Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Moloch

View on Wikipedia

Moloch,[a] Molech, or Molek[b] is a word which appears in the Hebrew Bible several times, primarily in the Book of Leviticus. The Greek Septuagint translates many of these instances as "their king", but maintains the word or name Moloch in others, including one additional time in the Book of Amos where the Hebrew text does not attest the name. The Bible strongly condemns practices that are associated with Moloch, which are heavily implied to include child sacrifice.[2]

Traditionally, the name Moloch has been understood as referring to a Canaanite god.[3] However, since 1935, scholars have speculated that Moloch refers to the sacrifice itself, since the Hebrew word mlk is identical in spelling to a term that means "sacrifice" in the closely related Punic language.[4] This second position has grown increasingly popular, but it remains contested.[5] Among proponents of this second position, controversy continues as to whether the sacrifices were offered to Yahweh or another deity, and whether they were a native Israelite religious custom or a Phoenician import.[6]

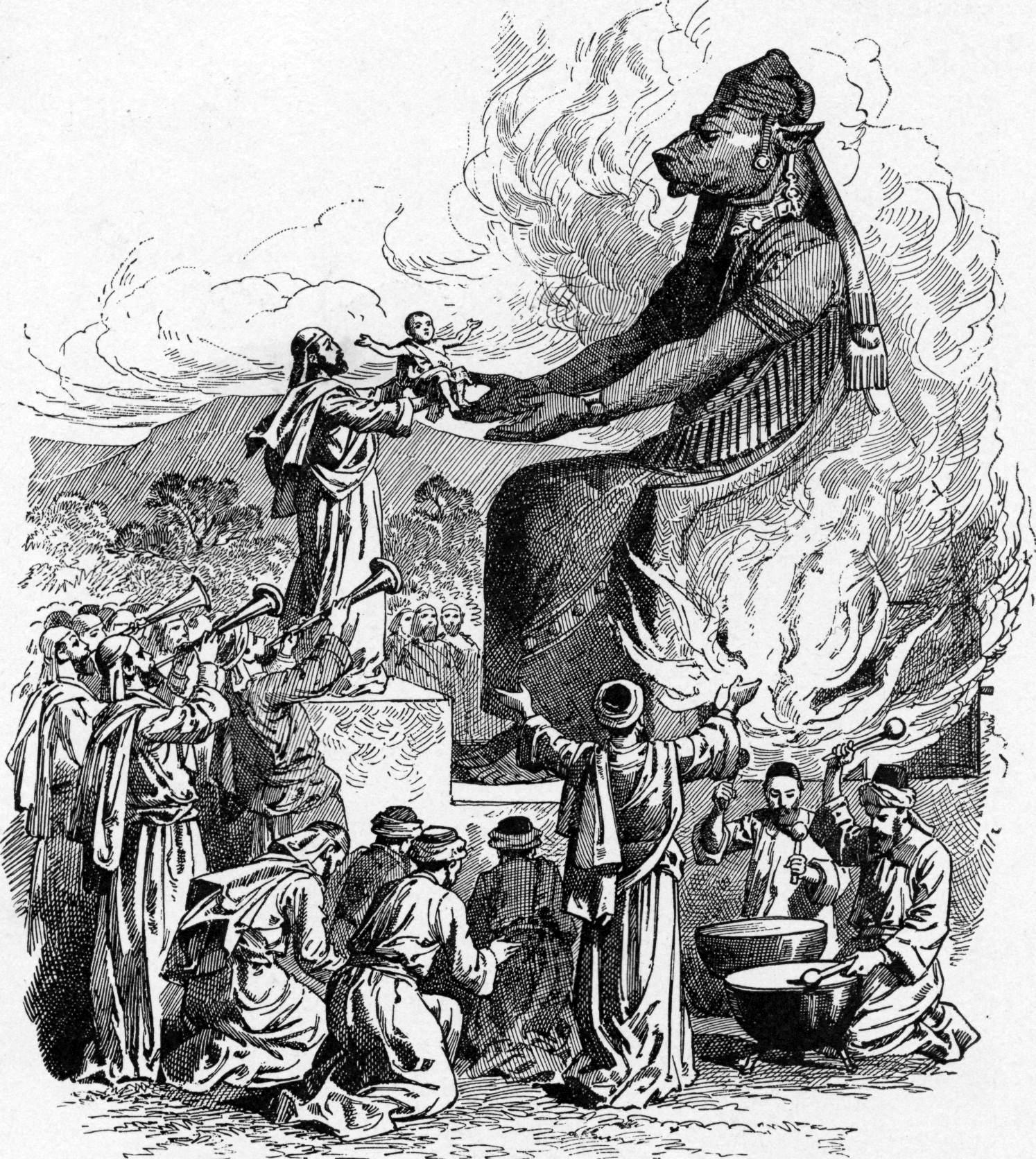

Since the medieval period, Moloch has often been portrayed as a bull-headed idol with outstretched hands over a fire; this depiction takes the brief mentions of Moloch in the Bible and combines them with various sources, including ancient accounts of Carthaginian child sacrifice and the legend of the Minotaur.[7]

Beginning in the modern era, "Moloch" has been figuratively used in reference to a power which demands a dire sacrifice.[8] A god Moloch appears in various works of literature and film, such as John Milton's Paradise Lost (1667), Gustave Flaubert's Salammbô (1862), Giovanni Pastrone's Cabiria (1914), Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927), and Allen Ginsberg's "Howl" (1955).

Etymology

[edit]

The etymology of Moloch is uncertain: a derivation from the root mlk, which means "to rule" is "widely recognized".[10] Since it was first proposed by Abraham Geiger in 1857, some scholars have argued that the word "Moloch" has been altered by using the vowels of bōšet "shame".[11] Other scholars have argued that the name is a qal participle from the same verb.[12] R. M. Kerr criticizes both theories by noting that the name of no other god appears to have been formed from a qal participle, and that Geiger's proposal is "an out-of-date theory which has never received any factual support".[13] Paul Mosca, Professor Emeritus at the University of British Columbia, similarly argued that "the theory that a form molek would immediately suggest to the reader or hearer the word boset (rather than qodes or ohel) is the product of nineteenth century ingenuity, not of Massoretic [sic] or pre-Massoretic tendentiousness".[14]

Scholars who do not believe that Moloch represents a deity instead compare the name to inscriptions in the closely related Punic language where the word mlk (molk or mulk) refers to a type of sacrifice, a connection first proposed by Otto Eissfeldt (1935).[15] Eissfeldt himself, following Jean-Baptiste Chabot, connected Punic mlk and Moloch to a Syriac verb mlk meaning "to promise", a theory also supported as "the least problematic solution" by Heath Dewrell (2017).[16] Eissfeldt's proposed meaning included both the act and the object of sacrifice.[4] Scholars such as W. von Soden argue that the term is a nominalized causative form of the verb ylk/wlk, meaning "to offer", "present", and thus means "the act of presenting" or "thing presented".[17] Kerr instead derives both the Punic and Hebrew word from the verb mlk, which he proposes meant "to own", "to possess" in Proto-Semitic, only later coming to mean "to rule"; the meaning of Moloch would thus originally have been "present", "gift", and later come to mean "sacrifice".[18]

