Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Languages of Europe

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2019) |

There are over 250 languages indigenous to Europe, and most belong to the Indo-European language family.[1][2] Out of a total European population of 744 million as of 2018, some 94% are native speakers of an Indo-European language. The three largest phyla of the Indo-European language family in Europe are Romance, Germanic, and Slavic; they have more than 200 million speakers each, and together account for close to 90% of Europeans.

Smaller phyla of Indo-European found in Europe include Hellenic (Greek, c. 13 million), Baltic (c. 4.5 million), Albanian (c. 7.5 million), Celtic (c. 4 million), and Armenian (c. 4 million). Indo-Aryan, though a large subfamily of Indo-European, has a relatively small number of languages in Europe, and a small number of speakers (Romani, c. 1.5 million). However, a number of Indo-Aryan languages not native to Europe are spoken in Europe today.[2]

Of the approximately 45 million Europeans speaking non-Indo-European languages, most speak languages within either the Uralic or Turkic families. Still smaller groups — such as Basque (language isolate), Semitic languages (Maltese, c. 0.5 million), and various languages of the Caucasus — account for less than 1% of the European population among them. Immigration has added sizeable communities of speakers of African and Asian languages, amounting to about 4% of the population,[3] with Arabic being the most widely spoken of them.

Five languages have more than 50 million native speakers in Europe: Russian, German, French, Italian, and English. Russian is the most-spoken native language in Europe,[4] and English has the largest number of speakers in total, including some 200 million speakers of English as a second or foreign language. (See English language in Europe.)

Indo-European languages

[edit]The Indo-European language family is descended from Proto-Indo-European, which is believed to have been spoken thousands of years ago. Early speakers of Indo-European daughter languages most likely expanded into Europe with the incipient Bronze Age, around 4,000 years ago (Bell-Beaker culture).

Germanic

[edit]

The Germanic languages make up the predominant language family in Western, Northern and Central Europe. It is estimated that over 500 million Europeans are speakers of Germanic languages,[5] the largest groups being German (c. 95 million), English (c. 400 million)[citation needed], Dutch (c. 24 million), Swedish (c. 10 million), Danish (c. 6 million), Norwegian (c. 5 million)[6] and Limburgish (c. 1.3 million).[citation needed]

There are two extant major sub-divisions: West Germanic and North Germanic. A third group, East Germanic, is now extinct; the only known surviving East Germanic texts are written in the Gothic language. West Germanic is divided into Anglo-Frisian (including English), Low German, Low Franconian (including Dutch) and High German (including Standard German).[7]

Anglo-Frisian

[edit]The Anglo-Frisian language family is now mostly represented by English (Anglic), descended from the Old English language spoken by the Anglo-Saxons:

- English, the main language of the United Kingdom and the most widespread language in the Republic of Ireland, also spoken as a second or third language by many Europeans.[8]

- Scots, spoken in Scotland and Ulster, recognized by some as a language and by others as a dialect of English[9] (not to be confused with Scots-Gaelic of the Celtic language family).

The Frisian languages are spoken by about 400,000 (as of 2015[update]) Frisians,[10][11] who live on the southern coast of the North Sea in the Netherlands and Germany. These languages include West Frisian, East Frisian (of which the only surviving dialect is Saterlandic) and North Frisian.[10]

Dutch

[edit]Dutch is spoken throughout the Netherlands, the northern half of Belgium, as well as the Nord-Pas de Calais region of France. The traditional dialects of the Lower Rhine region of Germany are linguistically more closely related to Dutch than to modern German. In Belgian and French contexts, Dutch is sometimes referred to as Flemish. Dutch dialects are numerous and varied.[12]

German

[edit]German is spoken throughout Germany, Austria, Liechtenstein, much of Switzerland, northern Italy (South Tyrol), Luxembourg, the East Cantons of Belgium and the Alsace and Lorraine regions of France.[13]

There are several groups of German dialects:

- High German includes several dialect families:

- Standard German

- Central German dialects, spoken in central Germany and including Luxembourgish

- High Franconian, a family of transitional dialects between Central and Upper High German

- Upper German, including Bavarian and Swiss German

- Yiddish is a Jewish language developed in Germany and Eastern Europe. It shares many features of High German dialects and Hebrew.[14]

Low German is spoken in various regions throughout Northern Germany and the northern and eastern parts of the Netherlands.[15] It may be separated into West Low German and East Low German.[16]

North Germanic (Scandinavian)

[edit]The North Germanic languages are spoken in Nordic countries and include Swedish (Sweden and parts of Finland), Danish (Denmark), Norwegian (Norway), Icelandic (Iceland), Faroese (Faroe Islands), and Elfdalian (in a small part of central Sweden).[17]

English has a long history of contact with Scandinavian languages, given the immigration of Scandinavians early in the history of Britain, and shares various features with the Scandinavian languages.[18] Even so, especially Dutch and Swedish, but also Danish and Norwegian, have strong vocabulary connections to the German language.[19][20][21]

Romance

[edit]

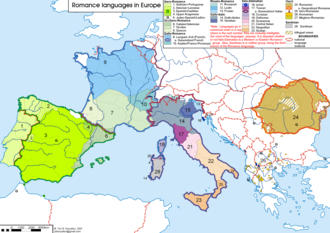

Roughly 215 million Europeans (primarily in Southern and Western Europe) are native speakers of Romance languages, the largest groups including:[citation needed]

French (c. 72 million), Italian (c. 65 million), Spanish (c. 40 million), Romanian (c. 24 million), Portuguese (c. 10 million), Catalan (c. 7 million), Neapolitan (c. 6 million), Sicilian (c. 5 million), Venetian (c. 4 million), Galician (c. 2 million), Sardinian (c. 1 million),[22][23][24] Occitan (c. 500,000), besides numerous smaller communities.

The Romance languages evolved from varieties of Vulgar Latin spoken in the various parts of the Roman Empire in Late Antiquity. Latin was itself part of the (otherwise extinct) Italic branch of Indo-European.[25] Romance languages are divided phylogenetically into Italo-Western, Eastern Romance (including Romanian) and Sardinian. The Romance-speaking area of Europe is occasionally referred to as Latin Europe.[26]

Italo-Western can be further broken down into the Italo-Dalmatian languages (sometimes grouped with Eastern Romance), including the Tuscan-derived Italian and numerous local Romance languages in Italy as well as Dalmatian, and the Western Romance languages. The Western Romance languages in turn separate into the Gallo-Romance languages, including Langues d'oïl such as French, the Francoprovencalic languages Arpitan and Faetar, the Rhaeto-Romance languages, and the Gallo-Italic languages; the Occitano-Romance languages, grouped with either Gallo-Romance or East Iberian, including Occitanic languages such as Occitan and Gardiol, and Catalan; Aragonese, grouped in with either Occitano-Romance or West Iberian, and finally the West Iberian languages, including the Astur-Leonese languages, the Galician-Portuguese languages, and the Castilian languages.[citation needed]

Slavic

[edit]

Slavic languages are spoken in large areas of Southern, Central and Eastern Europe. An estimated 315 million people speak a Slavic language,[27] the largest groups being Russian (c. 110 million in European Russia and adjacent parts of Eastern Europe, Russian forming the largest linguistic community in Europe), Polish (c. 40 million[28]), Ukrainian (c. 33 million[29]), Serbo-Croatian (c. 18 million[30]), Czech (c. 11 million[31]), Bulgarian (c. 8 million[32]), Slovak (c. 5 million[33]), Belarusian (c. 3.7 million[34]), Slovene (c. 2.3 million[35]) and Macedonian (c. 1.6 million[36]).

Phylogenetically, Slavic is divided into three subgroups:[37]

- West Slavic includes Polish, Polabian, Czech, Knaanic, Slovak, Lower Sorbian, Upper Sorbian, Silesian and Kashubian.

- East Slavic includes Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian, Ruthenian, and Rusyn.

- South Slavic includes Slovene and Serbo-Croatian in the southwest and Bulgarian, Macedonian and Church Slavonic (a liturgical language) in the southeast, each with numerous distinctive dialects. South Slavic languages constitute a dialect continuum where standard Slovene, Macedonian and Bulgarian are each based on a distinct dialect, whereas pluricentric Serbo-Croatian boasts four mutually intelligible national standard varieties all based on a single dialect, Shtokavian.

