Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Keyboard shortcut

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2010) |

In computing, a keyboard shortcut (also hotkey/hot key or key binding)[1] is a software-based assignment of an action to one or more keys on a computer keyboard. Most operating systems and applications come with a default set of keyboard shortcuts, some of which may be modified by the user in the settings.

Keyboard configuration software allows users to create and assign macros to key combinations which can perform more complex sequences of actions. Some older keyboards had a physical macro key specifically for this purpose.

Terminology

[edit]The precise words used for these assignments and their meaning can vary depending on the context.

For example, Microsoft has generally used keyboard shortcuts for Windows[2] and Microsoft Office[3] since the transition to 64-bit for Windows 7. However, they used hot keys prior to that and continue to do so in their 32-bit API for developing 'classic desktop apps'.[4][5][6] Meanwhile, Lenovo and ASUS each have keyboard configuration software made for Windows that are named "Lenovo Hotkeys"[7] and "ASUS Keyboard Hotkeys"[7] respectively.

The assignment process is referred to as mapping the actions to the keys, and changing them afterwards is therefore remapping.[8][9] The assigned action is then said to be bound to the key, leading to the phrase key binding being used interchangeably with shortcut and hotkey.[10]

As other input devices became increasingly configurable in the early 2000's, the term shortcut began to be used to refer to what are essentially keyboard shortcuts being mapped to objects that are not keyboard keys. The most prevalent of these are computer mice, which went from only having two buttons for left and right clicks to having additional buttons on the around the side, top, and back of the mice (2-4 for common usage and up to 12 extra programmable buttons for certain types of gaming uses).[11]

As Internet of things (IoT) devices continue to proliferate, shortcuts are appearing in many other device types such as electronic keyboards, home automation devices, wearable technology, and more.

Human-computer interaction experts also continue to design new types of shortcuts altogether, such as gestures on touchscreens and touchless interfaces.

Description

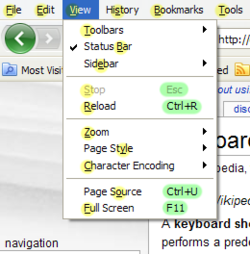

[edit]Keyboard shortcuts are typically a means for invoking one or more commands using the keyboard that would otherwise be accessible only through a menu, a pointing device, different levels of a user interface, or via a command-line interface. Keyboard shortcuts are generally used to expedite common operations by reducing input sequences to a few keystrokes, hence the term "shortcut".[12]

To differentiate from general keyboard input, most keyboard shortcuts require the user to press and hold several keys simultaneously or a sequence of keys one after the other. Unmodified key presses are sometimes accepted when the keyboard is not used for general input - such as with graphics packages e.g. Adobe Photoshop or IBM Lotus Freelance Graphics. Other keyboard shortcuts use function keys that are dedicated for use in shortcuts and may only require a single keypress. For simultaneous keyboard shortcuts, one usually first holds down the modifier key(s), then quickly presses and releases the regular (non-modifier) key, and finally releases the modifier key(s). This distinction is important, as trying to press all the keys simultaneously will frequently either miss some of the modifier keys, or cause unwanted auto-repeat. Sequential shortcuts usually involve pressing and releasing a dedicated prefix key, such as the Esc key, followed by one or more keystrokes.

Mnemonics are distinguishable from keyboard shortcuts. One difference between them is that the keyboard shortcuts are not localized on multi-language software but the mnemonics are generally localized to reflect the symbols and letters used in the specific locale. In most GUIs, a program's keyboard shortcuts are discoverable by browsing the program's menus – the shortcut is indicated next to the menu choice. There are keyboards that have the shortcuts for a particular application already marked on them. These keyboards are often used for editing video, audio, or graphics,[13] as well as in software training courses. There are also stickers with shortcuts printed on them that can be applied to a regular keyboard. Reference cards intended to be propped up in the user's workspace also exist for many applications. In the past, when keyboard design was more standardized, it was common for computer books and magazines to print cards that were cut out, intended to be placed over the user's keyboard with the printed shortcuts noted next to the appropriate keys.

