Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

DNA profiling

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Forensic science |

|---|

|

DNA profiling (also called DNA fingerprinting and genetic fingerprinting) is the process of determining an individual's deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) characteristics. DNA analysis intended to identify a species, rather than an individual, is called DNA barcoding.

DNA profiling is a forensic technique in criminal investigations, comparing criminal suspects' profiles to DNA evidence so as to assess the likelihood of their involvement in the crime.[1][2] It is also used in paternity testing,[3] to establish immigration eligibility,[4] and in genealogical and medical research. DNA profiling has also been used in the study of animal and plant populations in the fields of zoology, botany, and agriculture.[5]

Background

[edit]

Starting in the mid 1970s, scientific advances allowed the use of DNA as a material for the identification of an individual. The first patent covering the direct use of DNA variation for forensics (US5593832A[6]) was issued in 1997, continued from an application first filed by Jeffrey Glassberg in 1983, based upon work he had done while at Rockefeller University in the United States in 1981.

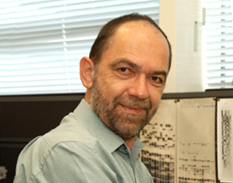

British geneticist Sir Alec Jeffreys independently developed a process for DNA profiling in 1984 while working in the Department of Genetics at the University of Leicester. Jeffreys discovered that a DNA examiner could establish patterns in unknown DNA. These patterns were a part of inherited traits that could be used to advance the field of relationship analysis. These discoveries led to the first use of DNA profiling in a criminal case.[7][8][9][10]

The process, developed by Jeffreys in conjunction with Peter Gill and Dave Werrett of the Forensic Science Service (FSS), was first used forensically in the solving of the murder of two teenagers who had been raped and murdered in Narborough, Leicestershire in 1983 and 1986. In the murder inquiry, led by Detective David Baker, the DNA contained within blood samples obtained voluntarily from around 5,000 local men who willingly assisted Leicestershire Constabulary with the investigation, resulted in the exoneration of Richard Buckland, an initial suspect who had confessed to one of the crimes, and the subsequent conviction of Colin Pitchfork on January 2, 1988. Pitchfork, a local bakery employee, had coerced his coworker Ian Kelly to stand in for him when providing a blood sample—Kelly then used a forged passport to impersonate Pitchfork. Another coworker reported the deception to the police. Pitchfork was arrested, and his blood was sent to Jeffreys' lab for processing and profile development. Pitchfork's profile matched that of DNA left by the murderer which confirmed Pitchfork's presence at both crime scenes; he pleaded guilty to both murders.[11] After some years, a chemical company named Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) introduced the first ever commercially available kit to the world. Despite being a relatively recent field, it had a significant global influence on both criminal justice system and society.[citation needed]

Although 99.9% of human DNA sequences are the same in every person, enough of the DNA is different that it is possible to distinguish one individual from another, unless they are monozygotic (identical) twins.[12] DNA profiling uses repetitive sequences that are highly variable,[12] called variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs), in particular short tandem repeats (STRs), also known as microsatellites, and minisatellites. VNTR loci are similar between closely related individuals, but are so variable that unrelated individuals are unlikely to have the same VNTRs.

Before VNTRs and STRs, people like Jeffreys used a process called restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP). This process regularly used large portions of DNA to analyze the differences between two DNA samples. RFLP was among the first technologies used in DNA profiling and analysis. However, as technology has evolved, new technologies, like STR, emerged and took the place of older technology like RFLP.[13]

The admissibility of DNA evidence in courts was disputed in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s, but has since become more universally accepted due to improved techniques.[14]

Profiling processes

[edit]DNA extraction

[edit]When a sample such as blood or saliva is obtained, the DNA is only a small part of what is present in the sample. Before the DNA can be analyzed, it must be extracted from the cells and purified. There are many ways this can be accomplished, but all methods follow the same basic procedure. The cell and nuclear membranes need to be broken up to allow the DNA to be free in solution. Once the DNA is free, it can be separated from all other cellular components. After the DNA has been separated in solution, the remaining cellular debris can then be removed from the solution and discarded, leaving only DNA. The most common methods of DNA extraction include organic extraction (also called phenol–chloroform extraction),[15] Chelex extraction, and solid-phase extraction. Differential extraction is a modified version of extraction in which DNA from two different types of cells can be separated from each other before being purified from the solution. Each method of extraction works well in the laboratory, but analysts typically select their preferred method based on factors such as the cost, the time involved, the quantity of DNA yielded, and the quality of DNA yielded.[16][17]

RFLP analysis

[edit]

RFLP stands for restriction fragment length polymorphism and, in terms of DNA analysis, describes a DNA testing method which utilizes restriction enzymes to "cut" the DNA at short and specific sequences throughout the sample. To start off processing in the laboratory, the sample has to first go through an extraction protocol, which may vary depending on the sample type or laboratory SOPs (Standard Operating Procedures). Once the DNA has been "extracted" from the cells within the sample and separated away from extraneous cellular materials and any nucleases that would degrade the DNA, the sample can then be introduced to the desired restriction enzymes to be cut up into discernable fragments. Following the enzyme digestion, a Southern Blot is performed. Southern Blots are a size-based separation method that are performed on a gel with either radioactive or chemiluminescent probes. RFLP could be conducted with single-locus or multi-locus probes (probes which target either one location on the DNA or multiple locations on the DNA). Incorporating the multi-locus probes allowed for higher discrimination power for the analysis, however completion of this process could take several days to a week for one sample due to the extreme amount of time required by each step required for visualization of the probes.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis

[edit]This technique was developed in 1983 by Kary Mullis. PCR is now a common and important technique used in medical and biological research labs for a variety of applications.[18]

PCR, or Polymerase Chain Reaction, is a widely used molecular biology technique to amplify a specific DNA sequence.

Amplification is achieved by a series of three steps:

1- Denaturation : In this step, the DNA is heated to 95 °C to dissociate the hydrogen bonds between the complementary base pairs of the double-stranded DNA.

2-Annealing : During this stage the reaction is cooled to 50-65 °C . This enables the primers to attach to a specific location on the single -stranded template DNA by way of hydrogen bonding.

3-Extension : A thermostable DNA polymerase which is Taq polymerase is commonly used at this step. This is done at a temperature of 72 °C . DNA polymerase adds nucleotides in the 5'-3' direction and synthesizes the complementary strand of the DNA template .

STR analysis

[edit]

The system of DNA profiling used today is based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and uses simple sequences.[8]

From country to country, different STR-based DNA-profiling systems are in use. In North America, systems that amplify the CODIS 20[20] core loci are almost universal, whereas in the United Kingdom the DNA-17 loci system is in use, and Australia uses 18 core markers.[21]

The true power of STR analysis is in its statistical power of discrimination. Because the 20 loci that are currently used for discrimination in CODIS are independently assorted (having a certain number of repeats at one locus does not change the likelihood of having any number of repeats at any other locus), the product rule for probabilities can be applied. This means that, if someone has the DNA type of ABC, where the three loci were independent, then the probability of that individual having that DNA type is the probability of having type A times the probability of having type B times the probability of having type C. This has resulted in the ability to generate match probabilities of 1 in a quintillion (1x1018) or more.[further explanation needed] However, DNA database searches showed much more frequent than expected false DNA profile matches.[22]

Y-chromosome analysis

[edit]Due to the paternal inheritance, Y-haplotypes provide information about the genetic ancestry of the male population. To investigate this population history, and to provide estimates for haplotype frequencies in criminal casework, the "Y haplotype reference database (YHRD)" has been created in 2000 as an online resource. It currently comprises more than 300,000 minimal (8 locus) haplotypes from world-wide populations.[23]

Mitochondrial analysis

[edit]mtDNA can be obtained from such material as hair shafts and old bones/teeth.[24] Control mechanism based on interaction point with data. This can be determined by tooled placement in sample.[25]

