Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

| Tao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 道 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | way | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | đạo | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 道 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 도 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 道 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 道 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| English name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| English | /daʊ/ DOW, /taʊ/ TOW | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Tao or Dao (Chinese: 道; pinyin: dào; Jyutping: dou6) is the source and fundamental principle of the universe,[1][2] primarily as conceived in East Asian philosophy and religions. The concept is represented by the Chinese character 道, which has meanings including 'way', 'path', 'road', and sometimes 'doctrine' or 'principle'.[3]

According to Tao Te Ching, Tao is self-existent, formless, eternal, omnipresent, and is the source of all existence. While all phenomena in the universe change continuously, Tao, as the source of all, remains motionless and changeless intrinsically :

There is something undifferentiated and yet complete.

Which existed before heaven and earth.

Soundless and formless.

It depends on nothing and does not change.

It operates everywhere and is free from danger.

It may be considered the Mother of the universe.

I do not know its name; I call it Tao.

Tao is also described as invisible, intangible, and beyond intellectual understanding, as it is written in Tao Te Ching :

We look at it, and we do not see it, and we name it 'the Equable.'

We listen to it, and we do not hear it, and we name it 'the Inaudible.'

We try to grasp it, and do not get hold of it, and we name it 'the Subtle.'

With these three qualities, it cannot be made the subject of description;

and hence we blend them together and obtain The One.

- ━━━ from Chapter 14 of Tao Teh Ching [7]

Other chapters of Tao Te Ching, as well as other Taoist scriptures such as Ultra Supreme Elder Lord's Ultra Plainness Scripture, and The Wonderful Scripture on the Constant Purity and Tranquility Spoken by the Ultra Supreme Elder Lord, etc., reiterate that Tao is formless, invisible, omnipresent, and is the source of all.[8][9][10][11]

Based on these descriptions, Tao is considered to be the Absolute Truth independent of any conditions, and the Ultimate Reality behind all phenomena. It is the underlying natural order of the universe whose ultimate essence is difficult to circumscribe because it is non-conceptual yet evident in one's being of aliveness.

Personification of Tao

[edit]In Tao Te Ching, Tao is often described as a feminine concept or figure. For example, in some chapters, Tao is described as the Mother of the universe who gives birth to all existence and sustains them[12][13], while in some other chapters, the practice of adhering to Tao is called "keeping to the Mother", "keeping to the Feminine" or "being fed by the Mother".[14][15][16][17][18][19]

Additionally, some ancient Chinese classics describe a supreme goddess considered an embodiment of Tao, known as Holy Mother the Original Lord (聖母元君), Ultimate One Original Lord (太一元君), Uncreated Original Empress (先天元后), Supreme Original Lord (無上元君), etc.[20][21][22] According to the ancient classics, She is the teacher of Yellow Emperor, Lao Tzu and Ninth Heaven Mysterious Goddess (九天玄女).[23][24][25]

According to Taoist Scriptures, Ultra Supreme Elder Lord (太上老君) is also an embodiment of Tao, and the historical Lao Tzu is considered an incarnation of him.[26][27][28]

Description and uses of the concept

[edit]The word "Tao" has a variety of meanings in both the ancient and modern Chinese language. Aside from its purely prosaic use meaning road, channel, path, principle, or similar,[29] the word has acquired a variety of differing and often confusing metaphorical, philosophical, and religious uses. In most belief systems, the word is used symbolically in its sense of "way" as the right or proper way of existence, or in the context of ongoing practices of attainment or of the full coming into being, or the state of enlightenment or spiritual perfection that is the outcome of such practices.[30]

Some scholars make sharp distinctions between the moral or ethical usage of the word "Tao" that is prominent in Confucianism and religious Taoism and the more metaphysical usage of the term used in philosophical Taoism and most forms of Mahayana Buddhism;[31] others maintain that these are not separate usages or meanings, seeing them as mutually inclusive and compatible approaches to defining the principle.[32]

Conventionally used to refer to something that cannot otherwise be discussed in words, the term was originally used as a form of praxis rather than theory. Early writings such as the Tao Te Ching and I Ching are careful to distinguish between conceptions of the Tao (sometimes referred to as "named Tao") and the Tao itself (the "unnamed Tao"), which cannot be expressed or understood in language.[note 1][note 2][33] Liu Da asserts that the Tao is properly understood as an experiential and evolving concept and that there are not only cultural and religious differences in the interpretation of the Tao but personal differences that reflect the character of individual practitioners.[34]

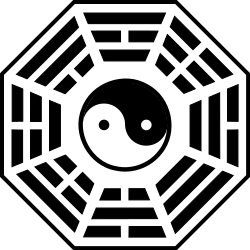

The Tao can be roughly thought of as the "flow of the universe", or as some essence or pattern behind the natural world that keeps the Universe balanced and ordered.[35] It is related to qi, the essential energy of action and existence. The Tao is a non-dualistic principle—it is the greater whole from which all the individual elements of the Universe derive. Catherine Keller considers it similar to the negative theology of Western scholars,[36] but the Tao is rarely an object of direct worship, being treated more like the Hindu concepts of karma, dharma, or Ṛta than as a divine object.[37] The Tao is more commonly expressed in the relationship between wu (void or emptiness, in the sense of wuji) and the natural, dynamic balance between opposites, leading to its central principle of wu wei (inaction or inexertion).

The Tao is usually described in terms of elements of nature, and in particular, as similar to water.[38][39] Like water it is undifferentiated, endlessly self-replenishing, soft and quiet but immensely powerful, and impassively generous.[note 3] The Song dynasty painter Chen Rong popularized the analogy with his painting Nine Dragons.[38]

Much of Taoist philosophy centers on the cyclical continuity of the natural world and its contrast to the linear, goal-oriented actions of human beings, as well as the perception that the Tao is "the source of all being, in which life and death are the same."[41]

In all its uses, the Tao is considered to have ineffable qualities that prevent it from being defined or expressed in words. It can, however, be known or experienced, and its principles (which can be discerned by observing nature) can be followed or practiced. Much of East Asian philosophical writing focuses on the value of adhering to the principles of the Tao and the various consequences of failing to do so.

The Tao was shared with Confucianism, Chan Buddhism and Zen, and more broadly throughout East Asian philosophy and religion in general. In Taoism, Chinese Buddhism, and Confucianism, the object of spiritual practice is to "become one with the Tao" (Tao Te Ching) or to harmonize one's will with nature to achieve 'effortless action'. This involves meditative and moral practices. Important in this respect is the Taoist concept of de ('virtue'). In Confucianism and religious forms of Taoism, these are often explicitly moral/ethical arguments about proper behavior, while Buddhism and more philosophical forms of Taoism usually refer to the natural and mercurial outcomes of action (comparable to karma). The Tao is intrinsically related to the concepts of yin and yang, where every action creates counter-actions as unavoidable movements within manifestations of the Tao, and proper practice variously involves accepting, conforming to, or working with these natural developments.

In Taoism and Confucianism, the Tao was sometimes traditionally seen as a "transcendent power that blesses" that can "express itself directly" through various ways, but most often shows itself through the speech, movement, or traditional ritual of a "prophet, priest, or king."[42] Tao can serve as a life energy instead of qi in some Taoist belief systems.[43]

De

[edit]De (德; 'power'', ''virtue'', ''integrity') is the term generally used to refer to proper adherence to the Tao. De is the active living or cultivation of the way.[44] Particular things (things with names) that manifest from the Tao have their own inner nature that they follow in accordance with the Tao, and the following of this inner nature is De. Wu wei, or 'naturalness', is contingent on understanding and conforming to this inner nature, which is interpreted variously from a personal, individual nature to a more generalized notion of human nature within the greater Universe.[45]

Historically, the concept of De differed significantly between Taoists and Confucianists. Confucianism was largely a moral system emphasizing the values of humaneness, righteousness, and filial duty, and so conceived De in terms of obedience to rigorously defined and codified social rules. Taoists took a broader, more naturalistic, more metaphysical view on the relationship between humankind and the Universe and considered social rules to be at best a derivative reflection of the natural and spontaneous interactions between people and at worst calcified structure that inhibited naturalness and created conflict. This led to some philosophical and political conflicts between Taoists and Confucians. Several sections of the works attributed to Zhuang Zhou are dedicated to critiques of the failures of Confucianism.

