Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Vulgate

View on Wikipedia

The Vulgate (/ˈvʌlɡeɪt, -ɡət/)[a] is a late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible. It is largely the work of Saint Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Vetus Latina Gospels used by the Roman Church. Later, of his own initiative, Jerome extended this work of revision and translation to include most of the books of the Bible.

The Vulgate became progressively adopted as the Bible text within the Western Church. Over succeeding centuries, it eventually eclipsed the Vetus Latina texts.[1] By the 13th century it had taken over from the former version the designation versio vulgata (the "version commonly used"[2]) or vulgata for short.[3] The Vulgate also contains some Vetus Latina translations that Jerome did not work on.[4]

The Catholic Church affirmed the Vulgate as its official Latin Bible at the Council of Trent (1545–1563), though there was no single authoritative edition of the book at that time in any language.[5] The Vulgate did eventually receive an official edition to be promulgated among the Catholic Church as the Sixtine Vulgate (1590), then as the Clementine Vulgate (1592), and then as the Nova Vulgata (1979). The Vulgate is still currently used in the Latin Church. The Clementine edition of the Vulgate became the standard Bible text of the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church, and remained so until 1979 when the Nova Vulgata was promulgated.

Terminology

[edit]The earliest known use of the term Vulgata to describe Jerome's "new" Latin translation was made by Roger Bacon in the 13th century.[6]

The term Vulgate was used in a 1538 edition Latin Bible by Robert Estienne which coupled the popular (i.e. the Vulgate) with the "most improved" (i.e., the recent new Latin translations of Pagninus, Beza and Baduell): Biblia utriusque testamenti juxta vulgatam translationem et eam, quam haberi potut, emendatissimam.[7]

Authorship

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

While the majority of the Vulgate's translation is traditionally attributed to Jerome, the Vulgate has a compound text that is not entirely Jerome's work.[8] Jerome's translation of the four Gospels are revisions of Vetus Latina translations he did while having the Greek as reference.[9][10]

The Latin translations of the rest of the New Testament are revisions to Vetus Latina texts, considered as being made by Pelagian circles or by Rufinus the Syrian, or by Rufinus of Aquileia.[9][11][12] Several unrevised (deuterocanonical or non-canonical) books from Vetus Latina Old Testaments also commonly became included in the Vulgate. These are: 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach or Ecclesiasticus, Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah.[13][14]

Having separately translated the book of Psalms from the Greek Hexapla Septuagint, Jerome translated all of the books of the Jewish Bible—the Hebrew book of Psalms included—from Hebrew himself. He also translated the books of Tobit and Judith from Aramaic versions, the additions to the Book of Esther from the Common Septuagint and the additions to the Book of Daniel from the Greek of Theodotion.[15]

Content

[edit]The Vulgate is "a composite collection which cannot be identified with only Jerome's work," because the Vulgate contains Vetus Latina texts which are independent from Jerome's work.[13]

A famous historical edition of the Vulgate, the Alcuinian pandects from the end of the 700s, contains:[13]

- New Testament

- Revision of Vetus Latina by Jerome: the Gospels, corrected with reference to the Greek manuscripts which Jerome considered the best available.[16][13]

- Revision of Vetus Latina perhaps by Rufinus the Syrian, or by Rufinus of Aquileia or by so-called Pelagian groups: Acts, Pauline epistles, Catholic epistles, and the Apocalypse.[9][12][11]

- Old Testament

- Translation from the Hebrew by Jerome: all the books from the Hebrew canon except the Book of Psalms.[13]

- Translation from the Hexaplar Septuagint by Jerome: his Gallican version of the Book of Psalms.[9]

- Deuterocanonicals and non-canonicals

- Translation from Aramaic by Jerome: the book of Tobit and the book of Judith.[13]

- Translation from the Greek of Theodotion by Jerome: the three additions to the Book of Daniel: the Song of the Three Children, the Story of Susanna, and the Story of Bel and the Dragon. Jerome marked these additions with an obelus before them to distinguish them from the rest of the text.[17] He says that because those parts "are spread throughout the whole world, [we] have appended by banishing and placing them after the spit (or "obelus"), so we will not be seen among the unlearned to have cut off a large part of the scroll."[18]

- Translation from the Common Septuagint by Jerome: the Additions to Esther. Jerome gathered all these additions together at the end of the Book of Esther, marking them with an obelus.[19]

- Vetus Latina, wholly unrevised: Epistle to the Laodiceans, Sirach, Wisdom, 1 and 2 Maccabees.[13][14] The 13th-century Paris Bibles remove the Epistle to the Laodiceans, but add:[13]

- Vetus Latina, wholly unrevised: Prayer of Manasses, 4 Ezra, the Book of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah. The Book of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah were first excluded by Jerome as non-canonical, but sporadically included in Vulgate Bibles from the 9th century onward.[13][14]

- Independent translation, distinct from the Vetus Latina (probably of the 3rd century): 3 Ezra a.k.a. 1 Esdras.[13][20]

Jerome is connected to three different Latin versions of the Psalms, which were adopted in different Vulgate editions, regions or uses:

- Versio Romana formerly attributed to Jerome (384): a revision of the earlier vetus latina. It is still sung in Catholic Latin liturgies, in the Roman Missal.

- Versio Gallicana by Jerome (386-389): a translation of the Psalms from the Greek Hexapla became the most common version in Bibles.

- Versio juxta Hebraicum by Jerome (c.390 to 398):[21] a translation of the Psalms from the Hebrew.[15] This translation of the Psalms was kept in Spanish manuscripts of the Vulgate long after the Gallican psalter had supplanted it elsewhere.[22]

Jerome's work of translation

[edit]

Jerome did not embark on the work with the intention of creating a new version of the whole Bible, but the changing nature of his program can be tracked in his voluminous correspondence.

He had been commissioned by Damasus I in 382 to revise the Vetus Latina text of the four Gospels from the best Greek texts.[23] By the time of Damasus' death in 384, Jerome had completed this task, together with a more cursory revision from the Greek Common Septuagint of the Vetus Latina text of the Psalms in the Roman Psalter, a version which he later disowned and is now lost.[24] How much of the rest of the New Testament he then revised is difficult to judge,[25][26] but none of his work survived in the Vulgate text of these books.

The revised text of the New Testament outside the Gospels is deemed the work of other scholars. Rufinus of Aquileia has been suggested, as has Rufinus the Syrian (an associate of Pelagius) and Pelagius himself, though without specific evidence for any of them;[11][27] Pelagian groups have also been suggested as the revisers.[9] This unknown reviser worked more thoroughly than Jerome had done, consistently using older Greek manuscript sources of Alexandrian text-type. They had published a complete revised New Testament text by 410 at the latest, when Pelagius quoted from it in his commentary on the letters of Paul.[28][10]

In Jerome's Vulgate, the Hebrew Book of Ezra–Nehemiah is translated as the single book of "Ezra". Jerome defends this in his Prologue to Ezra, although he had noted formerly in his Prologue to the Book of Kings that some Greeks and Latins had proposed that this book should be split in two. Jerome argues that the two books of Ezra found in the Septuagint and Vetus Latina, Esdras A and Esdras B, represented "variant examples" of a single Hebrew original. Hence, he does not translate Esdras A separately even though up until then it had been universally found in Greek and Vetus Latina Old Testaments, preceding Esdras B, the combined text of Ezra–Nehemiah.[29]

The Vulgate is usually credited as being the first translation of the Old Testament into Latin directly from the Hebrew Tanakh rather than from the Greek Septuagint. Jerome's extensive use of exegetical material written in Greek, as well as his use of the Aquiline and Theodotiontic columns of the Hexapla, along with the somewhat paraphrastic style[30] in which he translated, makes it difficult to determine exactly how direct the conversion of Hebrew to Latin was.[b][31][32]

