Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Laser printing

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on the |

| History of printing |

|---|

|

Laser printing is an electrostatic digital printing process. It produces high-quality text and graphics (and moderate-quality photographs) by repeatedly passing a laser beam back and forth over a negatively charged cylinder called a "drum" to define a differentially charged image.[1] The drum then selectively collects electrically charged powdered ink (toner), and transfers the image to paper, which is then heated to permanently fuse the text, imagery, or both to the paper. As with digital photocopiers, laser printers employ a xerographic printing process. Laser printing differs from traditional xerography as implemented in analog photocopiers in that in the latter, the image is formed by reflecting light off an existing document onto the exposed drum.

The laser printer was invented at Xerox PARC in the 1970s. Laser printers were introduced for the office and then home markets in subsequent years by IBM, Canon, Xerox, Apple, Hewlett-Packard and many others. Over the decades, quality and speed have increased as prices have decreased, and the once cutting-edge printing devices are now ubiquitous.

History

[edit]

In the 1960s, the Xerox Corporation held a dominant position in the photocopier market.[2] In 1969, Gary Starkweather, who worked in Xerox's product development department, had the idea of using a laser beam to "draw" an image of what was to be copied directly onto the copier drum. After transferring to the recently formed Palo Alto Research Center (Xerox PARC) in 1971, Starkweather adapted a Xerox 7000 copier to make SLOT (Scanned Laser Output Terminal). In 1972, Starkweather worked with Butler Lampson and Ronald Rider to add a control system and character generator, resulting in a printer called EARS (Ethernet, Alto Research character generator, Scanned laser output terminal)—which later became the Xerox 9700 laser printer.[3][4][5] In 1976, the first commercial implementation of a laser printer, the IBM 3800, was released. It was designed for data centers, where it replaced line printers attached to mainframe computers. The IBM 3800 was used for high-volume printing on continuous stationery, and achieved speeds of 215 pages per minute (ppm), at a resolution of 240 dots per inch (dpi). Over 8,000 of these printers were sold.[6]

Soon after, in 1977, the Xerox 9700 was brought to market. Unlike the IBM 3800, the Xerox 9700 was not targeted to replace any particular existing printers; however, it did have limited support for the loading of fonts. The Xerox 9700 excelled at printing high-value documents on cut-sheet paper with varying content (e.g., insurance policies).[6] Inspired by the Xerox 9700's commercial success, Japanese camera and optics company Canon developed in 1979 the Canon LBP-10, a low-cost desktop laser printer. Canon then began work on a much-improved print engine, the Canon CX, resulting in the LBP-CX printer. Having no experience in selling to computer users, Canon sought partnerships with three Silicon Valley companies: Diablo Data Systems (who rejected the offer), Hewlett-Packard (HP), and Apple Computer.[7][8]

In 1981, the first small personal computer designed for office use, the Xerox Star 8010, reached market. The system used a desktop metaphor that was unsurpassed in commercial sales, until the Apple Macintosh. Although it was innovative, the Star workstation was a prohibitively expensive (US$17,000) system, affordable only to a fraction of the businesses and institutions at which it was targeted.[9] Later, in 1984, the first laser printer intended for mass-market sales, the HP LaserJet, was released; it used the Canon CX engine, controlled by HP software[10]: 5–8 . The LaserJet was quickly followed by printers from Brother Industries, IBM, and others. First-generation machines had large photosensitive drums, of circumference greater than the loaded paper's length. Once faster-recovery coatings were developed, the drums could touch the paper multiple times in a pass, and therefore be smaller in diameter. A year later, Apple introduced the LaserWriter (also based on the Canon CX engine),[11] but used the newly released PostScript page-description language (up until this point, each manufacturer used its own proprietary page-description language, making the supporting software complex and expensive). PostScript allowed the use of text, fonts, graphics, images, and color largely independent of the printer's brand or resolution. PageMaker, developed by Aldus for the Macintosh and LaserWriter, was also released in 1985 and the combination became very popular for desktop publishing.[5][6] Laser printers brought exceptionally fast and high-quality text printing in multiple fonts on a page, to the business and home markets. No other commonly available printer during this era could also offer this combination of features.[citation needed]

Printing process

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2020) |

A laser beam projects an image of the page to be printed onto an electrically charged, photoconductive, rotating, cylindrical drum.[12] Photoconductivity conducts charged electrons away from the areas exposed to laser light. Powdered ink (toner) particles are then electrostatically attracted to remaining areas of the drum that have not been laser-beamed.

The drum then transfers the image onto paper which is passed through the machine by direct contact. Finally, the paper is passed onto a finisher, which uses heat to instantly fuse the toner that represents the image onto the paper.

The laser is typically an aluminium gallium arsenide (AlGaAs) semiconductor laser, which emits red or infrared light.

The drum is coated with selenium, or more recently, with an organic photoconductor made of N-vinylcarbazole, an organic monomer.

There are typically seven steps involved in the process, detailed in the sections below.

Raster image processing

[edit]The document to be printed is encoded in a page description language such as PostScript, Printer Command Language (PCL), or Open XML Paper Specification (OpenXPS). The raster image processor (RIP) converts the page description into a bitmap which is stored in the printer's raster memory. Each horizontal strip of dots across the page is known as a raster line or scan line.

Laser printing differs from other printing technologies in that each page is always rendered in a single continuous process without any pausing in the middle, while other technologies like inkjet can pause every few lines.[13] To avoid a buffer underrun (where the laser reaches a point on the page before it has the dots to draw there), a laser printer typically needs enough raster memory to hold the bitmap image of an entire page.

Memory requirements increase with the square of the dots per inch, so 600 dpi requires a minimum of 4 megabytes for monochrome, and 16 megabytes for color (still at 600 dpi). For fully graphical output using a page description language, a minimum of 1 megabyte of memory is needed to store an entire monochrome letter- or A4-sized page of dots at 300 dpi. At 300 dpi, there are 90,000 dots per square inch (300 dots per linear inch). A typical 8.5 × 11 sheet of paper has 0.25-inch (6.4 mm) margins, reducing the printable area to 8.0 by 10.5 inches (200 mm × 270 mm), or 84 square inches. 84 sq/in × 90,000 dots per sq/in = 7,560,000 dots. 1 megabyte = 1,048,576 bytes, or 8,388,608 bits, which is just large enough to hold the entire page at 300 dpi, leaving about 100 kilobytes to spare for use by the raster image processor.

In a color printer, each of the four CMYK toner layers is stored as a separate bitmap, and all four layers are typically preprocessed before printing begins, so a minimum of 4 megabytes is needed for a full-color letter-size or A4-size page at 300 dpi.

During the 1980s, memory chips were still very expensive, which is why entry-level laser printers in that era always came with four-digit suggested retail prices in US dollars. The primitive microprocessors in early personal computers were so underpowered and insufficient for graphics work that attached laser printers usually had more onboard processing power.[14] Memory prices later decreased significantly, while rapid improvements in the performance of PCs and peripheral cables (most importantly, SCSI) enabled the development of low-end laser printers which offload rasterization to the sending PC. For such printers, the operating system's print spooler renders the raw bitmap of each page into the PC's system memory at the target resolution, then sends that bitmap directly to the laser (at the expense of slowing down all other programs on the sending PC).[15] The appearance of so-called "dumb" or "host-based" laser printers from NEC made it possible for the retail cost of low-end 300-dpi laser printers to decrease to as low as US$700 by early 1994[16] and US$600 by early 1995.[17] In September 1997, HP introduced the host-based LaserJet 6L, which could print 600 dpi text at up to six pages per minute for only US$400.[18]

1200 dpi printers have been widely available in the home market since 2008. 2400 dpi electrophotographic printing plate makers, essentially laser printers that print on plastic sheets, are also available.

Charging

[edit]

In older printers, a corona wire positioned parallel to the drum or, in more recent printers, a primary charge roller, projects an electrostatic charge onto the photoreceptor (otherwise named the photoconductor unit), a revolving photosensitive drum or belt, which is capable of holding an electrostatic charge on its surface while it is in the dark.