Issues with forensic DNA samples

[edit]When people think of DNA analysis, they often think about television shows like NCIS or CSI, which portray DNA samples coming into a lab and being instantly analyzed, followed by the pulling up of a picture of the suspect within minutes. However, the reality is quite different, and perfect DNA samples are often not collected from the scene of a crime. Homicide victims are frequently left exposed to harsh conditions before they are found, and objects that are used to commit crimes have often been handled by more than one person. The two most prevalent issues that forensic scientists encounter when analyzing DNA samples are degraded samples and DNA mixtures.[26]

Degraded DNA

[edit]Before modern PCR methods existed, it was almost impossible to analyze degraded DNA samples. Methods like restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), which was the first technique used for DNA analysis in forensic science, required high molecular weight DNA in the sample in order to get reliable data. High molecular weight DNA, however, is lacking in degraded samples, as the DNA is too fragmented to carry out RFLP accurately. It was only when polymerase chain reaction techniques were invented that analysis of degraded DNA samples were able to be carried out. Multiplex PCR in particular made it possible to isolate and to amplify the small fragments of DNA that are still left in degraded samples. When multiplex PCR methods are compared to the older methods like RFLP, a vast difference can be seen. Multiplex PCR can theoretically amplify less than 1 ng of DNA, but RFLP had to have a least 100 ng of DNA in order to carry out an analysis.[27]

Low-template DNA

[edit]Low-template DNA can happen when there is less than 0.1 ng([28]) of DNA in a sample. This can lead to more stochastic effects (random events) such as allelic dropout or allelic drop-in which can alter the interpretation of a DNA profile. These stochastic effects can lead to the unequal amplification of the 2 alleles that come from a heterozygous individual. It is especially important to take low-template DNA into account when dealing with a mixture of DNA sample. This is because for one (or more) of the contributors in the mixture, they are more likely to have less than the optimal amount of DNA for the PCR reaction to work properly.[29] Therefore, stochastic thresholds are developed for DNA profile interpretation. The stochastic threshold is the minimum peak height (RFU value), seen in an electropherogram where dropout occurs. If the peak height value is above this threshold, then it is reasonable to assume that allelic dropout has not occurred. For example, if only 1 peak is seen for a particular locus in the electropherogram but its peak height is above the stochastic threshold, then we can reasonably assume that this individual is homozygous and is not missing its heterozygous partner allele that otherwise would have dropped out due to having low-template DNA. Allelic dropout can occur when there is low-template DNA because there is such little DNA to start with that at this locus the contributor to the DNA sample (or mixture) is a true heterozygote but the other allele is not amplified and so it would be lost. Allelic drop-in[30] can also occur when there is low-template DNA because sometimes the stutter peak can be amplified. The stutter is an artifact of PCR. During the PCR reaction, DNA Polymerase will come in and add nucleotides off of the primer, but this whole process is very dynamic, meaning that the DNA Polymerase is constantly binding, popping off and then rebinding. Therefore, sometimes DNA Polymerase will rejoin at the short tandem repeat ahead of it, leading to a short tandem repeat that is 1 repeat less than the template. During PCR, if DNA Polymerase happens to bind to a locus in stutter and starts to amplify it to make lots of copies, then this stutter product will appear randomly in the electropherogram, leading to allelic drop-in.

MiniSTR analysis

[edit]In instances in which DNA samples are degraded, like if there are intense fires or all that remains are bone fragments, standard STR testing on those samples can be inadequate. When standard STR testing is done on highly degraded samples, the larger STR loci often drop out, and only partial DNA profiles are obtained. Partial DNA profiles can be a powerful tool, but the probability of a random match is larger than if a full profile was obtained. One method that has been developed to analyse degraded DNA samples is to use miniSTR technology. In the new approach, primers are specially designed to bind closer to the STR region.[31]

In normal STR testing, the primers bind to longer sequences that contain the STR region within the segment. MiniSTR analysis, however, targets only the STR location, which results in a DNA product that is much smaller.[31]

By placing the primers closer to the actual STR regions, there is a higher chance that successful amplification of this region will occur. Successful amplification of those STR regions can now occur, and more complete DNA profiles can be obtained. The success that smaller PCR products produce a higher success rate with highly degraded samples was first reported in 1995, when miniSTR technology was used to identify victims of the Waco fire.[32]

DNA mixtures

[edit]Mixtures are another common issue faced by forensic scientists when they are analyzing unknown or questionable DNA samples. A mixture is defined as a DNA sample that contains two or more individual contributors.[27] That can often occur when a DNA sample is swabbed from an item that is handled by more than one person or when a sample contains both the victim's and the assailant's DNA. The presence of more than one individual in a DNA sample can make it challenging to detect individual profiles, and interpretation of mixtures should be performed only by highly trained individuals. Mixtures that contain two or three individuals can be interpreted with difficulty. Mixtures that contain four or more individuals are much too convoluted to get individual profiles. One common scenario in which a mixture is often obtained is in the case of sexual assault. A sample may be collected that contains material from the victim, the victim's consensual sexual partners, and the perpetrator(s).[33]

Mixtures can generally be sorted into three categories: Type A, Type B, and Type C.[34] Type A mixtures have alleles with similar peak-heights all around, so the contributors cannot be distinguished from each other. Type B mixtures can be deconvoluted by comparing peak-height ratios to determine which alleles were donated together. Type C mixtures cannot be safely interpreted with current technology because the samples were affected by DNA degradation or having too small a quantity of DNA present.

When looking at an electropherogram, it is possible to determine the number of contributors in less complex mixtures based on the number of peaks located in each locus. In comparison to a single source profile, which will only have one or two peaks at each locus, a mixture is when there are three or more peaks at two or more loci.[35] If there are three peaks at only a single locus, then it is possible to have a single contributor who is tri-allelic at that locus.[36] Two person mixtures will have between two and four peaks at each locus, and three person mixtures will have between three and six peaks at each locus. Mixtures become increasingly difficult to deconvolute as the number of contributors increases.

As detection methods in DNA profiling advance, forensic scientists are seeing more DNA samples that contain mixtures, as even the smallest contributor can now be detected by modern tests. The ease in which forensic scientists have in interpenetrating DNA mixtures largely depends on the ratio of DNA present from each individual, the genotype combinations, and the total amount of DNA amplified.[37] The DNA ratio is often the most important aspect to look at in determining whether a mixture can be interpreted. For example, if a DNA sample had two contributors, it would be easy to interpret individual profiles if the ratio of DNA contributed by one person was much higher than the second person. When a sample has three or more contributors, it becomes extremely difficult to determine individual profiles. Fortunately, advancements in probabilistic genotyping may make that sort of determination possible in the future. Probabilistic genotyping uses complex computer software to run through thousands of mathematical computations to produce statistical likelihoods of individual genotypes found in a mixture.[38]

DNA profiling in plant:

Plant DNA profiling (fingerprinting) is a method for identifying cultivars that uses molecular marker techniques. This method is gaining attention due to Trade Related Intellectual property rights (TRIPs) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).[39]

Advantages of Plant DNA profiling:

Identification, authentication, specific distinction, detecting adulteration and identifying phytoconstituents are all possible with DNA fingerprinting in medical plants.[40]

DNA based markers are critical for these applications, determining the future of scientific study in pharmacognosy.[40]

It also helps with determining the traits (such as seed size and leaf color) are likely to improve the offspring or not.[41]

DNA databases

[edit]An early application of a DNA database was the compilation of a Mitochondrial DNA Concordance,[42] prepared by Kevin W. P. Miller and John L. Dawson at the University of Cambridge from 1996 to 1999[43] from data collected as part of Miller's PhD thesis. There are now several DNA databases in existence around the world. Some are private, but most of the largest databases are government-controlled. The United States maintains the largest DNA database, with the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) holding over 13 million records as of May 2018.[44] The United Kingdom maintains the National DNA Database (NDNAD), which is of similar size, despite the UK's smaller population. The size of this database, and its rate of growth, are giving concern to civil liberties groups in the UK, where police have wide-ranging powers to take samples and retain them even in the event of acquittal.[45] The Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition partially addressed these concerns with part 1 of the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012, under which DNA samples must be deleted if suspects are acquitted or not charged, except in relation to certain (mostly serious or sexual) offenses. Public discourse around the introduction of advanced forensic techniques (such as genetic genealogy using public genealogy databases and DNA phenotyping approaches) has been limited, disjointed, unfocused, and raises issues of privacy and consent that may warrant the establishment of additional legal protections.[46]

