Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

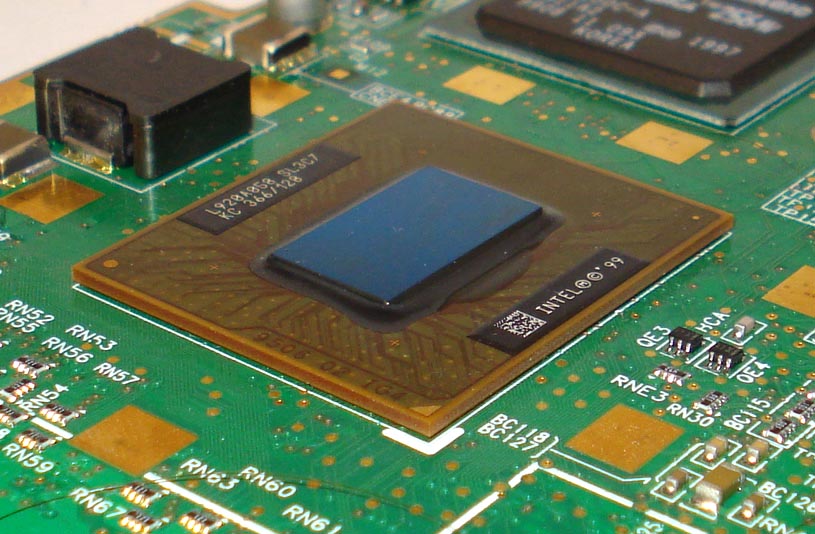

Flip chip

View on Wikipedia

Flip chip, also known as controlled collapse chip connection or its abbreviation, C4,[1] is a method for interconnecting dies such as semiconductor devices, IC chips, integrated passive devices and microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), to external circuitry with solder bumps that have been deposited onto the chip pads. The technique was developed by General Electric's Light Military Electronics Department, Utica, New York.[2] The solder bumps are deposited on the chip pads on the top side of the wafer during the final wafer processing step. In order to mount the chip to external circuitry (e.g., a circuit board or another chip or wafer), it is flipped over so that its top side faces down, and aligned so that its pads align with matching pads on the external circuit, and then the solder is reflowed to complete the interconnect. This is in contrast to wire bonding, in which the chip is mounted upright and fine wires are welded onto the chip pads and lead frame contacts to interconnect the chip pads to external circuitry.[3]

Process steps

[edit]- Integrated circuits are created on the wafer.

- Pads are metallized on the surface of the chips.

- A solder ball is deposited on each of the pads, in a process called wafer bumping

- Chips are cut.

- Chips are flipped and positioned so that the solder balls are facing the connectors on the external circuitry.

- Solder balls are then remelted (typically using hot air reflow).

- Mounted chip is "underfilled" using a (capillary, shown here) electrically-insulating adhesive.[4][5]

Comparison of mounting technologies

[edit]Wire bonding/thermosonic bonding

[edit]

In typical semiconductor fabrication systems, chips are built up in large numbers on a single large wafer of semiconductor material, typically silicon. The individual chips are patterned with small pads of metal near their edges that serve as the connections to an eventual mechanical carrier. The chips are then cut out of the wafer and attached to their carriers, typically via wire bonding such as thermosonic bonding. These wires eventually lead to pins on the outside of the carriers, which are attached to the rest of the circuitry making up the electronic system.

Flip chip

[edit]

Processing a flip chip is similar to conventional IC fabrication, with a few additional steps.[6] Near the end of the manufacturing process, the attachment pads are metalized to make them more receptive to solder. This typically consists of several treatments. A small dot of solder is then deposited on each metalized pad. The chips are then cut out of the wafer as normal.

To attach the flip chip into a circuit, the chip is inverted to bring the solder dots down onto connectors or pads on the underlying electronics or circuit board or substrate. The solder is then re-melted to produce an electrical connection, typically using a thermosonic bonding or alternatively reflow solder process.[7]

This also leaves a small space between the chip's circuitry and the underlying mounting. In many cases an electrically-insulating adhesive is then "underfilled" to provide a stronger mechanical connection, provide a heat bridge, and to ensure the solder joints are not stressed due to differential heating of the chip and the rest of the system. The underfill distributes the thermal expansion mismatch between the chip and the board, preventing stress concentration in the solder joints which would lead to premature failure.[8]

Solder balls can be mounted on the chips by separately making the balls and then attaching them to the chips by using a vacuum pick up device to pick up the balls and then placing them into a chip with flux applied on contact pads for the balls, or by wafer bumping which consists of electroplating in which seed metals are first deposited onto a wafer with the chips to be bumped. This allows the solder to adhere to the contact pads of the chips during the electroplating process. The seed metals are alloys and are deposited by sputtering onto the wafer with the chips to be bumped. A photoresist mask is used to only deposit the seed metal on top of the contact pads of the chips. The wafer then undergoes electroplating, and the photoresist layer is removed or stripped. Then the solder on the chips undergoes solder reflow to form the bumps into their final shape. Solder balls are often 75 to 500 microns in diameter.[9][10]

In 2008, High-speed mounting methods evolved through a cooperation between Reel Service Ltd. and Siemens AG in the development of a high speed mounting tape known as 'MicroTape'[1]. By adding a tape-and-reel process into the assembly methodology, placement at high speed is possible, achieving a 99.90% pick rate and a placement rate of 21,000 cph (components per hour), using standard PCB assembly equipment.

