Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Gehenna

View on WikipediaGehenna (/ɡɪˈhɛnə/ ghi-HEN-ə; Ancient Greek: Γέεννα, romanized: Géenna) or Gehinnom (Hebrew: גֵּיא בֶן־הִנֹּם, romanized: Gēʾ ḇen-Hīnnōm or גֵי־הִנֹּם, Gē-Hīnnōm, 'Valley of Hinnom') is a Biblical toponym that has acquired various theological connotations, including as a place of divine punishment, in Jewish eschatology.

Key Information

The place is first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as part of the border between the tribes of Judah and Benjamin (Joshua 15:8). During the late First Temple period, it was the site of the Tophet, where some of the kings of Judah had sacrificed their children by fire (Jeremiah 7:31).[1] Thereafter, it was cursed by the biblical prophet Jeremiah (Jeremiah 19:2–6).[2]

In later rabbinic literature, "Gehinnom" became associated with divine punishment as the destination of the wicked for the atonement of their sins.[3][4] The term is different from the more neutral term Sheol, the abode of the dead. The King James Version of the Bible translates both with the Anglo-Saxon word hell.

Etymology

[edit]The Hebrew Bible refers to the valley as the "Valley of the son of Hinnom" (Hebrew: גֵּיא בֶן־הִנֹּם),[5][6] or "Valley of Hinnom" (גֵי־הִנֹּם).[7] In Mishnaic Hebrew and Judeo-Aramaic languages, the name was contracted into Gēhīnnōm (גֵיהִינֹּם) or Gēhīnnām (גֵיהִינָּם) meaning "hell".

The English name "Gehenna" derives from the Koine Greek transliteration (Γέεννα) found in the New Testament.[8]

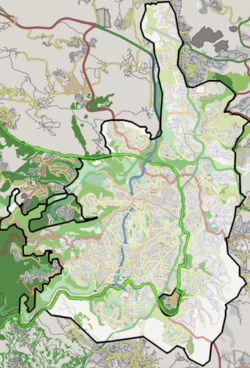

Geography

[edit]

The exact location of the Valley of Hinnom is disputed. George Adam Smith wrote in 1907 that there are three possible locations considered by historical writers:[9]

- East of the Old City (today identified as the Valley of Josaphat)

- Within the Old City (today identified as the Tyropoeon Valley): Many commentaries give the location as below the southern wall of ancient Jerusalem, stretching from the foot of Mount Zion eastward past the Tyropoeon Valley to the Kidron Valley. However, the Tyropoeon Valley is usually no longer associated with the Valley of Hinnom because during the period of Ahaz and Manasseh, the Tyropoeon lay within the city walls and child sacrifice would have been practiced outside the walls of the city.

- Wadi ar-Rababi: Dalman (1930),[10] Bailey (1986)[11] and Watson (1992)[12] identify the Wadi al-Rababi, which fits the description of Joshua that the Hinnom Valley ran east to west and lay outside the city walls. According to Joshua, the valley began at Ein Rogel. If the modern Bir Ayyub in Silwan is Ein Rogel, then Wadi ar-Rababi, which begins there, is Hinnom.[13]

Archaeology

[edit]Child sacrifice at other Tophets contemporary with the Bible accounts (700–600 BCE) of the reigns of Ahaz and Manasseh has been established, such as the bones of children sacrificed at the Tophet to the goddess Tanit in Phoenician Carthage,[14] and also child sacrifice in ancient Syria-Palestine.[15] Scholars such as Mosca (1975) have concluded that the sacrifice recorded in the Hebrew Bible, such as Jeremiah's comment that the worshippers of Baal had "filled this place with the blood of innocents", is literal.[16][17] Yet, the biblical words in the Book of Jeremiah describe events taking place in the seventh century in the place of Ben-Hinnom: "Because they [the Israelites] have forsaken Me and have made this an alien place and have burned sacrifices in it to other gods, that neither they nor their forefathers nor the kings of Judah had ever known, and because they have filled this place with the blood of the innocent and have built the high places of Baal to burn their sons in the fire as burnt offerings to Baal, a thing which I never commanded or spoke of, nor did it ever enter My mind; therefore, behold, days are coming", declares the Lord, "when this place will no longer be called Topheth or the valley of Ben-Hinnom, but rather the valley of Slaughter".[18] J. Day, Heider, and Mosca believe that the Moloch cult took place in the valley of Hinnom at the Topheth.[19]

