Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Garmisch-Partenkirchen

View on Wikipedia

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2021) |

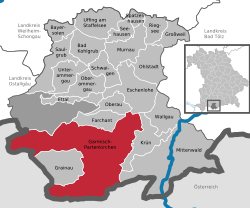

Garmisch-Partenkirchen (German pronunciation: [ˈɡaʁmɪʃ paʁtn̩ˈkɪʁçn̩] ⓘ; Bavarian: Garmasch-Partakurch) is an Alpine ski town in Bavaria, southern Germany. It is the seat of government of the district of Garmisch-Partenkirchen (abbreviated GAP), in the Oberbayern region, which borders Austria. Nearby is Germany's highest mountain, Zugspitze, at 2,962 metres (9,718 ft) above sea level.

Key Information

The town is known as the site of the 1936 Winter Olympic Games, the first to include alpine skiing, and hosts a variety of winter sports competitions.

History

[edit]Garmisch (in the west) and Partenkirchen (in the east) were separate towns for many centuries, and still maintain quite separate identities.

Partenkirchen originated as the Roman town of Partanum on the trade route from Venice to Augsburg and is first mentioned in the year A.D. 15. Its main street, Ludwigsstrasse, follows the original Roman road.

Garmisch was first mentioned some 800 years later as Germaneskau ("German District"), suggesting that at some point a Teutonic tribe took up settlement in the western end of the valley.

During the late 13th century, the valley, as part of the County of Werdenfels, came under the rule of the prince-bishops of Freising and was to remain so until the mediatization of 1803. The area was governed by a prince-bishop's representative known as a Pfleger (caretaker or warden) from Werdenfels Castle situated on a crag north of Garmisch.

The Europeans' arrival to America at the turn of the 16th century led to a boom in shipping and a sharp decline in overland trade, which plunged the region into a centuries-long economic depression. The valley floor was swampy and difficult to farm. Bears, wolves and lynxes were a constant threat to livestock. The population suffered from periodic epidemics, including several serious outbreaks of bubonic plague. Adverse fortunes from disease and crop failure occasionally led to a witch hunt. Most notable of these were the trials and executions of 1589–1596, in which 63 people — more than 10 per cent of the population at the time — were burned at the stake or garroted.

Werdenfels Castle, where the accused were held, tried and executed, became an object of superstitious terror and was abandoned in the 17th century. It was largely torn down in the 1750s and its stones were used to build the baroque Neue Kirche (New Church) on Marienplatz, which was completed in 1752. It replaced the nearby Gothic Alte Kirche (Old Church), parts of which predated Christianity and might have originally been a pagan temple. Used as a storehouse, armory and haybarn for many years, it has since been re-consecrated. Some of its medieval frescoes are still visible.

Garmisch and Partenkirchen remained separate until their respective mayors were forced by Adolf Hitler to combine the two market towns on 1 January 1935[3] in anticipation of the 1936 Winter Olympic Games. Today, the united town is casually (but incorrectly) referred to as Garmisch, much to the dismay of Partenkirchen's residents. Most visitors will notice the slightly more modern feel of Garmisch while the fresco-filled, cobblestoned streets of Partenkirchen have a generally more historic appearance. Early mornings and late afternoons in pleasant weather often find local traffic stopped while the dairy cows are herded to and from the nearby mountain meadows.[citation needed]

During World War II, Garmisch-Partenkirchen was a major hospital centre for the German military. On 29 April 1945, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, which had remained undestroyed, was handed over to the US Army without a fight.

Climate

[edit]Garmisch-Partenkirchen leans towards an oceanic climate,[4] and its winters are colder than the rest of Bavaria. Due to its higher elevation, it is very close to the winters associated with continental climates; it has a relatively wet and snowy climate, with high precipitation year-round. As of 2013 the regions in the west and east of the town were cited as having highest numbers of thunderstorm days in Europe.[5]

| Climate data for Garmisch-Partenkirchen (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1936–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.0 (66.2) |

21.4 (70.5) |

25.3 (77.5) |

29.2 (84.6) |

31.7 (89.1) |

35.1 (95.2) |

36.4 (97.5) |

35.7 (96.3) |

32.0 (89.6) |

27.8 (82.0) |

23.7 (74.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

36.4 (97.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

5.7 (42.3) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.5 (58.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

8.2 (46.8) |

3.3 (37.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.1 (28.2) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

7.8 (46.0) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.5 (59.9) |

17.1 (62.8) |

16.6 (61.9) |

12.5 (54.5) |

8.2 (46.8) |

2.7 (36.9) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −5.8 (21.6) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

1.7 (35.1) |

5.9 (42.6) |

9.6 (49.3) |

11.2 (52.2) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.5 (45.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

2.8 (37.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.8 (−14.4) |

−29.3 (−20.7) |

−21.2 (−6.2) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

3.5 (38.3) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−2.3 (27.9) |

−8.2 (17.2) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

−24.4 (−11.9) |

−29.3 (−20.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 77.3 (3.04) |

65.5 (2.58) |

90.3 (3.56) |

87.2 (3.43) |

143.4 (5.65) |

179.7 (7.07) |

172.6 (6.80) |

191.9 (7.56) |

115.4 (4.54) |

91.0 (3.58) |

80.8 (3.18) |

77.8 (3.06) |

1,379.3 (54.30) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 14.6 | 13.6 | 15.9 | 15.5 | 18.6 | 19.8 | 19.0 | 18.0 | 16.2 | 13.9 | 14.0 | 15.4 | 195.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 27.4 | 23.6 | 14.9 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 8.9 | 21.1 | 99.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 86.2 | 80.9 | 76.2 | 72.2 | 74.1 | 75.8 | 76.4 | 79.3 | 82.6 | 83.5 | 87.0 | 89.3 | 80.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 74.6 | 106.1 | 148.6 | 168.8 | 172.1 | 176.2 | 201.1 | 199.5 | 163.7 | 135.3 | 80.2 | 55.7 | 1,665.9 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization[6] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: DWD (extremes)[7] | |||||||||||||

Transport

[edit]

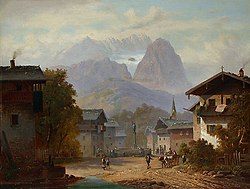

painting by Anton Doll

The town is served by the B 2 as a continuation of the A 95 motorway, which ends at Eschenlohe 16 km north of the town.