Interpretations

[edit]Taoism

[edit]The translator Arthur Waley observed that

[Tao] means a road, path, way; and hence, the way in which one does something; method, doctrine, principle. The Way of Heaven, for example, is ruthless; when autumn comes 'no leaf is spared because of its beauty, no flower because of its fragrance'. The Way of Man means, among other things, procreation; and eunuchs are said to be 'far from the Way of Man'. Chu Tao is 'the way to be a monarch', i.e. the art of ruling. Each school of philosophy has its tao, its doctrine of the way in which life should be ordered. Finally in a particular school of philosophy whose followers came to be called Taoists, tao meant 'the way the universe works'; and ultimately something very like God, in the more abstract and philosophical sense of that term.[46]

"Tao" gives Taoism its name in English, in both its philosophical and religious forms. The Tao is the fundamental and central concept of these schools of thought. Taoism perceives the Tao as a natural order underlying the substance and activity of the Universe. Language and the "naming" of the Tao is regarded negatively in Taoism; the Tao fundamentally exists and operates outside the realm of differentiation and linguistic constraints.[47]

There is no single orthodox Taoist view of the Tao. All forms of Taoism center around Tao and De, but there is a broad variety of distinct interpretations among sects and even individuals in the same sect. Despite this diversity, there are some clear, common patterns and trends in Taoism and its branches.[48]

The diversity of Taoist interpretations of the Tao can be seen across four texts representative of major streams of thought in Taoism. All four texts are used in modern Taoism with varying acceptance and emphasis among sects. The Tao Te Ching is the oldest text and representative of a speculative and philosophical approach to the Tao. The Daotilun is an eighth century exegesis of the Tao Te Ching, written from a well-educated and religious viewpoint that represents the traditional, scholarly perspective. The devotional perspective of the Tao is expressed in the Qingjing Jing, a liturgical text that was originally composed during the Han dynasty and is used as a hymnal in religious Taoism, especially among eremites. The Zhuangzi uses literary devices such as tales, allegories, and narratives to relate the Tao to the reader, illustrating a metaphorical method of viewing and expressing the Tao.[49]

The forms and variations of religious Taoism are incredibly diverse. They integrate a broad spectrum of academic, ritualistic, supernatural, devotional, literary, and folk practices with a multitude of results. Buddhism and Confucianism particularly affected the way many sects of Taoism framed, approached, and perceived the Tao. The multitudinous branches of religious Taoism accordingly regard the Tao, and interpret writings about it, in innumerable ways. Thus, outside of a few broad similarities, it is difficult to provide an accurate yet clear summary of their interpretation of the Tao.[50]

A central tenet in most varieties of religious Taoism is that the Tao is ever-present, but must be manifested, cultivated, and/or perfected to be realized. It is the source of the Universe, and the seed of its primordial purity resides in all things. Breathing exercises, according to some Taoists, allowed one to absorb "parts of the universe."[51] Incense and certain minerals were seen as representing the greater universe as well, and breathing them in could create similar effects.[citation needed] The manifestation of the Tao is de, which rectifies and invigorates the world with the Tao's radiance.[48]

Alternatively, philosophical Taoism regards the Tao as a non-religious concept; it is not a deity to be worshiped, nor is it a mystical Absolute in the religious sense of the Hindu brahman. Joseph Wu remarked of this conception of the Tao, "Dao is not religiously available; nor is it even religiously relevant." The writings of Laozi and Zhuangzi are tinged with esoteric tones and approach humanism and naturalism as paradoxes.[52] In contrast to the esotericism typically found in religious systems, the Tao is not transcendent to the self, nor is mystical attainment an escape from the world in philosophical Taoism. The self steeped in the Tao is the self grounded in its place within the natural Universe. A person dwelling within the Tao excels in themselves and their activities.[53]

However, this distinction is complicated by hermeneutic difficulties in the categorization of Taoist schools, sects, and movements.[54]

Some Taoists believe the Tao is an entity that can "take on human form" to perform its goals.[55]

The Tao represents human harmony with the universe and even more phenomena in the world and nature.

Confucianism

[edit]The Tao of Confucius can be translated as 'truth'. Confucianism regards the Way, or Truth, as concordant with a particular approach to life, politics, and tradition. It is held as equally necessary and well regarded as de and ren ('compassion', 'humanity'). Confucius presents a humanistic Tao. He only rarely speaks of the 'Way of Heaven'. The early Confucian philosopher Xunzi explicitly noted this contrast. Though he acknowledged the existence and celestial importance of the Way of Heaven, he insisted that the Tao principally concerns human affairs.[56]

As a formal religious concept in Confucianism, Tao is the Absolute toward which the faithful move. In Zhongyong (The Doctrine of the Mean), harmony with the Absolute is the equivalent to integrity and sincerity. The Great Learning expands on this concept explaining that the Way illuminates virtue, improves the people, and resides within the purest morality. During the Tang dynasty, Han Yu further formalized and defined Confucian beliefs as an apologetic response to Buddhism. He emphasized the ethics of the Way. He explicitly paired "Tao" and "De", focusing on humane nature and righteousness. He also framed and elaborated on a "tradition of the Tao" in order to reject the traditions of Buddhism.[56]

Ancestors and the Mandate of Heaven were thought to emanate from the Tao, especially during the Song dynasty.[57]

Buddhism

[edit]Buddhism first started to spread in China during the first century AD and was experiencing a golden age of growth and maturation by the fourth century AD. Hundreds of collections of Pali and Sanskrit texts were translated into Chinese by Buddhist monks within a short period of time. Dhyana was translated as 禅; chán, and later as "zen", giving Zen Buddhism its name. The use of Chinese concepts, such as the Tao, that were close to Buddhist ideas and terms helped spread the religion and make it more amenable to the Chinese people. However, the differences between the Sanskrit and Chinese terminology led to some initial misunderstandings and the eventual development of Buddhism in East Asia as a distinct entity. As part of this process, many Chinese words introduced their rich semantic and philosophical associations into Buddhism, including the use of "Tao" for central concepts and tenets of Buddhism.[58]

Pai-chang Huai-hai told a student who was grappling with difficult portions of suttas, "Take up words in order to manifest meaning and you'll obtain 'meaning'. Cut off words and meaning is emptiness. Emptiness is the Tao. The Tao is cutting off words and speech." Zen Buddhists regard the Tao as synonymous with both the Buddhist Path and the results of it, the Noble Eightfold Path and Buddhist enlightenment. Pai-chang's statement plays upon this usage in the context of the fluid and varied Chinese usage of "Tao". Words and meanings are used to refer to rituals and practices. The "emptiness" refers to the Buddhist concept of sunyata. Finding the Tao and Buddha-nature is not simply a matter of formulations, but an active response to the Four Noble Truths that cannot be fully expressed or conveyed in words and concrete associations. The use of "Tao" in this context refers to the literal "way" of Buddhism, the return to the universal source, dharma, proper meditation, and nirvana, among other associations. "Tao" is commonly used in this fashion by Chinese Buddhists, heavy with associations and nuanced meanings.[59]

Neo-Confucianism

[edit]During the Song dynasty, neo-Confucians regarded the Tao as the purest thing-in-itself. Shao Yong regarded the Tao as the origin of heaven, earth, and everything within them. In contrast, Zhang Zai presented a vitalistic Tao that was the fundamental component or effect of qi, the motive energy behind life and the world. A number of later scholars adopted this interpretation, such as Tai Chen during the Qing dynasty.[56]

Zhu Xi, Cheng Ho, and Cheng Yi perceived the Tao in the context of li ('principle') and t'ien li ('principle of Heaven'). Cheng Hao regarded the fundamental matter of li, and thus the Tao, to be humaneness. Developing compassion, altruism, and other humane virtues is following of the Way. Cheng Yi followed this interpretation, elaborating on this perspective of the Tao through teachings about interactions between yin and yang, the cultivation and preservation of life, and the axiom of a morally just universe.[56]

On the whole, the Tao is equated with totality. Wang Fuzhi expressed the Tao as the taiji, or 'great ultimate', as well as the road leading to it. Nothing exists apart from the Principle of Heaven in Neo-Confucianism. The Way is contained within all things. Thus, the religious life is not an elite or special journey for Neo-Confucians. The normal, mundane life is the path that leads to the Absolute, because the Absolute is contained within the mundane objects and events of daily life.[56]

Chinese folklore

[edit]Yayu, the son of Zhulong who was reincarnated on Earth as a violent hybrid between a bull, a tiger, and a dragon, was allowed to go to an afterlife that was known as "the place beyond the Tao".[60] This shows that some Chinese folk storytelling and mythological traditions had very differing interpretations of the Tao between each other and orthodox religious practices.

