Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Synoptic Gospels

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| Bible |

|---|

|

|

Outline of Bible-related topics |

The gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke are referred to as the synoptic Gospels because they include many of the same stories, often in a similar sequence and in similar or sometimes identical wording. They stand in contrast to John, whose content is largely distinct. The term synoptic (Latin: synopticus; Greek: συνοπτικός, romanized: synoptikós) comes via Latin from the Greek σύνοψις, synopsis, i.e. "(a) seeing all together, synopsis".[n 1] The modern sense of the word in English is of "giving an account of the events from the same point of view or under the same general aspect".[2] It is in this sense that it is applied to the synoptic gospels.

This strong parallelism among the three gospels in content, arrangement, and specific language is widely attributed to literary interdependence,[3] though the role of orality and memorization of sources has also been explored by scholars.[4][5] The question of the precise nature of their literary relationship—the synoptic problem—has been a topic of debate for centuries and has been described as "the most fascinating literary enigma of all time".[6] While no conclusive solution has been found yet, the longstanding majority view favors Marcan priority, in which both Matthew and Luke have made direct use of the Gospel of Mark as a source, and further holds that Matthew and Luke also drew from an additional hypothetical document, called Q,[7] though alternative hypotheses that posit direct use of Matthew by Luke or vice versa without Q are increasing in popularity within scholarship.[8][9]

The synoptic gospels are similar to John; all are composed in Greek, have a similar length, and were completed in less than a century after Jesus' death. However, they differ from non-canonical sources such as the Gospel of Thomas in that they belong to the ancient genre of biography.[10][11] The patterns of parallels and variations found in the gospels are typical of ancient biographies about real people and history.[12]

Structure

[edit]Common features

[edit]Broadly speaking, the synoptic gospels are similar to John: all are composed in Koine Greek, have a similar length, and were completed in less than a century after Jesus' death. They also differ from non-canonical sources, such as the Gospel of Thomas, in that they belong to the ancient genre of biography,[13][14] collecting not only Jesus' teachings, but recounting in an orderly way his origins, ministry, Passion, miracles and Resurrection. The patterns of parallels and variations found in the gospels are typical of ancient biographies about real people and history.[15]

In content and in wording, though, the synoptics diverge widely from John but have a great deal in common with each other. Though each gospel includes some unique material, the majority of Mark and roughly half of Matthew and Luke coincide in content, in much the same sequence, often nearly verbatim. This common material is termed the triple tradition.

Triple tradition

[edit]The triple tradition, the material included by all three synoptic gospels, includes many stories and teachings:

- John the Baptist

- Baptism and temptation of Jesus

- First disciples of Jesus

- Hometown rejection of Jesus

- Healing of Peter's mother-in-law, demoniacs, a leper, and a paralytic

- Call of the tax collector

- New Wine into Old Wineskins

- Man with withered hand

- Commissioning the Twelve Apostles

- The Beelzebul controversy

- Teachings on the parable of the strong man, eternal sin, His true relatives, the parable of the sower, the lamp under a bushel, and the parable of the mustard seed

- Calming the storm

- The Gerasene demoniac

- The daughter of Jairus and the bleeding woman

- Feeding the 5000

- Confession of Peter

- Transfiguration

- The demoniac boy

- The little children

- The rich young man

- Jesus predicts his death

- Blind near Jericho

- Palm Sunday

- Casting out the money changers

- Render unto Caesar

- Woes of the Pharisees

- Second Coming Prophecy

- The Last Supper, passion, crucifixion, and entombment

- The empty tomb and resurrected Jesus

- Great Commission

The triple tradition's pericopae (passages) tend to be arranged in much the same order in all three gospels. This stands in contrast to the material found in only two of the gospels, which is much more variable in order.[16][17]

The classification of text as belonging to the triple tradition (or for that matter, double tradition) is not always definitive, depending rather on the degree of similarity demanded. Matthew and Mark report the cursing of the fig tree,[18][19] a single incident, despite some substantial differences of wording and content. In Luke, the only parable of the barren fig tree[20] is in a different point of the narrative. Some would say that Luke has extensively adapted an element of the triple tradition, while others would regard it as a distinct pericope.

