Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

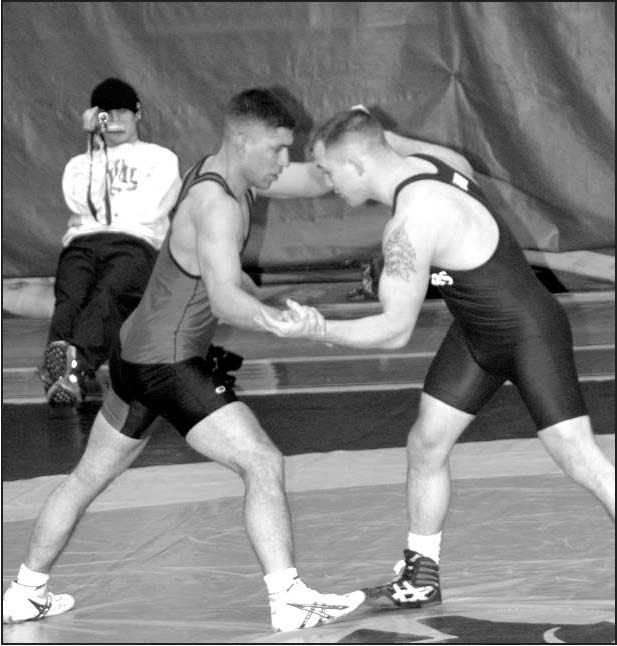

Grappling hold

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

A grappling hold, commonly referred to simply as a hold that in Japanese is referred to as katame-waza (固め技 "grappling technique"), is any specific grappling, wrestling, judo, or other martial art grip that is applied to an opponent. Grappling holds are used principally to control the opponent and to advance in points or positioning. The holds may be categorized by their function, such as clinching, pinning, or submission, while others can be classified by their anatomical effect: chokehold, headlock, joint-lock, or compression lock. Multiple categories may be appropriate for some of these holds.

Key Information

Clinch hold

[edit]A clinch hold (also known as a clinching hold) is a grappling hold that is used in clinch fighting with the purpose of controlling the opponent. In wrestling it is referred to as the tie-up. The use of a clinch hold results in the clinch. Clinch holds can be used to close in on the opponent, as a precursor to a takedown or throw, or to prevent the opponent from moving away or striking effectively. Typical clinch holds include:

Pinning hold

[edit]

A pinning hold (also known as a hold down and in Japanese as osaekomi-waza, 抑え込み技, "pinning technique") is a general grappling hold used in ground fighting that is aimed to subdue by exerting superior control over an opponent and pinning the opponent to the ground. Pinning holds where both of the opponent's shoulders touch the ground are considered winning conditions in several combat sports.

An effective pinning hold is a winning condition in many styles of wrestling, and is known as simply a "pin". Pinning holds maintained for 20 seconds are also a winning condition in judo. Pinning holds are also used in submission wrestling and mixed martial arts, even though the pinning hold itself is not a winning condition. The holds can be used to rest while the opponent tries to escape, to control the opponent while striking, a tactic known as ground and pound, or to control an opponent from striking by pinning them to the ground, also known as lay and pray.

Submission hold

[edit]

In combat sports a submission hold (colloquially referred to as a "submission") is a grappling hold that is applied with the purpose of forcing an opponent to submit out of either extreme pain or fear of injury. Submission holds are used primarily in ground fighting and can be separated into constrictions (chokeholds, compression locks, suffocation locks) and manipulations (joint locks, leverages, pain compliance holds). When incorrectly used, these techniques may cause dislocation, torn ligaments, bone fractures, unconsciousness, or even death.

Common combat sports featuring submission holds are:

List of grappling holds

[edit]The same hold may be called by different names in different arts or countries. Some of the more common names for grappling holds in contemporary English include:

Joint locks

[edit]Joint lock: Any stabilization of one or more joints at their normal extreme range of motion

- Boston Crab: A type of spinal lock originating from catch wrestling and mostly employed in professional wrestling performances, but has been used to win a fight in MMA.[1]

- Can opener: A type of neck crank

- Crucifix: A type of neck crank

- Neck crank: Applies pressure to the neck by pulling or twisting the head

- Nelson: (quarter, half, three-quarter and full): The arm is circled under the opponent's arm, and secured at the neck

- Small joint manipulation: Joint locks on the fingers or toes

- Spine crank: Applies pressure to the spine by twisting or bending the body

- Twister: A type of body bend and neck crank

- Wristlock: A general term for joint locks on the wrist or radioulnar joint; wristlocks form the trademark offense of Aikido, and are used in combination with keylocks in catch wrestling

Armlocks

[edit]Armlock: A general term for joint locks at the elbow or shoulder

- Americana: BJJ term for a lateral keylock

- Armbar: An armlock that hyperextends the elbow

- Chicken wing: Term for various hammer/keylocks, especially among Shoot wrestling and Jeet Kune Do practitioners

- Flying armbar: A type of armbar that is performed from a stand-up position

- Hammerlock: Pins the opponent's arm behind the back, with wrist toward their own shoulder

