Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

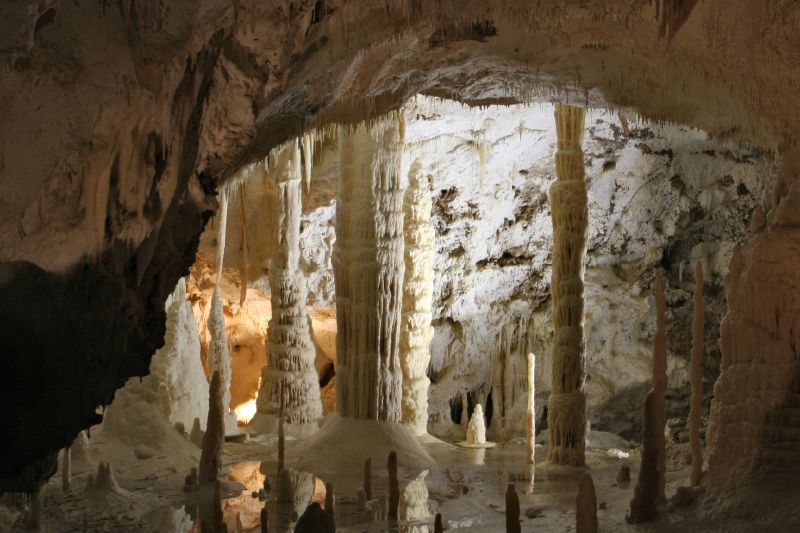

Frasassi Caves

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

The Frasassi Caves (Italian: Grotte di Frasassi) are a karst cave system in the municipality of Genga, Italy, in the province of Ancona, Marche. They are among the most famous show caves in Italy.

History

[edit]An entrance to one of the Frasassi caves was discovered by a farmer on June 28, 1948. More entrances were found in the 1950s and 1960s by members of the Italian Mountaineering Club (Club Alpino Italiano) from the nearby towns of Jesi and Fabriano. In the 70’s more caves where discovered by a group of Ancona speleologists led by Giancarlo Cappanera on 25 September 1971,[2] are situated 7 kilometres (4 miles) south of Genga, near the civil parish of San Vittore and the Genga-San Vittore railway station (Rome–Ancona railway). Rich in water, the cave system is particularly well endowed with stalactites and stalagmites.[3]

Near the entrance to the caves are two sanctuary-chapels: one is the 1029 Santuario di Santa Maria infra Saxa (Sanctuary of Holy Mary under the Rock) and the second is an 1828 Neoclassical architecture formal temple, known as Tempietto del Valadier.

Chambers

[edit]The Frasassi cave system includes a number of named chambers, including the following:

- Grotta delle Nottole, or "Cave of the Bats", named for the large colony of bats that lives within.[3]

- Grotta Grande del Vento, or "Great Cave of the Wind", discovered in 1971, with approximately 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) of passageways.[3]

- Abisso Ancona, or "Ancona Abyss", a huge space around 180 x 120 meters wide and near 200m tall.[3]

- Sala delle Candeline, or "Room of the Candles", named for its plentiful stalagmites that resemble candles.[3]

- Sala dell'Infinito, or "Room of the Infinite", a tall chamber with massive speleothem columns supporting the roof.[3]

-

"Organ pipes"

-

Water well

Scientific experiments

[edit]The cave has been used to conduct experiments in chronobiology. Among the cavers that have spent considerable amount of time inside the cave is the Italian sociologist Maurizio Montalbini. In 1986, he ventured into the Grotte di Frasassi beneath Italy's Apennine mountains. He survived on pills, powders, and other astronaut-like food while researchers monitored his health. His few luxuries were chocolate, honey, and plenty of tobacco, smoking nearly two packs of cigarettes a day. During his time underground, away from sunlight, Mr. Montalbini lost almost 30 pounds. He would stay awake for 50 hours at a stretch, then sleep for five. He spent his time reading and writing a novel titled "Where the Sun Sleeps." He reported enjoying his underground experience, aside from the occasional earthquakes."One cannot fight solitude, one must make a friend of it," he remarked after emerging 210 days later, although he believed it had only been 79 days.[4] He died in 2009.[5]

Penn State Research

[edit]Penn State researchers, led by Professor Jennifer Macalady, a microbiologist, studies microbial biofilms in some of the planet's most hostile environments to understand the limits of life and how life started on Earth. Macalady, along with doctoral student Dani Buchheister, explored Italy's Frasassi cave system, sampling biofilms, referred to as "alien cave goo" due to its stringy dark nature, from underground lakes, including Lago Verde. Their research, featured in the December 2023 issue of National Geographic,[6] sought to uncover how microbes survive in extreme conditions without sunlight or oxygen, akin to early Earth. Key findings included that microbes can survive with minimal resources such as rocks and water, and that these biofilms may reflect the first metabolic processes on Earth.[7]

Sister caves

[edit]Frasassi is partnered with several sister caves[8] around the world:

See also

[edit]- List of caves

- List of caves in Italy

- Bochnia Salt Mine, southern Poland, central Europe

- Wieliczka Salt Mine, near Kraków in Poland, central Europe

- Khewra Salt Mine, in Punjab, Pakistan

- Kartchner Caverns State Park in Arizona, the United States

- Grand Roc in Savoie, France, southern Europe

- Salt Cathedral of Zipaquirá, in Zipaquirá, Cundinamarca, Colombia, South America

- Chełm Chalk Tunnels, Poland, central Europe

References

[edit]- ^ (in Italian) History of Frasassi

- ^ "Come fu scoperta la Grotta Grande del Vento di Frasassi". frasassigsm.it (in Italian).

- ^ a b c d e f Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. p. 149. ISBN 0-89577-087-3.

- ^ Miller, Stephen (September 22, 2009). "He Traded Company for Caves to Study Effects of Isolation".

- ^ "Maurizio Montalbini". The Telegraph. 2009-09-21. Retrieved 2024-07-24.

- ^ "NASA is preparing to explore alien worlds—by investigating Earth's dark corners". Premium. 2024-07-24. Retrieved 2024-07-24.

- ^ "Q&A: Searching for life where it shouldn't exist | Penn State University". www.psu.edu. Retrieved 2024-07-24.

- ^ Sister caves on frasassi.com Archived 2009-08-31 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- (in Italian and English) Grotte di Frasassi official site

- (in English) The story of the discovery of the Frasassi caves

- (in Italian) Frasassi Online