Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Inkstone

View on Wikipedia| Inkstone | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 硯臺 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 砚台 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 墨硯 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 墨砚 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | nghiên | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 硯 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 벼루 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 硯 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | すずり | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Katakana | スズリ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

An inkstone is a stone mortar for the grinding and containment of ink.[1] In addition to stone, inkstones are also manufactured from clay, bronze, iron, and porcelain. The device evolved from a rubbing tool used for rubbing dyes dating around 6,000 to 7,000 years ago.[2] It is part of traditional Chinese stationery.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The inkstone is Chinese in origin and is used in calligraphy and painting. Extant inkstones date from early antiquity in China.

The device evolved from a rubbing tool used for rubbing dyes dating around 6,000 to 7,000 years ago.[2] The earliest excavated inkstone is dated from the 3rd century BC, and was discovered in a tomb located in modern Yunmeng, Hubei. Usage of the inkstone was popularized during the Han dynasty.[3]

Tang, Song, and Yuan dynasties

[edit]

Stimulated by the social economy and culture, the demand for inkstones increased during the Tang dynasty (618–905) and reached its height in the Song dynasty (960–1279). Song dynasty inkstones can be of great size and often display a delicacy of carving. Song dynasty inkstones can also exhibit a roughness in their finishing. Dragon designs of the period often reveal an almost humorous rendition; the dragons often seem to smile. From the subsequent Yuan dynasty, in contrast, dragons display a ferocious appearance.

Qing dynasty

[edit]The transition to civil rule under Kangxi Emperor in 1681 saw an increase in imperial inkstone production. Inkstones were often given as gifts, likely in part to help connect existing Chinese literati culture to the new Manchu imperial culture.[4][5]

The Qianlong Emperor had his own imperial collection of inkstones catalogued into a twenty-four chapter compendium entitled Xiqing yanpu (Hsi-ch'ing yen-p'u). Many of these inkstones are housed in the National Palace Museum collection in Taipei.

Qing dynasty emperors often had their inkstones made of Songhua stones, but this choice was not popular outside of the imperial workshop. Inkstone design outside the palace developed largely in parallel with imperial inkstone design, although they occasionally intersected.[4][5] Gu Erniang was the most famous inkstone-maker among Chinese scholars in the early Qing dynasty. Records indicate her inkstones were elegant and relatively simple, as was the preferred style at the time. However, by the late Qing dynasty, the inkstone market had turned to favoring highly intricate and novel designs.[6][7]

Material and construction

[edit]Inkstones can be made from a variety of materials, such as ceramics, lacquered wood, glass, or old bricks. However, they are typically made from stones harvested specifically for inkstone-making.[6] Different stones yield different quality ink; as such, the material of an inkstone is critical to its functionality. Inkstones made from the stones of specific quarries, and from specific caves within those quarries, are highly sought out by collectors.[4][8]

Quality of inkstones

[edit]Two types of rock are mainly used to make inkstones:[1]

- underwater eruptive rocks, such as the famous Chinese duānxī stone (端溪), in Japanese tankei 端渓;

- sedimentary rocks such as shexian stone, in Japanese kyūjū 歙州.

The ink stone consists of a flat part called the “hill” (qiū [丘] or gāng [冈]; oka [丘] or [岡] in Japanese), and a hollow part “the sea”, hǎi, 海 (umi in Japanese) intended to collect the ink created.

An ink stone is most appreciated for the grain, texture or even sound it produces when the Ink stick is rubbed against it in a circular motion:

If you strike the stone hanging on a hook, with a sharp blow with your finger, it should make a beautiful clear sound.” And also: “A good stone is distinguished first and foremost by the fineness and regularity of its grain. It has a softness and mellowness that you feel when you caress it with the palm of your hand. It has a satin sheen. Thanks to these qualities, it picks up the ink as the stick passes over it, accelerating the grinding process and producing fine, dense ink. An infinitesimal part of its grain is also said to pass into the ink, giving it a superior patina. On a stone that is too hard, the stick is not grasped but pushed away, it slips; the grinding is done irregularly and the ink is less beautiful...

— J.-F. Billeter[9]

The best stones have always come from Chinese quarries on the south bank of the Xijiang in Guangdong. But quarrying these stones was dangerous and strenuous, as they were usually found in caves particularly hard hit by violent floods. Even today, many mines are still in operation, and the oldest stones over a hundred years old, also known as guyàn / ko-ken (古硯), are much more sought-after than the newer ones known as xinyàn / shin-ken (新硯). Some regions of Japan also produce good quality stones.[1]

A beginner can use very simple stones, which can later be upgraded to higher-quality ink stones as they progress.

Four Famous Inkstones

[edit]Four kinds of Chinese inkstones are especially noted in inkstone art history and are popularly known as the "Four Famous Inkstones".

- Duan inkstones (simplified Chinese: 端砚; traditional Chinese: 端硯; pinyin: Duānyàn) are produced in Zhaoqing, Guangdong Province, and got its name from Duan Prefecture that governed the city during the Tang dynasty.[10] Duan stone is a volcanic tuff, commonly of a purple to a purple-red color. There are various distinctive markings, due to various rock materials imbedded in the stone, that create unique designs and stone eyes (inclusions) which were traditionally valued in China.[10] A green variety of the stone was mined in the Song dynasty. Duan inkstones are carefully categorized by the mines (k'eng) from which the raw stone was excavated. Particular mines were open only for discrete periods in history. For example, the Mazukeng mine was originally opened in the Qianlong reign (1736–1795), although reopened in modern times.

