Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Questioned document examination

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

| Forensic science |

|---|

|

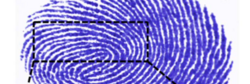

In forensic science, questioned document examination (QDE) is the examination of documents potentially disputed in a court of law. Its primary purpose is to provide evidence about a suspicious or questionable document using scientific processes and methods. Evidence might include alterations, the chain of possession, damage to the document, forgery, origin, authenticity, or other questions that come up when a document is challenged in court.

Overview

[edit]

Many QDE involve a comparison of the questioned document, or components of the document, to a set of known standards. The most common type of examination involves handwriting wherein the examiner tries to address concerns about potential authorship.

A document examiner is often asked to determine if a questioned item originated from the same source as the known item(s), then present their opinion on the matter in court as an expert witness. Other common tasks include determining what has happened to a document, determining when a document was produced, or deciphering information on the document that has been obscured, obliterated, or erased.

The discipline is known by many names including "forensic document examination", "document examination", "diplomatics", "handwriting examination", or sometimes "handwriting analysis", although the latter term is not often used as it may be confused with graphology. Likewise a forensic document examiner (FDE) is not to be confused with a graphologist, and vice versa.

Many FDEs receive extensive training in all of the aspects of the discipline. As a result, they are competent to address a wide variety of questions about document evidence. However, this "broad specialization" approach has not been universally adopted.

In some locales, a clear distinction is made between the terms "forensic document examiner" and a "forensic handwriting expert/examiner". In such cases, the former term refers to examiners who focus on non-handwriting examination types while the latter refers to those trained exclusively to do handwriting examinations. Even in places where the more general meaning is common, such as North America or Australia, there are many individuals who have specialized training only in relatively limited areas. As the terminology varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, it is important to clarify the meaning of the title used by any individual professing to be a "forensic document examiner".

Scope of document examination

[edit]A forensic document examiner is intimately linked to the legal system as a forensic scientist. Forensic science is the application of science to address issues under consideration in the legal system. FDEs examine items (documents) that form part of a case that may or may not come before a court of law.

Common criminal charges involved in a document examination case fall into the "white-collar crime" category. These include identity theft, forgery, counterfeiting, fraud, or uttering a forged document. Questioned documents are often important in other contexts simply because documents are used in so many contexts and for so many purposes. For example, a person may commit murder and forge a suicide note. This is an example where a document is produced directly as a fundamental part of a crime. More often a questioned document is simply the by-product of normal day-to-day business or personal activities.

For several years, the American Society for Testing and Materials, International (ASTM) published standards for many methods and procedures used by FDEs. E30.02 was the ASTM subcommittee for Questioned Documents. These guides were under the jurisdiction of ASTM Committee E30 on Forensic Sciences and the direct responsibility of Subcommittee E30.02 on Questioned Documents. When the ASTM Questioned Document subcommittee was disbanded in 2012 the relevant standards moved under the Executive Subcommittee E30.90; however, those standards have all been withdrawn over time.[1] Those standards, as well as links to updated versions of the documents, are presently available on the SWGDOC (The Scientific Working Group for Document Examiners) website.[2]

In 2015, the AAFS Standards Board (ASB) was formed to serve as a Standards Developing Organization (SDO). The ASB is an ANSI-accredited subsidiary of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences and the Forensic Document Examination Consensus Body within the ASB has published several relevant Standards.[3]

One of those is the Scope of Expertise in Forensic Document Examination document[4] which states an examiner needs "discipline specific knowledge, skills, and abilities" that qualifies them to conduct examinations of documents to answer questions about:

- the source(s) of writing;

- the source(s) of machine-produced documents;

- the source(s) of typewriting, impressions, and marks;

- the associations of materials and devices used to produce documents;

- the genuineness and authenticity of documents;

- the detection and decipherment of alterations, obliterations, and indentations, and;

- the preservation and restoration of legibility to damaged or illegible documents"[4]

Some FDEs limit their work to the examination and comparison of handwriting; most inspect and examine the whole document in accordance with this standard.