Flip-chip packages often consist of a silicon die sitting on top of a "substrate" which then sits on top of a traditional PCB. The substrate can have a Ball Grid Array (BGA) on its underside. The substrate makes the connections to the die available for use by the PCB.[11] Substates made with build up film such as Ajinomoto Build up Film (ABF), are manufactured around a core, and the film is stacked on the core in layers by vacuum lamination at high temperatures. After each layer is applied, the film is cured, and laser vias are made with CO2 or UV lasers, then the blind vias in the substrate are cleaned and the build up film is roughened chemically with a permanganate, and then copper is deposited using electroless copper plating, followed by creating a pattern on the copper using photolithography and etching, and then this process is repeated for every layer of the substrate.[12][13]

Tape-automated bonding

[edit]Tape-automated bonding (TAB) was developed for connecting dies with thermocompression or thermosonic bonding to a flexible substrate including from one to three conductive layers. Also with TAB it is possible to connect die pins all at the same time as with the soldering based flip-chip mounting. Originally TAB could produce finer pitch interconnections compared to flip chip, but with the development of the flip chip this advantage has diminished and has kept TAB to be a specialized interconnection technique of display drivers or similar requiring specific TAB compliant roll-to-roll (R2R, reel-to-reel) like assembly system.

Advantages

[edit]The resulting completed flip-chip assembly is much smaller than a traditional carrier-based system; the chip sits directly on the circuit board, and is much smaller than the carrier both in area and height. The short wires greatly reduce inductance, allowing higher-speed signals, and also conduct heat better.

Disadvantages

[edit]Flip chips have several disadvantages.

The lack of a carrier means they are not suitable for easy replacement, or unaided manual installation. They also require very flat mounting surfaces, which is not always easy to arrange, or sometimes difficult to maintain as the boards heat and cool. This limits the maximum device size.

Also, the short connections are very stiff, so the thermal expansion of the chip must be matched to the supporting board or the connections can crack.[14] The underfill material acts as an intermediate between the difference in CTE of the chip and board.

History

[edit]The process was originally introduced commercially by IBM in the 1960s for individual transistors and diodes packaged for use in their mainframe systems.[15]

Ceramic subtrates for flip-chip BGA were replaced with organic substrates to reduce costs and use existing PCB manufacturing techniques to produce more packages at a time by using larger PCB panels during manufacturing.[16] Ajinomoto Build up Film (ABF) was developed in 1999 and has become a material widely used in flip-chip packages, used for manufacturing flip-chip substrates in a semi-additive process, first pioneered by Intel.[16][17][18] Build up film helped transition the industry away from ceramic substrates, and this film is now essential in the production of organic flip-chip package substrates.[12][19]

See also

[edit]- Flip-Chip modules – Digital Equipment Corporation trademarked version

- Hybrid pixel detector

- IBM 3081

- Solid Logic Technology

References

[edit]- ^ E. J. Rymaszewski, J. L. Walsh, and G. W. Leehan, "Semiconductor Logic Technology in IBM", IBM Journal of Research and Development, 25, no. 5 (September 1981): 605.

- ^ "Filter Center". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Vol. 79, no. 13. September 23, 1963. p. 96.

- ^ Elenius, Peter; Levine, Lee (July 2000). "Comparing Flip-Chip and Wire-Bond Interconnection Technologies" (PDF). Chip Scale Review. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-10-23. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ^ "BGA Underfill for COTS Ruggedization". NASA. 2019.

- ^ "Underfill revisited: How a decades-old technique enables smaller, more durable PCBs". 2011.

- ^ Riley, George (November 2000). "Solder Bump Flip Chip". Flipchips.com. Archived from the original on 2014-10-16.

- ^ https://www.analog.com/media/en/technical-documentation/application-notes/AN-617.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Nandivada, Venkat (January 16, 2013). "Enhance Electronic Performance with Epoxy Compounds". Design World.

- ^ "The back-end process: Step 7 – Solder bumping step by step". Semiconductor Digest.

- ^ "Flip Chip—The Bumping Processes". Integrated Circuit Packaging, Assembly and Interconnections. Springer. 2007. pp. 143–167. doi:10.1007/0-387-33913-2_10. ISBN 978-0-387-28153-7.

- ^ Herbst, Wolfgang. "The back-end process: Step 5 – Flip chip attachProcess and material options". Semiconductor Digest. Retrieved 2024-08-24.

- ^ a b Lu, Daniel; Wong, C.P., eds. (18 November 2016). Materials for Advanced Packaging (Second ed.). Springer. p. 319. ISBN 978-3-319-45098-8.