An AC bias voltage is applied to the primary charge roller to remove any residual charges left by previous images. The roller will also apply a DC bias on the drum surface to ensure a uniform negative potential.

Numerous patents[specify] describe the photosensitive drum coating as a silicon "sandwich" with a photocharging layer, a charge leakage barrier layer, as well as a surface layer. One version[specify] uses amorphous silicon containing hydrogen as the light-receiving layer, boron nitride as a charge leakage barrier layer, as well as a surface layer of doped silicon, notably silicon with oxygen or nitrogen which at sufficient concentration resembles machining silicon nitride.

Exposing

[edit]

A laser printer uses a laser because lasers are able to form highly focused, precise, and intense beams of light, especially over the short distances inside of a printer. The laser is aimed at a rotating polygonal mirror which directs the light beam through a system of lenses and mirrors onto the photoreceptor drum, writing pixels at rates up to sixty-five million times per second.[19] The drum continues to rotate during the sweep, and the angle of sweep is canted very slightly to compensate for this motion. The stream of rasterized data held in the printer's memory rapidly turns the laser on and off as it sweeps.

The laser beam neutralizes (or reverses) the charge on the surface of the drum, leaving a static electric negative image on the drum's surface which will repel the negatively charged toner particles. The areas on the drum which were struck by the laser, however, momentarily have no charge, and the toner being pressed against the drum by the toner-coated developer roll in the next step moves from the roll's rubber surface to the charged portions of the surface of the drum.[20][21]

Some non-laser printers (LED printers) use an array of light-emitting diodes spanning the width of the page to generate an image, rather than using a laser. "Exposing" is also known as "writing" in some documentation.

Developing

[edit]As the drums rotate, toner is continuously applied in a 15-micron-thick layer to the developer roll. The surface of the photoreceptor with the latent image is exposed to the toner-covered developer roll.

Toner consists of fine particles of dry plastic powder mixed with carbon black or coloring agents. The toner particles are given a negative charge inside the toner cartridge, and as they emerge onto the developer drum they are electrostatically attracted to the photoreceptor's latent image (the areas on the surface of the drum which had been struck by the laser). Because negative charges repel each other, the negatively charged toner particles will not adhere to the drum where the negative charge (imparted previously by the charge roller) remains.

Transferring

[edit]A sheet of paper is then rolled under the photoreceptor drum, which has been coated with a pattern of toner particles in the exact places where the laser struck it moments before. The toner particles have a very weak attraction to both the drum and the paper, but the bond to the drum is weaker and the particles transfer once again, this time from the drum's surface to the paper's surface. Some machines also use a positively charged "transfer roller" on the backside of the paper to help pull the negatively charged toner from the photoreceptor drum to the paper.

Fusing

[edit]

The paper passes through rollers in the fuser assembly, where temperatures up to 427 °C (801 °F) and pressure are used to permanently bond the toner to the paper. One roller is usually a hollow tube (heat roller) and the other is a rubber-backed roller (pressure roller). A radiant heat lamp is suspended in the center of the hollow tube, and its infrared energy uniformly heats the roller from the inside. For proper bonding of the toner, the fuser roller must be uniformly hot.

Some printers use a very thin flexible metal foil roller, so there is less thermal mass to be heated and the fuser can more quickly reach operating temperature. If paper moves through the fuser more slowly, there is more roller contact time for the toner to melt, and the fuser can operate at a lower temperature. Smaller, inexpensive laser printers typically print slowly, due to this energy-saving design, compared to large high-speed printers where paper moves more rapidly through a high-temperature fuser with very short contact time.

Cleaning and recharging

[edit]

As the drum completes a revolution, it is exposed to an electrically neutral soft plastic blade that cleans any remaining toner from the photoreceptor drum and deposits it into a waste reservoir. A charge roller then re-establishes a uniform negative charge on the surface of the now-clean drum, readying it to be struck again by the laser.

Continuous printing

[edit]Once the raster image generation is complete, all steps of the printing process can occur one after the other in rapid succession. This permits the use of a very small and compact unit, where the photoreceptor is charged, rotates a few degrees and is scanned, rotates a few more degrees, and is developed, and so forth. The entire process can be completed before the drum completes one revolution.

Different printers implement these steps in distinct ways. LED printers use a linear array of light-emitting diodes to "write" the light on the drum. The toner is based on either wax or plastic, so that when the paper passes through the fuser assembly, the particles of toner melt. The paper may or may not be oppositely charged. The fuser can be an infrared oven, a heated pressure roller, or (on some very fast, expensive printers) a xenon flash lamp. The warmup process that a laser printer goes through when power is initially applied to the printer consists mainly of heating the fuser element.

Malfunctions

[edit]

The mechanism inside a laser printer is somewhat delicate and, once damaged, often impossible to repair. The drum, in particular, is a critical component: it must not be left exposed to ambient light for more than a few hours, as light is what causes it to lose its charge and will eventually wear it out. Anything that interferes with the operation of the laser such as a scrap of torn paper may prevent the laser from discharging some portion of the drum, causing those areas to appear as white vertical streaks. If the neutral wiper blade fails to remove residual toner from the drum's surface, that toner may circulate on the drum a second time, causing smears on the printed page with each revolution. If the charge roller becomes damaged or does not have enough power, it may fail to adequately negatively charge the surface of the drum, allowing the drum to pick up excessive toner on the next revolution from the developer roll and causing a repeated but fainter image from the previous revolution to appear down the page.

If the toner doctor blade does not ensure that a smooth, even layer of toner is applied to the developer roll, the resulting printout may have white streaks from this in places where the blade has scraped off too much toner. Alternatively, if the blade allows too much toner to remain on the developer roll, the toner particles might come loose as the roll turns, precipitate onto the paper below, and become bonded to the paper during the fusing process. This will result in a general darkening of the printed page in broad vertical stripes with very soft edges.

If the fuser roller does not reach a high enough temperature or if the ambient humidity is too high, the toner will not fuse well to the paper and may flake off after printing. If the fuser is too hot, the plastic component of the toner may smear, causing the printed text to look like it is wet or smudged, or may cause the melted toner to soak through the paper to the backside.

Different manufacturers claim that their toners are specifically developed for their printers and that other toner formulations may not match the original specifications in terms of either tendency to accept a negative charge, to move to the discharged areas of the photoreceptor drum from the developer roll, to fuse appropriately to the paper, or to come off the drum cleanly in each revolution.[citation needed]

Performance

[edit]As with most electronic devices, the cost of laser printers has decreased significantly over the years. In 1984, the HP LaserJet sold for $3500,[22] had trouble with even small, low-resolution graphics, and weighed 32 kg (71 lb). By the late 1990s, monochrome laser printers had become inexpensive enough for home-office use, having displaced other printing technologies, although color inkjet printers (see below) still had advantages in photo quality reproduction. As of 2016[update], low-end monochrome laser printers can sell for less than $75, and while these printers tend to lack onboard processing and rely on the host computer to generate a raster image, they nonetheless outperform the 1984 LaserJet in nearly all situations.

Laser printer speed can vary widely, and depends on many factors, including the graphic intensity of the job being processed. The fastest models can print over 200 monochrome pages per minute (12,000 pages per hour). The fastest color laser printers can print over 100 pages per minute (6000 pages per hour). Very high-speed laser printers are used for mass mailings of personalized documents, such as credit card or utility bills, and are competing with lithography in some commercial applications.[23]

The cost of this technology depends on a combination of factors, including the cost of paper, toner, drum replacement, as well as the replacement of other items such as the fuser assembly and transfer assembly. Often printers with soft plastic drums can have a very high cost of ownership that does not become apparent until the drum requires replacement.

Duplex printing (printing on both sides of the paper) can halve paper costs and reduce filing volumes, albeit at a slower page-printing speed because of the longer paper path. Formerly only available on high-end printers, duplexers are now common on mid-range office printers, though not all printers can accommodate a duplexing unit.

In a commercial environment such as an office, it is becoming increasingly common for businesses to use external software that increases the performance and efficiency of laser printers in the workplace. The software can be used to set rules dictating how employees interact with printers, such as setting limits on how many pages can be printed per day, limiting usage of color ink, and flagging jobs that appear to be wasteful.[24]

Color laser printers

[edit]

Color laser printers use colored toner (dry ink), typically cyan, magenta, yellow, and black (CMYK). While monochrome printers only use one laser scanner assembly, color printers often have two or more, often one for each of the four colors.

