Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

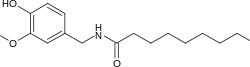

Capsaicin

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /kæpˈseɪsɪn/ or /kæpˈseɪəsɪn/ |

| Preferred IUPAC name

(6E)-N-[(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-8-methylnon-6-enamide | |

| Other names

(E)-N-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzyl)-8-methylnon-6-enamide

8-Methyl-N-vanillyl-trans-6-nonenamide trans-8-Methyl-N-vanillylnon-6-enamide (E)-Capsaicin Capsicine Capsicin CPS | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 2816484 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.337 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C18H27NO3 | |

| Molar mass | 305.418 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Crystalline white powder[1] |

| Odor | Highly pungent |

| Melting point | 62 to 65 °C (144 to 149 °F; 335 to 338 K) |

| Boiling point | 210 to 220 °C (410 to 428 °F; 483 to 493 K) 0.01 Torr |

| 0.0013 g/100 mL | |

| Solubility | |

| Vapor pressure | 1.32×10−8 mm Hg at 25 °C[2] |

| UV-vis (λmax) | 280 nm |

| Structure | |

| Monoclinic | |

| Pharmacology | |

| M02AB01 (WHO) N01BX04 (WHO) | |

| License data | |

| Legal status | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H301, H302, H315, H318 | |

| P264, P270, P280, P301+P310, P301+P312, P302+P352, P305+P351+P338, P310, P321, P330, P332+P313, P362, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | [2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

| Capsaicin | |

|---|---|

| Heat | Above peak[2] |

| Scoville scale | 16,000,000[5] SHU |

Capsaicin (8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide) (/kæpˈseɪ.ə.sɪn/, rarely /kæpˈseɪsɪn/)[6][7][8] is an active component of chili peppers, which are plants belonging to the genus Capsicum. It is a potent irritant for mammals, including humans, for which it produces a sensation of burning in any tissue with which it comes into contact. Capsaicin and several related amides (capsaicinoids) are produced as secondary metabolites by chili peppers, likely as deterrents against eating by mammals and against the growth of fungi.[9] Pure capsaicin is a hydrophobic, colorless, highly pungent (i.e., spicy) crystalline solid.[2][10][11]

Natural function

[edit]Capsaicin is present in large quantities in the placental tissue (which holds the seeds), the internal membranes and, to a lesser extent, the other fleshy parts of the fruits of plants in the genus Capsicum. The seeds themselves do not produce any capsaicin, although the highest concentration of capsaicin can be found in the white pith of the inner wall, where the seeds are attached.[12]

The seeds of Capsicum plants are dispersed predominantly by birds. In birds, the TRPV1 channel does not respond to capsaicin or related chemicals, but mammalian TRPV1 is very sensitive to it. This is advantageous to the plant, as chili pepper seeds consumed by birds pass through the digestive tract and can germinate later, whereas mammals have molar teeth that destroy such seeds and prevent them from germinating. Thus, natural selection may have led to increasing capsaicin production because it makes the plant less likely to be eaten by animals that do not help it disperse.[13] There is also evidence that capsaicin may have evolved as an anti-fungal agent.[14] The fungal pathogen Fusarium, which is known to infect wild chilies and thereby reduce seed viability, is deterred by capsaicin, which thus limits this form of predispersal seed mortality.

The vanillotoxin-containing venom of a certain tarantula species (Psalmopoeus cambridgei) activates the same pathway of pain as is activated by capsaicin. It is an example of a shared pathway in both plant and animal anti-mammalian defense.[15]

Uses

[edit]Food

[edit]

Because of the burning sensation caused by capsaicin when it comes in contact with mucous membranes, it is commonly used in food products to provide added spiciness or "heat" (piquancy), usually in the form of spices such as chili powder and paprika.[16] In high concentrations, capsaicin will also cause a burning effect on other sensitive areas, such as skin or eyes.[17] The degree of heat found within a food is often measured on the Scoville scale.[16]

There has long been a demand for capsaicin-spiced products like chili pepper, and hot sauces such as Tabasco sauce and Mexican salsa.[16] It is common for people to experience pleasurable and even euphoric effects from ingesting capsaicin.[16] Folklore among self-described "chiliheads" attribute this to pain-stimulated release of endorphins, a different mechanism from the local receptor overload that makes capsaicin effective as a topical analgesic.[17]

Research and pharmaceutical use

[edit]Capsaicin is used as an analgesic in topical ointments and dermal patches to relieve pain, typically in concentrations between 0.025% and 0.1%.[18] It may be applied in cream form for the temporary relief of minor aches and pains of muscles and joints associated with arthritis, backache, strains and sprains, often in compounds with other rubefacients.[18]

It is also used to reduce the symptoms of peripheral neuropathy, such as post-herpetic neuralgia caused by shingles.[18] A capsaicin transdermal patch (Qutenza) for the management of this particular therapeutic indication (pain due to post-herpetic neuralgia) was approved in 2009, as a therapeutic by both the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)[19][20] and the European Union.[21] A subsequent application to the FDA for Qutenza to be used as an analgesic in HIV neuralgia was refused.[22] One 2017 review of clinical studies found, with limited quality, that high-dose topical capsaicin (8%) compared with control (0.4% capsaicin) provided moderate to substantial pain relief from post-herpetic neuralgia, HIV-neuropathy, and diabetic neuropathy.[23]