- ^ He, Lei (2010). "System-in-Package: Electrical and Layout Perspectives". Foundations and Trends in Electronic Design Automation. 4 (4): 223–306. doi:10.1561/1000000014.

- ^ Demerjian, Charlie (2008-12-17), Nvidia chips show underfill problems, The Inquirer, archived from the original on July 21, 2009, retrieved 2009-01-30

- ^ Riley, George (October 2000). "Tutorial 1: Introduction to Flip Chip: What, Why, How". Flipchips.com. Archived from the original on 2009-01-30.

- ^ a b Lu, Daniel; Wong, C.P., eds. (17 December 2008). Materials for Advanced Packaging (First ed.). Springer. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-387-78219-5.

- ^ "Ajinomoto's 'secret ingredient' is now vital to chipmaking giants". 9 November 2022.

- ^ Li, Tengyu; Li, Peng; Sun, Rong; Yu, Shuhui (2023). "Polymer-based nanocomposites in semiconductor packaging". IET Nanodielectrics. 6 (3): 147–158. doi:10.1049/nde2.12050.

- ^ "ABF substrate shortages may dent 2021 shipments of new CPU, GPU chips". 14 December 2020.

External links

[edit]Flip chip

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Principles

Flip chip is a semiconductor packaging technique in which the active surface of a die is inverted and directly bonded to a substrate using interconnects such as solder bumps, allowing for high-density electrical connections and shorter signal pathways than wire-bonded alternatives.[6] In this method, the die—referring to the bare silicon chip containing the integrated circuit—is flipped so that its input/output (I/O) pads face downward toward the substrate, which serves as an intermediate carrier or printed circuit board providing routing to external connections.[1] The I/O pads are the metallized areas on the die's surface designed for electrical interfacing.[7] The core principle of flip chip relies on direct electrical interconnections formed by bumps, typically solder-based, that bridge the die and substrate with minimal interconnect length. These bumps, often 50-100 micrometers in diameter, are composed of materials such as eutectic Sn-Pb solder for traditional applications or lead-free alternatives like Sn-Ag-Cu alloys to comply with environmental regulations.[8][7] Copper pillars with solder caps represent an advanced variant, offering improved mechanical stability and finer pitch capabilities. Bump formation occurs through methods like electroplating, where solder is deposited via electrochemical processes; evaporation, involving vapor deposition of metal layers; or stud bumping, using wire bonding to create raised pillars.[6] To mitigate thermal stresses arising from coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) mismatches between the die and substrate, an underfill material—typically a capillary-flow epoxy—is dispensed between the bonded components, encapsulating the bumps and distributing mechanical loads.[9] This encapsulation enhances reliability by reducing shear forces on the interconnects during thermal cycling. Electrically, flip chip achieves superior performance through its short interconnect paths, which minimize inductance and capacitance compared to longer wire bonds, thereby supporting higher signal speeds and lower power losses in high-frequency applications.[10][11]Key Components and Materials

The flip chip assembly relies on several core components to achieve direct electrical and mechanical interconnections between the semiconductor die and the substrate. The semiconductor die, typically an integrated circuit (IC) or light-emitting diode (LED), serves as the active element and is oriented face-down to expose its bond pads for attachment. The substrate, often an organic laminate such as bismaleimide-triazine (BT) resin, FR-4, or ajinomoto build-up film (ABF) for cost-effective applications, or ceramic and silicon variants for enhanced thermal and electrical performance, acts as the base providing routing and support. Interconnects in the form of solder bumps or copper pillars bridge the die and substrate, enabling compact, high-I/O connections. Underfill epoxy, an epoxy-based resin with silica fillers, is introduced post-bonding to encapsulate these interconnects, offering mechanical reinforcement and improved thermal conductivity.[10] Solder bumps, the traditional interconnect choice, are fabricated from alloys tailored for reliability and process compatibility. Eutectic Sn-Pb solder, with a melting point of 183°C, was historically prevalent for its low processing temperatures and resistance to electromigration, but lead-free alloys like Sn-3.0Ag-0.5Cu (SAC305) have become standard, exhibiting melting points of 217-220°C to meet RoHS environmental regulations while maintaining joint integrity under thermal cycling. Copper pillars, an evolution for finer pitches under 100 μm, consist of electroplated copper with a thin solder cap, reducing electrical resistance and enhancing fatigue resistance in high-density configurations. Flux materials, typically no-clean formulations, are applied prior to reflow to remove surface oxides and promote wetting, ensuring void-free joints. Capping layers on the under-bump metallurgy (UBM), such as electroless nickel immersion gold (ENIG) with nickel and gold, protect against oxidation and intermetallic formation during storage and assembly.[10] Material compatibility is paramount, particularly in addressing thermal expansion differences that can induce stress. Silicon dies have a coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) of approximately 3 ppm/°C, contrasting sharply with organic substrates at 15-20 ppm/°C, which generates shear forces on interconnects during temperature excursions; underfill mitigates this by distributing stress and preventing delamination. For high-density interconnects in advanced applications, bump pitches below 50 μm are achieved with copper pillars, supporting fine-pitch demands while adhering to lead-free standards for sustainability and reliability against electromigration in prolonged operation.[10][12]Manufacturing Process

