Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Histone deacetylase

View on Wikipedia| Histone deacetylase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

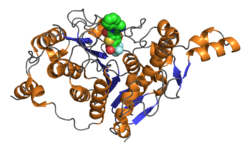

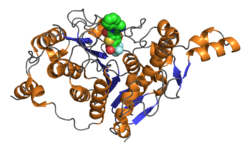

Catalytic domain of human histone deacetylase 4 with bound inhibitor. PDB rendering based on 2vqj.[1] | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 3.5.1.98 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9076-57-7 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Histone deacetylase superfamily | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Hist_deacetyl | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00850 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR000286 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1c3s / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Histone deacetylases (EC 3.5.1.98, HDAC) are a class of enzymes that remove acetyl groups (O=C-CH3) from an ε-N-acetyl lysine amino acid on both histone and non-histone proteins.[2] HDACs allow histones to wrap the DNA more tightly.[3] This is important because DNA is wrapped around histones, and DNA expression is regulated by acetylation and de-acetylation. HDAC's action is opposite to that of histone acetyltransferase. HDAC proteins are now also called lysine deacetylases (KDAC), to describe their function rather than their target, which also includes non-histone proteins.[4] In general, they suppress gene expression.[5]

HDAC super family

[edit]Together with the acetylpolyamine amidohydrolases and the acetoin utilization proteins, the histone deacetylases form an ancient protein superfamily known as the histone deacetylase superfamily.[6]

Classes of HDACs in higher eukaryotes

[edit]HDACs, are classified in four classes depending on sequence homology to the yeast original enzymes and domain organization:[7]

| Class | Members | Catalytic sites | Subcellular localization | Tissue distribution | Substrates | Binding partners | Knockout phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | HDAC1 | 1 | Nucleus | Ubiquitous | Androgen receptor, SHP, p53, MyoD, E2F1, STAT3 | – | Embryonic lethal, increased histone acetylation, increase in p21 and p27 |

| HDAC2 | 1 | Nucleus | Ubiquitous | Glucocorticoid receptor, YY1, BCL6, STAT3 | – | Cardiac defect | |

| HDAC3 | 1 | Nucleus | Ubiquitous | SHP, YY1, GATA1, RELA, STAT3, MEF2D | NCOR1[8] | – | |

| HDAC8 | 1 | Nucleus/cytoplasm | Ubiquitous? | – | EST1B | – | |

| IIA | HDAC4 | 1 | Nucleus / cytoplasm | heart, skeletal muscle, brain | GCMA, GATA1, HP1 | RFXANK | Defects in chondrocyte differentiation |

| HDAC5 | 1 | Nucleus / cytoplasm | heart, skeletal muscle, brain | GCMA, SMAD7, HP1 | REA, estrogen receptor | Cardiac defect | |

| HDAC7 | 1 | Nucleus / cytoplasm / mitochondria | heart, skeletal muscle, pancreas, placenta | PLAG1, PLAG2 | HIF1A, BCL6, endothelin receptor, ACTN1, ACTN4, androgen receptor, Tip60 | Maintenance of vascular integrity, increase in MMP10 | |

| HDAC9 | 1 | Nucleus / cytoplasm | brain, skeletal muscle | – | FOXP3 | Cardiac defect | |

| IIB | HDAC6 | 2 | Mostly cytoplasm | heart, liver, kidney, placenta | α-Tubulin, HSP90, SHP, SMAD7 | RUNX2 | – |

| HDAC10 | 1 | Mostly cytoplasm | liver, spleen, kidney | – | – | – | |

| III | sirtuins in mammals (SIRT1, SIRT2, SIRT3, SIRT4, SIRT5, SIRT6, SIRT7) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sir2 in the yeast S. cerevisiae | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| IV | HDAC11 | 2 | Nucleus / cytoplasm | brain, heart, skeletal muscle, kidney | – | – | – |

HDAC (except class III) contain zinc and are known as Zn2+-dependent histone deacetylases.[9] They feature a classical arginase fold and are structurally and mechanistically distinct from sirtuins (class III), which fold into a Rossmann architecture and are NAD+ dependent.[10]

