Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

First World

View on Wikipedia

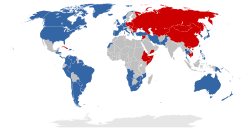

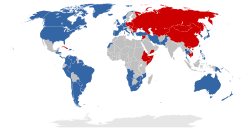

The concept of the First World was originally one of the "Three Worlds" formed by the global political landscape of the Cold War, as it grouped together those countries that were aligned with the Western Bloc of the United States. This grouping was directly opposed to the Second World, which similarly grouped together those countries that were aligned with the Eastern Bloc of the Soviet Union. However, after the Cold War ended with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the definition largely shifted to instead refer to any country with a well-functioning democratic system with little prospects of political risk, in addition to a strong rule of law, a capitalist economy with economic stability, and a relatively high mean standard of living. Various ways in which these metrics are assessed are through the examination of a country's GDP, GNP, literacy rate, life expectancy, and Human Development Index.[1][better source needed] In colloquial usage, "First World" typically refers to "the highly developed industrialized nations often considered the Westernized countries of the world".[2]

History

[edit]After World War II, the world split into two large geopolitical blocs, separating into spheres of communism and capitalism. This led to the Cold War, during which the term First World was often used because of its political, social, and economic relevance. The term itself was first introduced in the late 1940s by the United Nations.[3] Today, the terms are slightly outdated and have no official definition. However, the "First World" is generally thought of as the capitalist, industrial, wealthy, and developed countries. This definition includes the countries of North America and Western Europe, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand.[4] In contemporary society, the First World is viewed as countries that have the most advanced economies, the greatest influence, the highest standards of living, and the greatest technology.[citation needed] After the Cold War, these countries of the First World included member states of NATO, U.S.-aligned states, neutral countries that were developed and industrialized, and the former British Colonies that were considered developed.

According to Nations Online, the member countries of NATO during the Cold War included:[5]

- Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The US-aligned states included:[5]

- Israel, Japan, and South Korea.

Former British colonies included:[5]

- Australia and New Zealand.

Neutral and more or less industrialized capitalist countries included:[5]

- Austria, Ireland, Sweden, and Switzerland.

Shifting in definitions

[edit]Since the end of the Cold War, the original definition of the term "First World" is no longer necessarily applicable. There are varying definitions of the First World; however, they follow the same idea. John D. Daniels, past president of the Academy of International Business, defines the First World to be consisting of "high-income industrial countries".[6] Scholar and Professor George J. Bryjak defines the First World to be the "modern, industrial, capitalist countries of North America and Europe".[7] L. Robert Kohls, former director of training for the U.S. Information Agency and the Meridian International Center in Washington, D.C., uses First World and "fully developed" as synonyms.[8]

Other indicators

[edit]Varying definitions of the term First World and the uncertainty of the term in today's world leads to different indicators of First World status. In 1945, the United Nations used the terms first, second, third, and fourth worlds to define the relative wealth of nations (although popular use of the term fourth world did not come about until later).[9] There are some references towards culture in the definition. They were defined in terms of Gross National Product (GNP), measured in U.S. dollars, along with other socio-political factors.[9] The first world included the large industrialized, democratic (free elections, etc.) nations.[9] The second world included modern, wealthy, industrialized nations, but they were all under communist control.[9] Most of the rest of the world was deemed part of the third world, while the fourth world was considered to be those nations whose people were living on less than US$100 annually.[9] If we use the term to mean high-income industrialized economies, then the World Bank classifies countries according to their GNI or gross national income per capita. The World Bank separates countries into four categories: high-income, upper-middle-income, lower-middle-income, and low-income economies. The First World is considered to be countries with high-income economies. The high-income economies are equated to mean developed and industrialized countries.

Three-world model

[edit]

The terms "First World", "Second World", and "Third World" were originally used to divide the world's nations into three categories. The model did not emerge to its endstate all at once. The complete overthrow of the pre–World War II status quo, known as the Cold War, left two superpowers (the United States and the Soviet Union) vying for ultimate global supremacy. They created two camps, known as blocs. These blocs formed the basis of the concepts of the First and Second Worlds.[10]

Early in the Cold War era, NATO and the Warsaw Pact were created by the United States and the Soviet Union, respectively. They were also referred to as the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The circumstances of these two blocs were so different that they were essentially two worlds, however, they were not numbered first and second.[11][12][13] The onset of the Cold War is marked by Winston Churchill's famous "Iron Curtain" speech.[citation needed] In this speech, Churchill describes the division of the West and East to be so solid that it could be called an iron curtain.[citation needed]

In 1952, the French demographer Alfred Sauvy coined the term Third World in reference to the three estates in pre-revolutionary France.[14] The first two estates being the nobility and clergy and everybody else comprising the third estate.[14] He compared the capitalist world (i.e., First World) to the nobility and the communist world (i.e., Second World) to the clergy. Just as the third estate comprised everybody else, Sauvy called the Third World all the countries that were not in this Cold War division, i.e., the unaligned and uninvolved states in the "East-West Conflict".[14][15] With the coining of the term Third World directly, the first two groups came to be known as the "First World" and "Second World" respectively. Here the three-world system emerged.[13]

Post–Cold War

[edit]With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Eastern Bloc ceased to exist and with it, the perfect applicability of the term Second World.[16] The definitions of the First World, Second World, and Third World changed slightly, yet generally describe the same concepts.

