Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

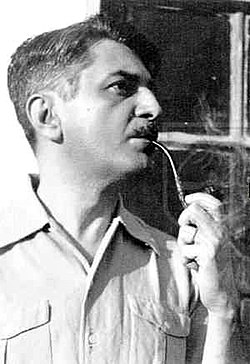

Gilberto Freyre

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (June 2010) |

Key Information

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Brazil |

|---|

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Eugenics |

|---|

Gilberto de Mello Freyre (March 15, 1900 – July 18, 1987) was a Brazilian sociologist, anthropologist, historian, writer, painter, journalist and congressman born in Recife. Considered one of the most important sociologists of the 20th century, his best-known work is a sociological treatise named Casa-Grande & Senzala (literally, "The main house and the slave quarters", usually translated into English as The Masters and the Slaves).

Life and work

[edit]Freyre had an internationalist academic career, having studied at Baylor University, Texas from the age of eighteen and then at Columbia University, where he got his master's degree under the tutelage of William Shepperd.[1] At Columbia, Freyre was a student of the anthropologist Franz Boas.[2] After coming back to Recife in 1923, Freyre spearheaded a handful of writers in a Brazilian regionalist movement. After working extensively as a journalist, he was made head of cabinet of the Governor of the State of Pernambuco, Estácio Coimbra. With the 1930 revolution and the rise of Getúlio Vargas, both Coimbra and Freyre went into exile. Freyre went first to Portugal and then to the US, where he worked as visiting professor at Stanford.[3] By 1932, Freyre had returned to Brazil. In 1933, Freyre's best-known work, The Masters and the Slaves was published and was well received.[citation needed] In 1946, Freyre was elected to the federal Congress.[4] At various times, Freyre also served as director of the newspapers A Província and Diário de Pernambuco.[5]

In 1962, Freyre was awarded the Prêmio Machado de Assis by the Brazilian Academy of Letters, one of the most prestigious awards in the field of Brazilian literature.[6] That same year, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[7] Over the course of his long career, Freyre received numerous other awards, honorary degrees, and other honors both in Brazil and internationally. Examples include admission to L'ordre des Arts et Lettres (France), investiture as Grand Officier de La Légion d'Honneur (France), the Gran-Cruz of the Ordem do Infante Dom Henrique (Portugal), and honorary doctorates at Columbia University and the Sorbonne.[8]

Freyre's most widely known work is The Masters and the Slaves (1933). At the time, this was a revolutionary work for the study of races and cultures in Brazil. As Lucia Lippi Oliveira notes, "In the 1930s and 1940s, Freyre was praised as being the creator of a new, positive self-image of Brazil, one that overcame the racism present in authors like Sílvio Romero, Euclides da Cunha, and Oliveira Viana."[9] The book misrepresents slavery in Brazil as a mild form of servitude and has served to consolidate the Brazilian myth of racial democracy. Freyre’s romanticization of racial mixture and disavowal of his society’s racism is comparable to the approach of other Latin American eugenicists, such as Fernando Ortiz in Cuba (Contrapunteo Cubano de Tobacco y Azúcar, 1940), and José Vasconcelos in Mexico (La Raza Cosmica, 1926).[10][11] Since its publication and initial reception, this work has also been criticized for how its "focus on a single identity in modern Brazil resulted not only in factual inaccuracies and distortions of reality but also in a larger societal refusal to acknowledge racism in modern Brazil,"[12] for example.

The Masters and the Slaves is the first of a series of three books, which also included The Mansions and the Shanties: The Making of Modern Brazil (1938) and Order and Progress: Brazil from Monarchy to Republic (1957). The trilogy is generally considered a classic of modern cultural anthropology and social history. Other very important contributions of Freyre's were The Northeast (1937) and The English in Brazil (1948).

The actions of Freyre as a public intellectual are rather controversial. Labeled as a communist in the 1930s, he later moved to the political Right. He supported Portugal's Salazar government in the 1950s, and after 1964, defended the military dictatorship of Brazil's Humberto Castelo Branco. Freyre is considered to be the "father" of lusotropicalism: the theory whereby miscegenation had been a positive force in Brazil. "Miscegenation" at that time tended to be viewed in a negative way, as in the theories of Eugen Fischer and Charles Davenport.[13]

Freyre was acclaimed for his literary style.[citation needed] Of his poem "Bahia of all saints and of almost all sins," Brazilian poet Manuel Bandeira wrote: "Your poem, Gilberto, will be an eternal source of jealousy to me"(cf. Manuel Bandeira, Poesia e Prosa. Rio de Janeiro: Aguilar, 1958, v. II: Prose, p. 1398).[14] Freyre wrote this long poem inspired by his first visit to Salvador.[citation needed]

Freyre died on July 18, 1987, in Recife.

Selected bibliography

[edit]- The Masters and the Slaves: a study in the development of Brazilian civilization – First published in Portuguese in 1933, under the title "Casa-Grande & Senzala".

- New World in the Tropics: the culture of modern Brazil

- The Mansions and the Shanties: the making of modern Brazil – First published in Portuguese in 1936, under the title "Sobrados e Mucambos".