Garmisch-Partenkirchen station is on the Munich–Garmisch-Partenkirchen line and the Mittenwald Railway (Garmisch–Mittenwald–Innsbruck). Regional services run every hour to Munich Central Station (München Hauptbahnhof) and Mittenwald and every two hours to Innsbruck Central Station (Innsbruck Hauptbahnhof) and Reutte. In addition there are special seasonal long-distance services, including ICEs, to Berlin, Hamburg, Dortmund, Bremen and Innsbruck.

It is the terminus of the Außerfern Railway to Reutte in Tirol / Kempten im Allgäu and the Bavarian Zugspitze Railway (with sections of rack railway) to the Zugspitze, the highest mountain in Germany.

There are several accessible high and low-level hiking trails from the town that have especially good views.

The nearest airports to the town is Innsbruck Airport which is an hour drive and Munich Airport which is also an hour and half drive from Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

Sports

[edit]

Garmisch-Partenkirchen

Garmisch-Partenkirchen is a favoured holiday spot for skiing, snowboarding, and hiking, having some of the best skiing areas (Garmisch Classic and Zugspitze) in Germany.

It was the site of the 1936 Winter Olympics, the first to feature alpine skiing. It later replaced Sapporo, Japan as the host of the 1940 Winter Olympics, but were cancelled due to World War II. Including the two cancelled cities in 1940, it is the only host city chosen during the World Wars that did not host a subsequent Olympics.

A variety of Nordic and alpine World Cup ski races are held here, usually on the Kandahar Track outside town. Traditionally, a ski jumping contest is held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen on New Year's Day, as a part of the Four Hills Tournament (Vierschanzen-Tournee). The World Alpine Ski Championships were held in Garmisch in 1978 and 2011.

Garmisch-Partenkirchen was a partner in the city of Munich's bid for the 2018 Winter Olympics but the IOC vote held on 6 July 2011 awarded the Games to Pyeongchang. The Winter Olympics were last held in the German-speaking Alps in 1976 in nearby Innsbruck, Austria.

In team sports, the professional former 10-time German champion ice hockey team SC Riessersee play at the Garmisch Olympia Stadium.

The local association football team is 1.FC Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

Event highlights

[edit]

- January – New Year's Ski Jump

- 6 January – "Hornschlittenrennen"

- January / February – FIS Alpine Ski World Cup

- February – Historic bob-race on the olympic track at Riessersee

- 30.04. – "Georgimarkt" Partenkirchen

- May–October – "Musik im Park"

- June – Zugspitz Ultratrail trail running around the Zugspitze.

- Richard-Strauss-Festival

- July The first weekend– BMW Motorbike Days

- 15.07. - White night

- July / August "Festwoche" Festival in Garmisch and Partenkirchen

- August – "Alpentestival"

- August/September – Straßen.Kunst.Festival (Streetart-Festival)

- November– "Martinimarkt" Garmisch

Public institutions

[edit]The George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies[8] is also located in Garmisch-Partenkirchen. The Marshall Center is an internationally funded and mostly U.S.-staffed learning and conference centre for governments from around the world, but primarily from the former Soviet Union and Eastern European countries. It was established in June 1993, replacing the U.S. Army Russian Institute. Near the Marshall Center is the American Armed Forces Recreation Centers (Edelweiss Lodge and Resort) in Garmisch that serves U.S. and NATO military and their families. A number of U.S. troops and civilians are stationed in the town to provide logistical support to the Marshall Center and Edelweiss Recreation Center. The German Centre for Pediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology, the largest specialized centre for the treatment of children and adolescents with rheumatic diseases in Europe, has been active in Garmisch-Partenkirchen since 1952.

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Garmisch-Partenkirchen is twinned with:[9]

Aspen, United States

Aspen, United States Chamonix-Mont-Blanc, France

Chamonix-Mont-Blanc, France Lahti, Finland

Lahti, Finland

Notable people

[edit]

- Hermann Levi (1839–1900), Jewish orchestral conductor[10]

- Richard Strauss (1864–1949), leading German composer[11] of the late Romantic and early modern eras.[12]

- Ludwig Thoma (1867–1921), author, publisher and editor, who gained popularity through his partially exaggerated description of everyday Bavarian life

- Alfred Gerstenberg (1893–1959), Luftwaffe general

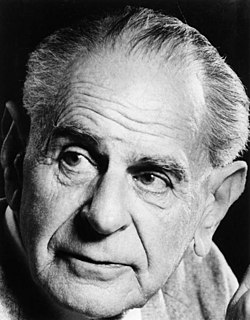

- Sir Karl Popper CH FBA FRS (1902–1994), Austrian-British philosopher[13] and professor, regarded as one of the greatest philosophers of science of the 20th century

- Franz Klarwein (1914–1991), operatic tenor, husband of Sári Barabás[14]

- Christoph Hermann Probst (1918–1943), student of medicine and member of the White Rose (Weiße Rose) resistance group

- Michael Ende (1929–1995), writer of fantasy and children's fiction, best known for The Neverending Story

- Hank Smith (1934–2002), Canadian country music singer

- Wolfgang Seiler (born 1940), biogeochemist and climatologist; after he retired, he was environmental officer (voluntary) for the town

- Ulla Mitzdorf (1944–2013), scientist, substantially contributed to diverse areas including physics, chemistry, psychology, physiology, medicine and gender studies

- Robert Rosner (born 1947), astrophysicist and founding director of the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago

- Hans Peter Blochwitz (born 1949), lyric tenor, sings parts in Mozart operas

- Michaela Steiger (born 1964), actress for theatre, film, television

- Marina Anna Eich (born 1976), film actress and producer[15]

Notable people in sports

[edit]