Relationships with the other worlds

[edit]Historic

[edit]During the Cold War era, the relationships between the First World, Second World and the Third World were very rigid. The First World and Second World were at constant odds with one another via the tensions between their two cores, the United States and the Soviet Union, respectively. The Cold War, as its name suggests, was a primarily ideological struggle between the First and Second Worlds, or more specifically, the U.S. and the Soviet Union.[17] Multiple doctrines and plans dominated Cold War dynamics including the Truman Doctrine and Marshall Plan (from the U.S.) and the Molotov Plan (from the Soviet Union).[17][18][19] The extent of the tension between the two worlds was evident in Berlin -- which was then split into East and West. To stop citizens in East Berlin from having too much exposure to the capitalist West, the Soviet Union erected the Berlin Wall within the city.[20]

The relationship between the First World and the Third World is characterized by the very definition of the Third World. Because countries of the Third World were noncommittal and non-aligned with both the First World and the Second World, they were targets for recruitment. In the quest for expanding their sphere of influence, the United States (core of the First World) tried to establish pro-U.S. regimes in the Third World. In addition, because the Soviet Union (core of the Second World) also wanted to expand, the Third World often became a site for conflict.

Some examples include Vietnam and Korea. Success lay with the First World if at the end of the war, the country became capitalistic and democratic, and with the Second World, if the country became communist. While Vietnam as a whole was eventually communized, only the northern half of Korea remained communist.[21] The Domino Theory largely governed United States policy regarding the Third World and their rivalry with the Second World.[22] In light of the Domino Theory, the U.S. saw winning the proxy wars in the Third World as a measure of the "credibility of U.S. commitments all over the world".[citation needed]

Present

[edit]The movement of people and information largely characterizes the inter-world relationships in the present day.[23] A majority of breakthroughs and innovation originate in Western Europe and the U.S. and later their effects permeate globally. As judged by the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, most of the Top 30 Innovations of the Last 30 Years were from former First World countries (e.g., the U.S. and countries in Western Europe).[24]

The disparity between knowledge in the First World as compared to the Third World is evident in healthcare and medical advancements. Deaths from water-related illnesses have largely been eliminated in "wealthier nations", while they are still a "major concern in the developing world".[25] Widely treatable diseases in the developed countries of the First World, malaria and tuberculosis needlessly claim many lives in the developing countries of the Third World. Each year 900,000 people die from malaria and combating the disease accounts for 40% of health spending in many African countries.[26]

The International Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) announced that the first Internationalized Domain Names (IDNs) would be available in the summer of 2010. These include non-Latin domains such as Chinese, Arabic, and Russian. This is one way that the flow of information between the First and Third Worlds may become more even.[27]

The movement of information and technology from the First World to various Third World countries has created a general "aspir(ation) to First World living standards".[23] The Third World has lower living standards as compared to the First World.[13] Information about the comparatively higher living standards of the First World comes through television, commercial advertisements and foreign visitors to their countries.[23] This exposure causes two changes: a) living standards in some Third World countries rise and b) this exposure creates hopes and many from Third World countries emigrate—both legally and illegally—to these First World countries in hopes of attaining that living standard and prosperity.[23] In fact, this emigration is the "main contributor to the increasing populations of U.S. and Europe".[23] While these emigrations have greatly contributed to globalization, they have also precipitated trends like brain drain and problems with repatriation. They have also created immigration and governmental burden problems for the countries (i.e., First World) that people emigrate to.[23]

Environmental footprint

[edit]Some have argued that the most important human population problem for the world is not the high rate of population increase in certain Third World countries per se, but rather the "increase in total human impact".[23] The per-capita footprint—the resources consumed and the waste created by each person—varies globally. The highest per-person impact occurs in the First World and the lowest in the Third World: each inhabitant of the United States, Western Europe and Japan consumes 32 times as many resources and puts out 32 times as much waste as each person in the Third World.[23] However, China leads the world in total emissions, but its large population skews its per-capita statistic lower than those of more developed nations.[28][better source needed]

As large consumers of fossil fuels, First World countries drew attention to environmental pollution.[29] The Kyoto Protocol is a treaty that is based on the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which was finalized in 1992 at the Earth Summit in Rio.[30] It proposed to place the burden of protecting the climate on the United States and other First World countries.[30] Countries that were considered to be developing, such as China and India, were not required to approve the treaty because they were more concerned that restricting emissions would further restrain their development.