No archaeological evidence such as mass children's graves has been found; however, it has been suggested that such a find may be compromised by the heavy population history of the Jerusalem area compared to the Tophet found in Tunisia.[20] The site would also have been disrupted by the actions of Josiah "And he defiled Topheth, which is in the valley of the children of Hinnom, that no man might make his son or his daughter to pass through the fire to Molech." (2 Kings 23). A minority of scholars have attempted to argue that the Bible does not portray actual child sacrifice, but only dedication to the god by fire; however, they are judged to have been "convincingly disproved" (Hay, 2011).[21]

There is evidence however that the southwest shoulder of this valley (Ketef Hinnom) was a burial location with numerous burial chambers that were reused by generations of families from as early as the seventh until the fifth century BCE. The use of this area for tombs continued into the first centuries BCE and CE. By 70 CE, the area was not only a burial site but also a place for cremation of the dead with the arrival of the Tenth Roman Legion, who were the only group known to practice cremation in this region.[22]

The concept of Gehinnom

[edit]Judaism

[edit]Hebrew Bible

[edit]The oldest historical reference to “the Valley of the Son of Hinnom” is found in the Book of Joshua (15:8 and 18:16) which describe tribal boundaries.[1] The following reference to the valley is at the time of King Ahaz of Judah, who, according to 2 Chronicles 28:3, “burnt incense in the valley of the son of Hinnom, and burnt his children in the fire”.[1] Later, in 33:6, it is said that Ahaz's grandson, king Manasseh of Judah, also “caused his children to pass through the fire in the valley of the son of Hinnom”. Debate remains as to whether the phrase "cause his children to pass through the fire" referred to a religious ceremony in which the Moloch priest would walk the child between two lanes of fire, or to literal child sacrifice wherein the child is thrown into the fire.

The Book of Isaiah does not mention Gehenna by name, but the "burning place" (30:33) in which the Assyrian army is to be destroyed, may be read in Hebrew as "Topheth". Similarly, Isaiah 66:24 describes the bodies of sinners burning near Jerusalem.

During the reign of Josiah, Jeremiah condemned the Topheth worship which was conducted in the Hinnom valley (7:31–32, 32:35). Josiah destroyed the shrine of Moloch on Topheth to prevent anyone sacrificing children there (2 Kings 23:10). Despite Josiah's ending of the practice, Jeremiah prophesied that Jerusalem itself would be made like Gehenna and Topheth (19:2–6, 19:11–14).

A purely geographical reference appears in Nehemiah 11:30: the exiles returning from Babylon encamped from Beersheba to Hinnom.

Targums (Aramaic translations)

[edit]

The Targums (ancient Jewish paraphrase-translations of the Hebrew Bible) frequently supply the term "Gehinnom" to verses touching upon resurrection, judgment, and the fate of the wicked.[23] For example, Targum Jonathan to Isaiah 66:24 interprets the Biblical phrase "they [the corpses of sinners] shall be an abhorrence to all flesh" as "the evildoers shall be judged in Gehenna until the righteous say of them: We have seen enough".[24]

Rabbinical Judaism

[edit]Gehinnom[25] became a figurative name for the place of spiritual purification for the wicked dead in Judaism.[26] According to most Jewish sources, the period of purification or punishment is limited to only 12 months and every Sabbath day is excluded from punishment, while the fires of Gehinnom are banked and its tortures are suspended. For the duration of Shabbat, the spirits who are serving time there are released to roam the earth. At Motza'ei Shabbat, the angel Dumah, who has charge over the souls of the wicked, herds them back for another week of torment.[4] After this the soul will move on to Olam Ha-Ba (the world to come), be destroyed, or continue to exist in a state of consciousness of remorse.[27]

In classic rabbinic sources, Gehinnom occasionally occurs as a place of punishment or destruction of the wicked.[28] Rabbi Joshua ben Levi is said to have wandered through Gehenna, like Dante, under the guidance of the angel Duma. Joshua describes seven chambers of Gehenna, each one presided over by a famous sinner from Jewish history, and populated by deceased sinners suffering brutal punishments.[29] According to another rabbinic story, the ancient Israelite leader Jair once threatened to burn alive those individuals who refused to worship Baal. In response, God sent the angel Nathaniel, who rescued the individuals and declared to Jair that "you will die, and die by fire, a fire in which you will abide forever."[30]