- Thaddäus Robl (1877–1910), cyclist

- Hanns Kilian (1905–1981), bobsledder

- Matthias Wörndle (1909–1942), cross-country skier

- Roman Wörndle (1913–1942), alpine skier

- Käthe Grasegger (1917–2001), alpine skier

- Michael Pössinger (1919–2003), bobsledder

- Pepi Bader (1941–2021), bobsledder

- Stefan Gaisreiter (born 1947), bobsledder

- Reinhard E. Ketterer (born 1948), figure skater

- Christian Neureuther (born 1949), alpine ski racer

- Rosi Mittermaier (1950–2023), alpine ski racer, double Olympic gold medalist

- Hans-Joachim Stuck (born 1951), racing driver

- Armin Bittner (born 1964), alpine skier

- Andrea Schöpp (born 1965), curler

- Monika Wagner (born 1965), curler

- Martina Beck (née Glagow) (born 1979), biathlete

- Maria Höfl-Riesch (born 1984), alpine skier

- Felix Neureuther (born 1984), alpine skier

- Susanne Riesch (born 1987), alpine skier

- Magdalena Neuner (born 1987), six-time biathlon world champion, Olympic champion, Biathlon World Cup winner

- Miriam Gössner (born 1990), biathlete

- Laura Dahlmeier (1993–2025), biathlete, double Olympic gold medalist

Points of interest

[edit]South of Partenkirchen is the Partnach Gorge,[16] where the Partnach river surges spectacularly through a narrow, 2-kilometre-long (1 mi) gap between high limestone cliffs. The Zugspitze (local name "Zugspitz") is south of Garmisch near the village of Grainau. The highest mountain in Germany, it actually straddles the border with Austria. Also overlooking Garmisch-Partenkirchen is Germany's fourth-highest mountain, the Leutasch Dreitorspitze ("Three-Gate Peak", a name derived from its triple summit).

The King's House on Schachen, a small castle built for Ludwig II of Bavaria, is also located in the mountains south of Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Its grounds contain the Alpengarten auf dem Schachen, an alpine botanical garden.

References

[edit]- ^ Liste der ersten Bürgermeister/Oberbürgermeister in kreisangehörigen Gemeinden, Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik, 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Alle politisch selbständigen Gemeinden mit ausgewählten Merkmalen am 31.12.2023" (in German). Federal Statistical Office of Germany. 28 October 2024. Retrieved 16 November 2024.

- ^ Alois Schwarzmüller 2006 (2006). "Garmisch-Partenkirchen 1. Januar 1935" (in German). Garmisch-Partenkirchen Geschichte. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany Climate Summary". Weatherbase. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ^ "Thunderstorm activity in central and western Europe". ESKP. 28 July 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 12 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Extremwertanalyse der DWD-Stationen, Tagesmaxima, Dekadenrekorde, usw" (in German). DWD. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ "Marshall European Center for Security Studies". Archived from the original on 17 January 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ "Partnerstädte von Garmisch Partenkirchen". buergerservice.gapa.de (in German). Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- ^ Legge, Robin Humphrey (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). pp. 1003–1004.

- ^ Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Karl Popper and Critical Rationalism retrieved December 2017

- ^ German Wiki, Franz Klarwein

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved December 2017

- ^ "Partnach Gorge". Official Website of Garmisch-Partenkirchen. Garmisch-Partenkirchen.de. 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

Garmisch-Partenkirchen

View on GrokipediaGarmisch-Partenkirchen is a municipality and ski resort in the Bavarian Alps of southern Germany, formed on January 1, 1935, by the merger of the adjacent towns of Garmisch and Partenkirchen in preparation for hosting the 1936 Winter Olympics.[1][2] Located at approximately 47°29′N 11°05′E and an elevation of 705 meters above sea level, it serves as the administrative seat of the Garmisch-Partenkirchen district and lies at the foot of the Zugspitze, Germany's highest mountain at 2,962 meters.[3][4] As of the 2022 census, the municipality has a population of 25,480 residents.[5] The town is renowned for its alpine skiing and winter sports infrastructure, including access to the Zugspitze glacier ski area, which offers year-round skiing due to its high elevation and reliable snow cover.[6] It hosted the IV Olympic Winter Games from February 6 to 16, 1936, featuring events in alpine skiing, bobsleigh, and other disciplines amid the scenic backdrop of the Wetterstein Mountains.[7] Beyond winter tourism, Garmisch-Partenkirchen attracts visitors for hiking, cultural festivals, and its preserved Bavarian architecture, contributing significantly to the regional economy through sports and hospitality.[8]

Geography

Location and topography

Garmisch-Partenkirchen lies in the Upper Bavarian district of Garmisch-Partenkirchen, southern Germany, at an elevation of approximately 708 meters above sea level.[9] The municipality occupies a position in the broad Loisach River valley within the Werdenfels region of the Bavarian Alps, roughly 90 kilometers south of Munich.[10] It serves as a strategic gateway to the high Alps due to its placement near the Germany-Austria border, with the Zugspitze massif—straddling the frontier—rising immediately to the south.[11] The town encompasses the adjoining areas of Garmisch and Partenkirchen, situated at the northern base of the Zugspitze, Germany's highest peak at 2,962 meters.[11] Surrounding topography features steep alpine walls and U-shaped valleys sculpted by past glaciations, with elevations rising sharply from the town's 700-meter base to over 2,000 meters in adjacent peaks like the Alpspitze.[12] The Partnach River, an 18-kilometer tributary originating on the Zugspitze massif at 1,440 meters, flows through the area, carving deep gorges such as the Partnachklamm with walls up to 80 meters high.[13] The Loisach River defines the primary valley floor, channeling northward drainage amid limestone-dominated terrain formed during the Tertiary alpine orogeny.[10] Geologically, the region's landscape reflects intense tectonic folding of Mesozoic limestones into recumbent nappes, followed by Pleistocene glacial erosion that hollowed valleys and deposited moraines.[12] Remnant glaciers, including Germany's largest on the Zugspitze's flanks, underscore the area's high-altitude alpine character, with cirques and hanging valleys evident in the Wetterstein Mountains.[11] This topography positions Garmisch-Partenkirchen as a transitional zone between pre-alpine foothills and the central Eastern Alps crystalline core.[12]Climate and environment