The spelling "Moloch" follows the Greek Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate; the spelling "Molech" or "Molek" follows the Tiberian vocalization of Hebrew, with "Molech" used in the English King James Bible.[19]

Biblical attestations

[edit]Masoretic Text

[edit]The word Moloch (מלך) occurs eight times in the Masoretic Text, the standard Hebrew text of the Bible. Five of these are in Leviticus, with one in 1 Kings, one in 2 Kings and another in The Book of Jeremiah. Seven instances include the Hebrew definite article ha- ('the') or have a prepositional form indicating the presence of the definite article.[10] All of these texts condemn Israelites who engage in practices associated with Moloch, and most associate Moloch with the use of children as offerings.[20]

Leviticus repeatedly forbids the practice of offering children to Moloch:

And thou shalt not give any of thy seed to set them apart to Molech, neither shalt thou profane the name of thy God: I am the LORD.

The majority of the Leviticus references come from a single passage of four lines:[21]

Moreover, thou shalt say to the children of Israel: Whosoever he be of the children of Israel, or of the strangers that sojourn in Israel, that giveth of his seed unto Molech; he shall surely be put to death; the people of the land shall stone him with stones. I also will set My face against that man, and will cut him off from among his people, because he hath given of his seed unto Molech, to defile My sanctuary, and to profane My holy name. And if the people of the land do at all hide their eyes from that man, when he giveth of his seed unto Molech, and put him not to death; then I will set My face against that man, and against his family, and will cut him off, and all that go astray after him, to go astray after Molech, from among their people.

In 1 Kings, Solomon is portrayed as introducing the cult of Moloch to Jerusalem:

Then did Solomon build a high place for Chemosh the detestation of Moab, in the mount that is before Jerusalem, and for Molech the detestation of the children of Ammon.

This is the sole instance of the name Moloch occurring without the definite article in the Masoretic text: it may offer a historical origin of the Moloch cult in the Bible,[10] or it may be a mistake for Milcom, the Ammonite god (thus the reading in some manuscripts of the Septuagint).[12][10]

In 2 Kings, Moloch is associated with the tophet in the valley of Gehenna when it is destroyed by king Josiah:

And he defiled Topheth, which is in the valley of the son of Hinnom, that no man might make his son or his daughter to pass through the fire to Molech.

The same activity of causing children "to pass over the fire" is mentioned, without reference to Moloch, in numerous other verses of the Bible, such as in Deuteronomy (Deuteronomy 12:31, 18:10), 2 Kings (2 Kings 16:3; 17:17; 17:31; 21:6), 2 Chronicles (2 Chronicles 28:3; 33:6), the Book of Jeremiah (Jeremiah 7:31, 19:5) and the Book of Ezekiel (Ezekiel 16:21; 20:26, 31; 23:37).[22]

Lastly, the prophet Jeremiah condemns practices associated with Moloch as showing infidelity to Yahweh:[23]

And they built the high places of Baal, which are in the valley of the son of Hinnom, to set apart their sons and their daughters unto Molech; which I commanded them not, neither came it into My mind, that they should do this abomination; to cause Judah to sin.

Given the name's similarity to the Hebrew word melek "king", scholars have also searched the Masoretic text to find instances of melek that may be mistakes for Moloch. Most scholars consider only one instance as likely a mistake, in Isaiah:[24]

For a hearth is ordered of old; yea, for the king [melek] it is prepared, deep and large; the pile thereof is fire and much wood; the breath of the LORD, like a stream of brimstone, doth kindle it.

Septuagint and New Testament

[edit]The standard text of the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Old Testament, contains the name "Moloch" (Μολόχ) at 2 Kings 23:10 and Jeremiah 30:35, as in the Masoretic text, but without an article.[10] Moreover, the Septuagint uses the name Moloch in Amos where it is not found in the Masoretic text:

You even took up the tent of Moloch and the star of your god Raiphan, models of them which you made for yourselves.

Additionally, some Greek manuscripts of Zephaniah 1:5 contain the name "Moloch" or "Milcom" rather than the Masoretic text's "their king," the reading also found in the standard Septuagint. Many English translations follow one or the other of these variants, reading either "Moloch" or "Milcom".[26] However, instead of "Moloch", the Septuagint translates the instances of Moloch in Leviticus as "ruler" (ἄρχων), and as "king" (βασιλεύς) at 1 Kings 11:7.[12][c]

The Greek version of Amos with Moloch is quoted in the New Testament and accounts for the one occurrence of Moloch there (Acts 7:43).[12]

Theories

[edit]As a deity

[edit]

Before 1935, all scholars held that Moloch was a pagan deity,[3] to whom child sacrifice was offered at the Jerusalem tophet.[4] Some modern scholars have proposed that Moloch may be the same god as Milcom, Adad-Milki, or an epithet for Baal.[27]

G. C. Heider and John Day connect Moloch with a deity Mlk attested at Ugarit and Malik attested in Mesopotamia and proposes that he was a god of the underworld, as in Mesopotamia Malik is twice equated with the underworld god Nergal. Day also notes that Isaiah seems to associate Moloch with Sheol.[28] The Ugaritic deity Mlk also appears to be associated with the underworld,[21] and the similarly named Phoenician god Melqart (literally "king of the city") could have underworld associations if "city" is understood to mean "underworld", as proposed by William F. Albright.[21] Heider also argued that there was also an Akkadian term maliku referring to the shades of the dead.[17][29]

The notion that Moloch is the name of a deity has been challenged for several reasons. Moloch is rarely mentioned in the Bible, is not mentioned at all outside of it, and connections to other deities with similar names are uncertain.[4] Moreover, it is possible that some of the supposed deities named Mlk are epithets for another god, given that mlk can also mean "king".[30] The Israelite rite conforms, on the other hand, to the Punic mlk rite in that both involved the sacrifice of children.[31] None of the proposed gods Moloch could be identified with are associated with human sacrifice, the god Mlk of Ugarit appears to have only received animal sacrifice, and the mlk sacrifice is never offered to a god named Mlk but rather to another deity.[17]

Brian Schmidt argues that the use of Moloch without an article at 1 Kings 11:7 and the use of Moloch as a proper name without an article in the Septuagint may indicate that there was a tradition of a god Moloch when the Bible was originally composed. However, this god may have only existed in the imagination of the composers of the Bible rather than in historical reality.[10]

As a form of sacrifice

[edit]

