Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Window (computing)

View on WikipediaIn computing, a window is a graphical control element. It consists of a visual area containing some of the graphical user interface of the program it belongs to and is framed by a window decoration. It usually has a rectangular shape[1] that can overlap with the area of other windows. It displays the output of and may allow input to one or more processes.

Windows are primarily associated with graphical displays, where they can be manipulated with a pointer by employing some kind of pointing device. Text-only displays can also support windowing, as a way to maintain multiple independent display areas, such as multiple buffers in Emacs. Text windows are usually controlled by keyboard, though some also respond to the mouse.

A graphical user interface (GUI) using windows as one of its main "metaphors" is called a windowing system, whose main components are the display server and the window manager.

History

[edit]

The idea was developed at the Stanford Research Institute (led by Douglas Engelbart).[2] Their earliest systems supported multiple windows, but there was no obvious way to indicate boundaries between them (such as window borders, title bars, etc.).[3]

Research continued at Xerox Corporation's Palo Alto Research Center / PARC (led by Alan Kay). They used overlapping windows.[4]

During the 1980s the term "WIMP", which stands for window, icon, menu, pointer, was coined at PARC.[citation needed]

Apple had worked with PARC briefly at that time. Apple developed an interface based on PARC's interface. It was first used on Apple's Lisa and later Macintosh computers.[5] Microsoft was developing Office applications for the Mac at that time. Some speculate that this gave them access to Apple's OS before it was released and thus influenced the design of the windowing system in what would eventually be called Microsoft Windows.[6]

Properties

[edit]Windows are two dimensional objects arranged on a plane called the desktop metaphor. In a modern full-featured windowing system they can be resized, moved, hidden, restored or closed.

Windows usually include other graphical objects, possibly including a menu-bar, toolbars, controls, icons and often a working area. In the working area, the document, image, folder contents or other main object is displayed. Around the working area, within the bounding window, there may be other smaller window areas, sometimes called panes or panels, showing relevant information or options. The working area of a single document interface holds only one main object. "Child windows" in multiple document interfaces, and tabs for example in many web browsers, can make several similar documents or main objects available within a single main application window. Some windows in macOS have a feature called a drawer, which is a pane that slides out the side of the window and to show extra options.

Applications that can run either under a graphical user interface or in a text user interface may use different terminology. GNU Emacs uses the term "window" to refer to an area within its display while a traditional window, such as controlled by an X11 window manager, is called a "frame".

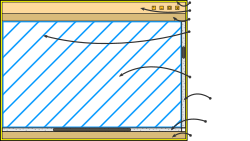

Any window can be split into the window decoration and the window's content, although some systems purposely eschew window decoration as a form of minimalism.

Window decoration

[edit]

The window decoration is a part of a window in most windowing systems.

Window decoration typically consists of a title bar, usually along the top of each window and a minimal border around the other three sides.[7] On Microsoft Windows this is called "non-client area".[8]

In the predominant layout for modern window decorations, the top bar contains the title of that window and buttons which perform windowing-related actions such as:

- Close

- Maximize

- Minimize

- Resize

- Roll-up

The border exists primarily to allow the user to resize the window, but also to create a visual separation between the window's contents and the rest of the desktop environment.

Window decorations are considered important for the design of the look and feel of an operating system and some systems allow for customization of the colors, styles and animation effects used.

Window border

[edit]

Window border is a window decoration component provided by some window managers, that appears around the active window. Some window managers may also display a border around background windows. Typically window borders enable the window to be resized or moved by dragging the border. Some window managers provide useless borders which are purely for decorative purposes and offer no window motion facility. These window managers do not allow windows to be resized by using a drag action on the border.

Title bar

[edit]

The title bar is a graphical control element and part of the window decoration provided by some window managers. As a convention, it is located at the top of the window as a horizontal bar. The title bar is typically used to display the name of the application or the name of the open document, and may provide title bar buttons for minimizing, maximizing, closing or rolling up of application windows. These functions are typically placed in the top-right of the screen to allow fast and inaccurate inputs through barrier pointing. Typically title bars can be used to provide window motion enabling the window to be moved around the screen by grabbing the title bar and dragging it. Some window managers[which?] provide title bars which are purely for decorative purposes and offer no window motion facility. These window managers do not allow windows to be moved around the screen by using a drag action on the title bar.

Default title-bar text often incorporates the name of the application and/or of its developer. The name of the host running the application also appears frequently. Various methods (menu-selections, escape sequences, setup parameters, command-line options – depending on the computing environment) may exist to give the end-user some control of title-bar text. Document-oriented applications like a text editor may display the filename or path of the document being edited. Most web browsers will render the contents of the HTML element title in their title bar, sometimes pre- or postfixed by the application name. Google Chrome and some versions of Mozilla Firefox place their tabs in the title bar. This makes it unnecessary to use the main window for the tabs, but usually results in the title becoming truncated. An asterisk at its beginning may be used to signify unsaved changes.

The title bar often contains widgets for system commands relating to the window, such as a maximize, minimize, rollup and close buttons; and may include other content such as an application icon, a clock, etc.

Title bar buttons

[edit]Some window managers provide title bar buttons which provide the facility to minimize, maximize, roll-up or close application windows. Some window managers may display the title bar buttons in the task bar or task panel, rather than in the title bars.

The following buttons may appear in the title bar:

- Close

- Maximize

- Minimize

- Resize

- Roll-up (or WindowShade)

Note that a context menu may be available from some title bar buttons or by right-clicking.

