Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Premaxilla

View on Wikipedia| Premaxilla | |

|---|---|

Skull of Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, premaxilla in orange | |

Human premaxilla and its sutures | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Median nasal prominence |

| Identifiers | |

| TA98 | A02.1.12.031 |

| TA2 | 833 |

| FMA | 77231 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals has been usually termed as the incisive bone. Other terms used for this structure include premaxillary bone or os premaxillare, intermaxillary bone or os intermaxillare, and Goethe's bone.

Human anatomy

[edit]| Incisive bone | |

|---|---|

The bony palate and alveolar arch. (Premaxilla is not labeled, but region is visible.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os incisivum |

| TA98 | A02.1.12.031 |

| TA2 | 833 |

| FMA | 77231 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

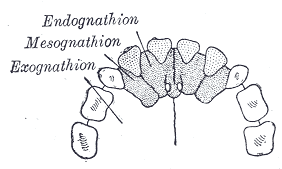

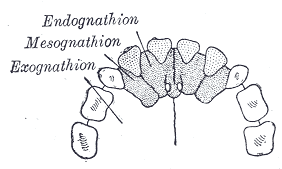

In human anatomy, the premaxilla is referred to as the incisive bone (os incisivum) and is the part of the maxilla which bears the incisor teeth, and encompasses the anterior nasal spine and alar region. In the nasal cavity, the premaxillary element projects higher than the maxillary element behind. The palatal portion of the premaxilla is a bony plate with a generally transverse orientation. The incisive foramen is bound anteriorly and laterally by the premaxilla and posteriorly by the palatine process of the maxilla. [1]

It is formed from the fusion of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the jaws of many animals, usually bearing teeth, but not always. They are connected to the maxilla and the nasals. While Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was not the first one to discover the incisive bone in humans, he was the first to prove its presence across mammals. Hence, the incisive bone is also known as Goethe's bone.[2]

Incisive bone and premaxilla

[edit]Incisive bone is a term used for mammals, and it has been generally thought to be homologous to premaxilla in non-mammalian animals. However, there are counterarguments. According to them, the incisive bone is a novel character first acquired in therian mammals as a composition of premaxilla derived from medial nasal prominence and septomaxilla derived from maxillary prominence. In the incisive bones, only the palatine process corresponds to the premaxilla, while the other parts are the septomaxilla. Based on this, the incisive bone is not completely homologous to the non-mammalian premaxilla. This was hypothesized by Ernst Gaupp in 1905[3] and demonstrated by developmental biological- and paleontological experiments in 2021.[4] This issue is still under debate.

Embryology

[edit]In the embryo, the nasal region develops from neural crest cells which start their migration down to the face during the fourth week of gestation. A pair of symmetrical nasal placodes (thickenings in the epithelium) are each divided into medial and lateral processes by the nasal pits. The medial processes become the septum, philtrum, and premaxilla.[5]

The first ossification centers in the area of the future premaxilla appear during the seventh week above the germ of the second incisor on the outer surface of the nasal capsule. After eleven weeks an accessory ossification center develops into the alar region of the premaxilla. Then a premaxillary process grow upwards to fuse with the frontal process of the maxilla; and later expands posteriorly to fuse with the alveolar process of the maxilla. The boundary between the premaxilla and the maxilla remains discernible after birth and a suture is often observable up to five years of age. [1]

It is also common in non-mammals, such as chickens, that premaxilla is derived from medial nasal prominence. However, experiments using mice have shown a different result. The bone that has been called the "premaxilla" (incisive bone) in mice consists of two parts: most of the bone covering the face originates from the maxillary prominence, and only a part of the palate originates from the medial nasal prominence.[4] This may be due to the replacement of most of the incisive bone with septomaxilla in the therian mammal, as following section. In any case, the development and evolution of this region is complex and needs to be considered carefully.