The U.S. Patriot Act of the United States provides a means for the U.S. government to get DNA samples from suspected terrorists. DNA information from crimes is collected and deposited into the CODIS database, which is maintained by the FBI. CODIS enables law enforcement officials to test DNA samples from crimes for matches within the database, providing a means of finding specific biological profiles associated with collected DNA evidence.[47]

When a match is made from a national DNA databank to link a crime scene to an offender having provided a DNA sample to a database, that link is often referred to as a cold hit. A cold hit is of value in referring the police agency to a specific suspect but is of less evidential value than a DNA match made from outside the DNA Databank.[48]

FBI agents cannot legally store DNA of a person not convicted of a crime. DNA collected from a suspect not later convicted must be disposed of and not entered into the database. In 1998, a man residing in the UK was arrested on accusation of burglary. His DNA was taken and tested, and he was later released. Nine months later, this man's DNA was accidentally and illegally entered in the DNA database. New DNA is automatically compared to the DNA found at cold cases and, in this case, this man was found to be a match to DNA found at a rape and assault case one year earlier. The government then prosecuted him for these crimes. During the trial the DNA match was requested to be removed from the evidence because it had been illegally entered into the database. The request was carried out.[49] The DNA of the perpetrator, collected from victims of rape, can be stored for years until a match is found. In 2014, to address this problem, Congress extended a bill that helps states deal with "a backlog" of evidence.[50]

DNA profiling databases in Plants:

PIDS:

PIDS(Plant international DNA-fingerprinting system) is an open source web server and free software based plant international DNA fingerprinting system.

It manages huge amount of microsatellite DNA fingerprint data, performs genetic studies, and automates collection, storage and maintenance while decreasing human error and increasing efficiency.

The system may be tailored to specific laboratory needs, making it a valuable tool for plant breeders, forensic science, and human fingerprint recognition.

It keeps track of experiments, standardizes data and promotes inter-database communication.

It also helps with the regulation of variety quality, the preservation of variety rights and the use of molecular markers in breeding by providing location statistics, merging, comparison and genetic analysis function.[51]

Considerations in evaluating DNA evidence

[edit]When using RFLP, the theoretical risk of a coincidental match is 1 in 100 billion (100,000,000,000) although the practical risk is actually 1 in 1,000 because monozygotic twins are 0.2% of the human population.[52] Moreover, the rate of laboratory error is almost certainly higher than that and actual laboratory procedures often do not reflect the theory under which the coincidence probabilities were computed. For example, coincidence probabilities may be calculated based on the probabilities that markers in two samples have bands in precisely the same location, but a laboratory worker may conclude that similar but not precisely-identical band patterns result from identical genetic samples with some imperfection in the agarose gel. However, in that case, the laboratory worker increases the coincidence risk by expanding the criteria for declaring a match. Studies conducted in the 2000s quoted relatively-high error rates, which may be cause for concern.[53] In the early days of genetic fingerprinting, the necessary population data to compute a match probability accurately was sometimes unavailable. Between 1992 and 1996, arbitrary-low ceilings were controversially put on match probabilities used in RFLP analysis, rather than the higher theoretically computed ones.[54]

Evidence of genetic relationship

[edit]It is possible to use DNA profiling as evidence of genetic relationship although such evidence varies in strength from weak to positive. Testing that shows no relationship is absolutely certain. Further, while almost all individuals have a single and distinct set of genes, ultra-rare individuals, known as "chimeras", have at least two different sets of genes. There have been two cases of DNA profiling that falsely suggested that a mother was unrelated to her children.[55]

Fake DNA evidence

[edit]The functional analysis of genes and their coding sequences (open reading frames [ORFs]) typically requires that each ORF be expressed, the encoded protein purified, antibodies produced, phenotypes examined, intracellular localization determined, and interactions with other proteins sought.[56] In a study conducted by the life science company Nucleix and published in the journal Forensic Science International, scientists found that an in vitro synthesized sample of DNA matching any desired genetic profile can be constructed using standard molecular biology techniques without obtaining any actual tissue from that person.

DNA evidence in criminal trials

[edit]| Evidence |

|---|

| Part of the law series |

| Types of evidence |

| Relevance |

| Authentication |

| Witnesses |

| Hearsay and exceptions |

| Other common law areas |

Familial DNA searching

[edit]Familial DNA searching (sometimes referred to as "familial DNA" or "familial DNA database searching") is the practice of creating new investigative leads in cases where DNA evidence found at the scene of a crime (forensic profile) strongly resembles that of an existing DNA profile (offender profile) in a state DNA database but there is not an exact match.[57][58] After all other leads have been exhausted, investigators may use specially developed software to compare the forensic profile to all profiles taken from a state's DNA database to generate a list of those offenders already in the database who are most likely to be a very close relative of the individual whose DNA is in the forensic profile.[59]

Familial DNA database searching was first used in an investigation leading to the conviction of Jeffrey Gafoor of the murder of Lynette White in the United Kingdom on 4 July 2003. DNA evidence was matched to Gafoor's nephew, who at 14 years old had not been born at the time of the murder in 1988. It was used again in 2004[60] to find a man who threw a brick from a motorway bridge and hit a lorry driver, killing him. DNA found on the brick matched that found at the scene of a car theft earlier in the day, but there were no good matches on the national DNA database. A wider search found a partial match to an individual; on being questioned, this man revealed he had a brother, Craig Harman, who lived very close to the original crime scene. Harman voluntarily submitted a DNA sample, and confessed when it matched the sample from the brick.[61] As of 2011, familial DNA database searching is not conducted on a national level in the United States, where states determine how and when to conduct familial searches. The first familial DNA search with a subsequent conviction in the United States was conducted in Denver, Colorado, in 2008, using software developed under the leadership of Denver District Attorney Mitch Morrissey and Denver Police Department Crime Lab Director Gregg LaBerge.[62] California was the first state to implement a policy for familial searching under then-Attorney General Jerry Brown, who later became Governor.[63] In his role as consultant to the Familial Search Working Group of the California Department of Justice, former Alameda County Prosecutor Rock Harmon is widely considered to have been the catalyst in the adoption of familial search technology in California. The technique was used to catch the Los Angeles serial killer known as the "Grim Sleeper" in 2010.[64] It was not a witness or informant that tipped off law enforcement to the identity of the "Grim Sleeper" serial killer, who had eluded police for more than two decades, but DNA from the suspect's own son. The suspect's son had been arrested and convicted in a felony weapons charge and swabbed for DNA the year before. When his DNA was entered into the database of convicted felons, detectives were alerted to a partial match to evidence found at the "Grim Sleeper" crime scenes. David Franklin Jr., also known as the Grim Sleeper, was charged with ten counts of murder and one count of attempted murder.[65] More recently, familial DNA led to the arrest of 21-year-old Elvis Garcia on charges of sexual assault and false imprisonment of a woman in Santa Cruz in 2008.[66] In March 2011 Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell announced that Virginia would begin using familial DNA searches.[67]

At a press conference in Virginia on 7 March 2011, regarding the East Coast Rapist, Prince William County prosecutor Paul Ebert and Fairfax County Police Detective John Kelly said the case would have been solved years ago if Virginia had used familial DNA searching. Aaron Thomas, the suspected East Coast Rapist, was arrested in connection with the rape of 17 women from Virginia to Rhode Island, but familial DNA was not used in the case.[68]