Rabbinic texts contain various answers to the questions of who suffers in Gehenna and for how long. According to the Tosefta, normal sinners are punished in Gehenna for 12 months, after which their souls leave Gehenna and turn into dust; while heretics, those who abandon the community (porshim midarkhei tzibur), and those who cause the masses to sin, suffer in Gehenna eternally.[31] The Talmud states that all who enter Gehenna eventually leave it, except for adulterers, those who humiliate others in public, and those who call others by derogatory names.[32]

The traditional explanation that a burning rubbish heap in the Valley of Hinnom south of Jerusalem gave rise to the idea of a fiery Gehenna of judgment is attributed to Rabbi David Kimhi (c. 1200 CE). He maintained that historically, in this valley fires were kept burning perpetually to consume the filth and cadavers thrown into it; therefore, the judgment of the evil after death was metaphorically named after the valley.[33] While this claim is logically plausible,[34] there is no direct archaeological nor literary evidence for it.[35]

Maimonides declares, in his 13 principles of faith, that the descriptions of Gehinnom as a place of punishment in rabbinic literature, were pedagogically motivated inventions to encourage respect of the Torah commandments by mankind, which had been regarded as immature.[36] Instead of being sent to Gehenna, the souls of the wicked would actually get annihilated.[37]

Christianity

[edit]Ethiopian Orthodox Old Testament

[edit]Frequent references to "Gehenna" are also made in the books of Meqabyan, which are considered canonical in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[38]

New Testament

[edit]In the King James Version of the Bible, the term appears 13 times in 11 different verses as Valley of Hinnom, Valley of the son of Hinnom or Valley of the children of Hinnom.

In the synoptic Gospels the various authors describe Jesus, who was Jewish, as using the word Gehenna to describe the opposite to life in the Kingdom (Mark 9:43–48). The term is used 11 times in these writings.[39] In certain usage, the Christian Bible refers to it as a place where both soul (Greek: ψυχή, psyche) and body could be destroyed (Matthew 10:28) in "unquenchable fire" (Mark 9:43).[40]

Christian usage of Gehenna often serves to admonish adherents of the religion to live righteous lives. Examples of Gehenna in the Christian New Testament include:

- Matthew 5:22: "....whoever shall say, 'You fool', shall be guilty enough to go into Gehenna."

- Matthew 5:29: "....it is better for you that one of the parts of your body perish, than for your whole body to be thrown into Gehenna."

- Matthew 5:30: "....better for you that one of the parts of your body perish, than for your whole body to go into Gehenna."

- Matthew 10:28: "....rather fear Him who is able to destroy both soul [Greek: ψυχή] and body in Gehenna."

- Matthew 18:9: "It is better for you to enter life with one eye, than with two eyes to be thrown into the Gehenna...."

- Matthew 23:15: "Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites, because you... make one proselyte...twice as much a child of Gehenna as yourselves."

- Matthew 23:33, to the Pharisees: "You serpents, you brood of vipers, how shall you escape the sentence of Gehenna?"

- Mark 9:43: "It is better for you to enter life crippled, than having your two hands, to go into Gehenna into the unquenchable fire."

- Mark 9:45: "It is better for you to enter life lame, than having your two feet, to be cast into Gehenna."

- Mark 9:47: "It is better for you to enter the Kingdom of God with one eye, than having two eyes, to be cast into Gehenna."

- Luke 12:5: "....fear the One who, after He has killed has authority to cast into Gehenna; yes, I tell you, fear Him."

Another book to use the word Gehenna in the New Testament is James:[41]

- James 3:6: "And the tongue is a fire,...and sets on fire the course of our life, and is set on fire by Gehenna."

New Testament translations

[edit]The New Testament also refers to Hades as a place distinct from Gehenna.[citation needed] Unlike Gehenna, Hades typically conveys neither fire nor punishment but forgetfulness. The Book of Revelation describes Hades being cast into the lake of fire (Revelation 20:14). The King James Version is the only English translation in modern use to translate Sheol, Hades, Tartarus (Greek ταρταρώσας; lemma: ταρταρόω tartaroō), and Gehenna as Hell. In the New Testament, the New International Version, New Living Translation, New American Standard Bible (among others) all reserve the term "hell" for the translation of Gehenna or Tartarus (see above), transliterating Hades as a term directly from the equivalent Greek term.[42]

Treatment of Gehenna in Christianity is significantly affected by whether the distinction in Hebrew and Greek between Gehenna and Hades was maintained:

Translations with a distinction:

- The fourth century Gothic Bible was the first bible translation to use the Germanic root Halja, and maintains a distinction between Hades and Gehenna. However, unlike later translations, Halja (Matt 11:23) is reserved for Hades,[43] and Gehenna is transliterated to Gaiainnan (Matt 5:30), which ironically is the opposite to modern translations that translate Gehenna into Hell and leave Hades untranslated (see below).

