through the incorporation of 2',3'-dideoxynucleoside triphosphates (ddNTPs) and arabinonucleoside triphosphates (araNTPs), synthetic analogs lacking a 3'-hydroxyl group, which prevented further elongation once incorporated by DNA polymerase.[1] This method employed the Klenow fragment of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I, a large proteolytic fragment with 5'→3' polymerase activity but lacking 5'→3' exonuclease function, allowing controlled synthesis on single-stranded DNA templates. The protocol began with preparation of a single-stranded DNA template, typically derived from bacteriophage φX174 circular DNA, which was denatured if necessary to ensure single-stranded form. A short oligonucleotide primer, complementary to a known region of the template, was 5'-end-labeled with γ-[³²P]ATP using T4 polynucleotide kinase for subsequent detection. The labeled primer was annealed to the template by heating to 100°C and cooling slowly in the presence of a buffer containing Mg²⁺. Four separate in vitro DNA synthesis reactions were then performed in parallel: each included the annealed template-primer (0.2 pmol template, 1 pmol primer), Klenow fragment (2-5 units), all four deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP at 40-150 μM each, adjusted for balanced incorporation), and one type of ddNTP (ddATP, ddCTP, ddGTP, or ddTTP at 0.3-1 μM) specific to that reaction tube, corresponding to the A-, C-, G-, or T-terminating lanes, respectively. Incubation occurred at 37°C for 15-60 minutes, generating a population of radiolabeled DNA fragments of all lengths terminating at positions where the complementary ddNTP was incorporated. Reactions were terminated with EDTA, and unincorporated nucleotides were removed if needed via ethanol precipitation or gel filtration. The chain-terminated fragments from each reaction were loaded into adjacent lanes of a denaturing polyacrylamide gel (typically 4-8% acrylamide cross-linked with bis-acrylamide, containing 7 M urea to fully denature secondary structures) and subjected to electrophoresis at 1000-2000 V in a buffer system like Tris-borate-EDTA, with 40 cm-long plates allowing resolution of fragments up to ~250 bases. Gels were dried and exposed to X-ray film for autoradiography, revealing a ladder of bands where the position and intensity indicated the sequence. By aligning bands across the four lanes (A, C, G, T), the complementary DNA sequence was read from shortest to longest fragments, starting from the primer. This setup enabled reliable sequencing of up to 150-200 bases per run with high accuracy. The method was validated by sequencing segments of the bacteriophage φX174 genome. The complete 5,386-nucleotide sequence of φX174 had been determined earlier that year using the plus and minus method, marking the first full DNA genome sequenced, with the chain-termination approach providing a more efficient and accurate alternative.[10][1] Published in the seminal paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the technique's precision and scalability indirectly paved the way for ambitious projects like the Human Genome Project by establishing a robust framework for enzymatic DNA sequencing.Key Milestones and Recognition

Following the development of the original chain-termination method in 1977, Frederick Sanger received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1980 for his contributions to determining the base sequences in nucleic acids, shared with Walter Gilbert for their contributions to the determination of base sequences in nucleic acids and Paul Berg for his fundamental studies, both theoretical and experimental, on the biochemistry of nucleic acids, with particular regard to recombinant-DNA.[5] This was Sanger's second Nobel Prize, having earlier earned the 1958 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on the structure of proteins, particularly insulin. These awards recognized the transformative impact of Sanger's sequencing innovations on molecular biology. In the 1980s, key advancements enhanced the efficiency and automation of Sanger sequencing. In 1986, researchers introduced fluorescence detection for automated DNA sequence analysis, using a fluorophore attached to the primer to enable laser-based reading of separated fragments, significantly improving throughput over manual radioactive methods.[11] Thermal cycling was also incorporated around this time to linearize amplification similar to PCR, reducing template requirements and simplifying reactions. By 1988, the use of thermostable Taq DNA polymerase from Thermus aquaticus further enabled robust cycle sequencing protocols, allowing repeated denaturation and extension without enzyme degradation, as demonstrated by Innis et al. for sequencing and direct sequencing of PCR-amplified DNA.[12] Seminal publications included Smith et al.'s 1986 work on fluorescence-based automation and Innis et al.'s 1988 demonstration of Taq polymerase in cycle sequencing. The 1990s brought widespread automation through commercial systems like the ABI PRISM series from Applied Biosystems, introduced in the mid-1990s, which integrated capillary electrophoresis and fluorescent dye-terminator chemistry for high-throughput processing. These innovations were pivotal for the Human Genome Project (HGP), an international effort launched in 1990 that successfully sequenced approximately 3 billion base pairs of the human genome by 2003, two years ahead of schedule, largely due to the scalability of automated Sanger sequencing. Another key publication was Prober et al.'s 1987 paper on fluorescent chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides, which laid the groundwork for dye-based detection in these systems.[13] Although Sanger sequencing dominated for decades, its use declined after 2005 with the rise of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, such as the 454 GS FLX platform, which offered massively parallel processing at lower costs per base. However, Sanger sequencing experienced a resurgence in the 2020s for targeted applications, including validation of NGS results and precise tracking of SARS-CoV-2 variants during the COVID-19 pandemic, where it provided reliable confirmation of mutations in clinical samples.[14]Fundamental Principles

