Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

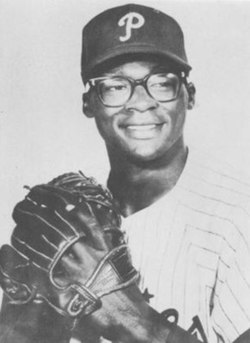

Dick Allen

View on Wikipedia

Richard Anthony Allen (March 8, 1942 – December 7, 2020), nicknamed "Crash" and "the Wampum Walloper", was an American professional baseball player. During his 15-year Major League Baseball (MLB) career, he played as a first baseman and third baseman, most notably for the Philadelphia Phillies and Chicago White Sox, and was one of baseball's top sluggers of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Key Information

A seven-time All-Star player, Allen began his career as a Phillie by being selected 1964 National League (NL) Rookie of the Year and in 1972 was the American League (AL) Most Valuable Player with the Chicago White Sox. He led the AL in home runs twice; the NL in slugging percentage once and the AL twice; and each major league in on-base percentage once apiece. Allen's career .534 slugging percentage was among his era's highest in an age of comparatively modest offensive production. The Phillies retired Allen's uniform number 15 on September 3, 2020, a few months before his death. On July 27, 2025, Allen was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.[1]

Early life

[edit]Allen was born in Wampum, Pennsylvania, one of nine children of Era and Coy Allen, a truck driver. After his parents divorced, he was mainly raised by his mother who worked as a housekeeper to support her children. Allen grew up in Chewton, Pennsylvania, a small village just outside Wampum.[2]

He attended Wampum High School where, along with his brothers Hank and Ron, he was a star basketball player at the school; all three brothers earned All-State honors. In the 1958 and 1960 seasons, Allen captained the basketball team, leading them to the state championship and earning All-American honors.[2]

Despite their prowess in basketball, the brothers chose to prioritize baseball as, at the time, baseball paid better and they wanted to buy their mother a new house. Hank became an outfielder for three teams in the American League while Ron briefly played first base for the 1972 St. Louis Cardinals. Dick was scouted by Phillies scout Jack Ogden who convinced the team to sign Allen in 1960 for a $70,000 bonus.[2]

MLB career

[edit]Philadelphia Phillies

[edit]Allen faced racial harassment while playing for the Phillies' minor league affiliate in Little Rock; residents sent death threats to Allen, the local team's first black player.

His first full season in the majors, 1964, ranks among the greatest rookie seasons ever.[3] He led the league in runs (125), triples (13), extra base hits (80), and total bases (352); Allen finished in the top five in batting average (.318), slugging average (.557), hits (201), and doubles (38) and won Rookie of the Year. Playing for the first time at third base, he led the league with 41 errors. Along with outfielder Johnny Callison and pitchers Chris Short and Jim Bunning, Allen led the Phillies to a six-and-a-half game hold on first place with 12 games to play in an exceptionally strong National League. The 1964 Phillies then lost ten straight games and finished tied for second place. The Phillies lost the first game of the streak to the Cincinnati Reds when Chico Ruiz stole home with Frank Robinson batting for the game's only run. In Allen's autobiography (written with Tim Whitaker), Crash: The Life and Times of Dick Allen, Allen stated that the play "broke our humps".[4] Despite the Phillies' collapse, Allen hit .438 with 5 doubles, 2 triples, 3 home runs and 11 RBI in those last 12 games.

Allen hit a two-run home run off the Cubs' Larry Jackson on May 29, 1965[5] that cleared the Coke sign on Connie Mack Stadium's left-center field roof. That home run, an estimated 529-footer, inspired Willie Stargell to say: "Now I know why they (the Phillies fans) boo Richie all the time. When he hits a home run, there's no souvenir."[6]

While playing for Philadelphia, Allen appeared on several All-Star teams including the 1965–67 teams (in the latter of these three games, he hit a home run off Dean Chance). He led the league in slugging (.632), OPS (1.027) and extra base hits (75) in 1966.[7]

Non-baseball incidents soon marred Allen's Philadelphia career. In July 1965, he got into a fistfight with teammate Frank Thomas. According to two teammates who witnessed the fight, Thomas swung a bat at Allen, hitting him in the shoulder. Johnny Callison said, "Thomas got himself fired when he swung that bat at Richie. In baseball you don't swing a bat at another player—ever." Pat Corrales confirmed that Thomas hit Allen with a bat and added that Thomas was a "bully" known for making racially divisive remarks. Allen and his teammates were not permitted to give their side of the story under threat of a heavy fine. The Phillies released Thomas the next day. That not only made the fans and local sports writers see Allen as costing a white player his job, but freed Thomas to give his version of the fight.[8] In an hour-long interview aired December 15, 2009, on the MLB Network's Studio 42 with Bob Costas, Allen asserted that he and Thomas had since become good friends.[9]

Allen's name was a source of controversy: he had been known since his youth as "Dick" to family and friends, but the media referred to him upon his arrival in Philadelphia as "Richie".[10] After leaving the Phillies, he asked to be called "Dick", saying Richie was a little boy's name. In his dual career as an R&B singer, the label on his records with the Groovy Grooves firm slated him as "Rich" Allen.[11]

Some Phillies fans, known for being tough on hometown players even in the best of times, exacerbated Allen's problems. Initially the abuse was verbal, with obscenities and racial epithets. Eventually Allen was greeted with showers of fruit, ice, refuse, and even flashlight batteries as he took the field. He began wearing his batting helmet even while playing his position in the field, which gave rise to another nickname, "Crash Helmet", shortened to "Crash".[10]

He almost ended his career in 1967 after mangling his throwing hand by pushing it through a car headlight.[12] Allen was fined $2,500 and suspended indefinitely in 1969 when he failed to appear for the Phillies twi-night doubleheader game with the New York Mets. Allen had gone to New Jersey in the morning to see a horse race, and got caught in traffic trying to return.[13]

St. Louis Cardinals and Los Angeles Dodgers

[edit]Allen finally had enough, and demanded the Phillies trade him. They sent him to the Cardinals in a trade before the 1970 season. Even this deal caused controversy, though not of Allen's making, since Cardinals outfielder Curt Flood refused to report to the Phillies as part of the trade. (Flood then sued baseball in an unsuccessful attempt to overthrow the reserve clause and to be declared a free agent.) Coincidentally, the player the Phillies received as compensation for Flood not reporting, Willie Montañez, hit 30 home runs as a 1971 rookie to eclipse Allen's Phillies rookie home run record of 29, set in 1964.[14] Allen earned another All-Star berth in St. Louis.[7]