Critics of familial DNA database searches argue that the technique is an invasion of an individual's 4th Amendment rights.[69] Privacy advocates are petitioning for DNA database restrictions, arguing that the only fair way to search for possible DNA matches to relatives of offenders or arrestees would be to have a population-wide DNA database.[49] Some scholars have pointed out that the privacy concerns surrounding familial searching are similar in some respects to other police search techniques,[70] and most have concluded that the practice is constitutional.[71] The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in United States v. Pool (vacated as moot) suggested that this practice is somewhat analogous to a witness looking at a photograph of one person and stating that it looked like the perpetrator, which leads law enforcement to show the witness photos of similar looking individuals, one of whom is identified as the perpetrator.[72]

Critics also state that racial profiling could occur on account of familial DNA testing. In the United States, the conviction rates of racial minorities are much higher than that of the overall population. It is unclear whether this is due to discrimination from police officers and the courts, as opposed to a simple higher rate of offence among minorities. Arrest-based databases, which are found in the majority of the United States, lead to an even greater level of racial discrimination. An arrest, as opposed to conviction, relies much more heavily on police discretion.[49]

For instance, investigators with Denver District Attorney's Office successfully identified a suspect in a property theft case using a familial DNA search. In this example, the suspect's blood left at the scene of the crime strongly resembled that of a current Colorado Department of Corrections prisoner.[62]

Partial matches

[edit]Partial DNA matches are the result of moderate stringency CODIS searches that produce a potential match that shares at least one allele at every locus.[73] Partial matching does not involve the use of familial search software, such as those used in the United Kingdom and the United States, or additional Y-STR analysis and therefore often misses sibling relationships. Partial matching has been used to identify suspects in several cases in both countries[74] and has also been used as a tool to exonerate the falsely accused. Darryl Hunt was wrongly convicted in connection with the rape and the murder of a young woman in 1984 in North Carolina.[75]

Surreptitious DNA collecting

[edit]Police forces may collect DNA samples without a suspect's knowledge, and use it as evidence. The legality of the practice has been questioned in Australia.[76]

In the United States, where it has been accepted, courts often rule that there is no expectation of privacy and cite California v. Greenwood (1988), in which the Supreme Court held that the Fourth Amendment does not prohibit the warrantless search and seizure of garbage left for collection outside the curtilage of a home. Critics of this practice underline that this analogy ignores that "most people have no idea that they risk surrendering their genetic identity to the police by, for instance, failing to destroy a used coffee cup. Moreover, even if they do realize it, there is no way to avoid abandoning one's DNA in public."[77]

The United States Supreme Court ruled in Maryland v. King (2013) that DNA sampling of prisoners arrested for serious crimes is constitutional.[78][79][80]

In the United Kingdom, the Human Tissue Act 2004 prohibits private individuals from covertly collecting biological samples (hair, fingernails, etc.) for DNA analysis but exempts medical and criminal investigations from the prohibition.[81]

England and Wales

[edit]Evidence from an expert who has compared DNA samples must be accompanied by evidence as to the sources of the samples and the procedures for obtaining the DNA profiles.[82] The judge must ensure that the jury must understand the significance of DNA matches and mismatches in the profiles. The judge must also ensure that the jury does not confuse the match probability (the probability that a person that is chosen at random has a matching DNA profile to the sample from the scene) with the probability that a person with matching DNA committed the crime. In 1996 R v. Doheny[83]

Juries should weigh up conflicting and corroborative evidence, using their own common sense and not by using mathematical formulae, such as Bayes' theorem, so as to avoid "confusion, misunderstanding and misjudgment".[84]

Presentation and evaluation of evidence of partial or incomplete DNA profiles

[edit]In R v Bates,[85] Moore-Bick LJ said:

We can see no reason why partial profile DNA evidence should not be admissible provided that the jury are made aware of its inherent limitations and are given a sufficient explanation to enable them to evaluate it. There may be cases where the match probability in relation to all the samples tested is so great that the judge would consider its probative value to be minimal and decide to exclude the evidence in the exercise of his discretion, but this gives rise to no new question of principle and can be left for decision on a case by case basis. However, the fact that there exists in the case of all partial profile evidence the possibility that a "missing" allele might exculpate the accused altogether does not provide sufficient grounds for rejecting such evidence. In many there is a possibility (at least in theory) that evidence that would assist the accused and perhaps even exculpate him altogether exists, but that does not provide grounds for excluding relevant evidence that is available and otherwise admissible, though it does make it important to ensure that the jury are given sufficient information to enable them to evaluate that evidence properly.[86]

DNA testing in the United States

[edit]

There are state laws on DNA profiling in all 50 states of the United States.[87] Detailed information on database laws in each state can be found at the National Conference of State Legislatures website.[88]

Development of artificial DNA

[edit]In August 2009, scientists in Israel raised serious doubts concerning the use of DNA by law enforcement as the ultimate method of identification. In a paper published in the journal Forensic Science International: Genetics, the Israeli researchers demonstrated that it is possible to manufacture DNA in a laboratory, thus falsifying DNA evidence. The scientists fabricated saliva and blood samples, which originally contained DNA from a person other than the supposed donor of the blood and saliva.[89]

The researchers also showed that, using a DNA database, it is possible to take information from a profile and manufacture DNA to match it, and that this can be done without access to any actual DNA from the person whose DNA they are duplicating. The synthetic DNA oligos required for the procedure are common in molecular laboratories.[89]

The New York Times quoted the lead author, Daniel Frumkin, saying, "You can just engineer a crime scene ... any biology undergraduate could perform this".[89] Frumkin perfected a test that can differentiate real DNA samples from fake ones. His test detects epigenetic modifications, in particular, DNA methylation.[90] Seventy percent of the DNA in any human genome is methylated, meaning it contains methyl group modifications within a CpG dinucleotide context. Methylation at the promoter region is associated with gene silencing. The synthetic DNA lacks this epigenetic modification, which allows the test to distinguish manufactured DNA from genuine DNA.[89]

It is unknown how many police departments, if any, currently use the test. No police lab has publicly announced that it is using the new test to verify DNA results.[91]

Researchers at the University of Tokyo integrated an artificial DNA replication scheme with a rebuilt gene expression system and micro-compartmentalization utilizing cell-free materials alone for the first time. Multiple cycles of serial dilution were performed on a system contained in microscale water-in-oil droplets.[92]

Chances of making DNA change on purpose

Overall, this study's artificial genomic DNA, which kept copying itself using self-encoded proteins and made its sequence better on its own, is a good starting point for making more complex artificial cells. By adding the genes needed for transcription and translation to artificial genomic DNA, it may be possible in the future to make artificial cells that can grow on their own when fed small molecules like amino acids and nucleotides. Using living organisms to make useful things, like drugs and food, would be more stable and easier to control in these artificial cells.[92]

On July 7, 2008, the American chemical society reported that Japanese chemists have created the world's first DNA molecule comprised nearly completely of synthetic components.

A nano-particle based artificial transcription factor for gene regulation:

Nano Script is a nanoparticle-based artificial transcription factor that is supposed to replicate the structure and function of TFs. On gold nanoparticles, functional peptides and tiny molecules referred to as synthetic transcription factors, which imitate the various TF domains, were attached to create Nano Script. We show that Nano Script localizes to the nucleus and begins transcription of a reporter plasmid by an amount more than 15-fold. Moreover, Nano Script can successfully transcribe targeted genes onto endogenous DNA in a nonviral manner.[93]

Three different fluorophores—red, green, and blue—were carefully fixed on the DNA rod surface to provide spatial information and create a nanoscale barcode. Epifluorescence and total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy reliably deciphered spatial information between fluorophores. By moving the three fluorophores on the DNA rod, this nanoscale barcode created 216 fluorescence patterns.[94]

Cases

[edit]- In 1986, Richard Buckland was exonerated, despite having admitted to the rape and murder of a teenager near Leicester, the city where DNA profiling was first developed. This was the first use of DNA fingerprinting in a criminal investigation, and the first to prove a suspect's innocence.[95] The following year Colin Pitchfork was identified as the perpetrator of the same murder, in addition to another, using the same techniques that had cleared Buckland.[96]