Chain-Termination Mechanism

The chain-termination mechanism of Sanger sequencing exploits the biochemical properties of DNA polymerase to produce a series of DNA fragments terminated at specific nucleotide positions, enabling the determination of the sequence order. In this process, a single-stranded DNA template is annealed to a synthetic primer, and DNA polymerase initiates synthesis by incorporating complementary deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs: dATP, dGTP, dCTP, dTTP). Each dNTP possesses a 3'-hydroxyl (OH) group on its deoxyribose sugar, which forms a phosphodiester bond with the next incoming nucleotide, allowing continuous chain extension. However, when a dideoxynucleoside triphosphate (ddNTP) is incorporated instead, the absence of the 3'-OH group blocks further elongation, terminating the growing strand at that point. This selective termination was first described by Frederick Sanger and colleagues in their seminal 1977 paper, where they utilized E. coli DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment) for its lack of 5'-3' exonuclease activity, ensuring precise extension without template degradation. The reaction mixture for each termination includes the single-stranded DNA template, primer, DNA polymerase, all four dNTPs, and a limited amount of one ddNTP type to achieve random incorporation. The ddNTP is present at a low concentration relative to the complementary dNTP, typically in a ratio of 1:100 to 1:200 (ddNTP:dNTP), which promotes infrequent termination and generates a diverse population of fragments statistically distributed across possible lengths. Four parallel reactions are conducted separately—one for each ddNTP (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, ddTTP)—to ensure base-specific termination: in the ddATP reaction, for example, chains terminate only at positions where adenine is incorporated. This setup yields fragments starting from one base beyond the primer and extending up to approximately 500–1000 bases, depending on polymerase efficiency and reaction conditions, forming a complete "ladder" for each base type when separated by size.[15] The distribution of fragment lengths arises from the probabilistic nature of ddNTP incorporation, resulting in an exponential decrease in termination likelihood at successive positions along the template. The probability of termination at position (where position 1 is the first base after the primer) is modeled aswith representing the ddNTP-to-dNTP ratio for the specific base, approximating a geometric distribution under low conditions. This ensures roughly equal representation of fragments across the sequence length, as longer chains are less likely to form due to cumulative non-termination events, providing the resolution needed to read the sequence from shortest to longest fragment.

Role of Dideoxynucleotides

Dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) are 2',3'-dideoxynucleoside 5'-triphosphates, which differ from standard deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs) by lacking a hydroxyl group at the 3' position of the deoxyribose sugar.[16] This structural modification prevents the formation of a phosphodiester bond between the 3' carbon of the newly incorporated nucleotide and the 5' phosphate of the incoming nucleotide, thereby terminating DNA chain extension.[16] ddNTPs are typically synthesized chemically from nucleosides through multi-step processes involving protection, phosphorylation, and deoxygenation, or enzymatically using nucleotide kinases and pyrophosphorylases on modified nucleosides; alternative methods include periodate oxidation of ribonucleoside triphosphates followed by reduction to remove the 2' and 3' hydroxyl groups.[17] In Sanger sequencing, DNA polymerases such as Sequenase (a modified T7 DNA polymerase) or Taq polymerase incorporate ddNTPs into the growing DNA strand opposite their complementary template base with kinetic efficiency comparable to dNTPs, as the absence of the 3'-OH does not significantly impair initial base pairing or phosphodiester bond formation with the previous nucleotide.[18] Once incorporated, however, the lack of a 3'-OH group halts further elongation, producing a nested set of DNA fragments terminated at each position where the complementary base occurs.[16] This selective termination relies on the probabilistic incorporation of ddNTPs amid a vast excess of dNTPs. Historically, early chain-terminating inhibitors in DNA sequencing drew from analogs like cordycepin (3'-deoxyadenosine), a natural nucleoside antibiotic, which inspired the development of ddNTPs as more effective, base-specific terminators; the 1977 method by Sanger et al. formalized the use of all four ddNTPs (ddATP, ddCTP, ddGTP, ddTTP).[16] In modern applications, fluorescently labeled ddNTPs, such as those in BigDye Terminator kits from Applied Biosystems, feature distinct fluorophores attached to each ddNTP (e.g., FAM for ddGTP, JOE for ddTTP, TAMRA for ddCTP, ROX for ddATP), enabling single-reaction sequencing with multicolored detection.[19] The ratio of ddNTPs to dNTPs is optimized to approximately 1:100 (1% ddNTP) to generate a balanced distribution of fragment lengths, ensuring sufficient short fragments for sequence resolution while allowing extension up to 500–1000 bases without excessive over-termination.[20] Imbalances in this ratio can skew results: an excess of ddNTPs leads to predominantly short fragments and poor coverage of longer sequences, whereas insufficient ddNTPs results in fewer terminations overall, yielding weak signals for shorter fragments and incomplete ladders.[20] To address challenges like band compressions in gel electrophoresis caused by stable secondary structures in GC-rich regions, analogs such as 7-deaza-dGTP are substituted for dGTP (or a portion thereof) in sequencing reactions; the 7-deaza modification disrupts guanine's ability to form Hoogsteen base pairs, reducing compression artifacts and improving readability without altering termination kinetics significantly.[21] This improvement is particularly valuable for sequencing templates with high GC content, where standard ddGTP incorporation can lead to overlapping bands.[21]Classical Sanger Sequencing Procedure

