Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Matale

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

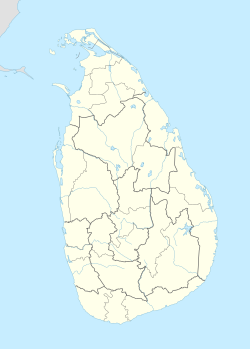

Matale (Sinhala: මාතලේ, IPA: [maːt̪əleː], Tamil: மாத்தளை, romanized: Māttaḷai, IPA: [maːt̪ɐɭɛi̯]) is a major city in Central Province, Sri Lanka. It is the administrative capital and largest urbanised city of Matale District. Matale is also the second largest urbanised and populated city in Central Province. It is located at the heart of the Central Highlands of the island and lies in a broad, green fertile valley at an elevation of 364 m (1,194 ft) above sea level. Surrounding the city are the Knuckles Mountain Range, the foothills were called Wiltshire by the British. They have also called this place as Matelle.[4][5][6]

Key Information

History

[edit]Matale is the only district of Sri Lanka where an ancient book of written history is found. It is known as Pannagamam – பன்னாகமம் ("Five Headed Serpent" in English) of Goddess Muthumari in Sri Muthumariamman Temple.

The most important historical incident in Matale is the writing of the Thripitaka during the reign of King Walagamba in 89–77 BC in Aluvihare. It is mentioned that "Mahatala" become the modern word Matale because it is placed in a valley and also the King Gajaba invaded "Soli Rata" and brought and settled 12,000 people here.[7]

The Aluvihare Rock Temple that is situated on north side of the city's suburb, Aluvihare. The historic location where the Pali Canon was written down completely in text on ola (palm) leaves in 29 BCE.[citation needed]

Matale was the site of a major battle in 1848 when the Matale Rebellion started and the British garrison in the Fort MacDowall in Matale was placed under siege by the rebels led by Weera Puran Appu and Gongalegoda Banda.[citation needed]

The city is also the birthplace of Monarawila Keppetipola, a rebel who led the Wellasa rebellion against the British troops. His ancestral home, Kappetipola walawuwa, still exists at Hulangamuwa, Matale.[citation needed]

Attractions

[edit]- Aluvihare Rock Temple

- Anagarika Dharmapala monument

- Christ Church, Matale

- Fort MacDowall

- Matale clock tower

- Matale railway station, the former terminus of the Colombo railway (completed in 1880)

- Sri Muthumariyamman Temple

- Nandamithra Ekanayake International Hockey Ground

- Weera Monarawila Keppetipola Monument

- Weera Puranappu Monument

Economy

[edit]The city is surrounded by large plantations and is famous for its spice gardens. In addition to agriculture, the main economic activities include tourism, business and trade. Population growth, urban expansion and economic development in Matale have created regulatory and management challenges.[8][9]

Education

[edit]Matale is home to some of the island's oldest and leading colleges and schools.

- Government Science College

- Amina Girl's National School, Matale

- Christ Church College, Matale

- Greenwood College International, Matale

- Matale Hindu College, Matale

- Matale International School

- Pakkiyam National School, Matale

- Royal English School Matale

- St. Thomas' College, Matale

- St. Thomas' Girls' School, Matale

- Sinhala Buddhist College, Matale

- Sri Sangamitta Balika National School, Matale

- Sujatha Balika School, Matale

- Technical College, Matale

- Vijaya College, Matale

- Vijayapala Collage, Matale

- Zahira College, Matale

Demographics

[edit]According by the statistics of 2019, 8.2% of the population of Matale District live in the Matale city limits and 15% of the population of the district live in Matale metropolis.[10] Matale is a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural city, city's urban and metro area's residents are mix of numerous ethnic groups. The Sinhalese make the majority of the city. Muslims are the second largest ethnic group in the city. Others include Sri Lankan Tamils, small numbers of Indian Tamils, Burghers and Malays.