- In 1987, genetic fingerprinting was used in a US criminal court for the first time in the trial of a man accused of unlawful intercourse with a mentally disabled 14-year-old female who gave birth to a baby.[97]

- In 1987, Florida rapist Tommie Lee Andrews was the first person in the United States to be convicted as a result of DNA evidence, for raping a woman during a burglary; he was convicted on 6 November 1987, and sentenced to 22 years in prison.[98][99]

- In 1990, a violent murder of a young student in Brno was the first criminal case in Czechoslovakia solved by DNA evidence, with the murderer sentenced to 23 years in prison.[100][101]

- In 1992, DNA from a palo verde tree was used to convict Mark Alan Bogan of murder. DNA from seed pods of a tree at the crime scene was found to match that of seed pods found in Bogan's truck. This is the first instance of plant DNA admitted in a criminal case.[102][103][104]

- In 1994, the claim that Anna Anderson was Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna of Russia was tested after her death using samples of her tissue that had been stored at a Charlottesville hospital following a medical procedure. The tissue was tested using DNA fingerprinting, and showed that she bore no relation to the Romanovs.[105]

- In 1994, Earl Washington, Jr., of Virginia had his death sentence commuted to life imprisonment a week before his scheduled execution date based on DNA evidence. He received a full pardon in 2000 based on more advanced testing.[106]

- In 1999, Raymond Easton, a disabled man from Swindon, England, was arrested and detained for seven hours in connection with a burglary, because the on-site DNA seemed to match his. He was released when a more accurate test showed clear differences. His DNA had been retained on file after an unrelated domestic incident some time previously.[107]

- In 2000 Frank Lee Smith was proved innocent by DNA profiling of the murder of an eight-year-old girl after spending 14 years on death row in Florida, USA. However he had died of cancer just before his innocence was proven.[108] In view of this the Florida state governor ordered that in future any death row inmate claiming innocence should have DNA testing.[106]

- In May 2000 Gordon Graham murdered Paul Gault at his home in Lisburn, Northern Ireland. Graham was convicted of the murder when his DNA was found on a sports bag left in the house as part of an elaborate ploy to suggest the murder occurred after a burglary had gone wrong. Graham was having an affair with the victim's wife at the time of the murder. It was the first time Low Copy Number DNA was used in Northern Ireland.[109]

- In 2001, Wayne Butler was convicted for the murder of Celia Douty. It was the first murder in Australia to be solved using DNA profiling.[110][111]

- In 2002, the body of James Hanratty, hanged in 1962 for the "A6 murder", was exhumed and DNA samples from the body and members of his family were analysed. The results convinced Court of Appeal judges that Hanratty's guilt, which had been strenuously disputed by campaigners, was proved "beyond doubt".[112] Paul Foot and some other campaigners continued to believe in Hanratty's innocence and argued that the DNA evidence could have been contaminated, noting that the small DNA samples from items of clothing, kept in a police laboratory for over 40 years "in conditions that do not satisfy modern evidential standards", had had to be subjected to very new amplification techniques in order to yield any genetic profile.[113] However, no DNA other than Hanratty's was found on the evidence tested, contrary to what would have been expected had the evidence indeed been contaminated.[114]

- In August 2002, Annalisa Vicentini was shot dead in Tuscany. Bartender Peter Hamkin, 23, was arrested, in Merseyside in March 2003 on an extradition warrant heard at Bow Street Magistrates' Court in London to establish whether he should be taken to Italy to face a murder charge. DNA "proved" he shot her, but he was cleared on other evidence.[115]

- In 2003, Welshman Jeffrey Gafoor was convicted of the 1988 murder of Lynette White, when crime scene evidence collected 12 years earlier was re-examined using STR techniques, resulting in a match with his nephew.[116]

- In June 2003, because of new DNA evidence, Dennis Halstead, John Kogut and John Restivo won a re-trial on their 1986 murder conviction, their convictions were struck down and they were released.[117]

- In 2004, DNA testing shed new light into the mysterious 1912 disappearance of Bobby Dunbar, a four-year-old boy who vanished during a fishing trip. He was allegedly found alive eight months later in the custody of William Cantwell Walters, but another woman claimed that the boy was her son, Bruce Anderson, whom she had entrusted in Walters' custody. The courts disbelieved her claim and convicted Walters for the kidnapping. The boy was raised and known as Bobby Dunbar throughout the rest of his life. However, DNA tests on Dunbar's son and nephew revealed the two were not related, thus establishing that the boy found in 1912 was not Bobby Dunbar, whose real fate remains unknown.[118]

- In 2005, Gary Leiterman was convicted of the 1969 murder of Jane Mixer, a law student at the University of Michigan, after DNA found on Mixer's pantyhose was matched to Leiterman. DNA in a drop of blood on Mixer's hand was matched to John Ruelas, who was only four years old in 1969 and was never successfully connected to the case in any other way. Leiterman's defense unsuccessfully argued that the unexplained match of the blood spot to Ruelas pointed to cross-contamination and raised doubts about the reliability of the lab's identification of Leiterman.[119][120]

- In November 2008, Anthony Curcio was arrested for masterminding one of the most elaborately planned armored car heists in history. DNA evidence linked Curcio to the crime.[121]

- In March 2009, Sean Hodgson—convicted of 1979 killing of Teresa De Simone, 22, in her car in Southampton—was released after tests proved DNA from the scene was not his. It was later matched to DNA retrieved from the exhumed body of David Lace. Lace had previously confessed to the crime but was not believed by the detectives. He served time in prison for other crimes committed at the same time as the murder and then committed suicide in 1988.[122]

- In 2012, a case of babies being switched, many decades earlier, was discovered by accident. After undertaking DNA testing for other purposes, Alice Collins Plebuch was advised that her ancestry appeared to include a significant Ashkenazi Jewish component, despite a belief in her family that they were of predominantly Irish descent. Profiling of Plebuch's genome suggested that it included distinct and unexpected components associated with Ashkenazi, Middle Eastern, and Eastern European populations. This led Plebuch to conduct an extensive investigation, after which she concluded that her father had been switched (possibly accidentally) with another baby soon after birth. Plebuch was also able to identify the biological ancestors of her father.[123][124]

- In 2016 Anthea Ring, abandoned as a baby, was able to use a DNA sample and DNA matching database to discover her deceased mother's identity and roots in County Mayo, Ireland. A recently developed forensic test was subsequently used to capture DNA from saliva left on old stamps and envelopes by her suspected father, uncovered through painstaking genealogy research. The DNA in the first three samples was too degraded to use. However, on the fourth, more than enough DNA was found. The test, which has a degree of accuracy acceptable in UK courts, proved that a man named Patrick Coyne was her biological father.[125][126]

- In 2018 the Buckskin girl (a body found in 1981 in Ohio) was identified as Marcia King from Arkansas using DNA genealogical techniques[127]

- In 2018 Joseph James DeAngelo was arrested as the main suspect for the Golden State Killer using DNA and genealogy techniques.[128]

- In 2018, William Earl Talbott II was arrested as a suspect for the 1987 murders of Jay Cook and Tanya Van Cuylenborg with the assistance of genealogical DNA testing. The same genetic genealogist that helped in this case also helped police with 18 other arrests in 2018.[129]

- In 2018, with the use of Next Generation Identification System's enhanced biometric capabilities, the FBI matched the fingerprint of a suspect named Timothy David Nelson and arrested him 20 years after the alleged sexual assault.[130]

DNA evidence as evidence to prove rights of succession to British titles

[edit]DNA testing has been used to establish the right of succession to British titles.[131]

Cases:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Eureka moment that led to the discovery of DNA fingerprinting". The Guardian. 24 May 2009. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Murphy E (13 October 2017). "Forensic DNA Typing". Annual Review of Criminology. 1: 497–515. doi:10.1146/annurev-criminol-032317-092127.