Others

[edit]- Greek (c. 13 million) is the official language of Greece and Cyprus, and there are Greek-speaking enclaves in Albania, Bulgaria, Italy, North Macedonia, Romania, Georgia, Ukraine, Lebanon, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and Turkey, and in Greek communities around the world. Dialects of modern Greek that originate from Attic Greek (through Koine and then Medieval Greek) are Cappadocian, Pontic, Cretan, Cypriot, Katharevousa, and Yevanic.[citation needed]

- Italiot Greek is, debatably, a Doric dialect of Greek. It is spoken in southern Italy only, in the southern Calabria region (as Grecanic)[38][39][40][41][42] and in the Salento region (as Griko). It was studied by the German linguist Gerhard Rohlfs during the 1930s and 1950s.[43]

- Tsakonian is a Doric dialect of the Greek language spoken in the lower Arcadia region of the Peloponnese around the village of Leonidio[44]

- The Baltic languages are spoken in Lithuania (Lithuanian (c. 3 million), Samogitian) and Latvia (Latvian (c. 1.5 million), Latgalian). Samogitian and Latgalian used to be considered dialects of Lithuanian and Latvian respectively.[citation needed]

- Albanian (c. 7.5 million) has two major dialects, Tosk Albanian and Gheg Albanian. It is spoken in Albania and Kosovo, neighboring North Macedonia, Serbia, Italy, and Montenegro. It is also widely spoken in the Albanian diaspora.[50]

- Armenian (c. 7 million) has two major forms, Western Armenian and Eastern Armenian. It is spoken in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (Samtskhe-Javakheti) and Abkhazia, also Russia, France, Italy, Turkey, Greece, and Cyprus. It is also widely spoken in the Armenian Diaspora. [citation needed]

- There are six living Celtic languages, spoken in areas of northwestern Europe dubbed the "Celtic nations". All six are members of the Insular Celtic family, which in turn is divided into:

- Brittonic family: Welsh (Wales, c. 843,500[51]), Cornish (Cornwall, c. 500[52]) and Breton (Brittany, c. 206,000[53])

- Goidelic family: Irish (Ireland, c. 1.7 million[54]), Scottish Gaelic (Scotland, c. 57,400[55]), and Manx (Isle of Man, 1,660[56])

- Continental Celtic languages had previously been spoken across Europe from Iberia and Gaul to Asia Minor, but became extinct in the first millennium CE.[57][58]

- The Indo-Aryan languages have one major representative: Romani (c. 4.6 million speakers[59]), introduced in Europe during the late medieval period. Lacking a nation state, Romani is spoken as a minority language throughout Europe.[59]

- The Iranian languages in Europe are natively represented in the North Caucasus, notably with Ossetian[60] (c. 600,000).[citation needed]

Uralic languages

[edit]

The Uralic language family is native to northern Eurasia. Finnic languages include Finnish (c. 5 million) and Estonian (c. 1 million), as well as smaller languages such as Kven (c. 8,000). Other languages of the Finno-Permic branch of the family include e.g. Mari (c. 400,000), and the Sami languages (c. 30,000).[61]

The Ugric branch of the language family is represented in Europe by the Hungarian language (c. 13 million), historically introduced with the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin of the 9th century.[citation needed] The Samoyedic Nenets language is spoken in Nenets Autonomous Okrug of Russia, located in the far northeastern corner of Europe (as delimited by the Ural Mountains).[citation needed]

Semitic languages

[edit]

- Maltese (c. 500,000) is a Semitic language with Romance and Germanic influences, spoken in Malta.[62][63][64][65] It is based on Sicilian Arabic, with influences from Sicilian, Italian, French and, more recently, English. It is the only Semitic language whose standard form is written in Latin script. It is also the second smallest official language of the EU in terms of speakers (after Irish), and the only official Semitic language within the EU.[citation needed]

- Cypriot Maronite Arabic (also known as Cypriot Arabic) is a variety of Arabic spoken by Maronites in Cyprus. Most speakers live in Nicosia, but others are in the communities of Kormakiti and Lemesos. Brought to the island by Maronites fleeing Lebanon over 700 years ago, this variety of Arabic has been influenced by Greek in both phonology and vocabulary, while retaining certain unusually archaic features in other respects.

- Eastern Aramaic, a Semitic language is spoken by Assyrian communities in the Caucasus and southern Russia who fled the Assyrian Genocide during World War I, and also by Assyrian communities in the Assyrian diaspora in other parts of Europe.[66]

Turkic languages

[edit]

- Oghuz languages in Europe include Turkish, spoken in East Thrace and by immigrant communities; Azerbaijani is spoken in Northeast Azerbaijan and parts of Southern Russia and Gagauz is spoken in Gagauzia.[67]

- Kipchak languages in Europe include Karaim, Crimean Tatar and Krymchak, which is spoken mainly in Crimea; Tatar, which is spoken in Tatarstan; Bashkir, which is spoken in Bashkortostan; Karachay-Balkar, which is spoken in the North Caucasus, and Kazakh, which is spoken in Northwest Kazakhstan.[67]

- Oghur languages were historically indigenous to much of Eastern Europe; however, most of them are extinct today, with the exception of Chuvash, which is spoken in Chuvashia.[68]

Other languages

[edit]- The Basque language (or Euskara, c. 750,000) is a language isolate and the ancestral language of the Basque people who inhabit the Basque Country, a region in the western Pyrenees mountains mostly in northeastern Spain and partly in southwestern France of about 3 million inhabitants, where it is spoken fluently by about 750,000 and understood by more than 1.5 million people. Basque is directly related to ancient Aquitanian, and it is likely that an early form of the Basque language was present in Western Europe before the arrival of the Indo-European languages in the area in the Bronze Age.[citation needed]

- The Northwest Caucasian family (including Abkhaz and Circassian).[citation needed][69]

- The Northeast Caucasian family, spoken mainly in the border area of the southern Russian Federation (including Dagestan, Chechnya, and Ingushetia) and northern Azerbaijan.[citation needed]

- Kalmyk is a Mongolic language, spoken in the Republic of Kalmykia, part of the Russian Federation. Its speakers entered the Volga region in the early 17th century.[70]

- Kartvelian languages (also known as South Caucasian languages), the most common of which is Georgian (c. 3.5 million), others being Mingrelian, Laz and Svan, spoken mainly in the Caucasus and Anatolia.[71]

Sign languages

[edit]Several dozen manual languages exist across Europe, with the most widespread sign language family being the Francosign languages, with its languages found in countries from Iberia to the Balkans and the Baltics. Accurate historical information of sign and tactile languages is difficult to come by, with folk histories noting the existence signing communities across Europe hundreds of years ago. British Sign Language (BSL) and French Sign Language (LSF) are probably the oldest confirmed, continuously used sign languages. Alongside German Sign Language (DGS) according to Ethnologue, these three have the most numbers of signers, though very few institutions take appropriate statistics on contemporary signing populations, making legitimate data hard to find.[citation needed]

Notably, few European sign languages have overt connections with the local majority/oral languages, aside from standard language contact and borrowing, meaning grammatically the sign languages and the oral languages of Europe are quite distinct from one another. Due to (visual/aural) modality differences, most sign languages are named for the larger ethnic nation in which they are spoken, plus the words "sign language", rendering what is spoken across much of France, Wallonia and Romandy as French Sign Language or LSF for: langue des signes française.[72]

Recognition of non-oral languages varies widely from region to region.[73] Some countries afford legal recognition, even to official on a state level, whereas others continue to be actively suppressed.[74]

Though "there is a widespread belief—among both Deaf people and sign language linguists—that there are sign language families,"[75] the actual relationship between sign languages is difficult to ascertain. Concepts and methods used in historical linguistics to describe language families for written and spoken languages are not easily mapped onto signed languages.[76] Some of the current understandings of sign language relationships, however, provide some reasonable estimates about potential sign language families:

- Francosign languages, such as LSF, ASL, Dutch Sign Language, Flemish Sign Language, and Italian Sign Language.[77]

- BANZSL languages, including British Sign Language (BSL), New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL), Australian Sign Language (Auslan), and Swedish Sign Language.[78]

- Isolate languages, such as Albanian Sign Language, Armenian Sign Language, Caucasian Sign Language, Spanish Sign Language (LSE), Turkish Sign Language (TİD), and perhaps Ghardaia Sign Language.

- Many other sign languages, such as Irish Sign Language (ISL), have unclear origins.[79]

History of standardization

[edit]Language and identity, standardization processes

[edit]In the Middle Ages the two most important defining elements of Europe were Christianitas and Latinitas.[80]

The earliest dictionaries were glossaries: more or less structured lists of lexical pairs (in alphabetical order or according to conceptual fields). The Latin-German (Latin-Bavarian) Abrogans was among the first. A new wave of lexicography can be seen from the late 15th century onwards (after the introduction of the printing press, with the growing interest in standardization of languages).[citation needed]

The concept of the nation state began to emerge in the early modern period. Nations adopted particular dialects as their national language. This, together with improved communications, led to official efforts to standardize the national language, and a number of language academies were established: 1582 Accademia della Crusca in Florence, 1617 Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft in Weimar, 1635 Académie française in Paris, 1713 Real Academia Española in Madrid. Language became increasingly linked to nation as opposed to culture, and was also used to promote religious and ethnic identity: e.g. different Bible translations in the same language for Catholics and Protestants.[citation needed]

The first languages whose standardisation was promoted included Italian (questione della lingua: Modern Tuscan/Florentine vs. Old Tuscan/Florentine vs. Venetian → Modern Florentine + archaic Tuscan + Upper Italian), French (the standard is based on Parisian), English (the standard is based on the London dialect) and (High) German (based on the dialects of the chancellery of Meissen in Saxony, Middle German, and the chancellery of Prague in Bohemia ("Common German")). But several other nations also began to develop a standard variety in the 16th century.[citation needed]

Lingua franca

[edit]Europe has had a number of languages that were considered linguae francae over some ranges for some periods according to some historians. Typically in the rise of a national language the new language becomes a lingua franca to peoples in the range of the future nation until the consolidation and unification phases. If the nation becomes internationally influential, its language may become a lingua franca among nations that speak their own national languages. Europe has had no lingua franca ranging over its entire territory spoken by all or most of its populations during any historical period. Some linguae francae of past and present over some of its regions for some of its populations are:

- Classical Greek and then Koine Greek in the Mediterranean Basin from the Athenian Empire to the Eastern Roman Empire, being replaced by Modern Greek.