Decades before Mark McGwire, Dick Allen entertained the St. Louis fans with some long home runs, at least one of them landing in the seats above the club level in left field. Nevertheless, the Cardinals traded Allen to the Los Angeles Dodgers before the 1971 season for 1969 NL Rookie of the Year Ted Sizemore and young catcher Bob Stinson. Allen had a relatively quiet season in 1971 although he hit .295 for the Dodgers.[7]

Chicago White Sox

[edit]Allen was acquired by the White Sox from the Dodgers for Tommy John and Steve Huntz at the Winter Meetings on December 2, 1971.[15] For various reasons, his previous managers had shuffled him around on defense, playing him at first base, third base, and the outfield in no particular order – a practice which almost certainly weakened his defensive play, and which may have contributed to his frequent injuries, not to mention his perceived bad attitude.[citation needed] Sox manager Chuck Tanner's low-key style of handling ballplayers made it possible for Allen to thrive, for a while, on the South Side. Tanner decided to play Allen exclusively at first base, which allowed him to concentrate on hitting. That first year, his first in the American League (AL), Allen almost single-handedly lifted the entire team to second place in the AL West, as he led the league in home runs (37) (setting a team record), RBI (113), walks (99), on-base percentage (.420), slugging percentage (.603), and on-base plus slugging percentage (1.023), while winning a well-deserved MVP award. However, the Sox fell short at the end and finished 5+1⁄2 games behind the World Series–bound Oakland Athletics.[16]

Allen's feats during his years with the White Sox – particularly in that MVP season of 1972 – are spoken of reverently by South Side fans who credit him with saving the franchise for Chicago (it was rumored to be bound for St. Petersburg or Seattle at the time).[17] His powerful swing sent home runs deep into some of cavernous old Comiskey Park's farthest reaches, including the roof and even the distant (445 feet (136 m)) center field bleachers, a rare feat at one of baseball's most pitcher-friendly stadiums. On July 31, 1972, Allen became the first player in baseball's "modern era" to hit two inside-the-park home runs in one game. Both homers were hit off Bert Blyleven in the White Sox' 8–1 victory over the Minnesota Twins at Metropolitan Stadium. On July 6, 1974, at Detroit's Tiger Stadium, he lined a homer off the roof façade in deep left-center field at a linear distance of approximately 415 feet (126 m) and a height of 85 feet (26 m).[18]

On February 27, 1973, Allen became the highest-paid player in baseball, signing a 3-year $750,000 contract. His $250,000 AAV was a record at the time of the contract's signing.[19] The Sox were favored by many to make the playoffs in 1973, but those hopes were dashed due in large measure to the fractured fibula that Allen suffered in June. (He tried to return five weeks after injuring the leg in a collision with Mike Epstein of the California Angels, but the pain ended Allen's season after just one game in which he batted 3-for-5.) In 1974, despite his making the AL All-Star team in each of the three years with the Sox, Allen's stay in Chicago ended in controversy when he left the team on September 14 with two weeks left in the season. In his autobiography, Allen blamed his feud with then third-baseman/Designated hitter Ron Santo, who was playing a final, undistinguished season with the White Sox after leaving the crosstown Chicago Cubs.[20]

With Allen's intention to continue playing baseball uncertain, the White Sox reluctantly sold his contract to the Atlanta Braves for only $5,000, despite the fact that he had led the league in home runs, slugging (.563), and OPS (.938). Allen refused to report to the Braves and announced his retirement.[17]

Return to the Phillies

[edit]The Phillies coaxed Allen out of retirement for the 1975 season. The lay-off and effects of his broken leg in 1973 hampered his play. His numbers improved in 1976, a Phillies division winner, as he hit 15 home runs and batted .268 in 85 games.[7] He continued his tape measure legacy during his second go-round with the Phillies. On August 22, 1975, Allen smashed a homer into the upper deck at San Diego Stadium, as the Phillies beat the Padres 6-5.[21]

Oakland Athletics

[edit]Allen played in 54 games and hit five home runs with 31 RBI with a .240 batting average during his final season, for the Oakland Athletics in 1977 before leaving the team abruptly in June of that season.[7] His final day as a player was on June 19, playing both games of a doubleheader, against the White Sox. In five total plate appearances, he had two hits, with his final hit being a single in the eighth inning.[22][23]

Career statistics and honors

[edit]During a pitching-dominant era, Allen was considered one of the top sluggers of the 1960s and 1970s era. He finished his career with 351 home runs and a .534 slugging percentage.[7]

Allen's number 15 was retired by the Phillies in September 2020.[24] He was inducted into the Baseball Reliquary's Shrine of the Eternals in 2004.[25]

| Category | Games | AB | Runs | Hits | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | CS | BB | SO | AVG | OBP | SLG | OPS | E | FLD% | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1,749 | 6,332 | 1,099 | 1,848 | 320 | 79 | 351 | 1,119 | 133 | 52 | 894 | 1,556 | .292 | .378 | .534 | .912 | 245 | .975 | [7] |

Hall of Fame candidacy

[edit]Sabermetrician Bill James rated Dick Allen as the second-most controversial player in baseball history, behind Rogers Hornsby.[26] Allen had the highest slugging percentage among players eligible for but not in the National Baseball Hall of Fame until Albert Belle became eligible in 2006.[27]

Allen Barra wrote that a "growing body of baseball historians think that Dick Allen is the best player eligible for the Hall of Fame".[28] The arguments usually centered around his very high career averages, batting (.292), slugging (.534), and on-base (.378). They also state that he began his career during the mid-1960s, a period so dominated by pitchers that it is sometimes called the "second dead ball era".[29] Of the major league batters with 500 or more career home runs whose play intersected Dick Allen's career at the beginning or end, only Mickey Mantle's lifetime OPS+ of 172 topped Dick Allen's lifetime 156 OPS+.[30] Allen also played some of his career in pitcher-friendly parks such as Busch Memorial Stadium, Dodger Stadium, and Comiskey Park.[31]

In addition to hitting for high offensive percentages, Allen displayed prodigious power. Before scientific weight training, muscle-building dietary supplements, and anabolic steroids, Allen boasted a muscular physique along the lines of Mickey Mantle and Jimmie Foxx. Baseball historian Bill Jenkinson ranks Allen with Foxx and Mantle, and just a notch below Babe Ruth, as the four top long-distance sluggers ever to wield a baseball bat.[32] A segment of MLB Network's Prime 9 concurred with Jenkinson's findings. On that same broadcast, Willie Mays stated that Allen hit a ball harder than any player he had ever seen.[33] Dick Allen, like Babe Ruth, hit with a rather heavy bat. Allen's 40-ounce bat bucked the Ted Williams-inspired trend of using a light bat for increased bat speed. Allen combined massive strength and body torque to produce bat speed and drive the ball. Two of his drives cleared Connie Mack Stadium's 65-foot-high (20 m) left-field grandstand.[32] Allen also cleared that park's 65-foot-high right-center field scoreboard twice, a feat considered virtually impossible for a right-handed hitter.[32]