- ^ Petersen, K., J.. Handbook of Surveillance Technologies. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL. CRC Press, 2012. p815

- ^ "DNA pioneer's 'eureka' momen". BBC. 9 September 2009. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ Chambers GK, Curtis C, Millar CD, Huynen L, Lambert DM (February 2014). "DNA fingerprinting in zoology: past, present, future". Investigative Genetics. 5 (1) 3. doi:10.1186/2041-2223-5-3. PMC 3909909. PMID 24490906.

- ^ "US5593832.pdf" (PDF). docs.google.com. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Wickenheiser, Ray A. (12 July 2019). "Forensic genealogy, bioethics and the Golden State Killer case". Forensic Science International. Synergy. 1: 114–125. doi:10.1016/j.fsisyn.2019.07.003. PMC 7219171. PMID 32411963.

- ^ a b Tautz D (1989). "Hypervariability of simple sequences as a general source for polymorphic DNA markers". Nucleic Acids Research. 17 (16): 6463–6471. doi:10.1093/nar/17.16.6463. PMC 318341. PMID 2780284.

- ^ US 5766847, Jäckle, Herbert & Tautz, Diethard, "Process for analyzing length polymorphisms in DNA regions", published 16 June 1998, assigned to Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Forderung der Wissenschaften

- ^ Jeffreys AJ (November 2013). "The man behind the DNA fingerprints: an interview with Professor Sir Alec Jeffreys". Investigative Genetics. 4 (1): 21. doi:10.1186/2041-2223-4-21. PMC 3831583. PMID 24245655.

- ^ Evans C (2007) [1998]. The Casebook of Forensic Detection: How Science Solved 100 of the World's Most Baffling Crimes (2nd ed.). New York: Berkeley Books. p. 86–89. ISBN 978-1440620539.

- ^ a b "Use of DNA in Identification". Accessexcellence.org. Archived from the original on 26 April 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ Marks, Kathy (June 2009). "New DNA Technology for Cold Cases". Law & Order. 57 (6): 36–38, 40–41, 43. ProQuest 1074789441.

- ^ Roth, Andrea (2020). "Chapter 13: Admissibility of DNA Evidence in Court" (PDF). University of California Berkeley School of Law. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

The original forms of forensic DNA testing and interpretation used in the 1980s and early 1990s were subject to much criticism during the "DNA Wars," the history of which has been ably told by others (Kaye, 2010; Lynch et al., 2008; see chapter 1). But these earlier techniques have been replaced in forensic DNA analysis by PCR- based STR discrete- allele typing. Courts now universally accept as generally reliable both the PCR process for amplification of DNA and the STR- based system of identifying and comparing alleles (Kaye, 2010, pp. 190– 191).

- ^ "Organic Extraction Method - US". www.thermofisher.com. Retrieved 7 August 2025.

- ^ Rana, Ajay K (August 2025). "Challenging biological samples and strategies for DNA extraction". Journal of Investigative Medicine. 73 (6): 443–459. doi:10.1177/10815589251327503. PMID 40033560.

- ^ Butler JM (2005). Forensic DNA typing: biology, technology, and genetics of STR markers (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 978-0080470610. OCLC 123448124.[page needed]

- ^ Rahman, Md Tahminur; Uddin, Muhammed Salah; Sultana, Razia; Moue, Arumina; Setu, Muntahina (6 February 2013). "Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): A Short Review". Anwer Khan Modern Medical College Journal. 4 (1): 30–36. doi:10.3329/akmmcj.v4i1.13682. ISSN 2304-5701.

- ^ Image by Mikael Häggström, using following source image: Figure 1 - available via license: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International", from the following article:

Sitnik, Roberta; Torres, Margareth Afonso; Strachman Bacal, Nydia; Pinho, João Renato Rebello (2006). "Using PCR for molecular monitoring of post-transplantation chimerism". Einstein (Sao Paulo). 4 (2). S2CID 204763685. - ^ "Combined DNA Index System (CODIS)". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Curtis C, Hereward J (29 August 2017). "From the crime scene to the courtroom: the journey of a DNA sample". The Conversastion. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ^ Felch J, et al. (20 July 2008). "FBI resists scrutiny of 'matches'". Los Angeles Times. pp. P8. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- ^ "Y haplotype reference database". Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Ravikumar D, Gurunathan D, Gayathri R, Priya VV, Geetha RV (1 January 2018). "DNA profiling of Streptococcus mutans in children with and without black tooth stains: A polymerase chain reaction analysis". Dental Research Journal. 15 (5): 334–339. doi:10.4103/1735-3327.240472. PMC 6134728. PMID 30233653.

- ^ Kashyap, V. K. (8 February 2004). "DNA Profiling Technologies in Forensic Analysis". International Journal of Human Genetics. 4 (1). doi:10.31901/24566330.2004/04.01.02.

- ^ Bieber FR, Buckleton JS, Budowle B, Butler JM, Coble MD (August 2016). "Evaluation of forensic DNA mixture evidence: protocol for evaluation, interpretation, and statistical calculations using the combined probability of inclusion". BMC Genetics. 17 (1) 125. doi:10.1186/s12863-016-0429-7. PMC 5007818. PMID 27580588.

- ^ a b Butler J (2001). "Chapter 7". Forensic DNA Typing. Academic Press. pp. 99–115.

- ^ Butler, John M. (2005). Forensic DNA typing : biology, technology, and genetics of STR markers (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press. pp. 68, 167–168. ISBN 978-0-12-147952-7.

- ^ Butler, John M. (2015). Advanced topics in forensic DNA typing : interpretation. Oxford, England: Academic Press. pp. 159–161. ISBN 978-0-12-405213-0.

- ^ Gittelson, S; Steffen, CR; Coble, MD (July 2016). "Low-template DNA: A single DNA analysis or two replicates?". Forensic Science International. 264: 139–45. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.04.012. PMC 5225751. PMID 27131143.

- ^ a b Coble MD, Butler JM (January 2005). "Characterization of new miniSTR loci to aid analysis of degraded DNA". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 50 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1520/JFS2004216. PMID 15830996.

- ^ Whitaker JP, Clayton TM, Urquhart AJ, Millican ES, Downes TJ, Kimpton CP, Gill P (April 1995). "Short tandem repeat typing of bodies from a mass disaster: high success rate and characteristic amplification patterns in highly degraded samples". BioTechniques. 18 (4): 670–677. PMID 7598902.

- ^ Weir BS, Triggs CM, Starling L, Stowell LI, Walsh KA, Buckleton J (March 1997). "Interpreting DNA mixtures". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 42 (2): 213–222. doi:10.1520/JFS14100J. PMID 9068179.

- ^ Butler, John M. (2015). Advanced topics in forensic DNA typing : interpretation. Oxford, England: Academic Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-12-405213-0.

- ^ Butler, John M. (2015). Advanced topics in forensic DNA typing : interpretation. Oxford, England: Academic Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-12-405213-0.

- ^ "Tri-Allelic Patterns". strbase.nist.gov. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Butler J (2001). "Chapter 7". Forensic DNA Typing. Academic Press. pp. 99–119.

- ^ Indiana State Police Laboratory. "Introduction to STRmix and Likelifood Ratios" (PDF). In.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 25 October 2018.

- ^ "Plant DNA fingerprinting: an overview".

- ^ a b "Application of DNA Fingerprinting for Plant Identification" (PDF).

- ^ "DNA fingerprinting in Agricultural Genetics Programs". Archived from the original on 10 December 2023. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ Miller K. "Mitochondrial DNA Concordance". University of Cambridge – Biological Anthropology. Archived from the original on 22 January 2003.

- ^ Miller KW, Dawson JL, Hagelberg E (1996). "A concordance of nucleotide substitutions in the first and second hypervariable segments of the human mtDNA control region". International Journal of Legal Medicine. 109 (3): 107–113. doi:10.1007/bf01369668. PMID 8956982.