- Koine Greek and Modern Greek, in the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire and other parts of the Balkans south of the Jireček Line.[81]

- Vulgar Latin and Late Latin among the uneducated and educated populations respectively of the Roman Empire and the states that followed it in the same range no later than 900 AD; Medieval Latin and Renaissance Latin among the educated populations of western, northern, central and part of eastern Europe until the rise of the national languages in that range, beginning with the first language academy in Italy in 1582/83; Neo-Latin written only in scholarly and scientific contexts by a small minority of the educated population at scattered locations over all of Europe; ecclesiastical Latin, in spoken and written contexts of liturgy and church administration only, over the range of the Roman Catholic Church.[citation needed]

- Old Occitan in central and southern France, north-western Italy and the main territories of the crown of Aragon (Catalonia, Valencia, the Balearic Islands and Aragon).[82]

- Lingua Franca or Sabir, the original of the name, an Italian and Catalan-based pidgin language of mixed origins used by maritime commercial interests around the Mediterranean in the Middle Ages and early Modern Age.[83]

- Old French in continental western European countries and in the Crusader states.[84]

- Czech, mainly during the reign of Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV (14th century) but also during other periods of Bohemian control over the Holy Roman Empire.[citation needed]

- Middle Low German, around the 14th–16th century, during the heyday of the Hanseatic League, mainly in Northeastern Europe across the Baltic Sea.

- Spanish as Castilian in Spain and New Spain from the times of the Catholic Monarchs and Columbus, c. 1492; that is, after the Reconquista, until established as a national language in the times of Louis XIV, c. 1648; subsequently multinational in all nations in or formerly in the Spanish Empire.[85]

- Polish, due to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (16th–18th centuries).[citation needed]

- Italian due to the Renaissance, the opera, the Italian Empire, the fashion industry and the influence of the Roman Catholic church.[86]

- French from the golden age under Cardinal Richelieu and Louis XIV c. 1648; i.e., after the Thirty Years' War, in France and the French colonial empire, until established as the national language during the French Revolution of 1789 and subsequently multinational in all nations in or formerly in the various French Empires.[84]

- German in Northern, Central, and Eastern Europe.[87]

- English in Great Britain until its consolidation as a national language in the Renaissance and the rise of Modern English; subsequently internationally under the various states in or formerly in the British Empire; globally since the victories of the predominantly English speaking countries (United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and others) and their allies in the two world wars ending in 1918 (World War I) and 1945 (World War II) and the subsequent rise of the United States as a superpower and major cultural influence.[citation needed]

- Russian in the former Soviet Union and Russian Empire including Northern and Central Asia.[citation needed]

Linguistic minorities

[edit]Historical attitudes towards linguistic diversity are illustrated by two French laws: the Ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts (1539), which said that every document in France should be written in French (neither in Latin nor in Occitan) and the Loi Toubon (1994), which aimed to eliminate anglicisms from official documents. States and populations within a state have often resorted to war to settle their differences. There have been attempts to prevent such hostilities: two such initiatives were promoted by the Council of Europe, founded in 1949, which affirms the right of minority language speakers to use their language fully and freely.[88] The Council of Europe is committed to protecting linguistic diversity. Currently all European countries except France, Andorra and Turkey have signed the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, while Greece, Iceland and Luxembourg have signed it, but have not ratified it; this framework entered into force in 1998. Another European treaty, the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, was adopted in 1992 under the auspices of the Council of Europe: it entered into force in 1998, and while it is legally binding for 24 countries, France, Iceland, Italy, North Macedonia, Moldova and Russia have chosen to sign without ratifying the convention.[89][90]

Scripts

[edit]

The main scripts used in Europe today are the Latin and Cyrillic.[91]

The Greek alphabet was derived from the Phoenician alphabet, and Latin was derived from the Greek via the Old Italic alphabet. In the Early Middle Ages, Ogham was used in Ireland and runes (derived from Old Italic script) in Scandinavia. Both were replaced in general use by the Latin alphabet by the Late Middle Ages. The Cyrillic script was derived from the Greek with the first texts appearing around 940 AD.[citation needed]

Around 1900 there were mainly two typeface variants of the Latin alphabet used in Europe: Antiqua and Fraktur. Fraktur was used most for German, Estonian, Latvian, Norwegian and Danish whereas Antiqua was used for Italian, Spanish, French, Polish, Portuguese, English, Romanian, Swedish and Finnish. The Fraktur variant was banned by Hitler in 1941, having been described as "Schwabacher Jewish letters".[92] Other scripts have historically been in use in Europe, including Phoenician, from which modern Latin letters descend, Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs on Egyptian artefacts traded during Antiquity, various runic systems used in Northern Europe preceding Christianisation, and Arabic during the era of the Ottoman Empire.[citation needed]

Hungarian rovás was used by the Hungarian people in the early Middle Ages, but it was gradually replaced with the Latin-based Hungarian alphabet when Hungary became a kingdom, though it was revived in the 20th century and has certain marginal, but growing area of usage since then.[93]

European Union

[edit]The European Union (as of 2021) had 27 member states accounting for a population of 447 million, or about 60% of the population of Europe.[94]

The European Union has designated by agreement with the member states 24 languages as "official and working": Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Danish, Dutch, English, Estonian, Finnish, French, German, Greek, Hungarian, Irish, Italian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Maltese, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovak, Slovenian, Spanish and Swedish.[95] This designation provides member states with two "entitlements": the member state may communicate with the EU in any of the designated languages, and view "EU regulations and other legislative documents" in that language.[96]

The European Union and the Council of Europe have been collaborating in education of member populations in languages for "the promotion of plurilingualism" among EU member states.[97] The joint document, "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR)", is an educational standard defining "the competencies necessary for communication" and related knowledge for the benefit of educators in setting up educational programs. In a 2005 independent survey requested by the EU's Directorate-General for Education and Culture regarding the extent to which major European languages were spoken in member states. The results were published in a 2006 document, "Europeans and Their Languages", or "Eurobarometer 243". In this study, statistically relevant[clarification needed][Do you mean "significant"?] samples of the population in each country were asked to fill out a survey form concerning the languages that they spoke with sufficient competency "to be able to have a conversation".[98]

List of languages

[edit]The following is a table of European languages. The number of speakers as a first or second language (L1 and L2 speakers) listed are speakers in Europe only;[nb 1] see list of languages by number of native speakers and list of languages by total number of speakers for global estimates on numbers of speakers.[citation needed]

The list is intended to include any language variety with an ISO 639 code. However, it omits sign languages. Because the ISO-639-2 and ISO-639-3 codes have different definitions, this means that some communities of speakers may be listed more than once. For instance, speakers of Bavarian are listed both under "Bavarian" (ISO-639-3 code bar) as well as under "German" (ISO-639-2 code de).[99]

| Name | ISO- 639 |

Classification | Speakers in Europe | Official status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native | Total | National[nb 2] | Regional | |||

| Abaza | abq | Northwest Caucasian, Abazgi | 49,800[100] | Karachay-Cherkessia (Russia) | ||

| Adyghe | ady | Northwest Caucasian, Circassian | 117,500[101] | Adygea (Russia) | ||

| Aghul | agx | Northeast Caucasian, Lezgic | 29,300[102] | Dagestan (Russia) | ||

| Akhvakh | akv | Northeast Caucasian, Avar–Andic | 210[103] | |||

| Albanian (Shqip) Arbëresh Arvanitika |

sq | Indo-European | 5,367,000[104] 5,877,100[105] (Balkans) |

Albania, Kosovo[nb 3], North Macedonia | Italy, Arbëresh dialect: Sicily, Calabria,[106] Apulia, Molise, Basilicata, Abruzzo, Campania Montenegro (Ulcinj, Tuzi) | |

| Andi | ani | Northeast Caucasian, Avar–Andic | 5,800[107] | |||

| Aragonese | an | Indo-European, Romance, Western, West Iberian | 25,000[108] | 55,000[109] | Northern Aragon (Spain)[nb 4] | |

| Archi | acq | Northeast Caucasian, Lezgic | 970[110] | |||

| Aromanian | rup | Indo-European, Romance, Eastern | 114,000[111] | North Macedonia (Kruševo) | ||

| Asturian (Astur-Leonese) | ast | Indo-European, Romance, Western, West Iberian | 351,791[112] | 641,502[112] | Asturias[nb 4] | |