Customization

[edit]

When shortcuts are referred to as key bindings, it carries the connotation that the shortcuts are customizable to a user's preference and that program functions may be 'bound' to a different set of keystrokes instead of or in addition to the default.[14] This highlights a difference in philosophy regarding shortcuts. Some systems, typically end-user-oriented systems such as Mac OS or Windows, consider standardized shortcuts essential to the environment's ease of use. In these commercial proprietary systems, the ability to change the default bindings and add custom ones can be limited, possibly even requiring a separate or third-party utility to perform the task, sometimes with workarounds like key remapping. In macOS, user can customize app shortcuts ("Key equivalents") in system settings, and customize text editing shortcuts by creating and editing related configuration files.[15] Other systems, typically Unix and related, consider shortcuts to be a user's prerogative, and that they should be customizable to suit individual preference. In most real-world environments, both philosophies co-exist; a core set of sacred shortcuts remain fixed while others, typically involving an otherwise unused modifier key or keys, are under the user's control.

The motivations for customizing key bindings vary. Users new to a program or software environment may customize the new environment's shortcuts to be similar to another environment with which they are more familiar.[16] More advanced users may customize key bindings to better suit their workflow, adding shortcuts for their commonly used actions and possibly deleting or replacing bindings for less-used functions.[17] Hardcore gamers often customize their key bindings in order to increase performance via faster reaction times.

Reserved Keyboard Shortcuts

[edit]The original Macintosh User Interface Guidelines defined a set of keyboard shortcuts that would remain consistent across application programs.[18] This provides a better user experience than the then-prevalent situation of applications using the same keys for different functions. This could result in user errors if one program used ⌘ Command+D to mean Delete while another used it to Duplicate an item. The standard bindings were:

- ⌘ Q : Quit

- ⌘ W : Close Window

- ⌘ B : Bold text

- ⌘ I : Italicize text

- ⌘ U : Underline text

- ⌘ O : Open

- ⌘ P : Print

- ⌘ A : Select All

- ⌘ S : Save

- ⌘ F : Find

- ⌘ G : Find Again (the G key is next to the F key on a QWERTY keyboard)

- ⌘ E : Enter search string from selection (allowed searching a document by selecting text and typing ⌘ E⌘ G (exempli gratia)

- ⌘ Z : Undo (represents the do-undo-redo cycle)

- ⌘ X : Cut (resembles scissors or a general sign for removal – and the X key is next to the C key on a QWERTY keyboard)

- ⌘ C : Copy

- ⌘ V : Paste (resembles the proofreader's mark for "insert" – and the V key is next to the C key on a QWERTY keyboard)[19]

- ⌘ N : New Document

- ⌘ . (full stop): User interrupt[notes 1], it can be used to close dialogs, search bars, and context menus.

- ⌘ ? : Help (? signifies a question or confusion)[20]

Later environments such as Microsoft Windows retain some of these bindings, while adding their own from alternate standards like Common User Access. The shortcuts on these platforms (or on macOS) are not as strictly standardized across applications as on the early Macintosh user interface, where if a program did not include the function normally carried out by one of the standard keystrokes, guidelines stated that it should not redefine the key to do something else as it would potentially confuse users.[21]

Notation

[edit]The simplest keyboard shortcuts consist of only one key. For these, one generally just writes out the name of the key, as in the message "Press F1 for Help". The name of the key is sometimes surrounded in brackets or similar characters. For example: [F1] or <F1>. The key name may also be set off using special formatting (bold, italic, all caps, etc.)

Many shortcuts require two or more keys to be pressed simultaneously. For these, the usual notation is to list the keys names separated by plus signs or hyphens. For example: "Ctrl+C", "Ctrl-C", or "Ctrl+C". The Ctrl key is sometimes indicated by a caret character (^). Thus Ctrl-C is sometimes written as ^C. At times, usually on Unix platforms, the case of the second character is significant – if the character would normally require pressing the Shift key to type, then the Shift key is part of the shortcut e.g. '^C' vs. '^c' or '^%' vs. '^5'. ^% may also be written "Ctrl+⇧ Shift+5".

Some keyboard shortcuts, including all shortcuts involving the Esc key, require keys (or sets of keys) to be pressed individually, in sequence. These shortcuts are sometimes written with the individual keys (or sets) separated by commas or semicolons. The Emacs text editor uses many such shortcuts, using a designated set of "prefix keys" such as Ctrl+C or Ctrl+X. Default Emacs keybindings include Ctrl+X Ctrl+S to save a file or Ctrl+X Ctrl+B to view a list of open buffers. Emacs uses the letter C to denote the Ctrl key, the letter S to denote the Shift key, and the letter M to denote the Meta key (commonly mapped to the Alt key on modern keyboards.) Thus, in Emacs parlance, the above shortcuts would be written C-x C-s and C-x C-b. A common backronym for Emacs is "Escape Meta Alt Ctrl Shift", poking fun at its use of many modifiers and extended shortcut sequences.