- The late fourth century Latin Vulgate transliterates the Greek Γέεννα "gehenna" with "gehenna" (e.g. Matt 5:22) while using "infernus" ("coming from below, of the underworld") to translate ᾅδης (Hades]).

- The 19th century Young's Literal Translation tries to be as literal a translation as possible and does not use the word Hell at all, keeping the words Hades and Gehenna untranslated.[44]

- The 19th century Arabic Van Dyck distinguishes Gehenna from Sheol.

- The 20th century New International Version, New Living Translation and New American Standard Bible reserve the term "Hell" only for when Gehenna or Tartarus is used. All translate Sheol and Hades in a different fashion. For a time the exception to this was the 1984 edition of the New International Version's translation in Luke 16:23, which was its singular rendering of Hades as Hell. The 2011 edition renders it as Hades.

- In texts in Greek, and consistently in the Eastern Orthodox Church, the distinctions present in the originals were often maintained. The Russian Synodal Bible (and one translation by the Old Church Slavonic) also maintain the distinction. In modern Russian, the concept of Hell (Ад) is directly derived from Hades (Аид), separate and independent of Gehenna. Fire imagery is attributed primarily to Gehenna, which is most commonly mentioned as Gehenna the Fiery (Геенна огненная), and appears to be synonymous to the lake of fire.

- The New World Translation, used by Jehovah's Witnesses, maintains a distinction between Gehenna and Hades by transliterating Gehenna, and by rendering "Hades" (or "Sheol") as "the Grave". Earlier editions left all three names untranslated.

- The word "hell" is not used in the New American Bible,[45] except in a footnote in the book of Job translating an alternative passage from the Vulgate, in which the word corresponds to Jerome's "inferos," itself a translation of "sheol." "Gehenna" is untranslated, "Hades" either untranslated or rendered "netherworld," and "sheol" rendered "nether world."

Translations without a distinction:

- The late tenth century Wessex Gospels and the 14th century Wycliffe Bible render both the Latin inferno and gehenna as Hell.

- The 16th century Tyndale and later translators had access to the Greek, but Tyndale translated both Gehenna and Hades as same English word, Hell.

- The 17th century King James Version of the Bible is the only English translation in modern use to translate Sheol, Hades, and Gehenna by calling them all "Hell."

Some Christians consider Gehenna to be a place of eternal conscious punishment.[46] Some other Christians, however, imagine Gehenna to be a place where sinners are tormented for a limited amount of time until they are eventually destroyed, soul and body. Some other Christians believe that Gehenna is a metaphor for complete destruction of soul and body, and that those who are "cast" into it will not experience any torment; they will just cease to exist. Some Christian scholars, however, have suggested that Gehenna may be a different type of metaphor, a prophetic one for the horrible fate that awaited the many civilians killed in the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE.[47][48]

Islam

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2024) |

The name given to Hell in Islam, Jahannam, directly derives from Gehenna.[49] The Quran contains 77 references to the Islamic interpretation of Gehenna (جهنم), but does not mention Sheol / Hades as the "abode of the dead", and instead uses the word "Qabr" (قبر, meaning grave).

See also

[edit]- Araf (Islam)

- Christian views on Hell

- Heaven in Judaism

- Heaven in Christianity

- Jahannam, the realm of punishment for the evil in Islam

- Jannah, the final abode of the righteous in Islam

- Jewish eschatology

- Hell in the arts and popular culture

- Matarta

- Outer darkness, New Testament term

- Purgatory

- Spirit world (Latter Day Saints)

- Spirits in prison, New Testament term

- Tzoah Rotachat, location in Gehenna (Gehinnom) where the souls of Jews who committed certain sins are sent for punishment

- World of Darkness (Mandaeism)

- World of Light

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Watson E. Mills; Roger Aubrey Bullard (1990). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7.

- ^ Kohler, Kaufmann; Ludwig Blau (1906). "Gehenna". Jewish Encyclopedia. "The place where children were sacrificed to the god Moloch was originally in the 'valley of the son of Hinnom,' to the south of Jerusalem (Joshua 15:8, passim; II Kings 23:10; Jeremiah 2:23; 7:31–32; 19:6, 13–14). For this reason the valley was deemed to be accursed, and 'Gehenna' therefore soon became a figurative equivalent for 'hell.'"