Bonding Techniques

Flip chip bonding techniques primarily involve attaching the active face of the semiconductor die to a substrate using specialized methods that ensure electrical connectivity and mechanical stability. The most widely adopted approach is solder reflow bonding, where pre-formed solder bumps on the die are aligned with substrate pads and heated to melt, allowing the molten solder to collapse and form reliable joints through self-alignment.[13] This process leverages surface tension for precise positioning, typically achieving alignments within 5-10 micrometers.[14] Thermocompression bonding serves as an alternative for non-solder connections, applying controlled heat and pressure to deform and bond metal bumps, such as gold studs, directly to substrate pads without melting.[15] This method is particularly suited for high-density applications requiring minimal thermal exposure.[16] For low-cost variants, adhesive bonding employs anisotropic conductive films (ACF) or pastes that provide both electrical conduction and mechanical adhesion under heat and pressure, enabling connections in flexible or organic substrates.[17][18] Alignment is a critical mechanic in all bonding techniques, achieved through fiducial marks on the die and substrate, captured by high-resolution vision systems for sub-micron precision placement.[19][20] In solder reflow, flux is applied to the bumps or pads via dipping, jetting, or brushing to remove oxides and promote wetting during melting.[21][13] Reflow profiles for lead-free solders, such as Sn-0.7Cu, involve a preheat ramp of 0.5-2.0°C/second, followed by a peak temperature of 250-260°C held above liquidus (227°C) for 60-90 seconds to ensure complete melting and joint formation without excessive intermetallic growth.[22][23] Thermocompression bonding, by contrast, uses localized heating to 300-400°C under 50-200 grams of force per bump, avoiding global reflow ovens.[24] Adhesive bonding typically cures at 150-200°C for 1-5 minutes, with pressure applied to embed conductive particles between electrodes.[25] Advanced variants enhance these techniques for finer pitches and higher performance. IBM's Controlled Collapse Chip Connection (C4) process, introduced in the 1960s, pioneered solder reflow by using high-lead bumps that collapse under controlled surface tension during reflow, enabling dense I/O connections up to 1000 per die.[1][13] For sub-100-micrometer pitches, copper pillar bumps with a solder cap combine the structural rigidity of electroplated copper posts (typically 30-50 micrometers tall) and a thin solder layer (5-20 micrometers) for reflow, reducing bridging risks and improving electromigration resistance compared to traditional solder bumps.[26][27] This structure maintains uniform standoff heights, facilitating underfill application in subsequent steps. A key challenge in solder-based bonding is void formation within joints, caused by trapped flux volatiles or outgassing during reflow, which can degrade thermal and electrical performance.[28] Mitigation strategies include optimizing reflow profiles to minimize time above liquidus and employing vacuum reflow, where negative pressure (10-100 Torr) extracts gases during the molten phase, reducing void percentages from over 20% to below 5%.[29][30] Low-residue, halide-free fluxes further limit voiding by volatilizing cleanly at temperatures below 200°C.[31]Assembly and Testing Steps