Subtypes

[edit]HDAC proteins are grouped into four classes (see above) based on function and DNA sequence similarity. Class I, II and IV are considered "classical" HDACs whose activities are inhibited by trichostatin A (TSA) and have a zinc dependent active site, whereas Class III enzymes are a family of NAD+-dependent proteins known as sirtuins and are not affected by TSA.[11] Homologues to these three groups are found in yeast having the names: reduced potassium dependency 3 (Rpd3), which corresponds to Class I; histone deacetylase 1 (hda1), corresponding to Class II; and silent information regulator 2 (Sir2), corresponding to Class III. Class IV contains just one isoform (HDAC11), which is not highly homologous with either Rpd3 or hda1 yeast enzymes,[12] and therefore HDAC11 is assigned to its own class. The Class III enzymes are considered a separate type of enzyme and have a different mechanism of action; these enzymes are NAD+-dependent, whereas HDACs in other classes require Zn2+ as a cofactor.[13]

Evolution

[edit]HDACs are conserved across evolution, showing orthologs in all eukaryotes and even in Archaea. All upper eukaryotes, including vertebrates, plants and arthropods, possess at least one HDAC per class, while most vertebrates carry the 11 canonical HDACs, with the exception of bone fish, which lack HDAC2 but appears to have an extra copy of HDAC11, dubbed HDAC12. Plants carry additional HDACs compared to animals, putatively to carry out the more complex transcriptional regulation required by these sessile organisms. HDACs appear to be deriving from an ancestral acetyl-binding domain, as HDAC homologs have been found in bacteria in the form of Acetoin utilization proteins (AcuC) proteins.[3]

Subcellular distribution

[edit]Within the Class I HDACs, HDAC1, 2, and 3 are found primarily in the nucleus, whereas HDAC8 is found in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm, and is also membrane-associated. Class II HDACs (HDAC4, 5, 6, 7 9, and 10) are able to shuttle in and out of the nucleus, depending on different signals.[14][15]

HDAC6 is a cytoplasmic, microtubule-associated enzyme. HDAC6 deacetylates tubulin, Hsp90, and cortactin, and forms complexes with other partner proteins, and is, therefore, involved in a variety of biological processes.[16]

Function

[edit]Histone modification

[edit]Histone tails are normally positively charged due to amine groups present on their lysine and arginine amino acids. These positive charges help the histone tails to interact with and bind to the negatively charged phosphate groups on the DNA backbone. Acetylation, which occurs normally in a cell, neutralizes the positive charges on the histone by changing amines into amides and decreases the ability of the histones to bind to DNA. This decreased binding allows chromatin expansion, permitting genetic transcription to take place. Histone deacetylases remove those acetyl groups, increasing the positive charge of histone tails and encouraging high-affinity binding between the histones and DNA backbone. The increased DNA binding condenses DNA structure, preventing transcription.

Histone deacetylase is involved in a series of pathways within the living system. According to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), these are:

- Environmental information processing; signal transduction; notch signaling pathway PATH:ko04330

- Cellular processes; cell growth and death; cell cycle PATH:ko04110

- Human diseases; cancers; chronic myeloid leukemia PATH:ko05220

Histone acetylation plays an important role in the regulation of gene expression. Hyperacetylated chromatin is transcriptionally active, and hypoacetylated chromatin is silent. A study on mice found that a specific subset of mouse genes (7%) was deregulated in the absence of HDAC1.[17] Their study also found a regulatory crosstalk between HDAC1 and HDAC2 and suggest a novel function for HDAC1 as a transcriptional coactivator. HDAC1 expression was found to be increased in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia subjects,[18] negatively correlating with the expression of GAD67 mRNA.