Although capsaicin creams have been used to treat psoriasis for reduction of itching,[18][24][25] a review of six clinical trials involving topical capsaicin for treatment of pruritus concluded there was insufficient evidence of effect.[26] Oral capsaicin decreases LDL cholesterol levels moderately.[27]

There is insufficient clinical evidence to determine the role of ingested capsaicin on several human disorders, including obesity, diabetes, cancer and cardiovascular diseases.[18]

Pepper spray and pests

[edit]Capsaicinoids are also an active ingredient in riot control and personal defense pepper spray agents.[2] When the spray comes in contact with skin, especially eyes or mucous membranes, it produces pain and breathing difficulty in the affected individual.[2]

Capsaicin is also used to deter pests, specifically mammalian pests. Targets of capsaicin repellants include voles, deer, rabbits, squirrels, bears, insects, and attacking dogs.[28] Ground or crushed dried chili pods may be used in birdseed to deter rodents,[29] taking advantage of the insensitivity of birds to capsaicin. The Elephant Pepper Development Trust claims that using chili peppers as a barrier crop can be a sustainable means for rural African farmers to deter elephants from eating their crops.[30]

An article published in the Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B in 2006 states that "Although hot chili pepper extract is commonly used as a component of household and garden insect-repellent formulas, it is not clear that the capsaicinoid elements of the extract are responsible for its repellency."[31]

The first pesticide product using solely capsaicin as the active ingredient was registered with the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1962.[28]

Equestrian sports

[edit]Capsaicin is a banned substance in equestrian sports because of its hypersensitizing and pain-relieving properties.[32] At the show jumping events of the 2008 Summer Olympics, four horses tested positive for capsaicin, which resulted in disqualification.[32]

Irritant effects

[edit]Acute health effects

[edit]Capsaicin is a strong irritant requiring proper protective goggles, respirators, and proper hazardous material-handling procedures. Capsaicin takes effect upon skin contact (irritant, sensitizer), eye contact (irritant), ingestion, and inhalation (lung irritant, lung sensitizer). The LD50 in mice is 47.2 mg/kg.[33][34]

Painful exposures to capsaicin-containing peppers are among the most common plant-related exposures presented to poison centers.[35] They cause burning or stinging pain to the skin and, if ingested in large amounts by adults or small amounts by children, can produce nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and burning diarrhea. Eye exposure produces intense tearing, pain, conjunctivitis, and blepharospasm.[36]

Treatment after exposure

[edit]The primary treatment is removal of the offending substance. Plain water is ineffective at removing capsaicin.[33] Capsaicin is soluble in alcohol, which can be used to clean contaminated items.[33]

When capsaicin is ingested, cold milk may be an effective way to relieve the burning sensation due to caseins in milk, and the water of milk acts as a surfactant, allowing the capsaicin to form an emulsion with it.[37]

Weight loss and regain

[edit]As of 2007, there was no evidence showing that weight loss is directly correlated with ingesting capsaicin. Well-designed clinical research had not been performed because the pungency of capsaicin in prescribed doses under research prevented subjects from complying in the study.[38] A 2014 meta-analysis of further trials found weak evidence that consuming capsaicin before a meal might slightly reduce the amount of food consumed, and might drive food preference toward carbohydrates.[39]

Peptic ulcer

[edit]One 2006 review concluded that capsaicin may relieve symptoms of a peptic ulcer rather than being a cause of it.[40]

Death

[edit]Ingestion of high quantities of capsaicin can be deadly,[41] particularly in people with heart problems.[42] Even healthy young people can suffer adverse health effects like myocardial infarction after ingestion of capsaicin capsules.[43]

Mechanism of action

[edit]The burning and painful sensations associated with capsaicin result from "defunctionalization" of nociceptor nerve fibers by causing a topical hypersensitivity reaction in the skin.[2][44] As a member of the vanilloid family, capsaicin binds to a receptor on nociceptor fibers called the vanilloid receptor subtype 1 (TRPV1).[44][45][46] TRPV1, which can also be stimulated with heat, protons, and physical abrasion, permits cations to pass through the cell membrane when activated.[44] The resulting depolarization of the neuron stimulates it to send impulses to the brain.[44] By binding to TRPV1 receptors, capsaicin produces similar sensations to those of excessive heat or abrasive damage, such as warming, tingling, itching, or stinging, explaining why capsaicin is described as an irritant on the skin and eyes or by ingestion.[44]

Clarifying the mechanisms of capsaicin effects on skin nociceptors was part of awarding the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, as it led to the discovery of skin sensors for temperature and touch, and identification of the single gene causing sensitivity to capsaicin.[47][48]

History

[edit]The compound was first extracted in impure form in 1816 by Christian Friedrich Bucholz (1770–1818).[49][a] In 1873 German pharmacologist Rudolf Buchheim[59][60][61] (1820–1879) and in 1878 the Hungarian doctor Endre Hőgyes[62][63] stated that "capsicol" (partially purified capsaicin[64]) caused the burning feeling when in contact with mucous membranes and increased secretion of gastric acid.