Color printing adds complexity to the printing process because very slight misalignments known as registration errors can occur between printing each color, causing unintended color fringing, blurring, or light/dark streaking along the edges of colored regions. To permit a high registration accuracy, some color laser printers use a large rotating belt called a "transfer belt". The transfer belt passes in front of all the toner cartridges and each of the toner layers are precisely applied to the belt. The combined layers are then applied to the paper in a uniform single step.

Color printers usually have a higher cost per page than monochrome printers, even if printing monochrome-only pages.

Liquid electrophotography (LEP) is a similar process used in HP Indigo presses that uses electrostatically charged ink instead of toner, and using a heated transfer roller instead of a fuser, that melts the charged ink particles before applying them to the paper.

Color laser transfer printers

[edit]Color laser transfer printers are designed to produce transfer media which are transfer sheets designed to be applied by means of a heat press. These transfers are typically used to make custom T-shirts or custom logo products with corporate or team logos on them.

2-part Color laser transfers are part of a two-step process whereby the color laser printers use colored toner (dry ink), typically cyan, magenta, yellow, and black (CMYK); however, newer printers designed to print on dark T-shirts utilize a special white toner allowing them to make transfers for dark garments or dark business products.

The CMYK color printing process allows for millions of colors to be faithfully represented by the unique imaging process.

Business-model comparison with inkjet printers

[edit]Manufacturers use a similar business model for both low-cost color laser printers and inkjet printers: the printers are sold cheaply while replacement toners and inks are relatively expensive. A color laser printer's average running cost per page is usually slightly less, even though both the laser printer and laser toner cartridge have higher upfront prices, as laser toner cartridges print many more sheets relative to their cost than inkjet cartridges.[25][26]

The print quality of color lasers is limited by their resolution (typically 600–1200 dpi) and their use of just four color toners. They often have trouble printing large areas of the same or subtle gradations of color. Inkjet printers designed for printing photos can produce much higher quality color images.[27] An in-depth comparison of inkjet and laser printers suggest that laser printers are the ideal choice for a high quality, volume printer, while inkjet printers tend to focus on large-format printers and household units. Laser printers offer more precise edging and in-depth monochromatic color. In addition, color laser printers are much faster than inkjet printers, although being generally larger and bulkier.[28]

Anti-counterfeiting marks

[edit]

Many modern color laser printers mark printouts by a nearly invisible dot raster, for the purpose of traceability. The dots are yellow and about 0.1 mm (0.0039 in) in size, with a raster of about 1 mm (0.039 in). This is purportedly the result of a deal between the US government and printer manufacturers to help track counterfeiters.[29] The dots encode data such as printing date, time, and printer serial number in binary-coded decimal on every sheet of paper printed, which allows pieces of paper to be traced by the manufacturer to identify the place of purchase, and sometimes the buyer.

Digital-rights advocacy groups such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation are concerned about this erosion of the privacy and anonymity of those who print.[30] In particular, the tracking dots were implicated as a tool that directly lead to the arrest and conviction of whistleblower Reality Winner.[31][32]

Smart chips in toner cartridges

[edit]Similar to inkjet printers, toner cartridges may contain smart chips that reduce the number of pages that can be printed with it (reducing the amount of usable ink or toner in the cartridge to sometimes only 50%[33]), in an effort to increase sales of the toner cartridges.[34] Besides being more expensive for printer users, this technique also increases waste, and thus increases pressure on the environment. For these toner cartridges (as with inkjet cartridges), reset devices can be used to override the limitation set by the smart chip. Also, for some printers, online walk-throughs have been posted to demonstrate how to use up all the ink in the cartridge.[35] These chips offer no benefit to the end-user—some laser printers used an optical mechanism to assess the amount of remaining toner in the cartridge rather than using a chip to electrically count the number of printed pages, and the chip's only function was as an alternate method to decrease the cartridge's usable life.

Safety hazards, health risks, and precautions

[edit]Toner clean-up

[edit]Toner particles are formulated to have electrostatic properties and can develop static electric charges when they rub against other particles, objects, or the interiors of transport systems and vacuum hoses. Static discharge from charged toner particles can ignite combustible particles in a vacuum cleaner bag or cause a small dust explosion if sufficient toner is airborne. Toner particles are so fine that they are poorly filtered by conventional household vacuum cleaner filter bags and blow through the motor or back into the room.

If toner spills into the laser printer, a special type of vacuum cleaner with an electrically conductive hose and a high-efficiency (HEPA) filter may be needed for effective cleaning. These specialized tools are called "ESD-safe" (Electrostatic Discharge-safe) or "toner vacuums".

Ozone hazards

[edit]As a normal part of the printing process, the high voltages inside the printer can produce a corona discharge that generates a small amount of ionized oxygen and nitrogen, which react to form ozone and nitrogen oxides. In larger commercial printers and copiers, an activated carbon filter in the air exhaust stream breaks down[citation needed] these noxious gases to prevent pollution of the office environment.

However, some ozone escapes the filtering process in commercial printers, and ozone filters are not used at all in most smaller home printers. When a laser printer or copier is operated for a long period of time in a small, poorly ventilated space, these gases can build up to levels at which the odor of ozone or irritation may be noticed. A potential health hazard is theoretically possible in extreme cases.[36]

Respiratory health risks

[edit]According to a 2012 study conducted in Queensland, Australia, some printers emit sub-micrometer particles which some suspect may be associated with respiratory diseases.[37] Of 63 printers evaluated in the Queensland University of Technology study, 17 of the strongest emitters were made by HP and one by Toshiba. The machine population studied, however, was only those machines already in place in the building and was thus biased toward specific manufacturers. The authors noted that particle emissions varied substantially even among the same model of machine. According to Professor Morawska of the Queensland University of Technology, one printer emitted as many particles as a burning cigarette:[38][39]

The health effects from inhaling ultrafine particles depend on particle composition, but the results can range from respiratory irritation to more severe illness such as cardiovascular problems or cancer.

In December 2011, the Australian government agency Safe Work Australia reviewed existing research and concluded that "no epidemiology studies directly associating laser printer emissions with adverse health outcomes were located" and that several assessments conclude that "risk of direct toxicity and health effects from exposure to laser printer emissions is negligible". The review also observes that, because the emissions have been shown to be volatile or semi-volatile organic compounds, "it would be logical to expect possible health effects to be more related to the chemical nature of the aerosol rather than the physical character of the 'particulate' since such emissions are unlikely to be or remain as 'particulates' after they come into contact with respiratory tissue".[40]

The German Social Accident Insurance has commissioned a human study project to examine the effects on health resulting from exposure to toner dusts and from photocopying and printing cycles. Volunteers (23 control persons, 15 exposed persons and 14 asthmatics) were exposed to laser printer emissions under defined conditions in an exposure chamber. The findings from the study based on a broad spectrum of processes and subjects fail to confirm that exposure to high laser printer emissions initiates a verifiable pathological process resulting in the reported illnesses.[41]

A much-discussed proposal for reducing emissions from laser printers is to retrofit them with filters. These are fixed with adhesive tape to the printer's fan vents to reduce particle emissions. However, all printers have a paper output tray, which is an outlet for particle emissions. Paper output trays cannot be provided with filters, so it is impossible to reduce their contribution to overall emissions with retrofit filters.[42]

Air-transport ban

[edit]After the 2010 cargo plane bomb plot, in which shipments of laser printers with explosive-filled toner cartridges were discovered on separate cargo airplanes, the US Transportation Security Administration prohibited pass-through passengers from carrying toner or ink cartridges weighing over 1 pound (0.45 kg) on inbound flights, in both carry-on and checked luggage.[43][44] PC Magazine noted that the ban would not impact most travelers, as the majority of cartridges do not exceed the prescribed weight.[44]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Laser Printer - Definition of laser printer by Merriam-Webster". merriam-webster.com.