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Technical note: it calls the AppKit method "cancelOperation:"

- ^ "Google Books Ngram Viewer". books.google.com. 2024-10-19. Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ "Keyboard shortcuts in Windows - Microsoft Support". support.microsoft.com. Microsoft. Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ "Customize keyboard shortcuts - Microsoft Support". support.microsoft.com. Microsoft. Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ "About Hot Key Controls - Win32 apps". learn.microsoft.com. Microsoft. 2021-05-25. Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ "Overview of framework options - Windows apps". learn.microsoft.com. Microsoft. 2024-09-10. Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ "How do I reassign hot keys for my keyboard? - Microsoft Support". support.microsoft.com. Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ a b "ASUS Keyboard Hotkeys - Free download and install on Windows". Microsoft Store. ASUS. 2017-10-19. Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ "How to Remap Your Keyboard | Windows Learning Center". Windows. Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ "Shortcuts, Hotkeys, Macros, Oh My: How to Remap Your Keyboard". PCMAG. 24 April 2024. Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ "Key Bindings for Visual Studio Code". code.visualstudio.com/docs. Microsoft. 2024-10-03. Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ "The Best MMO Mouse - Fall 2024: Mice Reviews". RTINGS.com. Retrieved 2024-10-19.

- ^ In the English language a "shortcut" may unintentionally suggest an incomplete or sloppy way of completing something. Consequently, some computer applications designed to be controlled mainly by the keyboard, such as Emacs, use the alternative term "key binding".

- ^ Lowensohn, Josh (3 December 2009). "Hardware for Gmail: The 'Gboard' keyboard". CNET.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- ^ "GNU Emacs Manual: Commands".

Emacs does not assign meanings to keys directly. Instead, Emacs assigns meanings to named commands, and then gives keys their meanings by binding them to commands.

- ^ "Text System Defaults and Key Bindings". Apple Developer Documentation Archive. September 9, 2013. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved 2024-01-18.

- ^ Cohen, Sandee (2002). Macromedia FreeHand 10 for Windows and Macintosh. Peachpit Press. ISBN 9780201749656.

- ^ "Customizing your keyboard shortcuts".

- ^ Apple (November 1992). Macintosh Human Interface Guidelines (PDF). Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. p. 128. ISBN 0-201-62216-5.

- ^ "Larry Tesler email Past to Future: Various Undo Models, Interaction Histories, and Macro Recording Lecture 21".

- ^ "Definition of QUESTION". www.merriam-webster.com.

- ^ "OS X Human Interface Guidelines".

If your app does not perform the task associated with a recommended shortcut, think very carefully before you consider overriding it. Remember that although reassigning an unused shortcut might make sense in your app, your users are likely to know and expect the original, established meaning.

Keyboard shortcut

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

A keyboard shortcut is a combination of one or more keys pressed simultaneously or in rapid succession on a computer keyboard to execute a predefined command or function within software applications or operating systems.[13] This approach allows users to bypass menu selections or graphical navigation, enhancing efficiency by directly mapping key sequences to actions such as copying text or saving files.[14] The concept of keyboard shortcuts originated in the 1970s at Xerox PARC, where researchers developed them for early graphical user interfaces (GUIs) on systems like the Xerox Alto, marking a shift from command-line inputs to more intuitive interactions.[15] By the 1980s, with the commercialization of GUIs in products like the Xerox Star and the Apple Macintosh, keyboard shortcuts became integral to replacing slower menu-based navigation, promoting productivity in personal computing environments.[16] These innovations laid the groundwork for widespread adoption, as they enabled rapid command invocation without relying on pointing devices.[17] Unlike mouse gestures, touch inputs, or voice commands, keyboard shortcuts depend solely on physical keystrokes to activate system-defined responses, distinguishing them as a keyboard-centric method for direct software control.[18]Terminology