Primer Annealing and Extension

In the classical Sanger sequencing procedure, template preparation begins with obtaining single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) to serve as the substrate for primer annealing and extension. Early implementations utilized M13 bacteriophage vectors, which naturally produce ssDNA upon infection of host cells, providing a convenient source for sequencing inserts up to several hundred base pairs.[16] For double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) templates, such as plasmids or PCR products, denaturation is required to separate the strands; this is typically achieved through alkali treatment (e.g., with sodium hydroxide) or heat (boiling at 100°C for 5-10 minutes) to yield ssDNA without damaging the nucleic acid backbone.[22] Primer design involves selecting or synthesizing a short oligonucleotide complementary to a known sequence adjacent to the 3' end of the target region on the template strand, ensuring specificity for initiation of DNA synthesis. In the original method, primers were derived from restriction enzyme fragments of known sequence, but by the early 1980s, synthetic oligonucleotides of 15-20 bases became standard, allowing flexibility for any template with a characterized flanking region.[16][23] Annealing occurs by mixing the primer (typically 1-5 pmol) with the denatured template (0.1-1 μg) in a buffered solution containing salts like Tris-HCl and MgCl₂, followed by incubation at 37-50°C for 10-30 minutes to promote specific hybridization while minimizing non-specific binding.[15] The extension reaction follows annealing and employs DNA polymerase to synthesize complementary strands from the primer, incorporating deoxynucleotides (dNTPs) and chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) in a ratio that generates fragments of varying lengths. The Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I, lacking 5'-3' exonuclease activity, was used in the original protocol at 0.1-0.5 units per reaction, with incubation at 37°C for 30-60 minutes in a total volume of 10-20 μL; labeling for detection occurs via incorporation of radiolabeled α-³²P-dATP during synthesis.[16] Later refinements in the classical method adopted Sequenase (a modified T7 DNA polymerase) for improved processivity and speed, maintaining similar conditions but enabling longer reads up to 500 bases. Unlike modern cycle sequencing, this step involves linear amplification without thermal cycling, producing a population of terminated fragments in a single round of extension. Common challenges during annealing and extension include template secondary structures, particularly in GC-rich regions, which can impede polymerase progression and cause incomplete synthesis. These are often resolved by increasing the annealing or extension temperature (up to 50-55°C) to disrupt hairpins or adding 5-10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to the reaction mix, which lowers the melting temperature of structured regions without compromising enzyme activity.[24][25]Gel Electrophoresis and Detection

In classical Sanger sequencing, the DNA fragments generated from the four separate chain-termination reactions (for adenine, cytosine, guanine, and thymine) are separated based on size using denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The gel is typically prepared as a 4-20% polyacrylamide matrix with an acrylamide to bis-acrylamide ratio of 19:1, incorporating 7 M urea as a denaturant to unfold secondary structures and ensure linear migration of single-stranded DNA.[26][27] The gel is cast between glass plates to a uniform thickness of 0.4 mm, which provides high resolution for distinguishing fragments differing by a single nucleotide.[27] The reaction products are denatured by heating in formamide-containing loading dye and loaded into four adjacent lanes of the gel, one for each termination reaction. Electrophoresis is conducted in 1× TBE buffer under constant power of 30-60 W, typically reaching 1-2 kV, which drives the negatively charged DNA fragments toward the anode.[26][28] Separation occurs by molecular size, with fragments differing by one base pair migrating approximately 1 cm further per hour under these conditions, allowing bands to resolve over the length of a 30-50 cm gel.[28] This size-based fractionation positions shorter fragments (corresponding to earlier terminations) closer to the bottom of the gel. Detection of the radiolabeled fragments (usually with ³²P or ³⁵S) relies on autoradiography, where the dried gel is exposed to X-ray film for 12-48 hours to capture the emitted radiation as dark bands indicating termination positions. In the 1990s, phosphorimaging systems replaced traditional film for faster, more quantitative detection by scanning storage phosphor screens exposed to the gel, reducing processing time to hours while enabling digital analysis.[29] This approach yields readable sequences of up to 500-800 bases, though resolution diminishes for longer fragments due to band broadening.[30] Challenges such as band compressions, where GC-rich regions form stable secondary structures that migrate anomalously, can obscure sequence reading; these are often resolved by substituting dGTP with dITP (deoxyinosine triphosphate) in the extension reaction to weaken base pairing. Due to the radioactive labels employed, all procedures demand strict safety measures, including lead shielding, dosimeter monitoring, glove use, and regulated disposal of radioactive waste to minimize exposure risks.Sequence Reading and Assembly

In classical Sanger sequencing, sequence reading begins with the manual interpretation of the autoradiograph from polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, where four parallel lanes display radiolabeled DNA fragments terminated by each dideoxynucleotide (ddATP, ddCTP, ddGTP, or ddTTP). The operator visually aligns bands across the lanes from bottom (shortest fragments) to top (longest), assigning the base corresponding to the lane containing the band at each successive position, typically yielding reads of 200–500 base pairs in early implementations.[15][31] Ambiguities in band positions, such as compressions in GC-rich regions where secondary structures cause fragments to migrate anomalously and overlap, are resolved through visual inspection and, if necessary, re-running the sequencing reaction under modified conditions, including substitution of dITP for dGTP or addition of DMSO to disrupt secondary structures.[32][33] This process demands skilled technicians to distinguish true signals from noise, often requiring multiple gels per template for confirmation.[9] Early semi-automated analysis emerged with the Staden package, developed in the late 1970s and refined through the 1980s, which digitized gel autoradiographs using a graphics tablet to input band positions and intensities for base-calling via lane alignment algorithms.[34] The package's components, such as DBGel for data entry and analysis tools for peak-like band intensity processing, reduced subjective errors in base assignment compared to pure manual methods.[35] Sequence assembly involves aligning overlapping reads—typically 200–500 bp long—after trimming vector or primer sequences, using overlap detection to build contiguous sequences (contigs) with programs like the Staden package's GAP module, which iteratively merges fragments based on sequence similarity thresholds.[36] This shotgun-style approach achieves an overall error rate of approximately 0.001% per base in well-resolved assemblies, though manual verification is essential to correct mismatches.[37][35] Despite these advances, classical sequence reading and assembly remained labor-intensive, often requiring hours per gel for manual or semi-automated processing, limiting throughput to a few kilobases per day; computational tools like Staden reduced this to minutes per read, facilitating genome-scale efforts.[38][39]Modern Dye-Terminator Sequencing

