Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

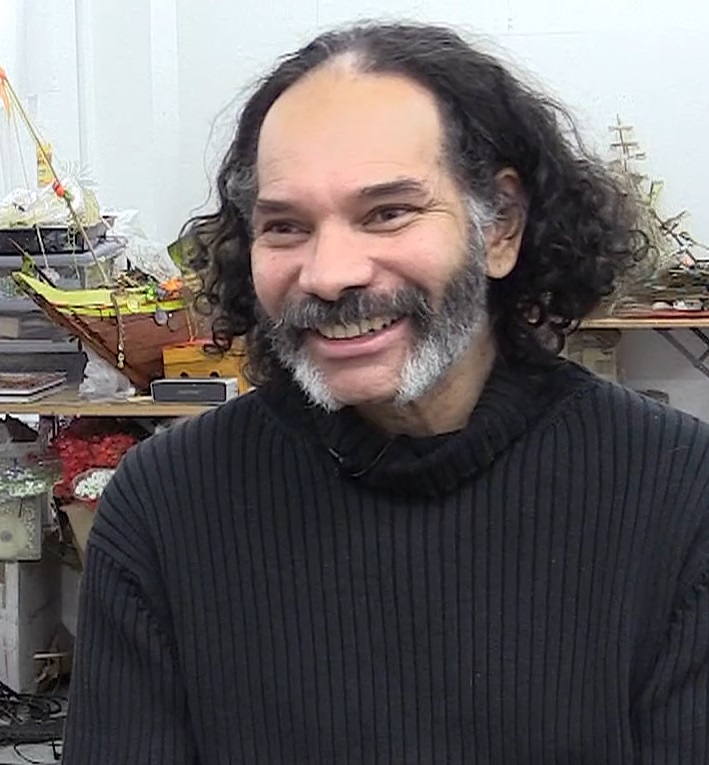

Hew Locke

View on WikipediaHew Donald Joseph Locke OBE RA (born 13 October 1959) is a British sculptor and contemporary visual artist based in Brixton, London. In 2000, he won a Paul Hamlyn Award[1] and the EASTinternational Award.[2] He grew up in Guyana, but has lived most of his adult life in London.[3]

Key Information

In 2010, he was shortlisted for the Fourth plinth, Trafalgar Square, London.[4] In 2015, Prince William, Duke of Cambridge dedicated Locke's public sculpture The Jurors, commissioned to commemorate 800 years since the signing of Magna Carta.[5]. In 2025 his permanent series of sculptures "Cargoes" was installed at King Edward Memorial Park, London, consisting of 6 bronze boats illustrating the history of the Thames and the local community.

Locke has had several solo exhibitions in the UK and USA, and is regularly included in international exhibitions and Biennales.[6] His works have been acquired by collections such as Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM), Florida, The Tate gallery, London[7] and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[8] In 2016, the National Portrait Gallery in London acquired a portrait of Locke by Nicholas Sinclair.[9] In 2022, he became a member of The Royal Academy of Arts.[10]

He was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 2023 Birthday Honours for services to art.[11][12] In 2024, he was awarded an Honorary Doctorate by Edinburgh University.[13]

Background

[edit]Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1959, Locke is the eldest son of Guyanese sculptor Donald Locke (1930–2010)[14] and British painter Leila Locke (née Chaplin) (1936–1992).[15] He spent his formative years (1966 to 1980) in Georgetown, Guyana, before returning to the UK to study.[16] He received a B.A. Fine Art degree in 1988 from Falmouth University, and an M.A. in Sculpture from the Royal College of Art, London, in 1994. In 1995 he married curator Indra Khanna.[17]

Work and themes

[edit]Prof. Dr. Ingrid von Rosenberg has written: "(Black) Artists who continue to produce work with a critical message, like Yinka Shonibare and Hew Locke, avoid the open confrontation typical of the 1980s and instead use humour and satire, positioning themselves as cultural insiders, rather than excluded outsiders."[18]

He has cited architecture ranging from the Baroque, Rajput, Islamic, and Caribbean vernacular to Victorian funfairs as influences.[19][20] Locke uses a wide range of media, makes extensive use of found objects, and his recurrent themes include cardboard, royalty, public statues, boats, finance and trade.[17]

Cardboard

[edit]Locke has said about misreadings of his work in his early career: "I would make a sculpture and people would think it was made for some festival....It was seen as being from a folk tradition, not as being of its own tradition, true to itself – as art basically...I stopped making work in colour for three years, I just dropped it."[21]

Curator Kris Kuramitsu wrote: "Frustrated by the fact that his biography so heavily over-determines the reading of his work, he created a series of sculptures in which he used cardboard to preemptively package the work for the viewer. This move was revelatory for Locke's practice, as through this material he could metonymically address migration, international economics, globalisation and ideas about personal and cultural protection and projection."[22]

Royalty

[edit]His ongoing series House of Windsor consists of portraits of members of the British royal family.