Non-histone effects

[edit]It is a mistake to regard HDACs solely in the context of regulating gene transcription by modifying histones and chromatin structure, although that appears to be the predominant function. The function, activity, and stability of proteins can be controlled by post-translational modifications. Protein phosphorylation is perhaps the most widely studied and understood modification in which certain amino acid residues are phosphorylated by the action of protein kinases or dephosphorylated by the action of phosphatases. The acetylation of lysine residues is emerging as an analogous mechanism, in which non-histone proteins are acted on by acetylases and deacetylases.[19] It is in this context that HDACs are being found to interact with a variety of non-histone proteins—some of these are transcription factors and co-regulators, some are not. Note the following four examples:

- HDAC6 is associated with aggresomes. Misfolded protein aggregates are tagged by ubiquitination and removed from the cytoplasm by dynein motors via the microtubule network to an organelle termed the aggresome. HDAC 6 binds polyubiquitinated misfolded proteins and links to dynein motors, thereby allowing the misfolded protein cargo to be physically transported to chaperones and proteasomes for subsequent destruction.[20] HDAC6 is important regulator of HSP90 function and its inhibitor proposed to treat metabolic disorders.[21]

- PTEN is an important phosphatase involved in cell signaling via phosphoinositols and the AKT/PI3 kinase pathway. PTEN is subject to complex regulatory control via phosphorylation, ubiquitination, oxidation and acetylation. Acetylation of PTEN by the histone acetyltransferase p300/CBP-associated factor (PCAF) can repress its activity; on the converse, deacetylation of PTEN by SIRT1 deacetylase and, by HDAC1, can stimulate its activity.[22][23]

- APE1/Ref-1 (APEX1) is a multifunctional protein possessing both DNA repair activity (on abasic and single-strand break sites) and transcriptional regulatory activity associated with oxidative stress. APE1/Ref-1 is acetylated by PCAF; on the converse, it is stably associated with and deacetylated by Class I HDACs. The acetylation state of APE1/Ref-1 does not appear to affect its DNA repair activity, but it does regulate its transcriptional activity such as its ability to bind to the PTH promoter and initiate transcription of the parathyroid hormone gene.[24][25]

- NF-κB is a key transcription factor and effector molecule involved in responses to cell stress, consisting of a p50/p65 heterodimer. The p65 subunit is controlled by acetylation via PCAF and by deacetylation via HDAC3 and HDAC6.[26]

These are just some examples of constantly emerging non-histone, non-chromatin roles for HDACs.

HDAC inhibitors

[edit]Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDIs) have a long history of use in psychiatry and neurology as mood stabilizers and anti-epileptics, for example, valproic acid. In more recent times, HDIs are being studied as a mitigator or treatment for neurodegenerative diseases.[27][28][29] Also in recent years, there has been an effort to develop HDIs for cancer therapy.[30][31] Vorinostat (SAHA) was FDA approved in 2006 for the treatment of cutaneous manifestations in patients with cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) that have failed previous treatments. A second HDI, Istodax (romidepsin), was approved in 2009 for patients with CTCL. The exact mechanisms by which the compounds may work are unclear, but epigenetic pathways are proposed.[32] In addition, a clinical trial is studying valproic acid effects on the latent pools of HIV in infected persons.[33] HDIs are currently being investigated as chemosensitizers for cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation therapy, or in association with DNA methylation inhibitors based on in vitro synergy.[34] Isoform selective HDIs which can aid in elucidating role of individual HDAC isoforms have been developed.[35][36][37][29]

HDAC inhibitors have effects on non-histone proteins that are related to acetylation. HDIs can alter the degree of acetylation of these molecules and, therefore, increase or repress their activity. For the four examples given above (see Function) on HDACs acting on non-histone proteins, in each of those instances the HDAC inhibitor Trichostatin A (TSA) blocks the effect. HDIs have been shown to alter the activity of many transcription factors, including ACTR, cMyb, E2F1, EKLF, FEN 1, GATA, HNF-4, HSP90, Ku70, NFκB, PCNA, p53, RB, Runx, SF1 Sp3, STAT, TFIIE, TCF, and YY1.[38][39]

The ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate has been shown in mice to increase gene expression of FOXO3a by histone deacetylase inhibition.[40]

Histone deacetylase inhibitors may modulate the latency of some viruses, resulting in reactivation.[41] This has been shown to occur, for instance, with a latent human herpesvirus-6 infection.