Fluorescent ddNTP Incorporation

In modern dye-terminator Sanger sequencing, fluorescent labels are incorporated directly into the chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) rather than the primers, enabling a single-tube reaction for all four bases. Each ddNTP (ddATP, ddCTP, ddGTP, ddTTP) is conjugated with a spectrally distinct fluorophore attached via a linker to the base of the nucleotide, which does not interfere with base pairing or polymerase recognition during extension. This chemistry was pioneered using four chemically tuned fluorescent dyes—two fluorescein derivatives and two rhodamine derivatives—optimized for distinct excitation and emission spectra to allow simultaneous detection.[13] Common implementations, such as those in commercial kits, employ dyes providing emission peaks at approximately 520 nm (green), 548 nm (yellow), 581 nm (orange), and 605 nm (red), respectively.[40] The reaction setup involves mixing all four dye-labeled ddNTPs with unlabeled deoxynucleotides (dNTPs) in a single tube containing the template DNA, primer, and DNA polymerase, eliminating the need for separate reactions per base as in classical methods. To achieve uniform fragment length distribution and compensate for varying incorporation efficiencies influenced by the bulky dye moieties—particularly lower efficiency for dye-ddGTP—the molar ratios of dye-ddNTP to dNTP are adjusted, typically around 1:100 overall but higher (e.g., 1:50) for ddGTP relative to its complementary dGTP. Modified polymerases, such as Thermo Sequenase (a thermostable variant of T7 DNA polymerase with mutations enhancing ddNTP fidelity), are employed to improve balanced incorporation of the dye-terminators, reducing bias and extending readable sequence lengths up to 800-1000 bases.[41][42] Following the extension reaction, unincorporated dye-ddNTPs must be removed to prevent interference with downstream detection, as residual free dyes can cause spectral noise. Common cleanup methods include ethanol precipitation, where sodium acetate and cold ethanol are added to selectively precipitate the extended DNA fragments while soluble dyes remain in the supernatant, or silica-based spin columns that bind DNA under chaotropic conditions and elute it free of small-molecule contaminants. These techniques recover over 90% of fragments longer than 20 bases, ensuring clean samples for electrophoresis.[43] This fluorescent ddNTP approach offers key advantages over earlier radioactive or dye-primer methods, including elimination of lane-to-lane alignment artifacts from multi-gel runs and simplified workflow through single-reaction multiplexing, supporting high-throughput processing of up to 96 samples simultaneously in automated systems. By incorporating the label at the terminus, it also minimizes signal quenching from dye-dye interactions during fragment separation.[13]Cycle Sequencing Protocol

Cycle sequencing represents an adaptation of the Sanger chain-termination method that incorporates thermal cycling to achieve linear amplification of sequencing products, enabling higher yields and compatibility with double-stranded DNA templates. Introduced in 1988, this protocol utilizes the thermostable DNA polymerase from Thermus aquaticus (Taq) or engineered variants, which withstand repeated heating without denaturation, allowing for 25-30 cycles of denaturation at 95-96°C for 10-30 seconds, primer annealing at 50°C for 5-10 seconds, and extension at 60°C for 1-4 minutes. This cycling process generates a population of fluorescently labeled DNA fragments terminated by dye-labeled dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs), with each cycle linearly increasing the amount of product through repeated primer extension on the template strand.[44] The protocol accommodates various template types, including double-stranded PCR amplicons, plasmids, and cosmids up to several kilobases, eliminating the need for single-stranded DNA preparation via cloning as required in classical methods. A typical 10-20 µL reaction mix includes 20-50 ng of template DNA, 3.2 pmol of sequencing primer, and 8 µL of premixed BigDye Terminator v3.1 Ready Reaction Mix (from Applied Biosystems, now Thermo Fisher Scientific), which contains 200 µM each dNTP, approximately 1 µM fluorescent ddNTPs, Taq polymerase, and buffer components.[44] The BigDye Terminator v3.1 kit serves as the industry standard for this chemistry, incorporating improved dye terminators that minimize secondary structure formation and reduce artifactual peaks in electropherograms compared to earlier versions. By performing linear amplification over multiple cycles, the protocol enhances product yield 10- to 100-fold relative to single-round linear extension, improving signal strength for detection while maintaining the random termination distribution essential for sequence resolution. Optimization strategies include adding 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to the reaction mix for GC-rich templates (>60% GC content), which disrupts secondary structures and promotes more uniform extension.[45] Additionally, limiting cycles to 25-30 prevents signal degradation from excessive heating, which can lead to template depurination or incomplete extensions in longer reads.[46]Capillary Electrophoresis Automation

