Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

2001 anthrax attacks

View on Wikipedia

| 2001 anthrax attacks | |

|---|---|

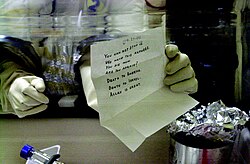

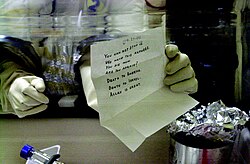

Laboratory technician holding an anthrax-laced letter sent to Senator Patrick Leahy | |

| Location | |

| Date | September 18, 2001 – October 12, 2001 |

| Target | U.S. senators, media figures |

Attack type | Bioterrorism |

| Weapons | Anthrax bacteria |

| Deaths | 5 (Bob Stevens, Thomas Morris Jr., Joseph Curseen, Kathy Nguyen, and Ottilie Lundgren) |

| Injured | 17 |

| Motive | Unknown[1] |

| Accused | Bruce Edwards Ivins, Steven Hatfill (exonerated) |

The 2001 anthrax attacks, also known as Amerithrax (a portmanteau of "America" and "anthrax", from its FBI case name),[1] occurred in the United States over the course of several weeks beginning on September 18, 2001, one week after the September 11 attacks. Letters containing anthrax spores were mailed to several news media offices and to senators Tom Daschle and Patrick Leahy, killing five people and infecting seventeen others. Capitol police officers and staffers working for Senator Russ Feingold were exposed as well. According to the FBI, the ensuing investigation became "one of the largest and most complex in the history of law enforcement".[2] They are the only lethal attacks to have used anthrax outside of warfare.[3]

The FBI and CDC authorized Iowa State University to destroy its anthrax archives in October 2001, which hampered the investigation. Thereafter, a major focus in the early years of the investigation was bioweapons expert Steven Hatfill, who was eventually exonerated. Bruce Edwards Ivins, a scientist at the government's biodefense labs at Fort Detrick in Frederick, Maryland, became a focus around April 4, 2005. On April 11, 2007, Ivins was put under periodic surveillance and an FBI document stated that he was "an extremely sensitive suspect in the 2001 anthrax attacks".[4] On July 29, 2008, Ivins died by suicide with an overdose of acetaminophen (paracetamol).[5]

Federal prosecutors declared Ivins the sole perpetrator on August 6, 2008, based on DNA evidence leading to an anthrax vial in his lab.[6] Two days later, Senator Chuck Grassley and Representative Rush D. Holt Jr. called for hearings into the Department of Justice and FBI's handling of the investigation.[7][8] The FBI formally closed its investigation on February 19, 2010.[9]

In 2008, the FBI requested a review of the scientific methods used in their investigation from the National Academy of Sciences, which released their findings in the 2011 report Review of the Scientific Approaches Used During the FBI's Investigation of the 2001 Anthrax Letters.[10] The report cast doubt on the government's conclusion that Ivins was the perpetrator, finding that the type of anthrax used in the letters was correctly identified as the Ames strain of the bacterium, but that there was insufficient scientific evidence for the FBI's assertion that it originated from Ivins' laboratory.

The FBI responded by saying that the review panel asserted that it would not be possible to reach a definite conclusion based on science alone, and said that a combination of factors led the FBI to conclude that Ivins had been the perpetrator.[11] Some information is still sealed concerning the case and Ivins' mental health.[1]: 8 footnote [12] The government settled lawsuits that were filed by the widow of the first anthrax victim Bob Stevens for $2.5 million with no admission of liability. The settlement was reached solely for the purpose of "avoiding the expenses and risks of further litigations", according to a statement in the agreement.[13]

Context

[edit]The anthrax attacks began a week after the 9/11 attacks, which had caused the destruction of the original World Trade Center in New York City, damage to the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, and the crash of an airliner in an empty field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. The anthrax attacks came in two waves. The first set of letters containing anthrax had a Trenton, New Jersey, postmark dated September 18, 2001. Five letters are believed to have been mailed at this time to ABC News, CBS News, NBC News and the New York Post, all located in New York City, and to the National Enquirer at American Media, Inc., (AMI) in Boca Raton, Florida.[14]

The first known victim of the attacks, Robert Stevens, who worked at the Sun tabloid, also published by AMI, died on October 5, 2001, four days after entering a Florida hospital with an undiagnosed illness that caused him to vomit and be short of breath.[15][16] The presumed letter containing the anthrax which killed Stevens was never found. Only the New York Post and NBC News letters were actually identified;[17] the existence of the other three letters is inferred because individuals at ABC, CBS and AMI became infected with anthrax. Scientists examining the anthrax from the New York Post letter said it was a clumped coarse brown granular material which looked similar to dog food.[18]

Two more anthrax letters, bearing the same Trenton postmark, were dated October 9, three weeks after the first mailing. The letters were addressed to two U.S. senators, Tom Daschle of South Dakota and Patrick Leahy of Vermont. At the time, Daschle was the Senate majority leader and Leahy was head of the Senate Judiciary Committee; both were members of the Democratic Party. The Daschle letter was opened by an aide, Grant Leslie, on October 15, after which the government mail service was immediately shut down. The unopened Leahy letter was discovered in an impounded mailbag on November 16. The Leahy letter had been misdirected to the State Department mail annex in Sterling, Virginia, because a ZIP Code was misread; a postal worker there, David Hose, contracted inhalational anthrax.

More potent than the first anthrax letters, the material in the Senate letters was a highly refined dry powder consisting of about one gram of nearly pure spores. A series of conflicting news reports appeared, some claiming the powders had been "weaponized" with silica. Bioweapons experts who later viewed images of the anthrax used in the attacks saw no indication of "weaponization".[19] Tests at Sandia National Laboratories in early 2002 confirmed that the attack powders were not weaponized.[20][21]

At least 22 people developed anthrax infections, 11 of whom contracted the especially life-threatening inhalational variety. Five died of inhalational anthrax: Stevens; two employees of the Brentwood mail facility in Washington, D.C. (Thomas Morris Jr. and Joseph Curseen),[22] and two whose source of exposure to the bacteria is still unknown: Kathy Nguyen, a Vietnamese immigrant resident of the New York City borough of the Bronx who worked in the city,[23] and the last known victim, Ottilie Lundgren, a 94-year-old widow of a prominent judge from Oxford, Connecticut.[24]

Because it took so long to identify a culprit, the 2001 anthrax attacks have been compared to the Unabomber attacks which took place from 1978 to 1995.[25]

Letters

[edit]Authorities believe that the anthrax letters were mailed from Princeton, New Jersey.[26] Investigators found anthrax spores in a city street mailbox located at 10 Nassau Street near the Princeton University campus. About 600 mailboxes were tested for anthrax which could have been used to mail the letters, and the Nassau Street box was the only one to test positive.

The New York Post and NBC News letters contained the following note:

09–11–01

THIS IS NEXT

TAKE PENACILIN [sic] NOW

DEATH TO AMERICA

DEATH TO ISRAEL

ALLAH IS GREAT

The second note was addressed to Senators Daschle and Leahy and read:

09–11–01

YOU CAN NOT STOP US.

WE HAVE THIS ANTHRAX.

YOU DIE NOW.

ARE YOU AFRAID?

DEATH TO AMERICA.

DEATH TO ISRAEL.

ALLAH IS GREAT.

All of the letters were copies made by a copy machine, and the originals were never found. Each letter was trimmed to a slightly different size. The Senate letter uses punctuation, while the media letter does not. The handwriting on the media letter and envelopes is roughly twice the size of the handwriting on the Senate letter and envelopes. The envelopes addressed to Senators Daschle and Leahy had a fictitious return address:

4th Grade

Greendale School

Franklin Park NJ 08852

Franklin Park, New Jersey, exists, but the ZIP Code 08852 is for nearby Monmouth Junction, New Jersey. There is no Greendale School in Franklin Park or Monmouth Junction, though there is a Greenbrook Elementary School in adjacent South Brunswick Township, New Jersey.

False leads

[edit]The Amerithrax investigation involved many leads which took time to evaluate and resolve. Among them were numerous letters which initially appeared to be related to the anthrax attacks but were never directly linked.