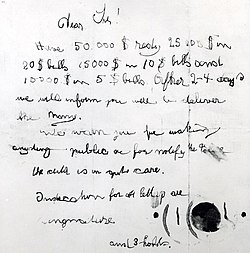

Types of document examined

[edit]Documents feature prominently in all manner of business and personal affairs. Almost any type of document may become disputed in an investigation or litigation. For example, a questioned document may be a sheet of paper bearing handwriting or mechanically-produced text such as a ransom note, a forged cheque, or a business contract. It may be material not normally thought of as a "document"; FDEs define the word "document" very broadly, as any material bearing marks, signs, or symbols intended to convey a message or meaning to someone. This includes, for example, graffiti on a wall, stamp impressions on meat products, and covert markings hidden in a written letter.

Historical and noteworthy cases

[edit]Pre-1900

[edit]- The Howland will forgery trial (1868)

- Although the crimes were committed before the discipline of document examination was firmly established, the letters of the Jack the Ripper case have since been examined in great detail

- The Dreyfus Affair (1894), involving non-FDE Alphonse Bertillon, although professional comparisons exonerating Dreyfus were ignored

- The James Reavis (Baron of Arizona) land swindle trial about forged documents involved in a Spanish barony and land grant (1895)

- The Adolf Beck cases (1896 and 1904) where handwriting expert Thomas H. Gurrin repeated an erroneous identification

1900-2000

[edit]- The Lindbergh kidnapping (1934) where comparison of the ransom note and Bruno Hauptmann's handwriting, by expert Albert S. Osborn, was crucial

- Operation Bernhard, a secret Nazi plan to destabilize the British economy through counterfeited banknotes (1939)

A £5 note (White fiver) forged by Sachsenhausen concentration camp prisoners as part of Operation Bernhard - Active measures, a Soviet-era political warfare program, led by the KGB, including the spreading of disinformation using falsified documents

- The Alger Hiss perjury appeal where the "fake typewriter hypothesis" saw expert Martin Tytell recreate a perfect replica typewriter (1952)

- The Zodiac Killer (1969)

Photo of victim Bryan Hartnell's car door, onto which the Zodiac Killer wrote details of his attack upon Hartnell and Cecelia Shepard - The Clifford Irving claim that Howard Hughes authorized his biography (1972)

- The Mormon Will that Melvin Dummar claimed left him part of Howard Hughes' fortune (1978)

- The Mark Hofmann forgeries and murders (1980–84)

- The Hitler Diaries printed by the magazine Stern and determined to be forgeries (1983)

- The Paul Jennings Hill murders (1994)

- The JonBenét Ramsey murder (1996)

Post-2000

[edit]- The anthrax attack mailings on the US Senate (2001)

- The Nina Wang case of the Teddy Wang wills (2002 and 2010)

- The Yellowcake Forgery (2003)

- The Killian memos (2004)

- The ImClone / Martha Stewart trial (2004)

- The National Archives forgeries (aka Martin Allen forgeries or Himmler forged documents) (2005)

- The Hassan Diab extradition hearing (2011)

- The Panama Papers document leak (2016) which led to numerous investigations world-wide, including the Panama Papers case (officially titled Imran Ahmed Khan Niazi v. Muhammad Nawaz Sharif) in which false documents were provided to the Supreme Court of Pakistan (2017)

Candidacy

[edit]A person who desires to enter a career of forensic document examination must possess certain traits and abilities. Requirements for the "Trainee Candidate" (Standard Guide for Minimum Training Requirements for Forensic Document Examiners) are listed in ASTM (E2388-11)[5] which has been moved to SWGDOC[6] (G02-13).

First and foremost, "an earned baccalaureate degree or equivalent from an accredited college or university" is required as it gives the aspirant a scientific background with which to approach the work in an objective manner, as well as bestowing necessary biological, physical, and chemical knowledge sometimes called upon in the work.