In 1935, Otto Eissfeldt proposed, on the basis of Punic inscriptions, that Moloch was a form of sacrifice rather than a deity.[4] Punic inscriptions commonly associate the word mlk with three other words: ʾmr (lamb), bʿl (citizen) and ʾdm (human being). bʿl and ʾdm never occur in the same description and appear to be interchangeable.[32] Other words that sometimes occur are bšr (flesh).[17] When put together with mlk, these words indicate a "mlk-sacrifice consisting of...".[32] The Biblical term lammolekh would thus be translated not as "to Moloch", as normally translated, but as "as a molk-sacrifice", a meaning consistent with uses of the Hebrew preposition la elsewhere.[33] Bennie Reynolds further argues that Jeremiah's use of Moloch in conjunction with Baal in Jer 32:35 is parallel to his use of "burnt offering" and Baal in Jeremiah 19:4–5.[34]

The view that Moloch refers to a type of sacrifice was challenged by John Day and George Heider in the 1980s.[35] Day and Heider argued that it was unlikely that biblical commentators had misunderstood an earlier term for a sacrifice as a deity and that Leviticus 20:5's mention of "whoring after Moloch" necessarily implied that Moloch was a god.[36][37] Day and Heider nevertheless accepted that mlk was a sacrificial term in Punic, but argue that it did not originate in Phoenicia and that it was not brought back to Phoenicia by the Punic diaspora. More recently, Anthony Frendo argues that the Hebrew equivalent to Punic ylk (the root of Punic mlk) is the verb ‘br "to pass over"; in Frendo's view, this means that the Hebrew Moloch is not derived from the same root as Punic mlk.[38]

Since Day's and Heider's objections, a growing number of scholars have come to believe that Moloch refers to the mulk sacrifice rather than a deity.[5] Francesca Stavrakopoulou argues that "because both Heider and Day accept Eissfeldt's interpretation of Phoenician-Punic mlk as a sacrificial term, their positions are at once compromised by the possibility that biblical mōlekh could well function in a similar way as a technical term for a type of sacrifice".[39] She further argues that "whoring after Moloch" does not need to imply a deity as mlk refers to both the act of sacrificing and the thing sacrificed, allowing an interpretation of "whor[ing] after the mlk-offering".[39] Heath Dewrell argues that the translation of Leviticus 20:5 in the Septuagint, which substitutes Greek: ἄρχοντας "archons, princes" for Moloch, implies that the biblical urtext did not include the phrase "whoring after Moloch".[40] Bennie Reynolds further notes that at least one inscription from Tyre does appear to mention mlk sacrifice (RES 367); therefore Day and Heider are incorrect that the practice is unattested in Canaan (Phoenicia). Reynolds also argues for further parallels.[41] However, Dewrell argues that the inscription is probably a modern forgery based on the unusual layout of the text and linguistic abnormalities, among other reasons.[42]

Among scholars who believe that Moloch refers to a form of sacrifice, debate remains as to whether the Israelite mlk sacrifices were offered to Yahweh or another deity.[6] Armin Lange suggests that the Binding of Isaac represents a mlk-sacrifice to Yahweh in which the child is finally substituted with a sheep, noting that Isaac was meant to be a burnt offering.[43] This opinion is shared by Stavrakopoulou, who also points to the sacrifice of Jephthah of his daughter as a burnt offering.[22] Frendo, while he argues that Moloch refers to a god, accepts Stavrakopoulou's argument that the sacrifices in the tophet were originally to Yahweh.[44] Dewrell argues that although mlk sacrifices were offered to Yahweh, they were distinct from other forms of human or child sacrifice found in the Bible (such as that of Jephthah) and were a foreign custom imported by the Israelites from the Phoenicians during the reign of Ahaz.[45]

As a divine title

[edit]Because the name "Moloch" is almost always accompanied by the definite article in Hebrew, it is possible that it is a title meaning "the king", as it is sometimes translated in the Septuagint.[10] In the twentieth century, the philosopher Martin Buber proposed that "Moloch" referred to "Melekh Yahweh".[46] A similar view was later expressed by T. Römer (1999).[47] Brian Schmidt, however, argues that the mention of Baal in Jeremiah 32:35 suggests that "the ruler" could have instead referred to Baal.[10]

As a rite of passage

[edit]A minority of scholars,[22] mainly scholars of Punic studies,[6] has argued that the ceremonies to Moloch are in fact a non-lethal dedication ceremony rather than a sacrifice. These theories are partially supported by commentary in the Talmud and among early Jewish commentators of the Bible.[22] Rejecting such arguments, Paolo Xella and Francesca Stavrakopoulou note that the Bible explicitly connects the ritual to Moloch at the tophet with the verbs indicating slaughter, killing in sacrifice, deities "eating" the children, and holocaust.[22] Xella also refers to Carthaginian and Phoenician child sacrifice found referenced in Greco-Roman sources.[48]

Religious interpretation

[edit]In Judaism

[edit]

The oldest classical rabbinical texts, the mishnah (3rd century CE) and Talmud (200s CE) include the Leviticus prohibitions of giving one's seed to Moloch, but do not clearly describe what this might have historically entailed.[49] Early midrash regarded the prohibition to giving one's seed to Moloch at Leviticus 21:18 as no longer applicable in a literal sense. The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael explains that Moloch refers to any foreign religion, while Megillah in the Babylonian Talmud explains that Moloch refers to the gentiles.[50] Likewise, the late antique Targum Neofiti and the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, interpret the verse to mean a Jewish man having sex with a gentile.[51] The earlier Book of Jubilees (2nd century BCE) shows that this reinterpretation was known already during the Second Temple Period; Jubilees uses the story of Dinah to show that marrying one's daughter to a gentile was also forbidden (Jubilees 30:10).[52] Such non-literal interpretations are condemned in the Mishnah (Megilla 4:9).[49]

Medieval rabbis argued about whether the prohibition of giving to Moloch referred to sacrifice or something else. For instance, Menachem Meiri (1249–1315) argued that "giving one's seed unto Moloch" referred to an initiation rite and not a form of idolatry or sacrifice.[49] Other rabbis disagreed. The 8th- or 9th-century midrash Tanḥuma B, gives a detailed description of Moloch worship in which the Moloch idol has the face of a calf and offerings are placed in its outstretched hands to be burned.[49] This portrayal has no basis in the Bible or Talmud and probably derives from sources such as Diodorus Siculus on Carthaginian child sacrifice as well as various other classical portrayals of gruesome sacrifice.[53][54] The rabbis Rashi (1040–1105) and Joseph ben Isaac Bekhor Shor (12th century) may rely on Tanḥuma B when they provide their own description of Moloch sacrifices in their commentaries.[49] The medieval rabbinical tradition also associated Moloch with other similarly named deities mentioned in the Bible such as Milcom, Adrammelek, and Anammelech.[55]