For example, before the New York letters were found, hoax letters mailed from St. Petersburg, Florida, were thought to be the anthrax letters or related to them.[27][28] A letter received at the Microsoft offices in Reno, Nevada, after the discovery of the Daschle letters, gave a false positive in a test for anthrax.[29] Later, because the letter had been sent from Malaysia, Marilyn W. Thompson of The Washington Post connected the letter to Steven Hatfill, whose girlfriend was from Malaysia.[30] The letter merely contained a check and some pornography, and was neither a threat nor a hoax.[31]

A copycat hoax letter containing harmless white powder was opened by reporter Judith Miller in The New York Times newsroom.[32][33]

Also unconnected to the anthrax attacks was a large envelope received at American Media, Inc., in Boca Raton, Florida (which was among the victims of the attacks), in September 2001. It was addressed "Please forward to Jennifer Lopez c/o The Sun", containing a metal cigar tube with a cheap cigar inside, an empty can of chewing tobacco, a small detergent carton, pink powder, a Star of David pendant, and "a handwritten letter to Jennifer Lopez. The writer said how much he loved her and asked her to marry him."[34] Another letter, which mimicked the original anthrax letter to Senator Daschle, was mailed to Daschle from London in November 2001, at a time when Hatfill was in England, not far from London.[35][36][37] Shortly before the discovery of the anthrax letters, someone sent a letter to authorities stating, "Dr. Assaad is a potential biological terrorist."[38] No connection to the anthrax letters was ever found.[39]

During the first years of the FBI's investigation, Don Foster, a professor of English at Vassar College, attempted to connect the anthrax letters and various hoax letters from the same period to Steven Hatfill.[35] Foster's beliefs were published in Vanity Fair and Reader's Digest. Hatfill sued and was later exonerated. The lawsuit was settled out of court.[40]

Anthrax material

[edit]

The letters sent to the media contained a coarse brown material, while the letters sent to the two U.S. Senators contained a fine powder.[41][42] The brown granular anthrax mostly caused cutaneous anthrax infections (9 out of 12 cases), although Kathy Nguyen's case of inhalational anthrax occurred at the same time and in the same general area as two cutaneous cases and several other exposures. The AMI letter which caused inhalation cases in Florida appears to have been mailed at the same time as the other media letters. The fine powder anthrax sent to Daschle and Leahy mostly caused the more dangerous form of infection known as inhalational anthrax (8 out of 10 cases). Postal worker Patrick O'Donnell and accountant Linda Burch contracted cutaneous anthrax from the Senate letters.

All of the material was derived from the same bacterial strain known as the Ames strain.[43] The Ames strain is a common strain isolated from a cow in Texas in 1981. The name "Ames" refers to the town of Ames, Iowa, but was mistakenly attached to this isolate in 1981 because of a mix-up about the mailing label on a package.[44][45] First researched at the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID), at Fort Detrick, Maryland, the Ames strain was subsequently distributed to sixteen bio-research labs within the U.S., as well as three international locations (Canada, Sweden and the United Kingdom).[46]

DNA sequencing of the anthrax collected from Robert Stevens (the first victim) was conducted at The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) beginning in December 2001. Sequencing was finished within a month and the analysis was published in the journal Science in early 2002.[47]

Radiocarbon dating conducted by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in June 2002 established that the anthrax was cultured no more than two years before the mailings.[48]

Mutations

[edit]

Early in 2002, an FBI microbiologist noted that there were variants or mutations in the anthrax cultures grown from powder found in the letters. Scientists at TIGR sequenced the complete genomes from 21 of these isolates during the period from 2002 to 2004. The bioinformatics scientists at TIGR, including Steven Salzberg, Mihai Pop, and Adam M. Phillippy, identified three relatively large changes in some of the isolates, each comprising a region of DNA that had been duplicated or triplicated. The size of these regions ranged from 823 to 2607 base pairs, and all occurred near the same genes. Details of these mutations were published in 2011 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.[49] These changes became the basis of PCR assays used to test other samples to find any that contained the same mutations. The assays were validated over the many years of the investigation, and a repository of Ames samples was also built. From roughly 2003 to 2006, the repository and the screening of the 1,070 Ames samples in that repository were completed.[50]

Controversy over coatings and additives

[edit]On October 24, 2001, USAMRIID scientist Peter Jahrling was summoned to the White House after he reported signs that silicon had been added to the anthrax recovered from the letter addressed to Daschle. Silicon would make the anthrax more capable of penetrating the lungs. Seven years later, Jahrling told the Los Angeles Times on September 17, 2008, "I believe I made an honest mistake,” adding that he had been "overly impressed" by what he thought he saw under the microscope.[51]

Richard Preston's book The Demon in the Freezer[52] provides details of conversations and events at USAMRIID during the period from October 16, 2001, to October 25, 2001. Key scientists described to Preston what they were thinking during that period. When the Daschle spores first arrived at USAMRIID, the key concern was that smallpox viruses might be mixed with the spores. "Jahrling met [John] Ezzell in a hallway and said, in a loud voice, 'Goddamn it, John, we need to know if the powder is laced with smallpox.'" Thus, the initial search was for signs of smallpox viruses. On October 16, USAMRIID scientists began by examining spores that had been "in a milky white liquid" from "a field test done by the FBI's Hazardous Materials Response Unit.” Liquid chemicals were then used to deactivate the spores. When scientists turned up the power on the electron beam of the Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM), "The spores began to ooze." According to Preston,

"Whoa," Jahrling muttered, hunched over the eyepieces. Something was boiling off the spores. "This is clearly bad stuff," he said. This was not your mother's anthrax. The spores had something in them, an additive, perhaps. Could this material have come from a national bioweapons program? From Iraq? Did al-Qaeda have anthrax capability that was this good?

On October 25, 2001, the day after senior officials at the White House were informed that "additives" had been found in the anthrax, USAMRIID scientist Tom Geisbert took a different, irradiated sample of the Daschle anthrax to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) to "find out if the powder contained any metals or elements.” AFIP's energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer reportedly indicated "that there were two extra elements in the spores: silicon and oxygen. Silicon dioxide is glass. The anthrax terrorist or terrorists had put powdered glass, or silica, into the anthrax. The silica was powdered so finely that under Geisbert's electron microscope it had looked like fried-egg gunk dripping off the spores."

The "goop" Peter Jahrling had seen oozing from the spores was not seen when AFIP examined different spores killed with radiation.

The controversy began the day after the White House meeting. The New York Times reported, "Contradicting Some U.S. Officials, 3 Scientists Call Anthrax Powder High-Grade – Two Experts say the anthrax was altered to produce a more deadly weapon,” [53] and The Washington Post reported, "Additive Made Spores Deadlier.” [54] Countless news stories discussed the "additives" for the next eight years, continuing into 2010.[55][56]

Later, the FBI claimed a "lone individual" could have created the anthrax spores for as little as $2,500, using readily available laboratory equipment.[57]

A number of press reports appeared suggesting the Senate anthrax had coatings and additives.[58][59] Newsweek reported the anthrax sent to Senator Leahy had been coated with a chemical compound previously unknown to bioweapons experts.[60] On October 28, 2002, The Washington Post reported "FBI's Theory on Anthrax is Doubted,” [61] suggesting that the senate spores were coated with fumed silica. Two bioweapons experts that were utilized as consultants by the FBI, Kenneth Alibek and Matthew Meselson, were shown electron micrographs of the anthrax from the Daschle letter. In a November 5, 2002 letter to the editors of The Washington Post, they stated that they saw no evidence the anthrax spores had been coated with fumed silica.[19]

In Science magazine, one group of scientists said that the material could have been made by someone knowledgeable with standard laboratory equipment. Another group said it "was a diabolical advance in biological weapons technology.”[62] The article describes "a technique used to anchor silica nanoparticles to the surface of spores" using "polymerized glass.”[62]