Title bar icon

[edit]Some window managers display a small icon in the title bar that may vary according to the application on which it appears. The title bar icon may behave like a menu button, or may provide a context menu facility. macOS applications commonly have a proxy icon next to the window title that functions the same as the document's icon in the file manager.

Document status icon

[edit]Some window managers display an icon or symbol to indicate that the contents of the window have not been saved or confirmed in some way: macOS displays a dot in the center of its close button; RISC OS appends an asterisk to the title.

Tiling window managers

[edit]Some tiling window managers provide title bars which are purely for informative purposes and offer no controls or menus. These window managers do not allow windows to be moved around the screen by using a drag action on the title bar and may also serve the purpose of a status line from stacking window managers.

In popular operating systems

[edit]| OS | Icon | Send to Back | Close | Maximize | Menu bar | Minimize | Pin (Keep on top) | Resize | Roll-up (Window shade) | Status | Context menu | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unix-like with X11 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Many X window managers for Unix-like systems allow customization of the type and placement of buttons shown in the title bar. |

| macOS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Buttons are on the left side of the title bar. Icon is a proxy for the document's filesystem representation. | |||||

| RISC OS | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||

| Windows | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Icon is menu of window actions |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Reimer, Jeremy (2005). "A History of the GUI (Part 3)". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 2009-09-08. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ^ Reimer, Jeremy (2005). "A History of the GUI (Part 1)". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 2009-09-18. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ^ Reimer, Jeremy (2005). "A History of the GUI (Part 2)". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 2009-09-08. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ^ "PARC History - A Legacy Of Innovation And Inventing The Future". Palo Alto Research Center Incorporated. 19 October 2023. Archived from the original on 3 December 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

Xerox PARC debuts the first GUI, which uses icons, pop-up menus, and overlapping windows that can be controlled easily using a point-and-click technique.

- ^ Reimer, Jeremy (2005). "A History of the GUI (Part 4)". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 2009-09-08. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ^ Reimer, Jeremy (2005). "A History of the GUI (Part 5)". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 2009-09-07. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- ^ "Unknown".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Nonclient Area - Win32 apps". Archived from the original on 2024-06-03. Retrieved 2024-06-03.

Window (computing)

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Purpose

In computing, a window is defined as a rectangular area on a display screen that serves as a primary visual interface for a software application or operating system component, containing graphical elements such as text, images, or controls.[1] This area is typically movable by dragging and resizable by adjusting its borders, allowing users to position and scale it according to their needs.[1] As a fundamental element of graphical user interfaces (GUIs), a window encapsulates the output and input handling for its associated application, processing events like mouse clicks or keystrokes through a dedicated procedure.[1] The primary purposes of a window include isolating the content of a specific application from others on the screen, which facilitates multitasking by enabling multiple windows to coexist and overlap without interference.[1] This isolation ensures that each application's visual and interactive elements remain self-contained, reducing visual clutter and allowing users to switch focus between tasks efficiently.[1] Additionally, windows provide user control over visibility and focus, such as minimizing to an icon, maximizing to full screen, or bringing a window to the foreground, thereby enhancing usability in multi-application environments.[1] Terminology for top-level containers varies across GUI frameworks; for example, in Java Swing, "frames" refer to top-level windows managed by the operating system, while "panels" are embedded components for organizing controls within such containers. In general, windows function as top-level elements in windowing systems, directly managed by the operating system and not nested inside another window.[10] The concept of windows emerged during the shift from command-line to graphical interfaces in the 1970s and 1980s, laying the groundwork for modern desktop computing.[11]Basic Components

A window in computing consists of several essential structural components that form its core anatomy, enabling the display and interaction with application content. The primary element is the client area, which is the inner region of the window dedicated to rendering application-specific output, such as text, graphics, or user interface elements, excluding any surrounding frame or decorations.[1] This area is managed by the application's window procedure, which processes input events and updates the display accordingly.[1] Often referred to interchangeably as the content area in some contexts, it serves as the bounded space where the core functionality of the software is visualized.[1] The client area represents the visible portion of the potentially larger content, particularly in cases involving scrolling or panning mechanisms. It is defined in device-specific coordinates and acts as a rectangular region mapped to the display, allowing users to view subsets of extensive data without altering the underlying content structure.[12] For instance, in document viewers, the client area determines the on-screen slice of a multi-page file, with scroll bars facilitating navigation beyond its boundaries.[13] These components are integral to windowing systems, where windows function as managed entities identified by unique handles or IDs for programmatic access and control. In the X11 protocol, each window is assigned a 32-bit Window ID upon creation, serving as a handle for operations like resizing or event handling by the X server.[14] Similarly, in Wayland, windows are represented as surfaces with identifiers like struct wl_surface, enabling direct communication between clients and the compositor for buffer management and rendering.[15] On Windows platforms, the handle (HWND) is returned during window creation and used for system API calls, such as retrieving the desktop window or manipulating child windows.[1] This handle-based approach allows the windowing system to oversee layout, input routing, and resource allocation while isolating application logic to the client area. Examples of minimal windows highlight the variability in implementation across environments. In embedded systems, windows often consist of basic client areas rendered directly to a framebuffer without complex management, using lightweight libraries like LVGL to draw simple primitives and text in resource-constrained devices such as microcontrollers. These bare windows prioritize efficiency, focusing solely on essential content display for applications like control panels on IoT hardware. In contrast, full-featured desktop environments, such as those in X11 or Windows, incorporate richer client areas within hierarchical window structures, supporting layered compositions for multitasking interfaces.[14][1] The modularity afforded by these components—separating the client area from system-level management—underpins GUI design principles, allowing developers to encapsulate application content independently of display hardware or orchestration details. This separation facilitates portability and scalability in software development, as applications can render to the client area agnostic of the underlying windowing protocol.[16][15]Historical Development