In Christianity

[edit]The Church Fathers only discuss Moloch occasionally,[55] mostly in commentaries on the Book of Amos or the Acts of the Apostles (where Stephen summarizes the Old Testament before being martyred). Early Christian commentators mostly either used Moloch to show the sinfulness of the Jews or to exhort Christians to morality.[56] Discussion of Moloch is also rare during the medieval period, and was mostly limited to providing descriptions of what the commentators believed Moloch sacrifice entailed.[57] Such descriptions, as found in Nicholas of Lyra (1270–1349), derive from the rabbinical tradition.[58]

During the Reformation, on the other hand, protestant commentators such as John Calvin and Martin Luther used Moloch as a warning against falling into idolatry and to disparage Catholic practices.[57] Jehovah's Witnesses understand Moloch as a god of worship of the state, following ideas first expressed by Scottish minister Alexander Hislop (1807–1865).[59]

In art and culture

[edit]In art

[edit]

Images of Moloch did not grow popular until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when Western culture began to experience a fascination with demons.[1] These images tend to portray Moloch as a bull- or lion-headed humanoid idol, sometimes with wings, with arms outstretched over a fire, onto which the sacrificial child is placed.[7][1] This portrayal can be traced to medieval Jewish commentaries such as that by Rashi, which connected the biblical Moloch with depictions of Carthaginian sacrifice to Cronus (Baal Hammon) found in sources such as Diodorus, with George Foot Moore suggesting that the bull's head may derive from the mythological Minotaur.[60] John S. Rundin suggests that further sources for the image are the legend of Talos and the brazen bull built for king Phalaris of the Greek city of Acragas on Sicily. He notes that both legends, as well as that of the Minotaur, have potential associations with Semitic child sacrifice.[61]

In contrast, William Blake portrayed Moloch as an entirely humanoid idol with a winged demon soaring above in his "Flight of Moloch" one of his illustrations of Milton's poem On the Morning of Christ's Nativity.[1]

In literature

[edit]

Moloch appears as a child-eating fallen angel in John Milton's epic poem Paradise Lost (1667). He is described as "horrid king besmeared with blood / Of human sacrifice, and parents’ tears" (1:392–393) and leads the procession of rebel angels.[62] Later, Moloch is the first speaker at the council of hell and advocates for open war against heaven.[63] Milton's description of Moloch is one of the most influential for modern conceptions of this demon or deity.[19] Milton also mentions Moloch in his poem "On the Morning of Christ's Nativity", where he flees from his grisly altars.[62] Similar portrayals of Moloch as in Paradise Lost can be found in Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock's epic poem Messias (1748–1773),[8] and in Alfred, Lord Tennyson's poem The Dawn, where Moloch represents the barbarism of past ages.[63]

In Gustave Flaubert's Salammbô, a historical novel about Carthage published in 1862, Moloch is a Carthaginian god who embodies the male principle and the destructive power of the sun.[64] Additionally, Moloch is portrayed as the husband of the Carthaginian goddess Tanit.[65] Sacrifices to Moloch are described at length in chapter 13.[62] The sacrifices are portrayed in an orientalist and exoticized fashion, with children sacrificed in increasing numbers to burning furnaces found in the statue of the god.[66] Flaubert defended his portrayal against criticism by saying it was based on the description of Carthaginian child sacrifice found in Diodorus Siculus.[64]

From the nineteenth century onward, Moloch has often been used in literature as a metaphor for some form of social, economic or military oppression, as in Charles Dickens' novella The Haunted Man (1848), Alexander Kuprin's novel Moloch (1896), and Allen Ginsberg's long poem Howl (1956), where Moloch symbolizes American capitalism.[62]

Moloch is also often used to describe something that debases society and feeds on its children, as in Percy Bysshe Shelley's long poem Peter Bell the Third (1839), Herman Melville's poem The March into Virginia (1866) about the American Civil War, and Joseph Seamon Cotter, Jr.'s poem Moloch (1921) about the First World War.[62]

As social or political allegory

[edit]

In modern times, a metaphorical meaning of Moloch as a destructive force or system that demands sacrifice, particularly of children, has become common. Beginning with Samuel Laing's National Distress (1844), the modern city is often described as a Moloch, an idea found also in Karl Marx; additionally, war often comes to be described as Moloch.[8]

The Munich Cosmic Circle (c. 1900) used Moloch to describe a person operating under cold rationalism, something they viewed as causing the degeneration of Western civilization.[67] Conservative Christians often rhetorically equate abortion with the sacrifice of children to Moloch.[59] Bertrand Russell, on the other hand, used Moloch to describe a kind of cruel, primitive religion in A Freeman's Worship (1923); he then used it to attack religion more generally.[67]

In film and television

[edit]

The 1914 Italian film Cabiria is set in Carthage and is loosely based on Flaubert's Salammbô.[68] The film features a bronzed, full-three dimensional statue of Moloch which is today kept in National Museum of Cinema in Turin, Italy.[1] The titular female slave Cabiria is saved from the priests of Moloch just before she was to be sacrificed to the idol during the night.[69] The depiction of the sacrifices to Moloch are based on Flaubert's descriptions, while the entrance of Moloch's temple is modeled on a hellmouth. Cabiria's depiction of the temple and statue of Moloch would go on to influence other filmic depictions of Moloch, such as that in Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927), in which it is workers rather than children who are sacrificed, and Sergio Leone's The Colossus of Rhodes (1961).[70]

Moloch has continued to be used as a name for horrific figures who are depicted as connected to the demon or god but often bear little resemblance to the traditional image. This includes television appearances in Stargate SG1 as an alien villain, in Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Supernatural, and Sleepy Hollow.[1]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ /ˈmɒlək, ˈmoʊlɒk/. See "Moloch". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2025-08-06.

- ^ Biblical Hebrew: מֹלֶךְ Mōleḵ, properly הַמֹּלֶךְ, hamMōleḵ "the Moloch"; Ancient Greek: Μόλοχ; Latin: Moloch

- ^ The Lucian recension of the Septuagint contains the name "Milcom" at 1 Kings 11:7.[10]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g Soltes 2021.

- ^ Stavrakopoulou 2013, pp. 134–144.

- ^ a b Day 2000, p. 209.

- ^ a b c d e Stavrakopoulou 2013, p. 144.

- ^ a b Stavrakopoulou 2013, p. 147.

- ^ a b c Xella 2013, p. 265.

- ^ a b Rundin 2004, pp. 429–439.

- ^ a b c Boysen & Ruwe 2021.

- ^ Day 2000, p. 212.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schmidt 2021.

- ^ Day 2000, p. 128.

- ^ a b c d Heider 1999, p. 581.

- ^ Kerr 2018, p. 67.

- ^ Mosca 1975, p. 127.

- ^ Heider 1999, pp. 581–582.

- ^ Dewrell 2017, pp. 127–128.

- ^ a b c d Holm 2005, p. 7134.

- ^ Kerr 2018.

- ^ a b Dewrell 2017, p. 4.

- ^ Stavrakopoulou 2013, pp. 143–144.

- ^ a b c Heider 1999, p. 583.

- ^ a b c d e Stavrakopoulou 2013, p. 140.