International relations

[edit]Until the recent past, little attention was paid to the interests of Third World countries.[31] This is because most international relations scholars have come from the industrialized, First World nations.[32] As more countries have continued to become more developed, the interests of the world have slowly started to shift.[31] However, First World nations still have many more universities, professors, journals, and conferences, which has made it very difficult for Third World countries to gain legitimacy and respect with their new ideas and methods of looking at the world.[31]

Development theory

[edit]During the Cold War, the modernization theory and development theory developed in Europe as a result of their economic, political, social, and cultural response to the management of former colonial territories.[33] European scholars and practitioners of international politics hoped to theorize ideas and then create policies based on those ideas that would cause newly independent colonies to change into politically developed sovereign nation-states.[33] However, most of the theorists were from the United States, and they were not interested in Third World countries achieving development by any model.[33] They wanted those countries to develop through liberal processes of politics, economics, and socialization; that is to say, they wanted them to follow the liberal capitalist example of a so-called "First World state".[33] Therefore, the modernization and development tradition consciously originated as a (mostly U.S.) alternative to the Marxist and neo-Marxist strategies promoted by the "Second World states" like the Soviet Union.[33] It was used to explain how developing Third World states would naturally evolve into developed First World States, and it was partially grounded in liberal economic theory and a form of Talcott Parsons' sociological theory.[33]

Globalization

[edit]The United Nations's ESCWA has written that globalization "is a widely-used term that can be defined in a number of different ways". Joyce Osland from San Jose State University wrote: "Globalization has become an increasingly controversial topic, and the growing number of protests around the world has focused more attention on the basic assumptions of globalization and its effects."[34] "Globalization is not new, though. For thousands of years, people—and, later, corporations—have been buying from and selling to each other in lands at great distances, such as through the famed Silk Road across Central Asia that connected China and Europe during the Middle Ages. Likewise, for centuries, people and corporations have invested in enterprises in other countries. In fact, many of the features of the current wave of globalization are similar to those prevailing before the outbreak of the First World War in 1914."[citation needed]

European Union

[edit]The most prominent example of globalization in the first world is the European Union (EU).[35] The European Union is an agreement in which countries voluntarily decide to build common governmental institutions to which they delegate some individual national sovereignty so that decisions can be made democratically on a higher level of common interest for Europe as a whole.[36] The result is a union of 27 Member States covering 4,233,255.3 square kilometres (1,634,469.0 sq mi) with roughly 450 million people. In total, the European Union produces almost a third of the world's gross national product and the member states speak more than 23 languages. All of the European Union countries are joined together by a hope to promote and extend peace, democracy, cooperativeness, stability, prosperity, and the rule of law.[36] In a 2007 speech, Benita Ferrero-Waldner, the European Commissioner for External Relations, said, "The future of the EU is linked to globalization...the EU has a crucial role to play in making globalization work properly...".[37] In a 2014 speech at the European Parliament, the Italian PM Matteo Renzi stated, "We are the ones who can bring civilization to globalization".[38]

Just as the concept of the First World came about as a result of World War II, so did the European Union.[36] In 1951 the beginnings of the EU were founded with the creation of European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). From the beginning of its inception, countries in the EU were judged by many standards, including economic ones. This is where the relation between globalization, the EU, and First World countries arises.[35] Especially during the 1990s when the EU focused on economic policies such as the creation and circulation of the Euro, the creation of the European Monetary Institute, and the opening of the European Central Bank.[36]

In 1993, at the Copenhagen European Council, the European Union took a decisive step towards expanding the EU, what they called the Fifth Enlargement, agreeing that "the associated countries in Central and Eastern Europe that so desire shall become members of the European Union". Thus, enlargement was no longer a question of if, but when and how. The European Council stated that accession could occur when the prospective country is able to assume the obligations of membership, that is that all the economic and political conditions required are attained. Furthermore, it defined the membership criteria, which are regarded as the Copenhagen criteria, as follows:[39]

- stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities

- the existence of a functioning market economy as well as the capacity to cope with competitive pressure and market forces within the Union

- the ability to take on the obligations of membership including adherence to the aims of political, economic and monetary union

It is clear that all these criteria are characteristics of developed countries. Therefore, there is a direct link between globalization, developed nations, and the European Union.[35]

Multinational corporations

[edit]A majority of multinational corporations find their origins in First World countries. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, multinational corporations proliferated as more countries focused on global trade.[40] The series of General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and later the World Trade Organization (WTO) essentially ended the protectionist measures that were dissuading global trade.[40] The eradication of these protectionist measures, while creating avenues for economic interconnection, mostly benefited developed countries, who by using their power at GATT summits, forced developing and underdeveloped countries to open their economies to Western goods.[41]

As the world starts to globalize, it is accompanied by criticism of the current forms of globalization, which are feared to be overly corporate-led. As corporations become larger and multinational, their influence and interests go further accordingly. Being able to influence and own most media companies, it is hard to be able to publicly debate the notions and ideals that corporations pursue. Some choices that corporations take to make profits can affect people all over the world. Sometimes fatally.[citation needed]

The third industrial revolution is spreading from the developed world to some, but not all, parts of the developing world. To participate in this new global economy, developing countries must be seen as attractive offshore production bases for multinational corporations. To be such bases, developing countries must provide relatively well-educated workforces, good infrastructure (electricity, telecommunications, transportation), political stability, and a willingness to play by market rules.[42]

If these conditions are in place, multinational corporations will transfer via their offshore subsidiaries or to their offshore suppliers, the specific production technologies and market linkages necessary to participate in the global economy. By themselves, developing countries, even if well-educated, cannot produce at the quality levels demanded in high-value-added industries and cannot market what they produce even in low-value-added industries such as textiles or shoes. Put bluntly, multinational companies possess a variety of factors that developing countries must have if they are to participate in the global economy.[42]