Early Concepts

The early concepts of windows in computing emerged from theoretical explorations of interactive systems aimed at augmenting human capabilities through visual and spatial organization of information. In his 1962 report "Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework," Douglas Engelbart outlined the need for computer-driven displays to support real-time manipulation of symbolic structures, emphasizing spatial arrangements such as dividing the screen into regions—like the left two-thirds for primary content and the right third for supplementary views—to enhance comprehension of complex problems.[17] This framework highlighted bitmapped or graphical displays as essential for flexible, non-serial presentation of data, foreshadowing windowing as a means to organize interactive computing environments.[17] Pioneering implementations in the 1960s built on these ideas with experimental systems using cathode-ray tube (CRT) displays. Ivan Sutherland's 1963 Sketchpad system, developed on the TX-2 computer, introduced interactive graphical communication via a light pen, featuring an adjustable "scope window" that allowed users to magnify and pan across portions of a larger virtual page up to 2000 times, enabling focused views of drawings while maintaining topological connections between elements.[18] Sutherland's vector-based display supported dynamic updates but operated on a single visible region at a time. Building directly on Engelbart's vision, the oN-Line System (NLS), demonstrated in 1968 at the Fall Joint Computer Conference, advanced this by displaying multiple overlapping windows on a raster CRT for hierarchical document navigation, hypertext linking, and collaborative editing, such as inset video windows for remote interaction.[19] The Xerox Alto, operational from 1973 at Xerox PARC, represented the first practical experiment in bitmapped windowing for everyday tasks like document viewing. Its 1024×879 pixel display used bit-block transfer (BitBlt) operations to render graphics efficiently, with applications like the Bravo editor employing display control blocks to divide the screen into horizontal strips for multi-font text and image handling, functioning as proto-windows for WYSIWYG editing.[20] These strips allowed segmented views, and the system supported overlapping windows through efficient BitBlt operations.[21] Early window designs were profoundly shaped by hardware constraints, including low-resolution displays (often effectively below 1024×1024 pixels) and exorbitant memory costs—such as $15,000 for a 16,000-word module in the early 1970s—which restricted systems to simple, non-overlapping regions or vector refreshes rather than complex, dynamic multi-window interfaces.[22] Vector CRTs like those in Sketchpad prioritized line drawing over filled areas, while nascent raster systems in NLS and Alto contended with high refresh bandwidths and limited core memory, forcing designers to favor minimalistic spatial divisions for feasible real-time interaction.[23]Evolution in Graphical Interfaces

The evolution of windows in graphical user interfaces began in the 1980s with key commercial milestones that transitioned experimental concepts into practical systems. The Xerox Star, released in 1981 by Xerox PARC, marked the first commercial implementation of a window-based graphical user interface, featuring overlapping, resizable windows on a bitmapped display to enable intuitive document manipulation.[24] This was followed by Apple's Lisa in 1983, which introduced overlapping windows as a core element of its GUI, allowing users to manage multiple applications simultaneously on screen.[25] The Apple Macintosh in 1984 further popularized these overlapping windows in a more affordable personal computer, making windowed interfaces accessible to a broader audience and influencing subsequent designs.[26] In the 1990s, standardization efforts solidified windows as a fundamental aspect of operating systems. Microsoft Windows 1.0, launched on November 20, 1985, provided an initial graphical shell over MS-DOS with support for tiled and overlapping windows, though limited by hardware constraints.[27] By Windows 3.0 in 1990, enhancements included improved tiling for non-overlapping arrangements and iconification to minimize windows, boosting usability and contributing to widespread adoption.[28] Concurrently, the X Window System, first released in 1984 by MIT, became the de facto standard for Unix-like environments, enabling portable window management across diverse hardware and fostering networked graphical applications.[29] From the 2000s to the 2020s, windows evolved through deeper integration with emerging technologies and platforms. Web technologies increasingly blurred lines between browser and desktop windows, exemplified by frameworks like Electron (introduced in 2013), which allow developers to create cross-platform desktop applications using HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, rendering them as native-like windows.[30] Mobile adaptations advanced window concepts, such as Apple's introduction of Split View multitasking in iOS 9 (2015), enabling side-by-side app windows on iPad for enhanced productivity.[31] Open-source projects like GNOME (initiated in 1997) and KDE (founded in 1996) contributed significantly to window management in Linux, iterating on X11 and later Wayland protocols for more efficient, customizable interfaces.[32] In the 2020s, the Wayland protocol saw increasing adoption as the default in major Linux distributions, offering improved performance, security, and smoother window compositing compared to X11.[33] Microsoft enhanced window management with Snap Layouts in Windows 11 (released October 2021), providing predefined arrangements for multitasking across multiple monitors.[34] Advancements in hardware profoundly shaped window design, particularly the shift from monochrome displays in early systems like the Xerox Star to color and eventually high-DPI screens. This progression necessitated scalable window rendering to maintain clarity and responsiveness; for instance, the introduction of high-resolution displays in the 2010s, such as Apple's Retina in 2012, drove UI frameworks to adopt vector graphics and adaptive scaling, ensuring windows remained legible and performant across resolutions.[24]Core Properties