Capsaicinoids

[edit]The most commonly occurring capsaicinoids are capsaicin (69%), dihydrocapsaicin (22%), nordihydrocapsaicin (7%), homocapsaicin (1%), and homodihydrocapsaicin (1%).[65]

Capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin (both 16.0 million SHU) are the most pungent capsaicinoids. Nordihydrocapsaicin (9.1 million SHU), homocapsaicin and homodihydrocapsaicin (both 8.6 million SHU) are about half as hot.[5]

There are six natural capsaicinoids (table below). Although vanillylamide of n-nonanoic acid (Nonivamide, VNA, also PAVA) is produced synthetically for most applications, it does occur naturally in Capsicum species.[66]

| Capsaicinoid name | Abbrev. | Typical relative amount |

Scoville heat units |

Chemical structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capsaicin | CPS | 69% | 16,000,000 |

|

| Dihydrocapsaicin | DHC | 22% | 16,000,000 |

|

| Nordihydrocapsaicin | NDHC | 7% | 9,100,000 |

|

| Homocapsaicin | HC | 1% | 8,600,000 |

|

| Homodihydrocapsaicin | HDHC | 1% | 8,600,000 |

|

| Nonivamide | PAVA | 9,200,000 |

|

Biosynthesis

[edit]

History

[edit]The general biosynthetic pathway of capsaicin and other capsaicinoids was elucidated in the 1960s by Bennett and Kirby, and Leete and Louden. Radiolabeling studies identified phenylalanine and valine as the precursors to capsaicin.[67][68] Enzymes of the phenylpropanoid pathway, phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H), caffeic acid O-methyltransferase (COMT) and their function in capsaicinoid biosynthesis were identified later by Fujiwake et al.,[69][70] and Sukrasno and Yeoman.[71] Suzuki et al. are responsible for identifying leucine as another precursor to the branched-chain fatty acid pathway.[72] It was discovered in 1999 that pungency of chili peppers is related to higher transcription levels of key enzymes of the phenylpropanoid pathway, phenylalanine ammonia lyase, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase, caffeic acid O-methyltransferase. Similar studies showed high transcription levels in the placenta of chili peppers with high pungency of genes responsible for branched-chain fatty acid pathway.[73]

Biosynthetic pathway

[edit]Plants exclusively of the genus Capsicum produce capsaicinoids, which are alkaloids.[74] Capsaicin is believed to be synthesized in the interlocular septum of chili peppers and depends on the gene AT3, which resides at the pun1 locus, and which encodes a putative acyltransferase.[75]

Biosynthesis of the capsaicinoids occurs in the glands of the pepper fruit where capsaicin synthase condenses vanillylamine from the phenylpropanoid pathway with an acyl-CoA moiety produced by the branched-chain fatty acid pathway.[68][76][77][78]

Capsaicin is the most abundant capsaicinoid found in the genus Capsicum, but at least ten other capsaicinoid variants exist.[79] Phenylalanine supplies the precursor to the phenylpropanoid pathway while leucine or valine provide the precursor for the branched-chain fatty acid pathway.[68][76] To produce capsaicin, 8-methyl-6-nonenoyl-CoA is produced by the branched-chain fatty acid pathway and condensed with vanillylamine. Other capsaicinoids are produced by the condensation of vanillylamine with various acyl-CoA products from the branched-chain fatty acid pathway, which is capable of producing a variety of acyl-CoA moieties of different chain length and degrees of unsaturation.[80] All condensation reactions between the products of the phenylpropanoid and branched-chain fatty acid pathway are mediated by capsaicin synthase to produce the final capsaicinoid product.[68][76]

Evolution

[edit]The Capsicum genus split from Solanaceae 19.6 million years ago, 5.4 million years after the appearance of Solanaceae, and is native only to the Americas.[81] Chilies only started to quickly evolve in the past 2 million years into markedly different species. This evolution can be partially attributed to a key compound found in peppers, 8-methyl-N-vanillyl-6-nonenamide, otherwise known as capsaicin. Capsaicin evolved similarly across species of chilies that produce capsaicin. Its evolution over the course of centuries is due to genetic drift and natural selection, across the genus Capsicum. Despite the fact that chilies within the Capsicum genus are found in diverse environments, the capsaicin found within them all exhibit similar properties that serve as defensive and adaptive features. Capsaicin evolved to preserve the fitness of peppers against fungi infections, insects, and granivorous mammals.[82]

Antifungal properties

[edit]Capsaicin acts as an antifungal agent in four primary ways. First, capsaicin inhibits the metabolic rate of the cells that make up the fungal biofilm.[83] This inhibits the area and growth rate of the fungus, since the biofilm creates an area where a fungus can grow and adhere to the chili in which capsaicin is present.[84] Capsaicin also inhibits fungal hyphae formation, which impacts the amount of nutrients that the rest of the fungal body can receive.[85] Thirdly, capsaicin disrupts the structure[86] of fungal cells and the fungal cell membranes. This has consequential negative impacts on the integrity of fungal cells and their ability to survive and proliferate. Additionally, the ergosterol synthesis of growing fungi decreases in relation to the amount of capsaicin present in the growth area. This impacts the fungal cell membrane, and how it is able to reproduce and adapt to stressors in its environment.[87]

Insecticidal properties

[edit]Capsaicin deters insects in multiple ways. The first is by deterring insects from laying their eggs on the pepper due to the effects capsaicin has on these insects.[88] Capsaicin can cause intestinal dysplasia upon ingestion, disrupting insect metabolism and causing damage to cell membranes within the insect.[89][90] This in turn disrupts the standard feeding response of insects.