| Avar | av | Northeast Caucasian, Avar–Andic | 760,000 | Dagestan (Russia) | ||

| Azerbaijani | az | Turkic, Oghuz | 500,000[113] | Azerbaijan | Dagestan (Russia) | |

| Bagvalal | kva | Northeast Caucasian, Avar–Andic | 1,500[114] | |||

| Bashkir | ba | Turkic, Kipchak | 1,221,000[115] | Bashkortostan (Russia) | ||

| Basque | eu | Basque | 750,000[116] | Basque Country: Basque Autonomous Community, Navarre (Spain), French Basque Country (France)[nb 4] | ||

| Bavarian | bar | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, Upper, Bavarian | 14,000,000[117] | Austria (as German) | South Tyrol | |

| Belarusian | be | Indo-European, Slavic, East | 3,300,000[118] | Belarus | ||

| Bezhta | kap | Northeast Caucasian, Tsezic | 6,800[119] | |||

| Bosnian | bs | Indo-European, Slavic, South, Western, Serbo-Croatian | 2,500,000[120] | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Kosovo[nb 3], Montenegro | |

| Botlikh | bph | Northeast Caucasian, Avar–Andic | 210[121] | |||

| Breton | br | Indo-European, Celtic, Brittonic | 206,000[122] | None, de facto status in Brittany (France) | ||

| Bulgarian | bg | Indo-European, Slavic, South, Eastern | 7,800,000[123] | Bulgaria | Mount Athos (Greece) | |

| Catalan | ca | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Occitano-Romance | 4,000,000[124] | 10,000,000[125] | Andorra | Balearic Islands (Spain), Catalonia (Spain), Valencian Community (Spain), easternmost Aragon (Spain)[nb 4], Pyrénées-Orientales (France)[nb 4], Alghero (Italy) |

| Chamalal | cji | Northeast Caucasian, Avar–Andic | 500[126] | |||

| Chechen | ce | Northeast Caucasian, Nakh | 1,400,000[127] | Chechnya & Dagestan (Russia) | ||

| Chuvash | cv | Turkic, Oghur | 1,100,000[128] | Chuvashia (Russia) | ||

| Cimbrian | cim | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, Upper, Bavarian | 400[129] | |||

| Cornish | kw | Indo-European, Celtic, Brittonic | 563[130] | Cornwall (United Kingdom)[nb 4] | ||

| Corsican | co | Indo-European, Romance, Italo-Dalmatian | 30,000[131] | 125,000[131] | Corsica (France), Sardinia (Italy) | |

| Crimean Tatar | crh | Turkic, Kipchak | 480,000[132] | Crimea (Ukraine) | ||

| Croatian | hr | Indo-European, Slavic, South, Western, Serbo-Croatian | 5,600,000[133] | Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia | Burgenland (Austria), Vojvodina (Serbia) | |

| Czech | cs | Indo-European, Slavic, West, Czech–Slovak | 10,600,000[134] | Czech Republic | ||

| Danish | da | Indo-European, Germanic, North | 5,500,000[135] | Denmark | Faroe Islands (Denmark), Schleswig-Holstein (Germany)[136] | |

| Dargwa | dar | Northeast Caucasian, Dargin | 490,000[137] | Dagestan (Russia) | ||

| Dutch | nl | Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low Franconian | 22,000,000[138] | 24,000,000[139] | Belgium, Netherlands | |

| Elfdalian | ovd | Indo-European, Germanic, North | 2000 | |||

| Emilian | egl | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Gallo-Italic | ||||

| English | en | Indo-European, Germanic, West, Anglo-Frisian, Anglic | 63,000,000[140] | 260,000,000[141] | Ireland, Malta, United Kingdom | |

| Erzya | myv | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Mordvinic | 120,000[142] | Mordovia (Russia) | ||

| Estonian | et | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Finnic | 1,165,400[143] | Estonia | ||

| Extremaduran | ext | Indo-European, Romance, Western, West Iberian | 200,000[144] | |||

| Fala | fax | Indo-European, Romance, Western, West Iberian | 11,000[145] | |||

| Faroese | fo | Indo-European, Germanic, North | 66,150[146] | Faroe Islands (Denmark) | ||

| Finnish | fi | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Finnic | 5,400,000[147] | Finland | Sweden, Norway, Republic of Karelia (Russia) | |

| Franco-Provençal (Arpitan) | frp | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Gallo-Romance | 140,000[148] | Aosta Valley (Italy) | ||

| French | fr | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Gallo-Romance, Oïl | 81,000,000[149] | 210,000,000[141] | Belgium, France, Luxembourg, Monaco, Switzerland, Jersey | Aosta Valley[150] (Italy) |

| Frisian | fry frr stq |

Indo-European, Germanic, West, Anglo-Frisian | 470,000[151] | Friesland (Netherlands), Schleswig-Holstein (Germany)[152] | ||

| Friulan | fur | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Rhaeto-Romance | 600,000[153] | Friuli (Italy) | ||

| Gagauz | gag | Turkic, Oghuz | 140,000[154] | Gagauzia (Moldova) | ||

| Galician | gl | Indo-European, Romance, Western, West Iberian | 2,400,000[155] | Galicia (Spain), Eo-Navia (Asturias)[nb 4], Bierzo (Province of León)[nb 4] and Western Sanabria (Province of Zamora)[nb 4] | ||

| German | de | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German | 97,000,000[156] | 170,000,000[141] | Austria, Belgium, Germany, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Switzerland | South Tyrol,[157] Friuli-Venezia Giulia[158] (Italy) |

| Godoberi | gin | Northeast Caucasian, Avar–Andic | 130[159] | |||

| Greek | el | Indo-European, Hellenic | 13,500,000[160] | Cyprus, Greece | Albania (Finiq, Dropull) | |

| Hinuq | gin | Northeast Caucasian, Tsezic | 350[161] | |||

| Hungarian | hu | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Ugric | 13,000,000[162] | Hungary | Burgenland (Austria), Vojvodina (Serbia), Romania, Slovakia, Subcarpathia (Ukraine), Prekmurje, (Slovenia) | |

| Hunzib | bph | Northeast Caucasian, Tsezic | 1,400[163] | |||

| Icelandic | is | Indo-European, Germanic, North | 330,000[164] | Iceland | ||

| Ingrian | izh | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Finnic | 120[165] | |||

| Ingush | inh | Northeast Caucasian, Nakh | 300,000[166] | Ingushetia (Russia) | ||

| Irish | ga | Indo-European, Celtic, Goidelic | 240,000[167] | 2,000,000 | Ireland | Northern Ireland (United Kingdom) |

| Istriot | ist | Indo-European, Romance | 900[168] | |||

| Istro-Romanian | ruo | Indo-European, Romance, Eastern | 1,100[169] | |||

| Italian | it | Indo-European, Romance, Italo-Dalmatian | 65,000,000[170] | 82,000,000[141] | Italy, San Marino, Switzerland, Vatican City | Istria County (Croatia), Slovenian Istria (Slovenia) |

| Judeo-Italian | itk | Indo-European, Romance, Italo-Dalmatian | 250[171] | |||

| Judaeo-Spanish (Ladino) | lad | Indo-European, Romance, Western, West Iberian | 320,000[172] | few[173] | Bosnia and Herzegovina[nb 4], France[nb 4] | |

| Kabardian | kbd | Northwest Caucasian, Circassian | 530,000[174] | Kabardino-Balkaria & Karachay-Cherkessia (Russia) | ||

| Kaitag | xdq | Northeast Caucasian, Dargin | 30,000[175] | |||

| Kalmyk | xal | Mongolic | 80,500[176] | Kalmykia (Russia) | ||

| Karata | kpt | Northeast Caucasian, Avar–Andic | 260[177] | |||

| Karelian | krl | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Finnic | 36,000[178] | Republic of Karelia (Russia) | ||

| Karachay-Balkar | krc | Turkic, Kipchak | 300,000[179] | Kabardino-Balkaria & Karachay-Cherkessia (Russia) | ||

| Kashubian | csb | Indo-European, Slavic, West, Lechitic | 50,000[180] | Poland | ||

| Kazakh | kk | Turkic, Kipchak | 1,000,000[181] | Kazakhstan | Astrakhan Oblast (Russia) | |

| Khwarshi | khv | Northeast Caucasian, Tsezic | 1,700[182] | |||

| Komi | kv | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Permic | 220,000[183] | Komi Republic (Russia) | ||

| Kubachi | ugh | Northeast Caucasian, Dargin | 7,000[184] | |||

| Kumyk | kum | Turkic, Kipchak | 450,000[185] | Dagestan (Russia) | ||

| Kven | fkv | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Finnic | 2,000-10,000[186] | Norway | ||

| Lak | lbe | Northeast Caucasian, Lak | 152,050[187] | Dagestan (Russia) | ||

| Latin | la | Indo-European, Italic, Latino-Faliscan | extinct | few[188] | Vatican City | |