Example

[edit]

An illustrative example of the three texts in parallel is the healing of the leper:[21]

| Mt 8:2–3 | Mk 1:40–42 | Lk 5:12–13 |

|---|---|---|

|

Καὶ ἰδοὺ, |

Καὶ ἔρχεται πρὸς αὐτὸν |

Καὶ ἰδοὺ, |

|

And behold, |

And, calling out to him, |

And behold, |

More than half the wording in this passage is identical. Each gospel includes words absent in the other two and omits something included by the other two.

Relation to Mark

[edit]

The triple tradition itself constitutes a complete gospel quite similar to the shortest gospel, Mark.[16]

Mark, unlike Matthew and Luke, adds little to the triple tradition. Pericopae unique to Mark are scarce, notably two healings involving saliva[22] and the naked runaway.[23] Mark's additions within the triple tradition tend to be explanatory elaborations (e.g., "the stone was rolled back, for it was very large"[24]) or Aramaisms (e.g., "Talitha kum!"[25]). The pericopae Mark shares with only Luke are also quite few: the Capernaum exorcism[26] and departure from Capernaum,[27] the strange exorcist,[28] and the widow's mites.[29] A greater number, but still not many, are shared with only Matthew, most notably the so-called "Great Omission"[30] from Luke of Mk 6:45–8:26.

Most scholars take these observations as a strong clue to the literary relationship among the synoptics and Mark's special place in that relationship,[31] though various scholars suggest an entirely oral relationship or a dependence emphasizing memory and tradents in a tradition rather than simple copying.[4][5][32] The Gospels represent a Jesus tradition and were enveloped by oral storytelling and performances during the early years of Christianity, rather than being redactions or literary responses to each other.[33] The hypothesis favored by most experts is Marcan priority, whereby Mark was composed first, and Matthew and Luke each used Mark, incorporating much of it, with adaptations, into their own gospels. Alan Kirk praises Matthew in particular for his "scribal memory competence" and "his high esteem for and careful handling of both Mark and Q", which makes claims the latter two works are significantly different in terms of theology or historical reliability dubious.[34][35] A leading alternative hypothesis is Marcan posteriority, with Mark having been formed primarily by extracting what Matthew and Luke shared in common.[36]

Double tradition

[edit]

An extensive set of material—some two hundred verses, or roughly half the length of the triple tradition—are the pericopae shared between Matthew and Luke, but absent in Mark. This is termed the double tradition.[38] Parables and other sayings predominate in the double tradition, but also included are narrative elements:[39]

- Preaching of John the Baptist

- Temptation of Jesus (which Mark summarizes in two verses)

- The Sermon on the Mount (Matthew) or Plain (Luke)

- The Centurion's servant

- Messengers from John the Baptist

- Woes to the unrepentant cities

- Jesus thanks his Father

- Return of the unclean spirit

- Parables of the leaven, the lost sheep, the great banquet, the talents, and the faithful servant

- Discourse against the scribes and Pharisees

- Lament over Jerusalem

Unlike triple tradition material, double tradition material is structured differently in the two gospels. Matthew's lengthy Sermon on the Mount, for example, is paralleled by Luke's shorter Sermon on the Plain, with the remainder of its content scattered throughout Luke. This is consistent with the general pattern of Matthew collecting sayings into large blocks, while Luke does the opposite and intersperses them with narrative.[40]

Besides the double tradition proper, Matthew and Luke often agree against Mark within the triple tradition to varying extents, sometimes including several additional verses, sometimes differing by a single word. These are termed the major and minor agreements (the distinction is imprecise[41][42]). One example is in the passion narrative, where Mark has simply, "Prophesy!"[43] while Matthew and Luke both add, "Who is it that struck you?"[44][45]

The double tradition's origin, with its major and minor agreements, is a key facet of the synoptic problem. The simplest hypothesis is Luke relied on Matthew's work or vice versa. But many experts, on various grounds, maintain that neither Matthew nor Luke used the other's work. If this is the case, they must have drawn from some common source, distinct from Mark, that provided the double-tradition material and overlapped with Mark's content where major agreements occur. This hypothetical document is termed Q, for the German Quelle, meaning "source".[46]

Special Matthew and Special Luke

[edit]Matthew and Luke contain a large amount of material found in no other gospel.[47] These materials are sometimes called "Special Matthew" or M and "Special Luke" or L.