Histone deacetylase inhibitors have shown activity against certain Plasmodium species and stages which may indicate they have potential in malaria treatment. It has been shown that HDIs accumulate acetylated histone H3K9/H3K14, a downstream target of class I HDACs.[42]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bottomley MJ, Lo Surdo P, Di Giovine P, Cirillo A, Scarpelli R, Ferrigno F, et al. (September 2008). "Structural and functional analysis of the human HDAC4 catalytic domain reveals a regulatory structural zinc-binding domain". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (39): 26694–26704. doi:10.1074/jbc.M803514200. PMC 3258910. PMID 18614528.

- ^ Seto, Edward; Yoshida, Minoru (2014-04-01). "Erasers of histone acetylation: the histone deacetylase enzymes". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 6 (4) a018713. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a018713. ISSN 1943-0264. PMC 3970420. PMID 24691964.

- ^ a b c Milazzo G, Mercatelli D, Di Muzio G, Triboli L, De Rosa P, Perini G, Giorgi FM (May 2020). "Histone Deacetylases (HDACs): Evolution, Specificity, Role in Transcriptional Complexes, and Pharmacological Actionability". Genes. 11 (5): 556–604. doi:10.3390/genes11050556. PMC 7288346. PMID 32429325.

- ^ Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, Nielsen ML, Rehman M, Walther TC, et al. (August 2009). "Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions". Science. 325 (5942): 834–840. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..834C. doi:10.1126/science.1175371. PMID 19608861. S2CID 206520776.

- ^ Chen, Hong Ping; Zhao, Yu Tina; Zhao, Ting C (2015). "Histone Deacetylases and Mechanisms of Regulation of Gene Expression (Histone deacetylases in cancer)". Crit Rev Oncog. 20 (1–2): 35–47. doi:10.1615/critrevoncog.2015012997. PMC 4809735. PMID 25746103.

- ^ Leipe DD, Landsman D (September 1997). "Histone deacetylases, acetoin utilization proteins and acetylpolyamine amidohydrolases are members of an ancient protein superfamily". Nucleic Acids Research. 25 (18): 3693–3697. doi:10.1093/nar/25.18.3693. PMC 146955. PMID 9278492.

- ^ Dokmanovic M, Clarke C, Marks PA (October 2007). "Histone deacetylase inhibitors: overview and perspectives". Molecular Cancer Research. 5 (10): 981–989. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-07-0324. PMID 17951399.

- ^ You SH, Lim HW, Sun Z, Broache M, Won KJ, Lazar MA (February 2013). "Nuclear receptor co-repressors are required for the histone-deacetylase activity of HDAC3 in vivo". Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 20 (2): 182–187. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2476. PMC 3565028. PMID 23292142.

- ^ Marks PA, Xu WS (July 2009). "Histone deacetylase inhibitors: Potential in cancer therapy". Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 107 (4): 600–608. doi:10.1002/jcb.22185. PMC 2766855. PMID 19459166.

- ^ Bürger M, Chory J (2018). "Structural and chemical biology of deacetylases for carbohydrates, proteins, small molecules and histones". Communications Biology. 1 217. doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0214-4. PMC 6281622. PMID 30534609.

- ^ Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L (February 2000). "Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase". Nature. 403 (6771): 795–800. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..795I. doi:10.1038/35001622. PMID 10693811. S2CID 2967911.

- ^ Yang XJ, Seto E (March 2008). "The Rpd3/Hda1 family of lysine deacetylases: from bacteria and yeast to mice and men". Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. 9 (3): 206–218. doi:10.1038/nrm2346. PMC 2667380. PMID 18292778.

- ^ Barneda-Zahonero B, Parra M (December 2012). "Histone deacetylases and cancer". Molecular Oncology. 6 (6): 579–589. doi:10.1016/j.molonc.2012.07.003. PMC 5528343. PMID 22963873.

- ^ de Ruijter AJ, van Gennip AH, Caron HN, Kemp S, van Kuilenburg AB (March 2003). "Histone deacetylases (HDACs): characterization of the classical HDAC family". The Biochemical Journal. 370 (Pt 3): 737–749. doi:10.1042/BJ20021321. PMC 1223209. PMID 12429021.

