Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Three-world model

View on Wikipedia

| Eastern Bloc |

|---|

|

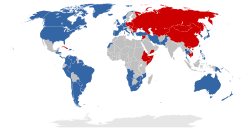

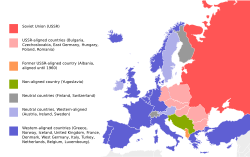

The terms First World, Second World, and Third World were originally used to divide the world's nations into three categories. The complete overthrow of the pre–World War II status quo left two superpowers (the United States and the Soviet Union) vying for ultimate global supremacy, a struggle known as the Cold War. They created two camps, known as blocs. These blocs formed the basis of the concepts of the First and Second Worlds.[1] The Third World consisted of those countries that were not closely aligned with either bloc.

History

[edit]Cold War

[edit]Early in the Cold War era, NATO and the Warsaw Pact were created by the United States and the Soviet Union, respectively. They were also referred to as the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The circumstances of these two blocs were so different that they were essentially two worlds, however, they were not numbered first and second.[2][3][4] The onset of the Cold War is marked by Winston Churchill's famous "Iron Curtain" speech.[5] In this speech, Churchill describes the division of the West and East to be so solid that it could be called an iron curtain.[5]

In 1952, the French demographer Alfred Sauvy coined the term Third World in reference to the three estates in pre-revolutionary France.[6] The first two estates being the nobility and clergy and everybody else comprising the third estate.[6] He compared the capitalist world (i.e., First World) to the nobility and the communist world (i.e., Second World) to the clergy. The First World countries were characterized by economic prosperity, technological advancement, and political stability, whereas the Second World countries were characterized by state-controlled economies and centralized political structures. Just as the third estate comprised everybody else, Sauvy called the Third World all the countries that were not in this Cold War division, i.e., the unaligned and uninvolved states in the "East–West Conflict."[6][4] The Third World countries are often described as developing nations with diverse economic, social, and political conditions. With the coining of the term Third World directly, the first two groups came to be known as the "First World" and "Second World," respectively. Here the three-world system emerged.[4]

However, Shuswap Chief George Manuel presented a critique of the three-worlds model, considering it to be outdated. In his 1974 book The Fourth World: An Indian Reality, he describes the emergence of the Fourth World while coining the term. The fourth world refers to "nations," e.g., cultural entities and ethnic groups, of indigenous people who do not compose states in the traditional sense.[7] Rather, they live within or across state boundaries (see First Nations). One example is the Native Americans of North America, Central America, and the Caribbean.[7]

Post Cold War

[edit]With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Eastern Bloc ceased to exist; with it, so did all applicability of the Three-world model.[8]

However, Third World is still used as a term for the traditionally less-developed world (e.g. Africa).[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Gaddis, John (1998). We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-19-878071-0.

- ^ Melkote, Srinivas R.; Steeves, H. Leslie (2001). Communication for development in the Third World: theory and practice for empowerment. Sage Publications. p. 21. ISBN 0-7619-9476-9. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Provizer, Norman W. (1978). Analyzing the Third World: essays from Comparative politics. Transaction Publishers. p. 3. ISBN 0-87073-943-3. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Leonard, Thomas M. (2006). "Third World". Encyclopedia of the Developing World. Vol. 3. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1542–3. ISBN 0-87073-943-3. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ a b "Winston Churchill "Iron Curtain"". The History Place. Archived from the original on 8 May 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ a b c "Three Worlds Model". University of Wisconsin Eau Claire. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ a b "First, Second and Third World". One World – Nations Online. July 2009. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ "Fall of the Soviet Union". The Cold War Museum. 2008. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2009.