- ^ "Jacob E. Goldman, Founder of Xerox Lab, Dies at 90". The New York Times. December 21, 2011.

In the late 1960s, Xerox, then the dominant manufacturer of office copiers ...

- ^ Gladwell, Malcolm (May 16, 2011). "Creation Myth - Xerox PARC, Apple, and the truth about innovation". The New Yorker. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ Edwin D. Reilly (2003). Milestones in Computer Science and Information Technology. Greenwood Press. ISBN 1-57356-521-0.

starkweather laser-printer.

- ^ a b Roy A. Allan (1 October 2001). A History of the Personal Computer: The People and the Technology. Allan Publishing. pp. 13–23. ISBN 978-0-9689108-3-2.

- ^ a b c William E. Kasdorf (January 2003). The Columbia Guide to Digital Publishing. Columbia University Press. pp. 364, 383. ISBN 978-0-231-12499-7.

- ^ H Ujiie (28 April 2006). Digital Printing of Textiles. Elsevier Science. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-84569-158-5.

- ^ Michael Shawn Malone (2007). Bill & Dave: How Hewlett and Packard Built the World's Greatest Company. Penguin. p. 327. ISBN 978-1-59184-152-4.

- ^ Paul A. Strassmann (2008). The Computers Nobody Wanted: My Years with Xerox. Strassmann, Inc. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-4276-3270-8.

- ^ Hall, Jim (2011). "HP LaserJet-The Early History" (PDF). Hparchive.com. Retrieved June 6, 2011.

- ^ "TPW - CX Printers- Apple". printerworks.com. Archived from the original on 2013-08-01. Retrieved 2014-07-19.

- ^ S. Nagabhushana (2010). Lasers and Optical Instrumentation. I. K. International Pvt Ltd. p. 269. ISBN 978-93-80578-23-1.

- ^ Ganeev, Rashid A. (2014). Laser - Surface Interactions. Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 56. ISBN 978-94-007-7341-7. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Pfiffner, Pamela (2003). Inside the Publishing Revolution: The Adobe Story. Berkeley: Peachpit Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-321-11564-3.

- ^ Brownstein, Mark (November 18, 1991). "SCSI may solve printer data bottlenecks". InfoWorld. 13 (46): 25–28. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ Troast, Randy (March 21, 1994). "Low-cost laser printers". InfoWorld. pp. 68–69, 84–85.

- ^ Grotta, Daniel; Grotta, Sally Wiener (March 28, 1995). "SuperScript 660: NEC's Dumb Printer Is a Smart Buy". PC Magazine. p. 50.

- ^ Mendelson, Edward (September 9, 1997). "A New LaserJet Jewel: HP LaserJet 6L makes 6-ppm printing an affordable venture". PC Magazine. p. 68. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "how Laser Process Technology animation (sic)". Lexmark. 14 July 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-12-21.

- ^ "CompTIA A+ Rapid Review: Printers". MicrosoftPressStore.com.

Laser printers .. complex imaging process ... charge neutralizes ... the drum

- ^ Bhardwaj, Pawan K. (2007). A+, Network+, Security+ Exams in a Nutshell: A Desktop Quick Reference. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-0-596-55151-3.

in most laser printers. ... the surface of the drum.

[page needed] - ^ "HP Virtual Museum: Hewlett-Packard LaserJet printer, 1984". Hp.com. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ^ "Facts about laser printing". Papergear.com. 2010-09-01. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ^ "Print efficiency in the workplace: how to make your office more efficient". ASL. 2017-05-11. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ^ "Pros & Cons for Home Use: Inkjet vs. Laser Printers". Apartment Therapy.

- ^ "Inkjet vs Laser Printers: Pros, Cons & Recommendation for 2019". Office Interiors. August 26, 2019.

- ^ Uwe Steinmueller; Juergen Gulbins (21 December 2010). Fine Art Printing for Photographers: Exhibition Quality Prints with Inkjet Printers. O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4571-0071-0.

- ^ Alexander, Jordan. "Inkjet vs Laser Printer". Alberta Toner. Jordan Ale.

- ^ "Electronic Frontier Foundation - Printer Tracking". Eff.org. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- ^ "Electronic Frontier Foundation Threat to privacy". Eff.org. 2008-02-13. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ^ Anderson, L.V. (June 6, 2017). "Did The Intercept Betray Its NSA Source With Sloppy Reporting?". Digg. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019.

- ^ Wemple, Erik (June 6, 2017). "Did the Intercept bungle the NSA leak?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 13, 2018.

- ^ RTBF documentary "L'obsolescence programmée" by Xavier Vanbuggenhout

- ^ Whiting, Geoff. "What Is a Laser Toner Chip?". Small Business - Chron.com.

- ^ "Hacking the Samsung CLP-315 Laser Printer". Hello World!. 3 March 2012.

- ^ "Photocopiers and Laser Printers Health Hazards" (PDF). www.docs.csg.ed.ac.uk. 2010-04-19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-11. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ^ He C, Morawska L, Taplin L (2012). "Particle emission characteristics of office printers" (PDF). Environ Sci Technol. 41 (17): 6039–45. doi:10.1021/es063049z. PMID 17937279.

- ^ "Particle Emission Characteristics of Office Printers". The Sydney Morning Herald. 2007-08-01.

- ^ "Study reveals the dangers of printer pollution". Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- ^ Drew, Robert (December 2011), Brief Review on Health Effects of Laser Printer Emissions Measured as Particles (PDF), Safe Work Australia, archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-03-04, retrieved 2013-10-23

- ^ Institute for Occupational Safety and Health of the German Social Accident Insurance. "Investigation on health effects of emissions from laserprinters and -copiers, Subproject LMU: Exposition of volunteers in a climatic chamber".

- ^ Institute for Occupational Safety and Health of the German Social Accident Insurance. "Safe laser printers and copiers".

- ^ "UK: Plane Bombs Explosions Were Possible Over U.S". Fox News. Archived from the original on March 29, 2012. Retrieved 2010-11-17.

- ^ a b Hoffman, Tony (2010-11-08). "U.S. Bans Large Printer Ink, Toner Cartridges on Inbound Flights". PC Mag. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

Further reading

[edit]- Pirela, Sandra V.; Lu, Xiaoyan; Miousse, Isabelle; Sisler, Jennifer D.; Qian, Yong; Guo, Nancy; Koturbash, Igor; Castranova, Vincent; Thomas, Treye; Godleski, John; Demokritou, Philip (January 2016). "Effects of intratracheally instilled laser printer-emitted engineered nanoparticles in a mouse model: A case study of toxicological implications from nanomaterials released during consumer use". NanoImpact. 1: 1–8. Bibcode:2016NanoI...1....1P. doi:10.1016/j.impact.2015.12.001. PMC 4791579. PMID 26989787.

External links

[edit]- Gary Starkweather. Birth of the Laser Printer. Computer History Museum – via YouTube.

Laser printing

View on GrokipediaHistory

Invention and early research

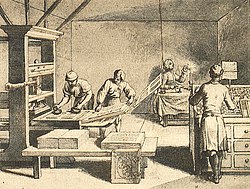

The concept of laser printing emerged from adaptations to xerography, the dry electrophotographic process invented by Chester F. Carlson in 1938, which used light to expose a photoconductive surface. In 1967, Xerox physicist Gary Starkweather, working at the company's Webster Research Center in New York, proposed replacing traditional light sources with a modulated laser beam to create latent images on the photoconductor, enabling high-resolution digital printing directly from computer data.[2] This idea built on the precision of lasers, first demonstrated in 1960, to achieve finer control over image formation than mechanical scanning or LED arrays.[2] Starkweather faced significant internal resistance at Xerox, as managers prioritized protecting sales of existing copiers like the Model 914 over disruptive innovations.[8] Despite this, he constructed the first working prototype in 1969 by integrating a helium-neon laser and acoustic modulator into a modified Xerox 914 copier, producing output at 500 lines per inch resolution.[1] This device demonstrated the viability of laser exposure for xerographic imaging, though it required further refinement for practical use.[2] In 1971, Starkweather transferred to Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center) to advance the technology, developing the Scanning Laser Output Terminal (SLOT).[9] SLOT utilized a Xerox 7000 copier base with a laser beam scanning digital information onto the drum, achieving print speeds of up to 60 pages per minute at 500 dots per inch.[2] Early experiments at PARC validated computer-generated raster images, paving the way for integrating printing with digital computing systems. These prototypes highlighted the potential for non-impact, high-speed printing but revealed challenges in laser stability, optics alignment, and toner compatibility.[3]Commercialization and key milestones