Source:statistics.gov.lk

Ethnicity in Metropolis Area

[edit]Source:statistics.gov.lk

Suburbs

[edit]- Agalawatta (MC)

- Aluvihare (MC)

- Hulangamuwa (MC)

- Kaludewala (MC)

- Mandandawela (MC)

- Palapathwela (PS)

- Ukuwela (PS)

- Yatawatta (PS)

Notable personalities

[edit]- Alick Aluwihare, politician

- A. S. Jayawardena, Governor Central Bank of Sri Lanka

- Chanaka Welegedara, International cricketer

- Damith Wijayathunga, model and actor

- Dayan Witharana, singer and photographer

- Ehelepola Nilame, a minister in King Sri Vikrama Rajasinha's royal court

- Hemal Ranasinghe, model and actor

- Keppetipola Disawe, leader of the Great Rebellion of Uva in 1818

- Kingsley Jayasekera, actor and singer

- Kumar Sangakkara, International cricketer

- Lahiru Madushanka, International cricketer

- Prabath Jayasuriya, International cricketer

- Ven. Premananda, Hindu guru

- Richard Aluwihare, first Ceylonese Inspector General of Police

- Richard Udugama, first Sinhalese Buddhist Army Commander

- Sanath Wimalasiri, dramatist and dancer

- Gen. Shavendra Silva, Commander of the 58 Division during the Sri Lankan Civil War, current Commander of the Sri Lanka Army

- William Gopallawa, last Governor-General of Ceylon and first president of Republic of Sri Lanka

References

[edit]- ^ "NPP secures power in Matale Municipal Council".

- ^ "District Secretariat – Matale".

- ^ "Kandy DIG promoted". 19 August 2020.

- ^ "CEYLON. (Hansard, 27 May 1851)". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ Tennent, James Emerson (1860). Ceylon: An account of the island. Physical, hist., and topographical with notices of its natural history, antiquities and productions. Illustr. by maps, pl. and drawings. Longman.

- ^ Ferguson, John (1893). Ceylon in 1893 describing the progress of the Island since 1803, its present agricultural and commercial enterprises and its unequalled attractions to visitors. John Huddon, London.

- ^ "Divisional Secretariat – Matale – About Us". matale.ds.gov.lk. Retrieved 8 November 2021.

- ^ Gamage, Nardda; Kumara, Sisira (31 December 2016). "Socio-Economic Determinants of Well-Being of Urban Households: A Case of Sri Lanka". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2938379.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Atapattu, A; Subasinghe, Shyamantha; Iwai, Y (24 August 2019). "Urban Growth and Development Pattern of Matale Municipal Council Area".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Details – Department of Health Services : Central Province, Sri Lanka". healthdept.cp.gov.lk. Retrieved 30 April 2023.

External links

[edit]Matale

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Topography

Matale is situated in the Central Province of Sri Lanka, serving as the capital of Matale District. The town lies at geographic coordinates approximately 7.47° N latitude and 80.62° E longitude.[10] It is positioned within the northern part of the Central Province, encompassing a district area bounded by roughly 7.38° to 8.01° N and 80.50° to 80.99° E.[11] The topography of Matale features a broad, fertile valley at an elevation of about 358 meters above sea level.[10] This valley is embedded in the Central Highlands, characterized by rolling hills and undulating terrain that transitions into more rugged landscapes eastward. The surrounding region includes foothills of the Knuckles Mountain Range, which contribute to a varied elevation profile across the district, averaging around 270 meters but rising significantly in mountainous areas.[12][13] The Knuckles Range, a prominent topographic feature to the east of Matale, forms part of the district's eastern boundary and is noted for its steep escarpments, deep valleys, and high biodiversity, with peaks exceeding 1,800 meters.[5] This mountainous backdrop influences local drainage patterns, with rivers and streams originating from the highlands flowing through the valley, supporting agricultural fertility in the lower elevations.[14]Climate and Environmental Features