Dimensions and Positioning

In graphical user interfaces (GUIs), the dimensions of a window are primarily defined by its width and height, measured in device units that typically correspond to pixels on the display. These dimensions determine the rectangular area occupied by the window, excluding decorations like borders and title bars, and are specified in client coordinates relative to the window's interior. To accommodate high-DPI displays, modern systems employ DPI awareness modes, where dimensions can be expressed in logical pixels (device-independent pixels, or DIPs) that scale based on the display's dot-per-inch setting, ensuring consistent sizing across varying hardware resolutions. For example, Windows uses DPI awareness levels. Aspect ratios, representing the proportional relationship between width and height, are not inherently enforced by core windowing systems but can be maintained programmatically by applications handling resize events to preserve usability in content like images or videos. To prevent usability issues such as content becoming unreadable or controls overlapping, windows often include minimum and maximum size constraints. For example, in Windows, these are managed through structures like MINMAXINFO, which applications populate in response to the WM_GETMINMAXINFO message to specify the smallest allowable tracking size (e.g., derived from system metrics like SM_CXMINTRACK, typically around 150-250 pixels depending on system and DPI as of 2025) and the largest (often limited by the virtual screen extent). Similar constraints are set in macOS via NSWindow minSize/maxSize properties. A minimum size might ensure a window remains large enough to accommodate essential UI elements, while maximum sizes align with monitor capabilities to avoid excessive resource use. Window positioning establishes the location of this rectangular area on the screen, typically using absolute coordinates (x, y) with the origin at the upper-left corner of the primary display. These coordinates are in screen pixels, allowing precise placement; for example, in Windows via SetWindowPos, which accepts x and y values to reposition a window while optionally preserving its size or Z-order; in macOS via NSWindow's setFrame:. Relative placement strategies, like cascading, offset new windows slightly from existing ones (e.g., by 20-30 pixels diagonally in many systems) to make title bars visible without overlap; this can be achieved programmatically, such as using CascadeWindows in Windows. Overlapping windows are managed through Z-order (or stacking order), a hierarchy along an imaginary z-axis perpendicular to the screen, determining visibility and input focus. The topmost window appears in front, with owned windows always above their owners and child windows grouped with parents. For example, in Windows, this is set via HWND_TOP in SetWindowPos; equivalents exist in macOS (orderFront:) and Linux (XRaiseWindow in X11). Foreground windows, associated with the active thread or process, receive user input and sit at the top of their Z-order group, while background windows remain lower in the stack; functions like SetForegroundWindow in Windows adjust this to bring a window forward. Positioning is subject to various constraints to ensure windows remain functional and visible. Windows cannot extend beyond screen boundaries, defined by the virtual screen encompassing all monitors, with APIs automatically clipping or adjusting placements that would otherwise fall outside. In multi-monitor setups, positioning accounts for the contiguous virtual desktop, restricting windows to individual monitor work areas excluding taskbars or docks. User-initiated snapping to edges constrains dragging to predefined layouts like half-screen or quarter-screen positions for efficient multi-window arrangements; for example, introduced as Aero Snap in Windows 7 and evolved into Snap layouts in Windows 11 as of 2025. Operating systems enforce multi-window layout policies, such as Snap Assist (now part of Snap layouts) in Windows, which suggests complementary placements to optimize screen real estate without manual adjustment. Similar features exist in macOS (Split View) and GNOME (tiling).States and Behaviors

Windows in graphical user interfaces operate in several core states that determine their visibility, size, and interaction level. The normal or restored state positions the window at its default or previously set dimensions and location on the screen, allowing full visibility and user interaction. In the maximized state (or zoomed/full-screen), the window expands to occupy the entire screen or its parent container's client area, optimizing space for content display while retaining access to system controls. The minimized state reduces the window to an icon or entry in the taskbar or dock, hiding its content but preserving its session for quick restoration. Additionally, windows can enter a hidden state, where they are not rendered on the display despite remaining in memory, often used for background processes or temporary concealment. Behavioral responses enable dynamic user control over windows. Resizing typically occurs by dragging the window's borders or corners (or via gestures on touch devices), provided the window style supports resizable frames, which adjusts its dimensions in real-time. Moving a window involves dragging its title bar (or frame) to reposition it within the desktop bounds, updating its coordinates relative to the screen. Closing is initiated via a dedicated button in the title bar, the Escape key in some contexts, or keyboard shortcuts like Alt+F4 (Windows) or Cmd+W (macOS), which terminates the window and releases its resources. Keyboard shortcuts like Alt+Tab (Windows/Linux) or Cmd+Tab (macOS) facilitate switching between windows, cycling through open instances to activate the selected one. Focus and activation distinguish the currently interactive window from others. An active (or key) window, positioned at the top of the z-order, receives primary user input and features visual cues such as a highlighted title bar to indicate its status. For example, in macOS, the Key window accepts input while Main windows are frontmost but inactive. Inactive windows, while visible, do not process keyboard or mouse events directed to them, preventing unintended interactions. Event handling routes mouse and keyboard inputs exclusively to the focused window or its child elements, ensuring precise control; for instance, keystrokes are queued to the process owning the focused window until focus shifts. To maintain visual consistency, windows handle error states through invalidation and repainting mechanisms. When content changes—such as updates to text, graphics, or layout—the affected region is invalidated, triggering a repaint that prompts the application to redraw the window's client area. For example, in Windows via WM_PAINT and UpdateWindow; similar in other systems. This process ensures the display reflects the current state without artifacts, with the system coalescing multiple invalidations into a single repaint cycle for efficiency.[35][36][37][38][39][35][40][41][39][40][42][43][44][45][39][39][39][39][46][46][39][39][47][48][48][49][50]Window Decorations