In technical discussions, several terms are used interchangeably with "keyboard shortcut" to describe sequences of keystrokes that invoke commands. A "hotkey" typically refers to a single key or simple multi-key combination assigned to perform an action, often emphasizing its immediate responsiveness in user interfaces.[14] An "accelerator key" denotes a shortcut designed to expedite access to menu-based commands, allowing users to bypass graphical navigation. Similarly, a "mnemonic" describes a shortcut that employs a letter or symbol logically related to the command it activates, such as pressing 'S' to invoke a Save function, aiding memorability in applications.[20] Variations in terminology arise across contexts and regions, reflecting different emphases in software design. Terms like "keyboard combination" or "key binding" are frequently used as synonyms, with "key binding" particularly prevalent in programming and development environments to highlight the explicit assignment of keys to functions within code or configurable systems. These alternatives underscore the flexibility of the concept without altering its core function as a command invoker. The vocabulary has evolved alongside computing paradigms, shifting from early "control key sequences" prevalent in command-line interfaces—such as Ctrl+C to interrupt processes in Unix-like systems during the 1970s[21]—to contemporary "global shortcuts" that function across the entire operating system, independent of the active application. This progression mirrors the transition from text-based terminals to graphical user interfaces, where broader applicability became essential. The foundational control sequences originated in pioneering work at Xerox PARC in the mid-1970s, influencing standards like cut, copy, and paste operations.[5]Functionality

Mechanism

Keyboard input detection in computing environments initiates at the hardware level, where the keyboard's embedded microcontroller periodically scans its key matrix—a grid of switches representing each key—to identify presses and releases. Upon detection, the microcontroller generates a scan code, a device-specific numeric identifier for the key's physical position (e.g., scan code 0x1E for the 'A' key in PS/2 set 2). These scan codes are serialized and transmitted to the host computer via interface protocols such as PS/2 or USB HID, typically triggering a hardware interrupt request (IRQ) to notify the CPU of new input without constant polling. In legacy PS/2 systems, the AT keyboard controller manages this via IRQ1, reading data from I/O port 0x60 after the interrupt and checking parity in the 11-bit serial frame (start bit, 8 data bits, parity bit, stop bit).[22] The operating system's keyboard driver then processes these interrupts through dedicated handlers in the kernel. The driver translates the raw, hardware-dependent scan codes into virtual key codes—standardized, device-independent values that represent the key's function regardless of layout (e.g., VK_RETURN for Enter). In Windows, this mapping occurs in the HID-class keyboard driver, which also tracks modifier states (e.g., Shift or Alt) using keyboard state flags like KF_SHIFTED, producing low-level keystroke messages such as WM_KEYDOWN or WM_KEYUP with associated repeat counts for held keys. Similarly, in Linux, the kernel's input core subsystem (evdev) receives scan codes via drivers like i8042 for PS/2 or usbhid for USB, mapping them to keycodes through loadable keymap tables (e.g., via /lib/udev/keymap/) before emitting input events to user space. This translation ensures portability across diverse hardware while filtering noise like debouncing delays.[23][24] Once translated, the execution flow for keyboard shortcuts involves matching the sequence of virtual key codes against predefined combinations within the system's event processing pipeline. The OS dispatches input events to the foreground application or window manager via message queues or event buses, where modifier flags indicate combinations (e.g., Ctrl+Alt+Del). If a match is detected—often in real-time during the interrupt service routine or input thread—the system invokes an associated event handler, directly executing the bound function such as closing a window or switching tasks. This handler typically bypasses higher-level GUI text processing (e.g., avoiding WM_CHAR conversion) for performance, allowing sub-millisecond response times critical for responsive interfaces. In Windows, global shortcuts registered via the RegisterHotKey API trigger WM_HOTKEY messages to the registering thread, while application-local checks occur in the window procedure's message loop.[23] Processing occurs across layered architectures to support interception at varying scopes. At the hardware/firmware level, the keyboard's microcontroller handles rudimentary tasks like generating break codes for key releases (e.g., scan code +0x80) but lacks capacity for complex logic, deferring to the host. Software interception divides into kernel-level handling—where drivers and subsystems like Windows' Win32k.sys or Linux's input layer enforce security and mapping—and user-space levels, where applications or desktop environments (e.g., via X11 or Wayland event loops) monitor events for custom actions. This stratification enables efficient routing: kernel layers filter invalid inputs early, while user-space allows modular extension without kernel modifications.[22][23][24]Types

Keyboard shortcuts are categorized into various types based on their structure, the scope in which they operate, and specialized behaviors that adapt to user context or input patterns. These classifications help in understanding how shortcuts are designed and implemented to enhance user efficiency across different computing environments.Structural Types