The commercialization of laser printing was pioneered by Xerox Corporation, which introduced the Xerox 9700 Electronic Printing System in 1977 as the first fully commercial laser printer. This system achieved speeds of 120 pages per minute at 300 dots per inch resolution on standard cut-sheet paper, utilizing a xerographic process adapted for high-volume enterprise applications rather than desktop use. Priced for institutional buyers and capable of duplex printing, it demonstrated the viability of non-impact digital printing but remained costly and specialized, with initial sales focused on data centers and print shops.[1][4][2] Widespread adoption accelerated in 1984 with Hewlett-Packard's release of the HP LaserJet, the inaugural desktop laser printer designed for personal computers and small offices. Retailing at about $3,500, it delivered 300 dpi output at 8 pages per minute, leveraging a Canon printing engine with HP's proprietary raster image processor to replace slower daisy-wheel and dot-matrix alternatives. The LaserJet's compatibility with standard software and its reliable, quiet operation drove rapid market penetration, with millions of units sold and the establishment of a dedicated printer cartridge ecosystem.[10][11][12] Subsequent early milestones included the 1985 HP LaserJet Plus, which expanded font and graphics capabilities through enhanced controller software, broadening appeal for document-intensive workflows. By the late 1980s, these developments had shifted printing from centralized services to decentralized office tools, with annual global shipments exceeding 1 million units by 1990, fundamentally altering business communication efficiency.[11][13]Technological evolution post-1980s

The introduction of the Hewlett-Packard LaserJet in 1984 marked a pivotal shift toward affordable desktop laser printing, utilizing a Canon-engineered electrophotographic process with a 300 dpi resolution and 8 pages per minute (ppm) speed, priced at $3,495, which enabled widespread adoption in personal computing environments.[11][12] This model integrated laser scanning with xerographic toner transfer, reducing size and cost compared to prior Xerox systems, which were larger and enterprise-oriented.[13] Subsequent refinements in the late 1980s and 1990s focused on resolution and speed, with laser diode enhancements allowing outputs to reach 600 dpi by the early 1990s and speeds exceeding 20 ppm in models like later HP LaserJet series, driven by improved raster image processors (RIPs) and photoconductor durability.[14] Color laser printing emerged commercially in the mid-1990s, exemplified by Apple's Color LaserWriter 12/600PS in 1995, which employed four toner cartridges (cyan, magenta, yellow, black) in tandem engines for 600 dpi full-color output, though initial units were costly and slower at 12 ppm.[15] These innovations stemmed from advances in precise toner layering and laser modulation to separate color channels without compromising monochrome efficiency.[16] Into the 2000s, toner formulations evolved from powdered particles to chemically prepared toners with smaller, uniform sizes (around 5-7 micrometers), improving image sharpness and reducing fusing temperatures to minimize paper curl and energy use, while drum materials shifted toward amorphous silicon for extended lifespans beyond 100,000 pages.[17] Print speeds scaled to 40-70 ppm in production models by the mid-2000s, supported by faster polygon mirrors and LED array hybrids in some designs, alongside duplexing mechanisms for automatic double-sided printing via paper path inverters. Networking integration via Ethernet and wireless protocols became standard, facilitating distributed office workflows, with multifunction devices combining printing, scanning, and copying in compact units.[13] These developments lowered operational costs per page to under 2 cents for monochrome, prioritizing reliability over inkjet alternatives for high-volume text output.Printing process

Raster image processing

In laser printing, raster image processing refers to the conversion of input data—typically in page description languages such as HP's Printer Control Language (PCL) or Adobe PostScript—into a high-resolution bitmap that represents the final printed image as an array of pixels. This step occurs in the printer's controller or embedded raster image processor (RIP), which interprets vector-based commands for text, graphics, and images, rendering them into a grid of dots corresponding to the printer's resolution, often 600 dots per inch (dpi) or higher.[18][19] The process ensures precise control over the electrophotographic imaging drum, where each pixel determines whether the laser beam discharges a spot on the photoconductor.[20] The RIP begins by parsing the input stream: for PostScript, it executes a stack-based virtual machine to handle operators for drawing lines, curves, fills, and raster operations; for PCL, it processes simpler cursor-movement and graphics commands optimized for printer efficiency. Fonts are rasterized using hinting algorithms to maintain legibility at low resolutions, compensating for pixel grid alignment—early systems like those in the 1984 Apple LaserWriter relied on Adobe's interpreter for this, enabling scalable typography.[19] Graphics and continuous-tone images undergo halftoning, where multi-level data is dithered into binary on/off patterns via techniques like ordered dithering or error diffusion to simulate grayscales, with cell sizes typically 4x4 to 16x16 pixels for 300 dpi printers.[18] This bitmap is then buffered in the printer's RAM as a full-page monochrome or color-separated array—for an 8.5-by-11-inch page at 600 dpi, a black-and-white buffer requires approximately 23 megabits, necessitating sufficient memory to avoid banding or compression artifacts.[20] In color laser printers, the RIP performs additional color management, decomposing RGB or CMYK inputs into plane-separated rasters for sequential drum exposure, often using ICC profiles for device calibration to minimize gamut mismatches. Processing time varies by complexity; simple text pages rasterize in milliseconds, while image-heavy jobs can take seconds, with hardware-accelerated RIPs in modern printers (post-2000s) leveraging ASICs for speeds up to 120 pages per minute at 1200 dpi effective resolution via interpolation.[19] Once complete, the bitmap modulates the laser diode's pulses via a polygon mirror scanner, directly linking digital preparation to physical latent image formation without intermediate film.[18] This embedded RIP architecture, pioneered in Xerox and HP systems from the 1970s, distinguishes laser printers from plotters by enabling bandless, high-fidelity output independent of host computation.[20]Charging the photoconductor

The charging of the photoconductor initiates the electrophotographic process in laser printing by establishing a uniform electrostatic charge across the surface of the rotating cylindrical drum, typically composed of an organic photoconductor (OPC) material layered on an aluminum base.[21] This step ensures that the drum's surface potential is consistent, usually negative at around -600 to -700 volts, preparing it for selective discharge by the laser exposure.[22] Traditionally, charging employs a corona discharge mechanism using a corotron wire—a thin, high-tension wire positioned parallel to the drum and biased with a high negative DC voltage, often -6,000 volts.[22] The applied voltage ionizes ambient air molecules adjacent to the wire, generating a corona plasma of negative ions that migrate toward the earthed drum surface under the electric field, depositing charge and achieving uniform sensitization without direct contact.[23] A control grid may modulate ion flow to precisely regulate surface potential and minimize overcharging.[24] In some designs, particularly to reduce ozone emissions from corona discharge—which occurs as oxygen molecules ionize into O3—a contact charging roller replaces the wire; this rubber or conductive roller, biased to the desired potential, physically contacts the drum to transfer charge via triboelectric or capacitive means.[25] Both methods rely on the photoconductor's ability to retain charge in unexposed areas due to its high dark resistivity, while exposed regions will conduct away charge during imaging.[23] Historical drums used selenium-based photoconductors, which required similar charging but have largely been supplanted by more durable OPC variants.[26]Exposing with laser