He has said: "People ask me why I'm working on pictures of the royal family....They expect me to be angry, but I don't see the point. If you're going to fight in Iraq, then you're going to fight for Queen and Country. When you hand in your passport, you see that you are in fact a subject of the Queen. My work is a weird kind of acceptance of that situation."[23]

"My feelings about the Royal Family are ambivalent. I am simply fascinated by the institution and its relationship to the press and public. My political position is neither republican nor monarchist."[18]

Statues

[edit]In an interview with Simon Grant, Locke said: "...the legacy of empire is all around us on a daily basis – not just the variety of ethnic backgrounds that we have living in the UK, but the buildings and public statues that you see in cities across the country that came into being out of the economy of empire."[24]

Locke often works over photographs of specific statues, covering areas with painted or collaged designs.[25] The press release for his work Restoration describes "Hew Locke’s embellishment, directly on to the photographic print, interrupts our expectation that the surface of the photographic image should be left pristine. We can only guess at what lies beneath ...It is perhaps the image of Colston that is most haunting. He is adorned with cowrie shells and other trade beads ... we are made aware of his ... involvement in the uncomfortable truths of corrupt African Kingdoms selling their people ... Locke views this work as an act of 'mindful vandalism', an exploration of these characters who he finds both attractive and repellent."[26]

Locke said: "When travelling around Britain, the first things I'm looking for are the statues ... I often think 'why have they got a statue to this person and why to that person?' ... On a purely aesthetic level I often find these historical monuments beautiful and have a genuine respect for their skilled academic sculptors. I have a somewhat schizophrenic response. It is not an anti-military critique, but an investigation into the idea of the Hero, and a meditation on our relationship with monumental public sculpture."[27]

Boats

[edit]Ships have been a constant theme in his work throughout his career, ranging from small paintings to installations filling a church nave or an installation across an entire battle ship.[28] A major example of Locke's interest in navigational vessels in visual arts is his 2011 installation For Those in Peril on the Sea, acquired by the Pérez Art Museum Miami.[29]

He has said: "I have a deep personal compulsion to make at least one boat every two years or so. It is part of my personal history, having sailed to and from Guyana to England as a child."[30]

Curator Zoe Lukov has written: "Locke offers us a maritime procession – at once celebratory and funereal – that is animated by the sub-marine pulse of history...a synthesis of symbols from intertwined historical and cultural legends and narratives...disparate legacies that surf the waves."[31]

Locke described his 2019 mixed-media installation Armada, made up of 45 boat sculptures,[32][33] as addressing the reality that "today's refugee is tomorrow's citizen".[34]

Finance and trade

[edit]

Curator Amanda Sanfilippo of Fringe Projects, Miami, wrote that Locke "utilizes share certificates ... to embody the history and global movement of money, power and ownership. Since the financial crash of 2008, Hew Locke has been acquiring original antique share certificates and applying paint to their surfaces. Locke ... often highlights historical and economic cycles, the machinations of global currency and exchange. ... Figures representative of the local population in the areas in which the companies operated are sometimes seen breaking-through. These are silent witnesses, those who paid the most to create the wealth without receiving the benefit...This work... is also a wry acknowledgement of the commodity value of contemporary art."[35]

Art Daily reported that his 2017 work Cui Bono "refers to the wealth that maritime trade brought to Bremen’s merchants. The search for wealth, violent conquest and a desire for safety are factors that for centuries have driven the global movement of people...(it) is a post-colonial incentive to grapple with Bremen's maritime commercial and colonial history."[36]

Selected solo exhibitions and presentations

[edit]- 2000: Hemmed In Two, The Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- 2002: The Cardboard Palace, Chisenhale Gallery, London

- 2004: House of Cards, Luckman Gallery, California State Uni & Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, USA

- 2004: King Creole, installation on facade of Tate Britain & at BBC New Media Village, London

- 2005: Hew Locke, The New Art Gallery, Walsall

- 2006: Restoration, St Thomas the Martyr's Church, Bristol

- 2008: The Kingdom of the Blind, Rivington Place, London

- 2011: For Those in Peril on the Sea, St. Mary & St. Eanswythe church, Folkestone Triennial

- 2015: The Tourists, HMS Belfast, London

- 2018: Hew Locke: For Those in Peril on the Sea, Pérez Art Museum Miami, Florida[37]

- 2019: Hew Locke; Here's the Thing, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City & Colby College Museum of Art in Maine

- 2022: The Procession, Duveen Hall Commission, Tate Britain, London

- 2022: Foreign Exchange, temporary public sculpture co-inciding with The Commonwealth Games, Birmingham, UK

- 2022: Gilt, Facade Commission at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- 2024: Hew Locke: The Procession, ICA Watershed at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA[38][39]

- 2024: Hew Locke: What have we here?, British Museum, London[40]

- 2025: Hew Locke: Passages, Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus OH & The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston

Monographs

[edit]- Hew Locke, Walsall, UK: The New Art Gallery Walsall, 2005, ISBN 0-946652-77-5

- How Do You Want Me?, Paris, France: Editions Janninck, 2009, ISBN 978-2-916067-41-4

- Stranger in Paradise, London, UK: Black Dog, 2011, ISBN 978-1-907317-38-5

- Here's the Thing, Birmingham, UK: Ikon Gallery, Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art & Colby College Museum of Art, 2019, ISBN 978-1911155218

- Hew Locke: What have we here?, London, UK: The British Museum Press, 2024, ISBN 978-0-714123509

- Hew Locke: Passages, London, UK: Yale University Press, 2025, ISBN 9780300284683

References

[edit]- ^ Jones, Jonathan (30 September 2000). "Five Card Trick". The Guardian Weekend.

- ^ "Hew Locke", Artnet.

- ^ "Hew Locke: In Conversation With Jarrett Earnest". The Miami Rail. 5 June 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ Singh, Anita (19 August 2010). "Fourth Plinth contenders". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Davis, Eleanor (16 June 2015). "Magna Carta: Prince William unveils Hew Locke's new artwork The Jurors at Runnymede". Get Surrey. Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ Hew Locke website/CV. Retrieved 2018.

- ^ "The Tate collection online". Retrieved 2018.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection online". Retrieved 2018.

- ^ "The National Portrait Gallery online". Retrieved 2018.

- ^ "royalacademy.org". Retrieved 2022.