Structural types refer to the way keys are pressed to activate a shortcut. Single-key shortcuts involve pressing one key alone to trigger an action, such as the F1 key to access help documentation in many applications.[25] These are straightforward and commonly assigned to function keys or dedicated hardware buttons for quick, unmodified access. Chorded shortcuts, also known as key combinations, require pressing multiple keys simultaneously, typically involving modifier keys like Ctrl, Alt, or Shift alongside a primary key; for example, Ctrl+C to copy selected content.[26] This type leverages the keyboard's ability to detect concurrent presses, allowing for a compact set of commands without overwhelming the available key space.[27] In contrast, sequential shortcuts, or key sequences, involve pressing keys one after another in a specific order, often starting with a modifier and followed by additional keys, such as C-x followed by C-f to open a file in GNU Emacs.[28] This approach enables more complex commands by chaining inputs, which is particularly useful in environments with a high volume of actions, though it may require users to memorize the order.[27]Scope Types

The scope of a keyboard shortcut determines its availability and precedence across the system. Application-specific shortcuts function only within a particular software program, allowing developers to define custom bindings tailored to the app's workflow without interfering with other tools.[29] For instance, they might activate unique features like formatting options in a text editor but remain inactive elsewhere. System-wide shortcuts, also called global shortcuts, operate across the entire operating system and multiple applications, providing consistent access to core functions such as switching between open windows.[29] These are typically reserved by the OS to ensure uniformity and prevent conflicts, with examples including combinations that launch system menus or file explorers. Hardware-level shortcuts are defined at the firmware or device level, independent of the operating system or software, often handling multimedia controls or power functions directly through the keyboard's embedded controller.[30] Such shortcuts, like those for volume adjustment on dedicated keys, are processed by the keyboard's microcontroller before signals reach the host system, enabling reliable operation even in low-level boot environments.[31]Specialized Types

Specialized types extend basic structures with adaptive or multi-step elements. Multi-step sequential shortcuts incorporate sequences that execute layered commands, such as a series of key presses to navigate nested menus.[27] These are designed for more complex interactions in advanced input systems. Context-sensitive shortcuts vary their behavior based on the active window, mode, or selected element, allowing the same key combination to perform different actions depending on the current focus; for example, a shortcut might resize objects in a drawing tool but adjust layout in a text processor.[25] This adaptability relies on the software's awareness of the user interface state to resolve ambiguities and optimize relevance.[29]Representation

Notation Conventions

Notation conventions for keyboard shortcuts standardize their representation in documentation, user interfaces, and technical writing to ensure clarity and consistency across platforms. The most widely adopted symbolic standard uses the plus sign (+) to denote simultaneous key combinations, such as Ctrl+Alt+Del on Windows systems.[26] This convention originated in early graphical user interfaces and has been formalized in style guides by major operating system developers. Platform-specific modifiers further differentiate notations; for instance, Windows documentation typically employs Ctrl for the Control key, while macOS uses Cmd (or the Command symbol ⌘) to distinguish it from the Windows Ctrl.[10][26] Typographic rules enhance readability by applying specific formatting to key names. Key labels are often rendered in bold or monospace font to distinguish them from surrounding text, with combinations separated by hyphens or plus signs for sequential or simultaneous presses, respectively (e.g., Ctrl + C or Ctrl-C).[26] In international contexts, symbolic icons replace textual labels where possible; Apple's documentation, for example, uses the ⌘ symbol for the Command key, ⌥ for Option, and ⇧ for Shift, reflecting localized keyboard ergonomics and reducing translation needs.[10] These practices align with broader accessibility guidelines, ensuring shortcuts are visually parseable in diverse linguistic environments. Historically, notation standards have evolved alongside keyboard technology. The ISO/IEC 9995 series, particularly Part 7, standardizes graphical symbols for function keys such as Escape (⎋), Alt, and Insert, influencing how these elements are depicted in global documentation and keycaps.[32] Earlier representations drew from ASCII control character conventions in computing manuals from the 1970s and 1980s, where unprintable controls were denoted using caret notation (e.g., ^C for Ctrl+C), a method still referenced in Unix-like system documentation for its compactness in terminal outputs.[33] This progression from textual ASCII encodings to symbolic and typographic systems reflects the shift from command-line interfaces to modern graphical applications.Examples in Practice