- ^ Stavrakopoulou 2013, p. 143.

- ^ Heider 1999, p. 585.

- ^ Pietersma & Wright 2014, p. 793.

- ^ Werse 2018, p. 505.

- ^ Day 2000, p. 213.

- ^ Day 2000, pp. 213–215.

- ^ Dewrell 2017, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Stavrakopoulou 2013, p. 146.

- ^ Dewrell 2017, p. 35.

- ^ a b Xella 2013, p. 269.

- ^ Reynolds 2007, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Reynolds 2007, pp. 445–446.

- ^ Stavrakopoulou 2013, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Day 2000, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Heider 1999, pp. 582–583.

- ^ Frendo 2016, p. 349.

- ^ a b Stavrakopoulou 2013, p. 145.

- ^ Dewrell 2017, pp. 30–35.

- ^ Reynolds 2007, pp. 146–150.

- ^ Dewrell 2016, pp. 496–499.

- ^ Lange 2007, p. 127.

- ^ Frendo 2016, pp. 363–364.

- ^ Dewrell 2017, pp. 144–146.

- ^ Dewrell 2017, p. 7.

- ^ Dewrell 2017, p. 20.

- ^ Xella 2013, pp. 265–266.

- ^ a b c d e Lockshin 2021.

- ^ Kasher 1988, p. 566.

- ^ Kugel 2012, p. 261.

- ^ Kugel 2012, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Rundin 2004, p. 430.

- ^ Moore 1897, p. 162.

- ^ a b Heider 1985, p. 2.

- ^ Gemeinhardt 2021.

- ^ a b Benjamin 2021.

- ^ Moore 1897, p. 161.

- ^ a b Chryssides 2021.

- ^ Moore 1897, p. 165.

- ^ Rundin 2004, pp. 430–432.

- ^ a b c d e Urban 2021.

- ^ a b Dewrell 2017, p. 5.

- ^ a b Kropp 2001, p. 183.

- ^ Bart 1984, p. 314.

- ^ Dewrell 2017, p. 10.

- ^ a b Becking 2014.

- ^ Dorgerloh 2013, p. 231–232.

- ^ Dorgerloh 2013, p. 237.

- ^ Dorgerloh 2013, p. 239.

Sources

[edit]- Bart, B. F. (1984). "Male Hysteria in "Salammbô". Nineteenth-Century French Studies. 12 (3): 313–321. JSTOR 23536541.

- Becking, Bob (2014). "Moloch". In Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew (ed.). The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Cinematic Monsters (Online). Ashgate Publishing.

- Benjamin, Katie (2021). "Molech, Moloch: III Christianity B Medieval Christianity and Reformation Era". In Furrey, Constance M.; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception. Vol. 19: Midrash and Aggada – Mourning. de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/ebr.molechmoloch. ISBN 978-3-11-031336-9. S2CID 245085818.

- Boysen, Knud Henryk; Ruwe, Andreas (2021). "Molech, Moloch: Christian: C Modern Europe and America". In Furrey, Constance M.; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception. Vol. 19: Midrash and Aggada – Mourning. de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/ebr.molechmoloch. ISBN 978-3-11-031336-9. S2CID 245085818.

- Chryssides, George D. (2021). "Molech, Moloch: Christian: D New Christian Churches and Movements". In Furrey, Constance M.; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception. Vol. 19: Midrash and Aggada – Mourning. de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/ebr.molechmoloch. ISBN 978-3-11-031336-9. S2CID 245085818.

- Day, John (2000). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 1-85075-986-3.

- Dewrell, Heath D. (2016). "A 'Molek' Inscription from the Levant?". Revue Biblique. 123 (4): 481–505. doi:10.2143/RBI.123.4.3180790. JSTOR 44809366.

- Dewrell, Heath D. (2017). Child sacrifice in ancient Israel. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575064949.

- Dorgerloh, Annette (2013). "Competing ancient worlds in early historical film: the example of Cabiria (1914)". In Michelakis, Pantellis; Wyke, Maria (eds.). The Ancient World in Silent Cinema. Cambridge University Press. pp. 229–246. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139060073.015. ISBN 9781139060073.

- Frendo, Anthony J. (2016). "Burning Issues: MLK Revisited". Journal of Semitic Studies. 61 (2): 347–364. doi:10.1093/jss/fgw020.

- Gemeinhardt, Peter (2021). "Molech, Moloch: III Christianity A Patristics and Orthodox Churches". In Furrey, Constance M.; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception. Vol. 19: Midrash and Aggada – Mourning. de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/ebr.molechmoloch. ISBN 978-3-11-031336-9. S2CID 245085818.

- Heider, G. C. (1985). The Cult of Molek: A Reassessment. JSOT Press. ISBN 1850750181.

- Heider, G. C. (1999). "Moloch". In Toorn, Karel van der; Becking, Bob; Horst, Pieter W. van der (eds.). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (2 ed.). Brill. pp. 581–585. doi:10.1163/2589-7802_DDDO_DDDO_Molech.

- Holm, Tawny L. (2005). "Phoenician Religion [Further Considerations]". In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 10 (2 ed.). Macmillan Reference. pp. 7134–7135.

- Kasher, Rimon (1988). "The Interpretation of Scripture in Rabbinic Literature". In Mulder, Martin-Jan (ed.). The Literature of the Jewish People in the Period of the Second Temple and the Talmud, Volume 1 Mikra. Brill. pp. 547–594. doi:10.1163/9789004275102_016. ISBN 9789004275102.

- Kerr, R.M. (2018). "In Search of the Historical Moloch". In Kerr, R.M.; Schmitz, Philip C.; Miller, Robert (eds.). "His Word Soars Above Him" Biblical and North-West Semitic Studies Presented to Professor Charles R. Krahmalkov. Ann Arbor. pp. 59–80.

- Kropp, Sonja Dams (2001). "PLASTICITY ANIMATED: FROM MOLOCH'S STATUE TO "SALAMMBÔ'S TEXT"". Romance Notes. 41 (2): 183–190. JSTOR 43802763.

- Kugel, James L. (2012). A Walk through Jubilees: Studies in the Book of Jubilees and the World of its Creation. Brill.

- Lange, Armin (2007). ""They Burn Their Sons and Daughters— That Was No Command of Mine" (Jer 7:31): Child Sacrifice in the Hebrew Bible and in the Deuteronomistic Jeremiah Redaction". In Finsterbusch, Karin; Lange, Armin; Römheld, Diethold (eds.). Human sacrifice in Jewish and Christian tradition. Brill. pp. 109–132. ISBN 978-9004150850.

- Lockshin, Martin (2021). "Molech, Moloch: II Judaism". In Furrey, Constance M.; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception. Vol. 19: Midrash and Aggada – Mourning. de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/ebr.molechmoloch. ISBN 978-3-11-031336-9. S2CID 245085818.

- Mosca, Paul (1975). Child Sacrifice in Canaanite and Israelite Religion (Thesis). Harvard University.