| Latvian | lv | Indo-European, Baltic | 1,750,000[189] | Latvia | ||

| Lezgin | lez | Northeast Caucasian, Lezgic | 397,000[190] | Dagestan (Russia) | ||

| Ligurian | lij | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Gallo-Italic | 500,000[191] | Monaco (Monégasque dialect is the "national language") | Liguria (Italy), Carloforte and Calasetta (Sardinia, Italy)[192][193] | |

| Limburgish | li lim |

Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low Franconian | 1,300,000 (2001)[194] | Limburg (Belgium), Limburg (Netherlands) | ||

| Lithuanian | lt | Indo-European, Baltic | 3,000,000[195] | Lithuania | ||

| Livonian | liv | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Finnic | 1[196] | 210[197] | Latvia[nb 4] | |

| Lombard | lmo | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Gallo-Italic | 3,600,000[198] | Lombardy (Italy) | ||

| Low German (Low Saxon) | nds wep |

Indo-European, Germanic, West | 1,000,000[199] | 2,600,000[199] | Schleswig-Holstein (Germany)[200] | |

| Ludic | lud | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Finnic | 300[201] | |||

| Luxembourgish | lb | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German | 336,000[202] | 386,000[202] | Luxembourg | Wallonia (Belgium) |

| Macedonian | mk | Indo-European, Slavic, South, Eastern | 1,400,000[203] | North Macedonia | ||

| Mainfränkisch | vmf | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, Upper | 4,900,000[204] | |||

| Maltese | mt | Semitic, Arabic | 520,000[205] | Malta | ||

| Manx | gv | Indo-European, Celtic, Goidelic | 230[206] | 2,300[207] | Isle of Man | |

| Mari | chm mhr mrj |

Uralic, Finno-Ugric | 500,000[208] | Mari El (Russia) | ||

| Meänkieli | fit | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Finnic | 40,000[209] | 55,000[209] | Sweden | |

| Megleno-Romanian | ruq | Indo-European, Romance, Eastern | 3,000[210] | |||

| Minderico | drc | Indo-European, Romance, Western, West Iberian | 500[211] | |||

| Mirandese | mwl | Indo-European, Romance, Western, West Iberian | 15,000[212] | Miranda do Douro (Portugal) | ||

| Moksha | mdf | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Mordvinic | 2,000[213] | Mordovia (Russia) | ||

| Montenegrin | cnr | Indo-European, Slavic, South, Western, Serbo-Croatian | 240,700[214] | Montenegro | ||

| Neapolitan | nap | Indo-European, Romance, Italo-Dalmatian | 5,700,000[215] | Campania (Italy)[216] | ||

| Nenets | yrk | Uralic, Samoyedic | 4,000[217] | Nenets Autonomous Okrug (Russia) | ||

| Nogai | nog | Turkic, Kipchak | 87,000[218] | Dagestan (Russia) | ||

| Norman | nrf | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Gallo-Romance, Oïl | 50,000[219] | Guernsey (United Kingdom), Jersey (United Kingdom) | ||

| Norwegian | no | Indo-European, Germanic, North | 5,200,000[220] | Norway | ||

| Occitan | oc | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Occitano-Romance | 500,000[221] | Catalonia (Spain)[nb 5] | ||

| Ossetian | os | Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Iranian, Eastern | 450,000[222] | North Ossetia-Alania (Russia), South Ossetia | ||

| Palatinate German | pfl | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, Central | 1,000,000[223] | |||

| Picard | pcd | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Gallo-Romance, Oïl | 200,000[224] | Wallonia (Belgium) | ||

| Piedmontese | pms | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Gallo-Italic | 1,600,000[225] | Piedmont (Italy)[226] | ||

| Polish | pl | Indo-European, Slavic, West, Lechitic | 38,500,000[227] | Poland | ||

| Portuguese | pt | Indo-European, Romance, Western, West Iberian | 10,000,000[228] | Portugal | ||

| Rhaeto-Romance | fur lld roh |

Indo-European, Romance, Western | 370,000[229] | Switzerland | Veneto Belluno, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, South Tyrol,[230] & Trentino (Italy) | |

| Ripuarian (Platt) | ksh | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, Central | 900,000[231] | |||

| Romagnol | rgn | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Gallo-Italic | ||||

| Romani | rom | Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Indo-Aryan, Western | 1,500,000[232] | Kosovo[nb 3][233] | ||

| Romanian | ro | Indo-European, Romance, Eastern | 24,000,000[234] | 28,000,000[235] | Moldova, Romania | Mount Athos (Greece), Vojvodina (Serbia) |

| Russian | ru | Indo-European, Slavic, East | 106,000,000[236] | 160,000,000[236] | Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia | Mount Athos (Greece), Gagauzia (Moldova), Left Bank of the Dniester (Moldova), Ukraine |

| Rusyn | rue | Indo-European, Slavic, East | 70,000[237] | |||

| Rutul | rut | Northeast Caucasian, Lezgic | 36,400[238] | Dagestan (Russia) | ||

| Sami | se | Uralic, Finno-Ugric | 23,000[239] | Norway | Sweden, Finland | |

| Sardinian | sc | Indo-European, Romance | 1,350,000[240] | Sardinia (Italy) | ||

| Scots | sco | Indo-European, Germanic, West, Anglo-Frisian, Anglic | 110,000[241] | Scotland (United Kingdom), County Donegal (Republic of Ireland), Northern Ireland (United Kingdom) | ||

| Scottish Gaelic | gd | Indo-European, Celtic, Goidelic | 57,000[242] | Scotland (United Kingdom) | ||

| Serbian | sr | Indo-European, Slavic, South, Western, Serbo-Croatian | 9,000,000[243] | Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo[nb 3], Serbia | Croatia, Mount Athos (Greece), North Macedonia, Montenegro | |

| Sicilian | scn | Indo-European, Romance, Italo-Dalmatian | 4,700,000[244] | Sicily (Italy) | ||

| Silesian | szl | Indo-European, Slavic, West, Lechitic | 522,000[245] | |||

| Silesian German | sli | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, Central | 11,000[246] | |||

| Slovak | sk | Indo-European, Slavic, West, Czech–Slovak | 5,200,000[247] | Slovakia | Vojvodina (Serbia), Czech Republic | |

| Slovene | sl | Indo-European, Slavic, South, Western | 2,100,000[248] | Slovenia | Friuli-Venezia Giulia[158] (Italy), Austria (Carinthia, Styria) | |

| Sorbian (Wendish) | wen | Indo-European, Slavic, West | 20,000[249] | Brandenburg & Sachsen (Germany)[250] | ||

| Spanish | es | Indo-European, Romance, Western, West Iberian | 47,000,000[251] | 76,000,000[141] | Spain | Gibraltar (United Kingdom) |

| Swabian German | swg | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, Upper, Alemannic | 820,000[252] | |||

| Swedish | sv | Indo-European, Germanic, North | 11,100,000[253] | 13,280,000[253] | Sweden, Finland, Åland and Estonia | |

| Swiss German | gsw | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, Upper, Alemannic | 5,000,000[254] | Switzerland (as German) | ||

| Tabasaran | tab | Northeast Caucasian, Lezgic | 126,900[255] | Dagestan (Russia) | ||

| Tat | ttt | Indo-European, Iranian, Western | 30,000[256] | Dagestan (Russia) | ||

| Tatar | tt | Turkic, Kipchak | 4,300,000[257] | Tatarstan (Russia) | ||

| Tindi | tin | Northeast Caucasian, Avar–Andic | 2,200[258] | |||

| Tsez | ddo | Northeast Caucasian, Tsezic | 13,000[259] | |||

| Turkish | tr | Turkic, Oghuz | 15,752,673[260] | Turkey, Cyprus | Northern Cyprus | |

| Udmurt | udm | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Permic | 340,000[261] | Udmurtia (Russia) | ||

| Ukrainian | uk | Indo-European, Slavic, East | 32,600,000[262] | Ukraine | Left Bank of the Dniester (Moldova) | |

| Upper Saxon | sxu | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, Central | 2,000,000[263] | |||

| Vepsian | vep | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Finnic | 1,640[264] | Republic of Karelia (Russia) | ||

| Venetian | vec | Indo-European, Romance, Italo-Dalmatian | 3,800,000[265] | Veneto (Italy)[266] | ||

| Võro | vro | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Finnic | 87,000[267] | Võru County (Estonia) | ||

| Votic | vot | Uralic, Finno-Ugric, Finnic | 21[268] | |||

| Walloon | wa | Indo-European, Romance, Western, Gallo-Romance, Oïl | 600,000[269] | Wallonia (Belgium) | ||

| Walser German | wae | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German, Upper, Alemannic | 20,000[270] | |||

| Welsh | cy | Indo-European, Celtic, Brittonic | 562,000[271] | 750,000 | Wales (United Kingdom) | |

| Wymysorys | wym | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German | 70[272] | |||

| Yenish | yec | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German | 16,000[273] | Switzerland[nb 4] | ||

| Yiddish | yi | Indo-European, Germanic, West, High German | 600,000[274] | Bosnia and Herzegovina[nb 4], Netherlands[nb 4], Poland[nb 4], Romania[nb 4], Sweden[nb 4], Ukraine[nb 4] | ||

| Zeelandic | zea | Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low Franconian | 220,000[275] | |||