Augustine of Hippo, a contemporary of Jerome, states in Book XVII ch. 43 of his The City of God that "in our own day the priest Jerome, a great scholar and master of all three tongues, has made a translation into Latin, not from Greek but directly from the original Hebrew."[33] Nevertheless, Augustine still maintained that the Septuagint, alongside the Hebrew, witnessed the inspired text of Scripture. He reminded Jerome of the need for the Latin church to be in sync with the Greek church, and practical difficulty in finding any Hebrew-reading Christian scholar who could check Jerome's translation from the Hebrew.[34] He consequently pressed Jerome for complete copies of his Hexaplar Latin translation of the Old Testament, a request that Jerome ducked with the excuses that scribes were in short supply and that the originals had been lost "through someone's dishonesty".[35]

He used a novel layout technique per cola et commata which put each major clause on new line.[36]

Prologues

[edit]Prologues written by Jerome to some of his translations of parts of the Bible are to the Pentateuch,[37] to Joshua,[38] and to Kings (1–2 Kings and 1–2 Samuel) which is also called the Galeatum principium.[39] Following these are prologues to Chronicles,[40] Ezra,[41] Tobit,[42] Judith,[43] Esther,[44] Job,[45] the Gallican Psalms,[46] Song of Songs,[47] Isaiah,[48] Jeremiah,[49] Ezekiel,[50] Daniel,[18] the minor prophets,[51] the gospels.[52] The final prologue is to the Pauline epistles and is better known as Primum quaeritur; this prologue is considered not to have been written by Jerome.[53][11] Related to these are Jerome's Notes on the Rest of Esther[54] and his Prologue to the Hebrew Psalms.[55]

A theme of the Old Testament prologues is Jerome's preference for the Hebraica veritas (i.e., Hebrew truth) over the Septuagint, a preference which he defended from his detractors. After Jerome had translated some parts of the Septuagint into Latin, he came to consider the text of the Septuagint as being faulty in itself, i.e. Jerome thought mistakes in the Septuagint text were not all mistakes made by copyists, but that some mistakes were part of the original text itself as it was produced by the Seventy translators. Jerome believed that the Hebrew text more clearly prefigured Christ than the Greek of the Septuagint, since he believed some quotes of the Old Testament in the New Testament were not present in the Septuagint, but existed in the Hebrew version; Jerome gave some of those quotes in his prologue to the Pentateuch.[56] In the Galeatum principium (a.k.a. Prologus Galeatus), Jerome described an Old Testament canon of 22 books, which he found represented in the 22-letter Hebrew alphabet. Alternatively, he numbered the books as 24, which he identifies with the 24 elders in the Book of Revelation casting their crowns before the Lamb.[39] In the prologue to Ezra, he sets the "twenty-four elders" of the Hebrew Bible against the "Seventy interpreters" of the Septuagint.[41]

In addition, many medieval Vulgate manuscripts included Jerome's epistle number 53, to Paulinus bishop of Nola, as a general prologue to the whole Bible. Notably, this letter was printed at the head of the Gutenberg Bible. Jerome's letter promotes the study of each of the books of the Old and New Testaments listed by name (and excluding any mention of the deuterocanonical books); and its dissemination had the effect of propagating the belief that the whole Vulgate text was Jerome's work.

The prologue to the Pauline Epistles in the Vulgate defends the Pauline authorship of the Epistle to the Hebrews, directly contrary to Jerome's own views—a key argument in demonstrating that Jerome did not write it. The author of the Primum quaeritur is unknown, but it is first quoted by Pelagius in his commentary on the Pauline letters written before 410. As this work also quotes from the Vulgate revision of these letters, it has been proposed that Pelagius or one of his associates may have been responsible for the revision of the Vulgate New Testament outside the Gospels. At any rate, it is reasonable to identify the author of the preface with the unknown reviser of the New Testament outside the gospels.[11]

Some manuscripts of the Pauline epistles contain short Marcionite prologues to each of the epistles indicating where they were written, with notes about where the recipients dwelt. Adolf von Harnack, citing De Bruyne, argued that these notes were written by Marcion of Sinope or one of his followers.[57] Many early Vulgate manuscripts contain a set of Priscillianist prologues to the gospels.

Relation with the Vetus Latina Bible

[edit]The Latin biblical texts in use before Jerome's Vulgate are usually referred to collectively as the Vetus Latina, or "Vetus Latina Bible". "Vetus Latina" means that they are older than the Vulgate and written in Latin, not that they are written in Old Latin. Jerome, in his preface to the Vulgate gospels, commented that there were "as many [translations] as there are manuscripts"; subsequently noting the same in his preface to the Book of Joshua.

The translations in the Vetus Latina had accumulated piecemeal over a century or more. They were not translated by a single person or institution, nor uniformly edited. The individual books varied in quality of translation and style, and different manuscripts and quotations witness wide variations in readings. Some books appear to have been translated several times.

The Vulgate did not immediately supersede the Vetus Latina translations. Pandects from the Early Middle Ages sometimes had some books (e.g. deuterocanonicals, Acts, Revelation), or took phrases, or had glosses from the Vetus Latina, but this declined through the High Middle Ages.[58]

New Testament

[edit]Jerome's work on the Gospels was a revision of the Vetus Latina versions, and not an entirely new translation. The base text for Jerome's revision of the gospels was a Vetus Latina text similar to the Codex Veronensis, with the text of the Gospel of John conforming more to that in the Codex Corbiensis.[59]

The Vetus Latina gospels had been translated from Greek originals of the Western text-type. Comparison of Jerome's Gospel texts with those in Vetus Latina witnesses, suggests that his revision was concerned with substantially redacting their expanded "Western" phraseology in accordance with the Greek texts of better early Byzantine and Alexandrian witnesses. For the Gospels "High priest" is rendered princeps sacerdotum in Vulgate Matthew; as summus sacerdos in Vulgate Mark; and as pontifex in Vulgate John.

In places Jerome adopted readings that did not correspond to a straightforward rendering either of the Vetus Latina or the Greek text, so reflecting a particular doctrinal interpretation; as in his rewording panem nostrum supersubstantialem at Matthew 6:11.[60]

One major change Jerome introduced was to re-order the Latin Gospels. Most Vetus Latina gospel books followed the "Western" order of Matthew, John, Luke, Mark; Jerome adopted the "Greek" order of Matthew, Mark, Luke, John. His revisions became progressively less frequent and less consistent in the gospels presumably done later.[61]

The unknown reviser of the rest of the New Testament shows marked differences from Jerome, both in editorial practice and in their sources. Where Jerome sought to correct the Vetus Latina text with reference to the best recent Greek manuscripts, with a preference for those conforming to the Byzantine text-type, the Greek text underlying the revision of the rest of the New Testament demonstrates the Alexandrian text-type found in the great uncial codices of the mid-4th century, most similar to the Codex Sinaiticus. The reviser's changes generally conform very closely to this Greek text, even in matters of word order—to the extent that the resulting text may be only barely intelligible as Latin.[10]

Old Testament

[edit]Jerome himself uses the term "Latin Vulgate" for the Vetus Latina text, so intending to denote this version as the common Latin rendering of the Greek Vulgate or Common Septuagint (which Jerome otherwise terms the "Seventy interpreters"). This remained the usual use of the term "Latin Vulgate" in the West for centuries. On occasion Jerome applies the term "Septuagint" (Septuaginta) to refer to the Hexaplar Septuagint, where he wishes to distinguish this from the Vulgata or Common Septuagint.

According to Old Testament scholar Amanda Benckhuysen: "Jerome omits from the Vulgate the phrase “who was with her” in Genesis 3:6, making Eve doubly culpable for the fall and responsible for Adam’s sin. By implying Adam’s absence during the serpent’s conversation with Eve, the Vulgate portrays Eve as the seduced who becomes the seducer, beguiling a naive Adam to eat the forbidden fruit."[62]

Psalter

[edit]The Book of Psalms, in particular, had circulated for over a century in an earlier Latin version (the Cyprianic Version), before it was superseded by the Vetus Latina version in the 4th century.