- She inkstones (simplified Chinese: 歙砚; traditional Chinese: 歙硯; pinyin: Shèyàn) come from She County (Anhui Province) and Wuyuan County (Jiangxi Province). Both counties were under jurisdiction of the ancient She Prefecture of Huizhou during the Tang dynasty when the She inkstone was first made. This stone is a variety of slate and like Duan stone is categorized by the various mines from which the stone was obtained historically. It has a black color and also displays a variety of gold-like markings.[11] She inkstones were first used during the Tang dynasty.[11]

- Tao(he) inkstones (simplified Chinese: 洮(河)砚; traditional Chinese: 洮(河)硯; pinyin: Táo(hé)yàn) are made from the stones found at the bottom of the Tao River in Gansu Province.[4] These inkstones were first used during the Song dynasty and became rapidly desired.[12] It bears distinct markings such as bands of ripples with varying shades.[12] The stone is crystalline and looks like jade. These stones have become increasingly rare and are difficult to find. It can easily be confused with a green Duan stone, but can be distinguished by its crystalline nature.

- Chengni inkstones (simplified Chinese: 澄泥砚; traditional Chinese: 澄泥硯; pinyin: Chéngníyàn) are ceramic-manufactured inkstones. This process began in the Tang dynasty and is said to have originated in Luoyang, Henan.

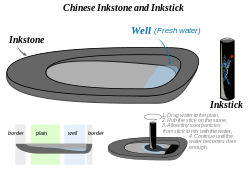

Usage

[edit]Traditional Chinese ink is solidified into inksticks. Usually, some water is applied onto the inkstone (by means of a dropper to control the amount of water) before the bottom end of the inkstick is placed on the grinding surface and then gradually ground to produce the ink.[13]

More water is gradually added during the grinding process to increase the amount of ink produced, the excess flowing down into the reservoir of the inkstone where it will not evaporate as quickly as on the flat grinding surface, until enough ink has been produced for the purpose in question.[13]

The Chinese grind their ink in a circular motion with the end flat on the surface whilst the Japanese push one edge of the end of the inkstick back and forth.

Water can be stored in a water-holding cavity on the inkstone itself, as was the case for many Song dynasty (960–1279) inkstones. The water-holding cavity or water reservoir in time became an ink reservoir on later inkstones. Water was usually kept in a ceramic container and sprinkled on the inkstone. The inkstone, together with the ink brush, inkstick and Xuan paper, are the four writing implements traditionally known as the Four Treasures of the Study.[14]

Gallery

[edit]-

She inkstone from the Song dynasty, China (Nantoyōsō Collection, Japan)

-

Taohe inkstone from the Song dynasty, China, with Ming dynasty inscription (Nantoyōsō Collection, Japan)

-

Inkstone with jar pattern, c. 1800–1894, from the Oxford College Archives of Emory University

-

Earthenware inkstone and cover in the shape of a turtle, ca. 6th–7th century, from the Metropolitan Museum

-

Yao Naiming inkstone

-

Inkstone of Jin dynasty

-

A lotus leaf–shaped Duan inkstone

-

Inkstone in Anyang Museum

-

Tức Mặc Hầu, a inkstone owned by emperor Tự Đức.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Durix, Claude (2000-01-01). Ecrire l'éternité (in French). Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 2-251-49013-2.

- ^ a b Tingyou Chen (3 March 2011). Chinese Calligraphy. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-18645-2.

- ^ China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 AD. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2004. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-58839-126-1.

- ^ a b c d "Gansu Tao Inkstone". chinaculture.org. Ministry of Culture, P.R.China. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ a b Ko, Dorothy (2017). The social life of inkstones : artisans and scholars in early Qing China. Seattle. pp. 62–65. ISBN 978-0-295-99919-7. OCLC 1298399895.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Ko, Dorothy (2017). The social life of inkstones : artisans and scholars in early Qing China. Seattle. pp. 20–22. ISBN 978-0-295-99919-7. OCLC 1298399895.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ko, Dorothy (2017). The social life of inkstones : artisans and scholars in early Qing China. Seattle. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-295-99919-7. OCLC 1298399895.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ko, Dorothy (2017). The social life of inkstones : artisans and scholars in early Qing China. Seattle. pp. 88–99. ISBN 978-0-295-99919-7. OCLC 1298399895.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ J.-F. Billeter, in Claude Durix, Écrire l'éternité. L'art de la calligraphie chinoise et japonaise, see bibliography.

- ^ a b Zhang, Wei (2004). The four treasures: inside the scholar's studio. San Francisco: Long River Press. pp. 39–41. ISBN 1-59265-015-5.

- ^ a b Zhang, Wei (2004). The four treasures: inside the scholar's studio. San Francisco: Long River Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 1-59265-015-5.

- ^ a b Zhang, Wei (2004). The four treasures: inside the scholar's studio. San Francisco: Long River Press. pp. 49–52. ISBN 1-59265-015-5.

- ^ a b Mi Fu, Robert Hans Van Gulik. Mi Fu on Ink-stones (2018), 84 pages, ISBN 978-9745241558

- ^ Ko, Dorothy (2017). The social life of inkstones : artisans and scholars in early Qing China. Seattle. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-295-99919-7. OCLC 1298399895.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

References

[edit]- T.C.Lai, Treasures of a Chinese Studio, Hong Kong, 1976.

- Kitabatake Sōji and Kitabatake Gotei, Chūgoku kenzai shūsei (A Compendium on Chinese Inkstones), Tokyo, 1980.

- Kitabatake Sōji and Kitabatake Gotei, Suzuri-ishi gaku (An Inkstone Encyclopedia), Tokyo, 1977.

- Yin-ting hsi-ch'ing yen-p'u (An Imperial Catalogue of the Western Brightness Collection of Inkstones), 24 chapters, preface 1778.