Christianity

[edit]Noted Christian author C.S. Lewis used the word Tao to describe "the doctrine of objective value, the belief that certain attitudes are really true, and others really false, the kind of thing the Universe is and the kind of things we are."[61] He asserted that every religion and philosophy contains foundations of universal ethics as an attempt to line up with the Tao—the way mankind was designed to be. In Lewis's thinking, God created the Tao and fully displayed it through the person of Jesus Christ.

Similarly, Eastern Orthodox hegumen Damascene (Christensen), a pupil of noted monastic and scholar of East Asian religions Seraphim Rose, identified logos with the Tao. Damascene published a full commented translation of the Tao Te Ching under the title Christ the Eternal Tao.[62]

In some Chinese translations of the New Testament, the word λόγος (logos) is translated as 道, in passages such as John 1:1, indicating that the translators considered the concept of Tao to be somewhat equivalent to the Hellenic concept of logos in Platonism and Christianity.[63]

Linguistic aspects

[edit]The Chinese character 道 is highly polysemous: its historical alternate pronunciation as dǎo possessed an additional connotation of 'guide'. The history of the character includes details of orthography and semantics, as well as a possible Proto-Indo-European etymology, in addition to more recent loaning into English and other world languages.

Orthography

[edit]"Tao" is written with the Chinese character 道 using both traditional and simplified characters. The traditional graphical interpretation of 道 dates back to the Shuowen Jiezi dictionary published in 121 CE, which describes it as a rare "compound ideogram" or "ideographic compound". According to the Shuowen Jiezi, 道 combines the 'go' radical 辶 (a variant of 辵) with 首; 'head'. This construction signified a "head going" or "leading the way".

"Tao" is graphically distinguished between its earliest nominal meaning of 'way', 'road', 'path', and the later verbal sense of 'say'. It should also be contrasted with 導; 'lead the way'', ''guide'', ''conduct'', ''direct'. The simplified character 导 for 導 has 巳; '6th of the 12 Earthly Branches' in place of 道.

The earliest written forms of "Tao" are bronzeware script and seal script characters from the Zhou dynasty (1045–256 BCE) bronzes and writings. These ancient forms more clearly depict the 首; 'head' element as hair above a face. Some variants interchange the 'go' radical 辵 with 行; 'go'', ''road', with the original bronze "crossroads" depiction written in the seal character with two 彳 and 亍; 'footprints'.

Bronze scripts for 道 occasionally include an element of 手; 'hand' or 寸; 'thumb'', ''hand', which occurs in 導; 'lead'. The linguist Peter A. Boodberg explained,

This "tao with the hand element" is usually identified with the modern character 導 tao < d'ôg, 'to lead,', 'guide', 'conduct', and considered to be a derivative or verbal cognate of the noun tao, "way," "path." The evidence just summarized would indicate rather that "tao with the hand" is but a variant of the basic tao and that the word itself combined both nominal and verbal aspects of the etymon. This is supported by textual examples of the use of the primary tao in the verbal sense "to lead" (e. g., Analects 1.5; 2.8) and seriously undermines the unspoken assumption implied in the common translation of Tao as "way" that the concept is essentially a nominal one. Tao would seem, then, to be etymologically a more dynamic concept than we have made it translation-wise. It would be more appropriately rendered by "lead way" and "lode" ("way," "course," "journey," "leading," "guidance"; cf. "lodestone" and "lodestar"), the somewhat obsolescent deverbal noun from "to lead."[64]

These Confucian Analects citations of dao verbally meaning 'to guide', 'to lead' are: "The Master said, 'In guiding a state of a thousand chariots, approach your duties with reverence and be trustworthy in what you say" and "The Master said, 'Guide them by edicts, keep them in line with punishments, and the common people will stay out of trouble but will have no sense of shame."[65]

Phonology

[edit]In modern Standard Chinese, 道's two primary pronunciations are tonally differentiated between falling tone dào; 'way', 'path' and dipping tone dǎo; 'guide', 'lead' (usually written as 導).

Besides the common specifications 道; dào; 'way' and 道; dǎo (with variant 導; 'guide'), 道 has a rare additional pronunciation with the level tone, dāo, seen in the regional chengyu 神神道道; shénshendāodāo; 'odd', 'bizarre', a reduplication of 道 and 神; shén; 'spirit', 'god' from northeast China.

In Middle Chinese (c. 6th–10th centuries CE) tone name categories, 道 and 導 were 去聲; qùshēng; 'departing tone' and 上聲; shǎngshēng; 'rising tone'. Historical linguists have reconstructed MC 道; 'way' and 導; 'guide' as d'âu- and d'âu (Bernhard Karlgren),[66] dau and dau[67] daw' and dawh,[68] dawX and daws (William H. Baxter),[69] and dâuB and dâuC.[70]

In Old Chinese (c. 7th–3rd centuries BCE) pronunciations, reconstructions for 道 and 導 are *d'ôg (Karlgren), *dəw (Zhou), *dəgwx and *dəgwh,[71] *luʔ,[69] and *lûʔ and *lûh.[70]

Semantics

[edit]The word 道 has many meanings. For example, the Hanyu Da Zidian dictionary defines 39 meanings for 道; dào and 6 for 道; dǎo.[72]

John DeFrancis's Chinese-English dictionary gives twelve meanings for 道; dào, three for 道; dǎo, and one for 道; dāo. Note that brackets clarify abbreviations and ellipsis marks omitted usage examples.

2dào 道 N. [noun] road; path ◆M. [nominal measure word] ① (for rivers/topics/etc.) ② (for a course (of food); a streak (of light); etc.) ◆V. [verb] ① say; speak; talk (introducing direct quote, novel style) ... ② think; suppose ◆B.F. [bound form, bound morpheme] ① channel ② way; reason; principle ③ doctrine ④ Daoism ⑤ line ⑥〈hist.〉 [history] ⑦ district; circuit canal; passage; tube ⑧ say (polite words) ... See also 4dǎo, 4dāo

4dǎo 导/道[導/- B.F. [bound form] ① guide; lead ... ② transmit; conduct ... ③ instruct; direct ...

4dāo 道 in shénshendāodāo ... 神神道道 R.F. [reduplicated form] 〈topo.〉[non-Mandarin form] odd; fantastic; bizarre[73]

Dao, starting from the Song dynasty, also referred to an ideal in Chinese landscape paintings that artists sought to live up to by portraying "nature scenes" that reflected "the harmony of man with his surroundings."[74]

Etymology

[edit]The etymological linguistic origins of dao "way; path" depend upon its Old Chinese pronunciation, which scholars have tentatively reconstructed as *d'ôg, *dəgwx, *dəw, *luʔ, and *lûʔ.