Seed dispersion and deterrents against granivorous mammals

[edit]Granivorous mammals pose a risk to the propagation of chilies because their molars grind the seeds of chilies, rendering them unable to grow into new chili plants.[91][13] As a result, modern chilies evolved defense mechanisms to mitigate the risk of granivorous mammals. While capsaicin is present at some level in every part of the pepper, the chemical has its highest concentration in the tissue near the seeds within chilies.[12] Birds are able to eat chilies, then disperse the seeds in their excrement, enabling propagation.[13]

Adaptation to varying moisture levels

[edit]Capsaicin is a potent defense mechanism for chilies, but it does come at a cost. Varying levels of capsaicin in chilies currently appear to be caused by an evolutionary split between surviving in dry environments, and having defense mechanisms against fungal growth, insects, and granivorous mammals.[92] Capsaicin synthesis in chilies places a strain on their water resources.[93] This directly affects their fitness, as it has been observed that standard concentration of capsaicin of peppers in high moisture environments in the seeds and pericarps of the peppers reduced the seeds production by 50%.[94]

See also

[edit]- Allicin, the active piquant flavor chemical in uncooked garlic, and to a lesser extent onions (see those articles for discussion of other chemicals in them relating to pungency, and eye irritation)

- Capsazepine, capsaicin antagonist

- Iodoresiniferatoxin, an ultrapotent capsaicin antagonist derived from Resiniferatoxin

- Naga Viper pepper, Bhut Jolokia Pepper, Carolina Reaper, Trinidad Moruga Scorpion; some of the world's most capsaicin-rich fruits

- Piperine, the active flavor chemical in black pepper

- List of capsaicinoids

References

[edit]- ^ "Capsaicin". ChemSpider. Royal Society of Chemistry. 2018. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Capsaicin". PubChem, US National Library of Medicine. 27 May 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ "Qutenza- capsaicin kit". DailyMed. 10 January 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Qutenza (capsaicin) NDA #022395". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 3 October 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2023.[dead link]

- ^ a b Govindarajan VS, Sathyanarayana MN (1991). "Capsicum—production, technology, chemistry, and quality. Part V. Impact on physiology, pharmacology, nutrition, and metabolism; structure, pungency, pain, and desensitization sequences". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 29 (6): 435–474. doi:10.1080/10408399109527536. PMID 2039598.

- ^ "Capsaicin".

- ^ "Definition of CAPSAICIN".

- ^ "The American Heritage Dictionary entry: Capsaicin".

- ^ "What Made Chili Peppers So Spicy?". Talk of the Nation. 15 August 2008.

- ^ David WI, Shankland K, Shankland K, Shankland N (1998). "Routine determination of molecular crystal structures from powder diffraction data". Chemical Communications (8): 931–932. doi:10.1039/a800855h.

- ^ Lozinšek M (1 April 2025). "Single-crystal structure of the spicy capsaicin". Acta Crystallographica Section C Structural Chemistry. 81 (4): 188–192. Bibcode:2025AcCrC..81..188L. doi:10.1107/S2053229625001706. ISSN 2053-2296. PMC 11970115. PMID 40052876.

- ^ a b "Chile Information – Frequently Asked Questions". New Mexico State University – College of Agriculture and Home Economics. 2005. Archived from the original on 4 May 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2007.

- ^ a b c Tewksbury JJ, Nabhan GP (July 2001). "Seed dispersal. Directed deterrence by capsaicin in chilies". Nature. 412 (6845): 403–404. Bibcode:2001Natur.412..403T. doi:10.1038/35086653. PMID 11473305. S2CID 4389051.

- ^ Tewksbury JJ, Reagan KM, Machnicki NJ, Carlo TA, Haak DC, Peñaloza AL, et al. (August 2008). "Evolutionary ecology of pungency in wild chilies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (33): 11808–11811. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511808T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0802691105. PMC 2575311. PMID 18695236.

- ^ Siemens J, Zhou S, Piskorowski R, Nikai T, Lumpkin EA, Basbaum AI, et al. (November 2006). "Spider toxins activate the capsaicin receptor to produce inflammatory pain". Nature. 444 (7116): 208–212. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..208S. doi:10.1038/nature05285. PMID 17093448. S2CID 4387600.

- ^ a b c d Gorman J (20 September 2010). "A Perk of Our Evolution: Pleasure in Pain of Chilies". New York Times. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ^ a b Rollyson WD, Stover CA, Brown KC, Perry HE, Stevenson CD, McNees CA, et al. (December 2014). "Bioavailability of capsaicin and its implications for drug delivery". Journal of Controlled Release. 196: 96–105. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.09.027. PMC 4267963. PMID 25307998.

- ^ a b c d e Fattori V, Hohmann MS, Rossaneis AC, Pinho-Ribeiro FA, Verri WA (June 2016). "Capsaicin: Current Understanding of Its Mechanisms and Therapy of Pain and Other Pre-Clinical and Clinical Uses". Molecules. 21 (7): 844. doi:10.3390/molecules21070844. PMC 6273101. PMID 27367653.

- ^ "FDA Approves New Drug Treatment for Long-Term Pain Relief after Shingles Attacks" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 17 November 2009. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Qutenza (capsaicin) NDA #022395". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 29 June 2010. Retrieved 19 August 2020.[dead link]

- "Application Number: 22-395: Summary Review" (PDF). FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 13 November 2009.

- ^ "Qutenza EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Hitt E (9 March 2012). "FDA Turns Down Capsaicin Patch for Painful Neuropathy in HIV". Medscape Medical News, WebMD. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- ^ Derry S, Rice AS, Cole P, Tan T, Moore RA (January 2017). "Topical capsaicin (high concentration) for chronic neuropathic pain in adults" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1) CD007393. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007393.pub4. hdl:10044/1/49554. PMC 6464756. PMID 28085183. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- ^ Glinski W, Glinska-Ferenz M, Pierozynska-Dubowska M (1991). "Neurogenic inflammation induced by capsaicin in patients with psoriasis". Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 71 (1): 51–54. doi:10.2340/00015555715154. PMID 1711752. S2CID 29307090.