Second, excellent eyesight is required to see fine details that are otherwise inconspicuous. To this end, the aspirant must successfully complete:

- a form discrimination test to ensure that the aspirant is able to tell apart two similar-appearing yet different items,

- a color perception test, and

- near and distant visual acuity tests "with best corrected vision within six months prior to commencement of training."

Desirable skills also include knowledge of paper, ink, printing processes, and handwriting.

Training

[edit]There are three possible methods of instruction for an aspiring document examiner:

- Self-education is the way the pioneers of the field began, as there was no other method of instruction.

- Apprenticeship has become the widespread way many examiners are now taught. This is the method that is recommended by ASTM in Standard E2388-11[5] and SWGDOC G02-13.[6] To conform with these standards such training "shall be the equivalent of a minimum of 24 months full-time training under the supervision of a principal trainer" and "the training program shall be successfully completed in a period not to exceed four years". The training program must also include an extensive list of specific syllabus topics outlined in the relevant Standards.

- College and university programs are very limited, due in part to the relatively limited demand for forensic document examiners. It also relates to the need for extensive practical experience, particularly with respect to handwriting examination. It is difficult to include this degree of practical experience in a normal academic program.

There are some distance learning courses available as well. These are taught through a virtual reality classroom and may include an apprenticeship program, a correspondence course, or both.

A trainee must learn how to present evidence before the court in clear, forceful testimony. Fledgling examiners in the later stages of training can get a glimpse into the legal process as well as a better sense of this aspect of their work through participation in a mock trial or by attending court hearings to observe the testimony of qualified examiners. These are guidelines and not requirements.

Examination

[edit]Examination types

[edit]Examinations and comparisons conducted by document examiners can be diverse and may involve any of the following:

- Handwriting (cursive / printing) and signatures

- Typewriters, photocopiers, laser printers, ink-jet printers, fax machines

- Chequewriters, rubber stamps, price markers, label makers

- Printing processes

- Ink, pencil and paper

- Alterations, additions, erasures, obliterations

- Indentation detection and/or decipherment

- Sequence determination

- Physical matching

Principle of identification

[edit]The concept of 'identification' as it is applied in the forensic sciences is open to discussion and debate.[7] Nonetheless, the traditional approach in the discipline of forensic document examination is best expressed as follows:

"When any two items possess a combination of independent discriminating elements (characteristics) that are similar and/or correspond in their relationships to one another, of such number and significance as to preclude the possibility of their occurrence by pure coincidence, and there are no inexplicable disparities, it may be concluded that they are the same in nature or are related to a common source (the principle of identification)."[8]: 84

The evaluation of such characteristics is now predominantly subjective though efforts to meaningfully quantify this type of information are ongoing. Subjective evaluation does not mean that the results of properly conducted comparisons will be unreliable or inaccurate. To the contrary, scientific testing has shown that professional document examiners (as a group) out-perform lay-people when comparing handwriting or signatures to assess authorship.[9]

However, this type of subjective analysis depends greatly upon the competence of an individual examiner.

It follows that

- an examiner should follow appropriate case examination protocols carefully and evaluate all possible propositions,

- an examiner should be properly trained and their training should include adequate testing of their abilities,

- the formal case examination procedure should incorporate some form of secondary review (ideally, independent in nature) and

- every examiner should make every effort to demonstrate and maintain their competency through professional certification and ongoing proficiency testing.

Handwriting examinations

[edit]The examination of handwriting to assess potential authorship proceeds from the above principle of identification by applying it to a comparison of samples of handwritten material. Generally known as ACE-V, there are three stages in the process of examination.[8]

As Huber and Headrick explain in their text, these are as follows:[8]: 34

- Analysis or Discriminating Element Determination:

The unknown item and the known items must, by analysis, examination, or study, be reduced to a matter of their discriminating elements. These are the habits of behaviour or of performance (i.e., features or characteristics and, in other disciplines, the properties) that serve to differentiate between products or people which may be directly observable, measurable, or otherwise perceptible aspects of the item.