- ^ Kohler, Kaufmann; Ludwig Blau (1906). "Gehenna: Sin and Merit" Jewish Encyclopedia: "It is frequently said that certain sins will lead man into Gehenna. The name 'Gehenna' itself is explained to mean that unchastity will lead to Gehenna ('Er. 19a); so also will adultery, idolatry, pride, mockery, hypocrisy, anger, etc. (Soṭah 4b, 41b; Ta'an. 5a; B. B. 10b, 78b; 'Ab. Zarah 18b; Ned. 22a)."

"Hell". Catholic Encyclopedia: "[I]n the New Testament the term Gehenna is used more frequently in preference to hades, as a name for the place of punishment of the damned.... [The Valley of Hinnom was] held in abomination by the Jews, who, accordingly, used the name of this valley to designate the abode of the damned (Targ. Jon., Gen., iii, 24; Henoch, c. xxvi). And Christ adopted this usage of the term." - ^ a b Trachtenberg, Joshua (2004) [Originally published 1939]. Jewish Magic and Superstition. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 66. ISBN 9780812218626.

- ^ Masterman, Ernest W. G. "Hinnom, Valley of". International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 July 2021 – via InternationalStandardBible.com.

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: 2 Chronicles 28:3 - New International Version". Bible Gateway.

- ^ "Bible Gateway passage: 2 Chronicles 28:3 - English Standard Version". Bible Gateway.

- ^ Jones, Daniel; Roach, Peter, James Hartman and Jane Setter, eds. Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. 17th edition. Cambridge UP, 2006.

- ^ Smith, G. A. 1907. Jerusalem: The Topography, Economics and History from the Earliest Times to A.D. 70, pages 170-180. London.

- ^ Dalman, G. 1930. Jerusalem und sein Gelande. Schriften des Deutschen Palastina-Instituts 4

- ^ Bailey, L. R. 1986. Gehenna: The Topography of Hell. BA 49: 187

- ^ Watson, Duane F. Hinnom. In Freedman, David Noel, ed., The Anchor Bible Dictionary, New York Doubleday 1997, 1992.

- ^ Geoffrey W. Bromiley, International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: "E–J." 1982.

- ^ Geoffrey W. Bromiley International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Q–Z, 1995 p. 259 "Stager and Wolff have convincingly demonstrated that child sacrifice was practiced in Phoenecian Carthage (Biblical Archaeology Review, 10 [1984], 30–51). At the sanctuary called Tophet, children were sacrificed to the goddess Tank and her .."

- ^ Hays 2011 "..(Lev 18:21–27; Deut 12:31; 2 Kgs 16:3; 21:2), and there is indeed evidence for child sacrifice in ancient Syria-Palestine." [Footnote:] "Day, Molech, 18, esp. n. 11. See also A. R. W. Green, The Role of Human Sacrifice in the Ancient Near East (SBLDS 1; Missoula, Mont.: Scholars Press, 1975)."

- ^ P. Mosca, 'Child Sacrifice in Canaanite and Israelite Religion: A Study on Mulk and "pa' (PhD dissertation. Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, 1975)

- ^ Susan Niditch War in the Hebrew Bible: A Study in the Ethics of Violence 1995 p. 48 "An ancient Near Eastern parallel for the cult of Molech is provided by Punic epigraphic and archaeological evidence (Heider:203)

- ^ "Jeremiah 19:4 Context: Because they have forsaken me, and have estranged this place, and have burned incense in it to other gods, that they didn't know, they and their fathers and the kings of Judah; and have filled this place with the blood of innocents".

- ^ (J. Day:83; Heider:405; Mosca: 220, 228), ... Many no doubt did as Heider allows (269, 272, 406) though J. Day denies it (85). ... Heider and Mosca conclude, in fact, that a form of child sacrifice was a part of state-sponsored ritual until the reform of the ..."

- ^ Richard S. Hess, Gordon J. Wenham Zion, City of Our God. 1999, p. 182 "The sacrifices of children and the cult of Molech are associated with no other place than the Hinnom Valley. ... of Jerusalem, the Jebusites (brackets mine). As yet, no trace has been located through archaeological search in Ben- Hinnom or in the Kidron Valley. ... Carthage was found in an area of Tunis that has had little occupation on the site to eradicate the evidence left of a cult of child sacrifice there."