The assembly and testing of flip chip devices follow a structured sequence to ensure reliable interconnections and functionality, beginning with preparation of the die and substrate. Die preparation starts with bump fabrication on the wafer, where photolithography patterns the under-bump metallization (UBM) layers—typically consisting of adhesion, barrier, and wettable metals like Ti/Cu/Ni—on the die's I/O pads.[8] Electroplating then deposits solder (e.g., SnAg or SnPb alloys) into the patterned openings, followed by a reflow step to form spherical bumps with heights around 70-100 µm.[32] The wafer is then diced into individual dies. Substrate preparation involves metallizing the bonding pads, often applying UBM layers similar to those on the die to enhance solder wetting and prevent diffusion, ensuring compatibility with the substrate material such as organic laminates or ceramics.[33] The die is subsequently flipped and aligned onto the substrate using high-precision pick-and-place equipment, achieving placement accuracy of ±9 to 12 µm at ±3σ to match bumps with pads.[34] Bonding occurs via reflow soldering in a nitrogen atmosphere, where the assembly is heated to melt the solder bumps, allowing controlled collapse and formation of reliable joints; alternatively, compression bonding applies force for non-solder interconnects like conductive adhesives.[34] Flux is applied prior to placement to clean surfaces and promote wetting, with options including dip fluxing or dispensing low-viscosity formulations.[34] Following bonding, underfill—a low-viscosity epoxy—is dispensed along the die edges to flow via capillary action into the gap (typically 50-100 µm), encapsulating the interconnects for mechanical support and to mitigate thermal expansion mismatch between die and substrate.[35] The underfill is then cured at 150-165°C for 60-120 minutes using convection oven to achieve a void-free fillet covering at least 70% of the die height.[35] For enhanced heat dissipation, a lid (e.g., copper or aluminum) is attached to the die backside using a thermal interface material like silicone grease or phase-change pads, improving thermal resistance by spreading heat across the package.[36] As of 2025, emerging manufacturing techniques include panel-level fan-out wafer-level packaging (FOPLP), which extends wafer-scale processing to larger panels for improved yield and cost efficiency in high-volume production, and hybrid Cu-Cu bonding for pitches below 10 µm, enabling denser interconnections without solder.[37] Testing procedures verify electrical, mechanical, and thermal integrity post-assembly. Electrical testing employs flying probe systems to check continuity, opens, and shorts across the interconnects without fixed fixtures, suitable for low-to-medium volumes and achieving test coverage for I/O nets.[38] Non-destructive X-ray inspection detects voids in underfill or solder joints, ensuring no defects larger than 25% of joint area that could compromise reliability.[39] Reliability assessment includes thermal cycling per JEDEC JESD22-A104 standards, subjecting assemblies to -40°C to 125°C for up to 1000 cycles to simulate operational stresses and evaluate solder joint fatigue. Yield considerations are critical, with mature flip chip processes achieving defect rates below 1% through optimized parameters like flux tackiness and placement accuracy, enabling overall yields exceeding 99% in high-volume production.[40] Rework methods, such as hot gas desoldering to remove faulty dies followed by site cleaning (e.g., via vacuum or abrasive brushing), allow recovery of substrates and improve final yield, particularly for underfilled assemblies.[41] For scaling to volume manufacturing, integration with wafer-level processing—such as fan-out wafer-level packaging (FOWLP)—performs bumping and redistribution at the wafer scale before singulation, potentially lowering overall production costs through wafer-scale efficiency.[42]Comparisons and Trade-offs

Versus Wire Bonding

Wire bonding is a widely used interconnection method in semiconductor packaging that employs thin wires, typically gold or aluminum with diameters of 25-50 μm, to connect the pads on a semiconductor die to the leads or pads on a substrate or package. These wires are attached using thermosonic bonding for gold (involving heat, pressure, and ultrasonic vibration at 150-200°C) or ultrasonic wedge bonding for aluminum (at 125-150°C with ultrasonic energy), forming reliable metallurgical bonds in a looped configuration.[43][44] In terms of structure, flip chip differs fundamentally from wire bonding by using direct solder or conductive bump attachments in an area array configuration on the active side of the die, which is flipped and aligned to matching pads on the substrate, eliminating the need for wire loops. Wire bonding, by contrast, relies on peripheral pad arrangements and arched wire spans typically 1-5 mm in length, which introduce longer electrical paths and higher parasitic inductance compared to the sub-millimeter bump heights in flip chip (often 50-100 μm). This structural variance results in flip chip providing significantly lower inductance—often by factors of 5-10 times—due to minimized loop areas and shorter interconnect distances.[43][45] Performance-wise, flip chip supports substantially higher input/output (I/O) density, enabling up to 10 times more connections per unit area (e.g., over 5,000 bumps at 200 μm pitch versus wire bonding's practical limit of 500-600 peripheral I/Os), which facilitates superior signal integrity and power delivery in dense designs. Flip chip also excels in high-speed applications, supporting frequencies in the multi-GHz range (e.g., 10-40 GHz) with reduced signal delay and crosstalk, whereas wire bonding is generally constrained to lower frequencies (typically up to 2-3 GHz for RF applications) due to elevated inductance and capacitance from the wire loops, limiting its use in MHz-to-low-GHz scenarios without compensation techniques.[43][46][47] Regarding suitability, wire bonding remains ideal for cost-sensitive, low-to-moderate density packages and discrete components where I/O counts are below 600 and production volumes are high, leveraging its established infrastructure and yields over 99%. Flip chip, however, is preferred for high-performance integrated circuits like microprocessors and RF devices requiring dense I/O and fast signaling, though it demands more precise alignment and underfill processes.[43][44]Versus Tape-Automated Bonding

Tape-automated bonding (TAB) is an interconnection technique that employs a flexible polyimide tape embedded with patterned copper leads, which are bonded to the chip's contact pads via inner lead bonding and subsequently to the substrate through outer lead bonding, enabling automated reel-to-reel assembly.[48] This method contrasts with flip chip bonding, where the die is inverted and connected directly to the substrate using an array of solder or conductive bumps distributed across the entire chip surface, allowing for simultaneous formation of all interconnections.[49] A key difference lies in their interconnection layouts: flip chip utilizes an area-array configuration that supports thousands of input/output (I/O) connections by leveraging the full die area, whereas TAB relies on peripheral leads along the chip edges, typically limiting I/O counts to 200–500 per die.[50] This peripheral approach in TAB provides higher lead density than wire bonding but falls short of flip chip's capacity for high-density arrays, making TAB more suitable for moderate I/O requirements.[48] In terms of performance, flip chip excels in electrical characteristics due to shorter interconnect lengths, lower inductance, and better suitability for high-frequency signals and 3D stacking in miniaturized packages, though it involves higher upfront manufacturing costs from bump formation and underfill processes.[49] TAB, while offering good flexibility and low-profile assembly for applications like displays, incurs elevated costs for high-density setups due to specialized tooling and tape preparation, and it provides superior pre-assembly testability compared to flip chip.[50] Overall, flip chip is preferred for advanced miniaturization and performance-driven scenarios, whereas TAB's automation advantages shine in volume production of flexible interconnects.[48] Regarding applications, TAB is commonly employed in LCD driver circuits, where its tape-based flexibility facilitates connections between driver chips and glass substrates in flat-panel displays.[51] In contrast, flip chip is integral to system-in-package (SiP) technologies, enabling the integration of multiple dies in compact, high-performance modules for electronics like mobile devices and sensors.[52]Advantages