In the exposing step of the laser printing process, a modulated laser beam selectively illuminates the uniformly charged photoconductive drum to discharge specific areas, forming a latent electrostatic image that represents the desired print output.[27] The photoconductive material on the drum, typically an organic photoconductor or selenium-based layer, acts as an insulator in darkness but becomes conductive upon exposure to light of appropriate wavelength, allowing accumulated charge to dissipate to ground in illuminated regions.[28] This discharge lowers the surface potential from approximately -600 to -100 volts in exposed areas, while unexposed regions retain the full negative charge, creating electrostatic contrast for subsequent toner adhesion.[29] The laser source is usually a semiconductor diode laser emitting coherent light at around 780 nanometers in the near-infrared spectrum, chosen to match the photoconductor's sensitivity for efficient charge generation via photoconductivity.[30] The beam is directed onto the drum via a scanning mechanism, commonly a rotating polygonal mirror that deflects the fixed laser across the drum's width at high speed, synchronized with the drum's rotation to rasterize the image line by line.[31] Modulation of the laser—turning it on and off rapidly—is controlled by digital video signals derived from the raster image processor (RIP), enabling resolutions typically from 300 to 1200 dots per inch depending on spot size and scan precision.[31] This optical exposure step, pioneered in Gary Starkweather's work at Xerox in the late 1960s, replaced earlier LED or xenon lamp arrays with a single laser for faster, more precise imaging, forming the core innovation of laser printing.[24] Precise alignment of the laser optics and f-theta lenses ensures a flat focal plane across the scan field, minimizing distortion and maintaining uniform exposure density essential for high-quality reproduction.[23] Variations in laser power or wavelength can affect sensitivity, with modern systems optimizing for organic photoconductors that offer broader spectral response and longer drum life compared to amorphous selenium drums used in early models.[24]Developing the image

In the developing stage, the invisible electrostatic latent image on the photoconductor drum—consisting of discharged areas (near 0 V) where the laser beam struck and residual charged areas (typically -500 to -600 V)—is converted into a visible toner image through electrostatic attraction.[32] Toner, a fine powder comprising plastic resin particles (5–10 micrometers in diameter) pigmented with carbon black or colorants and fused with polymers for heat-melt properties, is stored in a cartridge and charged triboelectrically (via friction against carrier beads or the developer roller) to a negative potential of approximately -10 to -50 V.[29] The developer unit, often employing a magnetic brush roller system in modern laser printers, meters and presents a thin layer of toner to the drum surface. A bias voltage (around -200 to -400 V) applied to the developer roller creates an electric field that repels toner from the highly negative background areas while attracting it preferentially to the less negative (discharged) image areas, where the potential gradient is strongest; this "jumping development" ensures toner adheres only to the latent image without bridging to non-image regions.[33] The process relies on the photoconductor's high resistivity in unexposed areas to maintain charge separation, preventing toner migration to background, with development occurring in milliseconds as the drum rotates at speeds up to 100–200 mm/s in typical office printers.[27] Variations include single-component (non-magnetic toner rolled directly) versus dual-component (toner mixed with magnetic carrier beads for consistent charging) systems, with the latter common in higher-volume printers for uniform tribocharging and reduced agglomeration; however, single-component dominates consumer devices for simplicity and cost.[23] Incomplete development can result from low toner charge (e.g., due to humidity affecting triboelectricity) or mismatched bias voltage, leading to faint prints or ghosting, while excess toner application risks smudging during transfer.[34] In color laser printing, this stage repeats for each primary toner (cyan, magenta, yellow, black) at separate developer stations, with precise registration to align layers.[35]Transferring to paper

The toner image developed on the photoconductor drum, consisting of negatively charged particles adhering to the latent electrostatic image, is transferred to paper through electrostatic attraction.[25] As the drum rotates, a sheet of paper is synchronously fed from the paper tray into contact with the drum surface at the transfer station, ensuring matched speeds to avoid image distortion or smearing.[36][37] To facilitate transfer, the underside of the paper is positively charged by a transfer corona assembly, which applies a high-voltage discharge—typically around +5 to +6 kV—from a corona wire or roller to ionize surrounding air and deposit positive ions onto the paper.[25] This induced positive charge on the paper exceeds the negative potential holding the toner to the drum (usually -400 to -600 V in exposed areas), causing the toner particles to migrate electrostatically from the drum to the paper fibers.[29] The process relies on Coulomb's law, where the attractive force between oppositely charged bodies drives the transfer efficiency, though some residual toner—often 5-10%—remains on the drum due to incomplete detachment influenced by factors like humidity and paper surface properties.[25] In monochrome laser printers, direct drum-to-paper transfer predominates, but color models frequently employ an intermediate transfer belt or drum to aggregate multiple toner layers before a single transfer to paper, reducing misalignment risks and enabling higher registration accuracy.[29] Bias transfer rollers, charged positively, can supplement or replace corona units in modern designs to improve transfer uniformity and reduce ozone emissions from corona discharge.[37] Post-transfer, the paper proceeds to the fuser while the drum continues to the cleaning stage.[36]Fusing the toner

After the toner image is electrostatically transferred to the paper, the sheet enters the fuser assembly to permanently bond the toner particles to the substrate.[31] The fuser typically consists of a heated fuser roller and a pressure roller that apply both thermal energy and mechanical force as the paper passes between them.[38] Heat from the fuser roller, often generated by an internal halogen lamp or ceramic heater, raises the temperature to soften the thermoplastic resin in the toner particles, while the pressure roller embeds the molten toner into the paper fibers.[39] Toner, primarily composed of polymer resins such as polyester or styrene-acrylate, has a glass transition temperature that allows it to melt and flow under controlled heat without fully liquefying, ensuring sharp image edges are preserved.[31] Fusing temperatures generally range from 150°C to 200°C, calibrated to achieve rapid bonding within milliseconds of contact to match printer throughput speeds.[38] A release agent, such as silicone oil, is applied to the fuser surface to prevent the molten toner from adhering to the rollers, minimizing offset and ensuring clean output.[39] The process relies on the viscoelastic properties of the toner, where insufficient heat results in poor adhesion and flaking, while excessive heat can cause excessive flow, leading to blurred edges or toner smearing.[31] In modern designs, feedback sensors monitor and regulate fuser temperature to optimize energy use and prevent paper jams from uneven heating.[38] Post-fusing, the paper exits the assembly, completing the core printing cycle before any optional duplexing or finishing steps.[39]Cleaning and recharging

After toner transfer to the paper, residual toner particles adhering to the photoconductor drum surface are removed to prevent interference with subsequent image formation. This cleaning step primarily employs a flexible rubber or polyurethane blade pressed against the rotating drum, which scrapes off the loose toner particles through mechanical contact.[27] In many designs, a secondary fur brush or magnetic brush follows the blade to capture any remaining fine particles, directing them into a waste reservoir or, less commonly, recycling them back to the developer unit for reuse.[27][40] Residual electrostatic charge on the drum, which could retain parts of the previous latent image, is then dissipated to return the photoconductor to a neutral, reusable state. Uniform exposure from an erase lamp, typically a halogen or LED array emitting broad-spectrum light, photoconducts the entire drum surface, allowing charges to flow to ground and neutralize voltage disparities.[41][42] Alternatively, some systems use a discharge corona with alternating current to ionize air and balance charges without light.[41] Once cleaned and discharged, the photoconductor drum is recharged to a uniform negative potential, restoring its sensitivity for the next cycle's latent image creation. This is achieved via a primary charging unit, such as a corotron wire applying high-voltage corona discharge (around 5-7 kV) to generate ions that deposit on the drum surface, or a contact roller biased to -1 kV for more efficient, ozone-reduced charging in modern units.[43][23] The resulting surface voltage, typically -500 to -700 V, ensures consistent electrophotographic behavior across the drum.[23] These steps collectively enable the drum's reuse for thousands of cycles, with lifespan limited by mechanical wear on the cleaning blade and photoconductor degradation rather than toner exhaustion.[40]Process variations and common malfunctions