Outsourcing

[edit]Outsourcing, according to Grossman and Helpman, refers to the process of "subcontracting an ever expanding set of activities, ranging from product design to assembly, from research and development to marketing, distribution and after-sales service".[43][better source needed] Many companies have moved to outsourcing services in which they no longer specifically need or have the capability of handling themselves.[44] This is due to considerations of what the companies can have more control over.[44] Whatever companies tend to not have much control over or need to have control over will outsource activities to firms that they consider "less competing".[44] According to SourcingMag.com, the process of outsourcing can take the following four phases.[45]

- strategic thinking

- evaluation and selection

- contract development

- outsourcing management

Outsourcing is among some of the many reasons for increased competition within developing countries.[46][better source needed] Aside from being a reason for competition, many First World countries see outsourcing, in particular offshore outsourcing, as an opportunity for increased income.[47] As a consequence, the skill level of production in foreign countries handling the outsourced services increases within the economy; and the skill level within the domestic developing countries can decrease.[48] It is because of competition (including outsourcing) that Robert Feenstra and Gordon Hanson predict that there will be a rise of 15–33 percent in inequality amongst these countries.[46][better source needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ First World, Investopedia

- ^ "First world". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Macdonald, Theodore (2005). Third World Health: Hostage to First World Health. Radcliffe Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 1-85775-769-6. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "First, Second and Third World". Nations Online. July 24, 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Countries of the First World". Nations Online.

- ^ Daniels, John (2007). International business: environments and operations. Prentice Hall. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-13-186942-4.

- ^ Bryjak, George (1997). Sociology: cultural diversity in a changing world. Allyn & Bacon. p. 8. ISBN 0-205-26435-2.

- ^ Kohls, L. (2001). Survival kit for overseas living: for Americans planning to live and work abroad. Nicholas Brealey Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 1-85788-292-X.

- ^ a b c d e Macdonald, Theodore (2005). Third World Health: Hostage to First World Health. Radcliffe Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 1-85775-769-6.

- ^ Gaddis, John (1998). We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-19-878071-0.

- ^ Melkote, Srinivas R.; Steeves, H. Leslie (2001). Communication for development in the Third World: theory and practice for empowerment. Sage Publications. p. 21. ISBN 0-7619-9476-9.

- ^ Provizer, Norman W. (1978). Analyzing the Third World: essays from Comparative politics. Transaction Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 0-87073-943-3.

- ^ a b c Leonard, Thomas M. (2006). "Third World". Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Vol. 3. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1542–3. ISBN 0-87073-943-3. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ a b c "Three World Model". University of Wisconsin Eau Claire. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Leonard, Thomas M. (2006). "Third World". Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Vol. 3. Taylor & Francis. p. 3. ISBN 0-87073-943-3. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "Fall of the Soviet Union". The Cold War Museum. 2008. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ a b Hinds, Lynn (1991). The Cold War as Rhetoric: The Beginnings, 1945–1950. New York: Praeger Publishers. p. 129. ISBN 0-275-93578-7.

- ^ Bonds, John (2002). Bipartisan Strategy: Selling the Marshall Plan. Westport: Praeger. p. 15. ISBN 0-275-97804-4.

- ^ Powaski, Ronald (1998). The Cold War: The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917–1991. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 74. ISBN 0-19-507851-9.

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen (1998). Rise to Globalism. New York: Longman. p. 179. ISBN 0-14-026831-6.

- ^ "THE COLD WAR (1945–1990)". U.S. Department of Energy – Office of History and Heritage Resources. 2003. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen (1998). Rise to Globalism. New York: Longman. p. 215. ISBN 0-14-026831-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Diamond, Jared (2005). Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. New York: Penguin (Non-Classics). pp. 495–496. ISBN 0-14-303655-6.

- ^ "A World Transformed: What Are the Top 30 Innovations of the Last 30 Years?". Knowledge@Wharton. February 18, 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Gleick, Peter (August 12, 2002), "Dirty Water: Estimated Deaths from Water-Related Disease 2000–2020" (PDF), Pacific Institute Research Report: 2, archived (PDF) from the original on May 4, 2005

- ^ "Malaria (Fact Sheet)". World Health Organization. January 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "International Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers". 4 October 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "Global warming: Each country's share of CO2". Union of Concerned Scientists. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Abbasi, Naseema (2004). Renewable Energy Resources and Their Environmental Impact. PHI Learning Pvt. p. vii. ISBN 81-203-1902-8.

- ^ a b Singer, Siegfried Fred; Avery, Dennis T. (2007). Unstoppable Global Warming: Every 1,500 Years. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 59. ISBN 9780742551244.

- ^ a b c Darby, Phillip (2000). At the Edge of International Relations: Postcolonialism, Gender, and Dependency. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 33. ISBN 0-8264-4719-8.

- ^ Hinds, Lynn Boyd; Windt, Theodore (1991). The Cold War as Rhetoric: The Beginnings, 1945–1950. New York: Praeger Publishers. p. 129. ISBN 0-275-93578-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Weber, Cynthia (2005). International Relations Theory: A Critical Introduction. Routledge. pp. 153–154. ISBN 0-415-34208-2.