Boodberg noted that the shou 首 "head" phonetic in the dao 道 character was not merely phonetic but "etymonic", analogous with English to head meaning "to lead" and "to tend in a certain direction," "ahead," "headway".

Paronomastically, tao is equated with its homonym 蹈 tao < d'ôg, "to trample," "tread," and from that point of view it is nothing more than a "treadway," "headtread," or "foretread "; it is also occasionally associated with a near synonym (and possible cognate) 迪 ti < d'iôk, "follow a road," "go along," "lead," "direct"; "pursue the right path"; a term with definite ethical overtones and a graph with an exceedingly interesting phonetic, 由 yu < djôg," "to proceed from." The reappearance of C162 [辶] "walk" in ti with the support of C157 [⻊] "foot" in tao, "to trample," "tread," should perhaps serve us as a warning not to overemphasize the headworking functions implied in tao in preference to those of the lower extremities.[75]

Victor H. Mair proposes a connection with Proto-Indo-European drogh, supported by numerous cognates in Indo-European languages, as well as semantically similar Semitic Arabic and Hebrew words.

The archaic pronunciation of Tao sounded approximately like drog or dorg. This links it to the Proto-Indo-European root drogh (to run along) and Indo-European dhorg (way, movement). Related words in a few modern Indo-European languages are Russian doroga (way, road), Polish droga (way, road), Czech dráha (way, track), Serbo-Croatian draga (path through a valley), and Norwegian dialect drog (trail of animals; valley). .... The nearest Sanskrit (Old Indian) cognates to Tao (drog) are dhrajas (course, motion) and dhraj (course). The most closely related English words are "track" and "trek", while "trail" and "tract" are derived from other cognate Indo-European roots. Following the Way, then, is like going on a cosmic trek. Even more unexpected than the panoply of Indo-European cognates for Tao (drog) is the Hebrew root d-r-g for the same word and Arabic t-r-q, which yields words meaning "track, path, way, way of doing things" and is important in Islamic philosophical discourse.[76]

Axel Schuessler's etymological dictionary presents two possibilities for the tonal morphology of dào 道 "road; way; method" < Middle Chinese dâuB < Old Chinese *lûʔ and dào 道 or 導 "to go along; bring along; conduct; explain; talk about" < Middle dâuC < Old *lûh.[77] Either dào 道 "the thing which is doing the conducting" is a Tone B (shangsheng 上聲 "rising tone") "endoactive noun" derivation from dào 導 "conduct", or dào 導 is a Later Old Chinese (Warring States period) "general tone C" (qusheng 去聲 "departing tone") derivation from dào 道 "way".[78] For a possible etymological connection, Schuessler notes the ancient Fangyan dictionary defines yu < *lokh 裕 and lu < *lu 猷 as Eastern Qi State dialectal words meaning dào < *lûʔ 道 "road".

Other languages

[edit]Many languages have borrowed and adapted "Tao" as a loanword.

In Chinese, this character 道 is pronounced as Cantonese dou6 and Hokkian to7. In Sino-Xenic languages, 道 is pronounced as Japanese dō, tō, or michi; Korean do or to; and Vietnamese đạo.

Since 1982, when the International Organization for Standardization adopted Pinyin as the standard romanization of Chinese, many Western languages have changed from spelling this loanword tao in national systems (e.g., French EFEO Chinese transcription and English Wade–Giles) to dao in Pinyin.

The tao/dao "the way" English word of Chinese origin has three meanings, according to the Oxford English Dictionary.

1. a. In Taoism, an absolute entity which is the source of the universe; the way in which this absolute entity functions.

1. b. = Taoism, taoist

2. In Confucianism and in extended uses, the way to be followed, the right conduct; doctrine or method.

The earliest recorded usages were Tao (1736), Tau (1747), Taou (1831), and Dao (1971).

The term "Taoist priest" (道士; Dàoshì), was used already by the Jesuits Matteo Ricci and Nicolas Trigault in their De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas, rendered as Tausu in the original Latin edition (1615),[note 4] and Tausa in an early English translation published by Samuel Purchas (1625).[note 5]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Tao Te Ching, Chapter 1. "It is from the unnamed Tao

That Heaven and Earth sprang;

The named is but

The Mother of the ten thousand creatures." - ^ I Ching, Ta Chuan (Great Treatise). "The kind man discovers it and calls it kind;

the wise man discovers it and calls it wise;

the common people use it every day

and are not aware of it." - ^ Water is soft and flexible, yet possesses an immense power to overcome obstacles and alter landscapes, even carving canyons with its slow and steady persistence. It is viewed as a reflection of, or close in action to, the Tao. The Tao is often expressed as a sea or flood that cannot be dammed or denied. It flows around and over obstacles like water, setting an example for those who wish to live in accord with it.[40]

- ^ De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta ab Societate Jesu, Book One, Chapter 10, p. 125. Quote: "sectarii quidam Tausu vocant". Chinese gloss in Pasquale M. d' Elia, Matteo Ricci. Fonti ricciane: documenti originali concernenti Matteo Ricci e la storia delle prime relazioni tra l'Europa e la Cina (1579-1615), Libreria dello Stato, 1942; can be found by searching for "tausu". Louis J. Gallagher (China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matteo Ricci; 1953), apparently has a typo (Taufu instead of Tausu) in the text of his translation of this line (p. 102), and Tausi in the index (p. 615)

- ^ A discourse of the Kingdome of China, taken out of Ricius and Trigautius, containing the countrey, people, government, religion, rites, sects, characters, studies, arts, acts ; and a Map of China added, drawne out of one there made with Annotations for the understanding thereof (excerpts from De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas, in English translation) in Purchas his Pilgrimes, Volume XII, p. 461 (1625). Quote: "... Lauzu ... left no Bookes of his Opinion, nor seemes to have intended any new Sect, but certaine Sectaries, called Tausa, made him the head of their sect after his death..." Can be found in the full text of "Hakluytus posthumus" on archive.org.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Oxford Reference - Tao

- ^ Merriam-Webster Dictionary - Tao

- ^ Zai (2015), p. [page needed].

- ^ Tao Teh Ching Translations

- ^ Another translation of Chapter 25 of Tao Teh Ching : There is a thing that is perfect and complete in nature. It always exists, even before the creation of heaven and earth. Being quiescent and formless, it is self-existent and changeless. It circulates everywhere and never becomes exhausted. It is the Mother of heaven and earth. I do not know its name, but call it Tao.

- ^ Another translation of Chapter 25 of Tâo Teh King : There was something undefined and complete, coming into existence before Heaven and Earth. How still it was and formless, standing alone, and undergoing no change, reaching everywhere and in no danger (of being exhausted)! It may be regarded as the Mother of all things. I do not know its name, and I give it the designation of the Tao (the Way or Course).

- ^ The nature of Tao described in Chapter 14 of Tao Teh Ching

- ^ It is written in Ultra Supreme Elder Lord's Ultra Plainness Scripture :

The Way (Tao) is immense and formless, also hidden and nameless. Beyond Heaven and Earth, it is profound and unseen. Inside Heaven and Earth, it is ample and vigorous. The Way is everywhere between Heaven and Earth. - ^ It is written in The Wonderful Scripture on the Constant Purity and Tranquility, Spoken by the Ultra Supreme Elder Lord :

The Great Tao, being formless, creates heavens and earths;

The Great Tao, being emotionless, runs the sun and the moon;

The Great Tao, being nameless, eternally nurtures all beings.

I do not know its name, and artificially call it "Tao". - ^ Chapter 34 of Tao Teh Ching says :

The Way is broad, reaching to the left as well as right.

The myriad creatures depend on it for life yet it claims no authority.

It accomplishes its task yet lays claim to no merit.