An August 2006 article in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, written by Douglas Beecher of the FBI labs in Quantico, Virginia, states "Individuals familiar with the compositions of the powders in the letters have indicated that they were comprised simply of spores purified to different extents."[63] The article also specifically criticizes "a widely circulated misconception" "that the spores were produced using additives and sophisticated engineering supposedly akin to military weapon production.”[63] The harm done by this misconception is described this way: "This idea is usually the basis for implying that the powders were inordinately dangerous compared to spores alone. The persistent credence given to this impression fosters erroneous preconceptions, which may misguide research and preparedness efforts and generally detract from the magnitude of hazards posed by simple spore preparations."[63] Critics of the article complained that it did not provide supporting references.[64][65]

False report of bentonite

[edit]In late October 2001, ABC chief investigative correspondent Brian Ross linked the anthrax sample to Saddam Hussein because of its purportedly containing the unusual additive bentonite. On October 26, Ross said, "sources tell ABCNEWS the anthrax in the tainted letter sent to Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle was laced with bentonite. The potent additive is known to have been used by only one country in producing biochemical weapons—Iraq. ... [I]t is a trademark of Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein's biological weapons program ... The discovery of bentonite came in an urgent series of tests conducted at Fort Detrick, Maryland, and elsewhere." On October 28, Ross said that "despite continued White House denials, four well-placed and separate sources have told ABC News that initial tests on the anthrax by the U.S. Army at Fort Detrick, Maryland, have detected trace amounts of the chemical additives bentonite and silica",[66] a charge that was repeated several times on October 28 and 29.[67]

On October 29, 2001, White House spokesman Scott Stanzel "disputed reports that the anthrax sent to the Senate contained bentonite, an additive that ha[d] been used in Iraqi President Saddam Hussein's biological weapons program.” Stanzel said, "Based on the test results we have, no bentonite has been found.”[68] The same day, Major General John Parker at a White House briefing stated, "We do know that we found silica in the samples. Now, we don't know what that motive would be, or why it would be there, or anything. But there is silica in the samples. And that led us to be absolutely sure that there was no aluminum in the sample, because the combination of a silicate, plus aluminum, is sort of the major ingredients of bentonite."[69] Just over a week later, Homeland Security Advisor Tom Ridge in a White House press conference on November 7, 2001, stated, "The ingredient that we talked about before was silicon."[70] Neither Ross at ABC nor anyone else publicly pursued any further claims about bentonite, despite Ross's original claim that "four well-placed and separate sources" had confirmed its detection.

Dispute over silicon content

[edit]Some of the anthrax spores (65–75%) in the anthrax attack letters contained silicon inside their spore coats. Silicon was even reportedly found inside the natural spore coat of a spore that was still inside the "mother germ,” which was asserted to confirm that the element was not added after the spores were formed and purified, i.e., the spores were not "weaponized.”[20][21]

In 2010, a Japanese study reported, "silicon (Si) is considered to be a "quasiessential" element for most living organisms. However, silicate uptake in bacteria and its physiological functions have remained obscure." The study showed that spores from some species can contain as much as 6.3% dry weight of silicates.[71] "For more than 20 years, significant levels of silicon had been reported in spores of at least some Bacillus species, including those of Bacillus cereus, a close relative of B. anthracis." According to spore expert Peter Setlow, "Since silicate accumulation in other organisms can impart structural rigidity, perhaps silicate plays such a role for spores as well."[72]

The FBI lab concluded that 1.4% of the powder in the Leahy letter was silicon. Stuart Jacobson, a small-particle chemistry expert stated that:

This is a shockingly high proportion [of silicon]. It is a number one would expect from the deliberate weaponization of anthrax, but not from any conceivable accidental contamination.[56]

Scientists at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory conducted experiments in an attempt to determine if the amount of silicon in the growth medium was the controlling factor which caused silicon to accumulate inside a spore's natural coat. The Livermore scientists tried 56 different experiments, adding increasingly high amounts of silicon to the media. All of their results were far below the 1.4% level of the attack anthrax, some as low as .001%. The conclusion was that something other than the level of silicon controlled how much silicon was absorbed by the spores.[56][73]

Richard O. Spertzel, a microbiologist who led the United Nations' biological weapons inspections of Iraq, wrote that the anthrax used could not have come from the lab where Ivins worked.[74] Spertzel said he remained skeptical of the Bureau's argument despite the new evidence presented on August 18, 2008, in an unusual FBI briefing for reporters. He questioned the FBI's claim that the powder was less than military grade, in part because of the presence of high levels of silica. The FBI had been unable to reproduce the attack spores with the high levels of silica. The FBI attributed the presence of high silica levels to "natural variability".[75] This conclusion of the FBI contradicted its statements at an earlier point in the investigation, when the FBI had stated, based on the silicon content, that the anthrax was "weaponized", a step that made the powder more airy and required special scientific know-how.[76]

"If there is that much silicon, it had to have been added," stated Jeffrey Adamovicz, who supervised Ivins' work at Fort Detrick.[56] Adamovicz explained that the silicon in the anthrax attack could have been added via a large fermentor, which Battelle and some other facilities use but "we did not use a fermentor to grow anthrax at USAMRIID ... [and] We did not have the capability to add silicon compounds to anthrax spores." Ivins had neither the skills nor the means to attach silicon to anthrax spores. Spertzel explained that the Fort Detrick facility did not handle anthrax in powdered form. "I don't think there's anyone there who would have the foggiest idea how to do it."[56]

Investigation

[edit]

Authorities traveled to six continents, interviewed over 9,000 people, conducted 67 searches and issued over 6,000 subpoenas. "Hundreds of FBI personnel worked the case at the outset, struggling to discern whether the Sept. 11 al-Qaeda attacks and the anthrax murders were connected before eventually concluding that they were not."[77]

Anthrax archive destroyed

[edit]The FBI and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) both gave permission for Iowa State University to destroy the Iowa anthrax archive and the archive was destroyed on October 10 and 11, 2001.[78]

The FBI and CDC investigation was hampered by the destruction of the large collection of anthrax spores collected over more than seven decades and kept in more than 100 vials at Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa. Many scientists claim that the quick destruction of the anthrax spores collection in Iowa eliminated crucial evidence useful for the investigation. A precise match between the strain of anthrax used in the attacks and a strain in the collection would have offered hints as to when bacteria had been isolated and, perhaps, as to how widely it had been distributed to researchers. Such genetic clues could have given investigators the evidence necessary to identify the perpetrators.[78]

Al-Qaeda and Iraq blamed for attacks

[edit]| Events leading up to the Iraq War |

|---|

|

|

Immediately after the anthrax attacks, White House officials pressured FBI Director Robert Mueller to publicly blame al-Qaeda following the September 11 attacks.[79] During the president's morning intelligence briefings, Mueller was "beaten up" for not producing proof that the killer spores were the handiwork of Osama bin Laden, according to a former aide. "They really wanted to blame somebody in the Middle East," the retired senior FBI official stated.

The FBI knew early on that the anthrax used was of a consistency requiring sophisticated equipment and was unlikely to have been produced in "some cave". At the same time, President Bush and Vice President Cheney in public statements speculated about the possibility of a link between the anthrax attacks and al-Qaeda.[80] The Guardian reported in early October that American scientists had implicated Iraq as the source of the anthrax,[81] and the next day The Wall Street Journal editorialized that al-Qaeda perpetrated the mailings, with Iraq the source of the anthrax.[82] A few days later, John McCain suggested on the Late Show with David Letterman that the anthrax may have come from Iraq,[83] and the next week ABC News did a series of reports stating that three or four (depending on the report) sources had identified bentonite as an ingredient in the anthrax preparations, implicating Iraq.[66][67][84]

Statements by the White House[68] and public officials[69] quickly stated that there was no bentonite in the attack anthrax. "No tests ever found or even suggested the presence of bentonite. The claim was just concocted from the start. It just never happened."[85] Nonetheless, a few journalists repeated ABC's bentonite report for several years,[86] even after the invasion of Iraq proved there was no involvement. In an interview with Hamid Mir, Osama bin Laden denied any knowledge of the Anthrax attacks.[87]

"Person of interest"