Languages spoken in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cyprus, Georgia, and Turkey

[edit]There are various definitions of Europe, which may or may not include all or parts of Turkey, Cyprus, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. For convenience, the languages and associated statistics for all five of these countries are grouped together on this page, as they are usually presented at a national, rather than subnational, level.

| Name | ISO- 639 |

Classification | Speakers in expanded geopolitical Europe | Official status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | L1+L2 | National[nb 6] | Regional | |||

| Abkhaz | ab | Northwest Caucasian, Abazgi | Abkhazia/Georgia:[276] 191,000[277] Turkey: 44,000[278] |

Abkhazia | Abkhazia | |

| Adyghe (West Circassian) | ady | Northwest Caucasian, Circassian | Turkey: 316,000[278] | |||

| Albanian | sq | Indo-European, Albanian | Turkey: 66,000 (Tosk)[278] | |||

| Arabic | ar | Afro-Asiatic, Semitic, West | Turkey: 2,437,000 Not counting post-2014 Syrian refugees[278] | |||

| Armenian | hy | Indo-European, Armenian | Armenia: 3 million[279] Azerbaijan: 145,000 [citation needed] Georgia: around 0.2 million ethnic Armenians (Abkhazia: 44,870[280]) Turkey: 61,000[278] Cyprus: 668[281]: 3 |

Armenia Azerbaijan |

Cyprus | |

| Azerbaijani | az | Turkic, Oghuz | Azerbaijan 9 million[citation needed][282] Turkey: 540,000[278] Georgia 0.2 million |

Azerbaijan | ||

| Batsbi | bbl | Northeast Caucasian, Nakh | Georgia: 500[283][needs update] | |||

| Bulgarian | bg | Indo-European, Slavic, South | Turkey: 351,000[278] | |||

| Crimean Tatar | crh | Turkic, Kipchak | Turkey: 100,000[278] | |||

| Georgian | ka | Kartvelian, Karto-Zan | Georgia: 3,224,696[284] Turkey: 151,000[278] Azerbaijan: 9,192 ethnic Georgians[285] |

Georgia | ||

| Greek | el | Indo-European, Hellenic | Cyprus: 679,883[286]: 2.2 Turkey: 3,600[278] |

Cyprus | ||

| Juhuri | jdt | Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Iranian, Southwest | Azerbaijan: 24,000 (1989)[287][needs update] | |||

| Kurdish | kur | Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Iranian, Northwest | Turkey: 15 million[288] Azerbaijan: 9,000[citation needed] |

|||

| Kurmanji | kmr | Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Iranian, Northwest | Turkey: 8.13 million[289] Armenia: 33,509[290] Georgia: 14,000 [citation needed] |

Armenia | ||

| Laz | lzz | Kartvelian, Karto-Zan, Zan | Turkey: 20,000[291] Georgia: 2,000[291] |

|||

| Megleno-Romanian | ruq | Indo-European, Italic, Romance, East | Turkey: 4–5,000[292] | |||

| Mingrelian | xmf | Kartvelian, Karto-Zan, Zan | Georgia (including Abkhazia): 344,000[293] | |||

| Pontic Greek | pnt | Indo-European, Hellenic | Turkey: greater than 5,000[294] Armenia: 900 ethnic Caucasus Greeks[295] Georgia: 5,689 Caucasus Greeks[284] |

|||

| Romani language and Domari language | rom, dmt | Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Indic | Turkey: 500,000[278] | |||

| Russian | ru | Indo-European, Balto-Slavic, Slavic | Armenia: 15,000[296] Azerbaijan: 250,000[296] Georgia: 130,000[296] |

Armenia: about 0.9 million[297] Azerbaijan: about 2.6 million[297] Georgia: about 1 million[297] Cyprus: 20,984[298] |

Abkhazia South Ossetia |

Armenia Azerbaijan |

| Svan | sva | Kartvelian, Svan | Georgia (incl. Abkhazia): 30,000[299] | |||

| Tat | ttt | Indo-European, Indo-Aryan, Iranian, Southwest | Azerbaijan: 10,000[300][needs update] | |||

| Turkish | tr | Turkic, Oghuz | Turkey: 66,850,000[278] Cyprus: 1,405[301] + 265,100 in the North[302] |

Turkey Cyprus Northern Cyprus |

||

| Zazaki | zza | Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Iranian, Northwest | Turkey: 3–4 million (2009)[303][304] | |||

Immigrant communities

[edit]Recent (post–1945) immigration to Europe introduced substantial communities of speakers of non-European languages.[3]

The largest such communities include Arabic speakers (see Arabs in Europe) and Turkish speakers (beyond European Turkey and the historical sphere of influence of the Ottoman Empire, see Turks in Europe).[305] Armenians, Berbers, and Kurds have diaspora communities of c. 1–2,000,000 each. The various languages of Africa and languages of India form numerous smaller diaspora communities.

- List of the largest immigrant languages

| Name | ISO 639 | Classification | Native | Ethnic diaspora |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabic | ar | Afro-Asiatic, Semitic | 5,000,000[306] | Unknown |

| Turkish | tr | Turkic, Oghuz | 3,000,000[307] | 7,000,000[308] |

| Armenian | hy | Indo-European | 1,000,000[309] | 3,000,000[310] |

| Bengali | bn | Indo-European, Indo-Aryan | 600,000[311] | 1,000,000[312] |

| Kurdish | ku | Indo-European, Iranian, Western | 600,000[313] | 1,000,000[314] |

| Azerbaijani | az | Turkic, Oghuz | 500,000[315] | 700,000[316] |

| Kabyle | kab | Afro-Asiatic, Berber | 500,000[317] | 1,000,000[318] |

| Chinese | zh | Sino-Tibetan, Sinitic | 300,000[319] | 2,000,000[320] |

| Urdu | ur | Indo-European, Indo-Aryan | 300,000[321] | 1,800,000[322] |

| Uzbek | uz | Turkic, Karluk | 300,000[323] | 2,000,000[324] |

| Persian | fa | Indo-European, Iranian, Western | 300,000[325] | 400,000[326] |

| Punjabi | pa | Indo-European, Indo-Aryan | 300,000[327] | 700,000[328] |

| Gujarati | gu | Indo-European, Indo-Aryan | 200,000[329] | 600,000[330] |

| Tamil | ta | Dravidian | 200,000[331] | 500,000[332] |

| Somali | so | Afro-Asiatic, Cushitic | 200,000[333] | 400,000[334] |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Europe" is taken as a geographical term, defined by the conventional Europe-Asia boundary along the Caucasus and the Urals. Estimates for populations geographically in Europe are given for transcontinental countries.

- ^ Sovereign states, defined as United Nations member states and observer states. 'Recognised minority language' status is not included.

- ^ a b c d The Republic of Kosovo is a partially recognized state (recognized by 111 out of 193 UN member states as of 2017).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Recognized and protected, but not official.

- ^ The Aranese dialect, in Val d'Aran county.

- ^ Sovereign states, defined as United Nations member states and observer states. 'Recognised minority language' status is not included.

References

[edit]- ^ "Ethnologue: Statistics". Ethnologue (26 ed.). Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b "European Day of Languages > Facts > Language Facts". edl.ecml.at. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b "International migrant stock: By destination and origin". United Nations.

- ^ Emery, Chad (15 December 2022). "34 of the Most Spoken Languages in Europe: Key Facts and Figures". Langoly. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ König, Ekkehard; van der Auwera, Johan (1994). The Germanic languages. London: Routledge.

- ^ Sipka, Danko (2022). "The Geography of Words" (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ Versloot, Arjen; Adamczyk, Elzbieta (1 January 2017). "The Geography and Dialects of Old Saxon: River-basin communication networks and the distributional patterns of North Sea Germanic features in Old Saxon". Frisians and Their North Sea Neighbours: 125. doi:10.1515/9781787440630-014.

- ^ "The Evolution of English: Contribution of European Languages". www.98thpercentile.com. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "Scots language | History, Examples, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 5 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b Kuipers-Zandberg, Helga; Kircher, Ruth (1 November 2020). "The Objective and Subjective Ethnolinguistic Vitality of West Frisian: Promotion and Perception of a Minority Language in the Netherlands". Sustainable Multilingualism. 17 (1): 1–25. doi:10.2478/sm-2020-0011. S2CID 227129146.

- ^ Winter, Christoph (21 December 2022), "Frisian", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.938, ISBN 978-0-19-938465-5, retrieved 21 May 2023

- ^ "Dutch language | Definition, Origin, History, Countries, Examples, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 15 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "German, Standard | Ethnologue Free". Ethnologue (Free All). Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Origins of Yiddish". sites.santafe.edu. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "All You Need To Know About The Official Languages Of Germany". gtelocalize.com. 28 December 2023. Retrieved 13 January 2025.

- ^ Russ, Charles (13 September 2013). The Dialects of Modern German. doi:10.4324/9781315001777. ISBN 9781315001777.