Both Special Matthew and Special Luke include distinct opening infancy narratives and post-resurrection conclusions (with Luke continuing the story in his second book Acts). In between, Special Matthew includes mostly parables, while Special Luke includes both parables and healings.

Special Luke is notable for containing a greater concentration of Semitisms than any other gospel material.[48]

Luke gives some indication of how he composed his gospel in his prologue:[49][50]

Since many have undertaken to set down an orderly account of the events that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed on to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word, I too decided, after investigating everything carefully from the very first, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the truth concerning the things about which you have been instructed.[51]

Synoptic problem

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2021) |

The "synoptic problem" is the question of the specific literary relationship among the three synoptic gospels—that is, the question as to the source or sources upon which each synoptic gospel depended when it was written.

The texts of the three synoptic gospels often agree very closely in wording and order, both in quotations and in narration. Most scholars ascribe this to documentary dependence, direct or indirect, meaning the close agreements among synoptic gospels are due to one gospel's drawing from the text of another, or from some written source that another gospel also drew from.[52]

Controversies

[edit]The synoptic problem hinges on several interrelated points of controversy:

- Priority: Which gospel was written first? (If one text draws from another, the source must have been composed first.)

- Successive dependence: Did each of the synoptic gospels draw from each of its predecessors? (If not, the frequent agreements between the two independent gospels against the third must originate elsewhere.)

- Lost written sources: Did any of the gospels draw from some earlier document which has not been preserved (e.g., the hypothetical "Q", or from earlier editions of other gospels)?

- Oral sources: To what extent did each evangelist or literary collaborator[53] draw from personal knowledge, eyewitness accounts, liturgy, or other oral traditions to produce an original written account?

- Translation: Jesus and others quoted in the gospels spoke primarily in Aramaic, but the gospels themselves in their oldest available form are each written in Koine Greek. Who performed the translations, and at what point?

- Redaction: How and why did those who put the gospels into their final form expand, abridge, alter, or rearrange their sources?

Some[which?] theories try to explain the relation of the synoptic gospels to John; to non-canonical gospels such as Thomas, Peter, and Egerton; to the Didache; and to lost documents such as the Hebrew logia mentioned by Papias, the Jewish–Christian gospels, and the Gospel of Marcion.

History

[edit]

Ancient sources virtually unanimously ascribe the synoptic gospels to the apostle Matthew, to Mark, and to Luke—hence their respective canonical names.[54] The ancient authors, however, did not agree on which order the Gospels had been written. For example, Clement of Alexandria held that Matthew wrote first, Luke wrote second and Mark wrote third;[55] on the other hand, Origen argued that Matthew wrote first, Mark wrote second and Luke wrote third;[56] Tertullian states that John and Matthew were published first and that Mark and Luke came later;[57][58] and Irenaeus precedes all these and orders his famous 'four pillar story' by John, Luke, Matthew, and Mark.[59]

A remark by Augustine of Hippo at the beginning of the fifth century presents the gospels as composed in their canonical order (Matthew, Mark, Luke, John), with each evangelist thoughtfully building upon and supplementing the work of his predecessors—the Augustinian hypothesis (Matthew–Mark).[60]

This view (when any model of dependence was considered at all) seldom came into question until the late eighteenth century, when Johann Jakob Griesbach published in 1776 a synopsis of the synoptic gospels. Instead of harmonizing them, he displayed their texts side by side, making both similarities and divergences apparent. Griesbach, noticing the special place of Mark in the synopsis, hypothesized Marcan posteriority and advanced (as Henry Owen had a few years earlier[61]) the two-gospel hypothesis (Matthew–Luke).

In the nineteenth century, researchers applied the tools of literary criticism to the synoptic problem in earnest, especially in German scholarship. Early work revolved around a hypothetical proto-gospel (Ur-Gospel), possibly in Aramaic, underlying the synoptics. From this line of inquiry, however, a consensus emerged that Mark itself served as the principal source for the other two gospels—Marcan priority.