Matale District features a tropical monsoon climate typical of Sri Lanka's Central Province, with consistently warm temperatures and bimodal rainfall patterns driven by the southwest (Yala) and northeast (Maha) monsoons. Average annual temperatures range from a minimum of 18.9°C to a maximum of 32.9°C, with a yearly mean of approximately 24.1°C.[15][16] The district's intermediate rainfall zone receives total annual precipitation of 1,746 mm to 1,868 mm, with peak rainfall during the inter-monsoon periods in May–June and October–November, and lower amounts in the drier months of January–February and July–August.[17][16] Elevations from 300 m to over 1,800 m in the Knuckles Range create microclimatic variations, with higher altitudes experiencing cooler temperatures and increased orographic rainfall compared to lowland areas. Humidity levels remain high year-round, averaging 75–85%, contributing to misty conditions in forested uplands.[18] The climate supports agriculture, including tea, spices, and vegetables, but episodic droughts and floods—exacerbated by El Niño events—have impacted yields, as recorded in meteorological data from nearby stations. Environmentally, Matale is a biodiversity hotspot, with natural forests covering 63% of its approximately 2,000 km² land area as of 2020, encompassing montane, sub-montane, lowland evergreen, and moist monsoon forest types.[19][20] The Knuckles Mountain Range, spanning much of the district's eastern sector, hosts diverse ecosystems due to its steep gradients and varied rainfall, supporting endemic flora such as Dipterocarpus species and fauna including the purple-faced leaf monkey and several amphibian endemics.[18][5] However, forest loss has occurred at a rate of about 250 hectares annually in recent years, primarily from agricultural expansion and logging, reducing carbon stocks equivalent to 115 kt CO₂ emissions in 2024 alone.[19] Conservation efforts, including protected areas like the Knuckles Forest Reserve, aim to preserve this habitat connectivity amid pressures from human settlement.[18]History

Ancient and Pre-Colonial Period

Archaeological surveys in the Matale District have uncovered prehistoric tools and artifacts, indicating human habitation in the central highlands dating back to the Mesolithic period, with evidence of early hunter-gatherer communities similar to those found across Sri Lanka's upland regions.[21] These findings suggest the area served as a resource-rich zone for indigenous groups, including proto-Vedda populations, prior to organized settlements, though specific dating for Matale sites remains approximate due to limited excavation depth compared to coastal or northern areas.[22] The advent of Buddhism in the 3rd century BCE marked a pivotal shift, with King Devanampiyatissa establishing early monastic complexes in the region, including the foundational structures at Aluvihara Rock Temple near Matale town. This site, featuring cave dwellings and a stupa, became a center for Theravada monasticism, with inscriptions and architectural remnants confirming royal patronage during the Anuradhapura Kingdom's expansion.[23] Further significance arose in the 1st century BCE under King Vattagamani Abhaya, when, amid invasions and famine, Buddhist monks at Aluvihara committed the oral Tripitaka to palm-leaf manuscripts for the first time, preserving doctrinal continuity against external threats—a causal mechanism rooted in the vulnerability of memorized teachings to disruption.[23] In the early historic period, Matale's strategic hill terrain integrated it into broader Sinhalese polities, with sites like Dambulla Cave Temple (dating to the 1st century BCE) evidencing continued royal endowments and iconographic development under Anuradhapura and subsequent Polonnaruwa influences. By the 5th century CE, the district hosted monumental projects such as Sigiriya, where King Kashyapa I constructed a rock fortress and hydraulic complex as a temporary capital, reflecting defensive imperatives amid dynastic strife; engineering feats like cisterns and frescoes underscore resource mobilization in the upland interior.[6] Pre-colonially, from the medieval era onward, Matale formed a core territory of the Kandyan Kingdom (established circa 1469 CE), serving as a buffer in the central highlands against lowland incursions. Administrative records delineate Matale as a disavani (provincial division) under Kandyan monarchs, with local chiefs managing agrarian economies centered on paddy, spices, and forest resources, sustaining the kingdom's autonomy until the early 19th century. This period emphasized feudal hierarchies and resistance to maritime powers, with Matale's terrain facilitating guerrilla defenses, as evidenced in boundary delineations tying villages to royal service obligations.[24]Colonial Era and Matale Rebellion