Laser printers employ variations in the electrophotographic process to optimize performance, reduce emissions, or adapt to specific applications. One key variation involves the photoconductor medium, which can be either a rotating drum or a flexible belt; drums are common in compact desktop models for their durability, while belts enable higher-speed production in industrial printers by allowing continuous looping.[31][44] Charging methods also differ: traditional corona wire systems generate an electrostatic charge via high-voltage discharge, producing ozone as a byproduct, whereas modern charge rollers apply contact charging with less ozone emission and lower power use, becoming standard in printers post-1990s to meet environmental regulations.[22][23] Transfer mechanisms vary between direct electrostatic transfer to paper and intermediate transfer using a belt, the latter improving registration accuracy in high-volume or color systems by allowing multiple toner layers before paper contact.[45] Common malfunctions in laser printing often stem from component wear, improper maintenance, or material incompatibilities, manifesting as print defects traceable to specific process steps.| Defect | Description and Cause | Affected Process Step |

|---|---|---|

| Faded or light prints | Insufficient toner adhesion due to low toner levels, incorrect paper weight, or depleted drum charge; occurs when electrostatic forces fail to attract enough toner particles.[46] | Charging or developing |

| Streaks or lines | Vertical marks from damaged cleaning blades, contaminated rollers, or scratched photoconductor surfaces, disrupting uniform charge or toner application.[47] | Cleaning or exposing |

| Ghosting | Faint repeated images from residual toner on the photoconductor or improper discharge, caused by worn drums or inadequate quenching.[48] | Cleaning or recharging |

| Smudging or poor fusing | Toner rubs off easily due to fuser underheating, wrong paper type, or faulty thermistor, failing to melt toner onto fibers.[49] | Fusing |

| Paper jams | Blockages from curled paper, debris, or misaligned paths, often linked to humidity affecting paper curl or worn feed rollers.[50] | Transferring or fusing |

Technical performance

Print speed and resolution

Laser printers achieve print speeds typically ranging from 12 to 20 pages per minute (PPM) for entry-level desktop models, with commercial units capable of 20 to 100 PPM in monochrome mode and up to 75 PPM in color.[51][52] PPM measures the number of standard text pages produced in one minute under controlled conditions, such as simplex printing on plain paper.[53] Actual speeds depend on factors including document complexity, print mode (draft versus high quality), paper handling (duplex reduces effective PPM), and hardware limitations like processor speed and memory.[54][55] Resolution in laser printing is quantified in dots per inch (DPI), representing the density of toner dots placed on the page to form images and text. Standard resolutions for most laser printers fall between 300 and 600 DPI, sufficient for sharp text and basic graphics in office documents.[56] Higher-end models support 1200 DPI or greater, enhancing detail for photographs or fine-line graphics, though this increases processing demands.[56] Effective resolution often exceeds native DPI through interpolation techniques, but print quality also hinges on toner particle size and photoconductor precision rather than DPI alone.[57] Print speed and resolution trade off inversely: selecting higher DPI settings demands more raster image processing (RIP) time, slowing output by up to 50% or more compared to lower resolutions on the same hardware.[56] For instance, a printer rated at 40 PPM in draft mode at 300 DPI may drop to 20 PPM at 1200 DPI due to the quadrupled data volume per inch.[58] Manufacturers standardize speed claims at minimum resolutions (e.g., 300 DPI) for text-heavy pages to reflect real-world office use, while resolution scalability allows user adjustment via drivers for balancing quality and throughput.[59]Media compatibility and handling

Laser printers are optimized for plain paper with weights typically ranging from 60 to 120 gsm (16 to 32 lb bond), though specific models support up to 163 gsm in standard trays and heavier cardstock via manual feeds.[60][61] Paper must be laser-compatible to withstand the fuser's heat (up to 200°C), avoiding inkjet formulations that may cause jamming or poor adhesion.[62] Recycled paper is viable if within weight limits, but humidity-sensitive stocks exceeding 120 gsm risk curling post-fusing. Specialty media includes envelopes (plain, non-wrinkled, without plastic windows unless laser-rated), labels on carrier sheets, and overhead transparencies designed for thermal fusing to prevent melting or ghosting.[63][64] Cardstock up to 220 gsm and glossy stocks are supported in select models like the Dell S5840cdn, but require straight-path feeding to minimize jams from stiffness.[65] Sizes conform to standards such as Letter (8.5 x 11 inches) or A4 (210 x 297 mm), with multipurpose trays accommodating custom dimensions up to legal or tabloid.[65] Handling involves cassette input trays (250-500 sheets capacity for plain paper), friction-feed rollers for pickup and registration, and output stacks or bins.[66] Automatic duplexing reverses paper via internal paths for double-sided printing, but thick media (>120 gsm) often triggers jams at de-skew rollers due to insufficient torque.[67] Manual slots enable single-sheet feeding for envelopes or labels, bypassing main paths to reduce multi-feed risks.[68] Jams arise from overfilled trays, worn pickup rollers, or electrostatic buildup on non-laser media, with clearance requiring power-off access to fuser and duplex areas.[69][70] Mitigation includes fanning stacks, maintaining 40-60% humidity, and adhering to per-model limits—e.g., avoiding glossy films in high-heat cycles to prevent offset.[71][70]Energy consumption and efficiency

Laser printers primarily consume energy during the fusing process, where a heated fuser roller or belt, operating at temperatures of 150–200°C, bonds toner particles to the paper substrate; this stage accounts for 70–90% of total printing energy use, with peak power draws ranging from 500 to 1500 watts for typical office models depending on print speed and paper size.[72] The laser scanning and photoconductor charging components contribute minimally, under 50 watts combined, while paper transport motors add another 50–100 watts.[73] In non-printing modes, ENERGY STAR-certified laser printers achieve low standby power of 3–10 watts and sleep/off-mode consumption below 1 watt, enabling automatic power-down after inactivity to minimize idle energy waste; for instance, the HP Color LaserJet Pro MFP M479fdw records 0.08 watts in off mode.[74] Typical electricity consumption (TEC), measured under standardized weekly cycles of printing, idle, and sleep simulating moderate office use, falls between 0.2 and 0.7 kWh per week for mid-range monochrome and color models, respectively.[74][75] Energy efficiency per printed page for laser printers averages 0.005–0.01 kWh for monochrome output at 20–40 pages per minute, influenced by toner coverage (higher coverage increases fusing energy by 10–20%) and fuser warm-up time, which can add 0.02–0.05 kWh for initial prints after idle periods in low-volume scenarios.[73] High-volume operation improves relative efficiency, as the fuser maintains heat across multiple sheets, reducing per-page energy to under 0.004 kWh compared to slower inkjet printers that may require prolonged operation for equivalent output.[76] Modern designs incorporate ceramic heaters, improved insulation, and on-demand fuser activation to cut warm-up energy by up to 50% versus older halogen-lamp models, aligning with ENERGY STAR Version 3.0 requirements for at least 30% efficiency gains over baseline products.[77][78]Color laser printing

Color process mechanics

Color laser printers achieve full-color output through the subtractive CMYK model, employing separate toners for cyan, magenta, yellow, and black to mix colors on the print medium.[31] Each color separation is generated digitally by decomposing the input image into four binary bitmaps, one per toner color, based on halftoning algorithms that simulate continuous tones via varying dot densities.[79] In prevalent tandem configurations, four distinct imaging stations process the colors sequentially in a single paper pass, enabling higher speeds compared to sequential single-drum systems.[79] Each station mirrors the core electrophotographic steps: a photoconductive drum is uniformly charged to a negative potential, typically around -600 volts, using a corona wire or charge roller.[80] A laser beam, modulated by the color-specific bitmap, scans the drum surface, discharging image areas to near-ground potential while leaving non-image areas charged, forming a latent electrostatic image.[31] Development occurs as negatively charged toner particles, carried in a developer unit with magnetic rollers, are attracted selectively to the discharged regions on the drum due to the potential difference.[27] Color toners consist of pigmented resin particles, approximately 5-10 micrometers in diameter, triboelectrically charged via friction in the developer housing to ensure opposite polarity to the latent image.[81] This per-station independence allows simultaneous preparation of color layers, though mechanical synchronization is required to prevent misalignment, with each drum rotating at speeds synchronized to the paper feed rate, often exceeding 50 mm/second in high-volume models.[82] Alternative architectures, such as single-drum sequential processing, reuse one drum for all colors by cleaning and recharging between separations, but this reduces throughput as the paper or intermediate carrier awaits each layer.[83] Tandem systems predominate in commercial printers for their efficiency, with imaging units often integrated into replaceable cartridges containing the drum, developer, and toner reservoir for each color.[84] Empirical tests confirm that proper charging uniformity, typically within 10-20 volts across the drum, is critical to avoid color shifts from uneven toner adhesion.[80]Transfer and registration techniques