It clothes and feeds the myriad creatures yet lays no claim to being their master. - ^ Another translation of Chapter 34 of Tâo Teh King :

All-pervading is the Great Tao! It may be found on the left hand and on the right. All things depend on it for their production, which it gives to them, not one refusing obedience to it. When its work is accomplished, it does not claim the name of having done it. It clothes all things as with a garment, and makes no assumption of being their lord. - ^ Tao Teh Ching Translations Chapter 25, 52, 51

- ^ A Comparison of the Femininity of Lady Wisdom of Proverbs in the Old Testament and Dao of Daodejing by Soon-Young Kim

- ^ Tao Teh Ching Translations Chapter 52, 28, 20

- ^ Chapter 52 of Tao Teh Ching :

There was a beginning of the universe

Which may be called the Mother of the Universe.

He who has found the mother (Tao)

And thereby understands her sons (things)

And having understood her sons,

Still keeps to its mother,

Will be free from danger throughout his lifetime. - ^ Another translation of Chapter 52 :

There was a beginning of the universe

Which may be regarded as the Mother of the Universe.

From the Mother, we may know her sons.

After knowing the sons, keep to the Mother.

Thus one's whole life may be preserved from harm. - ^ Chapter 28 of Tao Teh Ching :

Know the masculine.

Keep to the feminine.

And be the Brook of the World

To be the Brook of the World is

To move constantly in the path of Virtue

Without swerving from it

And to return again to infancy.

- ^ Another translation of Chapter 28 :

He who knows the male

and keeps to the female

Becomes the ravine of the world.

Being the ravine of the world.

He will never depart from eternal virtue.

But returns to the state of infancy. - ^ Chapter 20 of Tao Teh Ching :

I alone am different from others

And value being fed by the Mother. - ^ City Yung's Collective Record of Immortals (墉城集仙錄) : Holy Mother the Original Lord is an embodiment of the mysterious and harmonious energy of the Feminine Principle. She is the teacher of the Heavenly Emperor.

- ^ Master Loy's Spring and Autumn Annals (呂氏春秋.大樂) : Tao is the ultimate essence, which is formless and nameless. To name it artificially, it can be called Ultimate One. (道也者,至精也,不可為形,不可為名,強為之,謂之太一。)

- ^ The Ultimate One generates Water (太一生水) : Heaven and Earth are created by Ultimate One.

- ^ Heavenly Classic of the Seven Essences (雲笈七籤) : Ninth Heaven Mysterious Goddess is a disciple of Yellow Emperor's mentor known as Holy Mother the Original Lord.

- ^ Master who Embraces the Plainness (抱朴子) : Yellow Emperor and Lao Tzu received the essential teachings through learning from Ultimate One Original Lord.

- ^ Record of Immortals throughout the Ages (歷世真仙體道通鑑後集) : Lao Tzu traveled afar and arrived at Mountain Loe, where he met Ultimate One Original Lord. He learnt from her the secret teachings of Golden Elixir.

- ^ The Eighty-one Incarnations of the Elder Lord (老子八十一化) : The Elder Lord is the root of the Original Light, the true essence of creation. He is an embodiment of the Self-existent principle, which is Tao.

- ^ According to The Eighty-one Incarnations of the Elder Lord (老子八十一化), many important divine immortals in Taoist mythology are incarnations of the Elder Lord.

- ^ Heavenly Classic of the Seven Essences (雲笈七籤) : Lao Tzu is actually the Elder Lord, who is the embodiment of Tao, the source of the Original Energy, and the root of Heaven and Earth.

- ^ DeFrancis (1996), p. 113.

- ^ LaFargue (1992), pp. 245–247.

- ^ Chan (1963), p. 136.

- ^ Hansen (2000), p. 206.

- ^ Liu (1981), pp. 1–3.

- ^ Liu (1981), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Cane (2002), p. 13.

- ^ Keller (2003), p. 289.

- ^ LaFargue (1994), p. 283.

- ^ a b Carlson et al. (2010), p. 704.

- ^ Jian-guang (2019), pp. 754, 759.

- ^ Ch'eng & Cheng (1991), pp. 175–177.

- ^ Wright (2006), p. 365.

- ^ Carlson et al. (2010), p. 730.

- ^ "Taoism". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 2024-05-29.

- ^ Maspero (1981), p. 32.

- ^ Bodde & Fung (1997), pp. 99–101.

- ^ Waley (1958), p. [page needed].

- ^ Kohn (1993), p. 11.

- ^ a b Kohn (1993), pp. 11–12.

- ^ Kohn (1993), p. 12.

- ^ Fowler (2005), pp. 5–7.

- ^ "Daoism". Encarta. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28.

- ^ Moeller (2006), pp. 133–145.

- ^ Fowler (2005), pp. 5–6.

- ^ Mair (2001), p. 174.

- ^ Stark (2007), p. 259.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor & Choy (2005), p. 589.

- ^ Harl (2023), p. 272.

- ^ Dumoulin (2005), pp. 63–65.

- ^ Hershock (1996), pp. 67–70.

- ^ Ni (2023), p. 168.

- ^ Lewis, C.S. The Abolition of Man. p. 18.

- ^ Damascene (2012), p. [page needed].

- ^ Zheng (2017), p. 187.

- ^ Boodberg (1957), p. 599.

- ^ Lau (1979), p. 59, 1.5; p. 63, 2.8.

- ^ Karlgren (1957), p. [page needed].

- ^ Zhou (1972), p. [page needed].

- ^ Pulleyblank (1991), p. 248.

- ^ a b Baxter (1992), pp. 753.

- ^ a b Schuessler (2007), p. [page needed].

- ^ Li (1971), p. [page needed].

- ^ Hanyu Da Zidian (1989), pp. 3864–3866.

- ^ DeFrancis (2003), pp. 172, 829.

- ^ Meyer (1994), p. 96.

- ^ Boodberg (1957), p. 602.

- ^ Mair (1990), p. 132.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), p. 207.

- ^ Schuessler (2007), pp. 48–41.

Works cited

[edit]- Baxter, William H. (1992). A Handbook of Old Chinese Phonology. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-110-12324-1.

- Bodde, Derk; Fung, Yu-Lan (1997). A short history of Chinese philosophy. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-83634-3.

- Boodberg, Peter A. (1957). "Philological Notes on Chapter One of the Lao Tzu". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 20 (3/4): 598–618. doi:10.2307/2718364. JSTOR 2718364.

- Cane, Eulalio Paul (2002). Harmony: Radical Taoism Gently Applied. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 1-4122-4778-0.

- Carlson, Kathie; Flanagin, Michael N.; Martin, Kathleen; Martin, Mary E.; Mendelsohn, John; Rodgers, Priscilla Young; Ronnberg, Ami; Salman, Sherry; Wesley, Deborah A. (2010). Arm, Karen; Ueda, Kako; Thulin, Anne; Langerak, Allison; Kiley, Timothy Gus; Wolff, Mary (eds.). The Book of Symbols: Reflections on Archetypal Images. Köln: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-1448-4.

- Chang, Stephen T. (1985). The Great Tao. Tao Publishing, imprint of Tao Longevity. ISBN 0-942196-01-5.

- Ch'eng, Chung-Ying; Cheng, Zhongying (1991). New dimensions of Confucian and Neo-Confucian philosophy. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-0283-5.

- Chan, Wing-tsit (1963). A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton. ISBN 0-691-01964-9.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Damascene, Hieromonk (2012). Christ the Eternal Tao (6th ed.). Valaam Books.

- DeFrancis, John, ed. (1996). ABC Chinese-English Dictionary: Alphabetically Based Computerized (ABC Chinese Dictionary). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1744-3.

- DeFrancis, John, ed. (2003). ABC Chinese-English Comprehensive Dictionary. University of Hawaii Press.

- Dumoulin, Henrik (2005). Zen Buddhism: a History: India and China. Translated by Heisig, James; Knitter, Paul. World Wisdom. ISBN 0-941532-89-5.

- Fowler, Jeaneane (2005). An introduction to the philosophy and religion of Taoism: pathways to immortality. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 1-84519-085-8.

- Hansen, Chad D. (2000). A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought: A Philosophical Interpretation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513419-2.