- The Northeast: Aspects of Sugarcane Influence on Life and Landscape (1937)

- Sugar (1939)

- Olinda (1939)

- A French Engineer in Brazil (1940), second edition published in 1960

- Brazilian problems of Anthropology (1943)

- Continent and Island (1943)

- Sociology (1945)

- Brazil: an interpretation

- The English in Brazil, 1948

- Cape Verde Visited by Gilberto Freyre, 1956

- Order and Progress: Brazil from monarchy to republic

- Recife Yes, Recife No (1960)

- Poesia Reunida (1980)[15]

- Men, engineering and social routes (1987)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Vida – Honrarias". Biblioteca Virtual Gilberto Freyre. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ "Vida – Honrarias". Biblioteca Virtual Gilberto Freyre. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ "Vida – Honrarias". Biblioteca Virtual Gilberto Freyre. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ Gaspar, Lúcia. "Gilberto Freyre". Pesquisa Escolar Online, Fundação Joaquim Nabuco. Archived from the original on July 18, 2014. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ Gaspar, Lúcia. "Gilberto Freyre". Pesquisa Escolar Online, Fundação Joaquim Nabuco. Archived from the original on July 18, 2014. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ "Vida – Honrarias". Biblioteca Virtual Gilberto Freyre. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ "Vida – Honrarias". Biblioteca Virtual Gilberto Freyre. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ Oliveira, Lucia Lippi (2011). "Gilberto Freyre e a valorização da província". Sociedade e Estado (in Portuguese). 26: 117–149. doi:10.1590/S0102-69922011000100007. ISSN 0102-6992.

- ^ Milazzo, Marzia (October 15, 2022). Colorblind Tools: Global Technologies of Racial Power. Northwestern University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8101-4528-3.

- ^ Jr, Henry Louis Gates (August 1, 2012). Black in Latin America. NYU Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8147-3818-4.

- ^ Wohl, Emma (2013). ""Casa Grande e Senzala" and the Formation of a New Brazilian Identity". library.brown.edu. Retrieved July 27, 2021.

- ^ Gerald J. Bender, Angola under the Portuguese: The Myth and the Reality, Univ. of California Press, Berkeley, 1980, pp. xxiii, 5, 8

- ^ antoniomiranda.com.br

- ^ Omoniyi Afolabi (2022). "Gilberto Freyre: : The Poetic Optics of His Lusotropicalist Imagination". Brasiliana: Journal for Brazilian Studies. 11 (2): 98–136. ISSN 2245-4373. Wikidata Q117550411.

Bibliography

[edit]- Braga-Pinto, César. “Sugar Daddy: Gilberto Freyre and the white man’s love for blacks”. The Masters and the Slaves: Plantation Relations and Mestizaje in American Imaginaries. Palgrave, 2005, p. 19-33

- Braga-Pinto, César. “Os Desvios de Gilberto Freyre”. Novos Estudos – CEBRAP 76. São Paulo, Nov. 2006.

- Isfahani-Hammond, Alexandra (2005). White Negritude: Race, Writing, and Brazilian Cultural Identity (New Concepts in Latino American Cultures). Palgrave Macmillan Press. ISBN 1-4039-7595-7.

- Page, Joseph A. (1995), The Brazilians. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-201-44191-8.

- Gilberto Freyre Foundation – Gilberto Freyre's Virtual Library – https://web.archive.org/web/20070306124951/http://bvgf.fgf.org.br/

- Needell, Jeffrey D. "Identity, Race, Gender, and Modernity in the Origins of Gilberto Freyre's Oeuvre." The American Historical Review. 100.1 (February 1995):51–77.

- Stein, Stanley J. "Freyre's Brazil Revisited: A Review of the New World in the Tropics: The Culture of Modern Brazil." The Hispanic American Historical Review. 41.1 (February 1961):111–113

- Morrow, Glenn R. "Discussion of Dr. Gilberto Freyre's Paper." Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 4.2 (December 1943):176–177.

- Mazzara, Richard A. "Gilberto Freyre and Jose Honorio Rodrigues: Old and New Horizons for Brazil." Hispania. 47.2 (May 1964):316–325.

- Nery da Fonseca, Edson. Em Torno de Gilberto Freyre. Recife: Editora Massangana, 2007.

- Pallares-Burke, Maria Lúcia. Um Vitoriano dos Trópicos. São Paulo: Editora da Unesp, 2005.

- Sanchez-Eppler, Benigno "Telling Anthropology: Zora Neale Hurston Gilberto Freyre Disciplined in their Field-Home-Work." American Literary History. 4.3 (Autumn 1992):464–488.

- Villon, Victor. O Mundo Português que Gilberto Freyre Criou, seguido de Diálogos com Edson Nery da Fonseca. Rio de Janeiro, Vermelho Marinho, 2010.

- Burke, Peter / Pallares-Burke, Maria Lúcia G. Gilberto Freyre: Social Theory in the Tropics (The Past in the Present, 4). (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2008)

External links

[edit]- O Portal da História

- Gilberto Freyre virtual library

- Gilberto Freyre recorded at the Library of Congress for the Hispanic Division’s audio literary archive on March 30, 1975

- Gilberto Freyre recorded for the literary archive in the Hispanic Division at the Library of Congress. May 30, 1975 at the Library of Congress field office in Rio de Janeiro.