- ^ Ellis CN, Berberian B, Sulica VI, Dodd WA, Jarratt MT, Katz HI, et al. (September 1993). "A double-blind evaluation of topical capsaicin in pruritic psoriasis". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 29 (3): 438–442. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70208-B. PMID 7688774.

- ^ Gooding SM, Canter PH, Coelho HF, Boddy K, Ernst E (August 2010). "Systematic review of topical capsaicin in the treatment of pruritus". International Journal of Dermatology. 49 (8): 858–865. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04537.x. PMID 21128913. S2CID 24484878.

- ^ Kelava L, Nemeth D, Hegyi P, Keringer P, Kovacs DK, Balasko M, et al. (April 2021). "Dietary supplementation of transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 channel agonists reduces serum total cholesterol level: a meta-analysis of controlled human trials". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 62 (25): 7025–7035. doi:10.1080/10408398.2021.1910138. PMID 33840333.

- ^ a b "R.E.D. Facts for Capsaicin" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ Jensen PG, Curtis PD, Dunn JA, Austic RE, Richmond ME (September 2003). "Field evaluation of capsaicin as a rodent aversion agent for poultry feed". Pest Management Science. 59 (9): 1007–1015. Bibcode:2003PMSci..59.1007J. doi:10.1002/ps.705. PMID 12974352.

- ^ "Human Elephant Conflict and Chilli Pepper". Elephant Pepper. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Antonious GF, Meyer JE, Snyder JC (2006). "Toxicity and repellency of hot pepper extracts to spider mite, Tetranychus urticae Koch". Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B. 41 (8): 1383–1391. Bibcode:2006JESHB..41.1383A. doi:10.1080/0360123060096419. PMID 17090499. S2CID 19121573.

- ^ a b "Olympic horses fail drugs tests". BBC News Online. 21 August 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ a b c "Capsaicin Material Safety Data Sheet". sciencelab.com. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- ^ Johnson W (2007). "Final report on the safety assessment of capsicum annuum extract, capsicum annuum fruit extract, capsicum annuum resin, capsicum annuum fruit powder, capsicum frutescens fruit, capsicum frutescens fruit extract, capsicum frutescens resin, and capsaicin". International Journal of Toxicology. 26 (Suppl 1): 3–106. doi:10.1080/10915810601163939. PMID 17365137. S2CID 208154058.

- ^ Krenzelok EP, Jacobsen TD (August 1997). "Plant exposures ... a national profile of the most common plant genera". Veterinary and Human Toxicology. 39 (4): 248–249. PMID 9251180.

- ^ Goldfrank LR, ed. (23 March 2007). Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 1167. ISBN 978-0-07-144310-4.

- ^ Senese F (23 February 2018). "Fire and Spice". General Chemistry Online. Department of Chemistry, Frostburg State University. Archived from the original on 29 April 1999. Retrieved 4 October 2021.

- ^ Diepvens K, Westerterp KR, Westerterp-Plantenga MS (January 2007). "Obesity and thermogenesis related to the consumption of caffeine, ephedrine, capsaicin, and green tea". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 292 (1): R77 – R85. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00832.2005. PMID 16840650. S2CID 7529851.

- ^ Whiting S, Derbyshire EJ, Tiwari B (February 2014). "Could capsaicinoids help to support weight management? A systematic review and meta-analysis of energy intake data". Appetite. 73: 183–188. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2013.11.005. PMID 24246368. S2CID 30252935.

- ^ Satyanarayana MN (2006). "Capsaicin and gastric ulcers". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 46 (4): 275–328. doi:10.1080/1040-830491379236. PMID 16621751. S2CID 40023195.

- ^ "The Health Risks of Eating Extremely Spicy Foods". Cleveland Clinic. 12 March 2023.

- ^ "Teen died from eating a spicy chip as part of social media challenge, autopsy report concludes". AP News. 16 May 2024.

- ^ Sogut O, Kaya H, Gokdemir MT, Sezen Y (January 2012). "Acute myocardial infarction and coronary vasospasm associated with the ingestion of cayenne pepper pills in a 25-year-old male". International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 5 5. doi:10.1186/1865-1380-5-5. PMC 3284873. PMID 22264348.

- ^ a b c d e "Capsaicin". DrugBank. 4 January 2023. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ Story GM, Crus-Orengo L (July–August 2007). "Feel the burn". American Scientist. 95 (4): 326–333. doi:10.1511/2007.66.326.

- ^ Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D (October 1997). "The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway". Nature. 389 (6653): 816–824. Bibcode:1997Natur.389..816C. doi:10.1038/39807. PMID 9349813. S2CID 7970319.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2021". Nobel Prize Outreach. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ Santora M, Engelbrecht C (4 October 2021). "Nobel Prize Awarded to Scientists for Research About Temperature and Touch". The New York Times.

- ^ Bucholz CF (1816). "Chemische Untersuchung der trockenen reifen spanischen Pfeffers" [Chemical investigation of dry, ripe Spanish peppers]. Almanach oder Taschenbuch für Scheidekünstler und Apotheker [Almanac or Pocketbook for Analysts and Apothecaries]. Vol. 37. Weimar. pp. 1–30. [Note: Christian Friedrich Bucholz's surname has been variously spelled as "Bucholz", "Bucholtz", or "Buchholz".]