- ^ Osland, Joyce S. (June 2003). "Broadening the Debate: The Pros and Cons of Globalization". Journal of Management Inquiry. 12 (2). Sage Publications: 137–154. doi:10.1177/1056492603012002005. S2CID 14617240. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Aucoin, Danielle (2000). "Globalization: The European Union as a Model". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d "The European Union: A Guide for Americans". pp. 2–3. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "Managing Globalization". pp. 1–2. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Europe as an expression of the soul, prime minister of Italy

- ^ "European Commission". Archived from the original on August 28, 2006. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ a b Barnet, Richard; Cavanagh, John (1994). Global Dreams: Imperial Corporations and the New World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 250. ISBN 9780671633776.

- ^ Barnet, Richard; Cavanagh, John (1994). Global Dreams: Imperial Corporations and the New World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 354. ISBN 9780671633776.

- ^ a b Thurow, Lester C. "Globalization: The Product of a Knowledge-Based Economy". Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ Grossman, Gene M; Helpman, Elhanan (2005). "Outsourcing in a Global Economy" (PDF). The Review of Economic Studies. 72 (1): 135–159. doi:10.1111/0034-6527.00327. JSTOR 3700687.

- ^ a b c Quinn, J. B. "Strategic Outsourcing" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "Outsourcing – What is Outsourcing?", Sourcingmag.com

- ^ a b "http://www.international.ucla.edu/media/files/GlobalUnequal_10_252.pdf"

- ^ Kansal, Purva; Kaushik, Amit Kumar (January 2006). Offshore Outsourcing: An E-Commerce Reality (Opportunity for Developing Countries). Idea Group Inc (IGI). ISBN 9781591403548. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "U.S. Trade with Developing Countries and Wage Inequality" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-23.

First World

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Historical Context

Cold War Definition and Coinage

The Cold War denoted a sustained period of intense geopolitical, ideological, and military antagonism between the United States and its capitalist allies, primarily in Western Europe and the Asia-Pacific, and the Soviet Union with its communist satellite states in Eastern Europe and beyond, lasting from approximately 1947 until the Soviet collapse in 1991. This rivalry emerged in the immediate aftermath of World War II, as wartime cooperation dissolved amid irreconcilable differences over the political organization of liberated Europe, spheres of influence in Asia, and the fundamental incompatibility between liberal democratic capitalism and Marxist-Leninist totalitarianism.[8] Key manifestations included proxy conflicts such as the Korean War (1950–1953) and Vietnam War (1955–1975), a nuclear arms race peaking with mutual assured destruction doctrines by the 1960s, espionage activities, and ideological propaganda battles, all conducted without direct superpower combat to avoid catastrophic escalation.[9] The conflict's stakes were global, with both sides seeking to expand influence through alliances like NATO (formed 1949) for the West and the Warsaw Pact (1955) for the East, while competing for allegiance from decolonizing nations in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The phrase "Cold War" captured the absence of open hostilities, distinguishing it from "hot" wars involving direct armed clashes, and was initially employed to evoke a state of frozen tension akin to undeclared conflict.[10] British author George Orwell introduced the term in his October 19, 1945, essay "You and the Atom Bomb," forecasting a nuclear-armed impasse where superpowers would maintain peace through terror rather than alliance, writing of "a 'peace that is no peace'—that is to say, a state of continuous cold war."[11] The expression gained widespread currency in 1947: financier and presidential advisor Bernard Baruch used it in an April 16 speech to the South Carolina House of Representatives, warning of "the struggle [that] will be waged with atomic bombs" unless ideological divides were addressed, thereby popularizing it in American discourse.[12] Concurrently, journalist Walter Lippmann applied it in his book The Cold War (published November 1947), framing the U.S.-Soviet contest as an existential ideological duel requiring containment of Soviet expansionism.[13] These usages reflected early recognition among Western intellectuals and policymakers of the era's peculiar dynamics, rooted in power balances rather than immediate conquest. This binary superpower framework underpinned the mid-20th-century "three worlds" paradigm, wherein the "First World" designated the U.S.-led bloc of industrialized, market-oriented democracies committed to containing communism, contrasting with the "Second World" of Soviet-aligned planned economies and the "Third World" of neutral or developing states maneuvering between the poles. The classification, formalized in the 1950s amid decolonization and Bandung Conference alignments (1955), highlighted how Cold War pressures bifurcated global order into opposing ideological camps, with First World nations prioritizing private enterprise, rule of law, and anti-totalitarian alliances as bulwarks against Soviet encirclement.[14] Empirical divergences in governance—evident in the West's post-1945 economic recoveries via Marshall Plan aid (1948–1952, totaling $13 billion) versus Eastern Europe's centralized controls—reinforced the term's descriptive utility for analysts tracking alliance-based prosperity gradients.[9]Alignment with Capitalism and NATO