- Comparison:

The discriminating elements of the unknown, observed or determined through analysis, examination, or study, must be compared with those known, observed, or recorded of the standard item(s).

- Evaluation:

Similarities or dissimilarities in discriminating elements will each have a certain value for discrimination purposes, determined by their cause, independence, or likelihood of occurrence. The weight or significance of the similarity or difference of each element must then be considered and the explanation(s) for them proposed.

- Optionally, the procedure may involve a fourth step consisting of verification/validation or peer review.

The authors note further that "This process underlies the identification of any matter, person, or thing, by any witness, whether technical, forensic, or not." As such, it is not a formal method, but rather the elements that go into the method.

ASTM published a standard guide for the examination of handwriting titled "E2290-07a: Examination of Handwritten Items" which was withdrawn in 2016.[10] At that time, it was published as the SWGDOC Standard for Examination of Handwritten Items.[11] This was superseded in 2022 by the Academy Standards Board document Standard for Examination of Handwritten Items.[12] Some of the guides listed under "Other Examinations" below also apply to forensic handwriting comparisons (e.g., E444 or E1658).

An alternative guide for the examination of handwriting and signatures has been developed by the Forensic Expertise Profiling Laboratory (School of Human Biosciences, La Trobe University, Victoria, Australia).

The European Network of Forensic Science Institutes has also published a 'Best Practice Manual for the Forensic Handwriting Examination'.[13]

Other examinations

[edit]Aside from E2290 mentioned above, many standard guides pertaining to the examination of questioned documents were published by ASTM International.[1] They include the following:

- E0444-09 Scope of Work Relating to Forensic Document Examiners (Withdrawn 2018)[14]

- E2195-09 Terminology: Examination of Questioned Documents (Withdrawn 2018)[15]

- E1658-08 Terminology: Expressing Conclusions of Forensic Document Examiners (Withdrawn 2017)[16]

- E1422-05 Standard Guide for Test Methods for Forensic Writing Ink Comparison (Withdrawn 2014)[17]

- E1789-04 Writing Ink Identification (Withdrawn 2013)[17]

- E2285-08 Standard Guide for Examination of Mechanical Checkwriter Impressions (Withdrawn 2017)[18]

- E2286-08a Standard Guide for Examination of Dry Seal Impressions (Withdrawn 2017)[19]

- E2287-09 Standard Guide for Examination of Fracture Patterns and Paper Fiber Impressions on Single-Strike Film Ribbons and Typed Text (Withdrawn 2018)[20]

- E2288-09 Standard Guide for Physical Match of Paper Cuts, Tears, and Perforations in Forensic Document Examinations (Withdrawn 2018)[21]

- E2289-08 Standard Guide for Examination of Rubber Stamp Impressions (Withdrawn 2017)[22]

- E2291-03 E2291-03 Standard Guide for Indentation Examinations (Withdrawn 2012)[23]

- E2325-05e1 Standard Guide for Non-destructive Examination of Paper (Withdrawn 2014)[24]

- E2331-04 Standard Guide for Examination of Altered Documents (Withdrawn 2013)[25]

- E2388-11 Minimum Training Requirements for Forensic Document Examiners (Withdrawn 2020)[5]

- E2389-05 Standard Guide for Examination of Documents Produced with Liquid Ink Jet Technology (Withdrawn 2014)[26]

- E2390-06 Standard Guide for Examination of Documents Produced with Toner Technology (Withdrawn 2015)[27]

- E2494-08 Standard Guide for Examination of Typewritten Items (Withdrawn 2017)[28]

All withdrawn standards listed above have been taken over and are presently available on the SWGDOC (The Scientific Working Group for Document Examiners) website, including links to updated versions of the documents.[2]

Not all laboratories or examiners use or follow ASTM guidelines. These are guidelines and not requirements. There are other ASTM guides of a more general nature that apply (e.g., E 1732: Terminology Relating to Forensic Science). Copies of ASTM Standards can be obtained from ASTM International.