Capillary electrophoresis automation revolutionized Sanger sequencing by replacing labor-intensive slab gel methods with high-throughput, instrument-based separation of fluorescently labeled DNA fragments. Commercial systems, such as the Applied Biosystems (ABI) 3730xl DNA Analyzer, utilize 96-capillary arrays to process up to 96 samples simultaneously, enabling efficient analysis of cycle sequencing products. These arrays consist of polymer-filled capillaries with an inner diameter of 50 µm and a length of 36 cm, optimized for achieving read lengths of 600-900 bases with high accuracy (98.5% up to 700 bases).[47][48] The capillaries are filled with a replaceable polymer matrix, such as POP-7, which provides the sieving medium for size-based separation of termination products differing by single nucleotides.[49] The process begins with electrokinetic injection, where a high-voltage pulse (typically 1-2 kV for 5-30 seconds) draws the negatively charged DNA fragments into the capillaries from the sample wells. Separation then occurs under an applied voltage of 8-15 kV, driving the fragments through the polymer matrix toward the positive electrode at speeds inversely proportional to their size, with shorter fragments migrating faster. Detection is achieved via laser-induced fluorescence at the distal end of the capillaries, using a 488 nm argon-ion laser for excitation and four distinct emission filters to distinguish the fluorescent dyes attached to the dideoxynucleotides. This four-color detection allows real-time monitoring of fragment elution as colored peaks in a chromatogram.[50] Base-calling is performed automatically using software like the KB BaseCaller, which applies mobility-corrected peak detection algorithms to account for slight variations in fragment migration due to sequence context or polymer conditions, thereby improving accuracy over earlier phred-based methods. The output consists of .ab1 files containing raw trace data, quality scores, and called base sequences, facilitating downstream analysis and assembly.[51][52] These systems deliver high throughput, generating 1000-2000 sequence reads per day per instrument, depending on run configuration and template quality, making them suitable for large-scale projects like genome finishing. Maintenance involves periodic polymer refills every 24 hours to ensure consistent performance, as a 96-capillary run consumes 200-250 µL of polymer, and capillary arrays have a lifetime of 100-300 runs before replacement to avoid degradation in separation efficiency.[53][54][47]Microfluidic Sanger Sequencing

Device Design and Fabrication

Microfluidic devices for Sanger sequencing are typically fabricated using biocompatible materials such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) or glass to ensure compatibility with biochemical reactions and optical detection. PDMS is favored for its flexibility, optical transparency, and ease of prototyping via soft lithography, which involves creating a master mold using photolithography with photoresist (e.g., SU-8) on a silicon wafer, followed by pouring and curing uncured PDMS elastomer, and sealing the replica to a glass substrate via plasma oxidation bonding. Glass substrates, often borosilicate wafers, are employed for their superior thermal conductivity, chemical inertness, and low autofluorescence, with fabrication achieved through photolithography to define patterns, wet chemical etching (e.g., HF-based) to form channels, and anodic bonding to seal layers under high voltage and temperature. These methods enable precise control over microscale features while minimizing contamination risks in integrated sequencing workflows.[55] Channel designs in these devices consist of interconnected networks supporting parallel processing, typically featuring 4 to 96 serpentine or straight channels with widths of 10–100 µm and depths of 10–50 µm to facilitate efficient electrokinetic flow and separation of DNA fragments by size. Integrated reservoirs at channel inlets and outlets accommodate reagents like primers, dNTPs, and ddNTPs, while embedded platinum or gold electrodes enable electroosmotic pumping and electrophoretic injection without external pumps. These designs prioritize miniaturization to enhance heat dissipation during thermal cycling and reduce diffusion times for mixing.[56] Advanced integration includes on-chip PCR amplification chambers (e.g., 300–500 µm wide reaction zones with resistive heaters), passive mixing structures like herringbone patterns for reagent blending, and transparent detection windows aligned for laser-induced fluorescence readout of dye-labeled terminators. Complete devices are compact, often measuring 5 cm × 7 cm, allowing stacking or arraying for higher throughput while maintaining portability. Such features adapt the Sanger chemistry to confined spaces by minimizing dead volumes and enabling automated fluid handling. Miniaturization via microfluidics scales reagent consumption down to nanoliter volumes (e.g., 100 nL per sequencing reaction) compared to microliter scales in traditional capillary systems, reducing costs and waste by orders of magnitude. Parallelization extends to 384 channels in optimized designs, boosting throughput for targeted re-sequencing without compromising read lengths. Early commercial examples include the Caliper LifeSciences LabChip systems from the 2000s for genetic analysis platforms.Adapted Sequencing Chemistry