- ^ In a series of articles, J. C. Thresh obtained capsaicin in almost pure form:

- Thresh JC (1876). "Isolation of capsaicin". The Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions. 3rd Series. 6: 941–947.

- Thresh JC (8 July 1876). "Capsaicin, the active principle in Capsicum fruits". The Pharmaceutical Journal and Transactions. 3rd Series. 7 (315): 21. [Note: This article is summarized in: "Capsaicin, the active principle in Capsicum fruits". The Analyst. 1 (8): 148–149. 1876. Bibcode:1876Ana.....1..148.. doi:10.1039/an876010148b.

- Year Book of Pharmacy… (1876), pages 250 and 543;

- Thresh JC (1877). "Note on Capsaicin". Year Book of Pharmacy: 24–25.

- Thresh JC (1877). "Report on the active principle of Cayenne pepper". Year Book of Pharmacy: 485–488.

- ^ Obituary notice of J. C. Thresh: "John Clough Thresh, M.D., D.Sc., D.P.H". British Medical Journal. 1 (3726): 1057–1058. June 1932. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.3726.1057-c. PMC 2521090. PMID 20776886.

- ^ King J, Felter HW, Lloys JU (1905). A King's American Dispensatory. Eclectic Medical Publications. ISBN 1-888483-02-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)) - ^ Micko K (1898). "Zur Kenntniss des Capsaïcins" [On our knowledge of capsaicin]. Zeitschrift für Untersuchung der Nahrungs- und Genussmittel (in German). 1 (12): 818–829. doi:10.1007/bf02529190.

- ^ Micko K (1899). "Über den wirksamen Bestandtheil des Cayennespfeffers" [On the active component of Cayenne pepper]. Zeitschrift für Untersuchung der Nahrungs- und Genussmittel (in German). 2 (5): 411–412. doi:10.1007/bf02529197.

- ^ Nelson EK (1919). "The constitution of capsaicin, the pungent principle of capsicum". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 41 (7): 1115–1121. Bibcode:1919JAChS..41.1115N. doi:10.1021/ja02228a011.

- ^ Späth E, Darling SF (1930). "Synthese des Capsaicins". Chem. Ber. 63B (3): 737–743. doi:10.1002/cber.19300630331.

- ^ Kosuge S, Inagaki Y, Okumura H (1961). "Studies on the pungent principles of red pepper. Part VIII. On the chemical constitutions of the pungent principles". Nippon Nogeikagaku Kaishi [Journal of the Agricultural Chemical Society of Japan] (in Japanese). 35: 923–927. doi:10.1271/nogeikagaku1924.35.10_923.

- ^ Kosuge S, Inagaki Y (1962). "Studies on the pungent principles of red pepper. Part XI. Determination and contents of the two pungent principles". Nippon Nogeikagaku Kaishi [Journal of the Agricultural Chemical Society of Japan] (in Japanese). 36: 251. doi:10.1271/nogeikagaku1924.36.251.

- ^ Buchheim R (1873). "Über die 'scharfen' Stoffe" [On the "hot" substance]. Archiv der Heilkunde [Archive of Medicine]. 14.

- ^ Buchheim R (1872). "Fructus Capsici". Vierteljahresschrift für praktische Pharmazie [Quarterly Journal for Practical Pharmacy] (in German). 4: 507ff.

- ^ Buchheim R (1873). "Fructus Capsici". Proceedings of the American Pharmaceutical Association. 22: 106.

- ^ Hőgyes E (1877). "Adatok a Capsicum annuum (paprika) alkatrészeinek élettani hatásához" [Data on the physiological effects of the pepper (Capsicum annuum)]. Orvos-természettudumányi társulatot Értesítője [ulletin of the Medical Science Association] (in Hungarian).

- ^ Högyes A (June 1878). "Mittheilungen aus dem Institute für allgemeine Pathologie und Pharmakologie an der Universität zu Klausenburg". Archiv für experimentelle Pathologie und Pharmakologie. 9 (1–2): 117–130. doi:10.1007/BF02125956. S2CID 32414315.

- ^ Flückiger FA (1891). Pharmakognosie des Pflanzenreiches. Berlin, Germany: Gaertner's Verlagsbuchhandlung.

- ^ Bennett DJ, Kirby GW (1968). "Constitution and biosynthesis of capsaicin". J. Chem. Soc. C: 442. doi:10.1039/j39680000442.

- ^ Constant HL, Cordell GA, West DP (April 1996). "Nonivamide, a Constituent of Capsicum oleoresin". Natural Products. 59 (4): 425–426. Bibcode:1996JNAtP..59..425C. doi:10.1021/np9600816.

- ^ Bennett DJ, Kirby GW (1968) Constitution and biosynthesis of capsaicin. J Chem Soc C 4:442–446

- ^ a b c d Leete E, Louden MC (November 1968). "Biosynthesis of capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin in Capsicum frutescens". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 90 (24): 6837–6841. Bibcode:1968JAChS..90.6837L. doi:10.1021/ja01026a049. PMID 5687710.

- ^ Fujiwake H, Suzuki T, Iwai K (November 1982). "Intracellular distributions of enzymes and intermediates involved in biosynthesis of capsaicin and its analogues in Capsicum fruits". Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 46 (11): 2685–2689. doi:10.1080/00021369.1982.10865495.