- Moore, George Foot (1897). "Biblical Notes". Journal of Biblical Literature. 16 (1/2): 155–165. doi:10.2307/3268874. JSTOR 3268874.

- Pietersma, Albert; Wright, Benjamin, eds. (2014). "New English Translation of the Septuagint: Electronic Version". Oxford University Press.

- Reynolds, Bennie H. (2007). "Molek: Dead or Alive? The Meaning and Derivation of mlk and מלך". In Finsterbusch, Karin; Lange, Armin; Römheld, Diethold (eds.). Human sacrifice in Jewish and Christian tradition. Brill. pp. 133–150. ISBN 978-9004150850.

- Rundin, John S. (2004). "Pozo Moro, Child Sacrifice, and the Greek Legendary Tradition". Journal of Biblical Literature. 123 (3): 425–447. doi:10.2307/3268041. JSTOR 3268041.

- Reich, Bo (1993). "Gehenna". In Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199891023.

- Schmidt, Brian B. (2021). "Molech, Moloch: I Hebrew Bible/Old Testament". In Furrey, Constance M.; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception. Vol. 19: Midrash and Aggada – Mourning. de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/ebr.molechmoloch. ISBN 978-3-11-031336-9. S2CID 245085818.

- Soltes, Ori Z. (2021). "Molech, Moloch: V Visual Arts and Film". In Furrey, Constance M.; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception. Vol. 19: Midrash and Aggada – Mourning. de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/ebr.molechmoloch. ISBN 978-3-11-031336-9. S2CID 245085818.

- Stavrakopoulou, Francesca (2013). "The Jerusalem Tophet Ideological Dispute and Religious Transformation". Studi Epigrafici e Linguistici. 30: 137–158.

- Urban, David V. (2021). "Molech, Moloch: IV Literature". In Furrey, Constance M.; et al. (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Bible and its Reception. Vol. 19: Midrash and Aggada – Mourning. de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/ebr.molechmoloch. ISBN 978-3-11-031336-9. S2CID 245085818.

- Werse, Nicholas R. (2018). "Of Gods and Kings: The Case for Reading "Milcom" in Zephaniah 1:5bβ". Vetus Testamentum. 68 (3): 503–513. doi:10.1163/15685330-12341328.

- Xella, P. (2013). ""Tophet": an Overall Interpretation". In Xella, P. (ed.). The Tophet in the Ancient Mediterranean. Essedue. pp. 259–281.

External links

[edit]Moloch

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Terminology

Linguistic Origins

The term "Moloch," rendered in English from the Hebrew Bible's מֹלֶךְ (transliterated as mōleḵ or mōlek), derives from the Semitic triliteral root mlk, which fundamentally connotes rulership or kingship across ancient Near Eastern languages including Hebrew, Phoenician, Ugaritic, and Aramaic.[6] This root appears in cognates such as the Hebrew melek (מֶלֶךְ, "king") and Phoenician mlk ("king" or "to rule"), reflecting a shared Northwest Semitic linguistic heritage where mlk denotes authority figures or divine sovereignty.[7] In the Hebrew Masoretic Text, the vocalization of מֹלֶךְ employs a ḥolem (o-sound) under the mem and a segol (short e) under the lamed and kaph, diverging from the standard melek pattern of two segols (e-e), a pointed distinction likely introduced by Masoretic scribes around the 7th–10th centuries CE to preserve pronunciation amid theological sensitivities.[1] This altered pointing has prompted scholarly analysis of intentional phonetic modification: since the 19th century, following Abraham Geiger's 1857 proposal, the form is viewed as a deliberate "tendentious misvocalization" of melek, prefixing mlk and shifting vowels to evoke disdain, potentially blending the consonants of "king" with the vowels of bošet (בֹּשֶׁת, "shame"), a common biblical device for desecrating pagan elements.[1] [8] The Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible completed by ca. 100 BCE, renders מֹלֶךְ variably as Molokh (Μολόχ) or archōn ("ruler"), underscoring the term's perceived royal connotation while adapting it to Hellenistic contexts.[9] Extrabiblical attestations, such as Punic inscriptions from Carthage (ca. 800–146 BCE) using mlk in sacrificial contexts, suggest the root's extension beyond mere kingship to ritual acts in Phoenician dialects, though direct equivalence to the Hebrew form remains debated due to dialectal variations.[1]Interpretations of "Molk" vs. "Melek"

The Hebrew term underlying "Moloch" derives from the consonantal root mlk, which typically vocalizes as melek ("king") in standard usage, but appears as mōlek in biblical contexts referring to prohibited rites.[10] Traditional interpretations, rooted in ancient rabbinic and early scholarly views, treat mōlek as the proper name of a Canaanite-Ammonite deity, akin to "the king," possibly an epithet for a fire or underworld god demanding child offerings, distinguishing it from mere royal terminology.[11] This view aligns with passages like Leviticus 18:21, where "passing seed to Molech" implies dedication to a divine entity rather than an abstract rite.[12] A contrasting interpretation, advanced by Otto Eissfeldt in 1935 and subsequently supported by linguists examining Punic and Phoenician inscriptions, posits molk (or mlk) not as a deity but as a technical term for a votive sacrifice, often involving human immolation to fulfill a vow or avert calamity.[1] In Carthaginian contexts, mlk denotes child dedication by fire, evidenced in tophet stelae and texts where it functions as a noun for the offering type, rendering biblical phrases like "lemlk" as "as a molk" rather than "to the Moloch."[10] This etymology traces to a Semitic root √mlk II (distinct from melek), implying "to offer" or "consecrate," with Syriac parallels confirming non-deific sacrificial usage.[13] The debate hinges on vocalization and context: Masoretic pointing inserts vowels to differentiate mōlek from melek, potentially to avoid sacralizing kingship or to euphemize a rite, but Punic evidence favors the sacrifice reading over independent deity status.[1] Scholars like Heath Dewrell argue the vow-association strengthens the molk-as-rite view, minimizing direct ties to melek, though some, including Moshe Weinfeld, propose non-lethal interpretations like symbolic passage through fire, which lack broad empirical support from archaeological fire-pits and urns.[14] While the deity interpretation persists in theological traditions, linguistic and epigraphic data increasingly substantiate molk as denoting a sacrificial category, not a named god, reflecting Canaanite practices adapted or condemned in Israelite texts.[10]Biblical and Historical Attestations