- ^ "CODIS – National DNA Index System". Fbi.gov. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ "Restrictions on use and destruction of fingerprints and samples". Wikicrimeline.co.uk. 1 September 2009. Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ Curtis C, Hereward J, Mangelsdorf M, Hussey K, Devereux J (July 2019). "Protecting trust in medical genetics in the new era of forensics" (PDF). Genetics in Medicine. 21 (7): 1483–1485. doi:10.1038/s41436-018-0396-7. PMC 6752261. PMID 30559376. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ Price-Livingston S (5 June 2003). "DNA Testing Provisions in Patriot Act". Connecticut General Assembly. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ Goos L, Rose JD. DNA: A Practical Guide. Toronto: Carswell Publications. Archived from the original on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Cole, Simon A (1 August 2007). "Double Helix Jeopardy". IEEE Spectrum.

- ^ "Congress OKs bill to cut rape evidence backlog". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ Jiang, Bin; Zhao, Yikun; Yi, Hongmei; Huo, Yongxue; Wu, Haotian; Ren, Jie; Ge, Jianrong; Zhao, Jiuran; Wang, Fengge (30 March 2020). "PIDS: A User-Friendly Plant DNA Fingerprint Database Management System". Genes. 11 (4): 373. doi:10.3390/genes11040373. PMC 7230844. PMID 32235513.

- ^ Schiller J (2010). Genome Mapping to Determine Disease Susceptibility. CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1453735435.

- ^ Walsh NP (27 January 2002). "False result fear over DNA tests". The Observer. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021.

- ^ National Research Council (US) Committee on DNA Forensic Science: An Update (1996). The evaluation of forensic DNA evidence. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. doi:10.17226/5141. ISBN 978-0309053952. PMID 25121324. Archived from the original on 30 August 2008.

- ^ "Two Women Don't Match Their Kids' DNA". Abcnews.go.com. 15 August 2006. Archived from the original on 28 October 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ Hartley JL, Temple GF, Brasch MA (November 2000). "DNA cloning using in vitro site-specific recombination". Genome Research. 10 (11): 1788–1795. doi:10.1101/gr.143000. PMC 310948. PMID 11076863.

- ^ Diamond D (12 April 2011). "Searching the Family DNA Tree to Solve Crime". HuffPost Denver (Blog). The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 14 April 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Bieber FR, Brenner CH, Lazer D (June 2006). "Human genetics. Finding criminals through DNA of their relatives". Science. 312 (5778): 1315–1316. doi:10.1126/science.1122655. PMID 16690817.

- ^ Staff. "Familial searches allows law enforcement to identify criminals through their family members". DNA Forensics. United Kingdom – A Pioneer in Familial Searches. Archived from the original on 7 November 2010. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ^ Bhattacharya S (20 April 2004). "Killer convicted thanks to relative's DNA". Daily News. New Scientist. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Greely, Henry T.; Riordan, Daniel P.; Garrison, Nanibaa' A.; Mountain, Joanna L. (2006). "Family Ties: The Use of DNA Offender Databases to Catch Offenders' Kin". Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 34 (2): 248–262. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720X.2006.00031.x. PMID 16789947.

- ^ a b Pankratz H (17 April 2011). "Denver Uses 'Familial DNA Evidence' to Solve Car Break-Ins". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012.

- ^ Steinhaur J (9 July 2010). "Grim Sleeper' Arrest Fans Debate on DNA Use". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Dolan M. "A New Track in DNA Search" (PDF). LA Times. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ "New DNA Technique Led Police to 'Grim Sleeper' Serial Killer and Will 'Change Policing in America". ABC News. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020.

- ^ Dolan M (15 March 2011). "Familial DNA Search Used In Grim Sleeper Case Leads to Arrest of Santa Cruz Sex Offender". LA Times. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Helderman R. "McDonnell Approves Familial DNA for VA Crime Fighting". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ^ Christoffersen J, Barakat M. "Other victims of East Coast Rapist suspect sought". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2011.

- ^ Murphy EA (2009). "Relative Doubt: Familial Searches of DNA Databases" (PDF). Michigan Law Review. 109: 291–348. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 December 2010.

- ^ Suter S (2010). "All in The Family: Privacy and DNA Familial Searching" (PDF). Harvard Journal of Law and Technology. 23: 328. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011.

- ^ Kaye, David H (2013). "The Genealogy Detectives: A Constitutional Analysis of 'Familial Searching'". American Criminal Law Review. 51 (1): 109–163. SSRN 2043091.

- ^ "US v. Pool" (PDF). Pool 621F .3d 1213. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 April 2011.

- ^ "Finding Criminals Through DNA Testing of Their Relatives" Technical Bulletin, Chromosomal Laboratories, Inc. accessed 22 April 2011.

- ^ "Denver District Attorney DNA Resources". Archived from the original on 24 March 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ "Darryl Hunt". The Innocence Project. Archived from the original on 28 August 2007.

- ^ Easteal PW, Easteal S (3 November 2017). "The forensic use of DNA profiling". Australian Institute of Criminology. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ Harmon A (3 April 2008). "Lawyers Fight DNA Samples Gained on Sly". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Supreme Court allows DNA sampling of prisoners". UPI. Archived from the original on 10 June 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ^ "Supreme Court of the United States – Syllabus: Maryland v. King, Certiorari to the Court of Appeals of Maryland" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ Samuels JE, Davies EH, Pope DB (June 2013). Collecting DNA at Arrest: Policies, Practices, and Implications (PDF). Justice Policy Center (Report). Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2015.

- ^ "Human Tissue Act 2004". UK. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- ^ R v. Loveridge, EWCA Crim 734 (2001).

- ^ R v. Doheny [1996] EWCA Crim 728, [1997] 1 Cr App R 369 (31 July 1996), Court of Appeal

- ^ R v. Adams [1997] EWCA Crim 2474 (16 October 1997), Court of Appeal

- ^ R v Bates [2006] EWCA Crim 1395 (7 July 2006), Court of Appeal

- ^ "WikiCrimeLine DNA profiling". Wikicrimeline.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 October 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ "Genelex: The DNA Paternity Testing Site". Healthanddna.com. 6 January 1996. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ "Forensic Science Database: Search By State". NCSL.org. Archived from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d Pollack A (18 August 2009). "DNA Evidence Can Be Fabricated, Scientists Show". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ Rana AK (2018). "Crime investigation through DNA methylation analysis: Methods and applications in forensics". Egyptian Journal of Forensic Sciences. 8 7. doi:10.1186/s41935-018-0042-1.

- ^ Frumkin D, Wasserstrom A, Davidson A, Grafit A (February 2010). "Authentication of forensic DNA samples". Forensic Science International. Genetics. 4 (2): 95–103. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.179.2718. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2009.06.009. PMID 20129467. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ a b Genomics, Front Line; Mobley, Immy (22 November 2021). "Is the use of artificial genomic DNA the future? - Front Line Genomics". Front Line Genomics - Delivering the Benefits of Genomics to Patients Faster. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ Patel, Sahishnu; Jung, Dongju; Yin, Perry T.; Carlton, Peter; Yamamoto, Makoto; Bando, Toshikazu; Sugiyama, Hiroshi; Lee, Ki-Bum (20 August 2014). "NanoScript: A Nanoparticle-Based Artificial Transcription Factor for Effective Gene Regulation". ACS Nano. 8 (9): 8959–8967. doi:10.1021/nn501589f. PMC 4174092. PMID 25133310.

- ^ Qi, Hao; Huang, Guoyou; Han, Yulong; Zhang, Xiaohui; Li, Yuhui; Pingguan-Murphy, Belinda; Lu, Tian Jian; Xu, Feng; Wang, Lin (1 June 2015). "Engineering Artificial Machines from Designable DNA Materials for Biomedical Applications". Tissue Engineering. Part B, Reviews. 21 (3): 288–297. doi:10.1089/ten.teb.2014.0494. PMC 4442581. PMID 25547514.

- ^ "DNA pioneer's 'eureka' moment". BBC News. 9 September 2009. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ Joseph Wambaugh, The Blooding (New York, New York: A Perigord Press Book, 1989), 369.