Detractors of Allen's Hall of Fame credentials argue that his career was not as long as most Hall of Famers, and therefore lacked the career cumulative numbers that others do. They further argue that the controversies surrounding him negatively impacted his teams.[34]

Hall of Fame player Willie Stargell countered with a historical perspective of Dick Allen's time: "Dick Allen played the game in the most conservative era in baseball history. It was a time of change and protest in the country, and baseball reacted against all that. They saw it as a threat to the game. The sportswriters were reactionary too. They didn't like seeing a man of such extraordinary skills doing it his way. It made them nervous. Dick Allen was ahead of his time. His views and way of doing things would go unnoticed today. If I had been manager of the Phillies back when he was playing, I would have found a way to make Dick Allen comfortable. I would have told him to blow off the writers. It was my observation that when Dick Allen was comfortable, balls left the park."[35]

The two managers for whom Allen played the longest—Gene Mauch of the Phillies and Chuck Tanner of the White Sox—agreed with Willie Stargell that Allen was not a "clubhouse lawyer" who harmed team chemistry. Asked if Allen's behavior ever had a negative influence on the team, Mauch said, "Never. Dick's teammates always liked him. I'd take him in a minute."[28] According to Tanner, "Dick was the leader of our team, the captain, the manager on the field. He took care of the young kids, took them under his wing. And he played every game as if it was his last day on earth."[36]

Hall of Fame player Orlando Cepeda agreed, saying to author Tim Whitaker, "Dick Allen played with fire in his eyes."[37]

Hall of Fame teammate Goose Gossage also confirmed Tanner's view. In an interview with USA TODAY Sports, Gossage said: "I've been around the game a long time, and he's the greatest player I've ever seen play in my life. He had the most amazing season (1972) I've ever seen. He's the smartest baseball man I've ever been around in my life. He taught me how to pitch from a hitter's perspective, and taught me how to play the game right. There's no telling the numbers this guy could have put up if all he worried about was stats. The guy belongs in the Hall of Fame."[38]

Another of Allen's ex-White Sox teammates, pitcher Stan Bahnsen, said, "I actually thought that Dick was better than his stats. Every time we needed a clutch hit, he got it. He got along great with his teammates and he was very knowledgeable about the game. He was the ultimate team guy."[39]

Another Hall of Fame teammate, Mike Schmidt, credited Dick Allen in his 2006 book, Clearing the Bases, as his mentor.[40] In Schmidt's biography, written by historian William C. Kashatus, Schmidt fondly recalls Allen mentoring him before a game in Chicago in 1976, saying to him, "Mike, you've got to relax. You've got to have some fun. Remember when you were just a kid and you'd skip supper to play ball? You were having fun. Hey, with all the talent you've got, baseball ought to be fun. Enjoy it. Be a kid again." Schmidt responded by hitting four home runs in the game. Schmidt is quoted in the same book, "The baseball writers used to claim that Dick would divide the clubhouse along racial lines. That was a lie. The truth is that Dick never divided any clubhouse."[41]

BBWAA consideration

[edit]Allen was included in 1983 Baseball Hall of Fame balloting for consideration by the Baseball Writers' Association of America (BBWAA). He received 14 votes out of the 374 ballots cast (3.7%).[42] He was not on the 1984 ballot, but returned in 1985 and remained on the ballot until 1997. He never received more than 18.9% of the vote (75% is required for election).

Committee consideration

[edit]In 2010, the Baseball Hall of Fame established a Golden Era Committee (one of several new committees replacing the prior Veterans Committee), to vote on the possible Hall of Fame induction of previously overlooked candidates who played between 1947 and 1972. Beginning in December 2011, this 16-member committee voted every three years on 10 nominated candidates from the era, selected by the BBWAA's Historical Overview Committee. Allen was first considered in December 2014 (for the class of 2015).[43] Allen and former outfielder Tony Oliva both fell one vote short of the 12 required votes, as no one was elected by the committee.[44][45]

In 2016, the Golden Era Committee was replaced by the Golden Days Committee (1950–1969) to vote on 10 candidates beginning in December 2020 (for the class of 2021).[46] In August 2020, the Hall of Fame rescheduled the committee's first winter meeting voting to December 2021 (for the class of 2022), due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[46][47] On December 5, 2021, results of Golden Days Committee voting was released; Allen again fell one vote short of election, garnering 11 votes from the 16-member committee.[48]

He appeared on the Classic Baseball Era Committee's 2025 ballot on December 8, 2024, and was elected with 13 out of 16 votes. He was formally inducted on July 27, 2025.[49][50]

Music career

[edit]Dick Allen sang professionally in a high, delicate tenor. The tone and texture of his voice has drawn comparisons to Harptones' lead singer Willie Winfield.[51] During Allen's time with the Sixties-era Phillies, he sang lead with a doo-wop group called The Ebonistics. "Rich Allen and The Ebonistics" sang professionally at Philadelphia night clubs. He once entertained during halftime of a Philadelphia 76ers basketball game. The Philadelphia Inquirer printed a review of his performance:

Here came Rich Allen. Flowered shirt. Tie six-inches (152 mm) wide. Hiphugger bell-bottomed pants. A microphone in his hands. Rich Allen, the most booed man in Philadelphia from April to October, when Eagles coach Joe Kuharich takes over, walked out in front of 9,557 people at the Spectrum last night to sing with his group, The Ebonistics, and a most predictable thing happened. He was booed. Two songs later though, a most unpredictable thing happened. They cheered Rich Allen. They cheered him as warmly as they have ever cheered him for a game-winning home run."[52]

Although his music career was not as substantial or long-lasting as that of Milwaukee Braves outfielder Lee Maye, Allen gained lasting praise for recording a 45 single on the Groovey Grooves label (160-A, "Rich Allen and the Ebonistics") titled "Echo's of November" (misspelled Echoes) which was released in 1968.[53] The song name is featured in the Phillies' official hundred-year anniversary video and the novel '64 Intruder.[54] In 2010, Brazilian pop star Ana Volans re-recorded Echoes of November; her rendition sold briskly in Brazil, and the CD's jacket contains a dedication to Dick Allen and his Hall of Fame candidacy).[55]