References in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible condemns the practice of offering children to Molech, portraying it as a form of idolatry involving passage through fire, often in the Valley of Hinnom (Gehenna).[15] Leviticus 18:21 explicitly prohibits: "You shall not give any of your offspring to offer them to Molech, nor shall you profane the name of your God: I am the LORD," framing the act as a defilement of divine holiness amid broader laws against Canaanite abominations.[16] Leviticus 20:2–5 further details penalties, stating that any Israelite or resident alien who "gives any of his offspring to Molech shall surely be put to death" by stoning, with communal responsibility if overlooked, emphasizing Molech worship as a capital offense that risks divine wrath on the nation. Historical narratives in the Books of Kings attribute Molech veneration to Israelite kings influenced by foreign wives or alliances. In 1 Kings 11:7, Solomon constructs a high place for "Molech, the abomination of the Ammonites," on the hill east of Jerusalem, contributing to the division of the kingdom as divine judgment for idolatry.[17] 2 Kings 23:10 records King Josiah's reforms, where he "defiled Topheth, which is in the Valley of the Son of Hinnom, that no one might burn his son or his daughter as an offering to Molech," linking the site to ritual immolation and portraying Josiah's desecration as restoration of Yahweh's covenant. Prophetic texts reinforce these condemnations, attributing child sacrifice to Molech as apostasy provoking exile. Jeremiah 32:35 denounces Judah's kings and people for building "high places of Baal in the Valley of Hinnom" to "burn offerings to Molech," declaring it an uncommanded detestable act never contemplated by God.[18] Amos 5:26 accuses Israel of bearing "the tabernacle of your Moloch and Kiyyun, your images, the star of your gods which you made for yourselves," associating it with astral worship and foreshadowing captivity beyond Damascus. These passages collectively depict Molech as a foreign deity whose cult, centered on infant holocausts, symbolized Israel's rebellion against exclusive Yahweh devotion.[14]References in the Septuagint and New Testament

In the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible completed between the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, the term mōlek from the Hebrew text is rendered variably, often avoiding a direct transliteration as a proper name. In prohibitions against child sacrifice in Leviticus 18:21 and 20:2–5, it is translated as archōn ("ruler") rather than a deity's name, reflecting an interpretation of mōlek as a title denoting authority or kingship rather than an independent god.[19] Similarly, in 1 Kings 11:7, describing Solomon's construction of a high place for "Molech," the Septuagint uses basileus ("king"), aligning with scholarly views that mōlek derives from the Semitic root for "king" (mlk), potentially indicating a sacrificial rite or epithet rather than a distinct entity.[20] This translational choice may stem from efforts to distance the term from idolatrous connotations or to emphasize its generic meaning, as evidenced by the consistent use of such equivalents in the Pentateuchal passages.[1] A notable exception appears in Amos 5:26, where the Septuagint explicitly transliterates the term as Molokh (Μολὸχ), referring to the "tabernacle of Moloch" (skēnēn tou Molokh) alongside the "star of your god Raiphan," condemning Israelite idolatry during wilderness wanderings.[21] This rendering introduces Molokh as a cultic object or idol, diverging from the more interpretive approach in Leviticus and influencing later Christian texts. The passage critiques the adoption of foreign astral and sacrificial practices, portraying them as portable tabernacles carried in worship.[22] The New Testament contains a single direct reference to Moloch, in Acts 7:43, part of Stephen's defense before the Sanhedrin circa 34 CE. Here, Stephen quotes Amos 5:26 from the Septuagint: "You took up the tent of Moloch and the star of your god Rephan, the images that you made to worship them; and I will carry you away beyond Babylon" (Acts 7:43, ESV).[23] This citation, using Molokh as in the Greek Amos, accuses the Israelites of persistent idolatry from the exodus period onward, linking it to their rejection of divine prophets and culminating in exile.[24] Unlike the Hebrew Masoretic Text's sikkût (possibly "tent" or a deity name, often rendered as Saturn in some traditions), the Septuagintal form adopted in Acts emphasizes Moloch as a specific idolatrous focus, reinforcing the speech's theme of covenant unfaithfulness without additional elaboration on the deity's nature.[25] No other New Testament passages mention Moloch, though the broader context echoes Old Testament condemnations of child sacrifice and foreign cults.[26]Associated Practices of Child Sacrifice

Biblical texts describe child sacrifice to Molech as involving the ritual of passing children through fire, a practice explicitly prohibited in Leviticus 18:21, which states, "You shall not give any of your offspring to offer them to Molech, nor shall you profane the name of your God."[2] This rite is further detailed in Leviticus 20:2-5, mandating death by stoning for any Israelite who gives a child to Molech, indicating the act entailed the child's death as an offering.[27] Historical interpretations, including rabbinic sources, suggest the method involved placing the child on the heated outstretched arms of a statue, causing it to roll into a fire pit below, though the Bible itself emphasizes the fiery consumption without specifying the idol's form.[14] In the kingdoms of Judah and Israel, kings such as Ahaz and Manasseh are recorded as having sacrificed their own sons in this manner, emulating Canaanite customs condemned as detestable.[1] The site of these sacrifices was often the Topheth in the Valley of Hinnom near Jerusalem, where Jeremiah 32:35 accuses the people of building high places to Molech for burning sons and daughters in fire, a practice Josiah later sought to eradicate by defiling the area in 622 BCE.[4] These acts were tied to vows or averting calamity, reflecting a broader Canaanite-Phoenician tradition of infant immolation to deities like Baal, with Molech specifically invoked in Ammonite and Judean contexts.[2] Archaeological parallels in Phoenician colonies, particularly Carthage, reveal tophet sanctuaries containing thousands of cremated infant remains from the 8th century BCE onward, deposited in urns with inscriptions dedicating them to Baal Hammon and Tanit—deities sometimes equated with Molech equivalents.[28] Isotopic analysis of teeth from these sites confirms the children were not victims of natural mortality spikes but were deliberately sacrificed, often weeks old, supporting ancient accounts by Greek and Roman historians like Diodorus Siculus of mass child burnings during crises.[29] While direct epigraphic evidence for "Molech" in these tophets is absent, the rite's fiery dedication of firstborn or vowed children mirrors biblical prohibitions, indicating a shared Semitic practice disseminated from Canaanite origins.[3]Archaeological Evidence