In a theory first proposed by Christian Hermann Weisse in 1838, the double tradition was explained by Matthew and Luke independently using two sources—thus, the two-source (Mark–Q) theory—which supplemented Mark with another hypothetical source consisting mostly of sayings. This additional source was at first seen as the logia (sayings) spoken of by Papias and thus called "Λ",[n 2] but later it became more generally known as "Q", from the German Quelle, meaning source.[62] This two-source theory eventually won wide acceptance and was seldom questioned until the late twentieth century; most scholars simply took this new orthodoxy for granted and directed their efforts toward Q itself, and this is still[update] largely the case.[citation needed]

The theory is also well known in a more elaborate form set forth by Burnett Hillman Streeter in 1924, which additionally hypothesized written sources "M" and "L" (for "Special Matthew" and "Special Luke" respectively)—hence the influential four-document hypothesis. This exemplifies the prevailing scholarship of the time, which saw the canonical gospels as late products, dating from well into the second century, composed by unsophisticated cut-and-paste redactors out of a progression of written sources, and derived in turn from oral traditions and from folklore that had evolved in various communities.[63]

In recent decades, weaknesses of the two-source theory have been more widely recognized,[by whom?] and debate has reignited. Many have independently argued that Luke did make some use of Matthew after all. British scholars went further and dispensed with Q entirely, ascribing the double tradition to Luke's direct use of Matthew—the Farrer hypothesis of 1955-which is enjoying growing popularity within scholarship today.[64][65] The rise of the Matthaean posteriority hypothesis, which dispenses with Q but ascribes the double tradition to Matthew's direct use of Luke, has been one of the defining trends of Synoptic studies during the 2010s, and the theory has entered the mainstream of scholarship.[66] Meanwhile, the Augustinian hypothesis has also made a comeback, especially in American scholarship. The Jerusalem school hypothesis has also attracted fresh advocates, as has the Independence hypothesis, which denies documentary relationships altogether.[citation needed]

On this collapse of consensus, Wenham observed: "I found myself in the Synoptic Problem Seminar of the Society for New Testament Studies, whose members were in disagreement over every aspect of the subject. When this international group disbanded in 1982 they had sadly to confess that after twelve years' work they had not reached a common mind on a single issue."[67]

More recently, Andris Abakuks applied a statistical time series approach to the Greek texts to determine the relative likelihood of these proposals. Models without Q fit reasonably well. Matthew and Luke were statistically dependent on their borrowings from Mark. This suggests at least one of Matthew and Luke had access to the other's work. The most likely synoptic gospel to be the last was Luke. The least likely was Mark. While this weighs against the Griesbach proposal and favors the Farrer, he does not claim any proposals are ruled out.[68]

Conclusions

[edit]No definitive solution to the Synoptic Problem has been found yet. The two-source hypothesis, which was dominant throughout the 20th century, still enjoys the support of most New Testament scholars; however, it has come under substantial attack in recent years by a number of biblical scholars, who have attempted to relaunch the Augustinian hypothesis,[69] the Griesbach hypothesis[70] and the Farrer hypothesis.[71]

In particular, the existence of the Q source has received strong criticism in the first two decades of the 21st century: scholars such as Mark Goodacre and Brant Pitre have pointed out that no manuscript of Q has ever been found, nor is any reference to Q ever made in the writings of the Church Fathers (or any ancient writings, in fact).[72][73][74] This has prompted E. P. Sanders and Margaret Davies to write that the Two-sources hypothesis, while still dominant, "is least satisfactory"[75] and Fr. Joseph Fitzmyer SJ to state that the Synoptic Problem is "practically insoluble".[76]

Theories

[edit]Nearly every conceivable theory has been advanced as a solution to the synoptic problem.[77] The most notable theories include:

| Priority | Theory[78] | Diagram | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

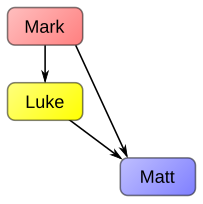

| Marcan priority |

Two‑source (Mark–Q) |

|

Most widely accepted theory. Matthew and Luke independently used Q, taken to be a Greek document with sayings and narrative. |

| Farrer (Mark–Matthew) |

|

Double tradition explained entirely by Luke's use of Matthew. | |

| Three‑source (Mark–Q/Matthew) |

|

A hybrid of Two-source and Farrer. Q may be limited to sayings, may be in Aramaic, and may also be a source for Mark. | |