In bilateral cleft lip and palate, the growth pattern of the premaxilla differs significantly from the normal case; in utero growth is excessive and directed more horizontally, resulting in a protrusive premaxilla at birth.[6]

Evolutionary variation

[edit]Forming the oral edge of the upper jaw in most jawed vertebrates, the premaxillary bones comprise only the central part in more primitive forms. They are fused in blowfishes and absent in cartilaginous fishes such as sturgeons.[7]

Reptiles and most non-mammalian therapsids have a large, paired, intramembranous bone behind the premaxilla called the septomaxilla. Because this bone is vestigial in Acristatherium (a Cretaceous eutherian) this species is believed to be the oldest known therian mammal. Intriguingly the septomaxilla is still present in monotremes.[8][9]

However, embryonic and fossil studies in 2021 suggest that the incisive bone, which has been called "premaxilla" in therian mammals, has been largely replaced by septomaxilla; and that only a palatal part of the incisive bone remains a vestige of premaxilla.[4] If this hypothesis is accurate, the bones that have been called "premaxilla" in therian mammals are not entirely homologous to the original premaxilla of other vertebrates. This homology is, however, contended.[10]

The differences in the size and composition in the premaxilla of various families of bats is used for classification.[11]

The premaxillae of squamates are fused; this feature can be used to distinguish fossil squamates from relatives.[12]

History

[edit]In 1573, Volcher Coiter was the first to illustrate the incisive suture in humans. Pierre Marie Auguste Broussonet and Félix Vicq-d'Azyr were the first to describe the incisive bone as a separate bone within the skull in 1779 and 1780, respectively.[2]

In the 1790s, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe began studying zoology, and formed the impression that all animals are similar, being bodies composed of vertebrae and their permutations. The human skull is one example of a metamorphosed vertebra, and within it, the intermaxillary bone rests as evidence linking the species to other animals.[13]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Lang, Johannes (1995). Clinical anatomy of the masticatory apparatus peripharyngeal spaces. Thieme. ISBN 978-3-13-799101-4.

- ^ a b Barteczko, K; Jacob, M (March 2004). "A re-evaluation of the premaxillary bone in humans". Anatomy and Embryology. 207 (6): 417–437. doi:10.1007/s00429-003-0366-x. PMID 14760532. S2CID 13069026.

- ^ Gaupp, E. (1905). "Neue Deutungen auf dem Gebiete der Lehre vom Säugetierschädel". Anat. Anz. 27: 273–310.

- ^ a b c Higashiyama, Hiroki; Koyabu, Daisuke; Hirasawa, Tatsuya; Werneburg, Ingmar; Kuratani, Shigeru; Kurihara, Hiroki (November 2, 2021). "Mammalian face as an evolutionary novelty". PNAS. 118 (44) e2111876118. Bibcode:2021PNAS..11811876H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2111876118. PMC 8673075. PMID 34716275.

- ^ "Nasal Anatomy". Medscape. June 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Vergervik, Karin (1983). "Growth Characteristics of the Premaxilla and Orthodontic Treatment Principles in Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate" (PDF). Cleft Palate Journal. 20 (4). Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Premaxilla". ZipCodeZoo. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Hu, Yaoming; Meng, Jin; Li, Chuankui; Wang, Yuanqing (January 22, 2010). "New basal eutherian mammal from the Early Cretaceous Jehol biota, Liaoning, China". Proc Biol Sci. 277 (1679): 229–236. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0203. PMC 2842663. PMID 19419990.

- ^ Wible, John R.; Miao, Desui; Hopson, James A. (March 1990). "The septomaxilla of fossil and recent synapsids and the problem of the septomaxilla of monotremes and armadillos". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 98 (3): 203–228. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1990.tb01207.x.

- ^ Wible, John R. (March 2022). "The history and homology of the os paradoxum or dumb-bell-shaped bone of the platypus Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Mammalia, Monotremata)". Vertebrate Zoology. 72: 143–158. doi:10.3897/vz.72.e80508.

- ^ Myers, P.; Espinosa, R.; Parr, C. S.; Jones, T.; Hammond, G. S.; Dewey, T. A. (2006). "Premaxillae of bats". Animal Diversity Web. Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ Brownstein, Chase D.; Meyer, Dalton L.; Fabbri, Matteo; Bhullar, Bhart-Anjan S.; Gauthier, Jacques A. (2022-11-29). "Evolutionary origins of the prolonged extant squamate radiation". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 7087. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.7087B. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34217-5. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9708687. PMID 36446761.

- ^ Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1960). The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 194. ISBN 0-691-02350-6.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)