The British established control over Matale and the broader Kandyan interior, including the former Kingdom of Kandy, through the Kandyan Convention signed on 2 March 1815, which deposed the last king, Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, and annexed the territory without immediate large-scale resistance.[22] Under Governor Robert Brownrigg, the British initially maintained some Kandyan customs to secure loyalty from local chiefs (radala), but administrative reforms under the Colebrooke-Cameron Commission of 1833 centralized governance, abolished the traditional rajakariya (corvée labor) system in favor of wage labor, and imposed new land and grain taxes to fund infrastructure and plantations.[25] These changes, combined with the expansion of coffee cultivation from the 1840s—which appropriated communal lands (purana gala) for European estates—exacerbated peasant hardships in Matale district, where smallholders faced eviction, debt, and compulsory road labor under the Road Ordinance of 1842.[26] Discontent intensified in 1848 amid Ceylon's economic downturn, as falling coffee prices prompted Governor Henry Ward (later Viscount Torrington) to introduce revenue measures on 1 July, including license fees on guns, dogs, carts, and shops, plus mandatory unpaid labor on plantation roads unless a commutation tax was paid.[27] These policies, affecting an estimated 200,000 Kandyan peasants already strained by prior taxes yielding £150,000 annually for the colonial treasury, sparked widespread unrest rooted in both economic grievance and lingering aspirations for Sinhalese Buddhist monarchy restoration, influenced by bhikkus (monks) and chiefs disaffected since the 1818 Uva-Wellassa revolt.[25][28] The Matale Rebellion erupted on 26 July 1848, when approximately 4,000 rebels, armed with muskets, knives, and sticks, gathered at Dambulla Viharaya, where Gongalegoda Banda—a charismatic leader from the area—was ritually consecrated as king at 11:30 a.m., with Veera Puran Appu (from Kegalle) appointed as prime minister and sword-bearer, Dines as sub-king, and Dingirirala as a regional commander.[27] The insurgents aimed to seize Kandy and expel the British; on 28 July, they attacked the Matale Kachcheri (government office), destroying tax records, while a separate force under Dines struck the Waryapola coffee estate near Kurunegala, killing eight Europeans and Sinhalese collaborators.[27] Further skirmishes targeted police posts and estates across Sat Korale and Matale, but the rebels' lack of artillery and organization limited their advance against British regulars and militia. British forces, numbering about 1,500 troops including the 78th Highlanders, suppressed the uprising by early August through superior firepower and intelligence from loyal chiefs, capturing Puran Appu after a betrayal; he was tried by court-martial and executed by firing squad on 8 August 1848 in Matale.[29] Gongalegoda Banda evaded capture initially, continuing guerrilla actions until November, when he was apprehended and sentenced to life transportation to Mauritius on 27 November 1848, dying in exile on 1 December 1849.[25] The rebellion resulted in over 100 rebel deaths and 26 executions, including leaders like Dingirirala, but prompted minor tax relief and highlighted colonial vulnerabilities, though British records framed it as banditry rather than nationalist revolt.[25] A memorial pillar in Matale town later commemorates the event as a symbol of anti-colonial resistance.[27]Post-Independence Developments

Following Sri Lanka's independence on February 4, 1948, Matale district solidified its role as an agricultural hub within the Central Province, emphasizing spice production, gem mining, and plantation crops such as rubber and vegetables, which supported national exports amid broader economic shifts toward import substitution and rural development initiatives.[22] The area's spice gardens and gem trade expanded post-war, leveraging historical expertise to contribute to Sri Lanka's agro-based economy, though urban commercial growth in Matale town lagged due to low population density and limited industrialization.[30] The district faced significant political turbulence during the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) insurrections. The 1971 uprising, led by Marxist youth in southern and central regions, disrupted local stability, with armed clashes and government crackdowns affecting rural communities in Matale.[31] The more violent 1987–1989 insurrection saw intensified JVP activity in the upcountry, prompting harsh counter-insurgency measures; operations in Matale allegedly resulted in hundreds of enforced disappearances and extrajudicial actions by security forces, including under then-military officer Gotabaya Rajapaksa, contributing to an estimated 40,000 deaths nationwide.[32][33] In recent decades, development efforts have focused on tourism tied to cultural sites like Aluvihara Rock Temple and nearby cave monasteries, alongside modest infrastructure upgrades, though Matale continues to grapple with urban shrinkage, inadequate public facilities, and uneven economic progress compared to coastal provinces.[34][35] These challenges reflect national patterns of regional disparities, with Matale's economy remaining predominantly agrarian despite policy pushes for diversification.[36]Administration and Politics