Keyboard shortcuts are widely used in computing to perform common actions efficiently. The concepts of cut, copy, paste, and undo originated in the 1970s at Xerox PARC, where computer scientist Larry Tesler developed them as part of modeless text editing in the Gypsy word processor, eliminating the need for modal commands and enabling seamless interaction across applications.[34] The specific shortcuts ⌘+X (cut), ⌘+C (copy), ⌘+V (paste), and ⌘+Z (undo) were first implemented in the Apple Lisa in 1983; equivalents using Ctrl became standard in Windows from 1992.[5] They have since become cross-platform standards, adopted in operating systems like Windows, macOS, and Linux, as well as in numerous software programs, due to their intuitive mapping to editing workflows inspired by physical cut-and-paste methods.[15] Modifier keys, such as Ctrl, Alt, and Shift, combine with letter or function keys to create more specialized shortcuts. For instance, Alt+F4 closes the active window or application, a convention that allows quick termination of tasks without navigating menus. This shortcut stems from the 1987 IBM Common User Access (CUA) guidelines, which standardized interface behaviors to promote consistency across systems; F4 was selected for "close" as it followed other function key assignments like F9 for minimize.[35] Similarly, on macOS, Cmd+Space activates the Spotlight search feature, enabling rapid access to files, apps, and system functions. Introduced as the default in macOS Tiger in 2005, it leverages the Command key (formerly Apple key) as a primary modifier for macOS-specific actions, illustrating how platforms adapt universal modifier principles to their ecosystems.[36] Beyond these, simpler single-key shortcuts handle routine interactions in user interfaces. The Esc key, short for "escape," is commonly used to cancel ongoing operations, close dialogs, or exit menus, providing an immediate way to abort without commitment. Its role as a cancel function evolved from its 1960 invention by programmer Bob Bemer, who introduced it to signal code switches in early computing, later standardized for interruption in terminal and GUI contexts.[37] Likewise, the Tab key facilitates navigation between form fields or interactive elements, moving focus forward in a logical sequence to streamline data entry. Derived from its function on typewriters for tabulation, which dates back to the early 20th century with patents from 1903, it became a navigation standard in graphical interfaces, supporting efficient keyboard-only workflows in forms and dialogs. These examples highlight how shortcuts, often using standard notations like Ctrl or Cmd, integrate modifier and single keys to enhance usability across diverse computing scenarios.Modification

Customization Options

Users can customize keyboard shortcuts through built-in operating system tools that allow remapping of keys and assignment of new combinations to system functions. In Windows, the PowerToys Keyboard Manager enables users to remap single keys or entire shortcuts, supporting features like remapping the Caps Lock key to Ctrl or creating custom mappings for applications.[38] On macOS, the System Settings Keyboard Shortcuts pane provides options to add, edit, or remove shortcuts for apps and system features, such as assigning a custom combination to launch Mission Control.[39] On Linux distributions, tools like xmodmap or desktop environment settings (e.g., GNOME Tweaks) enable key remapping, often requiring configuration files for advanced rules.[40] Application-specific customization is common in professional software, where users access dedicated menus to tailor shortcuts to workflows. For instance, in Adobe Photoshop, the Keyboard Shortcuts dialog allows selection of commands from menus like File or Edit and assignment of new key combinations, with options to save custom sets for export.[41] Similar interfaces exist in other Adobe applications, such as Premiere Pro, where users can resolve conflicts by reassigning keys and duplicating default shortcut files for modification.[42] Third-party software extends customization capabilities beyond native tools, offering scripting for advanced remapping and conditional logic. AutoHotkey on Windows uses simple scripts to remap keys, such as converting a key press into a sequence of actions or context-sensitive hotkeys based on active windows.[43] For macOS, Karabiner-Elements supports complex modifications, including changing keys to other keys, adding virtual keys, or applying rules that vary by application or device.[44] The process of customizing shortcuts typically involves selecting a target command or function, assigning a desired key combination, and checking for conflicts to ensure functionality. This user-driven approach has empowered productivity enhancements since the widespread adoption of graphical user interfaces in the 1990s, allowing personalization without altering core software code.[45] Conflicts may arise with reserved shortcuts, which remain immutable to maintain system stability.Reserved Shortcuts