![Cold War alliances mid-1975][float-right] The First World encompassed nations that adopted capitalist economic systems, emphasizing private property rights, market-driven allocation of resources, and limited government intervention in economic affairs, in contrast to the centrally planned economies of the Second World.[6] [15] These countries, including the United States, Canada, and Western European states, pursued policies fostering entrepreneurship, innovation, and trade liberalization, which underpinned their industrial and technological advancement during the Cold War era.[3] Politically and militarily, First World alignment was epitomized by adherence to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), established on April 4, 1949, by twelve founding members—Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States—to provide collective defense against potential Soviet aggression.[16] [17] NATO's Article 5 committed members to treat an attack on one as an attack on all, reinforcing a unified front that extended beyond Europe to include aligned non-members like Japan and Australia through bilateral security treaties and shared ideological opposition to communism.[15] This alliance structure not only deterred expansionism from the Warsaw Pact but also facilitated economic cooperation, such as through the Marshall Plan, which aided postwar reconstruction in capitalist-aligned Europe.[16] While NATO membership was a core indicator for European and North American First World countries, the broader category included Pacific allies integrated via U.S.-centric pacts, reflecting a global commitment to democratic governance and free-market principles over totalitarian alternatives.[3] [6] This alignment contributed to sustained economic growth, with First World GDP per capita significantly outpacing the Second World by the 1970s, attributable to institutional frameworks prioritizing individual liberty and competitive markets.[15]Evolution and Redefinition

Post-Cold War Shifts

The dissolution of the Soviet Union on December 26, 1991, eliminated the Second World bloc of communist states, fundamentally altering the geopolitical framework that defined the First World during the Cold War.[18] This event, coupled with the Warsaw Pact's dissolution in 1991, removed the ideological and military antagonism that had anchored the First World's identity as the U.S.-led capitalist alliance.[19] Former Eastern Bloc countries faced acute economic contraction initially, with gross national product falling by about 20% across Soviet republics between 1989 and 1991 due to the abrupt end of central planning and subsidies.[20] In response, many Central and Eastern European states pursued "shock therapy" reforms, privatizing state assets, liberalizing prices, and stabilizing currencies to transition to market economies, which laid the groundwork for integration into First World institutions.[21] NATO expanded eastward, admitting the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland in 1999, followed by Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia in 2004, effectively extending the alliance's security umbrella to former adversaries and reinforcing democratic alignments.[22] The European Union underwent its largest enlargement on May 1, 2004, incorporating ten nations—including eight post-communist states such as the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia—accelerating economic convergence through single-market access and structural funds.[23] These integrations blurred the original First World boundaries, as transitioning economies adopted capitalist institutions and achieved GDP growth rates averaging 4-6% annually in the decade post-accession, outpacing non-integrated peers like those in the Commonwealth of Independent States.[24] Consequently, the term "First World" shifted from a primarily geopolitical designation—encompassing NATO-aligned democracies—to an economic one, denoting industrialized nations with high per capita incomes (typically above $12,000), advanced infrastructure, and stable governance, often overlapping with OECD membership or World Bank high-income classifications.[1][6] This evolution reflects empirical validation of market-oriented policies, as integrated states like Poland saw real GDP per capita rise from $1,700 in 1990 to over $18,000 by 2021, contrasting with slower recoveries in more state-controlled former Soviet republics.[24] However, divergences persisted: Russia and Belarus retained authoritarian structures and resource-dependent economies, resisting full First World convergence, while outliers like the Baltic states fully aligned through euro adoption and rule-of-law reforms.[21] In academic and policy discourse, the post-Cold War First World concept increasingly prioritizes causal factors like property rights and open trade over mere alliance history, though legacy usages occasionally invoke original ideological contrasts to critique persistent global inequalities.[25] This reorientation underscores how institutional adoption, rather than geography, drives prosperity, with empirical data showing faster human development gains in reformed ex-communist states compared to non-aligned developing economies.[23]Modern Indicators and Membership

In contemporary usage, the concept of the First World has transitioned from Cold War-era geopolitical affiliations to empirical measures of advanced socioeconomic development, emphasizing sustained high performance in human welfare, economic productivity, and institutional stability. Primary indicators include the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI), where scores of 0.800 or higher denote "very high human development," reflecting achievements in life expectancy, education, and gross national income per capita.[26] As of the 2025 UN Human Development Report, 74 countries meet this threshold, though First World designation prioritizes those with consistent historical alignment to market-oriented systems and democratic governance over transient resource-driven gains.[27] Complementary metrics encompass World Bank classifications of high-income economies, defined by GNI per capita exceeding $13,845 (Atlas method) for fiscal year 2025, alongside low infant mortality rates below 5 per 1,000 live births and adult literacy rates approaching 100%.[28] These indicators underscore causal linkages between institutional factors—such as secure property rights and innovation ecosystems—and enduring prosperity, rather than nominal aggregates alone.[1] Membership remains informal and contested, lacking a centralized authority, but core constituents align with OECD nations exhibiting very high HDI scores, excluding those reliant on extractive economies without broader structural reforms. Canonical examples include the United States (HDI 0.938 in 2023 data), Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany (HDI 0.959), Japan, Australia, and New Zealand, which collectively represent industrialized democracies with GDP per capita exceeding $40,000 in purchasing power parity terms as of 2024 estimates.[29][30] Expanded lists from analytical sources incorporate East Asian advanced economies like South Korea (HDI 0.937) and Singapore, which have achieved First World status through export-led growth and legal frameworks fostering entrepreneurship since the late 20th century.[6] Conversely, high-income states such as Saudi Arabia or Qatar, despite GNI per capita above $50,000, are typically excluded due to authoritarian governance and dependence on hydrocarbon rents, which empirical studies link to volatility rather than replicable development models.[3]| Indicator | Threshold for First World Alignment | Example Countries Meeting Criteria (2025 Data) |

|---|---|---|

| HDI | ≥0.800 (very high) | Iceland (0.972), Norway (0.970), Switzerland (0.970)[31] |

| GNI per Capita (World Bank) | >$13,845 | United States, Germany, Australia[28] |

| OECD Membership | 38 member states, focused on high living standards | Japan, South Korea, most EU nations (excl. emerging members like Mexico)[32] |