- ^ Louden, Mark L. (2020). "Minority Germanic Languages". The Cambridge Handbook of Germanic Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 807–832. doi:10.1017/9781108378291.035. ISBN 978-1-108-42186-7.

- ^ "Linguist makes sensational claim: English is a Scandinavian language". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- ^ "Linguistic variety in the Nordics". nordics.info. 21 February 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Gooskens, Charlotte; Kürschner, Sebastian; Heuven, Vincent J. van (4 August 2021). "The role of loanwords in the intelligibility of written Danish among Swedes". Nordic Journal of Linguistics. 45 (1): 4–29. doi:10.1017/S0332586521000111. hdl:1887/3205273. ISSN 0332-5865.

- ^ Gooskens, Charlotte; van Heuven, Vincent J.; Golubović, Jelena; Schüppert, Anja; Swarte, Femke; Voigt, Stefanie (3 April 2018). "Mutual intelligibility between closely related languages in Europe". International Journal of Multilingualism. 15 (2): 169–193. doi:10.1080/14790718.2017.1350185. hdl:1887/79190. ISSN 1479-0718.

- ^ Ti Alkire; Carol Rosen (2010). Romance languages: a Historical Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 3.

- ^ Sergio Lubello (2016). Manuale Di Linguistica Italiana, Manuals of Romance linguistics. De Gruyter. p. 499.

- ^ This includes all of the varieties of Sardinian, written with any orthography (the LSC, used for all of Sardinian, or the Logudorese, Nugorese and Campidanese orthographies, only used for some dialects of it) but does not include Gallurese and Sassarese, that even though they have sometimes been included in a supposed Sardinian "macro-language" are actually considered by all Sardinian linguists two different transitional languages between Sardinian and Corsican (or, in the case of Gallurese, are sometimes classified as a variant of Corsican). For Gallurese: ATTI DEL II CONVEGNO INTERNAZIONALE DI STUDI Ciurrata di la Linga Gadduresa, 2014, for Sassarese: Maxia, Mauro (2010). Studi sardo-corsi. Dialettologia e storia della lingua tra le due isole (in Italian). Sassari: Taphros. p. 58.

La tesi che individua nel sassarese una base essenzialmente toscana deve essere riesaminata alla luce delle cospicue migrazioni corse che fin dall'età giudicale interessarono soprattutto il nord della Sardegna. In effetti, che il settentrione della Sardegna, almeno dalla metà del Quattrocento, fosse interessato da un forte presenza corsa si può desumere da diversi punti di osservazione. Una delle prove più evidenti è costituita dall'espressa citazione che di questo fenomeno fa il cap. 42 del secondo libro degli Statuti del comune di Sassari, il quale fu aggiunto nel 1435 o subito dopo. Se si tiene conto di questa massiccia presenza corsa e del fatto che la presenza pisana nel regno di Logudoro cessò definitivamente entro il Duecento, l'origine del fondo toscano non andrà attribuita a un influsso diretto del pisano antico ma del corso che rappresenta, esso stesso, una conseguenza dell'antica toscanizzazione della Corsica

). They are legally considered two different languages by the Sardinian Regional Government too (Autonomous Region of Sardinia (15 October 1997). "Legge Regionale 15 ottobre 1997, n. 26" (in Italian). pp. Art. 2, paragraph 4. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2008.). - ^ "Romance languages | Definition, Origin, Characteristics, Classification, Map, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 6 February 2025. Retrieved 27 February 2025.

- ^ Friedman, Lawrence; Perez-Perdomo, Rogelio (2003). Legal Culture in the Age of Globalization: Latin America and Latin Europe. Stanford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-8047-6695-9.

- ^ "Slavic languages | List, Definition, Origin, Map, Tree, History, & Number of Speakers | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 2 November 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Polish at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ Ukrainian at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ Serbo-Croatian at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ Czech at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ Bulgarian at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ Slovak at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ Belarusian at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ Slovene at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ "Macedonian Language". Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 12 January 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "Slavic | Ethnologue Free". Ethnologue (Free All). Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ F. Violi, Lessico Grecanico-Italiano-Grecanico, Apodiafàzzi, Reggio Calabria, 1997.

- ^ Paolo Martino, L'isola grecanica dell'Aspromonte. Aspetti sociolinguistici, 1980. Risultati di un'inchiesta del 1977

- ^ Filippo Violi, Storia degli studi e della letteratura popolare grecanica, C.S.E. Bova (RC), 1992

- ^ Filippo Condemi, Grammatica Grecanica, Coop. Contezza, Reggio Calabria, 1987;

- ^ "In Salento e Calabria le voci della minoranza linguistica greca". Treccani, l'Enciclopedia italiana.

- ^ Gerhard Rohlfs; Salvatore Sicuro. "Grammatica storica dei dialetti italogreci". (No Title) (in Italian). Archived from the original on 20 April 2024. Retrieved 8 June 2024.

- ^ Dansby, Angela (16 December 2020). "The last speakers of ancient Sparta". BBC Home. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Pronk, Tijmen (2017). USQUE AD RADICES Indo-European studies in honour of Birgit Anette Olsen: Curonian accentuation. Copenhagen, Denmark: Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 659. ISBN 9788763545761.

- ^ Vaba, Lembit (July 2014). "Curonian linguistic elements in Livonian". Eesti ja Soome-Ugri Keeleteaduse Ajakiri. 5 (1): 173–191. doi:10.12697/jeful.2014.5.1.09. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ Nomachi, Motoki (2019). "Placing Kashubian in the Circum-Baltic (CB) area". Prace Filologiczne. LXXIV (2019): 315–328. doi:10.32798/pf.470. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ Mažiulis, Vytautas J. (26 July 1999). "Baltic Languages". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ Szatkowski, Piotr (January 2022). "Language Practices in a Family of Prussian Language Revivalists: Conclusions Based on Short-Term Participant Observation". Adeptus (2626): 173. doi:10.11649/a.2626. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ Çerpja, Adelina; Çepani, Anila (December 2023). "Albanian Dialect Classifications" (PDF). Dialectologia. 11 (2023): 51–87. doi:10.1344/dialectologia2023.2023.3. Retrieved 8 March 2025.

- ^ "Data am y Gymraeg o'r Arolwg Blynyddol o'r Boblogaeth: 2024". Llywodraeth Cymru (Free All) (in Welsh). Retrieved 14 June 2025.

- ^ "Cornish | Ethnologue Free". Ethnologue (Free All). Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Breton | Ethnologue Free". Ethnologue (Free All). Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Irish | Ethnologue Free". Ethnologue (Free All). Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Scottish Gaelic | Ethnologue Free". Ethnologue (Free All). Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Manx | Ethnologue Free". Ethnologue (Free All). Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic". www.asnc.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Celtic languages | History, Features, Origin, Map, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 22 December 2023. Retrieved 23 December 2023.

- ^ a b Zatreanu M, Halwachs DW, ROMANI IN EUROPE (PDF), The Council of Europe

- ^ Thordarson, Fridrik (1 January 2000). "CAUCASUS ii. Language contact". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 22 June 2025.

- ^ "Uralic languages | Finno-Ugric, Samoyedic, & Permic Groups | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 24 February 2025. Retrieved 25 March 2025.

- ^ Alexander, Marie; et al. (2009). "2nd International Conference of Maltese Linguistics: Saturday, September 19 – Monday, September 21, 2009". International Association of Maltese Linguistics. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- ^ Aquilina, J. (1958). "Maltese as a Mixed Language". Journal of Semitic Studies. 3 (1): 58–79. doi:10.1093/jss/3.1.58.

- ^ Aquilina, Joseph (July–September 1960). "The Structure of Maltese". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 80 (3): 267–68. doi:10.2307/596187. JSTOR 596187.

- ^ Werner, Louis; Calleja, Alan (November–December 2004). "Europe's New Arabic Connection". Saudi Aramco World. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- ^ "Assyrian Neo-Aramaic | Ethnologue Free". Ethnologue (Free All). Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ a b "Turkic languages | Geography, History, & Comparison | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 28 February 2025. Retrieved 25 March 2025.

- ^ Yükselen Peler, Gökçe (2018). "Tarih İçinde Yunanistan'da Türk Dili: Hun-Avar-Bulgar Dönemi". Journal of Turkish Language and Literature. 58 (2): 429–448. doi:10.26650/TUDED2018-0004.

- ^ Gudava, T. E. "North Caucasian languages". Britannica. Retrieved 14 June 2025.

- ^ "Kalmyk". Center for Language Technology. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ "Kartvelian languages | Kartvelian, Georgian, Svan & Laz". Britannica. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ "La Langue des signes française (LSF) | Fondation pour l'audition". www.fondationpourlaudition.org. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ Reagan, Timothy (2014). "Language Policy for Sign Languages". The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. pp. 1–6. doi:10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal1417. ISBN 9781405194730.

- ^ Murray, Joseph J. (2015). "Linguistic Human Rights Discourse in Deaf Community Activism". Sign Language Studies. 15 (4): 379–410. doi:10.1353/sls.2015.0012. JSTOR 26190995. PMC 4490244. PMID 26190995.