- Hanyu Da Zidian (in Chinese). Vol. 6. Wuhan: Hubei Cishu Chubanshe. 1989. ISBN 978-7-5403-0022-7.

- Harl, Kenneth W. (2023). Empires of the Steppes: A History of the Nomadic Tribes Who Shaped Civilization. United States: Hanover Square Press. ISBN 978-1-335-42927-8.

- Hershock, Peter (1996). Liberating intimacy: enlightenment and social virtuosity in Ch'an Buddhism. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-2981-4.

- Jian-guang, Wang (December 2019). "Water Philosophy in Ancient Society of China: Connotation, Representation, and Influence" (PDF). Philosophy Study. 9 (12): 750–760.

- Karlgren, Bernhard (1957). Grammata Serica Recensa. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities.

- Keller, Catherine (2003). The Face of the Deep: A Theology of Becoming. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25648-8.

- Kirkland, Russell (2004). Taoism: The Enduring Tradition. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26321-4.

- Kohn, Livia (1993). The Taoist experience. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-1579-1.

- Komjathy, Louis (2008). Handbooks for Daoist Practice. Hong Kong: Yuen Yuen Institute.

- LaFargue, Michael (1994). Tao and Method: A Reasoned Approach to the Tao Te Ching. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-1601-1.

- LaFargue, Michael (1992). The tao of the Tao te ching: a translation and commentary. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-0986-4.

- Lau (1979). The Analects (Lun yu). Translated by Lau, D. C. Penguin.

- Li, Fanggui (1971). "Shanggu yin yanjiu" 上古音研究. Tsinghua Journal of Chinese Studies (in Chinese). 9: 1–61.

- Liu, Da (1981). The Tao and Chinese culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-7100-0841-4.

- Mair, Victor H. (1990). Tao Te Ching: The Classic Book of Integrity and the Way, by Lao Tzu; an entirely new translation based on the recently discovered Ma-wang-tui manuscripts. Bantam Books.

- Mair, Victor H. (2001). The Columbia History of Chinese Literature. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10984-9.

- Martinson, Paul Varo (1987). A theology of world religions: Interpreting God, self, and world in Semitic, Indian, and Chinese thought. Augsburg Publishing House. ISBN 0-8066-2253-9.

- Maspero, Henri (1981). Taoism and Chinese Religion. Translated by Kierman, Frank A. Jr. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-308-4.

- Meyer, Milton Walter (1994). China: A Concise History (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Littlefield Adams Quality Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-8476-7953-9.

- Moeller, Hans-Georg (2006). The Philosophy of the Daodejing. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13679-X.

- Ni, Xueting C. (2023). Chinese Myths: From Cosmology and Folklore to Gods and Immortals. London: Amber Books. ISBN 978-1-83886-263-3.

- Pulleyblank, E.G. (1991). Lexicon of Reconstructed Pronunciation in Early Middle Chinese, Late Middle Chinese, and Early Mandarin. UBC Press.

- Schuessler, Axel (2007). ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2975-9.

- Sharot, Stephen (2001). A Comparative Sociology of World Religions: virtuosos, priests, and popular religion. New York: NYU Press. ISBN 0-8147-9805-5.

- Stark, Rodney (2007). Discovering God: The Origins of the Great Religions and the Evolution of Belief (1st ed.). New York: HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-117389-9.

- Sterckx, Roel (2019). Chinese Thought. From Confucius to Cook Ding. London: Penguin.

- Taylor, Rodney Leon; Choy, Howard Yuen Fung (2005). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Confucianism, Volume 2: N-Z. Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8239-4081-0.

- Waley, Arthur (1958). The way and its power: a study of the Tao tê ching and its place in Chinese thought. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-5085-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Watts, Alan Wilson (1977). Tao: The Watercourse Way with Al Chung-liang Huang. Pantheon. ISBN 0-394-73311-8.

- Wright, Edmund, ed. (2006). The Desk Encyclopedia of World History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-7394-7809-7.

- Zai, J. (2015). Taoism and Science: Cosmology, Evolution, Morality, Health and more. Ultravisum. ISBN 978-0-9808425-5-5.

- Zheng, Yangwen, ed. (2017). Sinicizing Christianity. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-33038-2.

- Zhou Fagao (周法高) (1972). "Shanggu Hanyu he Han-Zangyu" 上古漢語和漢藏語. Journal of the Institute of Chinese Studies of the Chinese University of Hong Kong (in Chinese). 5: 159–244.

Further reading

[edit]- Translation of the Tao te Ching by Derek Lin

- Translation of the Dao de Jing by James Legge

- Legge translation of the Tao Teh King at Project Gutenberg

- Feng, Gia-Fu & Jane English (translators). 1972. Laozi/Dao De Jing. New York: Vintage Books.

- Komjathy, Louis. Handbooks for Daoist Practice. 10 vols. Hong Kong: Yuen Yuen Institute, 2008.

- Mitchell, Stephen (translator). 1988. Tao Te Ching: A New English Version. New York: Harper & Row.

- Robinet, Isabelle; Brooks, Phyllis; Robinet, Isabelle (1997). Taoism: growth of a religion. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2839-3.

- Sterckx, Roel. Chinese Thought. From Confucius to Cook Ding. London: Penguin, 2019.

- Dao entry from Center for Daoist Studies

- The Tao of Physics, Fritjof Capra, 1975

External links

[edit]Core Concept and Definition

Etymology and Terminology

The Chinese character 道 (dào) is composed of the radical 辶 (chuò), denoting movement or walking, combined with 首 (shǒu), meaning "head," yielding an etymological sense of "leading the way" or "path followed by the head."[7][8] Its core literal meanings encompass "road," "path," "method," and "principle," usages traceable to early classical Chinese literature predating philosophical systematization.[9][10] In Romanization systems, 道 is transcribed as "Tao" under Wade-Giles, a method developed in the 19th century by British sinologist Thomas Wade and refined by Herbert Giles, which approximates the sound but treats the unaspirated /d/ as aspirated /t/.[11] Hanyu Pinyin, standardized by the People's Republic of China in February 1958 and adopted internationally by ISO in 1982, renders it as "dào," more accurately reflecting the phonology of modern Standard Mandarin with its falling tone.[12][11] The shift from "Tao" to "Dao" in contemporary scholarship aligns with Pinyin's prevalence, though "Tao" persists in older English translations and popular contexts due to entrenched usage in works like James Legge's 1891 rendition of the Dao De Jing.[13] Terminologically, dào exhibits polysemy, extending beyond physical routes to doctrinal or moral "ways" in pre-Qin texts, such as Confucian emphases on ritual paths, before its metaphysical connotation as the ineffable cosmic principle in Daoist thought.[14] This evolution underscores its role as a foundational concept in Chinese philosophy, distinct from narrower senses like "to speak" or "to moralize."[15] In non-Mandarin Sinitic languages, cognates include Cantonese "dou6" and Japanese "michi" or "dō," adapting the term to local phonologies while retaining semantic cores of "way."[16]Primary Philosophical Meaning