- ^ "No. 64082". The London Gazette (Supplement). 17 June 2023. p. B13.

- ^ "Gov.uk". Retrieved 2023.

- ^ "ed.ac.uk". Retrieved 2025.

- ^ "Sculptor Donald Locke passes away", Stabroek News, 7 December 2011. Retrieved 2011.

- ^ Earl, Claudette, "Leila Elizabeth Locke – an appreciation", Chronicle Family Magazine, 19 April 1992.

- ^ Duff, L., & P. Sawdon, Drawing – the Purpose, Intellect Ltd, 2008.

- ^ a b Locke's website. Retrieved 2018.

- ^ a b Von Rosenberg, Ingrid, "Transformations of Western Icons in Black British Art", Journal for the Study of British Culture, Vol. 15/1, 2008.

- ^ Duffy, Ellie, review of "Cardboard Palace", Building Design magazine, issue 1529, 29 February 2002.

- ^ Jonathan Jones, review of "Cardboard Palace", Contemporary magazine, June 2002, p. 160.

- ^ Hew Locke in conversation with Richard West, Source magazine, issue 55, p. 9, Summer 2008.

- ^ Hew Locke, The New Art Gallery Walsall, 2005.

- ^ "Glitterbug", The Guardian Weekend, 31 January 2004, p. 58.

- ^ Grant, Simon, "Legacies of Empire", Tate Etc magazine, issue 35, p. 74, Autumn 2015.

- ^ Hew Locke website/statues. Retrieved 2018.

- ^ Bristol art's organisation Spike Island's press release for commissioning of Restoration as part of British Art Show 6, September 2006.

- ^ Hew Locke website/sikandar. Retrieved 2018.

- ^ Hew Locke website/boats. Retrieved 2016.

- ^ "Hew Locke | For Those in Peril on the Sea". Hales Gallery. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ "Second Lives: Remixing the Ordinary'", Museum of Arts & Design, ISBN 1-890385-14-X.

- ^ Hew Locke – The Wine Dark Sea, catalogue published by Edward Tyler Nahem Fine Art, 2016.

- ^ "Museum Moment: Hew Locke, Armada". 8 April 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Hew Locke | Armada 2017–2019". Tate. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ Campbell, Joel (15 February 2022). "Hew Locke's 'Armada' unveiled at Tate Liverpool". The Voice. Retrieved 19 February 2024.

- ^ Fringe Projects Miami website. Retrieved 2018.

- ^ "Intervention by artist Hew Locke on view in the Bremen Town Hall", Art Daily, 9 August 2017. Retrieved 2018.

- ^ Davis, Melissa Hunter (7 December 2017). "Sugarcane Raw: Hew Locke and For those in Peril on the Sea". Sugarcane Magazine™| Black Art Magazine. Retrieved 9 May 2023.

- ^ Whyte, Murray (23 May 2024). "At ICA's Watershed, Hew Locke's rough pageant of humanity". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "ICA Watershed opens 2024 season with U.S. debut of Hew Locke's monumental work The Procession". Institute of Contemporary Art / Boston. 25 March 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ Eshun, Ekow (24 October 2024). "'It's A Grand Classical Building But It's Built on Violence' Hew Locke on his skewering British Museum exhibition What Have We Here?". British Vogue. Retrieved 8 December 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Artist Interview: Hew Locke Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2014 on YouTube

- Prisoners of the Sun: A conversation with Hew Locke and Prof. Kobena Mercer on YouTube, University of Miami

- "Hew Locke – 'Let's make something positive' | Tate". Hew Locke at Tate Britain talks about his piece The Procession.

- BP Artists Talk: Hew Locke, in conversation with Marcus Verhagen at Tate Britain site

- BP Artists Talk: Hew Locke, in conversation with Gus Casley-Halford at Birmingham 2022 Festival

Hew Locke

View on GrokipediaHew Locke OBE RA (born 13 October 1959) is a British sculptor and contemporary visual artist of Guyanese descent, based in London, whose practice centers on intricate mixed-media installations and sculptures that probe colonial and post-colonial power structures, migration, and economic symbolism through appropriated everyday objects such as plastic replicas, fabrics, and ephemera.[1][2][3]

Born in Edinburgh, Locke relocated with his family to Georgetown, Guyana, in 1966, where he resided until 1980 amid the nation's post-independence era, before returning to the United Kingdom; he later pursued formal training, earning a BA in fine art from Falmouth School of Art in 1988 and an MA in sculpture from the Royal College of Art in 1994.[4][5]

Locke's oeuvre frequently features motifs of ships, regalia, and altered artifacts to dissect histories of trade, authority, and cultural exchange, with standout commissions including The Procession for Tate Britain's Duveen Galleries in 2022—a procession of over 150 figurative sculptures addressing collective memory and societal fractures—and What have we here?, a 2024 intervention at the British Museum recontextualizing collection objects through temporary assemblages.[3][6] His accolades encompass the Paul Hamlyn Award and East International Award in 2000, election as a Royal Academician in 2022, and appointment to the Order of the British Empire in 2023.[4][7]

Early Life and Background

Birth and Family Origins

Hew Locke was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1959, during a period when his father was studying there.[8][5] He is the eldest son of Donald Locke (1930–2010), a sculptor born in Guyana on the northern coast of South America, and Leila Locke (née Wenlock), a British painter.[9][10][5] The Lockes' family background reflects a blend of Guyanese and British heritage, with Donald Locke's work rooted in Caribbean artistic traditions influenced by his upbringing in Guyana, a former British colony.[10] Leila Locke, originating from Britain, contributed to the household's artistic environment through her painting practice.[5] This dual cultural lineage, centered on visual arts, shaped the early familial context in which Hew Locke grew up, prior to the family's relocation to Georgetown, Guyana, in 1966.[11][5]Childhood in Scotland and Guyana