ANSI/ASB Standards and Guides for Questioned Documents are being published to replace previous ASTM/SWGDOC documents. As of 2023-12-25, the following have been published:[29]

- ANSI/ASB STANDARD 011 | QUESTIONED DOCUMENTS Scope of Expertise in Forensic Document Examination[30]

- ANSI/ASB STANDARD 035 | QUESTIONED DOCUMENTS Standard for the Examination of Documents for Alterations[31]

- ANSI/ASB STANDARD 044 | QUESTIONED DOCUMENTS Standard for Examination of Documents for Indentations[32]

- ANSI/ASB STANDARD 070 | QUESTIONED DOCUMENTS Standard for Examination of Handwritten Items[33]

- ANSI/ASB STANDARD 117 | QUESTIONED DOCUMENTS Standard for Examination of Stamping Devices and Stamp Impressions[34]

- ANSI/ASB STANDARD 127 | QUESTIONED DOCUMENTS Standard for the Preservation and Examination of Charred Documents[35]

- ANSI/ASB STANDARD 128 | QUESTIONED DOCUMENTS Standard for the Preservation and Examination of Liquid Soaked Documents[36]

- ANSI/ASB STANDARD 172 | QUESTIONED DOCUMENTS Standard for Examination of Mechanical Checkwriter Impressions and Machines[37]

Organization of scientific advisory committees (OSAC) Registry includes standards for Questioned Documents on the OSAC Registry.[38][39]

Common tools of the trade

[edit]- Excellent eyesight

- Handlens/loupe

- Stereomicroscope

- Electrostatic detection device (EDD)

- Video spectral comparator (VSC)

Professional organizations

[edit]Links are provided below

Dedicated to questioned document examination

[edit]- American Society of Questioned Document Examiners (ASQDE): USA and Canada

- Australasian Society of Forensic Document Examiners Inc. (ASFDE Inc): Australia/Asia (formerly the Australian Society of Forensic Document Examiners)[42]

- Associación Professional de Peritos Callígrafos de Cataluña (Spain)

- European Network of Forensic Handwriting Experts (ENFHEX within ENFSI)

- European Document Experts Working Group (EDEWG within ENFSI)

- Southeastern Association of Forensic Document Examiners (SAFDE): Southeast USA

- Southwestern Association of Forensic Document Examiners (SWAFDE): Southwest USA

- Gesellschaft für Forensische Schriftuntersuchung (GFS): Frankfurt (Germany)

- National Association of Document Examiners (NADE)

- Association of Forensic Document Examiners (AFDE)

- The International Association of Document Examiners (IADE)

- The Scientific Association of Forensic Examiners (SAFE)

- Sociedad Internacional de Peritos en Documentoscopia (SIPDO): Spain, Latin América

General forensic science associations with QDE sections

[edit]- American Academy of Forensic Sciences (AAFS): USA

- Canadian Society of Forensic Science (CSFS): Canada

- Australian and New Zealand Forensic Science Society (ANZFSS)

- European Network of Forensic Science Institutes (ENFSI)

- The Chartered Society of Forensic Sciences (formerly Forensic Science Society): United Kingdom

- International Association for Identification (IAI)

- Mid-Atlantic Association of Forensic Scientists (MAAFS)

Academic/research groups with interest in QDE

[edit]- International Graphonomics Society

- Center of Excellence for Document Analysis and Recognition (SUNY)

- Purdue Sensor and Printer Forensics (PSAPF) Project

- Dr. Mara Merlino at Kentucky State University[43]

Certification

[edit]Due to the nature of certification, there are many bodies that provide this service. Most provide certification to individuals from a particular country or geographic area. In some places, the term accreditation may be used instead of certification. Either way, in the present context, it refers to the assessment of an examiner's competency and qualifications by an independent (third-party) organization of professionals.

Certifying bodies

[edit]Forensic Science Society (UK)

[edit]The Forensic Science Society (UK) provided its members, not limited to UK residents, with the opportunity to obtain a Professional Postgraduate Diploma in forensic disciplines, including Questioned Document Examination, and to use the postnominal 'FSSocDip'.[44] The program was accredited by the University of Strathclyde.