Personal life

[edit]Allen first married his classmate Barbara Moore with whom he had three children: sons Richard Jr. and Eron, and daughter Terri; their marriage ended in divorce.[56] Terri Allen was murdered outside her apartment in Largo, Maryland, by her boyfriend in a murder-suicide in 1991.[57]

His marriage to his second wife, Willa (née King), lasted 33 years. The couple lived in Wampum, Pennsylvania.[2][58] He died at his home in Wampum on December 7, 2020, at age 78.[59][60]

See also

[edit]- List of Chicago White Sox award winners and league leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual fielding errors leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career intentional bases on balls leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career OPS leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career slugging percentage leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career strikeouts by batters leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career WAR leaders

- List of Philadelphia Phillies award winners and league leaders

- St. Louis Cardinals award winners and league leaders

References

[edit]- ^ "Dick Allen, Dave Parker elected to National Baseball Hall of Fame by Classic Baseball Era Committee". baseballhall.org. December 8, 2024. Retrieved December 8, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Dick Allen (SABR BioProject)". Society for American Baseball Research.

- ^ Swaine, Rick (1998). "The Ill-Fated Rookie Class of 1964". rickswaine.com. Vol. 27. Rick Swaine. Archived from the original on June 24, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ^ Allen, Dick, and Whitaker, Tim. Crash: The Life and Times of Dick Allen (Ticknor & Fields, 1989), p. 55

- ^ "Chicago Cubs at Philadelphia Phillies Box Score, May 29, 1965". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Willie Stargell Quotes". baseball-almanac.com. Baseball Almanac. January 1975. Retrieved January 13, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Dick Allen stats". baseball-reference.com. Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ Wright, Craig R.: "Dick Allen: Another View", SABR's Baseball Research Journal vol. 24, 1995, republished with permission at White Sox Interactive Archived April 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ MLB Network's "Studio 42 with Bob Costas", hour-long interview with Dick Allen first aired December 15, 2009.

- ^ a b Cody Swartz (April 28, 2009). "Dick Allen: What Could Have Been". Bleacher Report. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ Rich Allen & The Ebonistics "Echoes Of November," Groovy Grooves, 1968.

- ^ Jay Jaffe (July 26, 2017). "The Cooperstown Casebook: Case Study: Dick Allen". Baseball Prospectus. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ "Today in Baseball History June 24th". nationalpastime.com. Retrieved June 24, 2013.

- ^ Schlegel, John. "Powerful starts: Greatest homer tallies by rookies," Major League Baseball.com (July 11, 2014).

- ^ Durso, Joseph. "White Sox Add Bahnsen, Ship McKinney to Yanks," The New York Times, Friday, December 3, 1971. Retrieved December 4, 2021

- ^ "1972 AL Team Statistics". baseball-reference.com. Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Paul Sullivan; Paul Skrbina (December 7, 2020). "Dick Allen, the Chicago White Sox legend who won American League MVP honors in 1972, dies at 78". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ Jenkinson, Bill: The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Homeruns, Carrol and Graf, 2007

- ^ "Today in White Sox History: February 27". February 27, 2022.

- ^ Allen & Whitaker, Crash, pp. 148–151.

- ^ "Philadelphia Phillies at San Diego Padres Box Score, August 22, 1975". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Dick Allen 1977 Batting Game Logs". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ "Oakland Athletics at Chicago White Sox Box Score, June 19, 1977". Baseball-Reference.com.

- ^ Mark Feinsand (September 3, 2020). "Long time coming: Phils retire Allen's No. 15". Major League Baseball. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "Shrine of the Eternals – Inductees" Archived September 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Baseball Reliquary. www.baseballreliquary.org. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ James, Bill (2001). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. Free Press. p. 438. ISBN 9780684806976.

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for Slugging %". baseball-reference.com. Baseball Reference. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Barra, Allen (July 28, 2005). "The Best Player Eligible for the Hall of Fame". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ [James Bill, The New Bill James Historical Abstract/page 249/Free Press/2001]

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for On-Base Plus Slugging". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ Kashatus, William C. "Why Dick Allen Never Reached the Hall," Archived August 8, 2014, at the Wayback Machine History News Service (August 8, 2005).

- ^ a b c Jenkinson, Bill (2007). The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs. Carrol and Graf.

- ^ Prime 9 (MLB Network, February 7, 2011).

- ^ McLaughlin, Dan. "BASEBALL: Canseco and the Dick Allen Problem," Archived October 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine Baseball Crank (May 14, 2002).

- ^ Crash. The Life and Times of Dick Allen/Whitaker/Ticknor and Fields/1989/pg 185

- ^ Wright, Craig R. "Dick Allen: Another View", originally published in SABR Magazine, now archived at White Sox Interactive Archived April 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ The Life and Times of Dick Allen/Tim Whataker/Ticknor and Fields/1989/pg 186

- ^ Nightengale, Bob. "Dick Allen's hard road may take Hall of Fame turn". USA Today.

- ^ Liptak, Mark. "Flashing Back.... with Stan Bahnsen," Archived January 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine White Sox Interactive. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ Schmidt, Mike and Waggoner, Glen. Clearing the Bases (HarperCollins, 2009).

- ^ Kashatus, William C. Mike Schmidt: Philadelphia's Hall of Fame Third Baseman (McFarland & Co., Inc., 1999).

- ^ "BBWAA Results by Year – 1983". baseballhall.org. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011 – via Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Golden Era Committee Candidates Announced". baseballhall.org. Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- ^ "All 10 baseball Hall candidates fall short - SFGate". www.sfgate.com. Archived from the original on December 9, 2014.

- ^ "Golden Era Committee Announces Result". baseballhall.org. December 2014.

- ^ a b "Hall of Stats: Upcoming Elections". hallofstats.com. Hall of Stats. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ "Era Committee elections rescheduled to 2021". MLB.com. August 24, 2020.

- ^ "Fowler, Hodges, Kaat, Miñoso, Oliva, O'Neil Elected to Hall of Fame". baseballhall.org. December 5, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2021.

- ^ "Classic Baseball Era Committee Candidates Announced". baseballhall.org. November 4, 2024. Retrieved November 4, 2024.

- ^ "Ichiro, Sabathia, Wagner, Parker, Allen inducted into Baseball Hall of Fame". The Athletic. July 27, 2025. Retrieved July 28, 2025.