- ^ Fujiwake H, Suzuki T, Iwai K (October 1982). "Capsaicinoid formation in the protoplast from the placenta of Capsicum fruits". Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 46 (10): 2591–2592. doi:10.1080/00021369.1982.10865477.

- ^ Sukrasno N, Yeoman MM (1993). "Phenylpropanoid metabolism during growth and development of Capsicum frutescens fruits". Phytochemistry. 32 (4): 839–844. Bibcode:1993PChem..32..839S. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(93)85217-f.

- ^ Suzuki T, Kawada T, Iwai K (1981). "Formation and metabolism of pungent principle of Capsicum fruits. 9. Biosynthesis of acyl moieties of capsaicin and its analogs from valine and leucine in Capsicum fruits". Plant & Cell Physiology. 22: 23–32. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a076142.

- ^ Curry J, Aluru M, Mendoza M, Nevarez J, Melendrez M, O'Connell MA (1999). "Transcripts for possible capsaicinoid biosynthetic genes are differentially accumulated in pungent and non-pungent Capsicum spp". Plant Sci. 148 (1): 47–57. Bibcode:1999PlnSc.148...47C. doi:10.1016/s0168-9452(99)00118-1. S2CID 86735106.

- ^ Nelson EK, Dawson LE (1923). "Constitution of capsaicin, the pungent principle of Capsicum. III". J Am Chem Soc. 45 (9): 2179–2181. Bibcode:1923JAChS..45.2179N. doi:10.1021/ja01662a023.

- ^ Stewart C, Kang BC, Liu K, Mazourek M, Moore SL, Yoo EY, et al. (June 2005). "The Pun1 gene for pungency in pepper encodes a putative acyltransferase". The Plant Journal. 42 (5): 675–688. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02410.x. PMID 15918882.

- ^ a b c Bennett DJ, Kirby GW (1968). "Constitution and biosynthesis of capsaicin". J. Chem. Soc. C. 1968: 442–446. doi:10.1039/j39680000442.

- ^ Fujiwake H, Suzuki T, Oka S, Iwai K (1980). "Enzymatic formation of capsaicinoid from vanillylamine and iso-type fatty acids by cell-free extracts of Capsicum annuum var. annuum cv. Karayatsubusa". Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 44 (12): 2907–2912. doi:10.1271/bbb1961.44.2907.

- ^ Guzman I, Bosland PW, O'Connell MA (2011). "Chapter 8: Heat, Color, and Flavor Compounds in Capsicum Fruit". In Gang DR (ed.). Recent Advances in Phytochemistry 41: The Biological Activity of Phytochemicals. New York, New York: Springer. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-1-4419-7299-6.

- ^ Kozukue N, Han JS, Kozukue E, Lee SJ, Kim JA, Lee KR, et al. (November 2005). "Analysis of eight capsaicinoids in peppers and pepper-containing foods by high-performance liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (23): 9172–9181. doi:10.1021/jf050469j. PMID 16277419.

- ^ Thiele R, Mueller-Seitz E, Petz M (June 2008). "Chili pepper fruits: presumed precursors of fatty acids characteristic for capsaicinoids". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 56 (11): 4219–4224. Bibcode:2008JAFC...56.4219T. doi:10.1021/jf073420h. PMID 18489121.

- ^ Yang HJ, Chung KR, Kwon DY (1 September 2017). "DNA sequence analysis tells the truth of the origin, propagation, and evolution of chili (red pepper)". Journal of Ethnic Foods. 4 (3): 154–162. doi:10.1016/j.jef.2017.08.010. ISSN 2352-6181. S2CID 164335348.

- ^ Tewksbury JJ, Reagan KM, Machnicki NJ, Carlo TA, Haak DC, Peñaloza AL, et al. (August 2008). "Evolutionary ecology of pungency in wild chilies". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (33): 11808–11811. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10511808T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0802691105. PMC 2575311. PMID 18695236.

- ^ Behbehani JM, Irshad M, Shreaz S, Karched M (January 2023). "Anticandidal Activity of Capsaicin and Its Effect on Ergosterol Biosynthesis and Membrane Integrity of Candida albicans". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 24 (2): 1046. doi:10.3390/ijms24021046. PMC 9860720. PMID 36674560.

- ^ Costa-Orlandi CB, Sardi JC, Pitangui NS, de Oliveira HC, Scorzoni L, Galeane MC, et al. (May 2017). "Fungal Biofilms and Polymicrobial Diseases". Journal of Fungi. 3 (2): 22. doi:10.3390/jof3020022. PMC 5715925. PMID 29371540.

- ^ "How fungi are constructed". website.nbm-mnb.ca. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ Yang F, Zheng J (March 2017). "Understand spiciness: mechanism of TRPV1 channel activation by capsaicin". Protein & Cell. 8 (3): 169–177. doi:10.1007/s13238-016-0353-7. PMC 5326624. PMID 28044278.

- ^ Jordá T, Puig S (July 2020). "Regulation of Ergosterol Biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Genes. 11 (7): 795. doi:10.3390/genes11070795. PMC 7397035. PMID 32679672.

- ^ Li Y, Bai P, Wei L, Kang R, Chen L, Zhang M, et al. (June 2020). "Capsaicin Functions as Drosophila Ovipositional Repellent and Causes Intestinal Dysplasia". Scientific Reports. 10 (1) 9963. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.9963L. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-66900-2. PMC 7305228. PMID 32561812.