- ^ Christopher B. Hays Death in the Iron Age II & in First Isaiah 2011 p. 181 "Efforts to show that the Bible does not portray actual child sacrifice in the Molek cult, but rather dedication to the god by fire, have been convincingly disproved. Child sacrifice is well attested in the ancient world, especially in times of crisis."

- ^ Gabriel Barkay, "The Riches of Ketef Hinnom." Biblical Archaeological Review 35:4–5 (2005): 22–35, 122–26.

- ^ McNamara, Targums and Testament, ISBN 978-0716506195

- ^ Targum Yonatan, Isaiah 66:24

- ^ "Gehinnom". Judaism 101.

Gehinnom is the Hebrew name; Gehenna is Yiddish.

- ^ "Hell". Judaism 101.

The place of spiritual punishment and/or purification for the wicked dead in Judaism is not referred to as Hell, but as Gehinnom or She'ol.

- ^ "Judaism 101: Olam Ha-Ba: The Afterlife".

- ^ e.g. Mishnah Kiddushin 4.14, Avot 1.5, 5.19, 20; Tosefta Berachot 6.15; Babylonian Talmud Rosh Hashanah 16b:7a, Berachot 28b

- ^ Hebrew visions of Hell and Paradise

- ^ Legends of the Jews Vol 4 pp.42-43

- ^ Tosefta Sanhedrin 13:5

- ^ Bava Metzia 58b

- ^ Radak, Psalms 27:13

- ^ Lloyd R. Bailey, "Gehenna: The Topography of Hell," Biblical Archeologist 49 [1986]: 189

- ^ Hermann L. Strack and Paul Billerbeck, Kommentar zum Neuen Testament aus Talmud and Midrasch, 5 vols. [Munich: Beck, 1922–56], 4:2:1030

- ^ Maimonides’ Introduction to Perek Helek, ed. and transl. by Maimonides Heritage Center, p. 3–4.

- ^ Maimonides’ Introduction to Perek Helek, ed. and transl. by Maimonides Heritage Center, pp. 22–23.

- ^ "Torah of Yeshuah: Book of Meqabyan I - III". July 11, 2015.

- ^ "Blue Letter Bible. "Dictionary and Word Search for geenna (Strong's 1067)"". Archived from the original on 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- ^ "G5590 – psychē – Strong's Greek Lexicon (NKJV)". Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "G1067 – geenna – Strong's Greek Lexicon (KJV)". Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ "Translations for 2Pe 2:4". Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Murdoch & Read (2004) Early Germanic Literature and Culture, p. 160. [1]

- ^ "YLT Search Results for "hell"". Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ "BibleGateway – hell [search] – New American Bible (Revised Edition) (NABRE), 4th Edition". Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Metzger & Coogan (1993) Oxford Companion to the Bible, p. 243.

- ^ Gregg, Steve (2013). All You Want to Know About Hell. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson. pp. 86–98. ISBN 978-1401678302.

- ^ Wright, N. T. (1996). Jesus and the Victory of God: Christian Origins and the Question of God, Volume 2. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. pp. 454–55, fn. #47. ISBN 978-0281047178.

- ^ Richard P. Taylor (2000). Death and the Afterlife: A Cultural Encyclopedia. "JAHANNAM From the Hebrew ge-hinnom, which refers to a valley outside Jerusalem, Jahannam is the Islamic word for hell."

Sources

[edit] This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hyvernat, Henry; Kohler, Kaufmann (1901–1906). "ABSALOM ("The Father of Peace")". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hyvernat, Henry; Kohler, Kaufmann (1901–1906). "ABSALOM ("The Father of Peace")". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

External links

[edit]- Short guide to today's Valley of Hinnom, with biblical story

- Columbia Encyclopedia on the Valley of Hinnom

- Biblical Proper Names on the Valley of Hinnom

- Gehenna from the 1901–1906 Jewish Encyclopedia

- The Jewish view of Hell on chabad.org

- Olam Ha-Ba: The Afterlife Judaism 101

- What Is Gehenna? Archived 2016-07-16 at the Wayback Machine Ariela Pelaia, About religion, about.com

- What is Gehenna Like?: Rabbinic Descriptions of Gehenna Archived 2016-07-16 at the Wayback Machine Ariela Pelaia, About religion, about.com

- A Christian Universalist perspective from Tentmaker.org

- A Christian Conditionalist perspective on Gehenna from Afterlife.co.nz