Tophet Sites in Carthage and Phoenicia

The Tophet of Carthage, situated in the Salammbô district of ancient Carthage (modern Tunisia), functioned as an open-air sanctuary dedicated to the Punic deities Tanit and Baal Hammon, where rituals involving the cremation of infants occurred from the late 8th century BCE until the Roman destruction in 146 BCE.[4] [30] Archaeological excavations since the 19th century have revealed over 20,000 cinerary urns interred in layers beneath engraved stelae, primarily containing the charred bones of newborns and infants mostly under three months old, with both sexes represented in roughly equal proportions.[31] [28] The urns, often made of pottery or amphorae, occasionally include faunal remains such as sheep or goats, interpreted as substitute offerings when human infants were unavailable.[32] Stelae inscriptions frequently reference mlk ('offering' or 'sacrifice') vows to the gods, such as "To the lady Tanit face of Baal and to Baal Hammon, the vow which [name] vowed because he heard his voice," linking the site to Phoenician-Punic sacrificial practices dedicated to Baal-Hammon and Tanit.[4] [32] Osteological studies of remains from hundreds of urns demonstrate peri-natal ages with minimal variation, inconsistent with natural infant mortality rates that would show greater age diversity and higher stillbirth proportions; dental enamel analysis further confirms live births followed by cremation at temperatures exceeding 700°C.[28] [33] A 2014 interdisciplinary study led by Paolo Xella et al. confirmed through such analyses that these were ritual sacrifices of healthy newborns, not mere burials of naturally deceased children, reflecting broader Phoenician practices likely rooted in Canaanite traditions.[28] [33] While some scholars propose the Tophet as a dedicated infant cemetery for naturally deceased children, the uniformity of cremation, exclusion of older children or adults, and epigraphic evidence of vows fulfilled through sacrifice support the interpretation of systematic child immolation as a rite to avert disaster or secure divine favor.[4] [33] Comparable tophet precincts appear in other Phoenician colonial sites across the western Mediterranean, including Motya and Eryx in Sicily, Sulcis and Tharros in Sardinia, and Nora in Sardinia, dating from the 8th to 3rd centuries BCE, with similar urn deposits of infant remains under inscribed stelae evoking Tanit and Baal Hammon.[34] [35] These coastal sanctuaries, often positioned outside city walls to the north, yielded thousands of urns collectively, with faunal proxies and charcoal residues indicating pyre-based rituals mirroring Carthage.[36] In Phoenicia proper (modern Lebanon), direct tophet equivalents are scarce due to limited excavation, but Canaanite precursors in sites like Tyre and Sidon suggest the practice stemmed from Bronze Age Levantine traditions of child offerings to Baal deities, transmitted via Phoenician expansion.[35] [32] The persistence of these sites into the Hellenistic period underscores their role in Punic religious continuity, despite Roman prohibitions post-conquest.[30]Findings in the Levant and Israel

Archaeological investigations in the Levant, encompassing modern-day Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan, have yielded limited direct evidence of child sacrifice practices linked specifically to Moloch worship, unlike the well-documented tophet sites in Carthage and other Punic areas. No direct archaeological evidence of Tophet sites or comparable child sacrifice remains has been found in the Levant, despite biblical attestations of "passing children through fire" to Moloch. While biblical texts describe such rites occurring in the Valley of Hinnom (Gehenna) near Jerusalem, where children were purportedly passed through fire to Molech, no physical remains of sacrificial altars or mass infant burials have been uncovered at this location despite extensive excavations.[2][37] Scholars note that the valley later served as a refuse dump, potentially obscuring earlier ritual evidence, but the absence of confirmatory artifacts persists, highlighting the evidential distinction from Punic contexts.[4] In Israel proper, potential indicators of child sacrifice appear at sites like Gezer, a Canaanite city with a large ritual high place featuring standing stones and basins, where excavations revealed human remains suggestive of sacrificial practices, including those of young individuals. This Canaanite high place, dated to the Late Bronze Age around 1500–1200 BCE, included evidence of animal and possibly human offerings, aligning with broader regional patterns of devotion to deities demanding extreme propitiation. However, these findings are not explicitly tied to Moloch, as the term "Molek" emerges primarily in Iron Age Israelite contexts, and interpretations remain contested among archaeologists who caution against over-attributing isolated bones to ritual killing without contextual crematoria or urn fields.[38][3] Broader Levantine evidence includes urn burials in open-air sanctuaries at two proposed sites tentatively labeled as proto-tophets due to similarities with Punic structures, such as infant cremations in jars accompanied by votive offerings, potentially dating to the Phoenician period (circa 1000–500 BCE). These features echo the Carthaginian tophets but lack dedicatory inscriptions invoking Tanit or Baal-Hammon equivalents directly paralleling Molech. No securely identified tophet precincts exist in the Levant, leading researchers to infer that while child sacrifice occurred as a sporadic or crisis-driven rite among Canaanites and Phoenicians—corroborated by ancient texts like those of Philo of Byblos—systematic Moloch-specific installations akin to those in the western Mediterranean are absent.[39][40] This scarcity may reflect cultural adaptations, destruction by Israelite reformers, or interpretive biases in excavation priorities favoring monumental over ritual peripheries.[41]Scholarly Theories and Debates

Moloch as an Independent Deity

The theory that Moloch constituted an independent deity originates from the traditional interpretation of biblical texts, where the name appears as a proper noun denoting a specific god demanding child sacrifice by fire.[1] In passages such as Leviticus 18:21 and 20:2–5, Yahweh prohibits Israelites from "passing [their] offspring through the fire to Molech," framing it as worship of a foreign deity akin to Baal or Chemosh, rather than a mere ritual term.[42] Similarly, 1 Kings 11:7 describes King Solomon constructing a high place for "Molech, the abomination of the Ammonites," positioning Moloch as the patron god of Ammon, distinct from neighboring deities like Moab's Chemosh.[43] This view posits Moloch as a chthonic or fertility-related figure in the Canaanite-Ammonite pantheon, whose cult involved tophet-style immolation to ensure agricultural prosperity or avert calamity, as inferred from prophetic condemnations in Jeremiah 32:35 and 2 Kings 23:10, where King Josiah defiles the site of Molech worship in the Valley of Hinnom.[29] Scholars upholding this interpretation, such as those prior to the mid-20th century shift, argue that the consistent biblical phrasing—"to Molech"—mirrors invocations of other autonomous gods, implying a theological entity with its own cultic identity, potentially vocalized as mōlek from a Semitic root denoting kingship or counsel.[44] Although direct epigraphic evidence for a deity named Moloch remains absent outside the Bible, proponents cite parallels in Ammonite onomastics and Punic inscriptions using mlk in divine contexts, suggesting it functioned as a theonym rather than solely a sacrificial descriptor.[45] Distinctions from Milcom, the attested Ammonite high god (e.g., 1 Kings 11:5, 33), reinforce independence, as 2 Kings 23:13 lists their shrines separately, indicating Moloch held a subordinate yet specific role, possibly as an underworld or destructive aspect of the pantheon.[42] This perspective contrasts with later theories equating Moloch to Milcom via vocalization differences but maintains that biblical rhetoric treats it as a unique abominable entity, evidenced by its standalone prohibitions.[43] ![Idol of Moloch][float-right]Depictions of Moloch idols, such as those in ancient art showing bull-headed figures, align with this theory by visualizing a humanoid divine form receiving offerings, consistent with biblical inferences of a localized cult object in Jerusalem's environs. While archaeological tophets in Carthage yield infant remains dedicated to Baal-Hammon (with mlk notations), Levantine sites like Gezer show fire-damaged child bones from the Iron Age, interpretable as Moloch rites if the deity theory holds, though attribution relies on biblical correlation rather than inscriptions.[4] Critics note the scarcity of non-biblical attestations, yet the theory's endurance stems from the Hebrew Bible's portrayal of Moloch as a rival power inciting Israelite apostasy, demanding empirical rejection through Josiah's reforms circa 622 BCE.[1]