Borders and Frames

In graphical user interfaces (GUIs), borders and frames form the outer structural elements that delineate a window's boundaries, providing visual separation from the desktop or other windows while facilitating user interaction. The frame typically encloses the entire window, encompassing both the client area (where content is displayed) and non-client areas (such as edges used for manipulation), as defined in systems like the X Window System where windows have a configurable border width of zero or more pixels surrounding the interior.[51] In Microsoft Windows, the frame is managed by the Desktop Window Manager (DWM), which handles rendering of these elements, including extensions into the client area for custom designs.[52] Similarly, in macOS Cocoa, the NSWindow class uses a frame rectangle to bound the window, with borders drawn by underlying views to contain content and enable event handling.[53] Border types vary across platforms to enhance visual distinction and usability, often featuring solid lines, drop shadows, or subtle rounded corners. In the X Window System, borders can be rendered as solid colors via the border-pixel attribute or as patterns using pixmaps that match the window's depth, allowing for flexible visual styles while ensuring graphics are clipped to the interior.[54] Windows DWM supports drop shadows and glass-like effects for borders, particularly in Aero themes, to create depth without jagged edges, though custom implementations may remove standard borders entirely.[55] Thickness typically ranges from 1 to 5 pixels to balance aesthetics and functionality, with wider margins (e.g., 8 pixels on sides and 20-27 pixels on bottom/top in Windows custom frames) serving as grip areas for resizing.[56] Rounded corners, when present, contribute to modern appearances, as seen in macOS where window corners include interactive elements like resizing indicators without altering the overall frame structure.[53] Frames distinguish between resizable and fixed configurations to suit different window purposes; resizable frames include draggable edges, while fixed ones, such as those for dialog boxes, use thin, non-draggable borders to prevent alteration. In Windows, resizable frames rely on non-client area calculations via WM_NCCALCSIZE to define boundaries, whereas fixed dialogs minimize border interactivity.[55] macOS implements this through NSWindow styles, where resizable variants add a lower-right resizing triangle within the frame border.[53] Functionally, borders act as hit-test regions to detect user intentions, such as resizing operations—triggering cursor changes to arrows when hovering over edges—or moving the window, processed through mechanisms like WM_NCHITTEST in Windows or event distribution in Cocoa.[57] Modern rendering employs anti-aliasing to smooth these edges, reducing pixelation in composited environments like DWM, where subpixel rendering blends border pixels for cleaner visuals during scaling or overlap.[58] Variations include frameless windows, common in web applications, where native OS frames are omitted to allow custom styling; for instance, Electron apps set frame to false, relying on CSS properties like border: none to remove visible boundaries and integrate seamlessly with web content.[59] This contrasts with native OS frames in desktop environments, which enforce standard borders for consistency and accessibility, though developers can override them for specialized interfaces.[52]Title Bars and Controls

The title bar is the horizontal region at the top of a graphical user interface (GUI) window, serving as the primary area for displaying the window's title text, which typically includes the application name and, if applicable, the name of the open document or file being edited.[60] This text enables users to quickly identify and distinguish between multiple open windows.[61] The title bar's background color often varies to indicate the window's active status: active windows generally feature a vibrant accent color for prominence, while inactive windows use a subdued tone, such as a muted gray, to de-emphasize them and reduce visual clutter.[62] Standard control buttons embedded in the title bar provide essential window management functions, including minimize (to send the window to the taskbar or dock), maximize/restore (to expand the window to full screen or return it to its previous size), and close (to exit the application or window).[63] These buttons are positioned on the right side in Windows operating systems and on the left side in macOS, reflecting platform-specific design conventions.[64] Applications may incorporate custom buttons within the title bar for additional functionality, such as a help icon to access documentation or support features, allowing developers to extend the standard set while maintaining integration with the OS theme.[62] The title bar functions as the main interactive handle for repositioning windows; users can click and drag it to move the window across the screen without altering its size or content.[65] In many GUI systems, double-clicking the title bar toggles the window between its normal and maximized states, streamlining resizing operations—though the exact behavior, such as "zoom" versus full maximization, can be configured in some environments like macOS.[66] Theming at the operating system level governs the title bar's appearance, including its height, which typically ranges from 20 to 32 pixels depending on the platform and scaling settings, and font styles that align with system-wide typography for consistency.[65] For instance, Windows Vista introduced the Aero theme in 2007, applying translucent glass-like effects and rounded aesthetics to title bars, which influenced subsequent OS designs by emphasizing visual depth and reduced opacity.[67] These elements are framed by the window's borders, ensuring the title bar integrates seamlessly with the overall window structure.[68]Icons and Status Indicators