American Board of Forensic Document Examiners

[edit]The American Board of Forensic Document Examiners, Inc. (ABFDE) provides third-party certification for professional forensic document examiners from Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, Australia and New Zealand.[45] The ABFDE is accredited by the Forensic Specialties Accreditation Board.[46]

Board of Forensic Document Examiners

[edit]The US Board of Forensic Document Examiners (BFDE) provides certification of forensic document examiners. The BFDE is accredited by the Forensic Specialties Accreditation Board, which does not have any international affiliations.[46]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Matching Standards Under the Jurisdiction of E30.90 by Status (list)". ASTM International. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "SWGDOC Published Standards". Scientific Working Group for Forensic Document Examination (SWGDOC). Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ "Academy Standards Board Search". AAFS. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Scope of Expertise in Forensic Document Examination" (PDF). Academy Standards Board. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ a b c Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Minimum Training Requirements for Forensic Document Examiners (Withdrawn 2020)". ASTM International. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "SWGDOC Standard for Minimum Training Requirements for Forensic Document Examiners" (PDF). SWGDOC. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ^ In biometrics, this concept is generally referred to as either 'verification' or 'authentication' while the term 'identification' is used to assign an individual to a particular class or group.

- ^ a b c Huber, Roy A.; Headrick, A.M. (April 1999), Handwriting Identification: Facts and Fundamentals, New York: CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-1285-X, archived from the original on 2011-09-28, retrieved 2011-01-19

- ^ Kam et al, A Decade of Writer Identification Proficiency Tests for Forensic Document Examiners, ASQDE, 2003.

- ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Examination of Handwritten Items (Withdrawn 2016)". ASTM International. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "SWGDOC Standard for Examination of Handwritten Items" (PDF). SWGDOC. E01-13. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Academy Standards Board Search" (PDF). AAFS. ASB Forensic Document Examination Consensus Body. ANSI/ASB Standard 70. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ "Best Practice Manual for the Forensic Handwriting Examination (ENFSI-BPM-FHX-01 Edition 04 – September 2022)" (PDF). Best Practice Manuals and Forensic Guidelines. ENFSI. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Scope of Work of Forensic Document Examiners (Withdrawn 2018)". ASTM International. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Terminology Relating to the Examination of Questioned Documents (Withdrawn 2018))". ASTM International. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Terminology for Expressing Conclusions of Forensic Document Examiners (Withdrawn 2017)". ASTM International. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Writing Ink Identification (Withdrawn 2013)". ASTM International. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Examination of Mechanical Checkwriter Impressions (Withdrawn 2017)". ASTM International. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Examination of Dry Seal Impressions (Withdrawn 2017)". ASTM International. Retrieved 26 August 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "E2287-09 Standard Guide for Examination of Fracture Patterns and Paper Fiber Impressions on Single-Strike Film Ribbons and Typed Text (Withdrawn 2018)". ASTM International. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "E2288-09 Standard Guide for Physical Match of Paper Cuts, Tears, and Perforations in Forensic Document Examinations (Withdrawn 2018)". ASTM International. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Examination of Rubber Stamp Impressions (Withdrawn 2017)". ASTM International. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Indentation Examinations (Withdrawn 2012)". ASTM International. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Non-destructive Examination of Paper (Withdrawn 2014)". ASTM International. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)[permanent dead link] - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Examination of Altered Documents (Withdrawn 2013)". ASTM International. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Examination of Documents Produced with Liquid Ink Jet Technology (Withdrawn 2014)". ASTM International. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Examination of Documents Produced with Toner Technology (Withdrawn 2015)". ASTM International. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Subcommittee E30.90 on Executive. "Standard Guide for Examination of Typewritten Items (Withdrawn 2017)". ASTM International. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ ASB Forensic Document Examination Consensus Body. "M". Academy Standards Board. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ ASB Forensic Document Examination Consensus Body (19 August 2022). "Scope of Expertise in Forensic Document Examination". Academy Standards Board. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ ASB Forensic Document Examination Consensus Body (13 September 2021). "Standard for the Examination of Documents for Alterations". Academy Standards Board. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ ASB Forensic Document Examination Consensus Body (13 September 2021). "Standard for Examination of Documents for Indentations". Academy Standards Board. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ ASB Forensic Document Examination Consensus Body. "Standard for Examination of Handwritten Items". Academy Standards Board. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ ASB Forensic Document Examination Consensus Body (13 September 2021). "Standard for Examination of Stamping Devices and Stamp Impressions". Academy Standards Board. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ ASB Forensic Document Examination Consensus Body. "Standard for the Preservation and Examination of Charred Documents". Academy Standards Board. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