- ^ Longworth MS, Laimins LA (July 2006). "Histone deacetylase 3 localizes to the plasma membrane and is a substrate of Src". Oncogene. 25 (32): 4495–4500. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1209473. PMID 16532030.

- ^ Valenzuela-Fernández A, Cabrero JR, Serrador JM, Sánchez-Madrid F (June 2008). "HDAC6: a key regulator of cytoskeleton, cell migration and cell-cell interactions". Trends in Cell Biology. 18 (6): 291–297. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2008.04.003. PMID 18472263.

- ^ Zupkovitz G, Tischler J, Posch M, Sadzak I, Ramsauer K, Egger G, et al. (November 2006). "Negative and positive regulation of gene expression by mouse histone deacetylase 1". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 26 (21): 7913–7928. doi:10.1128/MCB.01220-06. PMC 1636735. PMID 16940178.

- ^ Sharma RP, Grayson DR, Gavin DP (January 2008). "Histone deactylase 1 expression is increased in the prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia subjects: analysis of the National Brain Databank microarray collection". Schizophrenia Research. 98 (1–3): 111–117. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.020. PMC 2254186. PMID 17961987.

- ^ Glozak MA, Sengupta N, Zhang X, Seto E (December 2005). "Acetylation and deacetylation of non-histone proteins". Gene. 363: 15–23. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.010. PMID 16289629.

- ^ Rodriguez-Gonzalez A, Lin T, Ikeda AK, Simms-Waldrip T, Fu C, Sakamoto KM (April 2008). "Role of the aggresome pathway in cancer: targeting histone deacetylase 6-dependent protein degradation". Cancer Research. 68 (8): 2557–2560. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5989. PMID 18413721.

- ^ Mahla RS (July 2012). "Comment on: Winkler et al. Histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) is an essential modifier of glucocorticoid-induced hepatic gluconeogenesis. Diabetes 2012;61:513-523". Diabetes. 61 (7): e10, author reply e11. doi:10.2337/db12-0323. PMC 3379673. PMID 22723278.

- ^ Ikenoue T, Inoki K, Zhao B, Guan KL (September 2008). "PTEN acetylation modulates its interaction with PDZ domain". Cancer Research. 68 (17): 6908–6912. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1107. PMID 18757404.

- ^ Yao XH, Nyomba BL (June 2008). "Hepatic insulin resistance induced by prenatal alcohol exposure is associated with reduced PTEN and TRB3 acetylation in adult rat offspring". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 294 (6): R1797 – R1806. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00804.2007. PMID 18385463.

- ^ Bhakat KK, Izumi T, Yang SH, Hazra TK, Mitra S (December 2003). "Role of acetylated human AP-endonuclease (APE1/Ref-1) in regulation of the parathyroid hormone gene". The EMBO Journal. 22 (23): 6299–6309. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg595. PMC 291836. PMID 14633989.

- ^ Fantini D, Vascotto C, Deganuto M, Bivi N, Gustincich S, Marcon G, et al. (January 2008). "APE1/Ref-1 regulates PTEN expression mediated by Egr-1". Free Radical Research. 42 (1): 20–29. doi:10.1080/10715760701765616. PMC 2677450. PMID 18324520.

- ^ Hasselgren PO (December 2007). "Ubiquitination, phosphorylation, and acetylation--triple threat in muscle wasting". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 213 (3): 679–689. doi:10.1002/jcp.21190. PMID 17657723.

- ^ Hahnen E, Hauke J, Tränkle C, Eyüpoglu IY, Wirth B, Blümcke I (February 2008). "Histone deacetylase inhibitors: possible implications for neurodegenerative disorders". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 17 (2): 169–184. doi:10.1517/13543784.17.2.169. PMID 18230051. S2CID 14344174.

- ^ "Scientists 'reverse' memory loss". BBC News. 2007-04-29. Retrieved 2007-07-08.