Core Characteristics

Economic Metrics and Prosperity

First World countries, encompassing advanced economies such as those in Western Europe, North America, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand, demonstrate elevated economic prosperity through metrics like gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. According to International Monetary Fund data from the October 2025 World Economic Outlook, GDP per capita in purchasing power parity terms for advanced economies averages 73,770 international dollars, substantially exceeding the global figure of approximately 18,420 international dollars. This disparity underscores the concentration of economic output in these nations, which account for a disproportionate share of global wealth despite comprising a small fraction of the world's population.[34] Extreme poverty rates in these countries remain negligible, typically below 1% when measured against the World Bank's $2.15 daily threshold, in contrast to rates exceeding 20% in many low-income developing nations and a global average projected at 9.9% for 2025.[35] Relative poverty, defined nationally (e.g., 50% of median income), affects 10-15% of populations in OECD members, yet absolute living standards far surpass those elsewhere due to high median household incomes often exceeding $40,000 annually.[36] These outcomes reflect sustained productivity growth, with OECD labor productivity levels in 2024 averaging over twice the global mean, driven by capital-intensive industries and technological adoption.[37] Innovation metrics further highlight prosperity, as First World nations dominate global rankings. The 2025 Global Innovation Index places Switzerland, Sweden, the United States, and the United Kingdom among the top performers, with these countries leading in patents, R&D expenditure (averaging 2.5-3% of GDP), and high-tech exports.[38] Such indicators correlate with wealth generation, as innovation fosters productivity gains and new markets, contributing to real GDP per capita growth rates of 1-2% annually in advanced economies post-2020.[39]| Metric | Advanced Economies | Global Average |

|---|---|---|

| GDP per capita (PPP, intl. $, 2025) | 73,770 | 18,420 |

| Extreme Poverty Rate (%, 2025 est.) | <1 | 9.9 |

| HDI Value (2023) | 0.90+ (very high category) | 0.739 |

Political and Institutional Features

First World countries are characterized by stable liberal democratic systems featuring regular, competitive elections with universal suffrage, multi-party competition, and mechanisms to ensure electoral integrity such as independent electoral commissions. These systems prioritize representative governance, where elected officials are accountable to constituents through term limits and recall processes in some cases. The V-Dem Institute's 2023 Liberal Democracy Index scores all top-ranked countries—such as Norway (0.92), Sweden (0.90), and Canada (0.88)—as exemplifying these features, reflecting high levels of electoral democracy and liberal components like constraints on executive power. A core institutional feature is the separation of powers, with independent legislatures, executives, and judiciaries that check each other to prevent authoritarianism. Constitutions or foundational laws explicitly delineate these branches, often including bills of rights protecting freedoms of expression, association, and religion. The United States Constitution of 1787 established this model, influencing many others, while parliamentary systems in nations like the United Kingdom and Australia adapt it through conventions and statutory safeguards. Empirical assessments, including the World Bank's Worldwide Governance Indicators for 2023, show First World nations scoring above 1.5 standard deviations on voice and accountability and government effectiveness metrics, far exceeding global averages. Rule of law prevails through impartial judiciaries that enforce contracts, protect property rights, and prosecute corruption without favoritism. These institutions foster trust essential for social cohesion and investment. The World Justice Project's 2023 Rule of Law Index ranks Denmark (0.90), Norway (0.89), and Finland (0.87) highest globally, attributing their success to accessible courts, absence of discrimination, and constraints on government powers. Corruption remains minimal due to robust transparency laws, independent anti-corruption agencies, and free media scrutiny, though challenges persist in procurement and lobbying. Transparency International's 2023 Corruption Perceptions Index assigns scores of 80 or above to 15 First World countries, including New Zealand (85), Singapore (83, despite its hybrid system), and the Netherlands (80), correlating with institutional strength rather than mere affluence. Multiple studies link these low corruption levels to decentralized power structures and cultural norms emphasizing accountability. Many First World states participate in supranational bodies that reinforce democratic norms, such as the European Union, which requires adherence to rule of law for membership, and NATO, whose Article 5 embodies collective defense rooted in shared democratic values. The OECD's 2023 Government at a Glance report highlights how these countries maintain high public trust in institutions—averaging 50-60%—through participatory mechanisms like referendums and ombudsmen.Achievements and Causal Factors