Reserved shortcuts are predefined key combinations in operating systems and applications that users cannot modify or reassign, ensuring reliable access to essential system functions. These shortcuts are typically hard-coded at a low level of the operating system to prevent interference from user applications or custom configurations. In Windows, for instance, the Ctrl+Alt+Del combination invokes the security screen, providing options such as Task Manager for ending unresponsive processes, locking the workstation, or signing out, which is crucial for system recovery during hangs or crashes.[46] Similarly, in macOS, Command+Option+Esc opens the Force Quit Applications dialog, allowing users to terminate frozen apps without rebooting the entire system.[10] The rationale for reserving these shortcuts lies in their role as fail-safes for critical operations, guaranteeing availability even when higher-level software fails or becomes unresponsive. Customization is blocked to avoid scenarios where remapping could render these functions inaccessible during emergencies, such as application locks or security threats; this enforcement occurs through kernel-level handling, where the operating system intercepts the key sequence before it reaches user-space applications.[38] In Windows, Ctrl+Alt+Del functions as a Secure Attention Key, processed directly by the kernel to maintain integrity against potential malware interception.[47] For macOS, system-reserved shortcuts like Command+Option+Esc are similarly protected, requiring third-party tools for any override, which underscores their priority for stability.[48] More recently, as of 2023, the Copilot key on compatible Windows keyboards is handled at the firmware level, making full remapping challenging without specialized tools.[49] Cross-platform patterns emerge in hardware-level reservations, such as power button presses or BIOS/UEFI access keys, which trigger interrupts independent of the OS. The Delete key (or F2/F10 variants) for entering BIOS setup during boot, for example, relies on firmware interrupts established in early PC architectures. These conventions, while rooted in early PC interrupt handling, became standardized in the mid-1980s with CMOS-based BIOS setups in systems like the IBM PC/AT and compatible clones, often using the Delete key for entry in AMI and Award BIOS implementations.[50] Power key handling in modern systems often uses ACPI interrupts (introduced in 1996) for safe shutdowns or suspensions, building on low-level interrupt protections established in early PC architectures.[51]Applications

Operating Systems

In Microsoft Windows, keyboard shortcuts are deeply integrated into the operating system's core functionality, enabling quick access to system tools and features. For instance, the Windows key combined with R (Win+R) opens the Run dialog box, allowing users to directly execute commands or launch applications without navigating menus. Another example is pressing Alt + F4 with the desktop focused (no active window) to open the shutdown dialog, from which users can select "Switch user" from the dropdown menu and press Enter to switch to another user account.[52][53] These native shortcuts extend to shell extensions, where third-party integrations can register custom hotkeys that interact with the Windows shell for tasks like file operations or system utilities. The evolution of Windows keyboard shortcuts traces back to MS-DOS, where control key sequences such as Ctrl+C for interrupting processes laid the groundwork for modern modifier-based combinations, preserving compatibility through features like Alt+numeric keypad sequences for character input.[54][55][56][57] Apple's macOS emphasizes the Command key (⌘) as the primary modifier for system-wide shortcuts, promoting efficient navigation within its graphical user interface. A representative example is Cmd+C, which copies the selected item to the Clipboard, a standard action consistent across Finder and applications. This design was formalized in the Aqua interface standards introduced with Mac OS X in 2001, which reserve key combinations like Cmd+Z for undo, Cmd+X for cut, and Cmd+V for paste to ensure uniformity and developer adherence in Cocoa-based apps. macOS's Unix heritage, rooted in the Darwin kernel derived from BSD, influences these shortcuts by incorporating command-line compatible behaviors, such as Option key modifications for alternative actions, while maintaining a user-friendly layer over the underlying POSIX-compliant system.[10][58][59] Linux distributions exhibit significant variability in keyboard shortcut implementation due to the diversity of desktop environments (DEs), with underlying display servers like X11 and Wayland handling input events differently. In GNOME, the Super key (often the Windows key) activates the Activities overview, providing an instant search and app launcher interface, while additional shortcuts like Super+Tab switch between windows. KDE Plasma, in contrast, offers extensive customization through its settings panel, where users can assign global shortcuts such as Meta (Super) for the application menu or Alt+F2 for the command runner, allowing profiles for different workflows. Event handling in X11 involves the kernel mapping hardware scancodes to keycodes (incremented by 8 for Xorg compatibility), enabling DEs to interpret and route inputs via libraries like Xlib, whereas Wayland delegates keyboard events directly to compositors through protocols like wl_keyboard, improving security by isolating client access and reducing global keylogging risks.[60][61][24]Software Applications

