Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nasal bone

View on Wikipedia

| Nasal bone | |

|---|---|

Nasal bone visible at center, in dark green. | |

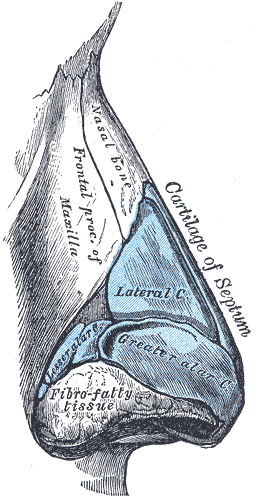

Cartilages of the nose. Side view. (Nasal bone visible at upper left.) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os nasale |

| MeSH | D009295 |

| TA98 | A02.1.10.001 |

| TA2 | 748 |

| FMA | 52745 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Each has two surfaces and four borders.

Structure

[edit]There is heavy variation in the structure of the nasal bones, accounting for the differences in sizes and shapes of the nose seen across different people. Angles, shapes, and configurations of both the bone and cartilage are heavily varied between individuals. Broadly, most nasal bones can be categorized as "V-shaped" or "S-shaped" but these are not scientific or medical categorizations. When viewing anatomical drawings of these bones, consider that they are unlikely to be accurate for a majority of people.[1]

The two nasal bones are joined at the midline internasal suture and make up the bridge of the nose.

Surfaces

[edit]The outer surface is concavo-convex from above downward, convex from side to side; it is covered by the procerus and nasalis muscles, and perforated about its center by the nasal foramen, a small passageway for the transmission of a small vein from the overlying soft tissues.

The inner surface is concave from side to side, and is traversed from above downward, by a groove for the passage of a branch of the nasociliary nerve.

Articulations

[edit]The nasal articulates with four bones: two of the cranium, the frontal and ethmoid, and two of the face, the opposite nasal and the maxilla.

Other animals

[edit]In primitive bony fish and tetrapods, the nasal bones are the most anterior of a set of four paired bones forming the roof of the skull, being followed in sequence by the frontals, the parietals, and the postparietals. Their form in living species is highly variable, depending on the shape of the head, but they generally form the roof of the snout or beak, running from the nostrils to a position short of the orbits. In most animals, they are generally therefore proportionally larger than in humans or great apes, because of the shortened faces of the latter. Turtles, unusually, lack nasal bones, with the prefrontal bones of the orbit reaching all the way to the nostrils.[2]

Additional images

[edit]-

Lateral wall of nasal cavity, showing ethmoid bone in position.

-

Right nasal bone. Outer surface.

-

Right nasal bone. Inner surface.

See also

[edit]References

[edit] This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 156 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 156 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Lazovic, Goran D.; Daniel, Rollin K.; Janosevic, Ljiljana B.; Kosanovic, Rade M.; Colic, Miodrag M.; Kosins, Aaron M. (1 March 2015). "Rhinoplasty: The Nasal Bones – Anatomy and Analysis". Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 35 (3): 255–263. doi:10.1093/asj/sju050. ISSN 1527-330X. PMID 25805278.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 217–241. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

External links

[edit]- Anatomy figure: 22:02-07 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center—"Anterior view of skull."

- Anatomy photo:29:st-0206 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center—"Orbits and Eye: Bones"

- Anatomy figure: 33:01-03 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center—"The bones of the lateral nasal wall."

- "Anatomy diagram: 34256.000-1". Roche Lexicon – illustrated navigator. Elsevier. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014.