| Wilke (Mark–Luke) |

|

Double tradition explained entirely by Matthew's use of Luke. | |

| Four-source (Mark–Q/M/L) |

|

Matthew and Luke used Q. Only Matthew used M and only Luke used L. | |

| Matthaean priority |

Two‑gospel (Griesbach) (Matthew–Luke) |

|

Mark primarily has collected what Matthew and Luke share in common (Marcan posteriority). |

| Augustinian (Matthew–Mark) |

|

The oldest known view, still advocated by some. Mark's special place is neither priority nor posteriority, but as the intermediate between the other two synoptic gospels. Canonical order is based on this view having been assumed (at the time when New Testament Canon was finalized). | |

| Lucan priority |

Jerusalem school (Luke–Q) |

|

A Greek anthology (A), translated literally from a Hebrew original, was used by each gospel. Luke also drew from an earlier lost gospel, a reconstruction (R) of the life of Jesus reconciling the anthology with yet another narrative work. Matthew has not used Luke directly. |

| Marcion priority | Priority of the Gospel of Marcion |

|

All gospels directly used the gospel of Marcion as their source, and have been influenced heavily by it. |

| Others or none | Multi‑source |

|

Each gospel drew from a different combination of hypothetical earlier documents. |

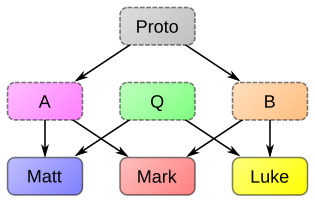

| Proto‑gospel |

|

The gospels each derive, all or some of, its material from a common proto-gospel (Ur-Gospel), possibly in Hebrew or Aramaic. | |

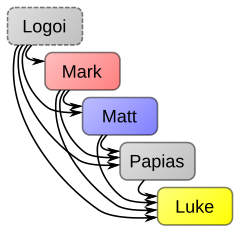

| Q+/Papias (Mark–Q/Matthew) |

|

Each document drew from each of its predecessors, including Logoi (Q+) and Papias' Exposition. | |

| Independence |

|

Each gospel is an independent and original composition based upon oral history. |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Both Greek words, synoptikos and synopsis, derive from σύν syn (prep.), meaning "together, with", and etymologically related words pertaining to sight, vision, appearance, i.e. ὀπτικός optikos (adj.; cf. English optic), meaning "of or for sight", and ὄψις opsis (n.), meaning "appearance, sight, vision, view".[2]

- ^ The capital form of the Greek letter lambda λ, corresponding to l, used here to abbreviate logia (Greek: λόγια).

References

[edit]- ^ Honoré, A. M. (1968). "A Statistical Study of the Synoptic Problem". Novum Testamentum. 10 (2/3): 95–147. doi:10.2307/1560364. ISSN 0048-1009. JSTOR 1560364.

- ^ a b "synoptic". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) Harper, Douglas. "synoptic". Online Etymology Dictionary. Harper, Douglas. "synopsis". Online Etymology Dictionary. Harper, Douglas. "optic". Online Etymology Dictionary. σύν, ὄπτός, ὀπτικός, ὄψις, συνοπτικός, σύνοψις. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Goodacre, Mark (2001). The Synoptic Problem: A Way Through the Maze. A&C Black. p. 16. ISBN 0567080560.

- ^ a b Derico, Travis (2018). Oral Tradition and Synoptic Verbal Agreement: Evaluating the Empirical Evidence for Literary Dependence. Pickwick Publications, an Imprint of Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 368–369. ISBN 978-1620320907.

- ^ a b Kirk, Alan (2019). Q in Matthew: Ancient Media, Memory, and Early Scribal Transmission of the Jesus Tradition. T&T Clark. pp. 148–183. ISBN 978-0567686541.

- ^ Goodacre (2001), p. 32.

- ^ Goodacre (2001), pp. 20–21.

- ^ Runesson, Anders (2021). Jesus, New Testament, Christian Origins. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802868923.

- ^ The Synoptic Problem 2022: Proceedings of the Loyola University Conference. Peeters Pub and Booksellers. 2023. ISBN 9789042950344.

- ^ Bauckham, Richard (2006). Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony. p. 220. ISBN 0802831621.

- ^ Perkins, Pheme (2009). Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 2–11. ISBN 978-0802865533.

- ^ Keener, Craig (2019). Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels. Eerdmans. p. 261. ISBN 978-0802876751.

- ^ Bauckham (2006), p. 220.