To adapt Sanger sequencing chemistry for microfluidic environments, enzymes are optimized to enhance performance in confined spaces with limited reagent volumes and rapid thermal cycling. Hot-start polymerases, such as modified Taq variants, are employed to inhibit non-specific primer extension at ambient temperatures, reducing artifacts in nanoliter-scale reactions and improving specificity during initial denaturation steps.[57] These enzymes activate only upon heating, which is critical in integrated chips where premature activity could lead to low yields. While phi29 DNA polymerase, known for its high processivity in amplification tasks, has been explored for extended read lengths in some isothermal adaptations, its strand-displacing activity is less common in standard thermal-cycled Sanger protocols on chips due to compatibility issues with ddNTP termination.[58] Buffer compositions are adjusted to facilitate faster electroosmotic flow and minimize operational issues in microchannels. Low-viscosity sieving matrices, such as linear polyacrylamide (LPA) or poly(N,N-dimethylacrylamide) (pDMA), replace higher-viscosity gels used in traditional setups, enabling high-resolution separation of DNA fragments up to 600 bases while reducing pressure requirements for matrix loading.[59] Buffers are typically maintained at pH 8.0-9.0 using Tris-borate-EDTA systems to optimize polymerase activity and suppress bubble formation from electrolysis, which can disrupt electrokinetic flow in short channels.[60] Dye-labeling and ddNTP incorporation are refined for enhanced signal detection and uniform fragment distribution in compact detection volumes. Energy-transfer dyes, such as fluorescein-rhodamine cassettes, are integrated into ddNTP terminators to boost fluorescence intensity via Förster resonance energy transfer, improving signal-to-noise ratios in short optical path lengths typical of microfluidic setups.[61] To promote longer reads and even peak heights, ddNTP:dNTP ratios are lowered to approximately 0.5:100, shifting the fragment length distribution toward higher molecular weights without compromising termination efficiency.[62] On-chip reactions leverage microfluidic principles for efficient reagent handling and temperature management. Electrokinetic mixing combines template, primer, polymerase, and dNTP/ddNTP mixtures through voltage-controlled flows, achieving homogeneous reactions in volumes as low as 100 nL without mechanical pumps.[63] Thermal control is provided by integrated Peltier elements, enabling rapid cycling (denaturation at 96°C, annealing at 50°C, extension at 60°C) with cycle times under 5 minutes for 25-30 iterations, accelerating the overall process to under 2 hours compared to bulk methods.[64] Key challenges in microfluidic adaptation include biomolecule adsorption to channel surfaces, which is mitigated by polyethylene glycol (PEG) coatings, such as PLL-g-PEG layers that create a hydrophilic barrier and reduce DNA loss by up to 90%.[65] These modifications yield sequencing read lengths and accuracies comparable to capillary electrophoresis systems, typically supporting up to 500-600 bases with >99% accuracy in optimized devices.[66]Integrated Platforms and Commercial Systems

The Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, introduced in 1999, represents an early commercial platform for microfluidic analysis in Sanger sequencing workflows, utilizing chip-based capillary electrophoresis to perform fragment analysis and quality control on up to 12 samples per chip.[67] This system enables parallel processing of 10-100 samples across multiple chips in a single run, streamlining post-sequencing detection by automating sizing and quantification of dye-labeled fragments with minimal reagent volumes.[68] Its integration of microfluidics reduced manual handling compared to slab gel methods, though it primarily supports electrophoresis rather than full cycle sequencing.[69] Research prototypes advanced integrated microfluidic Sanger sequencing in the early 2000s, with the Barron group at Stanford University demonstrating miniaturized electrophoresis systems using glass-PDMS hybrid chips for DNA sequencing and genotyping.[70] These 96-channel devices achieved read lengths of up to 500 base pairs by optimizing polymer solutions for separation efficiency, enabling potential throughputs of up to 10,000 reads per day in high-density arrays.[70] Similarly, the Mathies group developed hybrid glass-PDMS microdevices for nanoliter-scale Sanger sequencing, integrating thermal cycling, purification, and electrophoresis to produce high-quality sequences with reduced sample volumes.[61] Commercial systems evolved with the IntegenX Apollo 100, launched in 2010, a fully automated robotic platform employing microfluidic solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) for Sanger cycle sequencing preparation and cleanup.[71] Capable of processing 96 samples in under 3 hours, it generates sequences comparable to manual methods while minimizing contamination and labor.[71] The subsequent RapidHIT system from IntegenX, introduced in 2012, provides fully integrated microfluidic processing for forensic DNA analysis, completing sample-to-profile workflows in 5-7 minutes per sample using adapted capillary electrophoresis.[72] These platforms leverage adapted sequencing chemistry for point-of-use applications, though broader adoption remains limited due to next-generation sequencing dominance. As of 2025, commercial developments in microfluidic Sanger sequencing have been limited, with continued niche applications in forensics and point-of-care diagnostics. Microfluidic integration in these systems significantly lowers costs, with reagent consumption reduced by up to 1,000-fold compared to traditional capillary methods.[61] Hands-on time is also minimized to less than 1 hour for multi-sample runs, enhancing efficiency in targeted re-sequencing and validation tasks.[71]Applications