Hew Locke was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1959 to Guyanese parents Donald Locke, a sculptor, and Leila Locke, a painter, while his father pursued studies in the United Kingdom.[5][8] The family resided in Scotland for Locke's early years until 1966, when they relocated by sea to Georgetown, Guyana, coinciding with the country's declaration of independence from British rule on May 26, 1966.[6][4] In Guyana, Locke spent his formative childhood and teenage years immersed in a culturally vibrant environment shaped by the nation's post-colonial transition and his family's artistic milieu.[5] Surrounded by his parents' creative practices, he observed and participated in an atmosphere rich with sculpture and painting, which influenced his early exposure to art amid Guyana's diverse ethnic and historical landscape.[5] The family frequently traveled by boat between Guyana and the United Kingdom during this period, fostering Locke's familiarity with maritime routes and transatlantic connections.[12] Locke resided in Georgetown from 1966 until 1980, when he returned to the United Kingdom at age 21 to pursue further education, marking the end of his primary upbringing in Guyana.[4][11] This dual experience of Scottish birth and Guyanese rearing, punctuated by independence-era changes and familial artistry, laid foundational elements for his later thematic interests in migration, empire, and cultural hybridity.[13][6]Influences from Colonial History

Locke's exposure to colonial history began in earnest upon his family's relocation from Scotland to Georgetown, Guyana, in 1966, mere months before the territory achieved independence from British rule on May 26 of that year.[6] This timing positioned him as a young observer of the immediate post-colonial transition, where symbols of imperial authority—such as statues of British monarchs and officials—remained embedded in the urban landscape amid efforts to forge a new national identity.[13] He recalls witnessing the creation of Guyana's independence flag and the broader process of a "nation being born," which instilled an early awareness of how colonial legacies persisted in everyday visibility, from architecture to public monuments.[13] A particularly vivid memory from his Guyana childhood involved frequently passing a damaged statue of Queen Victoria in Georgetown, which had been targeted during anti-colonial protests and relocated but not fully restored until after independence.[14] This encounter with defaced imperial iconography highlighted the tangible residues of British dominion, including the economic and cultural infrastructures left behind, such as remnants of plantation systems and trade networks tied to slavery and resource extraction. Guyana's history as a British colony, acquired in 1814 through the Treaty of London and shaped by the abolition of slavery in 1834 followed by indentured labor imports from India and China, formed the backdrop against which Locke absorbed these influences.[15] Such experiences contrasted sharply with his Scottish upbringing, fostering a dual perspective on empire's hierarchies and their unraveling.[16] These formative observations extended to cultural practices blending colonial imports with local adaptations, notably the Guyanese Christmas masquerades Locke attended as a child, which originated from European carnival traditions introduced by British colonizers but evolved into syncretic expressions of resistance and festivity.[17] The masqueraders' elaborate costumes, often featuring oversized headdresses and motifs evoking power and otherworldliness, echoed imperial regalia while subverting it through Caribbean improvisation—a dynamic that later informed Locke's own use of appropriation to critique colonial visual codes.[18] Residing in Guyana until 1980, he encountered a society grappling with the Burnham government's cooperative socialism amid lingering colonial economic dependencies, which deepened his sensitivity to themes of sovereignty, trade imbalances, and the psychological imprint of empire on post-independence identity.[19] This period's blend of erasure and retention of colonial artifacts—evident in museums, currency, and public spaces—cultivated Locke's enduring interest in how historical power structures manifest materially, prompting his art to interrogate rather than merely commemorate such histories.[20]Education and Early Career

Formal Training

Hew Locke pursued his undergraduate education in fine art at Falmouth School of Art (now part of Falmouth University), graduating with a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) degree in 1988.[4] [21] This followed his return to the United Kingdom from Guyana in 1980, marking the start of his structured artistic development in a British context.[11] Locke then advanced to postgraduate study at the Royal College of Art in London, where he specialized in sculpture and completed a Master of Arts degree in 1994.[4] [2] His time at the RCA built on foundational skills from Falmouth, emphasizing sculptural techniques that would inform his later use of mixed media and assemblage.[3] These programs provided Locke with technical proficiency in three-dimensional form and material manipulation, though his practice increasingly incorporated autobiographical and cultural elements drawn from personal experience rather than strictly institutional curricula.[22]Initial Artistic Experiments

Locke's initial artistic experiments following his 1994 MA in sculpture from the Royal College of Art centered on deconstructing symbols of British imperial authority through portraits of the monarchy. He produced numerous depictions of Queen Elizabeth II and other royal figures, employing layered assemblages of appropriated imagery such as coats-of-arms, trophies, weaponry, and regalia to juxtapose historical power with contemporary critique.[3] These works marked his shift toward multimedia approaches, incorporating drawings, paintings, and small-scale sculptures that reworked pre-existing objects and photographs to explore colonial legacies.[23] A key series from this period, the House of Windsor, featured drawings and paintings of royal heads, evolving into sculptural forms using materials like wood, cardboard, and colored plastics to create hybrid, ornamental busts.[23] For instance, early experiments included adorning antique busts—such as in the Souvenir series, exemplified by Souvenir 9 (Queen Victoria) (date unspecified, circa 1990s)—with eclectic elements like plastic flowers, beads, and symbolic motifs evoking empire's detritus.[9] These pieces tested Locke's technique of visual overload, layering inexpensive found objects to subvert traditional portraiture and highlight the constructed nature of authority.[24] By the late 1990s, Locke extended these experiments to freestanding sculptures like Mercenary, Raft, and Ark, which incorporated architectural influences from Guyana and Europe, blending personal heritage with themes of migration and power structures.[23] These initial efforts, often site-specific or gallery-based, laid the groundwork for his signature use of everyday materials to interrogate historical narratives, gaining recognition through early exhibitions such as Hemmed In Two at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2000.[4] The experiments demonstrated a deliberate departure from conventional sculpture toward accumulative, narrative-driven assemblages, prioritizing symbolic density over minimalism.[3]Artistic Practice and Techniques