After the Gospels, the most widely used and copied part of the Christian Bible is the Book of Psalms. Consequently, Damasus also commissioned Jerome to revise the psalter in use in Rome, to agree better with the Greek of the Common Septuagint. Jerome said he had done this cursorily when in Rome, but he later disowned this version, maintaining that copyists had reintroduced erroneous readings. Until the 20th century, it was commonly assumed that the surviving Roman Psalter represented Jerome's first attempted revision, but more recent scholarship—following de Bruyne—rejects this identification. The Roman Psalter is indeed one of at least five revised versions of the mid-4th century Vetus Latina Psalter, but compared to the other four, the revisions in the Roman Psalter are in clumsy Latin, and fail to follow Jerome's known translational principles, especially in respect of correcting harmonised readings. Nevertheless, it is clear from Jerome's correspondence (especially in his defence of the Gallican Psalter in the long and detailed Epistle 106)[63] that he was familiar with the Roman Psalter text, and consequently it is assumed that this revision represents the Roman text as Jerome had found it.[64]

Deuterocanonials

[edit]Wisdom, Sirach or Ecclesiasticus, 1 and 2 Maccabees and Baruch (with the Letter of Jeremiah) are included in the Vulgate, and are purely Vetus Latina translations which Jerome did not touch.[65]

In the 9th century the Vetus Latina texts of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah were introduced into the Vulgate in versions revised by Theodulf of Orleans and are found in a minority of early medieval Vulgate pandect bibles from that date onward.[14] After 1300, when the booksellers of Paris began to produce commercial single volume Vulgate bibles in large numbers, these commonly included both Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah as the Book of Baruch. Also beginning in the 9th century, Vulgate manuscripts are found that split Jerome's combined translation from the Hebrew of Ezra and the Nehemiah into separate books called 1 Ezra and 2 Ezra. Bogaert argues that this practice arose from an intention to conform the Vulgate text to the authoritative canon lists of the 5th/6th century, where 'two books of Ezra' were commonly cited.[66] Subsequently, many late medieval Vulgate bible manuscripts introduced a Latin version, originating from before Jerome and distinct from that in the Vetus Latina, of the Greek Esdras A, now commonly termed 3 Ezra; and also a Latin version of an Ezra Apocalypse, commonly termed 4 Ezra.

Council of Trent and position of the Catholic Church

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

In the early 1500s numerous new Catholic and Protestant biblical translations or revisions in Latin appeared, and theological disputes had arisen over the canonical status of books which e.g. supported doctrines that Luther disagreed with. The Council of Trent (1545–1563) both finalized the biblical canon,[67] and re-endorsed the Vulgate among Latin versions for public reading: it was to "be held as authentic".[68] (In liturgical use, this was not the case: the Roman Missal uses Psalms and Pater Noster taken from the vetus latina Latin versions.)

The Council of Trent cited long usage in support of the Vulgate's magisterial authority:

Moreover, this sacred and holy Synod,—considering that no small utility may accrue to the Church of God, if it be made known which out of all the Latin editions, now in circulation, of the sacred books, is to be held as authentic,—ordains and declares, that the said old and vulgate edition, which, by the lengthened usage of so many years, has been approved of in the Church, be, in public lectures, disputations, sermons and expositions, held as authentic; and that no one is to dare, or presume to reject it under any pretext whatever.[68]

The qualifier "Latin editions, now in circulation" and the use of "authentic" (not "inerrant") show the limits of this statement.[69]

When the council listed the books included in the canon, it qualified the books as being "entire with all their parts, as they have been used to be read in the Catholic Church, and as they are contained in the Vetus Latina vulgate edition". The fourth session of the Council specified 72 canonical books in the Bible: 45 in the Old Testament, 27 in the New Testament with Lamentations not being counted as separate from Jeremiah.[70] On 2 June 1927, Pope Pius XI clarified this decree, allowing that the Comma Johanneum was open to dispute.[71]

Later, in the 20th century, Pope Pius XII declared the Vulgate as "free from error whatsoever in matters of faith and morals" in his encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu:

Hence this special authority or as they say, authenticity of the Vulgate was not affirmed by the Council particularly for critical reasons, but rather because of its legitimate use in the Churches throughout so many centuries; by which use indeed the same is shown, in the sense in which the Church has understood and understands it, to be free from any error whatsoever in matters of faith and morals; so that, as the Church herself testifies and affirms, it may be quoted safely and without fear of error in disputations, in lectures and in preaching [...]"[72]

— Pope Pius XII

The inerrancy is with respect to faith and morals, as it says in the above quote: "free from any error whatsoever in matters of faith and morals", and the inerrancy is not in a philological sense:

[...] and so its authenticity is not specified primarily as critical, but rather as juridical.[72]

The Catholic Church has produced three official editions of the Vulgate: the Sixtine Vulgate, the Clementine Vulgate, and the Nova Vulgata (see below).

Variants

[edit]As with the vetus latina and the Greek text types, manuscript versions of the Vulgate texts exhibit a considerable number of minor variations by scribes. Regular attempts were made over the centuries to conserve Jerome's text or to purify the text of obvious errors or substitutions from vetus latina phrases: attempts such as by Cassiodorus in the 6th century, Alcuin in the 8th, Stephen Harding in the 12th, Erasmus in the 16th, to the modern Stuttgart Vulgate.[73]

Scholars have identified families of variants, allowing tracing of influence or provenance of texts: for example, the Latin text of the Rushworth gospels belongs to the Insular or Irish family with characteristic inversions of word order.[74]: xlv

Influence on Western Christianity

[edit]

For over a thousand years (c. AD 400–1530), the Vulgate was the most commonly used edition of the most influential text in Western European society. Indeed, for most Western Christians, especially Catholics, it was the only version of the Bible as a publication ever encountered, only truly being eclipsed in the mid-20th century.[75]

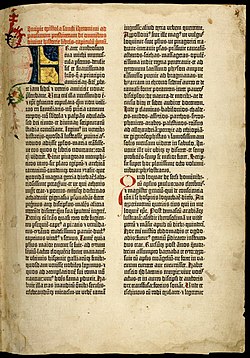

In about 1455, the first Vulgate published by the moveable type process was produced in Mainz by a partnership between Johannes Gutenberg and banker John Fust (or Faust).[76][77][78] At the time, a manuscript of the Vulgate was selling for approximately 500 guilders. Gutenberg's works appear to have been a commercial failure, and Fust sued for recovery of his 2026 guilder investment and was awarded complete possession of the Gutenberg plant. Arguably, the Reformation could not have been possible without the diaspora of biblical knowledge that was permitted by the development of moveable type.[77]

Aside from its use in prayer, liturgy, and private study, the Vulgate served as inspiration for ecclesiastical art and architecture, hymns, countless paintings, and popular mystery plays.

Reformation

[edit]The fifth volume of Walton's London Polyglot of 1657 included several versions of the New Testament: in Greek, Latin (a Vulgate version and the version by Arius Montanus), Syriac, Ethiopic, and Arabic. It also included a version of the Gospels in Persian.[79]

The Vulgate Latin is used regularly in Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan of 1651; in the Leviathan Hobbes "has a worrying tendency to treat the Vulgate as if it were the original".[80]

Translations

[edit]Before the publication of Pius XII's Divino afflante Spiritu, the Vulgate was the source text used for many translations of the Bible into vernacular languages. In English, the interlinear translation of the Lindisfarne Gospels[81] as well as other Old English Bible translations, the translation of John Wycliffe,[82] the Douay–Rheims Bible, the Confraternity Bible, and Ronald Knox's translation were all made from the Vulgate.