Flip chip technology provides significant performance benefits through enhanced electrical efficiency and superior signal integrity. The direct interconnection via solder bumps results in very low resistance, typically 5-20 mΩ per bump, minimizing power losses and enabling efficient current flow in high-power applications.[53] Additionally, the short interconnect paths reduce parasitic inductance to below 0.5 nH, which improves overall electrical performance by decreasing signal delay and electromagnetic interference.[2] For high-frequency operations, flip chip excels in maintaining signal integrity, supporting bandwidths up to 100 GHz with minimal degradation due to reduced capacitance and inductance effects.[54] In terms of integration advantages, flip chip facilitates the creation of multi-chip modules and 3D integrated circuits by allowing dense stacking of dies with high I/O counts. This approach enables heterogeneous integration of multiple chips in a compact assembly, promoting advanced system-on-chip designs without excessive overhead.[55] The resulting smaller form factors closely match the die size itself, with minimal additional packaging volume, which is essential for space-constrained electronics.[56] Flip chip also offers strong reliability and scalability through improved thermal dissipation and cost-effectiveness in production. Direct bump attachment provides efficient heat paths from the die to the substrate, enhancing thermal management and supporting reliable operation in demanding environments.[55] For scalability, the technology is particularly advantageous in high-volume manufacturing, such as consumer electronics, where automated processes reduce assembly costs and enable rapid scaling for billions of units annually.[57] From an environmental perspective, flip chip supports the use of lead-free solders, such as tin-based alloys, to meet regulatory compliance for hazardous substance restrictions while maintaining joint integrity.[58]Disadvantages

One major technical challenge in flip chip assembly is the coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) mismatch between the silicon die and the organic substrate, which induces significant thermal stresses leading to warpage or cracks during temperature cycling, with von Mises stresses in solder joints reaching up to approximately 46 MPa at critical locations.[59] Underfill voids, often resulting from incomplete flow or trapped air during encapsulation, compromise mechanical integrity and accelerate fatigue failure, potentially reducing the mean time to failure (MTTF) of solder joints by factors of up to 2 in accelerated thermal tests.[60] Economically, flip chip requires substantial upfront investment in wafer bumping equipment and processes, with production lines costing several million dollars—far higher than the simpler tooling for wire bonding—making it less viable for low-volume production.[61] Additionally, early-stage assembly yields for flip chip can be lower than those for mature wire bonding processes due to sensitivities in bumping and reflow, thereby increasing overall manufacturing costs through higher defect rates.[62] However, advancements as of 2025, including improved underfill materials and automated rework systems, have mitigated some yield and rework challenges. The process demands high precision in die-to-substrate alignment, typically requiring accuracies better than 5 μm to ensure reliable bump contacts, which complicates automation and raises equipment demands.[63] Reworking underfilled flip chips is particularly difficult, as removing the die without damaging the substrate or adjacent components often leads to elevated scrap rates in complex assemblies.[41] Flip chip is not ideal for applications with very low input/output (I/O) counts, where the added complexity and cost outweigh benefits compared to simpler wire bonding, nor for non-planar mounting surfaces, as it requires highly flat substrates to avoid misalignment and stress concentrations.Historical Development