- ^ "Capsaicin Technical Fact Sheet". npic.orst.edu. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ Claros Cuadrado JL, Pinillos EO, Tito R, Mirones CS, Gamarra Mendoza NN (May 2019). "Insecticidal Properties of Capsaicinoids and Glucosinolates Extracted from Capsicum chinense and Tropaeolum tuberosum". Insects. 10 (5): 132. doi:10.3390/insects10050132. PMC 6572632. PMID 31064092.

- ^ Levey DJ, Tewksbury JJ, Cipollini ML, Carlo TA (November 2006). "A field test of the directed deterrence hypothesis in two species of wild chili". Oecologia. 150 (1): 61–68. Bibcode:2006Oecol.150...61L. doi:10.1007/s00442-006-0496-y. PMID 16896774. S2CID 10892233.

- ^ Haak DC, McGinnis LA, Levey DJ, Tewksbury JJ (May 2012). "Why are not all chilies hot? A trade-off limits pungency". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 279 (1735): 2012–2017. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.2091. PMC 3311884. PMID 22189403.

- ^ Ruiz-Lau N, Medina-Lara F, Minero-García Y, Zamudio-Moreno E, Guzmán-Antonio A, Echevarría-Machado I, et al. (1 March 2011). "Water Deficit Affects the Accumulation of Capsaicinoids in Fruits of Capsicum chinense Jacq". HortScience. 46 (3): 487–492. doi:10.21273/HORTSCI.46.3.487. ISSN 0018-5345. S2CID 86280396.

- ^ Mahmood T, Rana RM, Ahmar S, Saeed S, Gulzar A, Khan MA, et al. (June 2021). "Effect of Drought Stress on Capsaicin and Antioxidant Contents in Pepper Genotypes at Reproductive Stage". Plants. 10 (7): 1286. Bibcode:2021Plnts..10.1286M. doi:10.3390/plants10071286. PMC 8309139. PMID 34202853.

Notes

[edit]- ^ History of early research on capsaicin:

- Felter HW, Lloyd JU (1898). King's American Dispensatory. Vol. 1. Cincinnati, Ohio: Ohio Valley Co. p. 435.

- Du Mez AG (1917). A century of the United States pharmocopoeia 1820–1920. I. The galenical oleoresins (PhD). University of Wisconsin. pp. 111–132.

- The results of Bucholz's and Braconnot's analyses of Capsicum annuum appear in: Pereira J (1854). The Elements of Materia Medica and Therapeutics. Vol. 2 (3rd US ed.). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Blanchard and Lea. p. 506.

- Biographical information about Christian Friedrich Bucholz is available in: Rose HJ (1857). Rose HJ, Wright T (eds.). A New General Biographical Dictionary. Vol. 5. London, England: T. Fellowes. p. 186.

- Biographical information about C. F. Bucholz is also available (in German) online at: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie.

- Some other early investigators who also extracted the active component of peppers:

- Maurach B (1816). "Pharmaceutisch-chemische Untersuchung des spanischen Pfeffers" [Pharmaceutical-chemical investigation of Spanish peppers]. Berlinisches Jahrbuch für die Pharmacie (in German). 17: 63–73. Abstracts of Maurach's paper appear in: (i) Repertorium für die Pharmacie, vol. 6, page 117-119 (1819); (ii) Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, vol. 4, no. 18, page 146 (February 1821); (iii) "Spanischer oder indischer Pfeffer", System der Materia medica ..., vol. 6, pages 381–386 (1821) (this reference also contains an abstract of Bucholz's analysis of peppers).

- Henri Braconnot, French chemist Braconnot H (1817). "Examen chemique du Piment, de son principe âcre, et de celui des plantes de la famille des renonculacées" [Chemical investigation of the chili pepper, of its pungent principle [constituent, component], and of that of plants of the family Ranunculus]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique (in French). 6: 122- 131.

- Johann Georg Forchhammer, Danish geologist Oersted HC (1820). "Sur la découverte de deux nouveaux alcalis végétaux" [On the discovery of two new plant alkalis]. Journal de physique, de chemie, d'histoire naturelle et des arts [Journal of Physics, Chemistry, Natural History and the Arts] (in French). 90: 173–174.

- Ernst Witting, German apothecary Witting E (1822). "Considerations sur les bases vegetales en general, sous le point de vue pharmaceutique et descriptif de deux substances, la capsicine et la nicotianine" [Thoughts on the plant bases in general from a pharmaceutical viewpoint, and description of two substances, capsicin and nicotine]. Beiträge für die Pharmaceutische und Analytische Chemie [Contributions to Pharmaceutical and Analytical Chemistry] (in French). 3: 43. He called it "capsicin", after the genus Capsicum from which it was extracted. John Clough Thresh (1850–1932), who had isolated capsaicin in almost pure form,[50][51] gave it the name "capsaicin" in 1876.[52] Karl Micko isolated capsaicin in its pure form in 1898.[53][54] Capsaicin's chemical composition was first determined in 1919 by E. K. Nelson, who also partially elucidated capsaicin's chemical structure.[55] Capsaicin was first synthesized in 1930 by Ernst Spath and Stephen F. Darling.[56] In 1961, similar substances were isolated from chili peppers by the Japanese chemists S. Kosuge and Y. Inagaki, who named them capsaicinoids.[57][58]

Further reading

[edit]- Abdel-Salam OM (2014). Capsaicin as a Therapeutic Molecule. Springer. ISBN 978-3-0348-0827-9.