- ^ Reagan, Timothy (2021). "Historical Linguistics and the Case for Sign Language Families". Sign Language Studies. 21 (4): 427–454. doi:10.1353/sls.2021.0006. ISSN 1533-6263. S2CID 236778280.

- ^ Power, Justin M. (2022). "Historical Linguistics of Sign Languages: Progress and Problems". Frontiers in Psychology. 13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.818753. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 8959496. PMID 35356353.

- ^ Andrews, Bruce. "The rich diversity of sign languages explained". news.csu.edu.au. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "BANZSL". www.signcommunity.org.uk. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "Chapter 2. The Linguistic Setup of Sign Languages – The Case of Irish Sign Language (ISL)", Mouth Actions in Sign Languages (in German), De Gruyter Mouton, 28 July 2014, pp. 4–30, doi:10.1515/9781614514978.4, ISBN 978-1-61451-497-8

- ^ Mark, Joshua (28 June 2019). "Religion in the Middle Ages". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15 December 2023.

- ^ Counelis, James Steve (March 1976). "Review [untitled] of Ariadna Camariano-Cioran, Les Academies Princieres de Bucarest et de Jassy et leur Professeurs". Church History. 45 (1): 115–116. doi:10.2307/3164593. JSTOR 3164593. S2CID 162293323.

...Greek, the lingua franca of commerce and religion, provided a cultural unity to the Balkans...Greek penetrated Moldavian and Wallachian territories as early as the fourteenth century.... The heavy influence of Greek culture upon the intellectual and academic life of Bucharest and Jassy was longer termed than historians once believed.

- ^ "A troubadour literary koiné?".

- ^ Wansbrough, John E. (1996). "Chapter 3: Lingua Franca". Lingua Franca in the Mediterranean. Routledge.

- ^ a b Calvet, Louis Jean (1998). Language wars and linguistic politics. Oxford [England]; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 175–76.

- ^ Jones, Branwen Gruffydd (2006). Decolonizing international relations. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 98.

- ^ Kahane, Henry (September 1986). "A Typology of the Prestige Language". Language. 62 (3): 495–508. doi:10.2307/415474. JSTOR 415474.

- ^ Darquennes, Jeroen; Nelde, Peter (2006). "German as a Lingua Franca". Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. 26: 61–77. doi:10.1017/s0267190506000043. S2CID 61449212.

- ^ "European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages: Strasbourg, 5.XI.1992". Council of Europe. 1992. Archived from the original on 26 February 2011. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- ^ Protsyk, Oleh; Harzl, Benedikt (7 May 2013). Managing Ethnic Diversity in Russia. Routledge. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-136-26774-1.

- ^ Assembly, Council of Europe: Parliamentary (8 November 2006). Documents: working papers, 2006 ordinary session (first part), 23 -27 January 2006, Vol. 1: Documents 10711, 10712, 10715-10769. Council of Europe. p. 235. ISBN 978-92-871-5932-8.

- ^ Dimitrov, Bogoya (19 May 2023). "Book Exhibition Dedicated to the Day of the Cyrillic Alphabet". The EUI Library Blog. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Facsimile of Bormann's Memorandum (in German)

The memorandum itself is typed in Antiqua, but the NSDAP letterhead is printed in Fraktur.

"For general attention, on behalf of the Führer, I make the following announcement:

It is wrong to regard or to describe the so‑called Gothic script as a German script. In reality, the so‑called Gothic script consists of Schwabach Jew letters. Just as they later took control of the newspapers, upon the introduction of printing the Jews residing in Germany took control of the printing presses and thus in Germany the Schwabach Jew letters were forcefully introduced.

Today the Führer, talking with Herr Reichsleiter Amann and Herr Book Publisher Adolf Müller, has decided that in the future the Antiqua script is to be described as normal script. All printed materials are to be gradually converted to this normal script. As soon as is feasible in terms of textbooks, only the normal script will be taught in village and state schools.

The use of the Schwabach Jew letters by officials will in future cease; appointment certifications for functionaries, street signs, and so forth will in future be produced only in normal script.

On behalf of the Führer, Herr Reichsleiter Amann will in future convert those newspapers and periodicals that already have foreign distribution, or whose foreign distribution is desired, to normal script". - ^ Gleichgewicht, Daniel (30 April 2020). "New illiberalism and the old Hungarian alphabet". New Eastern Europe. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Population on 1 January". Eurostat. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ "Languages Policy: Linguistic diversity: Official languages of the EU". European Commission, European Union. 4 June 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ^ "Languages of Europe: Official EU languages". European Commission, European Union. 2009. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ "Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR)". Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 30 October 2009. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ "Europeans and Their Languages" (PDF). European Commission. 2006. p. 8. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- ^ "Relationships to other parts of ISO 639 | ISO 639-3". iso639-3.sil.org. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ Abaza at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Adyghe at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Aghul at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Akhvakh at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Albanian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ "Albanian". Ethnologue. Retrieved 12 December 2018. Population total of all languages of the Albanian macrolanguage.

- ^ "Norme per la tutela e la valorizzazione della lingua e del patrimonio culturale delle minoranze linguistiche e storiche di Calabria". Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ Andi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ https://zaguan.unizar.es/record/60448 Report about Census of population 2011 of Aragonese Sociolinguistics Seminar and University of Zaragoza

- ^ "Más de 50.000 personas hablan aragonés". Aragón Digital. Archived from the original on 1 January 2015.

- ^ Archi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Aromanian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ a b III Sociolinguistic Study of Asturias (2017). Euskobarometro.

- ^ c. 130,000 in Dagestan. In addition, there are about 0.5 million speakers in immigrant communities in Russia, see #Immigrant communities. Azerbaijani at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Bagvalal at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Bashkort at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ (in French) VI° Enquête Sociolinguistique en Euskal herria (Communauté Autonome d'Euskadi, Navarre et Pays Basque Nord) Archived 21 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine (2016).

- ^ German dialect, Bavarian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Belarusian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Bezhta at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Bosnian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Botlikh at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Breton at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Bulgarian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ "Catalan". 19 November 2019.

- ^ "Informe sobre la Situació de la Llengua Catalana | Xarxa CRUSCAT. Coneixements, usos i representacions del català". blogs.iec.cat.

- ^ Chamalal at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Chechen at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Chuvash at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ German dialect, Cimbrian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ "Main language (detailed)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 31 July 2023. (UK 2021 Census)

- ^ a b Corsican at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Crimean Tatar at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Croatian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Czech at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Danish at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ recognized as official language in Nordfriesland, Schleswig-Flensburg, Flensburg and Rendsburg-Eckernförde (§ 82b LVwG Archived 3 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Dargwa at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Dutch at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ "Feiten en cijfers - Wat iedereen zou moeten weten over het Nederlands" (in Dutch). Rijksoverheid. 11 January 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ^ English at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e Europeans and their Languages Archived 6 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Data for EU27 Archived 29 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine, published in 2012.

- ^ Erzya at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Estonian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Extremaduran at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Fala at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Faroese at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Finnish at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Franco-Provençal at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ French at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Le Statut spécial de la Vallée d'Aoste, Article 38, Title VI. Region Vallée d'Aoste. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ Frisian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ recognized as official language in the Nordfriesland district and in Helgoland (§ 82b LVwG Archived 3 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ e18|fur|Friulan

- ^ Gagauz at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Galician at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ includes: bar Bavarian, cim Cimbrian, ksh Kölsch, sli Lower Silesian, vmf Mainfränkisch, pfl Palatinate German, swg Swabian German, gsw Swiss German, sxu Upper Saxon, wae Walser German, wep Westphalian, wym Wymysorys, yec Yenish, yid Yiddish; see German dialects.

- ^ Statuto Speciale Per Il Trentino-Alto Adige Archived 26 November 2018 at the Wayback Machine (1972), Art. 99–101.

- ^ a b "Official website of the Autonomous Region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia".

- ^ Godoberi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ 11 million in Greece, out of 13.4 million in total. Greek at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Hinuq at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Hungarian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Hunzib at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Icelandic at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Ingrian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Ingush at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Irish at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Istriot at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Istro-Romanian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Italian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Judeo-Italian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Judaeo-Spanish at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ SIL Ethnologue: "Not the dominant language for most. Formerly the main language of Sephardic Jewry. Used in literary and music contexts." ca. 100k speakers in total, most of them in Israel, small communities in the Balkans, Greece, Turkey and in Spain.

- ^ Kabardian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Kaitag at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Oirat at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Karata at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Karelian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Karachay-Balkar at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Kashubian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ About 10 million in Kazakhstan. Kazakh at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required). Technically, the westernmost portions of Kazakhstan (Atyrau Region, West Kazakhstan Region) are in Europe, with a total population of less than one million.

- ^ Khwarshi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ 220,000 native speakers out of an ethnic population of 550,000. Combines Komi-Permyak (koi) with 65,000 speakers and Komi-Zyrian (kpv) with 156,000 speakers. Komi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Kubachi at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)