- ^ http://www.wogl.cbslocal.com Archived March 31, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Michael Clair (December 7, 2020). "Allen was one of the coolest to ever play". Major League Baseball. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ Dosage Magazine, 2020

- ^ Gregory T. Glading/'64 Intruder/University Editions/1995

- ^ Ana Volans official website. Archived May 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schudel, Matt (December 8, 2020). "Dick Allen, embattled baseball star of the 1960s and '70s, dies at 78". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Ex-Phillie's Daughter Slain in Maryland; Was Pennridge Grad". The Morning Call. June 7, 1991.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (December 7, 2020). "Dick Allen, 78, Dies; Baseball Slugger Withstood Bigotry". The New York Times.

- ^ "Former MVP, Rookie of the Year Dick Allen Dies at 78". Sports Illustrated. December 7, 2020. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ Breen, Matt (December 7, 2020). "Phillies legend Dick Allen dies at 78". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved December 9, 2020.

Further reading

[edit]Articles

[edit]- Keith, Larry (May 19, 1975). "Philadelphia Story: Act II". Sports Illustrated.

- Gelb, Matt (September 4, 2020). "Ahead of their time: Dick Allen and the Philly sportswriter who asked why in '69". The Athletic.

Books

[edit]- Allen, Dick; Whitaker, Tim (1989). Crash: The Life and Times of Dick Allen. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 978-0899196572.

- Kashatus, William C. (2004). September Swoon: Richie Allen, the 1964 Phillies and Racial Integration. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0271027425.

- Nathanson, Mitchell (2016). God Almighty Hisself: The Life and Legacy of Dick Allen. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812248012.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from MLB · ESPN · Baseball Reference · Fangraphs · Baseball Reference (Minors) · Retrosheet · Baseball Almanac

- Dick Allen at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

Dick Allen

View on GrokipediaEarly life

Childhood and family in Pennsylvania

Richard Anthony Allen was born on March 8, 1942, in Crescentdale, a rural farming and mining community near Wampum in Lawrence County, Pennsylvania.[6] He grew up primarily in the adjacent village of Chewton, a small working-class enclave of about 488 residents located 30 miles northwest of Pittsburgh.[7] Allen was one of nine children of Coy Allen, a truck driver whose income proved inconsistent, and Era Allen (née Rhodes Craine), who supported the family as a domestic worker and housekeeper following her divorce from Coy.[7] [8] [9] His siblings included brothers such as Harold (Hank), Ron, and Coy, several of whom shared his athletic inclinations and later pursued professional sports.[7] [6] The Allen family, one of the few African American households in the predominantly white area, navigated post-Great Depression economic hardships through collective effort, including farm chores like tending livestock and crops on their small plot.[8] [9] Era's reliance on low-wage labor underscored the household's financial precarity, yet she instilled a rigorous work ethic and self-reliance in her children, emphasizing independence amid limited opportunities.[7] [8] This environment of manual labor, familial duty, and modest resources cultivated Allen's early resilience, as the siblings contributed to household stability while facing the constraints of rural industrial life in western Pennsylvania.[7] [9]Introduction to baseball and name change

Richard Anthony Allen, born on March 8, 1942, in Wampum, Pennsylvania, demonstrated exceptional athletic talent during his high school years at Wampum High School, excelling in baseball as a shortstop alongside basketball and other sports.[7] His prowess on the diamond drew the attention of Philadelphia Phillies scout Jack Ogden, who recognized his potential as a multi-sport standout from a family of athletes.[10] Immediately following his graduation from Wampum High School in May 1960, the 18-year-old Allen signed a professional contract with the Phillies, receiving a substantial $60,000 signing bonus that marked him as a top shortstop prospect with notable raw power and speed.[10] Early evaluations highlighted his athletic gifts, including quickness around the infield and the ability to drive the ball with force, though scouts anticipated refinements in his defensive positioning as he transitioned to professional play.[7] This signing represented a pivotal shift from amateur competition to organized baseball, positioning Allen as one of the organization's high-upside investments. As Allen's profile rose with his entry into professional ranks around 1963, he deliberately adopted the name "Dick" publicly, distancing himself from the "Richie" moniker imposed by media and others since his signing.[7] He expressed a preference for "Dick," his longstanding personal name derived from Richard, viewing "Richie" as an unwelcome diminutive that failed to reflect his maturing identity amid increasing scrutiny.[7] This rebranding underscored his assertion of autonomy, occurring as he navigated the demands of fame and professionalism without altering his core self-presentation from high school days.[11]Minor league career

Signing with Phillies and initial development

Allen signed with the Philadelphia Phillies as an amateur free agent in June 1960, shortly after graduating from Wampum High School in Pennsylvania, for a reported bonus of $70,000, reflecting the organization's high evaluation of his raw talent as an 18-year-old shortstop with exceptional bat speed and power potential.[12][7] He was immediately assigned to the Phillies' lowest minor league affiliate, the Elmira Pioneers of the Class-D New York-Penn League, where he adapted to professional play while primarily handling shortstop duties amid ongoing defensive refinement needs.[13] In his first three minor league seasons (1960–1962), spanning stops including Elmira and Williamsport, Allen compiled a .279 batting average with 49 home runs and 245 RBIs, showcasing emerging plate discipline—evidenced by walk rates exceeding his strikeouts in early outings—and consistent extra-base power that marked him as the Phillies' premier hitting prospect despite erratic fielding at shortstop, where errors stemmed from range and consistency limitations rather than effort.[7] The organization invested heavily in his development, promoting him progressively through affiliates like the Magic Valley Cowboys and Arkansas Travelers, prioritizing his offensive upside over immediate defensive polish; scouts noted his ability to drive the ball to all fields with pull-side power, drawing comparisons to established sluggers, even as inconsistencies in positioning hinted at future adjustments.[14] By 1963, in Triple-A Buffalo, he led the International League with 33 home runs and 97 RBIs while batting .289, solidifying the Phillies' commitment to transitioning him toward third base to leverage his bat in a lineup needing right-handed production, a shift initiated amid recognition that his arm strength suited corner infield but shortstop demands exposed glove work gaps.[15]Experiences with racism in Little Rock