In color laser printers, toner transfer typically occurs via electrostatic attraction, where negatively charged toner particles are drawn from the organic photoconductor (OPC) drum to either paper directly or an intermediate transfer belt (ITB) by applying a bias voltage (typically 500–900 V) to a transfer roller or corona device, achieving efficiencies of 90% to 97%.[85] Direct transfer methods contact the paper with the drum or roller, but in color systems, this is less common due to alignment challenges; instead, tandem configurations with four OPC drums (one per CMYK color) sequentially layer toner onto a flexible ITB, which features an insulating outer layer for toner adhesion and a conductive inner layer for charge application.[85] The composite image on the ITB is then transferred to paper in a single secondary step using a secondary transfer roller, minimizing paper handling and enabling higher speeds in single-pass engines compared to multi-pass designs.[85] Color registration ensures precise overlay of cyan, magenta, yellow, and black toner layers to prevent misalignment artifacts like fringing or moiré patterns, with tolerances often below 0.001 inches (25 micrometers).[85] Mechanical synchronization of drum rotations and belt advancement via stepper motors provides baseline alignment, while active feedback systems use inline optical sensors (e.g., LED-based) to detect fiducial marks or printed test patches on the ITB, dynamically adjusting laser timing, bias voltages, or motor speeds for correction.[85] Capacitive or spectrophotometric sensors may also measure density variations in calibration patterns to fine-tune registration, as implemented in devices like Dell Color Laser Printer 1320c, where users or firmware print and analyze adjustment charts for manual or automatic offsets.[86] Single-pass tandem systems enhance registration stability over four-pass sequential methods by reducing cumulative errors from multiple paper feeds, though both rely on uniform toner charge to avoid transfer defects like hollow images.[85]Performance differences from monochrome

Color laser printers generally operate at slower print speeds than monochrome laser printers, as the former require multiple passes or sequential toner applications for cyan, magenta, yellow, and black, increasing processing time. Monochrome printers, using a single black toner, achieve speeds up to 50 pages per minute (ppm), while color models typically max out at 25 ppm for full-color output.[87] Even for monochrome printing on color devices, speeds may lag behind dedicated monochrome units due to engine design prioritizing color handling.[54] In terms of resolution, monochrome laser printers often deliver sharper text output with effective resolutions exceeding standard color models, as the absence of color layering avoids alignment errors that can blur fine details in color printing. Color lasers, while capable of 600–2400 dpi, suffer from registration inaccuracies between color planes, leading to potential moiré patterns or reduced clarity in high-contrast edges compared to the uniform deposition in monochrome.[88] This results in monochrome printers excelling in text-heavy documents, where precision is paramount, whereas color printers trade some acuity for gamut expansion in graphical content. However, for documents with colored text, color laser printers provide true color output without converting colors to grayscale, ensuring clear reproduction of specific hues like red or blue.[89] This capability, alongside their fast speeds and durable fused-toner prints resistant to smudging, makes them preferable for such applications.[90] Operational reliability can differ, with color printers exhibiting higher susceptibility to toner fusion issues or drum wear from multi-color mechanics, potentially increasing downtime versus the simpler monochrome architecture. Empirical reviews indicate color models like the Brother HL-L3295CDW achieve moderate speeds but incur elevated per-page times for complex jobs due to these factors.[90] Overall, these differences stem from the causal complexity of subtractive color synthesis, prioritizing versatility over the streamlined efficiency of single-toner monochrome printing.Business and economic aspects

Market comparison with inkjet printers

In the global printers market, valued at approximately USD 52 billion in 2023, inkjet printers held a leading position with around 40% market share in 2024, driven primarily by their dominance in consumer and home office segments where color versatility and lower upfront costs appeal to occasional users.[91] Laser printers, by contrast, accounted for a smaller hardware revenue share, with the market sized at USD 9.62 billion in 2023, reflecting their concentration in business and enterprise environments favoring high-volume monochrome output.[92] This segmentation arises from empirical differences in total cost of ownership: laser printers achieve a cost per page of 2-5 cents for monochrome printing, compared to 5-10 cents for inkjet black-and-white and 15-25 cents for color, making lasers more economical for volumes exceeding 500 pages monthly.[93][94] Nonetheless, monochrome laser printers suit home or small office use, particularly as reliable and affordable multifunction printers (MFPs) handling printing, scanning, and copying with sharp text quality, low running costs, and toner powder that avoids drying or clogging issues unlike liquid ink, which remains viable for years even with infrequent use.[6][95] They offer rapid printing speeds, crisp text resolution, and precision for black-only outputs such as patterns and floor plans when color is unnecessary. For home use involving mixed color printing and graphics, color laser printers have higher running costs (approximately 2–3¢ per black page and 12–13¢ per color page), while ink tank printers (a type of inkjet with refillable tanks) offer much lower costs (under 1¢ per page), making them more economical for low-volume applications.[96][97] However, for low-volume color printing on single-sided A4 paper, particularly with infrequent use, laser printers are overall more suitable due to toner that does not dry or clog, low maintenance even when idle, fast printing speeds, and sharp text. Laser disadvantages include higher initial costs and less vibrant colors suitable for documents rather than professional photos. Inkjet advantages encompass better color reproduction, especially in modern ink tank models with lower per-page costs, but disadvantages involve traditional cartridge models prone to drying and clogging, with ink tank models improved yet potentially requiring occasional cleaning for infrequent use.[98][6] Business adoption tilts heavily toward laser technology, where monochrome models comprise over 30% of multifunctional printer sales in office settings, supported by faster speeds (up to 50 pages per minute versus inkjet's 20-30) and reliability for text-heavy documents.[99] Inkjet's edge in the consumer market stems from superior photo-quality output and multifunctionality for low-volume color needs, though declining unit shipments in regions like Europe—coupled with eroding laser share there—highlight saturation and shifting preferences toward digital alternatives.[100] Laser markets exhibit stronger projected growth, with a 5.1% CAGR through 2030, fueled by efficiency gains in laser technology outpacing inkjet's 3-4% trajectory in hardware sales.[92][101] Overall hardcopy peripherals revenue, including consumables, reached USD 138.6 billion in 2024, where inkjet captured 45% but laser advanced at a 6.1% growth rate, underscoring lasers' consumables efficiency (toner yields 5,000-10,000 pages per cartridge versus inkjet's 200-500).[102][101] This dynamic positions laser printers as the preferred choice for cost-sensitive commercial applications, while inkjet sustains volume through affordable entry-level models, though long-term market erosion for both technologies continues amid paperless trends.[103]Toner cartridge economics and smart chip technology

Laser printer manufacturers often employ a razor-and-blades business model, selling printers at low margins or at a loss while deriving primary revenue from high-margin toner cartridges.[104] This approach results in toner cartridges costing $50 to $150 each, significantly exceeding the initial printer purchase price for many models, though high page yields—often 1,000 to 10,000 pages per cartridge—yield a lower cost per page of approximately 1 to 5 cents for monochrome printing.[105] [106] Smart chips embedded in toner cartridges facilitate communication between the cartridge and printer firmware, tracking usage via metrics such as drum rotations or page counts to estimate remaining toner levels and alert users to low supply.[107] These chips, which store cartridge-specific data like model compatibility and yield specifications, also enable printers to detect installation of non-original or refilled units, potentially enforcing digital rights management (DRM) protocols that restrict functionality or reduce print quality.[108] Manufacturers justify this technology for maintaining print quality and preventing warranty-voiding damage from incompatible consumables, though it has drawn criticism for inflating costs by limiting access to cheaper third-party alternatives.[109] Firmware updates from companies like Brother and HP have increasingly integrated smart chip verification to phase out third-party toner support, prompting accusations of vendor lock-in that prioritizes recurring revenue over consumer choice.[109] In response to such practices, HP announced in July 2024 the discontinuation of its HP+ DRM program for LaserJet printers, allowing greater flexibility with non-subscription toner while retaining it for inkjets.[110] Empirical data from aftermarket suppliers indicates compatible cartridges with cloned or bypassed chips can achieve comparable yields at 20-50% lower cost, though reliability varies and may void manufacturer warranties.[111]Industry controversies over DRM and subscriptions