In Daoist philosophy, Tao (道), romanized as Dao in modern pinyin, primarily signifies the foundational principle underlying the structure and processes of the universe, often rendered in English as "the Way." This concept denotes not merely a physical path but a metaphysical reality that encompasses the origin, pattern, and ongoing dynamism of all existence, functioning as an impersonal, self-sustaining order without anthropomorphic attributes.[1][4] The Tao Te Ching, attributed to Laozi around the 6th century BCE, posits the Dao as eternal and generative, from which the myriad things emerge through natural differentiation, yet it remains prior to and independent of named categories or human constructs.[17] Central to this meaning is the Dao's ineffability and transcendence of linguistic or conceptual grasp, as expressed in the text's first chapter: "The Dao that can be told is not the constant Dao; the name that can be named is not the constant name." It embodies a holistic unity beyond binaries like being and non-being, serving as both the undifferentiated source (wu, or non-being) and the manifest patterns (you, or being) observed in natural phenomena.[1][17] Empirical alignment with the Dao prioritizes observation of causal regularities in nature—such as cyclical processes in seasons, water's adaptive flow, or organic growth—over contrived interventions, fostering a realism grounded in what unfolds spontaneously rather than ideologically imposed ideals.[18][19] The philosophical imperative derived from the Dao emphasizes wu wei (non-coercive action), a mode of efficacy achieved by harmonizing with inherent tendencies rather than forcing outcomes, which yields resilience and adaptability as evidenced in natural systems like ecosystems or fluid dynamics. This contrasts with Confucian emphases on ritualized social order, viewing the Dao instead as a normative guide for human conduct through unadorned simplicity and detachment from ego-driven pursuits.[1][18] Scholarly interpretations, such as those in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, underscore the Dao as a "structure of natural possibility," where ethical and cosmological insights arise from first-hand engagement with unfolding realities rather than abstract theorizing.[1]Relation to De (Virtue)

In Daoist philosophy, de (德), often translated as "virtue" or "power," denotes the particular efficacy or potency that manifests when an entity aligns with the dao (道), the fundamental way or structure of natural possibilities.[1] This relation positions de not as an abstract moral quality in the Confucian sense of ritual propriety, but as the internal capacity enabling beings to navigate and realize the dao's dynamic paths through adaptive, effortless action (wu-wei).[4] For instance, the Dao De Jing describes the dao as producing all things, with de serving to rear, shape, and sustain them without coercion, as in Chapter 51: "Dao gives them life. De rears them. The material world gives them form. Circumstances give them substance." The Dao De Jing, traditionally attributed to Laozi and composed around the late Warring States period (circa 4th–3rd century BCE), structurally underscores this interdependence by dividing into a Dao jing (chapters 1–37) expounding the dao as the originating, ineffable source, and a De jing (chapters 38–81) detailing de as its concrete expression in sagely conduct.[4] Here, de emerges solely from the dao, fostering spontaneous harmony rather than deliberate ethics; Chapter 38 states that when de is lost, contrived virtues arise, inverting natural order. Sages embody de by mirroring the dao's fluidity, acting with "profound virtue" that benefits without possession or claim, as exemplified in Chapter 81: "The way of the sage is to act but not to possess, to achieve without taking credit."[20] Philosophically, de thus functions as the dao's localized realization, distributed across bodily and environmental know-how rather than centralized intellect, allowing entities like water to "excel in benefiting all things without striving" (Chapter 8).[1] This contrasts with imposed norms, emphasizing de's role in normative autonomy: beings with cultivated de select among the dao's permissible paths, promoting pluralism and adaptation over rigid hierarchies.[1] In the Zhuangzi, a complementary text, de appears as achieved through meditative unity with the dao, yielding transformative skill without egoistic attachment.[4] Overall, the dao-de nexus prioritizes causal alignment with natural processes, yielding efficacy as a byproduct of non-interference rather than intentional cultivation.[1]Linguistic Analysis

Orthography and Phonology

The Chinese character for Tao is 道, a phono-semantic compound (形聲字) formed by the semantic radical 辶 (chùò), indicating paths or movement, and the phonetic component 首 (shǒu), which provided the approximate pronunciation in ancient times. This structure reflects its core meaning related to "way" or "path," with 首 originally denoting "head" but serving primarily as a sound cue.[10] The character appears consistently in both traditional and simplified Chinese orthographies, with no variants in modern usage.[21] In standard Mandarin Chinese, 道 is pronounced dào in Hanyu Pinyin, with an unaspirated voiceless dental stop /t/, a diphthong /aʊ/, and a falling (fourth) tone [tɑʊ̯⁵¹].[22] Earlier Western romanizations, such as Wade-Giles (developed in the 19th century), render it as Tao⁴, reflecting a closer approximation to the perceived English-equivalent vowel but without distinguishing aspiration levels explicitly.[13] Hanyu Pinyin, officially adopted in mainland China in 1958, uses Dào to better indicate the unaspirated initial, distinguishing it from aspirated tāo (e.g., for 討).[23] Historically, the phonology evolved from Old Chinese *lˤuʔ (Baxter-Sagart reconstruction), featuring a lateral initial with retroflex articulation and a glottal stop coda, to Middle Chinese dɑuX (601 AD Qieyun system), with a dental initial, open diphthong, and rising tone (X category). This shift involved loss of the lateral and retroflex features, merger into dental stops, and tone development from final stops, as evidenced in rhyme dictionaries like the Qieyun. Modern Mandarin pronunciation derives from northern Late Middle Chinese varieties, with further diphthongization and tone simplification.[22]Semantics and Polysemy

The Chinese character 道 (dào) exhibits polysemy, encompassing literal, methodological, moral, and cosmological senses that evolved from its core denotation as a physical "path," "road," or "way." Etymologically, it combines the radical 辶 (chuò, indicating movement or walking) with 首 (shǒu, "head"), evoking the image of purposeful traversal or leading along a route, which integrates nominal and verbal functions such as "to guide" or "to proceed."[24][25] In pre-Qin texts like the Shījīng and Zhōuyì, dào primarily refers to concrete pathways, as in the phrase "履道坦坦" (lǚ dào tǎn tǎn), describing treading a level road, or watercourses symbolizing life's journey.[24] This literal sense extends semantically to abstract "methods," "skills," or "procedures" for action, including ethical or practical doctrines, as seen in early Zhou usages like "way of kings" in the Shàngshū, where it denotes normative paths for governance or conduct.[24][25] Classical Chinese lacks explicit singular-plural distinctions, enabling dào to flexibly denote singular cosmic principles or multiple contextual "ways" (e.g., réndào, "human way," for social practices), which schools like Confucianism and Legalism adapted for moral norms or strategic arts, such as in Sunzi's Art of War.[25] A further verbal sense, "to speak" or "discourse," arises from guiding via words, linking dào to teachings or sayings that articulate principles.[25] In philosophical contexts, particularly Daoism, dào abstracts to the ineffable cosmic process or generative force underlying natural and social orders, as the "way of Heaven" (tiāndào) or universal laws governing phenomena, distinct from but encompassing human-derived methods.[24][26] This polysemous layering—from tangible routes to transcendent principles—reflects cultural emphases on dynamic traversal over static ontology, with semantic cohesion evident in Daoist texts where core concepts cluster around harmonious, processual "ways."[25] The term's adaptability across domains underscores its role as a pivotal, undefined pivot in ancient thought, resisting reduction to any single interpretation.[24]Translations Across Languages

The Chinese character 道, representing the philosophical concept of tào or dào, is transliterated differently across romanization systems and languages, often preserving its phonetic approximation while adapting to local scripts and phonological conventions. In Hanyu Pinyin, the official romanization system standardized by the People's Republic of China and adopted internationally by the ISO in 1982, it is rendered as dào, emphasizing the falling tone.[27] In contrast, the Wade-Giles system, dominant in Western sinology from the 19th to mid-20th centuries, transliterates it as t'ao⁴ or simplified to Tao, as seen in early English translations like James Legge's 1891 The Tao Teh King.[28] This shift from Wade-Giles to Pinyin reflects broader efforts to align transliterations with modern Mandarin pronunciation, though Tao persists in popular and philosophical discourse for historical continuity.[27] In other East Asian languages within the Sinosphere, 道 retains the same character but adopts local Sino-Xenic pronunciations derived from Middle Chinese. Japanese renders it with on'yomi (Sino-Japanese) readings dō or tō in philosophical and compound contexts, such as Dōkyō for Taoism, and kun'yomi michi for native meanings like "road" or "path," as in martial arts terms like kendō (剣道). Korean uses the Sino-Korean pronunciation do, appearing in terms like Dohak (道學) for Taoist learning. Vietnamese employs đạo, with tonal markers reflecting Chữ Nôm influences, as in Đạo giáo for Taoism, preserving semantic layers of "way" or "doctrine." These variations stem from historical borrowing during the Tang dynasty, when Chinese texts were transmitted, leading to phonological adaptations without altering the character's core ideographic form. In European languages, Tao or Dao functions primarily as a loanword transliteration rather than a direct translation, due to the term's polysemous and context-specific nature in Chinese philosophy, which resists simple equivalence. Early French translations, such as Stanislas Julien's 1842 Latin-influenced rendering of the Daodejing, retained Tao to convey its metaphysical nuance beyond literal "voie" (way).[29] German sinologist Richard Wilhelm's 1911 translation similarly used Tao, glossed as der Weg (the way), prioritizing the original to capture dynamic connotations like process or principle.[30] Spanish and Italian renderings follow suit, with Tao or Dao in academic texts, supplemented by camino or via for explanatory purposes, as in modern editions of Laozi's works.[31] This transliteration preference, evident since 19th-century introductions, underscores translators' recognition that semantic equivalents like "way" or "path" inadequately convey tào's ontological depth, prompting footnotes or capitals (the Way) in English to denote its proper-noun status in Taoism.[32]| Language | Primary Transliteration/Pronunciation | Common Semantic Rendering |