- ^ Perkins, Pheme (2009). Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 2–11. ISBN 978-0802865533.

- ^ Keener, Craig (2019). Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels. Eerdmans. p. 261. ISBN 978-0802876751.

- ^ a b Goodacre (2001), p. 38.

- ^ Neville, David (2002). Mark's Gospel – Prior Or Posterior?: A Reappraisal of the Phenomenon of Order. A&C Black. ISBN 1841272655.

- ^ Mt 21:18–22

- ^ Mk 11:12–24

- ^ Lk 13:6–9

- ^ Smith, Ben C. (2009). "The healing of a leper". TextExcavation. Archived from the original on May 1, 2006. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ^ Mk 7:33–36; 8:22–26

- ^ Mk 14:51–52

- ^ Mk 16:4

- ^ Mk 5:41

- ^ Mk 1:23–28, Lk 4:33–37

- ^ Mk 1:35–38, Lk 4:42–43

- ^ Mk 9:38–41, Lk 9:49–50

- ^ Mk 12:41–44, Lk 21:1–4

- ^ Stein, Robert H. (1992). Luke: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture. B&H Publishing. pp. 29–30. ISBN 0805401245.

- ^ Kloppenborg, John S. (2000). Excavating Q: The History and Setting of the Sayings Gospel. Fortress Press. pp. 20–28. ISBN 1451411553.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rafael (2017). "Matthew as Performer, Tradent, Scribe". Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus (15(2-3)): 192–212. doi:10.1163/17455197-01502003.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rafael (2010). Structuring Early Christian Memory: Jesus in Tradition, Performance and Text. T&T Clark. p. 5. ISBN 978-0567264206.

- ^ Kirk, Alan (2019). Q in Matthew: Ancient Media, Memory, and Early Scribal Transmission of the Jesus Tradition. T&T Clark. pp. 298–306. ISBN 978-0567686541.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rafael (2017). "Matthew as Performer, Tradent, Scribe". Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus (15(2-3)): 203. doi:10.1163/17455197-01502003.

- ^ Goodacre (2001), p. 81.

- ^ Mt 3:7–10 & Lk 3:7–9. Text from 1894 Scrivener New Testament.

- ^ Goodacre (2001), pp. 39 ff.

- ^ Goodacre (2001), pp. 40–41, 151–52.

- ^ Goodacre (2001), pp. 124–26.

- ^ Goodacre (2001), pp. 148–51.

- ^ Goodacre, Mark (2007-11-14). "Mark-Q Overlaps IV: Back to the Continuum". NT Blog. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ^ Mk 14:65

- ^ Mt 26:68, Lk 22:64

- ^ Goodacre (2001), pp. 145–46.

- ^ Goodacre (2001), p. 108.

- ^ Lace, O. Jessie (1965). Understanding the New Testament. The Cambridge Bible Commentary. Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 9780521092814.

- ^ Edwards, James R. (2009). The Hebrew Gospel and the Development of the Synoptic Tradition. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 141–48. ISBN 978-0802862341.

- ^ Bauckham (2006), pp. 65–66.

- ^ Alexander, Loveday (2005). The Preface to Luke's Gospel. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521018811.

- ^ Lk 1:1–4 (NRSV)

- ^ Goodacre, Mark (2013). "Synoptic Problem". In McKenzie, Steven L. (ed.). Oxford Encyclopedia of Biblical Interpretation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199832262.

- ^ Compare:

Watts, John (1860). Who Were the Writers of the New Testament?: The "evidence" Shown to be Untrustworthy Both as to the Time and Authors of the Several Gospels. London: George Abington. p. 9. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

Hennell, in his 'Origin of Christianity,' says that:- 'Some one after Matthew wrote the Greek Gospel which has come down to us, incorporating part of the Hebrew one, whence it was called the Gospel according to Matthew, and, in the second century, came to be considered as the work of the Apostle.'

- ^ Hengel, Martin (2000). The four Gospels and the one Gospel of Jesus Christ: an investigation of the collection and origin of the Canonical Gospels. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 34–115. ISBN 1563383004.

- ^ Eusebius, Church History, Book 6, Chapter 14, Paragraphs 6–10

- ^ Eusebius, Church History, Book 6, Chapter 25, Paragraphs 3–6

- ^ Tertullian, Against Marcion, Book 4, Chapter 5

- ^ Pitre, Brant (2016). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ. Crown Publishing Group. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0770435493.