In 1963, Dick Allen was assigned to the Philadelphia Phillies' Double-A affiliate, the Arkansas Travelers in Little Rock, becoming the team's first Black player amid the lingering racial tensions following the 1957 Little Rock Central High School desegregation crisis.[16] Upon arrival, he encountered segregated living arrangements, staying with a local Black family while white teammates lodged elsewhere, and faced restrictions such as needing a white teammate to dine at certain restaurants.[16] The city's segregationist governor, Orval Faubus, threw out the ceremonial first pitch on opening night, setting a tone of hostility reinforced by fans displaying placards reading "Don’t Negro-ize Baseball" and "[Negro] Go Home."[7] [16] Allen faced immediate and escalating threats, including racial taunts from the crowd, harassing encounters at local stores, stops by police, and a threatening note left on his car warning, "Don’t come back again, [n-word]."[7] [16] Fans escalated to physical endangerment by hurling objects such as batteries, coins, rocks, and bottles toward him during games, prompting Allen to wear a batting helmet for protection even while playing in the outfield—a precaution he maintained throughout his time there.[17] [18] These incidents, coupled with death threats, led him to briefly consider quitting baseball, but encouragement from his brother Hank Allen persuaded him to persist, viewing perseverance as aligned with his talents.[16] [7] Despite the turmoil, Allen demonstrated resilience at the plate, batting .289 with a .341 on-base percentage and .550 slugging percentage, while leading the league with 33 home runs, 12 triples, 97 RBIs, and 299 total bases; he was voted the Travelers' Most Valuable Player by fans.[16] [7] This performance under duress highlighted his ability to channel adversity into productivity, though the pervasive hostility in Arkansas—his first significant exposure to Southern racism—instilled a lasting distrust of institutional authority and fan expectations.[11][7]Major League Baseball career

Philadelphia Phillies (1963–1969)

Allen made his major league debut with the Philadelphia Phillies on September 3, 1963, appearing in 10 games that season and batting .292 with one triple.[2] In 1964, his first full season, he established himself as a star third baseman, slashing .302/.382/.557 with 125 runs scored, 201 hits, 13 triples, 29 home runs, and 352 total bases, leading the National League in the latter three categories despite committing a league-high 41 errors at the position.[1][17] These efforts earned him the National League Rookie of the Year Award with 18 of 20 first-place votes, though he finished second in MVP voting behind St. Louis Cardinals third baseman Ken Boyer.[17] Amid the Phillies' infamous late-season collapse—blowing a 6½-game lead with 12 games remaining by losing 10 straight—Allen maintained strong production, hitting .438 with three home runs over the final 12 games.[19] From 1965 to 1968, Allen sustained elite offensive output, leading the NL in total bases in 1966 (379) and slugging percentage (.632), while posting an OPS of 1.027 that year.[2][7] His adjusted OPS+ exceeded 170 in multiple seasons during this span, reflecting dominance relative to league and park-adjusted standards.[1] In 1968, he slashed .317/.399/.603 with 33 home runs and 95 RBIs, finishing third in the NL in home runs and fourth in batting average, positioning him near a Triple Crown contention before late-season frustrations.[1] Incidents of on-field sulking following defensive miscues and public drinking began drawing media scrutiny, contributing to perceptions of inconsistent effort.[7] Tensions escalated in 1969 under manager Bob Skinner, with whom Allen clashed repeatedly; on June 24, Allen was fined $2,500 and suspended indefinitely for missing a doubleheader against the New York Mets.[20] He remained away from the team for 26 days before meeting owner R. R. M. Carpenter on July 19 and agreeing to return with a promise of a future trade.[21] Skinner resigned in August, citing insufficient front-office backing in handling Allen.[7] The Phillies traded Allen to the St. Louis Cardinals on October 7, 1969, for second baseman Cookie Rojas, pitcher Dick Groat, and cash.[7] Over his Phillies tenure from 1963 to 1969, Allen appeared in 1,095 games, slashing .292/.381/.557 with 166 home runs and 538 RBIs.[1]

St. Louis Cardinals and Los Angeles Dodgers (1970–1971)

On February 18, 1970, the Philadelphia Phillies traded Dick Allen to the St. Louis Cardinals in exchange for second baseman Cookie Rojas and pitcher Jerry Johnson.[22] Allen, seeking a fresh start after tensions in Philadelphia, held out through much of spring training before signing a contract.[23] In 122 games for the Cardinals, he batted .279 with a .355 on-base percentage and .522 slugging percentage, hitting 34 home runs and driving in 101 runs while playing first base, third base, and left field.[1] These figures led the team in home runs, RBIs, and on-base plus slugging (.877).[24] A hamstring injury sidelined Allen for significant time in 1970, limiting his durability and contributing to his absence from the lineup in the season's final weeks.[25] With six weeks remaining, he stopped reporting to the ballpark, prompting trade rumors that manager Red Schoendienst initially denied.[26] On October 5, 1970, the Cardinals dealt Allen to the Los Angeles Dodgers for infielder Ted Sizemore and catcher Bob Stinson, marking his second trade in less than a year and underscoring ongoing instability in his career trajectory.[22] Allen appeared in all 155 games for the Dodgers in 1971, primarily at third base, where he posted a .295 batting average, .395 on-base percentage, .468 slugging percentage, 23 home runs, and 90 RBIs, leading the team in the latter two categories.[1][27] His .863 OPS reflected offensive potency amid a lineup featuring Willie Davis and Steve Garvey, aiding a late-season push, though the Dodgers finished third in the National League West with an 89-73 record, missing the playoffs.[28] Despite these contributions, including strong baserunning, Allen received no major awards, and the team's front office prioritized pitching depth, trading him on December 2, 1971, to the Chicago White Sox for Tommy John and Steve Huntz.[7][22]Chicago White Sox (1972–1975)

Allen joined the Chicago White Sox via trade from the Los Angeles Dodgers on November 27, 1971, in exchange for Tommy John and Steve Huntz.[1] In 1972, he enjoyed a resurgent season, batting .308 with a .420 on-base percentage, .603 slugging percentage, 37 home runs, and 113 RBIs over 148 games, leading the American League in home runs, RBIs, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, and OPS (1.023).[1] These performances earned him the AL Most Valuable Player Award and an All-Star selection, while carrying the White Sox to an 86-76 record and second place in the AL West, a marked improvement from their prior seasons of sub-.500 finishes.[1] [29] Allen's leadership extended beyond statistics, as he boosted team morale and fan attendance, helping stabilize the franchise amid relocation rumors; the White Sox drew over 1.1 million fans, more than doubling the previous year's total.[29] Teammates credited his presence with fostering camaraderie and elevating overall play, transforming a previously uncompetitive roster into contenders.[30] The 1973 season began promisingly, with Allen hitting .316/.394/.612 and 16 home runs in 72 games before suffering a hairline fracture in his left leg on June 28 during a collision at first base, sidelining him for the remainder of the year.[1] [31] In 1974, he rebounded with a .301 average, 32 home runs (leading the AL), 88 RBIs, and a .938 OPS over 128 games, earning another All-Star nod despite missing time due to injuries.[1] [5] By 1975, Allen's production declined to .233/.327/.385 with 12 home runs in 119 games, hampered by lingering injuries including a prior Achilles issue, leading to his sale to the Philadelphia Phillies on June 15.[1] [32] Over his White Sox tenure, he averaged over 30 home runs per full season played, underscoring a peak of sustained power hitting.[1]Return to Philadelphia Phillies (1975–1976)