- ^ ASB Forensic Document Examination Consensus Body. "Standard for the Preservation and Examination of Liquid Soaked Documents". Academy Standards Board. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ ASB Forensic Document Examination Consensus Body. "Standard for Examination of Mechanical Checkwriter Impressions and Machines". Academy Standards Board. Retrieved 23 February 2024.

- ^ "OSAC Registry". Retrieved 31 March 2024.

The OSAC Registry is a repository of selected published and proposed standards for forensic science. These documents contain minimum requirements, best practices, standard protocols, terminology, or other information to promote valid, reliable, and reproducible forensic results. The standards on this Registry have undergone a technical and quality review process that actively encourages feedback from forensic science practitioners, research scientists, human factors experts, statisticians, legal experts, and the public. Placement on the Registry requires a consensus (as evidenced by 2/3 vote or more) of both the OSAC subcommittee that proposed the inclusion of the standard and the Forensic Science Standards Board. OSAC encourages the forensic science community to implement the published and proposed standards on the Registry to help advance the practice of forensic science.

- ^ The OSAC Registry includes both SDO-published standards and OSAC Proposed Standards.

- ^ "ANSI/ASB Standard 011, Scope of Expertise in Forensic Document Examination. 2022. 1st. Ed". OSAC Registry. 19 August 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "ANSI/ASB Standard 044, Standard for Examination of Documents for Indentations. 2019. 1st. Ed". OSAC Registry. 13 September 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "ASFDE Inc History". Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ^ "Faculty Spotlight: Dr. Mara Merlino". KSU Campus News. Kentucky State University. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ^ "Qualifications and Awards". UK: The Forensic Science Society. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ^ "ABFDE Rules and Procedures Guide" (PDF). General qualifications, Para 1.2. A.B.F.D.E., Inc. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ^ a b "The Forensic Specialties Accreditation Board". FSAB, Inc. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

References

[edit]The literature relating to questioned document examination is very extensive. Publications in English, French, German, and other languages are readily available. The following is a very brief list of English-language textbooks:

- Osborn, A.S. (1929). Questioned Documents, 2nd ed. Albany, New York: Boyd Printing Company. Reprinted, Chicago: Nelson-Hall Co.

- Harrison, W.R. (1958). Suspect Documents: Their Scientific Examination. New York: Praeger.

- Conway, J.V.P. (1959). Evidential Documents. Illinois: Charles C Thomas.

- Hilton, O. (1982). Scientific Examination of Questioned Documents. New York: Elsevier Science Publishing Co.

- Huber R.A. & Headrick A.M. (1999). Handwriting Identification: Facts and Fundamentals. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Ellen, D. (2005). Scientific Examination of Documents: Methods and Techniques, Third Edition. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Morris, R. (2000). Forensic Handwriting Identification: Fundamental Concepts and Principles. Academic Press.

- Levinson, J. (2001). Questioned Documents: A Lawyer's Handbook. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Köller, Norbert; Nissen, Kai; Rieß, Michael; Sadorf, Erwin (2004). Probabilistische Schlussfolgerungen in Schriftgutachten (Probability Conclusions in Expert Opinions on Handwriting) (PDF) (in German and English). Luchterhand, Munchen: BKA. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

External links

[edit] Media related to Questioned document examination at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Questioned document examination at Wikimedia Commons