Genomic Sequencing Projects

Sanger sequencing was the cornerstone of the Human Genome Project (HGP), an international effort spanning 1990 to 2003 that aimed to determine the sequence of the human genome. Approximately 90% of the genome was sequenced using Sanger methods, producing around 30 million reads with an average length of about 770 base pairs, achieving roughly 8x coverage. The project adopted a hierarchical shotgun sequencing strategy, in which large genomic fragments were cloned into bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) vectors to generate a physical map of overlapping clones, followed by random shotgun fragmentation and Sanger sequencing of those clones to assemble the sequence. This approach ensured high accuracy and enabled the draft sequence release in 2001, with finishing efforts completing over 99% of the euchromatic regions by 2003. Sanger sequencing similarly powered several landmark eukaryotic genome projects in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) genome, the first complete eukaryotic genome, was sequenced in 1996 across 12 million base pairs using collaborative Sanger efforts coordinated by the international yeast community. In 2000, the Drosophila melanogaster fruit fly genome of approximately 180 million base pairs was assembled via a whole-genome shotgun approach reliant on Sanger reads, providing insights into gene regulation and development. The Mus musculus (mouse) genome followed in 2002, encompassing 2.5 billion base pairs with 7-8x average coverage from Sanger data, facilitating comparative genomics with humans. These projects typically employed 8-10x coverage to balance redundancy and cost while minimizing errors in assembly. Beyond initial sequencing, Sanger methods were critical for finishing strategies in large-scale projects, addressing gaps left by initial shotgun phases through targeted re-sequencing for closure and polymorphism detection. Paired-end reads, generated from plasmid or BAC clone libraries, were instrumental in scaffolding contigs by providing linking information across repetitive or unresolved regions, enhancing overall assembly contiguity. Automated capillary electrophoresis further accelerated these finishing tasks by enabling high-throughput processing of Sanger reactions. In the post-NGS era, Sanger sequencing has been integrated into hybrid workflows to validate and refine NGS-based assemblies, particularly for error-prone regions. For instance, in the 1000 Genomes Project during the 2010s, Sanger was employed to confirm NGS-detected variants, contributing to high-confidence calls in challenging genomic loci and resolving ambiguities in up to several percent of variant sites. Data from these Sanger efforts were output as FASTA files with associated Phred quality scores, assembled into contigs using software like Phrap, which incorporated base-quality information to produce reliable consensus sequences.Targeted Re-Sequencing and Validation

Targeted re-sequencing using Sanger sequencing typically involves the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of specific genomic regions, such as exons, ranging from 300 to 500 base pairs, followed by sequencing to detect variants with high precision.[9][73] This amplicon-based approach allows focused interrogation of predefined targets, making it ideal for low-throughput analysis where accuracy is paramount over speed.[74] Sanger sequencing is widely regarded as the gold standard for validating single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) due to its error rate below 0.001% and ability to resolve base calls unambiguously.[75][76] In next-generation sequencing (NGS) workflows, Sanger sequencing is routinely employed to confirm putative variants, with studies reporting validation rates exceeding 99% for high-quality NGS calls.[77] For instance, in cancer genomics initiatives like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, initiated in 2006 and ongoing), Sanger sequencing has been used to verify somatic mutations identified through NGS, ensuring reliability in downstream analyses.[78] This confirmatory step is particularly valuable for novel or low-frequency variants, where NGS may introduce artifacts, and has contributed to the project's characterization of over 11,000 tumors across 33 cancer types. Mutation detection via Sanger sequencing relies on electropherogram analysis, where heterozygous variants in diploid samples are identified by comparable peak heights of the two bases, typically in a 50:50 ratio, allowing distinction from homozygous calls or noise.[79][80] The method exhibits sensitivity greater than 99% for insertions and deletions (indels) smaller than 20 base pairs when bidirectional sequencing is performed with high-quality traces (Phred score >20).[81] This high fidelity enables reliable calling of heterozygous indels, which appear as overlapping or shifted peaks, outperforming NGS in resolution for such small structural changes.[82] For longer targets exceeding standard read lengths, workflows incorporate primer walking, where initial sequencing results guide the design of subsequent primers to iteratively extend coverage across the region.[83] Variant detection is further automated using software such as Mutation Surveyor, which analyzes trace files to identify mutations, quantify allele ratios, and flag low-frequency variants with over 99% accuracy in heterozygous indel detection.[84][85] Prominent applications include BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene screening for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer risk, where Sanger sequencing has been the primary method since the 1990s, enabling comprehensive exon analysis and mutation confirmation in clinical cohorts.[86][87] Additionally, Sanger sequencing facilitates error correction in de novo genome assemblies by validating and refining ambiguous regions from NGS data, improving contiguity and base accuracy in hybrid approaches.[88][89]Clinical and Forensic Uses

Sanger sequencing has played a pivotal role in clinical diagnostics, particularly in human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing for organ and tissue transplantation since the early 1990s, when sequencing-based typing (SSBT) methods were introduced to achieve higher resolution allele identification compared to serological techniques.[90] This approach sequences specific exons, such as 2 and 3, to match donors and recipients, reducing rejection risks in procedures like kidney and bone marrow transplants.[91] In infectious disease management, Sanger sequencing remains the gold standard for HIV-1 drug resistance genotyping, targeting regions like the protease gene to detect mutations conferring resistance to antiretroviral therapies, typically yielding reads of around 300 base pairs.[92] Commercial kits amplify and sequence the protease and reverse transcriptase genes, enabling clinicians to tailor regimens for patients failing therapy.[93] For inherited disorders, Sanger sequencing is employed in genetic testing of the CFTR gene to identify mutations causing cystic fibrosis, confirming diagnoses and carrier status through targeted sequencing of exons and splice sites.[94] Laboratories certified under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) perform these assays with rigorous quality controls, ensuring analytical validity for clinical decision-making.[95] In forensic applications, Sanger sequencing supports short tandem repeat (STR) profiling by providing detailed sequence characterization of CODIS loci, aiding in mixture deconvolution or variant allele resolution beyond standard length-based methods.[96] It is particularly valuable for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) analysis in degraded or trace samples, such as old bones or hair, where sequencing the control region yields read lengths exceeding 800 base pairs to establish maternal lineage or identify remains when nuclear DNA is insufficient.[97] Regulatory frameworks underscore Sanger sequencing's reliability in clinical settings; for instance, it has been integral to FDA-approved companion diagnostic tests, including those for KRAS mutations in colorectal cancer since 2009, where sequencing detects exon 2 alterations to guide anti-EGFR therapy eligibility.[98] CLIA certification mandates proficiency testing, personnel qualifications, and validation for labs offering Sanger-based assays, ensuring reproducible results in diagnostic workflows.[99] More recently, from 2020 to 2025, Sanger sequencing has been adapted for SARS-CoV-2 surveillance, focusing on the spike protein gene to detect variants like Omicron through targeted amplification and sequencing of key mutation hotspots, facilitating rapid variant tracking in clinical and public health responses.[14] While traditional Sanger setups are lab-bound, emerging field-deployable adaptations, often integrated with portable PCR, have enabled on-site sequencing in remote labs during outbreaks.[100]Limitations and Comparisons