In graphical user interfaces, the title bar icon serves as a small graphical representation of the application, typically sized at 16x16 pixels, positioned 16 pixels from the left border in left-to-right layouts or from the right in right-to-left layouts, and centered vertically within the 32-pixel-high title bar.[69] This icon, often an application logo or simplified favicon, primarily identifies the app to users and facilitates interactions such as task switching previews, where hovering over taskbar thumbnails displays the icon alongside the window preview, and context menus accessed via single-click or right-click on the icon itself.[69] Double-clicking the icon typically closes the window, providing a quick alternative to the standard close button.[69] Document status icons appear within the title bar to convey the current state of the file or content, such as an asterisk (*) appended directly next to the document title to indicate unsaved changes, alerting users to potential data loss if the window is closed without saving.[70] In applications like Microsoft Word, this indicator integrates seamlessly with the title text, updating dynamically as edits occur and disappearing upon successful save, ensuring users maintain awareness of the document's modification status without disrupting workflow.[70] For read-only files, the title bar may display textual indicators like "[Read-Only]" adjacent to the title, signaling restricted editing permissions due to file properties or security settings.[71] System tray icons, located in the notification area of the taskbar, represent minimized windows or background applications, allowing persistent access without occupying screen space.[72] These icons, often 16x16 or 32x32 pixels for high-DPI compatibility, are added via system APIs like Shell_NotifyIcon and include tooltips that display on hover, providing concise status information or quick-launch options for the associated window.[72] Left-clicking typically restores or interacts with the minimized application, while right-clicking opens a context menu for additional controls, enhancing usability in multitasking environments across operating systems like Windows.[72] The evolution of icons in windowing systems began with monochrome bitmaps in early GUIs, such as the black-and-white icons in the ICO format introduced in Windows 1.0 in 1985, which used simple 1-bit depth for basic representation on limited hardware.[73] By the 1990s, icons transitioned to color palettes with 16 or 256 colors in formats supporting multiple resolutions, as seen in Windows 95, to accommodate richer visual feedback.[73] In the post-2010s era, modern interfaces shifted to scalable vector graphics (SVG) for high-resolution displays, enabling crisp rendering at any size without pixelation, as implemented in systems like Windows 11's Fluent Design icons and Apple's SF Symbols library.[74] This vector-based approach prioritizes scalability and adaptability, supporting diverse screen densities while maintaining design consistency across devices.[74]Window Management

Floating Windows

Floating windows, also referred to as stacking windows, represent the traditional paradigm in window management where users manually control the position, size, layering, and overlap of individual windows on the display. This approach allows for arbitrary arrangement, enabling windows to partially or fully obscure one another based on user preference, in contrast to automated layouts that prevent overlaps. The model supports dynamic resizing and repositioning through direct manipulation, such as dragging or keyboard shortcuts, fostering a desktop metaphor akin to physical papers on a surface.[75] One key advantage of floating windows lies in their flexibility for handling complex multitasking workflows, where users can spatially organize applications to suit specific tasks, such as positioning a reference document beside an editor. This arrangement leverages human spatial memory, aiding quick retrieval and navigation by associating content with its on-screen location, as demonstrated in studies of overlapping interfaces that highlight improved task switching efficiency. For instance, users often drag windows side-by-side to monitor multiple streams of information simultaneously, enhancing productivity in non-linear work patterns.[75] Implementations of floating windows are prevalent in major desktop environments, including Microsoft Windows, which uses overlapped window styles for user-controlled positioning and z-order stacking; Apple macOS, with its Aqua interface supporting manual window arrangement; and KDE Plasma, where the KWin compositor exclusively handles floating windows by default. In extensible systems like the i3 tiling window manager, floating mode can be enabled via commands such asfloating enable, allowing selective override of automated tiling for specific windows. This paradigm has dominated since its introduction in the Xerox Alto system in 1973, influencing subsequent graphical interfaces.[39][76][77][78]

Despite these benefits, floating windows suffer from drawbacks related to screen real estate inefficiency, as overlaps can lead to visual clutter and obscured content, complicating visibility and requiring frequent window management actions. Tiling window managers address this by enforcing non-overlapping layouts as an alternative.[75]

Tiling Windows

Tiling window managers automate the arrangement of windows into non-overlapping regions on the screen, maximizing available space without manual dragging or resizing. Unlike floating windows, which permit user-driven overlaps and free positioning, tiling systems enforce algorithmic layouts to eliminate wasted space and promote efficient multitasking. These managers typically divide the screen dynamically into areas such as a primary "master" region for the focused window and a "stack" for secondary ones, or use binary tree structures where each split creates hierarchical containers for windows.[79][80][81] Resizing and layout adjustments are primarily handled through keyboard shortcuts, allowing users to split regions horizontally or vertically on the fly, often with configurable ratios for balanced proportions.[77][82] Popular implementations include xmonad, a Haskell-based tiling manager first released in April 2007, which supports extensible layouts like tabbed or mirrored arrangements and uses "manage hooks" to assign windows to specific workspaces based on rules such as class or title.[83][84] i3, released in 2009 and written in C, employs a tree-based container model for flexible tiling, stacking, or tabbing, with configuration rules that automatically direct windows to workspaces or set initial sizes.[85][86] dwm, developed by the suckless project starting in 2006, offers dynamic switching between tiled (master-stack), monocle (full-screen), and floating modes, using tags as lightweight workspaces where windows can be assigned via keyboard commands or rules in the source code.[87] These systems provide benefits such as optimal screen utilization by filling the display without gaps or overlaps, reducing reliance on the mouse for navigation and thus speeding up workflows for keyboard-centric users like developers.[88][79] They are particularly suited to power users, with adaptations like golden ratio splits—where new windows occupy approximately 61.8% of the parent container for aesthetically pleasing proportions—enhancing readability in code editors or documents.[77] Studies evaluating tiling features in traditional desktops have shown improved task efficiency in multi-window scenarios by minimizing visual clutter and search time.[89] However, tiling managers can be less intuitive for users accustomed to graphical applications requiring precise mouse interactions, as automatic arrangements may disrupt expected window behaviors like dragging elements.[90] They often demand initial configuration for exceptions, such as allowing popups or dialogs to float freely rather than tile, to avoid usability issues with transient windows.[87] This setup overhead and lack of built-in visual polish make them more appealing to advanced users than casual ones.[91]Implementations in Operating Systems