Origins and Invention

The origins of flip chip technology trace back to the late 1950s and early 1960s, when engineers sought compact, high-reliability packaging for military applications, including radar systems. Early concepts involved solder bumps for direct interconnection of semiconductor devices to substrates, addressing limitations in wire bonding such as poor density and signal integrity in harsh environments. These precursors emerged in military radar packaging efforts, where space constraints and vibration resistance demanded innovative approaches to mounting active components. By 1960, General Electric's Light Military Electronics Department in Utica, New York, advanced the idea with a flip chip assembly method described as a thin-film approach to single-crystal logic operators, enabling face-down attachment of silicon chips to ceramic substrates via solder bumps for improved thermal and electrical performance. The foundational invention of the modern flip chip process occurred at IBM in 1962, credited to engineer Paul A. Totta, who demonstrated a glass-passivated silicon transistor with solder bump connections during that summer. This work evolved into IBM's Controlled Collapse Chip Connection (C4) process, where high-lead solder bumps on the chip collapse controllably during reflow soldering to form precise, reliable joints to a substrate. The C4 technique was initially developed for mainframe computers, with the process first detailed in technical literature by 1964 and published in detail in 1969. Totta's innovation built on prior bump ideas but introduced passivation and controlled reflow to prevent bridging and ensure alignment, marking a shift from experimental military concepts to scalable commercial production.[64] The primary motivation for flip chip development at IBM was the demand for higher interconnection density in Solid Logic Technology (SLT) modules, which replaced cumbersome wire bonding in the transition from vacuum tube systems to transistor-based computing. Wire bonding restricted input/output (I/O) counts to around 10-20 per device, leading to excessive inductance, larger footprints, and reliability issues in high-speed circuits. SLT flip chips allowed multiple I/O pads across the chip face, enabling denser module designs for mainframe logic while improving signal speed and heat dissipation—critical for the era's push toward integrated electronics. This addressed the packaging bottlenecks in scaling transistor counts, directly supporting IBM's goal of reliable, high-performance systems amid the semiconductor revolution.[65] Flip chip saw its first major implementation in the 1965 IBM System/360 mainframe, where SLT chips with approximately 12 I/O pads per device were flip-chip mounted onto multilayer ceramic substrates, achieving up to 100 I/Os across assembled modules. These early chips, typically housing 3-4 logic circuits, used 100-micron-pitch bumps to connect transistors and diodes, enabling the System/360's modular architecture and contributing to its commercial success with millions of units produced. Influences from pioneers like Robert N. Noyce at Fairchild Semiconductor, whose 1959 integrated circuit patent spurred industry-wide miniaturization, underscored the broader need for advanced packaging to match IC density gains.[66][67]Milestones and Adoption

The commercialization of flip chip technology accelerated in the 1970s and 1980s, transitioning from specialized applications in mainframe computers to broader use in consumer electronics, driven by advancements in solder bumping and underfill materials that addressed thermal fatigue issues.[67] By the late 1980s, underfill epoxies significantly improved reliability for organic substrates, enabling initial adoption in portable devices like pagers.[68] This period marked the shift from IBM's early ceramic-based implementations to more cost-effective laminate substrates, laying the groundwork for mass production. The 1990s saw a boom in flip chip adoption, fueled by the need for higher I/O density in compact electronics and the development of lead-free solder alternatives to meet emerging environmental regulations.[22] Research into alloys like Sn-3.5Ag and Sn-0.7Cu began in the mid-1990s, providing viable options for flip chip interconnects with comparable mechanical performance to traditional Sn-Pb solders.[69] Mobile phones exemplified this trend, with Motorola's 1993 Flip Chip on Board (FCOB) in pen pagers and 1996 StarTac handset achieving over 500 million units produced globally, demonstrating reliability in high-volume consumer products.[68] Graphics processing units (GPUs) also began incorporating flip chip for improved thermal management and performance, as seen in early high-end designs from the late 1990s.[8] From the 2000s onward, flip chip integrated deeply with Ball Grid Array (BGA) packaging, evolving from ceramic to organic substrates to reduce costs and leverage existing PCB infrastructure, which became standard for microprocessors and system-on-chips. This integration supported finer pitches and higher bump counts, essential for scaling with Moore's Law, where transistor density doubling every two years necessitated advanced interconnects to handle increased I/O without compromising signal integrity.[70] In the 2020s, flip chip has driven trends in 5G and AI applications, with Apple's A-series processors utilizing thousands of micro-bumps for high-bandwidth connections in integrated fan-out (InFO) packages produced by TSMC.[71] By 2025, TSMC's InFO and CoWoS technologies have further advanced flip chip integration for AI and high-performance computing applications, including in Apple's M-series processors.[72] Standards like IPC-7095 have facilitated this by providing guidelines for BGA design, assembly, and inspection, including considerations for flip chip terminations and lead-free processes.[73] Global adoption has shifted from U.S.-centric pioneers like IBM, which dominated early development, to Asia-based foundries such as TSMC and Samsung, which now handle the majority of high-volume manufacturing due to their advanced wafer bumping and packaging capabilities.[74] This transition, accelerated in the 2000s by outsourcing trends and investments in 300mm fabs, has enabled cost efficiencies and scaled production for AI and 5G chips.Applications and Alternatives