Drivers of Development

Secure property rights and the rule of law have served as foundational drivers of sustained economic development in First World nations by incentivizing investment, innovation, and long-term planning. Empirical analyses indicate that inclusive economic institutions, which protect property rights and enforce contracts impartially, explain much of the divergence in prosperity between developed and underdeveloped regions, as they align individual incentives with productive activities rather than extraction or rent-seeking.[42] [43] For instance, cross-country regressions show that stronger rule-of-law indices correlate with higher GDP per capita growth rates, mitigating risks of expropriation and violence while fostering capital accumulation.[44] These institutional frameworks emerged prominently in Western Europe during the Enlightenment and were exported through settler colonies, contributing to the high-income trajectories of nations like those in North America and Oceania.[45] Market-oriented capitalism has further propelled development by promoting competition, resource allocation efficiency, and entrepreneurial risk-taking, hallmarks of First World economies. Data from economic freedom indices demonstrate that countries with fewer government interventions in markets—such as lower tariffs, regulatory burdens, and subsidies—exhibit faster productivity growth and higher living standards, as evidenced by the post-World War II boom in Western capitalist states averaging annual GDP growth of 4-5% through the 1960s.[46] [47] Free markets enable price signals to guide innovation and specialization, with historical evidence from the Industrial Revolution showing that private ownership of production factors in Britain and the United States accelerated technological adoption and wealth creation compared to mercantilist systems elsewhere.[48] While critiques from interventionist perspectives exist, econometric studies confirm that liberalization episodes, such as those in the 1980s under Reagan and Thatcher, yielded sustained output gains without the stagnation seen in more controlled economies.[49] Investment in research and development (R&D), supported by institutional stability and market incentives, has been a critical engine of productivity gains in OECD countries, which comprise the core of the First World. Gross domestic spending on R&D in these nations averaged 2.5-3% of GDP in 2022, correlating with patent outputs and total factor productivity increases; for example, the United States and Germany attribute over 50% of post-1950 growth to innovation-driven sectors like information technology and manufacturing.[50] [51] Panel data across 16 OECD members reveal a robust positive relationship between R&D intensity and labor productivity, with private-sector funding—facilitated by intellectual property protections—amplifying returns through spillovers in knowledge economies.[52] This dynamic underscores how First World development relies on continuous technological advancement rather than resource endowments alone. Cultural elements, such as the Protestant work ethic emphasizing diligence, thrift, and deferred gratification, have been posited as complementary drivers, particularly in Northern European and Anglo-Saxon societies. Max Weber's thesis links Calvinist doctrines to the rise of capitalism by instilling a rational orientation toward worldly success as a sign of divine favor, with historical correlations showing Protestant-majority regions outperforming Catholic counterparts in early industrialization metrics like urbanization and literacy rates by the 19th century.[53] Empirical tests, however, find the association positive but not overwhelmingly causal, as economic development itself reinforces work ethic values in a feedback loop; nonetheless, surveys indicate higher Protestant adherence aligns with stronger individual productivity norms in developed contexts.[54] These factors, intertwined with institutional and market mechanisms, explain the empirical superiority of First World outcomes without relying on exogenous advantages like geography.Empirical Evidence of Superior Outcomes

First World countries, characterized by high levels of economic freedom, rule of law, and market-oriented institutions, consistently demonstrate superior economic performance. Advanced economies, which align closely with First World classifications, recorded an average GDP per capita (PPP) of $73,770 in 2024, compared to $18,420 for emerging and developing economies.[55] High-income countries averaged over $50,000 in GDP per capita (PPP) as of 2023, far exceeding the global average of approximately $22,000.[56] This disparity reflects sustained productivity gains from property rights protection and open markets, as evidenced by the strong positive correlation between economic freedom scores and per capita income in the Heritage Foundation's Index, where "free" economies average over twice the income of "repressed" ones.[57] Health outcomes further underscore these advantages. Life expectancy at birth in OECD countries, predominantly First World nations, averaged 80.3 years in 2021, rebounding from COVID-19 impacts but remaining well above the global average of 73 years in 2023.[58][59] Infant mortality rates in high-income countries stood at around 4-6 deaths per 1,000 live births in recent years, contrasted with over 40 in low-income nations, enabling near-universal survival rates for newborns through advanced medical infrastructure and sanitation.[60][61] Educational attainment shows similar patterns. In the 2022 PISA assessments, OECD countries averaged scores of about 480-500 across math, reading, and science, outperforming non-OECD participants by 50-100 points on average, with top First World performers like Singapore and Estonia exceeding 550.[62] This gap correlates with higher investments in merit-based systems and literacy rates approaching 100% in developed nations versus 60-80% in many developing ones.[63] The Human Development Index (HDI) aggregates these metrics, with First World countries dominating the very high category (0.900+), such as Switzerland at 0.967 and Norway at 0.966 in 2023, while low-development nations like South Sudan scored below 0.400.[29] Innovation metrics reinforce this, as high-income countries filed over 90% of global patents in 2023, with rates per capita exceeding 200 applications per million people versus under 5 in low-income groups.[64] These outcomes stem from institutional factors enabling capital accumulation and technological diffusion, rather than resource endowments alone, as resource-rich but institutionally weak states lag behind.[57]| Metric | First World/High-Income Average | Developing/Low-Income Average | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDP per capita (PPP, 2024) | $73,770 | $18,420 | IMF[55] |

| Life Expectancy (2023) | 80+ years (OECD) | ~65-70 years | OECD/OWID[58][59] |

| Infant Mortality (per 1,000, recent) | 4-6 | 40+ | World Bank/UNICEF[60][61] |

| PISA Math Score (2022) | ~480 (OECD avg.) | ~400 (non-OECD avg.) | OECD[62] |

| HDI (2023) | 0.900-0.970 | 0.400-0.550 | UNDP[29] |