Influence upon the English language

[edit]The Vulgate had significant cultural influence on literature for centuries, and thus the development of the English language, especially in matters of religion.[75] Many Latin words were taken from the Vulgate into English nearly unchanged in meaning or spelling: creatio (e.g. Genesis 1:1, Heb 9:11), salvatio (e.g. Is 37:32, Eph 2:5), justificatio (e.g. Rom 4:25, Heb 9:1), testamentum (e.g. Mt 26:28), sanctificatio (1 Ptr 1:2, 1 Cor 1:30), regeneratio (Mt 19:28), and raptura (from a noun form of the verb rapere in 1 Thes 4:17). The word "publican" comes from the Latin publicanus (e.g., Mt 10:3), and the phrase "far be it" is a translation of the Latin expression absit. (e.g., Mt 16:22 in the King James Bible).[83] Other examples include apostolus, ecclesia, evangelium, Pascha, and angelus.

Critical value

[edit]In translating the 38 books of the Hebrew Bible (Ezra–Nehemiah being counted as one book), Jerome was relatively free in rendering their text into Latin. Paleographer Frederic Kenyon notes that "the translation is of unequal merit; some parts are free to the verge of paraphrase, others are so literal as to be unintelligible."[84]

Jerome's translation has been regarded by scholars as very useful for reconstructing the state of the Hebrew text as it existed at his time, that being quite close to the Masoretic consonantal Hebrew text version compiled nearly 600 years after Jerome.[84]

Manuscripts and editions

[edit]The Vulgate exists in many forms. The Codex Amiatinus is the oldest surviving complete manuscript from the 8th century. The Gutenberg Bible is a notable printed edition of the Vulgate by Johann Gutenberg in 1455. The Sixtine Vulgate (1590) is the first official Bible of the Catholic Church. The Clementine Vulgate (1592) is a standardized edition of the medieval Vulgate, and the second official Bible of the Catholic Church. The Stuttgart Vulgate is a 1969 critical edition of the Vulgate. The Nova Vulgata is the third and latest official Bible of the Catholic Church; it was published in 1979, and is a translation from modern critical editions of original language texts of the Bible.

Manuscripts and early editions

[edit]

A number of manuscripts containing or reflecting the Vulgate survive today. Dating from the 8th century, the Codex Amiatinus is the earliest surviving manuscript of the complete Vulgate Bible. The Codex Fuldensis, dating from around 545, contains most of the New Testament in the Vulgate version, but the four gospels are harmonised into a continuous narrative derived from the Diatessaron.

Carolingian period

[edit]"The two best-known revisions of the Latin Scriptures in the early medieval period were made in the Carolingian period by Alcuin of York (c. 730–840) and Theodulf of Orleans (750/760–821)."[85]

Alcuin of York oversaw efforts to make a Latin Bible, an exemplar of which was presented to Charlemagne in 801. Alcuin's edition contained the Vulgate version. It appears Alcuin concentrated only on correcting errors of grammar, orthography and punctuation. "Even though Alcuin's revision of the Latin Bible was neither the first nor the last of the Carolingian period, it managed to prevail over the other versions and to become the most influential edition for centuries to come." The success of this Bible has been attributed to the fact that this Bible may have been "prescribed as the official version at the emperor's request." However, Bonifatius Fischer believes its success was rather due to the productivity of the scribes of Tours where Alcuin was abbot, at the monastery of Saint Martin; Fischer believes the emperor only favored the editorial work of Alcuin by encouraging work on the Bible in general.[86]

"Although, in contrast to Alcuin, Theodulf [of Orleans] clearly developed an editorial programme, his work on the Bible was far less influential than that of hs slightly older contemporary. Nevertheless, several manuscripts containing his version have come down to us." Theodulf added to his edition of the Bible the Book of Baruch, which Alcuin's edition did not contain; it is this version of the Book of Baruch which later became part of the Vulgate. In his editorial activity, on at least one manuscript of the Theodulf Bible (S Paris, BNF lat. 9398), Theodulf marked variant readings along with their sources in the margin of the manuscripts. Those marginal notes of variant readings along with their sources "seem to foreshadow the thirteenth-century correctoria."[87] In the 9th century the Vetus Latina texts of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah were introduced into the Vulgate in versions revised by Theodulf of Orleans and are found in a minority of early medieval Vulgate pandect bibles from that date onward.[14]

Cassiodorus, Isidore of Sevilla, and Stephen Harding also worked on editions of the Latin Bible. Isidore's edition as well as the edition of Cassiodorus "ha[ve] not come down to us."[88]

By the 9th century, due to the success of Alcuin's edition, the Vulgate had replaced the Vetus Latina as the most available edition of the Latin Bible.[89]

Late Middle Ages

[edit]The University of Paris, the Dominicans, and the Franciscans assembled lists of correctoria—approved readings—where variants had been noted.[90]

Printed editions

[edit]Renaissance

[edit]Though the advent of printing greatly reduced the potential of human error and increased the consistency and uniformity of the text, the earliest editions of the Vulgate merely reproduced the manuscripts that were readily available to publishers. Of the hundreds of early editions, the most notable today is the Mazarin edition published by Johann Gutenberg and Johann Fust in 1455, famous for its beauty and antiquity. In 1504, the first Vulgate with variant readings was published in Paris. One of the texts of the Complutensian Polyglot was an edition of the Vulgate made from ancient manuscripts and corrected to agree with the Greek.

Erasmus published an edition corrected to agree better with the Greek and Hebrew in 1516. Other corrected editions were published by Xanthus Pagninus in 1518, Cardinal Cajetan, Augustinus Steuchius in 1529, Abbot Isidorus Clarius (Venice, 1542) and others. In 1528, Robertus Stephanus published the first of a series of critical editions, which formed the basis of the later Sistine and Clementine editions. John Henten's critical edition of the Bible followed in 1547.[6]

In 1550, Stephanus fled to Geneva, where he issued his final critical edition of the Vulgate in 1555. This was the first complete Bible with full chapter and verse divisions and became the standard biblical reference text for late-16th century Reformed theology.

Sixtine and Clementine Vulgates

[edit]

After the Reformation, when the Catholic Church strove to counter Protestantism and refute its doctrines, the Vulgate was declared at the Council of Trent to "be, in public lectures, disputations, sermons and expositions, held as authentic; and that no one is to dare, or presume to reject it under any pretext whatever."[68] Furthermore, the council expressed the wish that the Vulgate be printed quam emendatissime[c] ("with fewest possible faults").[5][91]

In 1590, the Sixtine Vulgate was issued, under Sixtus V, as being the official Bible recommended by the Council of Trent.[92][93] On 27 August 1590, Sixtus V died. After his death, "many claimed that the text of the Sixtine Vulgate was too error-ridden for general use."[94] On 5 September of the same year, the College of Cardinals stopped all further sales of the Sixtine Vulgate and bought and destroyed as many copies as possible by burning them. The reason invoked for this action was printing inaccuracies in Sixtus V's edition of the Vulgate. However, Bruce Metzger, an American biblical scholar, believes that the printing inaccuracies may have been a pretext and that the attack against this edition had been instigated by the Jesuits, "whom Sixtus had offended by putting one of Bellarmine's books on the 'Index' ".[95]

In the same year he became pope (1592), Clement VIII recalled all copies of the Sixtine Vulgate.[96][97] The reason invoked for recalling Sixtus V's edition was printing errors, however the Sixtine Vulgate was mostly free of them.[97][93]

The Sistine edition was replaced by Clement VIII (1592–1605). This new edition was published in 1592 and is called today the Clementine Vulgate[98][99] or Sixto-Clementine Vulgate.[99] "The misprints of this edition were partly eliminated in a second (1593) and a third (1598) edition."[98]