[edit]Barbara Hatch Rosenberg, a molecular biologist at the State University of New York at Purchase and chairwoman of a biological weapons panel at the Federation of American Scientists, and others began claiming that the attack might be the work of a "rogue CIA agent" in October 2001, as soon as it became known that the Ames strain of anthrax had been used in the attacks, and she told the FBI the name of the "most likely" person.[88] On November 21, 2001, she made similar statements to the Biological and Toxic Weapons convention in Geneva.[89] In December 2001, she published "A Compilation of Evidence and Comments on the Source of the Mailed Anthrax" via the web site of the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), claiming that the attacks were "perpetrated with the unwitting assistance of a sophisticated government program".[90] She discussed the case with reporters from The New York Times.[91] In Rosenberg's assessment, the suspect(s) must have had "the right skills, experience with anthrax, up-to-date anthrax vaccination, forensic training and access to USAMRIID and its biological agents."[88]

On January 4, 2002, Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times published a column titled "Profile of a Killer"[92] stating "I think I know who sent out the anthrax last fall." For months, Rosenberg gave speeches and stated her beliefs to many reporters from around the world. She posted "Analysis of the Anthrax Attacks" to the FAS web site on January 17, 2002. On February 5, 2002, she published "Is the FBI Dragging Its Feet?"[93] In response, the FBI stated, "There is no prime suspect in this case at this time".[94] The Washington Post reported, "FBI officials over the last week have flatly discounted Dr. Rosenberg's claims".[95] On June 13, 2002, Rosenberg posted "The Anthrax Case: What the FBI Knows" to the FAS site.[96] On June 18, 2002, she presented her theories to Senate staffers working for Senators Daschle and Leahy.[97]

On June 25, the FBI publicly searched Steven Hatfill's apartment, and he became a household name. "The FBI also pointed out that Hatfill had agreed to the search and is not considered a suspect."[98] American Prospect and Salon.com reported, "Hatfill is not a suspect in the anthrax case, the FBI says."[99] On August 3, 2002, Rosenberg told the media that the FBI asked her if "a team of government scientists could be trying to frame Steven J. Hatfill".[100] In August 2002, Attorney General John Ashcroft labeled Hatfill a "person of interest" in a press conference, though no charges were brought against him. Hatfill is a virologist, and he vehemently denied that he had anything to do with the anthrax mailings and sued the FBI, the Justice Department, Ashcroft, Alberto Gonzales, and others for violating his constitutional rights and for violating the Privacy Act. On June 27, 2008, the Department of Justice announced that it would settle Hatfill's case for $5.8 million.[101]

Hatfill also sued The New York Times and its columnist Kristof, as well as Donald Foster, Vanity Fair, Reader's Digest, and Vassar College for defamation. The case against The New York Times was initially dismissed,[102] but it was reinstated on appeal. The dismissal was upheld by the appeals court on July 14, 2008, on the basis that Hatfill was a public figure and malice had not been proven.[103] The Supreme Court rejected an appeal on December 15, 2008.[104] Hatfill's lawsuits against Vanity Fair and Reader's Digest were settled out of court in February 2007, but no details were made public. The statement released by Hatfill's lawyers[40] said, "Dr. Hatfill's lawsuit has now been resolved to the mutual satisfaction of all the parties".

Bruce Edwards Ivins

[edit]

Bruce E. Ivins had worked for 18 years at the government's bio defense labs at Fort Detrick as a biodefense researcher. The Associated Press reported on August 1, 2008, that he had apparently committed suicide at the age of 62. It was widely reported that the FBI was about to press charges against him, but the evidence was largely circumstantial and the grand jury in Washington reported that it was not ready to issue an indictment.[105] Rush D. Holt Jr. represented the district where the anthrax letters were mailed, and he said that circumstantial evidence was not enough and asked FBI director Robert S. Mueller to appear before Congress to provide an account of the investigation.[106] Ivins' death left two unanswered questions. Scientists familiar with germ warfare said that there was no evidence that he had the skills to turn anthrax into an inhalable powder. Alan Zelicoff aided the FBI investigation, and he stated: "I don't think a vaccine specialist could do it... This is aerosol physics, not biology".[107]

W. Russell Byrne worked in the bacteriology division of the Fort Detrick research facility. He said that Ivins was "hounded" by FBI agents who raided his home twice, and he was hospitalized for depression during that time. According to Byrne and local police, Ivins was removed from his workplace out of fears that he might harm himself or others. "I think he was just psychologically exhausted by the whole process," Byrne said. "There are people who you just know are ticking bombs. He was not one of them."[108]

On August 6, 2008, federal prosecutors declared Ivins the sole perpetrator of the crime when US Attorney Jeffrey A. Taylor laid out the case to the public. "The genetically unique parent material of the anthrax spores... was created and solely maintained by Dr. Ivins." But other experts disagreed, including biological warfare and anthrax expert Meryl Nass, who stated: "Let me reiterate: no matter how good the microbial forensics may be, they can only, at best, link the anthrax to a particular strain and lab. They cannot link it to any individual." At least 10 scientists had regular access to the laboratory and its anthrax stock, and possibly quite a few more, counting visitors from other institutions and workers at laboratories in Ohio and New Mexico that had received anthrax samples from the flask.[109] The FBI later claimed to have identified 419 people at Fort Detrick and other locations who had access to the lab where flask RMR-1029 was stored, or who had received samples from flask RMR-1029.[110]

Mental health issues

[edit]Ivins told a mental health counselor more than a year before the anthrax attacks that he was interested in a young woman who lived out of town and that he had "mixed poison" which he took with him when he went to watch her play in a soccer match. "If she lost, he was going to poison her," said the counselor, who treated Ivins at a Frederick clinic four or five times in mid-2000. She said that Ivins emphasized that he was a skillful scientist who "knew how to do things without people finding out". The counselor was so alarmed by his emotionless description of a specific, homicidal plan that she immediately alerted the head of her clinic and a psychiatrist who had treated Ivins, as well as the Frederick Police Department. She said that the police told her that nothing could be done because she did not have the woman's address or last name.[111]

In 2008, Ivins told a different therapist that he planned to kill his co-workers and "go out in a blaze of glory". That therapist stated in an application for a restraining order that Ivins had a "history dating to his graduate days of homicidal threats, actions, plans, threats and actions towards therapists". Dr. David Irwin, his psychiatrist, called him "homicidal, sociopathic with clear intentions."[112]

Evidence of consciousness of guilt

[edit]

According to the report on the Amerithrax investigation published by the Department of Justice, Ivins engaged in actions and made statements that indicated a consciousness of guilt. He took environmental samples in his laboratory without authorization and decontaminated areas in which he had worked without reporting his activities. He also threw away a book about secret codes, which described methods similar to those used in the anthrax letters. Ivins threatened other scientists, made equivocal statements about his possible involvement in a conversation with an acquaintance, and put together outlandish theories in an effort to shift the blame for the anthrax mailings to people close to him.[1]: 9

The FBI said that Ivins' justifications for his actions after the environmental sampling, as well as his explanations for a subsequent sampling, contradicted his explanation for the motives for the sampling.[113]

According to the Department of Justice, flask RMR-1029, which was created and controlled by Ivins, was used to create "the murder weapon".[46][114][115][116]

In 2002, researchers did not believe it was possible to distinguish between anthrax variants.[117] In January 2002, Ivins suggested that DNA sequencing should show differences in the genetics of anthrax mutations which would allow the source to be identified. Despite researchers advising the FBI that this may not have been possible, Ivins tutored agents on how to recognize them. Considered cutting edge at the time, the technique is now commonplace.[117]

In February 2002, Ivins volunteered to provide samples from several variants of the Ames strain in order to compare their morphs. He submitted two test tube "slants" each from four samples of the Ames strain in his collection. Two of the slants were from flask RMR-1029. Although the slants from flask RMR-1029 were later reported to be a positive match, all eight slants were reportedly in the wrong type of test tube and would therefore not be usable as evidence in court. On March 29, 2002, Ivins' boss instructed Ivins and others in suites B3 and B4 on how to properly prepare slants for the FBI Repository. The subpoena also included instructions on the proper way to prepare slants. When Ivins was told that his February samples did not meet FBIR requirements, he prepared eight new slants. The two new slants prepared from flask RMR-1029 submitted in April by Ivins did not contain the mutations that were later determined to be in flask RMR-1029.[118][119]