Garmisch-Partenkirchen experiences a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb) characterized by cold, snowy winters and mild summers, influenced by its alpine location at approximately 700 meters elevation. Long-term meteorological records indicate average January lows of around -6°C and highs near 3°C, with snowfall accumulation supporting winter sports, while July averages highs of 20-21°C and lows of 10°C. Annual precipitation totals approximately 1,000-1,200 mm, distributed fairly evenly but with peaks in summer thunderstorms and winter snow.[14][15][16] The town holds official status as a premium-class climatic health resort since 1954, attributed to its clean air, low allergen levels, minimal fog, and relatively high sunshine hours—peaking at about 7.7 hours per day in July. Local air quality monitoring consistently reports good to moderate levels, with PM2.5 concentrations rarely exceeding thresholds that pose health risks for the general population. These factors stem from the surrounding forested mountains acting as natural barriers to pollutants, fostering conditions beneficial for respiratory health.[17][18][19] Environmental challenges include periodic avalanche risks during heavy snowfall periods, particularly in steeper surrounding slopes, managed through monitoring and protective infrastructure based on historical hazard data from the Bavarian Alps. The alpine ecosystems support diverse biodiversity, including endemic plant species adapted to high-altitude conditions, though habitat fragmentation from infrastructure development poses ongoing pressures without evidence of acute collapse.[20][21][22]History

Early settlement and medieval period

The region encompassing modern Garmisch-Partenkirchen exhibits early settlement patterns tied to trans-Alpine trade routes, with Partenkirchen originating as the Roman waystation of Partanum circa 15 BC, established along the Via Claudia Augusta linking northern Italy to Augsburg via passes such as the Brenner or Fern.[23] [1] This infrastructure supported commerce in salt, metals, and amber, leveraging the Loisach Valley's strategic position amid the Wetterstein Mountains, where archaeological traces of Roman road engineering persist in the alignment of Ludwigstraße.[24] Pre-Roman occupation by Raeto-Celtic peoples, including hillforts and trade precursors, preceded this Roman overlay following the conquest of Raetia by Drusus in 15 BC, though site-specific artifacts like coins or pottery from Partanum remain sparse compared to broader Bavarian finds.[25] Garmisch developed separately as a Germanic (Teutonic) outpost, first attested around the 8th-9th century AD as Germaneskau ("German District"), reflecting post-Roman migration into alpine clearings for herding and forestry.[26] By the High Middle Ages, the combined area integrated into the Prince-Bishopric of Freising's County of Werdenfels, with feudal administration centered at Werdenfels Castle, erected between 1180 and 1230 atop a spur overlooking the Loisach to enforce tolls and oversee manorial obligations.[27] This ecclesiastical lordship, documented from 1249, imposed tithes and labor on dispersed homesteads, fostering self-sufficient economies reliant on transhumance—seasonal livestock migration to high pastures—causally sustained by the rugged topography that precluded intensive cropping and isolated communities from lowland markets. [28] Ecclesiastical foundations anchored medieval cohesion, with Partenkirchen's Old Church (Alte Kirche) consecrated around 1330 in Romanesque-Gothic style, possibly repurposing earlier pagan sites amid Christianization efforts traceable to 8th-century monastic influences.[29] The first record of Partenkirchen (as Barthinchirchen) dates to 1130, denoting a parish under Freising's bishops, while Garmisch's chapel foundations circa the 15th century preceded baroque reconstructions.[30] These institutions reinforced feudal ties, with tithes funding defenses against incursions, yet the alpine locale preserved pre-feudal customs like communal grazing rights (Almwirtschaft), directly attributable to geographic barriers limiting external integration until Bavarian ducal oversight intensified post-14th century.[31]19th-century development and tourism origins

In the mid-19th century, Garmisch-Partenkirchen began transitioning from a primarily agrarian economy to an emerging destination for leisure seekers, influenced by the Romantic movement's idealization of the Alps as a site for aesthetic and physical rejuvenation. Artists and intellectuals, drawn to the region's dramatic landscapes including the Zugspitze massif, initiated visits that laid the groundwork for tourism; painters such as those capturing the Wetterstein Mountains' vistas promoted the area through works exhibited in urban centers like Munich.[10] This cultural influx was amplified by Bavaria's King Ludwig II, who constructed the King's House on Schachen (Königshaus am Schachen) between 1869 and 1872 as a secluded alpine retreat at 1,866 meters elevation, exemplifying royal patronage of mountainous escapes and attracting nobility seeking similar rustic grandeur.[32] Hiking and spa activities, leveraging local mineral springs in Partenkirchen, gained traction post-1850, shifting local incomes from farming toward accommodating visitors with rudimentary guesthouses.[10] The completion of the Munich–Garmisch-Partenkirchen railway in 1889 marked a pivotal infrastructural advancement, reducing travel time from Bavaria's capital and enabling mass access for middle-class holidaymakers previously deterred by arduous coach journeys.[33] This connectivity spurred hotel construction, including the transformation of existing structures into facilities like the Grand Hotel Sonnenbichl in 1890, which catered to aristocracy and intellectuals with amenities suited for extended stays.[34] Musicians and writers, following the artists' lead, frequented the towns, fostering a nascent cultural tourism economy evidenced by the proliferation of spa facilities and guided excursions.[33] By the late 19th century, visitor numbers had risen sufficiently to diversify employment, with locals supplementing agricultural yields through guiding, lodging, and provisioning, though agriculture remained dominant until the early 20th century.[10] This era's developments embedded Garmisch-Partenkirchen within Bavaria's broader 19th-century tourism boom, where commercial ventures capitalized on natural scenery amid industrialization's urban fatigue, yet relied on verifiable transport links rather than speculative promotion.[35]20th-century merger, Nazi era, and 1936 Winter Olympics

