Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Frontal process of maxilla

View on Wikipedia| Frontal process of maxilla | |

|---|---|

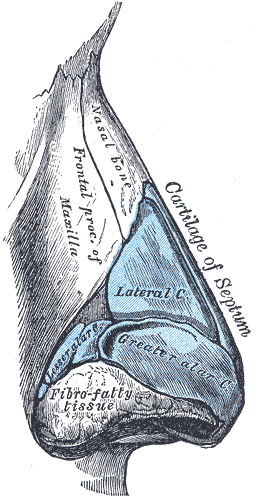

Cartilages of the nose. Side view. (Frontal process of maxilla visible at center.) | |

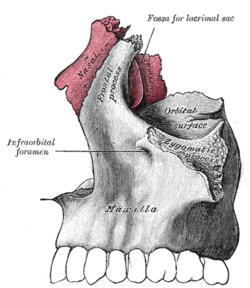

Articulation of nasal and lacrimal bones with maxilla. (Frontal process visible at top center.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | processus frontalis maxillae |

| TA98 | A02.1.12.024 A02.1.14.006 |

| TA2 | 781 |

| FMA | 52894 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The frontal process of the maxilla is a strong plate, which projects upward, medialward, and backward from the maxilla, forming part of the lateral boundary of the nose.

Its lateral surface is smooth, continuous with the anterior surface of the body, and gives attachment to the quadratus labii superioris, the orbicularis oculi, and the medial palpebral ligament.

Its medial surface forms part of the lateral wall of the nasal cavity; at its upper part is a rough, uneven area, which articulates with the ethmoid, closing in the anterior ethmoidal cells; below this is an oblique ridge, the ethmoidal crest, the posterior end of which articulates with the middle nasal concha, while the anterior part is termed the agger nasi; the crest forms the upper limit of the atrium of the middle meatus.

The upper border articulates with the frontal bone and the anterior with the nasal; the posterior border is thick, and hollowed into a groove, which is continuous below with the lacrimal groove on the nasal surface of the body: by the articulation of the medial margin of the groove with the anterior border of the lacrimal a corresponding groove on the lacrimal is brought into continuity, and together they form the lacrimal fossa for the lodgement of the lacrimal sac.

The lateral margin of the groove is named the anterior lacrimal crest, and is continuous below with the orbital margin; at its junction with the orbital surface is a small tubercle, the lacrimal tubercle, which serves as a guide to the position of the lacrimal sac.

Additional images

[edit]-

Frontal process shown in red. Animation.

-

Left and right frontal process of maxilla, and upper teeth. Animation.

-

Articulation of left palatine bone with maxilla.

-

The skull from the front.

-

Sagittal section of skull.

-

Roof, floor, and lateral wall of left nasal cavity.

-

Frontal process of maxilla

-

Frontal process of maxilla

External links

[edit]- Anatomy photo:22:os-1903 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Osteology of the Skull: The Maxilla"

- "Anatomy diagram: 34256.000-1". Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 2012-12-27.