It was reported that in April 2004, Henry Heine found a test tube in the lab containing anthrax and contacted Ivins.[117] In an email sent in reply, Ivins reportedly told him it was probably RMR-1029 and for Heine to forward a sample to the FBI.[117] Doubts regarding the reliability of the FBI tests were later raised when the FBI tested Heine's sample and a further one from Heine's test tube: one tested negative and one positive.[117]

A DOJ summary report of February 19, 2010, said that "the evidence suggested that Dr. Ivins obstructed the investigation either by providing a submission which was not in compliance with the subpoena, or worse, that he deliberately submitted a false sample."[1]: 79 Records released under the Freedom of Information Act in 2011 show that Ivins provided four sets of samples from 2002 to 2004, twice the number the FBI reported. Three of the four sets tested positive for the morphs.[117]

The FBI said that "At a group therapy session on July 9, 2008, Dr. Ivins was particularly upset. He revealed to the counselor and psychologist leading the group, and other members of the group, that he was a suspect in the anthrax investigation and that he was angry at the investigators, the government, and the system in general. He said he was not going to face the death penalty, but instead had a plan to 'take out' co-workers and other individuals who had wronged him. He noted that it was possible, with a plan, to commit murder and not make a mess. He stated that he had a bullet-proof vest, and a list of co-workers who had wronged him, and said that he was going to obtain a Glock firearm from his son within the next day, because federal agents were watching him and he could not obtain a weapon on his own. He added that he was going to 'go out in a blaze of glory.'"[1]: 50

While in a mental hospital, Ivins allegedly made menacing phone calls[120] to his social worker Jean Duley on July 11 and 12.

Alleged hidden texts

[edit]In the letters sent to the media, the characters 'A' and 'T' were sometimes emboldened or highlighted by tracing over, according to the FBI suggesting that the letters contained a hidden code.[1]: 58 [9][121][122][123][124]

Some believe the letters to the New York Post[125] and Tom Brokaw[126] contained a "hidden message" in such highlighted characters. Below is the media text with the highlighted As and Ts:

- 09-11-01

- THIS IS NEXT

- TAKE PENACILIN [sic] NOW

- DEATH TO AMERICA

- DEATH TO ISRAEL

- ALLAH IS GREAT

According to the FBI, Summary Report issued on February 19, 2010, following the search of Ivins' home, cars, and office on November 1, 2007, investigators began examining his trash.[1]: 64 A week later, just after 1:00 a.m. on the morning of November 8, the FBI stated that Ivins was observed throwing away "a copy of a book entitled Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, published by Douglas Hofstadter in 1979" and "a 1992 issue of American Scientist Journal which contained an article entitled 'The Linguistics of DNA,' and discussed, among other things, codons and hidden messages".[1]: 61

The book Gödel, Escher, Bach contains a lengthy description of the encoding/decoding procedures, including an illustration of hiding a message within a message by emboldening certain characters.[127] According to the FBI Summary Report, "[w]hen they lifted out just the bolded letters, investigators got TTT AAT TAT – an apparent hidden message". The 3-letter groups are codons, "meaning that each sequence of three nucleic acids will code for a specific amino acid".[1]: 59

- TTT = Phenylalanine (single-letter designator F)

- AAT = Asparagine (single-letter designator N)

- TAT = Tyrosine (single-letter designator Y)

The FBI Summary Report proceeds to say: "From this analysis, two possible hidden meanings emerged: (1) 'FNY' – a verbal assault on New York, and (2) PAT – the nickname of [Dr. Ivins'] Former Colleague #2." Ivins was known to have a dislike for New York City, and four of the media letters had been sent to New York.[1]: 60 The report states that it "was obviously impossible for the Task Force to determine with certainty that either of these two translations was correct", however, "the key point to the investigative analysis is that there is a hidden message, not so much what that message is".[1]: 60 According to the FBI, Ivins showed a fascination with codes and also had an interest in secrets and hidden messages,[1]: 60 ff and was familiar with biochemical codons.[1]: 59 ff

Ivins' "non-denial" denials

[edit]Experts have suggested that the anthrax mailings included a number of indications that the mailer was trying to avoid harming anyone with his warning letters.[35][90]

Examples:

- None of the intended recipients of the letters were infected.

- The seams on the backs of the envelopes were taped over as if to make certain the powders could not escape through open seams.[128]

- The letters were folded with the "pharmaceutical fold", which was used for centuries to safely contain and transport doses of powdered medicines (and currently to safely hold trace evidence).[citation needed]

- The media letters provided "medical advice": "TAKE PENACILIN [sic] NOW."

- The Senate letters informed the recipient that the powder was anthrax: "WE HAVE THIS ANTHRAX."

- At the time of the mailings, it was generally believed that such powders could not escape from a sealed envelope except through the two open corners where a letter opener is inserted, which had been taped shut.[129]

In June 2008, Ivins was involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital. The FBI stated that during a June 5 group therapy session there, Ivins had a conversation with an unnamed witness, during which he made a series of statements about the anthrax mailings that the FBI said could best be characterized as "non-denial denials".[1]: 70–71 When asked about the anthrax attacks and whether he could have had anything to do with them, the FBI said that Ivins admitted he suffered from loss of memory, stating that he would wake up dressed and wonder if he had gone out during the night. Some of his responses allegedly included the following selected quotes:

- "I can tell you I don't have it in my heart to kill anybody."

- "I do not have any recollection of ever have doing anything like that. As a matter of fact, I don't have no clue how to, how to make a bio-weapon and I don't want to know."

- "I can tell you, I am not a killer at heart."

- "If I found out I was involved in some way, and, and ..."

- "I don't think of myself as a vicious, a, a nasty evil person."

- "I don't like to hurt people, accidentally, in, in any way. And [several scientists at USAMRIID] wouldn't do that. And I, in my right mind wouldn't do it [laughs] ... But it's still, but I still feel responsibility because [the RMR-1029 flask containing the anthrax spores] wasn't locked up at the time ..."

In an interview with a confidential human resource (CHR) which took place on January 8, 2008, the FBI said that the CHR told FBI agents that since Ivins' last interview with the FBI (on November 1, 2007), Ivins had "on occasion spontaneously declared at work, 'I could never intentionally kill or hurt someone'".[130]

Doubts about FBI conclusions

[edit]After the FBI announced that Ivins acted alone, many people with a broad range of political views, some of whom were colleagues of Ivins, expressed doubts.[131] Reasons cited for these doubts include that Ivins was only one of 100 people who could have worked with the vial used in the attacks and that the FBI could not place him near the New Jersey mailbox from which the anthrax was mailed.[131][132] The FBI's own genetic consultant, Claire Fraser-Ligget, stated that the failure to find any anthrax spores in Ivins' house, vehicle or on any of his belongings seriously undermined the case.[119] Noting unanswered questions about the FBI's scientific tests and lack of peer review, Jeffrey Adamovicz, one of Ivins' supervisors in USAMRIID's bacteriology division, stated, "I'd say the vast majority of people [at Fort Detrick] think he had nothing to do with it."[133] More than 200 colleagues attended his memorial service following his death.[134]

Alternative theories proposed include FBI incompetence, that Syria or Iraq directed the attacks, or that similar to some 9/11 conspiracy theories the US government knew in advance that the attacks would occur.[131] The Washington Post called for an independent investigation in the case saying that reporters and scientists were poking holes in the case.[135]

On September 17, 2008, Senator Patrick Leahy told FBI Director Robert Mueller during testimony before the Judiciary Committee which Leahy chairs, that he did not believe Army scientist Bruce Ivins acted alone in the 2001 anthrax attacks, stating:

I believe there are others involved, either as accessories before or accessories after the fact. I believe that there are others out there. I believe there are others who could be charged with murder.[136]

In 2011 Leahy maintained to the Washington Post that the attacks had certainly involved other "people who at the very least were accessories after the fact," and also found it "strange that one person would target such an odd collection of media and political figures".[137]

Tom Daschle, the other Democratic senator targeted, believes Ivins was the sole culprit.[138]

Although the FBI matched the genetic origin of the attack spores to the spores in Ivins' flask RMR-1029, the spores within that flask did not have the same silicon chemical "fingerprint" as the spores in the attack letters. The implication is that spores taken out of flask RMR-1029 had been used to grow new spores for the mailings.[139]

On April 22, 2010, the U.S. National Research Council, the operating arm of the National Academy of Sciences, convened a review committee that heard testimony from Henry Heine, a microbiologist who was formerly employed at the Army's biodefense laboratory in Maryland where Ivins had worked. Heine told the panel that it was impossible that the deadly spores had been produced undetected in Ivins' laboratory, as maintained by the FBI. He testified that at least a year of intensive work would have been required using the equipment at the army lab to produce the quantity of spores contained in the letters and that such an intensive effort could not have escaped the attention of colleagues.