Use of Found Materials

Hew Locke employs found objects and recycled materials as core elements of his sculptural practice, sourcing items such as plastic toys, beads, sequins, laminates, and discarded packaging to construct layered, associative works that critique global trade, empire, and consumption.[9] These materials, often vibrant and mass-produced, are selected for their postcolonial resonances, drawing from the detritus of consumer culture to symbolize the enduring legacies of colonialism and migration.[6] Locke alters and assembles these readymades through collage-like techniques, combining them with bought or collected elements to create hybrid forms that evoke both historical artifacts and contemporary excess.[25] In his boat installations, such as those featured in exhibitions like Here's the Thing at Ikon Gallery, Locke integrates found plastics and synthetic materials to fabricate vessel-like structures, representing human journeys across oceans and the commodification of movement.[26] These works, constructed from everyday ephemera like bottle tops and costume jewelry, highlight the disposability of modern goods while nodding to Guyana's maritime history and the transatlantic slave trade.[27] Similarly, in The Procession (2022) at Tate Britain, Locke assembled over 150 life-sized figures from recycled food packaging, single-use plastics, and other found scraps, forming a monumental parade that interrogates British imperial pageantry through the lens of waste and renewal.[28] Locke's approach to found materials extends to interventions on existing objects, as seen in his adornment of photographs or sculptures with suffocating arrays of beads, wires, and laminates, transforming them into ornate critiques of power symbols like statues or trophies.[29] This method, evident in series like Raw Materials (2024) at Almine Rech, emphasizes tactile accumulation, where the sheer volume of layered plastics and synthetics creates a baroque density that mirrors the opulence of empire built on exploited resources.[30] By repurposing these low-value items, Locke underscores causal links between historical extraction and present-day environmental degradation, privileging empirical observation of material flows over abstract narratives.[31]Symbolic Motifs and Construction Methods

Hew Locke's construction methods center on assemblage, where he combines and alters found objects with mixed media to create layered sculptures. He frequently incorporates everyday materials such as plastic toys, beads, sequins, and cardboard, adapting them to form complex structures that evoke historical and cultural narratives.[9][32] For instance, in works like those intervening on public statues, Locke crafts elements from cardboard, casts them in resin, and paints them gold to add masks or helmets, transforming the originals without permanent alteration.[9] This approach allows for temporary, reversible modifications that highlight underlying histories through accretions of mass-produced items.[33] Recurring symbolic motifs in Locke's oeuvre include boats, which represent the movement of goods, people, and ideas across colonial trade routes and migration paths. These vessels, often reimagined rather than faithfully modeled, integrate decorative elements like plastic figurines to symbolize cargoes of cultural exchange and exploitation.[34][35] Crowns, thrones, and royal busts recur as emblems of authority and imperial power, frequently adorned with talismans, crests, trade beads, and memento mori to critique the burdens of colonialism.[36] Heraldic symbols, coats of arms, and Masonic iconography further appear, juxtaposed with modern plastics to underscore the persistence of power structures in contemporary contexts.[37] Other motifs, such as stilt houses and share certificates, evoke fragility, economic histories, and postcolonial tensions.[38] Through these, Locke employs visual languages of authority to probe identities shaped by empire.[3]Major Themes

Empire, Colonialism, and Trade

Hew Locke's artistic practice frequently examines the mechanisms and legacies of empire and colonialism, particularly through maritime imagery symbolizing trade routes and global exchange. His boat installations, constructed from found materials like plastic flowers and beads, evoke the vessels that facilitated colonial expansion, mercantilism, and the transatlantic slave trade, linking historical exploitation to contemporary globalization.[39][40] In exhibitions such as "Hew Locke: Here's the Thing" at Colby College Museum of Art (2019), these nautical forms underscore the vectors of colonialism, post-colonialism, and diaspora, drawing on Guyana's history as a British colony reliant on sugar plantations worked by enslaved Africans. Locke integrates motifs of trade beads and military insignia to critique the economic underpinnings of imperial power, portraying empire not as abstract glory but as a system of extraction and control.[39][36] The 2024 British Museum exhibition "Hew Locke: what have we here?", co-curated by the artist and running from October 17, 2024, to February 2025, directly confronts colonial histories by reimagining museum objects under themes of trade, conflict, and treasure. Locke adorns artifacts like coins and seals with layered embellishments, questioning narratives of British imperialism and highlighting the plundered wealth accumulated through colonial commerce.[41][42] Locke's site-specific works, including "The Procession" commissioned for Tate Britain in 2022, intertwine empire with trade and global finance, featuring effigies that reference oil extraction and migratory flows tied to colonial disruptions. These pieces avoid didactic moralizing, instead using exuberant, accumulative aesthetics to reveal the intertwined causality of historical trade networks and enduring power imbalances.[43][44]Power Structures: Royalty and Statues