In Microsoft Windows, window management emphasizes integration with the taskbar, which provides thumbnails of open windows for quick switching and grouping, enhancing multitasking efficiency. Snap Assist, introduced in 2015 with Windows 10, automates tiling by suggesting complementary windows when one is snapped to a screen edge or corner, supporting floating and tiled layouts across multiple monitors. Windows 11, released in 2021, enhanced these with Snap Layouts—hover-activated suggestions for multi-window arrangements—and Snap Groups, which save and restore window configurations together for persistent workflows. As of 2025, these features remain central, with Windows 11 version 25H2 focusing on performance optimizations rather than new management tools.[92][44][93] For modern applications, WinUI serves as a native framework that standardizes window rendering and behaviors, incorporating Fluent Design elements for consistent user experiences in desktop and UWP apps.[94] Apple's macOS handles windows through the Dock, where minimized windows can be configured to stack into application icons or a dedicated section, facilitating easy restoration and organization. Mission Control, debuted in 2011 with OS X Lion, offers an overview of all open windows, full-screen apps, and spaces, allowing users to swipe or gesture to navigate and rearrange them dynamically. Recent versions have introduced Stage Manager (macOS Ventura 2022) for grouping related windows into stages visible alongside the focused app, and improved native window tiling with menu bar options and keyboard shortcuts (macOS Sonoma 2023 and Sequoia 2024), enabling easy side-by-side and quarter-screen arrangements. The Aqua interface theme features a unified title bar that merges the toolbar with window controls, positioning close, minimize, and full-screen buttons (known as traffic lights) on the left for a seamless, native look.[95][96][97][98][99] Linux and Unix-like systems exhibit varied window implementations depending on the display server protocol. Under X11, the traditional protocol, compositing is typically handled by separate window managers, leading to potential latency in rendering overlays and effects. Wayland, first released in 2012, integrates compositing directly into the protocol's compositors, improving security and performance by eliminating client-side rendering vulnerabilities inherent in X11. By 2025, Wayland has achieved widespread adoption as the default in major distributions including Fedora (since 2022), Ubuntu (24.04 LTS), and Debian, powering environments like GNOME and KDE. In the GNOME desktop environment, dynamic workspaces automatically adjust in number based on active windows, supporting fluid transitions between tasks without fixed limits.[100] KDE Plasma, conversely, employs configurable virtual desktops that users can name and assign windows to, with tools for per-desktop wallpapers and activities to segregate workflows.[101][33][102][103] Cross-platform frameworks like Electron, first committed to GitHub in 2013, enable consistent window behaviors across operating systems by leveraging Chromium's rendering engine, as seen in applications such as Visual Studio Code where BrowserWindow APIs manage sizing, positioning, and events uniformly.[104] On mobile hybrids, Android supports freeform windows in developer mode, allowing resizable, floating app instances on larger screens since Android 7.0 (2016), with standard multi-window features like split-screen and pop-up views becoming prevalent in tablets and foldables since Android 10 (2019).[105]Advanced Features

Transparency and Visual Effects

Transparency in graphical user interfaces allows windows to appear semi-transparent, enabling visual layering and depth without obscuring underlying content. This effect is achieved through alpha blending, a technique that combines pixel colors based on an alpha channel value representing opacity. In Windows Vista, released in 2007, the Aero Glass interface introduced widespread use of alpha blending for semi-transparent windows, particularly in window frames, taskbars, and menus, creating a glassy aesthetic.[106] This transparency extends to practical applications like drop shadows, which provide visual separation between windows and the desktop, and overlays such as live thumbnails for task switching, enhancing usability while maintaining a cohesive look.[106] Hardware acceleration via the Desktop Window Manager (DWM) ensures these effects render efficiently on compatible graphics cards.[106] Animations add dynamism to window interactions, with smooth transitions for opening, closing, resizing, and minimizing improving perceived responsiveness. In macOS, Core Animation framework handles these effects, including scale and fade transitions for window appearance, leveraging GPU acceleration to offload rendering from the CPU for high frame rates.[107] Introduced prominently in Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard (2007) and refined in subsequent versions, this system uses dedicated graphics hardware to achieve fluid motion, such as windows gently scaling up or fading in during launch.[107] Post-2000s advancements in GPU technology have made such animations standard across operating systems, reducing latency and enabling complex effects without compromising performance.[107] Compositing window managers integrate transparency and animations into a unified rendering pipeline, often relying on 3D graphics APIs for advanced effects. Compiz, a compositing window manager for the X Window System released in 2006, popularized features like wobbly windows—where dragged windows deform elastically—and cube desktops, which rotate workspaces in a 3D cube formation.[108] These effects require OpenGL support for hardware-accelerated 3D rendering, with minimum requirements including a compatible graphics card capable of texture-from-pixmap extensions like GLX_EXT_texture_from_pixmap.[108] Compiz's design allows plugins to extend core compositing, blending alpha transparency with geometric transformations for immersive desktop environments.[108] Recent trends in window visual effects emphasize integration with display technologies like variable refresh rate (VRR), which dynamically adjusts monitor refresh rates to match content frame rates, reducing tearing and enhancing fluidity in animations. In Windows 11, VRR support—introduced in Windows 10 Anniversary Update (2016) and expanded through DirectX 11/12—enables smoother window transitions and effects on compatible displays by reducing tearing in flip-model swap chains.[109] Similarly, macOS on Apple Silicon and recent Intel models incorporates VRR via Adaptive Sync for external displays, optimizing animation pacing in full-screen or windowed modes to achieve tear-free visuals on high-refresh-rate panels up to 120 Hz or more. By 2025, this integration has become standard in high-end operating systems, supporting fluid effects on OLED and mini-LED displays while minimizing power consumption in low-frame scenarios.Multi-Monitor and Cross-Platform Support