- ^ a b Geurs S, Clarisse D, Baele F, Franceus J, Desmet T, De Bosscher K, D'hooghe M (May 2022). "Identification of mercaptoacetamide-based HDAC6 inhibitors via a lean inhibitor strategy: screening, synthesis, and biological evaluation". Chemical Communications. 58 (42): 6239–6242. doi:10.1039/D2CC01550A. hdl:1854/LU-8752799. PMID 35510683. S2CID 248527466.

- ^ Mwakwari SC, Patil V, Guerrant W, Oyelere AK (2010). "Macrocyclic histone deacetylase inhibitors". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 10 (14): 1423–1440. doi:10.2174/156802610792232079. PMC 3144151. PMID 20536416.

- ^ Miller TA, Witter DJ, Belvedere S (November 2003). "Histone deacetylase inhibitors". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 46 (24): 5097–5116. doi:10.1021/jm0303094. PMID 14613312.

- ^ Monneret C (April 2007). "Histone deacetylase inhibitors for epigenetic therapy of cancer". Anti-Cancer Drugs. 18 (4): 363–370. doi:10.1097/CAD.0b013e328012a5db. PMID 17351388. S2CID 39017666.

- ^ Depletion of Latent HIV in CD4 Cells - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov

- ^ Batty N, Malouf GG, Issa JP (August 2009). "Histone deacetylase inhibitors as anti-neoplastic agents". Cancer Letters. 280 (2): 192–200. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2009.03.013. PMID 19345475.

- ^ Patil V, Sodji QH, Kornacki JR, Mrksich M, Oyelere AK (May 2013). "3-Hydroxypyridin-2-thione as novel zinc binding group for selective histone deacetylase inhibition". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 56 (9): 3492–3506. doi:10.1021/jm301769u. PMC 3657749. PMID 23547652.

- ^ Mwakwari SC, Guerrant W, Patil V, Khan SI, Tekwani BL, Gurard-Levin ZA, et al. (August 2010). "Non-peptide macrocyclic histone deacetylase inhibitors derived from tricyclic ketolide skeleton". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 53 (16): 6100–6111. doi:10.1021/jm100507q. PMC 2924451. PMID 20669972.

- ^ Butler KV, Kalin J, Brochier C, Vistoli G, Langley B, Kozikowski AP (August 2010). "Rational design and simple chemistry yield a superior, neuroprotective HDAC6 inhibitor, tubastatin A". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 132 (31): 10842–10846. Bibcode:2010JAChS.13210842B. doi:10.1021/ja102758v. PMC 2916045. PMID 20614936.

- ^ Drummond DC, Noble CO, Kirpotin DB, Guo Z, Scott GK, Benz CC (2005). "Clinical development of histone deacetylase inhibitors as anticancer agents". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 45: 495–528. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095825. PMID 15822187.

- ^ Yang XJ, Seto E (August 2007). "HATs and HDACs: from structure, function and regulation to novel strategies for therapy and prevention". Oncogene. 26 (37): 5310–5318. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1210599. PMID 17694074.

- ^ Shimazu T, Hirschey MD, Newman J, He W, Shirakawa K, Le Moan N, et al. (January 2013). "Suppression of oxidative stress by β-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor". Science. 339 (6116): 211–214. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..211S. doi:10.1126/science.1227166. PMC 3735349. PMID 23223453.

- ^ Arbuckle JH, Medveczky PG (August 2011). "The molecular biology of human herpesvirus-6 latency and telomere integration". Microbes and Infection. 13 (8–9): 731–741. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2011.03.006. PMC 3130849. PMID 21458587.

- ^ Beus M, Rajić Z, Maysinger D, Mlinarić Z, Antunović M, Marijanović I, et al. (August 2018). "SAHAquines, Novel Hybrids Based on SAHA and Primaquine Motifs, as Potential Cytostatic and Antiplasmodial Agents". ChemistryOpen. 7 (8): 624–638. doi:10.1002/open.201800117. PMC 6104433. PMID 30151334.

External links

[edit]- Histone+deacetylase at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Animation at Merck