In 1935, the Nazi regime compelled the merger of the neighboring Bavarian municipalities of Garmisch and Partenkirchen into a single administrative unit named Garmisch-Partenkirchen, effective January 1, to create a unified host for the upcoming Winter Olympics. This forced consolidation, directed by Adolf Hitler, overrode local resistance and separate historical identities to streamline preparations and present a monolithic venue capable of accommodating international demands.[1][36] The Nazis leveraged the event for propaganda, aiming to demonstrate regime efficiency, national unity, and Aryan physical superiority while masking discriminatory policies; Hitler ordered the temporary removal of anti-Jewish signs and overt racial propaganda from public spaces to appease foreign scrutiny. New infrastructure included the Olympic Stadium, built with a capacity of 18,326, a 1,525-meter bobsleigh track with ice-lined curves, ski jumps, and expanded accommodations for up to 7,000 additional visitors, straining local resources amid crowds that filled venues and overflowed into surrounding areas. Efforts to sanitize the image faced incomplete success, as Western journalists reported persistent anti-Semitic undercurrents, and boycott campaigns—driven by Jewish organizations and anti-Nazi groups in countries like the United States—highlighted ideological clashes, though they resulted in only marginal non-participation, with 28 nations ultimately attending.[37][38][39] Held from February 6 to 16, 1936, the Games introduced innovations such as the alpine skiing combined event and military patrol (a precursor to modern biathlon), expanding the program's emphasis on mountain disciplines suited to the region's terrain. Germany topped the medal table with 7 golds among 19 total, securing events like ski jumping and bobsleigh, which enhanced the regime's domestic prestige and organizational reputation internationally, even as the Winter edition drew less global controversy than the subsequent Summer Games in Berlin.[36][37]Post-war recovery and modern developments

Following the end of World War II, Garmisch-Partenkirchen fell under American occupation on April 29, 1945, when U.S. forces from the 101st Cavalry Group entered the area without resistance, marking the "Day of the Tigers" in local memory.[40] The town, previously headquarters for German mountain troops, saw its military facilities repurposed by the U.S. Army for rest and recreation centers starting December 3, 1945, providing economic stimulus through troop spending amid broader reconstruction efforts under the Marshall Plan, which allocated funds for Bavarian infrastructure revival by the late 1940s.[41][42] This military presence, enduring until the 1990s in forms like the Edelweiss Lodge, facilitated initial post-war stability by injecting demand into lodging and services, with over 80 years of U.S. ties commemorated in local events as late as 2025.[43] Tourism began reviving in the 1950s, building on the 1936 Winter Olympics legacy of alpine events and infrastructure like the Olympic ski stadium, which drew international skiers and solidified winter sports as an economic pillar. U.S. military R&R programs extended Olympic-era venues for troop vacations, transitioning to civilian use as occupation eased, with visitor numbers climbing through the decade via enhanced rail links and promoted ski facilities, contributing to Bavaria's regional GDP growth averaging 7-8% annually in the post-war boom.[42][44] By the 1960s, the town's Olympic heritage had evolved into sustained sports tourism, hosting events that preserved facilities like the bobsleigh run while adapting to mechanical lifts for broader access.[45] In recent decades, infrastructure investments have modernized access, exemplified by the 2017-2018 replacement of the Eibsee-Zugspitze cable car with a new system featuring the world's tallest support tower at 127 meters and capacity for 580 passengers per hour, reducing wait times and elevating tourism to the 2,962-meter summit.[46][47] However, this growth has intensified overtourism pressures, particularly around adjacent sites like Eibsee lake, where social media-driven crowds in the 2020s have strained paths, parking, and waste management, prompting local calls for visitor caps amid 2025 summer peaks exceeding infrastructure limits.[48] Housing markets reflect financialization trends, with short-term rentals and second homes driving prices beyond local affordability—average square-meter costs surpassing €7,000 by 2023—exacerbating displacement for residents as tourism absorbs properties once used for year-round living. Socially, the area contends with an aging population, where Bavarian statistics show the median age in Garmisch-Partenkirchen district rising to 45.5 by 2020, above the state average, due to net out-migration of youth offset by retiree inflows and limited family-oriented jobs.[49][50] Amid globalization, traditional Bavarian customs—such as annual wood-carving festivals and dialect preservation—remain robust, supported by community initiatives that integrate seasonal workers while resisting dilution, as evidenced by stable participation rates in local heritage events through 2025.Demographics

Population trends and statistics

As of 31 March 2025, Garmisch-Partenkirchen had a population of 28,283 inhabitants, reflecting updated estimates from the 2022 census base.[51] The town's population grew from 25,742 in 1987 to 27,482 in 2011, before declining to 25,581 as recorded in the 2022 census, indicating a recent downward trend amid regional alpine aging patterns.[52] This shift aligns with the district's highest average age in Upper Bavaria, projected at 47.5 years, contributing to low natural increase.[53] In 2022, vital statistics showed 214 live births (7.8 per 1,000 inhabitants) and 257 deaths (9.4 per 1,000), yielding a negative natural balance of 43 persons.[52] Migration recorded 2,112 arrivals (77.5 per 1,000) against 2,204 departures (80.9 per 1,000), resulting in a net loss of 92 persons and underscoring limited inflow relative to outflows.[52] Household composition in 1987 comprised 13,708 private households, with 31.5% (4,321) being single-person units, a figure indicative of early trends toward smaller family sizes that have persisted in aging rural-alpine settings.[52]| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1987 | 25,742 |

| 2011 | 27,482 |

| 2022 | 25,581 |

Ethnic and cultural composition

Garmisch-Partenkirchen's population is predominantly ethnic German, with Bavarian roots tracing to early Alpine settlements, comprising approximately 77% of residents as of 2023, while foreign nationals account for 23.1%, or 6,848 individuals, largely from EU countries such as Romania, Poland, and Turkey, often employed in tourism and services.[54][55] This elevated foreign share relative to Bavaria's average of 9% reflects seasonal labor demands in hospitality rather than permanent settlement patterns, maintaining overall Bavarian homogeneity amid transient influences.[56] Culturally, the town embodies conservative Bavarian norms shaped by Catholic heritage and rural traditions, with Roman Catholicism predominant among natives, aligning with Bavaria's 70% adherence rate historically sustained through church-centric community life.[57] The Austro-Bavarian dialect persists in daily use, preserving linguistic isolation fostered by the town's high-altitude geography and limited external integration until 19th-century tourism.[58] Local customs, including folk festivals and alpine husbandry practices, reinforce social cohesion, with minimal dilution from immigrant groups whose cultural imprint remains peripheral to core Bavarian identity.[59]Economy