Local Governance Structure

The Matale Municipal Council (MMC) serves as the principal local authority overseeing urban administration in Matale, Sri Lanka's Central Province. Established pursuant to the Municipal Councils Ordinance, the MMC manages essential services including waste collection, public health enforcement, road maintenance, street lighting, market regulation, and building approvals within its jurisdictional boundaries, which encompass the city's core urban zones.[37] The council operates under the oversight of the Ministry of Provincial Councils and Local Government, ensuring alignment with national policies while addressing locality-specific needs.[38] Elections for the MMC occur every four years, coordinated by the Election Commission of Sri Lanka, utilizing a mixed electoral system: 60% of seats are contested via first-past-the-post in designated wards, while the remaining 40% are allocated proportionally based on party vote shares to reflect broader electorate preferences.[39] Post-election, council members convene to elect the mayor and deputy mayor by majority vote, with the mayor assuming ceremonial and executive leadership roles, such as chairing meetings and representing the council in official capacities. Administrative operations, including budget execution and departmental oversight, fall under the appointed Municipal Commissioner, supported by specialized units for engineering, sanitation, revenue collection, and legal affairs. In the local government elections of May 6, 2025, the MMC's composition was renewed amid national shifts, with the National People's Power (NPP) emerging dominant; on June 23, 2025, NPP councillor Ashoka Kottahachchi was elected mayor, securing 12 votes in the council ballot.[40] This structure integrates elected representation with bureaucratic efficiency, though challenges like resource constraints and coordination with the broader Matale District—governed partly by divisional secretariats and adjacent pradeshiya sabhas for rural peripheries—persist in service delivery.[41]Electoral Outcomes and Political Dynamics

In the 2024 Sri Lankan parliamentary election held on November 14, the Jathika Jana Balawegaya (NPP) achieved a commanding victory in Matale District, securing 181,678 votes or 66.16% of the valid votes cast, translating to 4 of the district's 5 seats under the proportional representation system.[42] The Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) followed with 53,200 votes (19.37%), earning 1 seat, while the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) received only 10,150 votes (3.70%) with no seats.[42] This outcome marked a significant departure from the 2020 election, where the SLPP had dominated with 188,779 votes (65.53%) and 4 seats, reflecting national disillusionment with established parties following the 2022 economic crisis.[42] Local elections for the Matale Municipal Council on May 6, 2025, further underscored NPP's rising influence, with the party winning 7,476 votes (40.64%) and 10 of 22 seats.[43] The SJB secured 5,571 votes (30.28%) and 6 seats, while smaller parties like the Ceylon Workers' Congress (1,571 votes, 8.54%, 2 seats) and SLPP (803 votes, 4.36%, 1 seat) trailed.[43] Voter turnout was approximately 59%, with 18,846 polled out of 31,888 registered electors.[43]| Election | Date | NPP Votes (%) / Seats | SJB Votes (%) / Seats | SLPP Votes (%) / Seats |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parliamentary (Matale District) | Nov 14, 2024 | 181,678 (66.16%) / 4 | 53,200 (19.37%) / 1 | 10,150 (3.70%) / 0 |

| Local (Matale MC) | May 6, 2025 | 7,476 (40.64%) / 10 | 5,571 (30.28%) / 6 | 803 (4.36%) / 1 |