- Juji-Gatame: A type of armbar where the arm is held in-between the legs

- Keylock: A shoulderlock where the arm is turned like a key

- Kimura: BJJ term for a medial keylock

- Omoplata: BJJ term for a shoulder lock using the legs

Leglock

[edit]Leglock: A general term for joint locks at the hip, knee, or ankle

- Ankle lock: A leglock that hyper extends the ankle

- Heel hook: A leglock that attacks the knee

- Kneebar: A leglock that hyperextends the knee

- Toe hold: A type of leglock that hyper extends the ankle

Chokeholds and strangles

[edit]- Anaconda choke: A type of arm triangle choke

- Arm triangle choke: A chokehold similar to the triangle choke except using the arms

- Crosschoke: Athlete crosses own arms in "X" shape and holds onto opponent's gi or clothing

- Ezequiel: Reverse of the rear naked choke, using the inside of the sleeves for grip

- Gearlock: A modified sleeper hold that puts an incredible amount of force on the opponent's windpipe, choking them out almost instantly if applied properly [citation needed]

- Gi Choke: or Okuri eri jime as it is known in Judo is a single lapel strangle

- Gogoplata (Hell's Gate): Performed by putting one's shin on the wind pipe of an opponent and pulling the head down; typically set up from the rubber guard

- Guillotine choke: A facing choke, usually applied to an opponent from above

- Locoplata: A variation of the Gogo-plata that uses the other foot to push the shin into the windpipe and uses the arm to wrap around the back of the head to grab the foot to secure the choke

- North–south choke: A chokehold applied from the north-south position with opponent facing up; uses the shoulder and biceps to cut off air flow

- Rear naked choke: A chokehold from the rear

- Triangle choke: A chokehold that forms a triangle around the opponent's head using the legs

Clinch holds

[edit]- Bear hug: A clinching hold encircling the opponent's torso with both arms, pulling toward oneself

- Collar tie: Facing the opponent with one or both hands on the back of their head/neck

- Muay Thai clinch: Holding the opponent with both arms around the neck while standing

- Overhook: Holding over the opponent's arm while standing

- Pinch grip tie: Term for a particular harness hold, common in Greco-Roman wrestling circles

- Underhook: Holding under the opponent's arm while standing

- Tie: A transitional hold used to stabilize the opponent in preparation for striking or throwing

Compression locks

[edit]- Achilles lock: A compression lock on the achilles tendon

- Biceps slicer: A compression lock on the elbow joint and biceps

- Figure four: (also referred to as arm triangle, leg triangle) Term for arranging one's own arm or legs to resemble shape of numeral "4" when holding opponent

- Leg slicer: A compression lock on the calf and thigh

Pain compliance

[edit]- Chin lock: An arm hold on the chin that hurts the chin.

Pinning hold

[edit]- Cradle: Compress opponent in a sit-up position to pin shoulders from side mount

- Staple: Using the opponent's clothing to help pin them against a surface

Other grappling holds

[edit]- Banana Split: A flexibility-based grappling submission

- Grapevine: Twisting limbs around limbs in a manner similar to a plant vine

- Harness: A hold that encircles the torso of an opponent, sometimes diagonally

- Headlock: Circling the opponent's head with an arm, especially from the side; also called a rear Chancery

- Hooks: Wrapping the arm or leg around an opponent's limb(s) for greater control

- Leg scissors: Causes compressive asphyxia by pressing the chest or abdomen

- Scissor: Places the opponent between the athlete's legs (like paper to be cut by scissors)

- Stack: Compresses the opponent in a vertical sit-up position (feet up) to pin their shoulders to mat

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "VIDEO - This Fighter Just Pulled Off a Boston Crab Submission in MMA - BJPenn.com". bjpenn.com. 30 September 2017.

- Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu: Theory and Technique by Renzo Gracie and Royler Gracie (2001). ISBN 1-931229-08-2

- Championship Wrestling, Revised Edition. (Annapolis MD: United States Naval Institute, 1950).

- No Holds Barred Fighting: The Ultimate Guide to Submission Wrestling by Mark Hatmaker with Doug Werner. ISBN 1-884654-17-7

- Small-Circle Jujitsu by Wally Jay. (Burbank CA: Ohara Publications, 1989).

External links

[edit]- Free Jiu-Jitsu and Submission Grappling Videos Archived 2007-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- The Subtle Science of the Muay Thai Clinch By Roberto Pedreira Includes pictures of common Muay Thai clinching holds.

- Lessons in Wrestling and Physical Culture, a scan of the 1912 correspondence course from Martin 'Farmer' Burns.

- List of Submissions for MMA Grappling holds and submissions used in MMA. Each submission links to videos and step by step instruction.

- categorized judo techniques on video - Tournaments, champions, Olympics etc.

- Mixed Martial Arts Search Engine A search engine covering all things exclusive to MMA.

- MMA Training Free MMA Training help and advice.

- MMM Submission Moves Archived 2018-03-08 at the Wayback Machine 10 Submission Moves For MMA Athletes.

- Female Wrestling Channel Rules Competitive Female Wrestling Pin and Submission Rules at the Female Wrestling Channel

- [1] Free book focusing on the mount position