The Clementine Vulgate is the edition most familiar to Catholics who have lived prior to the liturgical reforms following Vatican II. Roger Gryson, in the preface to the 4th edition of the Stuttgart Vulgate (1994), asserts that the Clementine edition "frequently deviates from the manuscript tradition for literary or doctrinal reasons, and offers only a faint reflection of the original Vulgate, as read in the pandecta of the first millennium."[100] However, historical scholar Cardinal Francis Aidan Gasquet, in the Catholic Encyclopedia, states that the Clementine Vulgate substantially represents the Vulgate which Jerome produced in the 4th century, although "it stands in need of close examination and much correction to make it [completely] agree with the translation of St. Jerome".[101]

Modern critical editions

[edit]Most other later editions were limited to the New Testament and did not present a full critical apparatus, most notably Karl Lachmann's editions of 1842 and 1850 based primarily on the Codex Amiatinus and the Codex Fuldensis,[102] Fleck's edition[103] of 1840, and Constantin von Tischendorf's edition of 1864. In 1906 Eberhard Nestle published Novum Testamentum Latine,[104] which presented the Clementine Vulgate text with a critical apparatus comparing it to the editions of Sixtus V (1590), Lachman (1842), Tischendorf (1854), and Wordsworth and White (1889), as well as the Codex Amiatinus and the Codex Fuldensis.

To make a text available representative of the earliest copies of the Vulgate and summarise the most common variants between the various manuscripts, Anglican scholars at the University of Oxford began to edit the New Testament in 1878 (completed in 1954), while the Benedictines of Rome began an edition of the Old Testament in 1907 (completed in 1995). The Oxford Anglican scholars's findings were condensed into an edition of both the Old and New Testaments, first published at Stuttgart in 1969, created with the participation of members from both projects. These books are the standard editions of the Vulgate used by scholars.[105]

Oxford New Testament

[edit]As a result of the inaccuracy of existing editions of the Vulgate, in 1878, the delegates of the Oxford University Press accepted a proposal from classicist John Wordsworth to produce a critical edition of the New Testament.[106][107] This was eventually published as Nouum Testamentum Domini nostri Iesu Christi Latine, secundum editionem sancti Hieronymi in three volumes between 1889 and 1954.[108]

The edition, commonly known as the Oxford Vulgate, relies primarily on the texts of the Codex Amiatinus, Codex Fuldensis (Codex Harleianus in the Gospels), Codex Sangermanensis, Codex Mediolanensis (in the Gospels), and Codex Reginensis (in Paul).[109][110] It also consistently cites readings in the so-called DELQR group of manuscripts, named after the sigla it uses for them: Book of Armagh (D), Egerton Gospels (E), Lichfield Gospels (L), Book of Kells (Q), and Rushworth Gospels (R).[111]

Benedictine (Rome) Old Testament

[edit]In 1907, Pope Pius X commissioned the Benedictine monks to prepare a critical edition of Jerome's Vulgate, entitled Biblia Sacra iuxta latinam vulgatam versionem.[112] This text was originally planned as the basis for a revised complete official Bible for the Catholic Church to replace the Clementine edition.[113] The first volume, the Pentateuch, was completed in 1926.[114][115] For the Pentateuch, the primary sources for the text are the Codex Amiatinus, the Codex Turonensis (the Ashburnham Pentateuch), and the Ottobonianus Octateuch.[116] For the rest of the Old Testament (except the Book of Psalms) the primary sources for the text are the Codex Amiatinus and Codex Cavensis.[117]

Following the Codex Amiatinus and the Vulgate texts of Alcuin and Theodulf, the Benedictine Vulgate reunited the Book of Ezra and the Book of Nehemiah into a single book, reversing the decisions of the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate.

In 1933, Pope Pius XI established the Pontifical Abbey of St Jerome-in-the-City to complete the work. By the 1970s, as a result of liturgical changes that had spurred the Vatican to produce a new translation of the Latin Bible, the Nova Vulgata, the Benedictine edition was no longer required for official purposes,[118] and the abbey was suppressed in 1984.[119] Five monks were nonetheless allowed to complete the final two volumes of the Old Testament, which were published under the abbey's name in 1987 and 1995.[120]

Stuttgart Vulgate

[edit]

Based on the editions of Oxford and Rome, but with an independent examination of the manuscript evidence and extending their lists of primary witnesses for some books, the Württembergische Bibelanstalt, later the Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft (German Bible Society), based in Stuttgart, first published a critical edition of the complete Vulgate in 1969. The work has continued to be updated, with a fifth edition appearing in 2007.[121] The project was originally directed by Robert Weber, OSB (a monk of the same Benedictine abbey responsible for the Benedictine edition), with collaborators Bonifatius Fischer, Jean Gribomont, Hedley Frederick Davis Sparks (also responsible for the completion of the Oxford edition), and Walter Thiele. Roger Gryson has been responsible for the most recent editions. It is thus marketed by its publisher as the "Weber-Gryson" edition, but is also frequently referred to as the Stuttgart edition.[122]

The Weber-Gryson includes of Jerome's prologues and the Eusebian Canons.

It contains two Psalters, the Gallicanum and the juxta Hebraicum, which are printed on facing pages to allow easy comparison and contrast between the two versions. It has an expanded Apocrypha, containing Psalm 151 and the Epistle to the Laodiceans in addition to 3 and 4 Ezra and the Prayer of Manasses. In addition, its modern prefaces in Latin, German, French, and English are a source of valuable information about the history of the Vulgate.

Nova Vulgata

[edit]The Nova Vulgata (Nova Vulgata Bibliorum Sacrorum Editio), also called the Neo-Vulgate, is the official Latin edition of the Bible published by the Holy See for use in the contemporary Roman rite. It is not a critical edition of the historical Vulgate, but a revision of the text intended to accord with modern critical Hebrew and Greek texts and produce a style closer to Classical Latin.[123]

In 1979, the Nova Vulgata was promulgated as "typical" (standard) by John Paul II.[124]

Online versions

[edit]The title "Vulgate" is currently applied to three distinct online texts which can be found from various sources on the Internet. The text being used can be ascertained from the spelling of Eve's name in Genesis 3:20:[125][126]

- Heva: the Clementine Vulgate

- Hava: the Stuttgart edition of the Vulgate

- Eva: the Nova Vulgata

See also

[edit]Related articles

[edit]- Bible translations into Latin

- Biblia Pauperum

- Books of the Vulgate

- Ferdinand Cavallera

- Divino afflante Spiritu

- Gutenberg Bible

- Jerome

- Paula and Eustochium, Catholic saints, important collaborators of Jerome[127][128][129]

- Latin Psalters

- The Philobiblon

- Poor Man's Bible

Selected manuscripts

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Also called Biblia Vulgata ('Bible in common language'; Classical Latin: [ˈbɪ.bli.a wʊɫˈɡaː.ta], Ecclesiastical Latin: [ˈbiː.bli.a vulˈɡaː.t̪a]), sometimes referred to as the Latin Vulgate

- ^ Some, following P. Nautin (1986) and perhaps E. Burstein (1971), suggest that Jerome may have been almost wholly dependent on Greek material for his interpretation of the Hebrew. A. Kamesar (1993), on the other hand, sees evidence that in some cases Jerome's knowledge of Hebrew exceeds that of his exegetes, implying a direct understanding of the Hebrew text.

- ^ Literally "in the most correct manner possible"

References

[edit]- ^ "vetuslatina.org". vetuslatina.org. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ T. Lewis, Charlton; Short, Charles. "A Latin Dictionary | vulgo". Perseus Digital Library. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ^ Ackroyd, Peter R.; Evans, C. F.; Lampe, Geoffrey William Hugo; Greenslade, Stanley Lawrence (1980) [1970]. The Cambridge History of the Bible: Volume 1, From the Beginnings to Jerome. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09973-8.