- ^ Irenaeus, Against Heresies, Book 3, Chapter 11, Paragraph 8

- ^ Dungan, David L. (1999). A history of the synoptic problem: the canon, the text, the composition and the interpretation of the Gospels. pp. 112–144. ISBN 0385471920.

- ^ Owen, Henry (1764). Observations on the Four Gospels, tending chiefly to ascertain the time of their Publication, and to illustrate the form and manner of their Composition. London: T. Payne. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- ^ Lührmann, Dieter (1995). "Q: Sayings of Jesus or Logia?". In Piper, Ronald Allen (ed.). The Gospel Behind the Gospels: Current Studies on Q. pp. 97–102. ISBN 9004097376.

- ^ Goodacre (2001), pp. 160–161.

- ^ Farrer, A. M. (1955). "On Dispensing With Q". In Nineham, D. E. (ed.). Studies in the Gospels: Essays in Memory of R. H. Lightfoot. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 55–88. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

The literary history of the Gospels will turn out to be a simpler matter than we had supposed. St. Matthew will be seen to be an amplified version of St. Mark, based on a decade of habitual preaching, and incorporating oral material, but presupposing no other literary source beside St. Mark himself. St. Luke, in turn, will be found to presuppose St. Matthew and St. Mark, and St. John to presuppose the three others. The whole literary history of the canonical Gospel tradition will be found to be contained in the fourfold canon itself, except in so far as it lies in the Old Testament, the Pseudepigrapha, and the other New Testament writings. [...] Once rid of Q, we are rid of a progeny of nameless chimaeras, and free to let St. Matthew write as he is moved.

- ^ Runesson, Anders (2021). Jesus, New Testament, Christian Origins. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802868923.

- ^ The Synoptic Problem 2022: Proceedings of the Loyola University Conference. Peeters Pub and Booksellers. 2023. ISBN 9789042950344.

- ^ Wenham, John (1992). Redating Matthew, Mark, & Luke. InterVarsity Press. p. xxi. ISBN 0830817603.

- ^ Abakuks, Andris (2014). The Synoptic Problem and Statistics (1 ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC. ISBN 978-1466572010.

- ^ Wenham, John (1992). Redating Matthew, Mark and Luke: A Fresh Assault on the Synoptic Problem. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1725276642.

- ^ Black, David Alan (2010). Why Four Gospels?. Energion Publications. ISBN 978-1631992506.

- ^ Poirier, John C.; Peterson, Jeffrey (2015). Marcan Priority Without Q: Explorations in the Farrer Hypothesis. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0567367563.

- ^ Goodacre, Mark (2002). The Case Against Q: Studies in Markan Priority and the Synoptic Problem. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1563383342.

- ^ Goodacre, Mark S.; Perrin, Nicholas (2004). Questioning Q: A Multidimensional Critique. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0281056132.

- ^ Pitre, Brant (2016). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ. Crown Publishing Group. p. 97. ISBN 978-0770435493.

- ^ Sanders, E. P.; Davies, Margaret (1989). Studying the Synoptic Gospels. SCM Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0334023425.

- ^ Buttrick, David G. (1970). Jesus and Man's Hope. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. p. 132.

- ^ Carlson (September 2004). "Synoptic Problem". Hypotyposeis.org. Archived from the original on December 20, 2004. Carlson lists over twenty of the major ones, with citations of the literature.

- ^ Though eponymous and some haphazard structural names are prevalent in the literature, a systematic structural nomenclature is advocated by Carlson and Smith, and these names are also provided. The exception is the hypothesis of the priority of the Gospel of Marcion which is not part of their nomenclatures.

External links

[edit]- Catholic Encyclopedia: Synoptics

- Hypotyposeis: Synoptic Problem Website

- Synoptic Problem: Bibliography of the main studies in English

- TextExcavation: The Synoptic Project

- Synoptic Gospels Primer

- NT Gateway: Synoptic Problem Web Sites (archived 1 October 2019)

- The Synoptic Problem and its Solution (archived 20 October 2020)

- Matthew Conflator (Wilke) Hypothesis

- Synoptic Hypotheses and Authors (archived 5 September 2020)