In web browsers, keyboard shortcuts facilitate efficient navigation and management of browsing sessions. For instance, the combination Ctrl+T opens a new tab in Google Chrome, allowing users to quickly expand their browsing context without interrupting the current page.[62] Similarly, Mozilla Firefox employs Ctrl+T to create a new tab, a practice shared across major browsers to enhance user familiarity and cross-application consistency in tabbed interface operations.[63] Office suites rely on keyboard shortcuts to streamline text formatting and document manipulation, drawing from longstanding conventions in word processing. In Microsoft Word, Ctrl+B toggles bold formatting on selected text, enabling rapid emphasis without menu navigation.[64] LibreOffice Writer adopts the same Ctrl+B shortcut for bold, reflecting inherited standards from early 1980s word processors like WordStar, where such bindings first popularized mnemonic controls for formatting tasks.[65][66] These shortcuts prioritize intuitive letter associations—B for bold—to boost productivity in document creation and editing workflows. Development tools, particularly integrated development environments (IDEs), incorporate keyboard shortcuts to accelerate coding and debugging processes. In Visual Studio Code, Ctrl+Space triggers IntelliSense for autocomplete suggestions, providing context-aware code completions to reduce typing errors and speed up development. This IDE further supports extensible key bindings through its settings and plugins, allowing developers to remap or add shortcuts via JSON configuration files or extensions from the marketplace, tailoring interactions to individual workflows.[67]Implications

Benefits

Keyboard shortcuts enhance user efficiency by enabling faster command execution compared to graphical alternatives like menus or icons. In a study of experienced Microsoft Word users performing common tasks, keyboard shortcuts took an average of 1.36 to 1.51 seconds per command, compared to 2.02 to 2.17 seconds for icon toolbars and 2.71 to 3.13 seconds for pull-down menus, representing time savings of approximately 30-50% for repetitive operations when transitioning from mouse-based interactions.[68] Research indicates that proficient shortcut users exhibit faster interaction times across non-typing tasks, potentially decreasing cumulative physical stress from prolonged device switching.[69] Human-computer interaction guidelines, such as those established by the Nielsen Norman Group in the 1990s, emphasize accelerators like shortcuts to promote efficient workflows that accommodate expert users.[70] For power users in fields like coding and graphic design, keyboard shortcuts yield substantial productivity gains through seamless navigation and command invocation without visual searching. Studies on shortcut adoption show that experienced developers and designers report significant workflow accelerations, as hands remain on the keyboard to avoid context switches that disrupt flow.[69] Additionally, these shortcuts improve accessibility for visually impaired users by integrating directly with screen readers, enabling efficient content navigation via key sequences that bypass mouse dependency.[71]Limitations and Accessibility

Keyboard shortcuts often impose a significant learning curve on users, particularly novices who face memorization overload from numerous non-intuitive combinations. Research indicates that shortcut efficiency improves only after repeated practice, with users requiring approximately 200 repetitions for shortcuts to outperform graphical user interfaces in speed and ease of retrieval. A survey of Japanese university students revealed that 20% were unaware of any keyboard shortcuts, while 40% did not know basic copy-paste combinations like Ctrl+C and Ctrl+V, highlighting retention challenges among beginners.[72][73] Physical barriers further limit accessibility for users with motor impairments, who may struggle with simultaneous multi-key presses required by many shortcuts. To mitigate this, accessibility features such as Sticky Keys—allowing users to press and release keys sequentially rather than simultaneously—were introduced in Windows 95 as part of Microsoft's early efforts to support disabled users. Similar adaptations, like Filter Keys for debouncing repeated presses, have since become standard in operating systems to reduce strain from conditions such as repetitive strain injury or tremors.[74] Compatibility issues pose additional challenges, particularly in multilingual keyboard layouts where shortcuts designed for standard QWERTY configurations fail to align with alternative key mappings, such as AZERTY or non-Latin scripts. In virtual machine environments, shortcuts can conflict between host and guest systems, intercepting inputs unexpectedly and disrupting workflows. For web applications, these barriers are addressed by the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.2, released in 2023, which mandate full keyboard operability without traps or exceptions to ensure equitable access across diverse setups.[75]References

- https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/apps/design/[accessibility](/page/Accessibility)/keyboard-accessibility