- ^ "Vulgate | Description, Definition, Bible, History, & Facts | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 June 2024. Retrieved 10 July 2024.

- ^ a b Metzger, Bruce M. (1977). The Early Versions of the New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 348.

- ^ a b "Latin Vulgate (International Standard Bible Encyclopedia)". bible-researcher.com. 1915. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Canellis (2017), ch. "Introduction: From Jerome's...", pp. 216–7.

- ^ Plater, William Edward; Henry Julian White (1926). A grammar of the Vulgate, being an introduction to the study of the latinity of the Vulgate Bible. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e Canellis (2017), pp. 89–90, 217.

- ^ a b c Houghton, H. A. G. (2016). The Latin New Testament; a Guide to its Early History, Texts and Manuscripts. Oxford University Press. p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e Scherbenske, Eric W. (2013). Canonizing Paul: Ancient Editorial Practice and the Corpus Paulinum. Oxford University Press. p. 183.

- ^ a b Houghton, H. A. G. (2016). The Latin New Testament; a Guide to its Early History, Texts and Manuscripts. Oxford University Press. pp. 36, 41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Canellis (2017), ch. "Introduction: Revision...", p. 217.

- ^ a b c d e Bogaert, Pierre-Maurice (2005). "Le livre de Baruch dans les manuscrits de la Bible latine. Disparition et réintégration". Revue Bénédictine. 115 (2): 286–342. doi:10.1484/J.RB.5.100598.

- ^ a b Canellis (2017), ch. "Introduction: From Jerome's...", pp. 213, 217.

- ^ Chapman, John (1922). "St Jerome and the Vulgate New Testament (I–II)". The Journal of Theological Studies. o.s. 24 (93): 33–51. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXIV.93.33. ISSN 0022-5185. Chapman, John (1923). "St Jerome and the Vulgate New Testament (III)". The Journal of Theological Studies. o.s. 24 (95): 282–299. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXIV.95.282. ISSN 0022-5185.

- ^ Canellis (2017), pp. 132–133, 217.

- ^ a b "Jerome's Prologue to Daniel – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ Canellis (2017), ch. "Introduction: Revision...", pp. 133–134.

- ^ York, Harry Clinton (1910). "The Latin Versions of First Esdras". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 26 (4): 253–302. doi:10.1086/369651. JSTOR 527826. S2CID 170979647.

- ^ Canellis (2017), ch. "Introduction: Revision...", p. 98.

- ^ Weber, Robert; Gryson, Roger, eds. (2007). "Praefatio". Biblia sacra : iuxta Vulgatam versionem. Oliver Wendell Holmes Library Phillips Academy (5 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. pp. VI, XV, XXV, XXXIV. ISBN 978-3-438-05303-9.

- ^ Browning, W. R. F. (8 October 2009). A Dictionary of the Bible (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 373. ISBN 978-0-19-158506-7. Archived from the original on 3 May 2025. Retrieved 13 January 2025.

The translation of the Bible from the original languages into Latin by Jerome (from 383 to 405 CE) undertaken at the request of Pope Damasus to bring order into the various existing versions.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Goins, Scott (2014). "Jerome's Psalters". In Brown, William P. (ed.). Oxford Handbook to the Psalms. Oxford University Press. p. 188.

- ^ Scherbenske, Eric W. (2013). Canonizing Paul: Ancient Editorial Practice and the Corpus Paulinum. Oxford University Press. p. 182.

- ^ Houghton, H. A. G. (2016). The Latin New Testament; a Guide to its Early History, Texts and Manuscripts. Oxford University Press. p. 31.

- ^ Houghton, H. A. G. (2016). The Latin New Testament; a Guide to its Early History, Texts and Manuscripts. Oxford University Press. p. 36.

- ^ Scherbenske, Eric W. (2013). Canonizing Paul: Ancient Editorial Practice and the Corpus Paulinum. Oxford University Press. p. 184.

- ^ Bogaert, Pierre-Maurice (2000). "Les livres d'Esdras et leur numérotation dans l'histoire du canon de la Bible latin". Revue Bénédictine. 1o5 (1–2): 5–26. doi:10.1484/J.RB.5.100750.

- ^ Worth, Roland H. Jr. Bible Translations: A History Through Source Documents. pp. 29–30.

- ^ Pierre Nautin, article "Hieronymus", in: Theologische Realenzyklopädie, Vol. 15, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin – New York 1986, pp. 304–315, [309–310].

- ^ Adam Kamesar. Jerome, Greek Scholarship, and the Hebrew Bible: A Study of the Quaestiones Hebraicae in Genesim. Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1993. ISBN 978-0198147275. p. 97. This work cites E. Burstein, La compétence en hébreu de saint Jérôme (Diss.), Poitiers 1971.

- ^ City of God edited and abridged by Vernon J. Bourke 1958

- ^ "CHURCH FATHERS: Letter 71 (Augustine) or 104 (Jerome)". newadvent.org.

- ^ "Church Fathers: Letter 172 (Augustine) or 134 (Jerome)". newadvent.org. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Lexicon - Per cola et commata". hmmlschool.org.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to Genesis – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to Joshua – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Jerome's "Helmeted Introduction" to Kings – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to Chronicles – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Jerome's Prologue to Ezra – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to Tobias – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to Judith – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to Esther – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to Job – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to Psalms (LXX) – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to the Books of Solomon – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to Isaiah – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to Jeremiah – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to Ezekiel – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to the Twelve Prophets – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to the Gospels – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Vulgate Prologue to Paul's Letters – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Notes to the Additions to Esther – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Jerome's Prologue to Psalms (Hebrew) – biblicalia". bombaxo.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ Canellis (2017), ch. "Introduction: Revision...", pp. 99–109.

- ^ Origin of the New Testament - APPENDIX I (to § 2 of Part I, pp. 59 f.) The Marcionite Prologues to the Pauline Epistles, Adolf von Harnack, 1914. Moreover, Harnack noted: "We have indeed long known that Marcionite readings found their way into the ecclesiastical text of the Pauline epistles, but now for seven years we have known that Churches actually accepted the Marcionite prefaces to the Pauline epistles! De Bruyne has made one of the finest discoveries of later days in proving that those prefaces, which we read first in Codex Fuldensis and then in numbers of later manuscripts, are Marcionite, and that the Churches had not noticed the cloven hoof."

- ^ Houghton, H.A.G. (1 February 2016). "The Tenth Century Onwards: Scholarship and Heresy". The Latin New Testament. pp. 96–110. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198744733.003.0005.

- ^ Buron, Philip (2014). The text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research; 2nd edn. Brill Publishers. p. 182.

- ^ Houghton, H. A. G. (2016). The Latin New Testament; a Guide to its Early History, Texts and Manuscripts. Oxford University Press. p. 33.

- ^ Houghton, H. A. G. (2016). The Latin New Testament; a Guide to its Early History, Texts and Manuscripts. Oxford University Press. pp. 32, 34, 195.

- ^ Benckhuysen, Amanda W. (29 October 2019). The Gospel According to Eve: A History of Women's Interpretation. IVP Academic. p. 17. ISBN 9780830852277.

- ^ Goins, Scott (2014). "Jerome's Psalters". In Brown, William. P. (ed.). Oxford Handbook of the Psalms. OUP. p. 190.

- ^ Norris, Oliver (2017). "Tracing Fortunatianus's Psalter". In Dorfbauer, Lukas J. (ed.). Fortunatianus ridivivus. CSEL. p. 285.

- ^ Biblia Sacra iuxta vulgatam versionem. Robert Weber, Roger Gryson (eds.) (5 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. 2007. p. XXXIII.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Bogaert, Pierre-Maurice (2000). "Les livres d'Esdras et leur numérotation dans l'histoire du canon de la Bible latin". Revue Bénédictine. 110 (1–2): 5–26. doi:10.1484/J.RB.5.100750.