Heine also told the panel that lab technicians who worked closely with Ivins have told him they saw no such work. He stated further that biological containment measures where Ivins worked were inadequate to prevent Anthrax spores from floating out of the laboratory into animal cages and offices. "You'd have had dead animals or dead people," Heine said.[140] According to Science Magazine,[141] "Heine caveated his remarks by saying that he himself had no experience making anthrax stocks." Science magazine provides additional comments by Adam Driks of Loyola who stated that the amount of anthrax in the letters could be made in "a number of days". Emails by Ivins state, "We can presently make 1 X 10^12 [one trillion] spores per week."[142] And The New York Times reported on May 7, 2002, that the Leahy letter contained .871 grams of anthrax powder [equivalent to 871 billion spores][143]

In a technical article to be published in the Journal of Bioterrorism & Biodefense in 2011, three scientists argued that the preparation of the spores did require a high level of sophistication, contrary to the position taken by federal authorities that the material would have been unsophisticated. The paper is largely based on the high level of tin detected in tests of the mailed anthrax, and the tin may have been used to encapsulate the spores, which required processing not possible in laboratories to which Ivins had access. According to the scientific article, this raises the possibility that Ivins was not the perpetrator or did not act alone.

Earlier in the investigation, the FBI had named tin as a substance "of interest" but the final report makes no mention of it and fails to address the high tin content. The chairwoman of the National Academy of Sciences panel that reviewed the FBI's scientific work and the director of a separate review by the Government Accountability Office said that the issues raised by the paper should be addressed. Other scientists, such as Johnathan L. Kiel, a retired Air Force scientist who worked on anthrax for many years, did not agree with the authors' assessments — saying that the tin might be a random contaminant rather than a clue to complex processing.[144] Kiel said that tin might simply be picked up by the spores as a result of the use of metal lab containers, although he had not tested that idea.[144]

In 2011, the chief of the Bacteriology Division at the Army laboratory, Patricia Worsham, said it lacked the facilities in 2001 to make the kind of spores in the letters. In 2011, the government conceded that the equipment required was not available in the lab, calling into question a key pillar of the FBI's case, that Ivins had produced the anthrax in his lab. According to Worsham, the lab's equipment for drying spores, a machine the size of a refrigerator, was not in containment so that it would be expected that non-immunized personnel in that area would have become ill. Colleagues of Ivins at the lab have asserted that he could not have grown the quantity of anthrax used in the letters without their noticing it.[145]

A spokesman for the Justice Department said in 2011 that the investigators continue to believe that Ivins acted alone.[144]

Congressional oversight

[edit]Congressman Rush Holt, whose district in New Jersey includes a mailbox from which anthrax letters are believed to have been mailed, called for an investigation of the anthrax attacks by Congress or by an independent commission he proposed in a bill entitled the Anthrax Attacks Investigation Act (H.R. 1248).[146] Other members of Congress have also called for an independent investigation.[147]

An official of the U.S. administration said in March 2010 that President Barack Obama probably would veto legislation authorizing the next budget for U.S. intelligence agencies if it called for a new investigation into the 2001 anthrax attacks, as such an investigation "would undermine public confidence" in an FBI probe.[148] In a letter to congressional leaders, Peter Orszag, the director of the Office of Management and Budget at the time, wrote that an investigation would be "duplicative", and expressed concern about the appearance and precedent involved when Congress commissions an agency Inspector General to replicate a criminal investigation, but did not list the anthrax investigation as an issue that was serious enough to advise the President to veto the entire bill.[149]

National Academy of Sciences review

[edit]In what appears to have been a response to lingering skepticism, on September 16, 2008, the FBI asked the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) to conduct an independent review of the scientific evidence that led the agency to implicate U.S. Army researcher Bruce Ivins in the anthrax letter attacks of 2001.[10] However, despite taking this action, Director Mueller said that the scientific methods applied in the investigation had already been vetted by the research community through the involvement of several dozen nonagency scientists.[10]

The NAS review officially got underway on April 24, 2009.[140] While the scope of the project included the consideration of facts and data surrounding the investigation of the 2001 Bacillus anthracis mailings, as well as a review of the principles and methods used by the FBI, the NAS committee was not given the task to "undertake an assessment of the probative value of the scientific evidence in any specific component of the investigation, prosecution, or civil litigation", nor to offer any view on the guilt or innocence of any of the involved people.[150]

In mid-2009, the NAS committee held public sessions, in which presentations were made by scientists, including scientists from the FBI laboratories.[151][152][153] In September 2009, scientists, including Paul Keim of Northern Arizona University, Joseph Michael of Sandia National Laboratory and Peter Weber of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, presented their findings.[154][155] In one of the presentations, scientists reported that they did not find any silica particles on the outside of the spores (i.e., there was no "weaponization"[citation needed]), and that only some of the spores in the anthrax letters contained silicon inside their spore coats. One of the spores was still inside the "mother germ", yet it already had silicon inside its spore coat.[20][156]

In October 2010, the FBI submitted materials to NAS that it had not previously provided. Included in the new materials were results of analyses performed on environmental samples collected from an overseas site. Those analyses yielded evidence of the Ames strain in some samples. NAS recommended a review of those investigations.[157]

The NAS committee released its report on February 15, 2011, concluding that it was "impossible to reach any definitive conclusion about the origins of the anthrax in the letters, based solely on the available scientific evidence".[157] The report also challenged the FBI and U.S. Justice Department's conclusion that a single-spore batch of anthrax maintained by Ivins at his laboratory at Fort Detrick in Maryland was the parent material for the spores in the anthrax letters.[157][158]

Government Accountability Office

[edit]A study by the United States Government Accountability Office found shortcomings in the FBI's testing methods. In particular, according to the GAO analysis, the FBI's testing method lacked an understanding of the conditions that enable genetic mutations, which is necessary to differentiate between anthrax samples; the FBI failed to institute rigorous controls over the anthrax sampling procedures; and the FBI failed to include measures of uncertainty, which is important for accurate statistical interpretation of testing results.[159]

Aftermath

[edit]

Contamination and cleanup

[edit]Dozens of buildings were contaminated with anthrax as a result of the mailings. New York-based Bio Recovery Corporation and Ohio-based Bio-Recovery Services of America were placed in charge of the cleanup and decontamination of buildings in New York City, including ABC Headquarters and a midtown Manhattan building that was part of the Rockefeller Center and was home to the New York Post and Fox News.[160] Bio Recovery provided the labor and equipment, such as HEPA filtered negative pressure air scrubbers, HEPA vacuums, respirators, cyclone foggers, and decontamination foam licensed by the Sandia National Laboratories. Ninety-three bags of anthrax-contaminated mail were removed from the New York Post alone.[161]

The decontamination of the Brentwood postal facility took 26 months and cost $130 million. The Hamilton, New Jersey, postal facility[162] remained closed until March 2005; its cleanup cost $65 million.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency led the collaborative effort to clean up the Hart Senate Office Building, where Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle's office was located, as well as the Ford Office Building and several other locations around the capitol.[163] It used $27 million of its funds for its Superfund program on the Capitol Hill anthrax cleanup.[164] One FBI document said the total damage exceeded $1 billion.[165]

Preparedness and research

[edit]The anthrax attacks, as well as the September 11, 2001 attacks, spurred significant increases in U.S. government funding for biological warfare research and preparedness. For example, biowarfare-related funding at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) increased by $1.5 billion in 2003. In 2004, Congress passed the Project Bioshield Act, which provides $5.6 billion over ten years for the purchase of new vaccines and drugs.[166] These included the monoclonal antibody raxibacumab, which treats anthrax as well as an Anthrax Vaccine Adsorbed, both of which are stockpiled by the US government.[167]