Tourism as primary driver

Tourism constitutes the dominant sector of Garmisch-Partenkirchen's economy, attracting visitors primarily for winter sports such as skiing and summer activities including hiking in the surrounding Alps. In 2022, the municipality recorded 1.59 million overnight stays, reflecting a high volume relative to its population of approximately 27,000 residents.[60] This figure rose to 1.22 million in 2024, marking a 7% increase from 2023 and indicating post-pandemic recovery, with around 450,000 guest arrivals annually supporting extensive accommodation and service infrastructure.[61] [62] Key infrastructure like the Bayerische Zugspitzbahn, which operates the cogwheel train from Garmisch-Partenkirchen to the Zugspitze plateau and associated cable cars, generates substantial revenue, with 50.8 million euros from railways and lifts in the fiscal year reported, contributing directly to local fiscal stability through municipal ownership.[63] These operations facilitate access to high-altitude attractions, bolstering year-round tourism despite seasonal peaks in winter, and tourism as a whole accounts for the majority of economic activity, fostering job creation in hospitality, transport, and related services.[64] While tourism drives employment and revenue, it imposes strains including resource pressure and environmental impacts from high visitor densities, particularly at sites like Eibsee lake near the town, where social media-driven influxes have prompted concerns over overcrowding and ecological degradation based on local observations and reports.[48] Seasonality exacerbates these issues, with winter concentrations leading to infrastructure demands that challenge sustainable management, though empirical data from regional studies highlight the need for balanced growth to mitigate long-term effects on local ecosystems and resident quality of life.[65]Other economic sectors and challenges

Agriculture in the Garmisch-Partenkirchen district remains small-scale and fragmented, with approximately 1,000 farms operating primarily on grassland for dairy production and alpine pasturing, constrained by mountainous terrain that limits arable land to minimal areas around valleys like Farchant and Uffing.[66] [67] Over 80% of these farms manage less than 10 hectares, emphasizing part-time operations (Nebenerwerb) that integrate with tourism or crafts rather than standalone viability.[67] Crafts (Handwerk) and trade form secondary pillars, including traditional woodworking, metalworking, and precision trades that leverage local skills, alongside construction tied to infrastructure needs; these sectors have driven post-merger growth but employ far fewer than services, with the district's economy reflecting Bavaria's emphasis on decentralized, family-run enterprises over large-scale industry.[68] Tourism dominance exacerbates seasonal unemployment, as many jobs in ancillary services fluctuate with visitor peaks, leading to higher off-season idleness compared to Germany's national average of around 5-6% in stable periods, though district-specific data underscores structural reliance on transient labor.[69] Real estate speculation, fueled by second-home demand and short-term rentals, has inflated prices, with average apartment costs reaching 6,030 € per square meter by 2023, pricing out locals and straining affordability in a region where tourism converts residential space to commercial use.[70] [71] Bavarian policies promoting market-driven zoning and incentives for local housing aim to mitigate this, yet 2025 analyses highlight persistent shortages, with the district offering limited non-tourist living space relative to its high-end market status in Upper Bavaria.[72]Government and public services

Local administration

Garmisch-Partenkirchen functions as a Marktgemeinde (market town) within the Garmisch-Partenkirchen district of Upper Bavaria, serving as the administrative seat for the district under Bavarian municipal governance.[73] The local government operates under the Gemeindeordnungen (municipal codes) of Bavaria, with executive authority vested in a directly elected mayor (Bürgermeister or Bürgermeisterin) who serves a six-year term and oversees a town council (Gemeinderat) responsible for legislative decisions. The current mayor, Elisabeth Koch of the Christian Social Union (CSU), assumed office on May 1, 2020, following a direct election.[74] Municipal policies prioritize tourism regulation to sustain economic reliance on visitors while preserving alpine ecosystems and infrastructure, including conservation efforts like seasonal closures of natural sites such as the Partnachklamm gorge for safety amid ice hazards (closed January 27 to April 11, 2025).[73] Traffic management forms a key component, with initiatives such as the construction of a dedicated bike path (Radweg) on Enzianstraße beginning August 25, 2025, involving temporary road closures to mitigate congestion from seasonal tourist influxes.[73] These measures reflect a strategic shift toward year-round tourism embedded in the town's political agenda, aiming to diversify beyond winter sports while addressing environmental pressures.[75] Budgeting adheres to principles of fiscal restraint, as demonstrated by the 2025 municipal budget, which achieved balance without incurring new debt by drawing on established reserves—a pattern consistent with prior years' positive closings.[76][77] Public records indicate approvals in record time, underscoring efficient resource allocation amid tourism-driven revenues.[78]Public institutions and infrastructure

Garmisch-Partenkirchen maintains a network of public schools under the Bavarian education system, including primary schools (Grundschulen) and secondary institutions such as the Werdenfels-Gymnasium and the Bürgermeister Schütte Grund- und Mittelschule.[79] [80] Attendance at state and municipal schools is compulsory and free for children aged 6 to 15.[81] The Klinikum Garmisch-Partenkirchen serves as the primary hospital, offering comprehensive medical services including emergency care, internal medicine, gynecology, and specialized traumatology for sports-related injuries prevalent among climbers and skiers.[82] [83] Emergency services operate via national lines—police at 110 and fire/ambulance at 112—with district resources supporting rapid response to incidents amplified by seasonal tourist influxes.[84] Waste management is handled by the Gemeindewerke Garmisch-Partenkirchen, which schedules regular collections for household, organic, and recyclable waste to accommodate both residents and high visitor volumes.[85] The district's Abfallwirtschaft office provides advisory services on disposal, aligning with Bavaria's regional emphasis on recycling and sustainable practices amid tourism pressures.[86] Public safety remains robust, with the district recording 4,373 offenses in 2023 (excluding immigration violations), a 2.8% increase from prior years but with declining violent crime, positioning it among Bavaria's safer areas at approximately 4,174 incidents per 100,000 inhabitants.[87] [88] This efficacy supports the town's appeal as a secure destination, though statistics reflect only police-recorded cases.[89]Transport