Locke's engagement with royalty in his art often involves reworking historical busts to interrogate symbols of monarchical authority and imperial legacy. In his Souvenirs series, begun in 2018, he appropriates Victorian-era Parian ware busts of figures such as Queen Victoria, adorning them with layered elements including crests, crowns, trade beads, memento mori skulls, tropical foliage, and military insignia to evoke the burdens of colonialism and the artifice of power.[36][41] These modifications transform the busts from straightforward commemorations into hybrid forms that blend opulence with decay, highlighting how royal imagery has historically reinforced British identity and dominance.[45] A notable example is Souvenir 10 (Princess Alexandra) (2019), a reworked bust derived from Mary Thornycroft's 19th-century marble sculpture of Princess Alexandra of Denmark, queen consort to Edward VII. Locke encases the figure in regalia that merges regal pomp with symbols of conquest, contrasting Victorian idealization of monarchy with contemporary scrutiny of its role in perpetuating power structures.[45] Similarly, Souvenir 20 (Queen Victoria) incorporates empire-related motifs like skulls and foliage, underscoring the dualities of glory and exploitation embedded in royal representation.[41] These works, displayed in exhibitions such as "Where Lies the Land?" at Hales Gallery in London from September 26 to December 7, 2019, employ everyday and found materials to subvert the busts' original porcelain purity, revealing the constructed nature of authority.[36] Locke's treatment of statues extends this critique to public monuments, which he views as enduring emblems of hierarchical power and historical narrative control. His practice includes proposals for "dressing" existing statues, as initiated in the Natives and Colonials project, aimed at temporarily altering urban memorials to expose their ties to colonial authority without permanent destruction.[46] In broader series like those featured in "Hew Locke: Passages" at the Yale Center for British Art (opened October 17, 2024), he reimagines public statuary through appropriation, drawing on portraiture and architectural motifs to challenge the visual codes of empire and sovereignty.[6] These interventions question the sanctity of statues depicting royalty or imperial figures, positioning them as sites of contested memory rather than fixed truths.[9] Through these motifs, Locke employs a "postcolonial baroque" style—characterized by excess, fragmentation, and recombination—to dissect how royalty and statues encode power dynamics, from monarchical continuity to the commodification of history.[6] His works avoid simplistic condemnation, instead layering empirical references to trade, warfare, and migration to foster reflection on causal links between past symbols and present global inequalities.[3]Migration and Human Journeys

Hew Locke's engagement with migration and human journeys draws from his personal history of transatlantic relocation, having been born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1959 and moved by boat to Georgetown, Guyana, in 1966, where he resided until returning to the United Kingdom in 1980.[6][5] This experience informs his recurrent use of boats as metaphors for life's precarious voyages, displacement, and the quest for refuge, reflecting broader diasporic narratives and the maritime pathways of colonial and post-colonial movements.[9] In installations like Armada, comprising 45 intricately detailed model boats suspended as a fleet, Locke symbolizes global migration, trade, and colonial legacies, with vessels laden with plastic toys, costume jewelry, shells, and coins to evoke the personal belongings carried by migrants seeking new lives.[9] These works portray boats not merely as transport but as containers of human aspiration and vulnerability, as Locke has stated: "Some are containers for people who are trying to get to a new life."[9] The 2016 exhibition The Wine Dark Sea featured 25 hanging sculptural vessels, ranging from container ships and battleships to small rowboats, which address themes of migration, displacement, and cultural notions of home amid humankind's fraught relationship with the sea.[47] A modest wooden rowboat in the series, for instance, evokes timeless yet contemporary refugee crossings, underscoring the enduring perils of unauthorized sea journeys.[47] Locke's 2019 exhibition Here's the Thing at the Colby College Museum of Art presented suspended nautical sculptures that trace the vectors of mercantilism, colonialism, post-colonialism, migration, and diaspora, reconfiguring symbols of nationhood and power to highlight the human dimensions of oceanic traversal and cultural exchange.[39] Through these motifs, Locke maintains an attunement to the lived realities of migrant and diasporic communities, navigating between Guyana and London in his own practice.[11]Finance and Global Exchange

Locke's artistic engagement with finance and global exchange frequently draws on historical artifacts of economic systems, such as share certificates and trade symbols, to interrogate their ties to colonial exploitation and power dynamics. These works reveal the decorative facades of financial instruments, which often obscure narratives of wealth accumulation through empire and maritime commerce. By repurposing found ephemera like obsolete stock documents, Locke underscores the precariousness of economic fortunes and the global circuits of capital that fueled historical inequalities.[48][43] A prominent example is Gold Standard (2012), a site-specific installation commissioned for the Deptford X festival in London, where Locke affixed large-scale printed reproductions of 19th-century share certificates across two commercial buildings on Frankham Street, spanning 19 meters. The ornate, gilded designs of these documents—evoking the gold standard era of currency—contrasted with the derelict urban setting, critiquing the speculative bubbles and imperial trade underpinnings of early capitalism; Locke noted their "highly decorative" quality hid "not so beautiful" stories of economic exploitation. Materials included wheat-pasted posters on building facades, transforming public space into a reflection on finance's historical allure and volatility.[49][50] In Reversal of Fortune (2017), installed in a vacant Art Deco jewelry store within Miami's Alfred I. duPont Building as part of Fringe Projects, Locke selected and enlarged 15 historical financial certificates for display on the facade and interior vault. This intervention evoked cycles of boom and bust, with the empty storefront symbolizing economic decline amid glittering promises of wealth; the work linked personal fortunes to broader global exchanges, including those tied to colonial resource extraction. Fiberglass, resin, and printed media were employed to mimic the store's commercial past, prompting viewers to consider reversals in economic power structures.[51][52] Sea Power (2014), created for the Kochi-Muziris Biennale in an abandoned trading company warehouse on Cochin's harbor, incorporated sculptural elements inspired by maritime history, including references to Vasco da Gama's ships and Roman statuary, to explore naval dominance as a mechanism of global trade routes. Plastic toys, beads, and fabricated ship models formed hybrid figures, symbolizing the fusion of military might and economic expansion that defined colonial exchange networks. The installation highlighted how sea power facilitated the flow of goods, currencies, and influence across empires.[53][54] These pieces, alongside motifs in larger series like The Procession (2022), integrate financial symbolism—such as currency flows and commodity trades—into critiques of globalization, where economic systems perpetuate hierarchies rooted in historical conquests rather than neutral market forces. Locke's use of accessible, mass-produced materials democratizes these examinations, revealing causal links between finance, empire, and ongoing disparities without endorsing ideological narratives from secondary interpretations.[55][43]Key Works and Series