- ^ Sutcliffe, Edmund F. (1948). "The Council of Trent on the authentia of the Vulgate". The Journal of Theological Studies. o.s. 49 (193–194): 35–42. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XLIX.193-194.35. ISSN 0022-5185.

- ^ a b c Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent, The Fourth Session, 1546

- ^ Akin, Jimmy (5 September 2017). "Is the Vulgate the Catholic Church's Official Bible?". National Catholic Register. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ Fourth Session, April 8 1546.

- ^ "Denzinger – English translation, older numbering". patristica.net. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

2198 [...] "This decree [of January 13, 1897] was passed to check the audacity of private teachers who attributed to themselves the right either of rejecting entirely the authenticity of the Johannine comma, or at least of calling it into question by their own final judgment. But it was not meant at all to prevent Catholic writers from investigating the subject more fully and, after weighing the arguments accurately on both sides, with that and temperance which the gravity of the subject requires, from inclining toward an opinion in opposition to its authenticity, provided they professed that they were ready to abide by the judgment of the Church, to which the duty was delegated by Jesus Christ not only of interpreting Holy Scripture but also of guarding it faithfully."

- ^ a b "Divino Afflante Spiritu, Pope Pius XII, #21 (in English version)". w2.vatican.va. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ McNamara, Martin; Martin, Michael (2022). The Bible in the Early Irish Church, A.D. 550 to 850. doi:10.1163/9789004512139_011.

- ^ Tamoto, Kenichi (2019). The Macregol Gospels or The Rushworth Gospels (Introductory Part). doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.14468.27527.

- ^ a b "Cataloging Biblical Materials". Princeton Library. Princeton University Library's Cataloging Documentation. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ Skeen, William (1872). Early Typography. Colombo, Ceylon.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b E. C. Bigmore, C. W. H. Wyman (2014). A Bibliography of Printing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 288. ISBN 9781108074322.

- ^ Watt, Robert (1824). Bibliotheca Britannica; or a General Index to British and Foreign Literature. Edinburgh and London: Longman, Hurst & Co. p. 452.

- ^ Daniell, David (2003). The Bible in English: its history and influence. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 510. ISBN 0-300-09930-4.

- ^ (Daniell 2003, p. 478)

- ^ Brown, Michelle P. The Lindisfarne Gospels: Society, Spirituality and the Scribe. Vol. 1.

- ^ Smith, James E. Introduction to Biblical Studies. p. 38.

- ^ Mt 16:22

- ^ a b Kenyon, Frederic G. (1939). Our Bible and the Ancient Manuscripts (4th ed.). London. p. 83. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Linde, Cornelia (2011). "II.2 Medieval Editions". How to correct the Sacra scriptura? Textual criticism of the Latin Bible between the twelfth and fifteenth century. Medium Ævum Monographs 29. Oxford: Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature. p. 39. ISBN 978-0907570226.

- ^ Linde, Cornelia (2011). "II.2 Medieval Editions". How to correct the Sacra scriptura? Textual criticism of the Latin Bible between the twelfth and fifteenth century. Medium Ævum Monographs 29. Oxford: Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature. pp. 39–41. ISBN 978-0907570226.

- ^ Linde, Cornelia (2011). "II.2 Medieval Editions". How to correct the Sacra scriptura? Textual criticism of the Latin Bible between the twelfth and fifteenth century. Medium Ævum Monographs 29. Oxford: Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature. pp. 41–2. ISBN 978-0907570226.

- ^ Linde, Cornelia (2011). "II.2 Medieval Editions". How to correct the Sacra scriptura? Textual criticism of the Latin Bible between the twelfth and fifteenth century. Medium Ævum Monographs 29. Oxford: Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature. pp. 39, 250. ISBN 978-0907570226.

- ^ Linde, Cornelia (2011). "II.2 Medieval Editions". How to correct the Sacra scriptura? Textual criticism of the Latin Bible between the twelfth and fifteenth century. Medium Ævum Monographs 29. Oxford: Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature. p. 47. ISBN 978-0907570226.

- ^ Linde, Cornelia (2011). "II.2 Medieval Editions". How to correct the Sacra scriptura? Textual criticism of the Latin Bible between the twelfth and fifteenth century. Medium Ævum Monographs 29. Oxford: Society for the Study of Medieval Languages and Literature. pp. 42–47. ISBN 978-0907570226.

- ^ Berger, Samuel (1879). La Bible au seizième siècle: Étude sur les origines de la critique biblique (in French). Paris. p. 147 ff. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose (1894). "Chapter III. Latin versions". In Miller, Edward (ed.). A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament. Vol. 2 (4th ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. p. 64.

- ^ a b "Vulgate in the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia". International Standard Bible Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ^ Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan (1996). "Catalog of Exhibition [Item 1.14]". The reformation of the Bible, the Bible of the Reformation. Dallas : Bridwell Library; Internet Archive. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 98. ISBN 9780300066678.

- ^ Metzger, Bruce M. (1977). The Early Versions of the New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 348–349.

- ^ Scrivener, Frederick Henry Ambrose; Edward Miller (1894). A Plain Introduction to the Criticism of the New Testament. Vol. 2 (4 ed.). London: George Bell & Sons. p. 64.

- ^ a b Hastings, James (2004) [1898]. "Vulgate". A Dictionary of the Bible. Vol. 4, part 2 (Shimrath – Zuzim). Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific. p. 881. ISBN 978-1410217295.

- ^ a b Metzger, Bruce M. (1977). The Early Versions of the New Testament. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 349.

- ^ a b Pelikan, Jaroslav Jan (1996). "1 : Sacred Philology; Catalog of Exhibition [Item 1.14]". The reformation of the Bible, the Bible of the Reformation. Dallas : Bridwell Library; Internet Archive. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 14, 98. ISBN 9780300066678.

- ^ Weber, Robert; Gryson, Roger, eds. (2007). "Praefatio". Biblia sacra : iuxta Vulgatam versionem. Oliver Wendell Holmes Library, Phillips Academy (5th ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. pp. IX, XVIII, XXVIII, XXXVII. ISBN 978-3-438-05303-9.

- ^ Gasquet, F.A. (1912). Revision of Vulgate. In the Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ Lachmann, Karl (1842–50). Novum Testamentum graece et latine. Berlin: Reimer. (Google Books: Volume 1, Volume 2)

- ^ "Novum Testamentum Vulgatae editionis juxta textum Clementis VIII.: Romanum ex Typogr. Apost. Vatic. A.1592. accurate expressum. Cum variantibus in margine lectionibus antiquissimi et praestantissimi codicis olim monasterii Montis Amiatae in Etruria, nunc bibliothecae Florentinae Laurentianae Mediceae saec. VI. p. Chr. scripti. Praemissa est commentatio de codice Amiatino et versione latina vulgata". Sumtibus et Typis C. Tauchnitii. 26 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Nestle, Eberhard (1906). Novum Testamentum Latine: textum Vaticanum cum apparatu critico ex editionibus et libris manu scriptis collecto imprimendum. Stuttgart: Württembergische Bibelanstalt.

- ^ Kilpatrick, G. D. (1978). "The Itala". The Classical Review. n.s. 28 (1): 56–58. doi:10.1017/s0009840x00225523. JSTOR 3062542. S2CID 163698896.

- ^ Wordsworth, John (1883). The Oxford critical edition of the Vulgate New Testament. Oxford. p. 4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Watson, E.W. (1915). Life of Bishop John Wordsworth. London: Longmans, Green.

- ^ Nouum Testamentum Domini nostri Iesu Christi Latine, secundum editionem sancti Hieronymi. John Wordsworth, Henry Julian White (eds.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1889–1954.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) 3 vols. - ^ Biblia Sacra iuxta vulgatam versionem. Robert Weber, Roger Gryson (eds.) (5 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. 2007. p. XLVI.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Houghton, H. A. G. (2016). The Latin New Testament; a Guide to its Early History, Texts and Manuscripts. Oxford University Press. p. 130.