Immediately after 9/11, well before the mailing of any of the letters involved in the anthrax attacks, the White House began distributing ciprofloxacin, the only drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of inhalational anthrax,[168] to senior staffers.[169][170]

Ciprofloxacin manufacturer Bayer agreed to provide the United States with 100,000 doses for $.95 per dose, a cut in the price from $1.74.[171] The Canadian government had previously overridden the Bayer patent,[172] and the US was threatening the same measure if Bayer did not agree to negotiate the price.[173] Shortly afterward, it was recommended that doxycycline was a more appropriate drug to treat anthrax exposure.[171] A widened use of the broad-spectrum antibiotic ciprofloxacin had also raised serious concerns amongst scientists about the creation and increased spread of drug-resistant bacteria strains.[171] Numerous corporations offered to supply drugs free of charge, contingent on the Food and Drug Administration approving their products for anthrax treatment. They included Bristol Myers Squibb (gatifloxacin), Johnson and Johnson (levofloxacin) and GlaxoSmithKline (two drugs). Eli Lilly and Pfizer also offered to provide drugs at cost.[171]

U.S. mail crackdowns

[edit]The attack led to the widespread confiscation and curtailment of US Mail, especially to US media companies: "checks, bills, letters, and packages simply stopped arriving. For many people and businesses that had resisted the cultural shift to e-mail, this was the moment that pushed them online."[79]

Policy

[edit]After the 9/11 attacks and the subsequent anthrax mailings, lawmakers were pressed for legislation to combat further terrorist acts. Under heavy pressure from then Attorney General John D. Ashcroft, a bipartisan compromise in the House Judiciary Committee allowed legislation for the Patriot Act to move forward for full consideration later that month.[174][175]

A theory that Iraq was behind the attacks, based upon purported evidence that the powder was weaponized and some reports of alleged meetings between 9/11 conspirators and Iraqi officials, may have contributed to the hysteria which ultimately enabled the 2003 Invasion of Iraq.[176]

Adverse health effects

[edit]Years after the attack, several anthrax victims reported lingering health problems including fatigue, shortness of breath and memory loss.[177]

A 2004 study proposed that the total number of people harmed by the anthrax attacks of 2001 should be raised to 68.[178]

A postal inspector, William Paliscak, became severely ill and disabled after removing an anthrax-contaminated air filter from the Brentwood mail facility on October 19, 2001. Although his doctors, Tyler Cymet and Gary Kerkvliet, believe that the illness was caused by anthrax exposure, blood tests did not find anthrax bacteria or antibodies, and therefore the CDC does not recognize it as a case of inhalational anthrax.[179]

Media

[edit]Television

[edit]The case was referenced on season 4, episode 24 of Criminal Minds.[citation needed]

The second season of the National Geographic TV series The Hot Zone focused on the attack.[180]

Season 12, episode 13 of Unsolved Mysteries prominently featured the anthrax attacks in detail.[citation needed]

Dan Krauss's The Anthrax Attacks: In the Shadow of 9/11 from Netflix and the BBC takes a "quasi-documentary" approach to the investigation. First streamed on September 8, 2022.[181][182]

Season 8, episode 3 of How It Really Happened covers the timeline of the attacks and investigation; it was first streamed in June 2024.[citation needed]

Season 1, episode 13 of House, M.D., titled "Cursed" (March 2005), references Amerithrax. When Dr. House diagnoses a 12-year-old child with anthrax, he jokingly mentions Saddam Hussein, although Saddam had no involvement with 9/11 or Amerithrax. Shortly after, the patient's father, an U.S. Air Force test pilot, sarcastically mentions terrorism.

Season 2, episode 23, Law and Order: Criminal Intent, in a straight out of the headlines type story, in this case involving a scientist falsely accused of an anthrax attack who appears to commit suicide because of the accusations. https://www.rottentomatoes.com/tv/law-and-order-criminal-intent/s02/e23

See also

[edit]- Anthrax hoax

- 1984 Rajneeshee bioterror attack – first widely recognized instance of bioterror in the United States

- 2003 ricin letters

- April 2013 ricin letters

- Austin serial bombings

- Anthrax War, 2009 documentary

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Domestic terrorism in the United States

- Health crisis

- List of journalists killed in the United States

- List of unsolved murders

- October 2018 United States mail bombing attempts

- Statement on Chemical and Biological Defense Policies and Programs

- Timeline of violent incidents at the United States Capitol

- United States Postal Service Irradiated mail

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Amerithrax Investigative Summary" (PDF). United States Department of Justice. Federal Bureau of Investigation. February 19, 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 15, 2014. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- ^ Amerithrax or Anthrax Investigation Archived November 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation.

- ^ Pita, René; Gunaratna, Rohan (January 2, 2010). "Anthrax as a Biological Weapon: From World War I to the Amerithrax Investigation". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 23 (1): 61–103. doi:10.1080/08850600903143304. ISSN 0885-0607.

- ^ FBI Amerithrax Documents (PDF) (published December 9, 2008), April 1, 2005, p. 67, archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2011

- ^ "Ivins case reignites debate on anthrax". Los Angeles Times. August 3, 2008. Archived from the original on May 12, 2009. Retrieved April 5, 2009.

- ^ "U.S. officials declare researcher is anthrax killer". CNN. August 6, 2008. Archived from the original on August 8, 2008. Retrieved August 7, 2008.

- ^ Meyer, Josh (August 8, 2008). "Anthrax investigation should be investigated, congressmen say". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 12, 2008. Retrieved August 8, 2008.

- ^ Cole, Leonard A. (2009). The Anthrax Letters: A Bioterrorism Expert Investigates the Attacks That Shocked America—Case Closed?. SkyhorsePublishing. ISBN 978-1-60239-715-6. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Shane, Scott (February 19, 2010). "F.B.I., Laying Out Evidence, Closes Anthrax Letters Case". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 25, 2010. Retrieved February 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c Review of the Scientific Approaches Used During the FBI's Investigation of the 2001 Anthrax Letters. National Academies Press. 2011. doi:10.17226/13098. ISBN 978-0-309-18719-0. PMID 24983068.

- ^ Sheridan, Kerry (February 15, 2011). "Science review casts doubt on 2001 anthrax case". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on April 23, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ^ Shane, Scott (February 16, 2011). "Expert Panel Is Critical of F.B.I. Work in Investigating Anthrax Letters". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 17, 2011. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

- ^ "Government Settles Anthrax Suit for $2.5 million". Frontline. pbs.org. November 29, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Andrew C. Revkin and Dana Canedy, "Anthrax Pervades Florida Site, and Experts See Likeness to That Sent to Senators" Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, December 5, 2001

- ^ "Chronology of 2001 anthrax events". Sun-Sentinel. December 24, 2012. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- ^ "An Anthrax Widow May Sue U.S. Woman Whose Husband Died In Florida Is Angry At Army Lab's Possible Role As Bacteria's Source". Sun Sentinel. October 9, 2002. Archived from the original on September 20, 2012. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- ^ "My anthrax survivor's story – NBC News employee speaks out for the first time on her ordeal". NBC News. September 13, 2006. Archived from the original on October 21, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- ^ Orin, Deborah (October 26, 2001). "Anthrax Spreads as Probe Widens". New York Post. Archived from the original on December 27, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Frerichs, Ralph R. (November 5, 2002). "Anthrax Under The Microscope". ph.ucla.edu. University of California, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Sandia aids FBI in investigation of anthrax letters". YouTube. November 19, 2008. Archived from the original on November 1, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ a b "J. Michael, September 25, 2009 NAS presentation" (MP3 audio). nationalacademies.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ O'Keefe, Ed (October 21, 2011). "Postal workers mark 10 years since anthrax attacks". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ Thomas, Evan (November 11, 2001). "Who Killed Kathy Nguyen?". Newsweek. Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ Altimari, Dave (April 14, 2014). "Oxford Woman, 94, An Unlikely Victim Of Anthrax Attacks". Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on September 17, 2018. Retrieved September 16, 2018.