Technical Challenges and Error Sources

Sanger sequencing encounters several inherent error sources that can compromise the accuracy and reliability of base calls. One primary challenge is polymerase misincorporation during the chain-termination reaction, where the DNA polymerase incorrectly incorporates a nucleotide, leading to substitution errors at a rate of approximately 1 in 10,000 bases for commonly used enzymes like Taq polymerase.[101] Additionally, dye-labeled terminators can induce mobility shifts during capillary electrophoresis, resulting in misaligned peaks that manifest as +1 or -1 base call errors due to differential migration of dye-DNA complexes.[102] Band compressions further exacerbate issues, particularly in regions forming stable hairpin structures, where the single-stranded DNA folds back on itself, causing overlapping peaks and ambiguous resolutions on the electropherogram.[21] Read length limitations represent another technical hurdle, with signal intensity typically decaying beyond 800-1,000 bases owing to incomplete extension products and progressive loss of resolution in the sequencing reaction. This decay arises from the stochastic nature of dideoxynucleotide incorporation, which produces a heterogeneous population of fragments where longer products are underrepresented. Poly-A or poly-T runs compound this problem by inducing polymerase slippage, leading to stutter peaks or peak broadening that obscures accurate base determination in homopolymeric regions.[9] Template-related issues also contribute significantly to errors. Secondary structures in the DNA template, such as GC-rich hairpins or guanine stretches, can stall the polymerase, halting extension and producing abrupt stops or weak signals downstream; these are often mitigated by additives like betaine, which equalizes base-pairing stability and reduces structure formation.[103] In heterozygous samples, peak height imbalances exceeding a 70:30 ratio (major to minor allele) become challenging to resolve, as the weaker signal may be indistinguishable from noise, limiting reliable detection to variants with more balanced representation.[104] Quantitatively, Sanger sequencing achieves a typical Phred quality score of Q20, corresponding to 99% base call accuracy, across most reads under optimal conditions. However, quality deteriorates markedly in problematic regions like homopolymers, where scores can drop to Q10 (90% accuracy) due to overlapping peaks and reduced peak separation. Consequently, approximately 5-10% of reads necessitate manual review to confirm ambiguous calls, particularly in low-quality tails or complex motifs. Recent advancements in the 2020s, such as machine learning-based base-calling algorithms, have addressed some of these limitations by improving peak deconvolution and reducing error rates by up to 20% in challenging sequences.[105][106]Throughput and Cost Comparisons to NGS

Sanger sequencing exhibits significantly lower throughput compared to next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. A typical capillary electrophoresis-based Sanger sequencer, such as the ABI 3730xl with 96 capillaries, can generate approximately 2 megabases (Mb) of sequence data per day, assuming read lengths of 700–1,000 base pairs (bp) and multiple runs over 24 hours.[107] In contrast, high-throughput NGS platforms like Illumina's NovaSeq X series achieve outputs exceeding 100 gigabases (Gb) per day, representing over 50,000-fold higher throughput for large-scale projects. This disparity arises from Sanger's serial processing of individual DNA fragments versus NGS's massively parallel analysis of millions of fragments simultaneously.[108] Cost comparisons further highlight NGS's advantages for genome-scale sequencing. Sanger sequencing incurs costs of approximately $0.50–$2 per read, translating to $500–$1,000 per finished megabase when accounting for assembly and finishing steps in low- to medium-throughput settings.[109] NGS, however, has reduced costs to approximately $50–$200 per gigabase as of 2025, making it roughly 2,500–10,000 times cheaper for sequencing large genomes like the human genome (approximately 3 Gb).[109] These economics stem from NGS's scalability, where per-base costs drop dramatically with volume, whereas Sanger remains more economical only for minimal sample numbers due to fixed reagent and labor expenses per reaction.[110] Sanger sequencing is preferred for targeted applications involving less than 10 kilobases (kb) per sample, such as variant validation or small amplicon analysis, where its high per-base accuracy (error rate <0.001%) and simplicity outweigh throughput limitations.[108] Conversely, NGS dominates de novo assembly of genomes larger than 1 megabase (Mb), enabling comprehensive genomic studies that would be impractical and cost-prohibitive with Sanger alone.[111] In hybrid workflows prevalent in 2020s large-scale projects, NGS provides bulk sequence data, with Sanger used for finishing gaps or confirming low-coverage regions to achieve reference-quality assemblies.[112]| Metric | Sanger Sequencing | NGS (e.g., Illumina) |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput (bases/day) | ~2 Mb | >100 Gb |

| Cost (per Gb) | ~$500,000 (small scale) | $50–$200 (large scale, as of 2025) |

| Input DNA | 50–100 ng per reaction | 1–10 ng per library |

| Typical read length | 700–1,000 bp | 50–300 bp (short-read) |