Modern windowing systems increasingly support multi-monitor configurations to enhance productivity by allowing users to extend their desktop across multiple displays. In such setups, windows can span across screens when displays are configured in extended mode, enabling seamless dragging of application windows from one monitor to another or resizing them to cover parts of multiple screens. For instance, Microsoft Windows 10, released in 2015, introduced enhancements like independent taskbars on each monitor and improved window snapping across displays, facilitating better organization of virtual desktops that span all connected screens while allowing per-monitor content management.[110] A key challenge in multi-monitor environments is handling DPI scaling mismatches, where monitors have different resolutions or pixel densities, leading to blurry or inconsistently sized UI elements when windows move between screens. Operating systems address this through per-monitor DPI awareness; Windows 10 and later versions support application-level DPI scaling, where apps can detect and adapt to the DPI of the monitor on which they are displayed, reducing visual artifacts. Similarly, macOS uses Retina scaling with automatic adjustments, though mismatches may require manual configuration, while Linux distributions with Wayland compositors offer fractional scaling per output to mitigate issues.[111] Cross-platform development poses additional challenges for consistent window behavior across operating systems, necessitating abstractions to unify window creation and management. The Qt framework, initiated in 1991, provides a cross-platform API for creating and managing windows on Windows, macOS, Linux, and embedded systems, abstracting native windowing APIs like Win32, Cocoa, and X11 to ensure uniform rendering and event handling. Likewise, Flutter, Google's UI toolkit, enables desktop window support across platforms from a single codebase, leveraging native controls for window lifecycle and integration while addressing platform-specific behaviors such as resizing and focus. Issues like gesture support in hybrid environments—such as touch vs. mouse inputs—remain problematic, as varying system-level gesture recognizers can lead to inconsistent interactions, requiring developers to implement custom mappings for multi-touch events.[112][113] The convergence of mobile and desktop paradigms has introduced windowed applications on tablets, bridging touch-based and traditional window management. Apple's iPadOS 16, released in 2022, introduced Stage Manager, which allows resizable, overlapping windows for up to four apps on-screen, with support for external displays to extend the workspace, mimicking desktop multitasking on iPad Pro models. Remote desktop protocols further enable windowed access to distant machines; Microsoft's Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) streams full desktop sessions as windows on local clients, supporting multi-monitor passthrough, while VNC protocols like TightVNC provide cross-platform remote control of windows over networks.[114][115][116] Standards like ICC profiles ensure color consistency across multi-monitor setups by defining device-specific color characteristics for accurate rendering. These profiles, managed by the International Color Consortium, allow operating systems to apply color transformations per monitor, preventing discrepancies when windows span displays with varying gamut or calibration. In the 2020s, window management has evolved for foldable devices, where screens unfold to create larger virtual displays; Samsung's Galaxy Z Fold series, for example, supports multi-active windows that adapt dynamically to folded or unfolded states, allowing apps to span hinges seamlessly. Microsoft provides emulation tools for developers to test foldable layouts, ensuring window continuity across form factors.[117][118][119][120]Accessibility and Usability Enhancements

Accessibility features in graphical user interfaces (GUIs) for windows prioritize inclusivity by addressing visual, auditory, and motor impairments. High-contrast modes, such as those available in Windows, adjust color schemes to enhance visibility for users with low vision, ensuring text and UI elements meet minimum contrast ratios like 4.5:1 for normal text.[121][122] Screen reader integration, exemplified by JAWS from Freedom Scientific, announces window focus changes and content updates to assist blind users, reading titles, status, and structural elements aloud.[123] Resizable text within windows allows scaling up to 200% without horizontal scrolling or loss of functionality, aligning with WCAG 2.1 guidelines to support users with visual impairments.[124] Usability enhancements extend these principles through intuitive controls that reduce physical and cognitive load. Keyboard navigation, including Windows' Win+Arrow key combinations for snapping windows to screen edges, enables efficient resizing and positioning without a mouse, benefiting users with motor disabilities.[44] Focus indicators, such as prominent outlines or color shifts around active elements, provide clear visual cues for low-vision users navigating via keyboard, requiring at least a 3:1 contrast ratio against surrounding areas per WCAG standards.[125] Auto-hide decorations, like the taskbar in Windows, maximize screen real estate by concealing non-essential UI elements until needed, improving workflow efficiency. Modern developments incorporate advanced technologies for broader accessibility. Voice control in macOS, introduced in Catalina and refined through Sonoma (2023), allows users to manipulate windows via spoken commands like "click window" or "scroll up," supporting those with severe motor limitations.[126] Features like Stage Manager, introduced in macOS Ventura (2022), group related windows into stages for easier organization, aiding multitasking for users with cognitive or attention-related needs.[127] In web-based windows, ARIA roles such as "window," "dialog," and "alertdialog" define semantic structures for assistive technologies, ensuring proper announcement of state changes like opening or focusing.[128] Usability studies evaluate these enhancements using metrics like time-to-task completion, where optimized window interactions improve efficiency in GUI evaluations.[129]References

- https://wiki.gentoo.org/wiki/Bspwm