Early Cardboard Sculptures

Hew Locke's initial forays into cardboard as a primary material occurred during his MA exhibition at the Royal College of Art in 1994, where he presented a large-scale boat constructed from cardboard and papier-mâché, marking an early exploration of ephemeral, assembled forms that evoked themes of migration and cultural transport.[56] This work laid groundwork for his subsequent use of cardboard's disposability to critique commodification and fragility in cultural artifacts.[56] In 2000, Locke produced two significant cardboard-based installations that expanded this approach. Hemmed in Two, exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum, comprised a sprawling, precarious structure approximately 15 by 22 feet, fashioned from cardboard, wood, acrylic, glue, and felt-tip pen, blending boat-like forms with packaging motifs to reflect on the global commodification of culture and historical entanglements of trade and empire.[57] [19] [55] Simultaneously, he received his first major public commission: a giant cardboard ship suspended over the atrium of the Team Valley Shopping Centre in Gateshead, underscoring cardboard's capacity for temporary, site-responsive spectacle while probing consumerist and maritime narratives.[58] These efforts culminated in Cardboard Palace (2002), commissioned for Chisenhale Gallery from 24 April to 2 June, a maze-like architectural ensemble measuring 4 by 11.1 by 19.7 meters, built primarily from cardboard clad with intricate drawings referencing temples, mosques, Caribbean vernacular, and Rajput styles, interspersed with oversized royal portraits and commodity texts.[59] [60] Created amid Queen Elizabeth II's Golden Jubilee, the installation interrogated British heritage's ambiguities, using cardboard's tension between shell and content to symbolize cultural packaging and unpacking.[59] [60] This series established cardboard as a signature medium in Locke's early practice, enabling layered critiques of power, history, and materiality through accessible, mutable forms.[61]Boat Installations

Hew Locke's boat installations consist of suspended sculptures crafted from modified plastic toy boats, found objects, and custom-built elements, often embellished with beads, shells, and political insignia to symbolize voyages of migration, trade, and colonial exchange. These works, typically arranged as flotillas hanging at shoulder height, immerse viewers in a dense array of vessels representing diverse historical and cultural contexts, from ancient warships to modern migrant crafts.[62][63] A pivotal series, "For Those in Peril on the Sea," features customized models of boats from various global traditions alongside purpose-built vessels, each serving as a memorial to maritime disasters and human journeys, with no visible crew to emphasize absence and loss. The installation draws on the hymn title to evoke vulnerability at sea, incorporating elements like flags and talismans for protection.[64] The "Armada" installation, developed between 2017 and 2019, comprises approximately 35 to 45 mixed-media boats of varying sizes, suspended to form an evocative flotilla that critiques power structures through historical vessel archetypes, including colonial ships and contemporary refugee boats. Exhibited at institutions such as Tate Britain and Colby College Museum of Art, it highlights interconnected global narratives of conquest and displacement.[62][65][66] Other notable boat works include "The Wine Dark Sea" series, with pieces like "Boat X" acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, evoking Homeric seascapes through fantastical, adorned craft. In 2019, "Where Lies the Land" presented a new suspended boat installation inspired by Victorian poetry, connecting past fortunes to contemporary maritime perils. More recently, "Cargoes" (commissioned for the Thames Tideway Tunnel) features cast bronze boats referencing historical vessels tied to London's river trade, installed permanently along the waterway.[63][36][35] In 2025, Locke's "Odyssey" flotilla expanded this motif, sailing through representations of colonial history via painted and sculpted boats that interrogate post-colonial power dynamics. These installations consistently employ lightweight materials for aerial display, allowing shadows and movement to enhance the sense of precarious navigation.[67]Statue Interventions