Road and rail connectivity

Garmisch-Partenkirchen is accessible by road primarily via the Bundesautobahn A95, which links Munich to the town over approximately 90 kilometers, with the motorway terminating near Eschenlohe before transitioning to Bundesstraße B2 into the center.[90] The A95 provides efficient connectivity from northern Bavaria, though traffic volumes increase during peak tourist seasons, contributing to congestion on the final B2 stretch.[91] Rail services operate on the Munich–Garmisch-Partenkirchen line, with regional trains (RB/RE) departing frequently from Garmisch-Partenkirchen station to Munich Hauptbahnhof, covering 80 kilometers in an average of 1 hour 20 minutes, with the fastest services taking as little as 1 hour 3 minutes.[92][93] These Deutsche Bahn regional trains run hourly without changes, facilitating daily commuting and tourism flows.[94] The railway's establishment in 1889 marked a pivotal development, connecting the isolated alpine communities to Munich and catalyzing economic growth through enhanced accessibility for visitors and trade.[95][10] Local bus networks, including city buses and Regionalverkehr Oberbayern (RVO) lines, provide intra-town and regional links, with routes connecting key sites like the town hall, train station, and Marienplatz; guest cards issued by accommodations often allow free rides on municipal services.[96][97][98] Tourism-driven peaks exacerbate parking shortages, with central areas restricting stays to a maximum of three hours via ticket systems and fee-based lots filling rapidly, prompting recommendations for public transport alternatives to mitigate gridlock.[99]Access to airports and regional links

Garmisch-Partenkirchen lacks a local airport and relies on nearby international facilities for air travel. Munich Airport (MUC), the primary hub for the region, lies approximately 109 kilometers to the northeast, with direct train connections averaging 2 hours and 22 minutes via regional services operated by Deutsche Bahn.[100] Bus options, such as those provided by FlixBus, cover the distance in about 2 hours and 5 minutes, starting from fares around €21.[101] Private shuttle transfers are also available, typically taking 1 hour and 29 minutes for the 126-kilometer route, catering to tourists seeking door-to-door service.[102] Closer regional access is provided by Innsbruck Airport (INN) in Austria, situated 32.4 kilometers southeast across the border, facilitating shorter transfers for flights to Central Europe.[103] Direct buses from Garmisch-Partenkirchen to Innsbruck city center, operated by FlixBus every four hours, take 59 minutes over 56 kilometers, with onward connections to the airport adding minimal time.[104] Train services to Innsbruck Hauptbahnhof average 2 hours and 41 minutes for the 34-kilometer stretch, supporting cross-border regional links that integrate with Tyrolean transport networks.[105] Private transfers to Innsbruck Airport are common, emphasizing the town's connectivity to Austrian alpine routes. These airport links bolster Garmisch-Partenkirchen's role in broader Bavarian-Austrian tourism corridors, with services like group rail passes and frequent departures ensuring reliable access without personal vehicles. Memmingen Airport (FMM), 85 kilometers west, serves as a secondary low-cost option but sees less utilization due to fewer direct flights.[103]Culture and traditions

Bavarian heritage and festivals

Garmisch-Partenkirchen maintains core Bavarian cultural elements, including traditional attire like Lederhosen for men and Dirndl for women, which originated as practical working garments but evolved into symbols of regional identity worn during communal gatherings and celebrations.[106] These costumes, often handmade with embroidered details, reflect historical craftsmanship tied to alpine livelihoods such as farming and herding, and their use fosters a sense of continuity amid modernization.[59] Local brass bands, drawing from longstanding Bavarian musical traditions linked to guild processions and folk ensembles, perform at events across the town, including parades that feature brass instruments like trumpets and tubas in harmonious marches.[107] The annual Bavaria Brassband Festival, held in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, culminates in a grand parade through the streets, showcasing international and local groups in a display of disciplined ensemble playing rooted in 19th-century community bands.[107] Such performances preserve acoustic heritage while reinforcing social bonds through collective participation. Prominent festivals include the Festwochen, a beer festival in August that echoes Oktoberfest formats with tents serving regional brews, accompanied by folk dances, live music, and artisan markets attracting thousands of attendees.[108] The Partenkirchen Festwoche, a week-long event with its 68th iteration documented in recent years, emphasizes traditional costumes, alpine folk tunes, and communal feasting to honor local history.[109] Additional observances feature the Fosnacht carnival in late winter, involving masked parades and satirical customs derived from pre-Lenten rites, and the Maypole erection on May 1 by the Garmisch fire brigade, a ritual symbolizing spring renewal and village cooperation.[106][110] These practices, sustained through municipal and voluntary efforts, prioritize endogenous cultural transmission over external influences, with empirical continuity evident in annual repetitions and participation rates exceeding local population figures during peak events.[111] Preservation initiatives, including costume workshops and band rehearsals, ensure transmission to younger generations, countering dilution from urbanization.[112]Arts, architecture, and local customs