- ^ Lengel, Allan (September 16, 2005). "Little Progress In FBI Probe of Anthrax Attacks". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 16, 2007. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- ^ "Anthrax: a Political Whodunit". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- ^ Miller, Judith (October 14, 2001). "Fear Hits Newsroom in a Cloud of Powder". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 2, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ "Tampabay: Brokaw's aide tests positive". St Petersburg Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ Powell, Michael; Blum, Justin (October 14, 2001). "Anthrax confirmed at Microsoft in Reno; 5 more cases in Florida". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on October 16, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ Frerichs, Ralph R. "Md. Pond Drained for Clues in Anthrax Probe". ph.ucla.edu. University of California, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ Nieves, Evelyn (October 15, 2001). "A Nation Challenged: Nevada; Final Tests Are Negative For 4 Workers In Reno Office". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ David Barstow (Oct. 13, 2001), "A NATION CHALLENGED: THE INCIDENTS; Anthrax Found in NBC News Aide" Archived October 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times

- ^ Judith Miller (Oct. 14, 2001), "A NATION CHALLENGED: THE LETTER; Fear Hits Newsroom In a Cloud of Powder" Archived October 27, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times

- ^ The National Enquirer, October 31, 2001.

- ^ a b c Frerichs, Ralph R. "The Message in the Anthrax". ph.ucla.edu. University of California, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ "FBI: Letter in Daschle's office a hoax". CNN. January 3, 2002. Archived from the original on April 4, 2008. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ Thompson, Marilyn W. (September 14, 2003). "Start of rightcontent.inc". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ "Fort Detrick's anthrax mystery". Salon. January 26, 2002. Archived from the original on January 25, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ "National Defense University". www.ndu.edu. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ a b "Dr. Steven J. Hatfill's Defamation Lawsuit Against Vanity Fair and Reader's Digest Resolved – Publishers Issue Statements Retracting Implication Of Guilt" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 24, 2010. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ "Letters carried fresh anthrax". The Baltimore Sun. June 23, 2002. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ "Massive cross-contamination feared". New York Daily News. October 26, 2001. Retrieved April 22, 2025.

- ^ "U.S. Says Anthrax Germ In Mail Is 'Ames' Strain". The Washington Post. October 26, 2002. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ^ Broad, William J. (January 30, 2002). "Geographic Gaffe Misguides Anthrax Inquiry". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ Frerichs, Ralph R. "One Anthrax Answer: Ames Strain Not From Iowa". ph.ucla.edu. University of California, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ a b "FBI explains the science behind the anthrax investigation". USA Today. August 24, 2008. Archived from the original on February 16, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ Read, T. D.; Salzberg, S. L.; Pop, M.; Shumway, M.; Umayam, L.; Jiang, L.; Holtzapple, E.; Busch, J. D.; Smith, K. L.; Schupp, J. M.; Solomon, D.; Keim, P.; Fraser, C. M. (2002). "Comparative Genome Sequencing for Discovery of Novel Polymorphisms in Bacillus anthracis". Science. 296 (5575): 2028–2033. Bibcode:2002Sci...296.2028R. doi:10.1126/science.1071837. PMID 12004073. S2CID 15470665.

- ^ Frerichs, Ralph R. (November 2, 2002). "FBI Secretly Trying to Re-Create Anthrax From Mail Attacks". ph.ucla.edu. University of California, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ Rasko, David A.; Worsham, Patricia L.; et al. (March 22, 2011). "Bacillus anthracis comparative genome analysis in support of the Amerithrax investigation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (12): 5027–32. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5027R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1016657108. PMC 3064363. PMID 21383169.

- ^ "FBI Anthrax Briefing, Aug 18". Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2011 – via Google Docs.

- ^ Willman, David (September 17, 2008). "Scientist admits mistake on anthrax". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 7, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ pp. 164–193

- ^ William J. Broad, "Contradicting Some U.S. Officials, 3 Scientists Call Anthrax Powder High-Grade" Archived March 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, October 25, 2001

- ^ Weiss, Rick; Eggen, Dan (October 25, 2001). "Additive Made Spores Deadlier". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ Bernstein, Richard (February 24, 2010). "Haste Leaves Anthrax Case Unconcluded". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 28, 2010. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Epstein, Edward Jay (January 24, 2010). "The Anthrax Attacks Remain Unsolved; The FBI disproved its main theory about how the spores were weaponized". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 13, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ "Loner Likely Sent Anthrax, FBI Says". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- ^ "Official: Unusual coating in anthrax mailings". CNN. April 11, 2002. Archived from the original on August 7, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- ^ "Anthrax Sent Through Mail Gained Potency by the Letter". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- ^ "A Sophisticated Strain of Anthrax". Newsweek. Archived from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- ^ Gugliotta, Guy; Matsumoto, Gary (October 28, 2002). "Start of rightcontent.inc". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Mastumoto, Gary (November 28, 2003). "Anthrax Powder: State of the Art?". Science (magazine). Vol. 302, no. 5650. pp. 1492–1497. doi:10.1126/science.302.5650.1492.

- ^ a b c Beecher, Douglas J. (August 2006). "Forensic Application of Microbiological Culture Analysis To Identify Mail Intentionally Contaminated with Bacillus anthracis Spores". American Society for Microbiology. 72 (8): 5304–5310. Bibcode:2006ApEnM..72.5304B. doi:10.1128/AEM.00940-06. PMC 1538744. PMID 16885280.

- ^ "Science aids a nettlesome FBI criminal probe". Chemical & Engineering News. Archived from the original on April 1, 2008. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ^ Mereish, K. A. (2007). "Unsupported Conclusions on the Bacillus anthracis Spores". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 73 (15): 5074. Bibcode:2007ApEnM..73.5074M. doi:10.1128/AEM.02898-06. PMC 1951018. PMID 17660313.

- ^ a b "Anthrax Investigation / Bentonite / Cases". Vanderbilt University. October 28, 2001. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2009.

- ^ a b Greenwald, Glenn (April 11, 2007). "Response from ABC News re: the Saddam-anthrax reports". Salon. Archived from the original on August 6, 2008. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "No proof of Iraqi contamination". The Washington Times. October 29, 2001. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ a b "Tom Ridge, Other Federal Officials Brief on Anthrax". USInfo.org. Office of International Information Programs, US Department of State. October 29, 2001. Archived from the original on March 10, 2005. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ "Press Briefing by Homeland Security Director Tom Ridge". White House. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- ^ Hirota, R.; Hata, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Ishida, T.; Kuroda, A. (2010). "The Silicon Layer Supports Acid Resistance of Bacillus cereus Spores – Hirota et al. 192 (1): 111 – The Journal of Bacteriology". Journal of Bacteriology. 192 (1): 111–116. doi:10.1128/JB.00954-09. PMC 2798246. PMID 19880606.

- ^ "Small Things Considered: Through the Looking Glass: Silicate in Bacterial Spores". Schaechter.asmblog.org. January 11, 2010. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ "Peter Weber September 24, 2009 NAS presentation – audio". Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ^ Spertzel, Richard (August 5, 2008). "Bruce Ivins Wasn't the Anthrax Culprit". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 18, 2015. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Lichtblau, Eric; Wade, Nicholas (August 18, 2008). "F.B.I. Details Anthrax Case, but Doubts Remain". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Johnson, Carrie (September 17, 2008). "FBI to Get Expert Help In Anthrax Inquiry". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ Rosenberg, Eric (September 17, 2006). "5 years after terror of anthrax, case grows colder". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved December 26, 2012.

- ^ a b "A Nation Challenged: The Inquiry; Experts See F.B.I. Missteps Hampering Anthrax Inquiry". The New York Times. November 9, 2001. Archived from the original on July 5, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2011.

- ^ a b Landers, Jackson (September 12, 2016). "The Anthrax Letters That Terrorized a Nation Are Now Decontaminated and on Public View". Smithsonian Magazine. The Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved September 20, 2020.

- ^ "FBI was told to blame Anthrax scare on Al Qaeda by White House officials". Daily News. New York. August 2, 2008. Archived from the original on February 5, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2012.