Hew Locke's statue interventions typically involve temporary alterations or photographic reimaginings of public monuments tied to British imperialism, colonialism, and figures of power, using elements like fabrics, plastic objects, and sculptural additions to critique entrenched narratives without permanent damage.[68] These works emerged from early proposals for "statue-dressing" projects in London, which were rejected by institutions, leading Locke to develop conceptual series exploring "impossible proposals" for recontextualizing statues.[46] His approach, described by the artist as "mindful vandalism," employs painterly and sculptural modifications to destabilize dominant ideologies associated with these figures, often highlighting their links to empire and exploitation.[69] A pivotal early example is the Restoration series, commissioned by Spike Island for the British Art Show 6 in 2006 and focused on Bristol's contentious statues. Locke photographed four monuments—depicting slave trader Edward Colston, philosopher Edmund Burke, explorer John Cabot, and merchant Robert Sydenham—with overlaid interventions such as colorful drapery and plastic foliage, creating hybrid images that blend sculpture and photography to question their glorification of imperial history.[29] [70] The Colston image, in particular, predated the statue's toppling during 2020 Black Lives Matter protests by over a decade and reflected long-standing local campaigns against it, though Locke's proposals for physical redressing were not realized at the time.[71] These works underscore Locke's interest in non-destructive critique, pushing boundaries between media to evoke the statues' contested legacies amid Bristol's history of slave trade involvement.[72] In 2022, Locke executed Foreign Exchange in Birmingham's Centenary Square during the Commonwealth Games, encasing a statue of Queen Victoria in a monumental ship structure adorned with global currency motifs, sails, and navigational symbols to symbolize empire's maritime exploitation and economic entanglements.[73] This site-specific intervention transformed the monument—erected in 1901 to commemorate Victoria's diamond jubilee and diamond mining interests—into a vessel critiquing colonial resource extraction, drawing on Locke's childhood memories of passing a damaged Victoria statue in Guyana amid anti-colonial unrest.[74] The installation, which Locke had long envisioned as an "impossible proposal," temporarily disrupted the statue's pedestal, inviting public reflection on Britain's imperial past without defacement.[75] More recently, in November 2024, Locke announced a commission to intervene on a Brussels statue of King Leopold II, whose regime oversaw brutal exploitation in the Congo Free State, by installing five masts in front of the figure to evoke colonial shipping and domination.[76] This project extends his pattern of engaging European monuments linked to atrocities, using additive elements to foreground suppressed histories of violence and trade.[45] Across these interventions, Locke maintains a focus on layered symbolism—incorporating found plastics, ropes, and maritime iconography—to reveal power structures' fragility, prioritizing dialogue over destruction.[77]Recent Site-Specific Projects

In 2022, Hew Locke completed The Procession, a commissioned large-scale installation specifically designed for Tate Britain's Duveen Galleries in London.[78] The work consists of nearly 150 life-sized figures crafted from materials including foam, wood, wire mesh, and found objects, adorned with handmade garments, masks, and props that evoke themes of migration, protest, and carnival traditions.[15] [79] Installed from March 22, 2022, to January 15, 2023, the procession snakes through the neoclassical hall, drawing on historical events like Guyana's 1953 anti-colonial protests and the 2020 Black Lives Matter demonstrations to symbolize collective journeys across time and cultures.[78] [80] Later that year, Locke produced Gilt, a series of four temporary sculptures for the facade niches of The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Fifth Avenue building in New York.[22] Unveiled on September 15, 2022, and displayed until May 22, 2023, the cast fiberglass works, gilded to mimic precious metals, depict fragmented trophies and animal heads inspired by trophy-hunting artifacts in the Met's collection, such as elephant masks and ceremonial objects from Africa and Asia.[25] [81] The installation critiques the exercise of power, colonial acquisition, and institutional complicity in empire, with elements like faux-fur manes and beaded embellishments referencing specific Met holdings to highlight histories of exploitation.[82] [83] In 2025, Locke installed Cargoes, a permanent public commission for King Edward Memorial Park in London as part of the Thames Tideway Tunnel's art program.[35] Comprising six cast bronze boats embedded along a heritage trail in the park's landscape, the sculptures trace the River Thames' role in global trade, migration, and cultural exchange from ancient times to the present, incorporating motifs of vessels carrying goods, people, and symbolic cargoes like coins and bones.[84] Previewed on September 4, 2025, with full public access following park completion in July 2027, the work responds directly to the site's riverside location and Tideway's heritage strategy, embedding historical narratives into the urban environment.[84][85]Exhibitions and Commissions

Solo Exhibitions Timeline

- 1997: First UK solo exhibition at Gasworks, London, UK.[86]

- 2000: Hemmed In Two at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.[4]

- 2002: The Cardboard Palace at Chisenhale Gallery, London, UK.[4]

- 2004: King Creole on the facade of Tate Britain and at BBC New Media Village, London, UK.[4]

- 2004: House of Cards at Luckman Gallery, California State University, and Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, USA.[4]

- 2005: Hew Locke at The New Art Gallery Walsall, UK.[4]

- 2006: Restoration at St Thomas the Martyr's Church, Bristol, UK.[4]

- 2008: The Kingdom of the Blind at Rivington Place, London, UK.[4]

- 2011: For Those in Peril on the Sea at St. Mary & St. Eanswythe church as part of Folkestone Triennial, UK.[4]

- 2014: Give and Take, a performance in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern, London, UK, as part of Up Hill Down Hall.[4]

- 2015: The Tourists at HMS Belfast, London, UK.[4]

- 2019: Here's the Thing at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, UK, touring to Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri, USA, and Colby College Museum of Art, Maine, USA.[4][3]

- 2022: Gilt, facade commission at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA.[4][87]

- 2022: The Procession in the Duveen Hall at Tate Britain, London, UK.[4][87]

- 2022: Foreign Exchange at Victoria Square, Birmingham, UK.[87]

- 2023: The Ambassadors at The Lowry, Manchester, UK.[87]

- 2023: Listening to the Land at PPOW Gallery, New York, USA.[87]

- 2023: The Procession at The Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK (touring presentation).[87]

- 2024: Raw Materials at Almine Rech, Brussels, Belgium.[30][87]

- 2024: What Have We Here? at the British Museum, London, UK.[3][87]

- 2024: The Procession at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, Massachusetts, USA (touring presentation).[87]

- 2025: ARMADA at Newlyn Art Gallery, UK.[87]

- 2025: Gilt at Sculpture in the Park, Compton Verney, Warwickshire, UK.[87]

- 2025–2026: Passages at Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut, USA (opening 2 October 2025), with planned tours to Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio, USA, and Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas, USA in 2026.[3][87]