After retiring at the end of the 1974 season with the Chicago White Sox, Allen signed a contract with the Atlanta Braves in the spring of 1975 but refused to report to the team.[33] On May 7, 1975, the Braves traded him to the Philadelphia Phillies along with catcher Johnny Oates in exchange for outfielders Jim Essian and Barry Bonnell and $150,000.[22] Allen made his return to the Phillies lineup on May 14, 1975, against the Cincinnati Reds at Veterans Stadium, where he singled in his first at-bat amid standing ovations from a crowd of over 30,000 fans.[14] At age 33 and hampered by lingering injuries, including a chronic right shoulder problem that the Phillies had concealed during acquisition discussions, his performance fell short of his peak years.[32] In 119 games, he batted .233 with a .327 on-base percentage, .385 slugging percentage, 12 home runs, and 62 RBIs, reflecting diminished power and a high strikeout rate of 109 in 416 at-bats.[34] In 1976, Allen, now 34, showed flashes of his earlier prowess with a .268 batting average, .346 on-base percentage, .480 slugging percentage, 15 home runs, and 49 RBIs over 85 games, but early-season struggles—including a .250 average with minimal extra-base hits—were compounded by injuries and mounting tensions.[35] A July 25 collision left him dizzy and sidelined on the disabled list until September 3, exacerbating frustrations with manager Danny Ozark over platoon usage, playing time, and lineup position.[33] Conflicts escalated, including Allen's refusal to pinch-hit in April, unannounced departures from games in July, and an August incident dubbed the "Broom Closet Affair," where he alleged racial bias in Ozark's decisions, deepening team divisions.[33] Citing dissatisfaction with his role and demanding the postseason activation of teammate Tony Taylor, Allen's relationship with the organization deteriorated; following the Phillies' NLCS loss, he was informed he would not be re-signed for 1977, concluding his attempted homecoming on a note of unresolved rift amid skepticism from media and some fans wary of his past controversies in Philadelphia.[33]Oakland Athletics (1977)

Allen signed with the Oakland Athletics as a free agent on March 16, 1977.[22] At age 35, he appeared in 54 games primarily at first base, posting a .240 batting average with 5 home runs and 31 runs batted in over 171 at bats.[1] His performance reflected the physical toll of a 15-year career marked by injuries, including chronic issues with his lower back and legs that limited his mobility and power.[1] Allen's final major league appearance came on June 19, 1977, after which he did not play further that season or return in 1978, effectively retiring.[36] The Athletics released him formally on March 28, 1978, ending his playing days without notable conflicts, in contrast to prior tensions with management elsewhere.[22] Over his career, Allen compiled a .292 batting average, .378 on-base percentage, .534 slugging percentage, and 351 home runs, totals achieved despite frequent absences due to injury and disputes.[1]Playing style and statistical highlights

Offensive prowess and defensive versatility

Allen's hitting mechanics featured a compact swing with minimal stride and explosive bat speed, allowing him to pull pitches with exceptional force despite wielding a 40-ounce bat.[7] [11] This generated prodigious power in a pitcher-dominated era, exemplified by a 510-foot home run at Connie Mack Stadium on May 29, 1965.[7] His career adjusted OPS+ of 156 ranked him among the era's elite sluggers, matching the marks of Willie Mays and Frank Thomas, while his 58.7 WAR placed him in the top echelon of contemporaries despite injury-related absences.[1] [37] At the plate, Allen demonstrated solid discipline for a power hitter, drawing 1,319 walks against 1,563 strikeouts over 7,315 appearances, reflecting selective aggression that maximized on-base opportunities without excessive chasing.[1] His ability to hit to all fields with fast hands contributed to a .292 batting average and 351 home runs, underscoring causal efficiency in converting bat speed to exit power ahead of widespread Statcast measurement.[7] Defensively, Allen exhibited versatility across third base, first base, left field, and right field, with teams experimenting at first and outfield to mitigate his infield liabilities.[1] Primarily a third baseman early on, he led the National League with 41 errors in 1964 while transitioning to the position, though observers noted good hands and Gold Glove-level arm strength potential that went unrealized amid fielding inconsistencies.[7] [38] Later shifts to corner outfield and first base reduced error totals but highlighted his athletic adaptability over polished glove work.[1]Key awards and records

Allen earned the National League Rookie of the Year Award in 1964 after leading the league in runs scored (125), triples (13), extra-base hits (80), and total bases (352).[1] [39] He received the American League Most Valuable Player Award in 1972, leading the AL that year in home runs (37), runs batted in (113), on-base percentage (.420), and OPS (1.023).[1] [40] Allen was selected to seven All-Star Games, appearing in 1965, 1966, 1967, 1970, 1972, 1973, and 1974.[1] He led the National League in OPS (1.027) and home runs (40) in 1966, as well as slugging percentage (.632) that season.[1] In the American League, he topped slugging percentage (.603) in 1974.[1] Advanced metrics highlight Allen's offensive dominance; his JAWS score of 52.4 (average of career 58.8 WAR and seven-year peak 45.9 WAR) places him 17th all-time among third basemen.[41] [42] He ranks fifth in JAWS peak value (45.9) among third basemen.[43]Controversies and reputation