- ^ H. A. G. Houghton (2016). The Latin New Testament: A Guide to Its Early History, Texts, and Manuscripts. Oxford University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0198744733. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ Biblia Sacra iuxta latinam vulgatam versionem. Pontifical Abbey of St Jerome-in-the-City (ed.). Rome: Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 1995 [1926]. ISBN 8820921286.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) 18 vols. - ^ Gasquet, F.A. (1912). "Vulgate, Revision of". The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Burkitt, F.C. (1923). "The text of the Vulgate". The Journal of Theological Studies. o.s. 24 (96): 406–414. doi:10.1093/jts/os-XXIV.96.406. ISSN 0022-5185.

- ^ Kraft, Robert A. (1965). "Review of Biblia Sacra iuxta Latinam vulgatam versionem ad codicum fidem iussu Pauli Pp. VI. cura et studio monachorum abbatiae pontificiae Sancti Hieronymi in Urbe ordinis Sancti Benedicti edita. 12: Sapientia Salomonis. Liber Hiesu Filii Sirach". Gnomon. 37 (8): 777–781. ISSN 0017-1417. JSTOR 27683795. Préaux, Jean G. (1954). "Review of Biblia Sacra iuxta latinum vulgatam versionem. Liber psalmorum ex recensione sancti Hieronymi cum praefationibus et epistula ad Sunniam et Fretelam". Latomus. 13 (1): 70–71. JSTOR 41520237.

- ^ Weld-Blundell, Adrian (1947). "The Revision of the Vulgate Bible" (PDF). Scripture. 2 (4): 100–104.

- ^ Biblia Sacra iuxta vulgatam versionem. Robert Weber, Roger Gryson (eds.) (5 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. 2007. p. XLIII.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Scripturarum Thesarurus, Apostolic Constitution, 25 April 1979, John Paul II". Vatican: The Holy See. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Pope John Paul II. "Epistula Vincentio Truijen OSB Abbati Claravallensi, 'De Pontificia Commissione Vulgatae editioni recognoscendae atque emendandae'". Vatican: The Holy See. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ "Bibliorum Sacrorum Vetus Vulgata". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Biblia Sacra iuxta vulgatam versionem. Robert Weber, Roger Gryson (eds.) (5 ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. 2007. ISBN 978-3-438-05303-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Die Vulgata (ed. Weber/Gryson)". bibelwissenschaft.de. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ Stramare, Tarcisio (1981). "Die Neo-Vulgata. Zur Gestaltung des Textes". Biblische Zeitschrift. 25 (1): 67–81. doi:10.30965/25890468-02501005. S2CID 244689083.

- ^ "Scripturarum Thesarurus, Apostolic Constitution, 25 April 1979, John Paul II". Vatican: The Holy See. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ Marshall, Taylor (23 March 2012). "Which Latin Vulgate Should You Purchase?". Taylor Marshall. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Houghton, H. A. G. (2016). The Latin New Testament: A Guide to Its Early History, Texts, and Manuscripts. Oxford University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0198744733.

- ^ Woman's Work in Bible Study and Translation, Zahm, John Augustine ("A.H. Johns") (1912), in The Catholic World, New York, Vol. 95/June 1912 (bibliographic details see here and here), via CatholicCulture.org. Retrieved 4 Sept 2021.

- ^ "St. Paula, Roman Matron". Vatican News. Retrieved 6 September 2021.

- ^ Hardesty, Nancy (1988). "Paula: A Portrait of 4th Century Piety". Christian History (17, "Women In The Early Church"). Worcester, PA: Christian History Institute. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Canellis, Aline, ed. (2017). Jérôme : Préfaces aux livres de la Bible [Jerome : Preface to the books of the Bible] (in French). Abbeville: Éditions du Cerf. ISBN 978-2-204-12618-2.

- Chapter "Introduction : Révision et retourn à l'Hebraica veritas" ('Introduction: Revision and return to Hebraica veritas ')

- Chapter "Introduction : Du travail de Jérôme à la Vulgate ('Introduction: From Jerome's work to the Vulgate')

Further reading

[edit]- Berger, Samuel (1893). Histoire de la Vulgate pendant les premiers siècles du Moyen Age. Paris: Librarie Hachette et C.

- Draguet, R. (1946). "Le Maître louvainiste, [Jean] Driedo, inspirateur du décret de Trente sur la Vulgate". Festschrift volume, Miscellenea historica in honorem Alberti de Meyer. Louvain: Bibliothèque universitaire. pp. 836–854.

- Gameson, Richard, ed. (1994). The Early Medieval Bible. Cambridge University Press.

- Houghton, H. A. G., ed. (2023). The Oxford Handbook of the Latin Bible. Oxford University Press.

- Lampe, G. W. M., ed. (1969). The Cambridge History of the Bible. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press.

- Lang, Bernhard (2023). Handbook of the Vulgate Bible and its reception. Vulgata in Dialogue. ISSN 2504-5156.

- Marsden, Richard (1995). The Text of the Old Testament in Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge University Press.

- Schmid Pfändler, Brigitta; Fieger, Michael (2023). Nicht am Ende mit dem Latein. Die Vulgata aus heutiger Sicht. Lausanne/Berlin: Lang, ISBN 978-3-0343-4744-0 (Open Access).

- Turner, C. H. (1931). The Oldest Manuscript of the Vulgate Gospels. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

- Van Liere, Frans (2014). Introduction to the Medieval Bible. Cambridge University Press.

- Steinmeuller, John E. (1938). "The History of the Latin Vulgate". CatholicCulture. Homiletic & Pastoral Review. pp. 252–257. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Gallagher, Edmon (2015). "Why Did Jerome Translate Tobit and Judith?". Harvard Theological Review. 108 (3): 356–75. doi:10.1017/S0017816015000231. S2CID 164400348 – via Academia.edu.

External links

[edit]Clementine Vulgate

- The Clementine Vulgate, fully searchable and possible to compare with both the Douay Rheims and Knox Bibles side by side.

- Clementine Vulgate 1822, including Apocrypha

- Clementine Vulgate 1861, including Apocrypha

- The Clementine Vulgate, searchable Archived 24 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Michael Tweedale, et alii. Other installable modules include Weber's Stuttgart Vulgate. Missing 3 and 4 Esdras, and Manasses.

- Vulgata, Hieronymiana versio (Jerome's version), Latin text complete as ebook (public domain)

- The Vulgate New Testament, with the Douay Version of 1582. In Parallel Columns (London 1872).

Oxford Vulgate

- Wordsworth, John; White, Henry Julian, eds. (1889). Nouum Testamentum Domini nostri Jesu Christi latine, secundum editionem Sancti Hieronymi. Vol. 1. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

- Wordsworth, John; White, Henry Julian, eds. (1941). Nouum Testamentum Domini nostri Jesu Christi latine, secundum editionem Sancti Hieronymi. Vol. 2. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

- Wordsworth, John; White, Henry Julian, eds. (1954). Nouum Testamentum Domini nostri Jesu Christi latine, secundum editionem Sancti Hieronymi. Vol. 3. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

Stuttgart Vulgate

- Weber-Gryson (Stuttgart) edition, official online text

- Latin Vulgate with Parallel English Douay-Rheims and King James Version, Stuttgart edition, but missing 3 and 4 Esdras, Manasses, Psalm 151, and Laodiceans.

Nova Vulgata

- Nova Vulgata, from the Vatican website

Miscellaneous translations

- Jerome's Biblical Prefaces

- Vulgate text of Laodiceans including a parallel English translation

Works about the Vulgate

.jpg/250px-Cod._Sangallensis_63_(277).jpg)

.jpg/1650px-Cod._Sangallensis_63_(277).jpg)