The architecture of Partenkirchen prominently features Baroque churches from the early 18th century, including St. Martin's Parish Church, constructed between 1730 and 1734 as a prime example of South German Baroque style with a simple exterior and opulent interior decorations such as frescoes and ornate altars.[113][114] The Parish Church of St. Peter and Paul, erected from 1734 to 1746, incorporates a hall nave, Veronese red marble high altar, and ceiling frescoes depicting the martyrdom of its patrons, reflecting the era's emphasis on dramatic religious iconography.[115] Partenkirchen's built heritage extends to Lüftlmalerei, a traditional facade fresco technique originating in the Baroque period, where artists painted illusory architectural elements, religious scenes, and folk motifs on house exteriors to evoke depth and narrative, with many examples preserved on cobblestoned streets dating to the 1700s and later restorations.[31] These murals, often featuring saints like St. Apollonia and St. Mauritius, serve as a customary expression of Bavarian piety and craftsmanship, maintained through local preservation efforts.[116] Local customs emphasize artisanal traditions, particularly wood carving and related handicrafts, with family-run workshops in Garmisch-Partenkirchen producing detailed religious figures and decorative items using techniques passed down regionally for centuries, supported by initiatives like the "INSER HOAMAT" brand to promote authentic Bavarian products.[117][118] This craft, integral to community identity, involves meticulous handwork in lime wood, echoing historical monastic influences in the Upper Bavarian Alps.[119]Sports and events

Winter sports prominence

Garmisch-Partenkirchen hosts two primary alpine ski areas central to its winter sports profile: the Garmisch-Classic resort, offering 40 kilometers of groomed pistes with a mix of 17% easy, 60% intermediate, and 23% difficult terrain, and the adjacent Zugspitze glacier ski area, featuring 20 kilometers of slopes accessible via cog railway, gondolas, and chairlifts up to 2,720 meters elevation.[120][6] These facilities provide year-round skiing on the glacier, with varied descents including the region's longest run exceeding 8 kilometers, supported by 26 lifts in the combined zone under the Top Snow Card system.[121] Infrastructure developed from the 1936 Winter Olympics, which debuted alpine skiing events and prompted construction of foundational venues like slopes and access systems, has been modernized with aerial trams, weather-protected chairlifts, and snowmaking to maintain elite standards amid elevation advantages up to 2,050 meters in Garmisch-Classic.[122] This setup enables reliable conditions for downhill, slalom, and super-G disciplines, with piste classifications emphasizing intermediate and advanced runs that challenge competitors through wooded bowls and open faces.[123] The resorts function as preparation sites for international ski teams, leveraging consistent snow cover and technical terrain for pre-competition acclimation, as evidenced by U.S. Ski Team deployments for super-G tuning.[124] Economically, this alpine focus directly bolsters sustained tourism inflows, with winter sports comprising a core revenue driver in the locality—rooted in post-Olympic venue legacies that elevated the town's profile and visitor dependency on ski infrastructure, contributing to broader Alpine regional output where skiing accounts for significant consumer expenditure.[125][126][127]Major events and Olympic legacy

Garmisch-Partenkirchen hosted the 1936 Winter Olympics from February 6 to 16, drawing 646 athletes from 28 nations across 17 events in bobsleigh, ice hockey, skating, and skiing disciplines.[7] Organized under the Nazi regime, the games emphasized efficient infrastructure development, including the Große Olympiaschanze ski jump and the bobsleigh run on the Gudiberg hill, which facilitated technical standardization in winter sports despite the event's propagandistic overlay aimed at projecting German organizational prowess internationally.[45] While critics highlight the politicization, including mandatory salutes and exclusionary policies, the tangible outputs—such as purpose-built venues operational into the postwar era—provided lasting venues for competitive skiing and sliding events.[128] The Olympic infrastructure underpinned subsequent major competitions, notably the 1978 FIS Alpine World Ski Championships, which featured downhill, slalom, giant slalom, and combined events on the Kandahar course, drawing top international fields and reinforcing the site's suitability for high-speed alpine racing.[129] Annual FIS Alpine Ski World Cup races, integrated since the 1960s on the same slopes, have included slalom and super-G disciplines, with the 2022 men's slalom marking a return after an 11-year hiatus and events scheduled through 2025.[130] The New Year's ski jumping leg of the Four Hills Tournament, held since 1954 at the Olympic hill, annually attracts crowds exceeding 25,000, perpetuating pre-Olympic traditions from 1922 while leveraging 1936-era facilities.[131] The Olympic legacy manifests in sustained infrastructure utility and economic uplift, with venues like the Kandahar run enabling over 50 years of World Cup continuity and fostering sports tourism that contributes significantly to local revenue as of 2025.[132] Though initial Nazi investments were tied to regime goals, the apolitical endurance of these assets—refurbished postwar without ideological residue—has standardized event hosting protocols, such as slope homologation for FIS standards, yielding verifiable advancements in athlete safety and competition consistency over decades.[130] This dual aspect—propaganda origins balanced against infrastructural pragmatism—positions Garmisch-Partenkirchen as a benchmark for alpine event longevity, with facilities supporting elite training and races absent comparable politicization in modern iterations.[124]International relations

Twin towns and partnerships

Garmisch-Partenkirchen maintains formal partnerships with three international towns, each a prominent winter sports destination: Aspen in Colorado, United States; Chamonix in France; and Lahti in Finland.[133] These ties, established as part of post-World War II efforts to promote international understanding, emphasize cultural exchange, reciprocal tourism, and youth mobility programs.[134] The partnership with Aspen dates to September 23, 1966, initiated by local resident Gretl Uhl to facilitate exchanges between alpine communities.[135] It has enabled numerous visits, work opportunities, and residencies for youth and adults, strengthening economic ties through shared winter tourism interests.[134] The 50th anniversary in 2016 featured large delegations and reaffirmed commitments to mutual benefits.[136] The link with Chamonix began in 1973, marked by annual cultural events such as music band visits and joint celebrations.[137] The 40th anniversary in 2013 included collaborative festivities, while the 50th in 2023 highlighted ongoing exchanges like group travels and tourism initiatives.[138] These activities promote cross-border youth programs and economic reciprocity in alpine recreation.[139] The most recent partnership, with Lahti, was ratified in 1987 by local officials including Seppo Välisalo.[140] Focused on Nordic sports heritage, it supports similar goals of cultural and youth exchanges, contributing to sustained visitor flows and promotional collaborations.[133]| Partner City | Country | Established | Key Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspen | United States | 1966 | Youth mobility, tourism synergy [134] |

| Chamonix | France | 1973 | Cultural events, reciprocal visits [137] |

| Lahti | Finland | 1987 | Sports heritage exchanges [140] |