Conflicts with management and media

Allen clashed frequently with Philadelphia Phillies manager Gene Mauch over issues of discipline and personal conduct. On July 8, 1967, Mauch benched Allen for arriving late to the ballpark and appearing unfit to play, commenting that "some rest will help him."[7] These tensions contributed to Mauch's dismissal on June 15, 1968, as the manager struggled to manage Allen's independent streak and related clubhouse disruptions.[7] Mauch later described Allen's self-sabotaging tendencies as a barrier to team harmony, while Allen perceived such interventions as overly rigid attempts to curtail his autonomy.[11] The conflicts escalated in 1969 under interim manager Bob Skinner. Allen was suspended on June 24 for missing a doubleheader after attending a racetrack event, resulting in a 26-day absence and daily fines of $1,000.[7] Management cited insubordination as the core issue, viewing Allen's absences and non-compliance as patterns of unreliability that undermined team discipline.[44] Allen was reinstated on July 19 following a meeting with owner R. R. M. Carpenter, who assured him of an impending trade, which materialized in October to the St. Louis Cardinals.[7] Allen countered that managerial expectations ignored his personal circumstances and that enforcement was inconsistent. Allen also feuded with Philadelphia media over his preferred name, insisting on "Dick" rather than the juvenile-sounding "Richie," which he said made him "sound like I'm ten years old."[7] Reporters often mocked this preference, dubbing him "Richie (Call me Dick) Allen" in print, exacerbating his distrust of coverage that frequently highlighted his nightlife and alleged drinking incidents, such as rumored pre-game consumption or missed flights.[11] Allen attributed much of the negative portrayal to biased reporting that amplified minor lapses while ignoring his on-field contributions, arguing it created a narrative of irresponsibility not applied equally to others.[11] Similar reliability concerns arose during Allen's Chicago White Sox tenure (1972–1974), where management and media pressures over curfew violations and erratic availability contributed to his abrupt retirement announcement on September 14, 1974, despite a .302 batting average and 32 home runs that season.[11] Executives pointed to these patterns as evidence of unpredictability hindering team stability, echoing Phillies critiques. Allen maintained that sensationalized accounts distorted his professionalism, fueling a cycle of mutual antagonism with authority figures across franchises.[11]On-field behavior and effort concerns

Allen frequently exhibited on-field actions interpreted as lacking hustle, such as trotting rather than sprinting to first base on ground balls during his Philadelphia Phillies years in the late 1960s, which fueled perceptions of diminished effort and professionalism.[45] These incidents, including casual approaches to routine plays, drew scrutiny from observers and contributed to broader questions about his commitment, even as he posted batting averages over .300 in both 1968 (.301) and 1969 (.302).[7] [45] Further episodes involved abruptly leaving the field or bench mid-game, such as exiting a Phillies contest in the third inning on July 25, 1976, citing shoulder pain, followed by a brief absence that led to an AWOL report and fine (later rescinded).[7] Similarly, on June 19, 1977, with the Oakland Athletics, he departed the bench without permission during a game, prompting a suspension from owner Charlie Finley.[7] Such actions amplified teammate concerns, with some accounts describing Allen as fostering divisiveness by creating "warring camps" of supporters and detractors within clubhouses.[46] Critics attributed these behaviors partly to an entitlement stemming from his exceptional talent, yet empirical performance countered narratives of consistent underperformance; in 1972, amid similar critiques, Allen won American League MVP honors with the Chicago White Sox, leading the league in home runs (37), RBIs (113), and slugging percentage (.603) while batting .308.[47] [48] Others linked the conduct to physical tolls, as Allen played through chronic injuries like a 1973 hairline leg fracture and recurrent shoulder issues, often masking pain rather than fully resting.[32] [7]Racial discrimination faced and responses

During his time in the minor leagues with the Arkansas Travelers in Little Rock in 1960 and 1961, Allen, as the team's only Black player, encountered severe racial bigotry in the segregated South, including death threats, vandalism of his property, verbal abuse with racial epithets, and exclusion from local hotels, forcing him to live with a white teammate.[49][18] These experiences instilled lasting resentment, as Allen later reflected that the hostility in Little Rock—amid broader Jim Crow-era discrimination—shaped his guarded demeanor and reluctance to engage publicly, contributing to a mindset of self-protection over accommodation.[50][17] Upon reaching the major leagues with the Philadelphia Phillies in 1963, Allen faced intensified fan abuse at Connie Mack Stadium, where spectators routinely directed racial slurs at him, pelted him with batteries, bottles, and other objects—prompting him to wear a batting helmet in the outfield for protection—and dumped trash in his locker.[51][52][53] Death threats extended beyond the stadium, with fans calling his home and leaving intimidating notes on his car windshield, exacerbating the hostile environment in a city with documented racial tensions.[54][53] Media coverage often amplified these incidents into stereotypes portraying Allen as defiant or unapproachable, intertwining racial animus with critiques of his on-field effort, though empirical data shows his offensive output surged in Philadelphia despite the adversity, leading the National League in total bases in 1966 with 379.[18][55] Allen's responses emphasized personal agency amid systemic racism: he channeled the bigotry into focused power hitting—evidenced by his .292 batting average and 23 home runs in 1964 amid nightly booing—but also withdrew from fan interactions and media, fostering isolation that contemporaries argued compounded his "bad boy" reputation beyond racial factors alone.[17][4] While the discrimination was verifiably causal in eroding trust, as Allen noted in 2025 reflections wondering "how good I could have been" without it, teammates and observers like Phillies manager Gene Mauch highlighted that Allen's choices, such as public feuds and selective disengagement, sometimes exacerbated conflicts rather than solely reflecting victimhood.[4][56] This duality—real barriers met with resilient production yet self-limiting reactions—distinguishes his career trajectory from over-narratives of unmitigated oppression.[50]Hall of Fame candidacy and induction

BBWAA voting history

Dick Allen first became eligible for election to the Baseball Hall of Fame via the Baseball Writers' Association of America (BBWAA) ballot in 1983, five years after his final major league season in 1977. He garnered 14 votes out of 374 cast that year, equating to 3.7% support, well below the 75% threshold required for induction.[57] His vote totals rose modestly in subsequent years, reflecting gradual recognition of his offensive achievements amid a career abbreviated by injuries and absences totaling over 500 games across 16 seasons.[58] Allen's BBWAA support peaked in 1996 at 18.9%, his 14th year on the ballot, when voters selected him on 113 of 473 ballots amid increasing sabermetric appreciation for his .292 batting average, 351 home runs, and seven All-Star selections.[58] [59] Despite outpacing initial BBWAA support for eventual inductees like Phil Rizzuto (peaking at 38.4% after 17 years before committee election), Allen's percentages never exceeded 20%, with analyses attributing the shortfall to voter emphasis on his 1970s media portrayal as a disruptive figure over empirical metrics like his 1.040 OPS in peak seasons.[60] In 1997, Allen received fewer than 5% of votes, triggering his removal from future BBWAA ballots under the organization's rules for sustained low support.[4] This outcome highlighted a disconnect between quantitative career value—superior to several enshrined peers in rate statistics—and qualitative judgments on intangibles like leadership, as critiqued in post-ballot reviews questioning media-driven narratives' influence on writer decisions.[59]| Year | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 1983 | 3.7% |

| 1985 | 7.1% |

| 1986 | 9.6% |

| 1987 | 13.3% |

| 1988 | 12.2% |

| ... | ... |

| 1996 | 18.9% |

| 1997 | <5% |