- ^ Joseph Wambaugh, The Blooding (New York, New York: A Perigord Press Book, 1989), 316.

- ^ "Gene Technology". Txtwriter.com. 6 November 1987. p. 14. Archived from the original on 27 November 2002. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ "frontline: the case for innocence: the dna revolution: state and federal dna database laws examined". Pbs.org. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ "Jak usvědčit vraha omilostněného prezidentem?" (in Czech). Czech Radio. 29 January 2020. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Jedlička M. "Milan Lubas – a sex aggressor and murderer". Translated by Vršovský P. Kriminalistika.eu. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Court of Appeals of Arizona: Denial of Bogan's motion to reverse his conviction and sentence" (PDF). Denver DA: www.denverda.org. 11 April 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ "DNA Forensics: Angiosperm Witness for the Prosecution". Human Genome Project. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ "Crime Scene Botanicals". Botanical Society of America. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ Gill P, Ivanov PL, Kimpton C, Piercy R, Benson N, Tully G, et al. (February 1994). "Identification of the remains of the Romanov family by DNA analysis". Nature Genetics. 6 (2): 130–135. doi:10.1038/ng0294-130. PMID 8162066.

- ^ a b Murnaghan I (28 December 2012). "Famous Trials and DNA Testing; Earl Washington Jr". Explore DNA. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Jeffries S (8 October 2006). "Suspect Nation". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ "Frank Lee Smith". The University of Michigan Law School, National Registry of Exonerations. June 2012. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Stephen G (17 February 2008). "Freedom in bag for killer Graham?". Belfasttelegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 October 2012. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- ^ Dutter B (19 June 2001). "18 years on, man is jailed for murder of Briton in 'paradise'". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ^ McCutcheon P (8 September 2004). "DNA evidence may not be infallible: experts". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 11 February 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ^ Joshua Rozenberg,"DNA proves Hanratty guilt 'beyond doubt'", Daily Telegraph, London, 11 May 2002.

- ^ Steele (23 June 2001). "Hanratty lawyers reject DNA 'guilt'". Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 11 October 2018.

- ^ "Hanratty: The damning DNA". BBC News. 10 May 2002. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ^ "Mistaken identity claim over murder". BBC News. 15 February 2003. Archived from the original on 21 August 2017. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ Sekar S. "Lynette White Case: How Forensics Caught the Cellophane Man". Lifeloom.com. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ "Dennis Halstead". The National Registry of Exonerations, University of Michigan Law School. 18 April 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ^ Breed AG (5 May 2004). "DNA clears man of 1914 kidnapping conviction". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012.

- ^ "Jane Mixer murder case". CBS News. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ "challenging Leiterman's conviction in the Mixer murder". www.garyisinnocent.org. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016.

- ^ Doughery P. "D.B. Tuber". History Link. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ^ Booth J. "Police name David Lace as true killer of Teresa De Simone". The Times. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ "Who Was She? A DNA Test Opened Up New Mysteries". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 6 June 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ "I thought I was Irish – until I did a DNA test". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ "Who were my parents – and why was I left on a hillside to die?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ "Living DNA provide closure on lifetime search for biological father". Living DNA. 19 March 2018. Archived from the original on 10 April 2018. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ ""Buckskin Girl" case: DNA breakthrough leads to ID of 1981 murder victim". CBS News. 12 April 2018. Archived from the original on 22 June 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ Zhang S (17 April 2018). "How a Genealogy Website Led to the Alleged Golden State Killer". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ^ Michaeli Y (16 November 2018). "To Solve Cold Cases, All It Takes Is Crime Scene DNA, a Genealogy Site and High-speed Internet". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Fingerprint Technology Helps Solve Cold Case". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ "Judgment In the matter of the Baronetcy of Pringle of Stichill" (PDF). 20 June 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Kaye DH (2010). The Double Helix and the Law of Evidence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674035881. OCLC 318876881.

- Koerner BI (13 October 2015). "Family Ties: Your Relatives' DNA Could Turn You Into a Suspect" (paper). Wired. pp. 35–38. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Dunning, Brian (1 March 2022). "Skeptoid #821: Forensic (Pseudo) Science". Skeptoid. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

External links

[edit]- McKie R (24 May 2009). "Eureka moment that led to the discovery of DNA fingerprinting". The Observer. London.

- Forensic Science, Statistics, and the Law – Blog that tracks scientific and legal developments pertinent to forensic DNA profiling

- Create a DNA Fingerprint – PBS.org

- In silico simulation of Molecular Biology Techniques – A place to learn typing techniques by simulating them

- National DNA Databases in the EU

- The Innocence Record Archived 13 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Winston & Strawn LLP/The Innocence Project

- Making Sense of DNA Backlogs, 2012: Myths vs. Reality United States Department of Justice

- "Making Sense of Forensic Genetics". Sense about Science. 25 January 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

DNA profiling

View on GrokipediaHistory

Invention and Early Development

British geneticist Alec Jeffreys developed the technique of DNA fingerprinting in 1984 at the University of Leicester's Department of Genetics.[2] Jeffreys had been investigating DNA sequence variation since the late 1970s, focusing on minisatellite regions—stretches of DNA with tandem repeats that vary greatly in length among individuals.[11] On September 10, 1984, while developing a new DNA probe for studying genetic mutations related to hereditary diseases, Jeffreys observed highly variable band patterns on an autoradiograph, leading to the realization that these patterns could serve as unique genetic identifiers for individuals, excluding identical twins.[12] The initial method relied on restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, involving the digestion of genomic DNA with restriction enzymes, separation of fragments by agarose gel electrophoresis, Southern blotting, and hybridization with radiolabeled minisatellite probes to produce a barcode-like pattern of bands.[13] This approach exploited the hypervariability of minisatellite loci, where differences in repeat copy numbers created distinguishable fragment lengths.[14] Jeffreys and his team, including colleagues Alec Wainwright and Ruth Charles, refined the technique over the following months, demonstrating its potential for applications beyond mutation detection.[13] Early validation occurred in 1985 when the method was applied to resolve an immigration dispute in the United Kingdom, confirming the biological relationship between a British woman and her alleged half-sister from Ghana through DNA pattern matching.[3] This non-forensic use marked the first practical implementation of DNA profiling, highlighting its reliability for kinship determination with match probabilities exceeding one in a million.[11] The technique's forensic potential was soon recognized, paving the way for its adoption in criminal investigations by 1986.[15]Initial Forensic Applications

The first forensic application of DNA profiling occurred in 1986 in the United Kingdom, during the investigation of the murders of Lynda Mann in 1983 and Dawn Ashworth in 1986 in Narborough, Leicestershire.[11] British police consulted geneticist Alec Jeffreys, who had developed DNA fingerprinting using restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis in 1984, to analyze semen samples from the crime scenes.[16] This marked the debut of DNA evidence in a criminal case, initially exonerating suspect Richard Buckland, whose DNA profile did not match the samples, representing the first use of the technique to clear an innocent individual.[17] Subsequent application involved systematic screening of approximately 5,000 local males to generate DNA profiles for comparison against the crime scene evidence.[11] Colin Pitchfork, the perpetrator, attempted evasion by persuading a colleague to submit a blood sample in his place, but discrepancies in the screening process led to his identification when the substitute's sample mismatched and prompted further scrutiny.[18] Pitchfork's DNA profile matched the crime scene samples, leading to his arrest in 1987 and conviction in January 1988 for the rapes and murders, establishing DNA profiling as a pivotal tool in forensic identification.[19] Early forensic DNA applications relied on RFLP, which required substantial quantities of high-quality DNA (typically 50-100 ng) from sources like blood or semen, limiting its use to cases with well-preserved evidence.[20] The technique's specificity, leveraging variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs), yielded highly discriminatory profiles, with match probabilities often exceeding one in a million, though initial implementations faced challenges in standardization and court admissibility due to novelty.[21] This case spurred global adoption, influencing subsequent investigations and prompting the development of forensic DNA databases.[15]Evolution into Standard Practice