Primary Uses in Electronics

Flip chip technology is widely employed in high-performance computing applications, particularly in microprocessors where dense interconnects are essential. For instance, Intel has utilized flip chip packaging in its CPU designs since the late 1990s, enabling ball grid array (BGA) configurations that support over 2,000 input/output (I/O) connections for enhanced signal integrity and thermal management in processors like those in the Core series.[75] Similarly, AMD incorporates flip chip BGA in its Ryzen and EPYC CPU architectures, facilitating high I/O densities exceeding 2,000 pins in server-grade packages to handle complex workloads in data centers.[76] In memory applications, flip chip enables efficient stacking of dies, such as in 3D-integrated DRAM modules where logic chips are paired with memory stacks, improving bandwidth and reducing latency in systems like high-speed caches.[77] In consumer electronics, flip chip is integral to system-on-chip (SoC) designs in smartphones, providing compact, high-speed interconnections for multimedia and AI processing. Qualcomm's Snapdragon processors, including models like the Snapdragon 888 and earlier 600 series, employ flip chip BGA packaging to integrate modem, GPU, and CPU components on a single die, supporting 5G connectivity and power efficiency in devices from major manufacturers.[78][79] For displays, flip chip bonding is used in OLED driver circuits, allowing precise attachment of silicon backplanes to flexible substrates for high-resolution screens in smartphones and wearables, which enhances image quality and reduces power consumption.[65] The automotive and aerospace sectors leverage flip chip for its reliability in harsh environments, particularly in sensors and electronic control units (ECUs) that demand robust thermal and mechanical performance. In advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS), flip chip packaging is applied to chips processing radar, lidar, and camera data, as seen in ECUs from automotive suppliers, where it ensures high I/O density and vibration resistance for real-time decision-making in vehicles.[80][81] Aerospace applications similarly use flip chip in avionics sensors for fault-tolerant operations under extreme temperatures and radiation.[82] Emerging uses of flip chip extend to LEDs and photonics for high-power applications, as well as medical devices requiring miniaturization. In high-brightness LEDs, flip chip designs eliminate wire bonds to improve heat dissipation and light output, enabling efficient modules for automotive lighting and general illumination.[83] Photonics benefits from flip chip in hybrid integration of lasers and detectors on submounts, supporting compact optical transceivers for data centers.[84] For implantable medical ICs, flip chip facilitates biocompatible packaging in devices like neural stimulators, allowing direct bonding to flexible substrates for reduced size and improved longevity in body-compatible electronics.[85] Market data indicates flip chip's growing dominance in advanced packaging, with the segment holding approximately 38% share in 2024 and projected to expand significantly by 2030 due to demand in AI and 5G applications.[86] The global flip chip market is valued at USD 35.51 billion in 2025, expected to reach USD 50.97 billion by 2030 at a CAGR of 7.49%, reflecting its critical role in electronics evolution.[87]Alternative Technologies

Wire bonding remains the dominant interconnection technology in semiconductor packaging, particularly for cost-sensitive and low-density applications such as sensors and legacy devices, where it accounts for approximately 52.5% of overall market shipments in traditional packaging formats.[88] This method excels in scenarios requiring simple, reliable connections without the need for high I/O counts, offering lower material and processing costs compared to more advanced techniques. Its widespread adoption stems from decades of maturity, enabling high-volume production in consumer electronics and automotive components where performance demands are moderate.[89] Tape-automated bonding (TAB) serves as an alternative for applications demanding flexible interconnects, such as wearables and flat-panel displays, where its use of polyimide tape allows for bending radii not feasible with rigid substrates.[90] Although TAB's overall market presence has declined due to the rise of flip chip and wafer-level methods, it persists in niche high-flexibility needs, providing fine-pitch connections up to 50 μm and supporting reel-to-reel automation for efficient assembly.[91] TAB is particularly suited for liquid crystal displays (LCDs) and flexible printed circuits, where mechanical compliance is critical.[92] For 3D stacking applications that extend beyond standard flip chip capabilities, through-silicon vias (TSVs) enable vertical integration by creating conductive paths through the silicon die, facilitating shorter interconnects and higher bandwidth in stacked memory and logic configurations.[93] TSVs are ideal for high-performance computing where flip chip alone cannot achieve the density required for multi-die stacks, reducing latency and power consumption by up to 50% in some designs.[94] Complementing this, fan-out wafer-level packaging (FOWLP) supports heterogeneous integration by redistributing I/Os beyond the die footprint on a molded wafer, allowing the co-packaging of diverse chips like processors and sensors without substrates.[95] FOWLP is increasingly used in mobile and AI devices for its substrate-less approach, enabling finer pitches down to 40 μm and improved thermal management.[96] Hybrid approaches often combine flip chip with silicon interposers in 2.5D packaging, where the interposer provides high-density routing between dies, as seen in graphics processing units (GPUs) that integrate high-bandwidth memory (HBM) alongside the core die.[97] This configuration leverages flip chip bumps for attachment while the interposer handles micro-vias and redistribution layers, achieving interconnect densities exceeding 1,000 I/Os per mm² for AI and data center applications.[98] Looking ahead, emerging trends point to wire embedding techniques, which integrate wires directly into substrates or molds for denser, more reliable connections in multi-chip modules, potentially surpassing traditional bonding in high-volume embedded systems.[99] Similarly, photonics interconnects, utilizing optical signals via waveguides and silicon photonics platforms, are positioned as replacements for electrical links in ultra-high-density scenarios, offering bandwidths over 1 Tbps with lower energy per bit for future exascale computing.[100]References

- https://en.wikichip.org/wiki/Flip_Chip_Ball_Grid_Array