|---|---|---|

| English | Dao / Tao | the Way |

| French | Tao | la Voie |

| German | Tao / Dao | der Weg |

| Spanish | Tao / Dao | el Camino |

| Italian | Tao / Dao | la Via |

Historical Origins

Pre-Qin Contexts

The Chinese character dào (道), denoting "way," "path," or "method," first appears in bronze inscriptions from the Western Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–771 BCE), rather than in earlier Shang oracle bone scripts (c. 1600–1046 BCE).[33] In these inscriptions, dào primarily refers to a literal road or route, often in contexts of travel, guidance, or ritual procession, reflecting its pictophonetic composition combining elements of movement (辵) and a head (首) to signify leading or directing.[34] By the Eastern Zhou period (770–256 BCE), including the Spring and Autumn (770–476 BCE) and Warring States (475–221 BCE) eras, dào extended semantically to encompass moral, ritual, or governing principles, as seen in early texts like the Shijing (Book of Odes, compiled c. 11th–7th centuries BCE).[35] Here, it denotes proper conduct or the ancestral path, such as in odes describing the "way" of virtuous rulers or harmonious social order, prefiguring but distinct from later metaphysical interpretations.[24] Similarly, in the Shangshu (Book of Documents), dào implies the normative method of kingship and statecraft, emphasizing efficacy in administration over abstract cosmology.[36] These pre-philosophical uses grounded dào in practical and observable realities—physical paths evolving into ethical or operational guides—without the ontological depth attributed in Warring States Daoist texts.[1] Scholarly analyses confirm this progression from concrete to extended meanings, with no evidence of cosmic or ineffable connotations prior to the late Zhou innovations.[37]Attribution to Laozi and Early Texts

The Daodejing (also rendered Tao Te Ching), comprising 81 short chapters, serves as the foundational early text systematically expounding the concept of Tao as an ineffable, generative force underlying natural order and human conduct, traditionally ascribed to Laozi, a purported Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE) figure described as an archivist and sage.[3] The text's opening lines declare Tao as "the eternal name" from which the myriad things arise, emphasizing its primacy without direct reference to an author.[38] Traditional attribution originates in Sima Qian's Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian, compiled c. 104 BCE), which portrays Laozi as a reclusive elder who dictated the Daodejing to a border guard named Yin Xi before vanishing westward on a water buffalo, framing him as the doctrine's originator amid Zhou decline.[38] This narrative, drawn from earlier oral traditions and Han-era records, lacks corroborating archaeological or contemporary textual evidence, with scholars noting its hagiographic elements akin to mythic founder legends in other philosophies.[3] Modern scholarship, informed by textual criticism and excavations like the Guodian bamboo slips (c. 300 BCE) containing fragmentary chapters and Mawangdui silk manuscripts (168 BCE) yielding near-complete versions, dates the Daodejing's compilation to the late Warring States period (c. 400–221 BCE), likely as an evolving anthology rather than a single composition.[3] Authorship by a historical Laozi is widely doubted, with consensus viewing him as a legendary or composite persona symbolizing anonymous wisdom traditions, possibly conflating figures like "Lao Dan" mentioned in earlier records; linguistic analysis reveals inconsistencies in style and vocabulary across chapters, suggesting multiple contributors.[39][38] Pre-Daodejing references to Laozi appear in the Zhuangzi (compiled c. 4th–3rd century BCE), which invokes him (as Lao Dan) in dialogues exemplifying Tao-aligned detachment and spontaneity, such as critiques of Confucian ritual, without claiming he authored a specific text.[38] Explicit linkage of the Daodejing to Laozi emerges later in Legalist works like the Han Feizi (c. 280–233 BCE) and syncretic Huainanzi (c. 139 BCE), which cite passages to interpret Tao through statecraft and cosmology, marking the solidification of authorship tradition during early Han synthesis.[38] These attributions reflect retrospective canonization rather than eyewitness accounts, prioritizing philosophical utility over verifiable biography.[3]Development in Warring States Period

During the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), a time of political fragmentation, interstate warfare among seven major states, and the decline of Zhou dynasty authority, the philosophical concept of dao matured amid the "Hundred Schools of Thought," emerging as a critique of rigid social and moral frameworks advocated by Confucians and Mohists.[1] This era's chaos prompted thinkers to reconceptualize dao not merely as a human-constructed path of conduct but as tiandao (heavenly way), an impersonal, natural order governing cosmic processes and human affairs through spontaneity (ziran) rather than deliberate intervention.[1] Early Daoist texts positioned dao as a dynamic structuring force, contrasting with Legalist emphases on coercive state power and Confucian rituals, and influencing later syncretic ideas in statecraft.[1] The Daodejing, attributed to the semi-legendary Laozi (active possibly in the 6th century BCE but with textual compilation dated to the 4th–3rd centuries BCE by scholarly consensus), systematized dao as the undifferentiated origin of the cosmos, described as "eternal" and "nameless," from which "one" emerges to generate multiplicity via processes like wuwei (effortless action).[1][38] This portrayal evolved dao into an ontological principle of unity (yi), birthing duality and the "ten thousand things" (wanwu), as in chapter 42: "The dao gives birth to the one; the one gives birth to two; two gives birth to three; three gives birth to the ten thousand things."[40] Debates persist on exact authorship, with evidence suggesting multiple contributors reflecting Warring States oral traditions, yet the text's emphasis on reverting to simplicity amid turmoil provided a counter-narrative to expansionist militarism.[1] Zhuangzi (c. 369–286 BCE), a historical figure from the state of Song, further elaborated dao in the eponymous Zhuangzi text, whose "Inner Chapters" (1–7) are widely attributed to him and composed around the late 4th century BCE, with later chapters added by disciples up to the 3rd century BCE.[41][42] Here, dao transcends Laozi's abstract mysticism, manifesting as a relativistic, transformative continuum that accommodates all perspectives and changes, accessed through "mindless wandering" (you) and skepticism of fixed categories, as in parables like the "butterfly dream" illustrating fluid identity.[41] This development integrated dao with practical ethics, promoting adaptability in a fractured world, while critiquing anthropocentric views; the text's compilation by editors like Guo Xiang (3rd century CE) preserved diverse strands, including anarchistic and syncretic elements.[41] By the period's end, dao's conceptualization had diversified, influencing figures like Shen Dao (fl. 3rd century BCE), who infused it with fatalistic undertones for governance, prefiguring Huang-Lao syncretism under the Qin (221–206 BCE).[1] Archaeological finds, such as Mawangdui silk manuscripts (c. 168 BCE but reflecting Warring States variants), confirm textual fluidity, with dao consistently framed as a holistic "oneness" enabling harmony amid multiplicity.[40] This evolution underscored dao's resilience as a first-order reality, empirically rooted in observations of natural cycles rather than imposed ideologies.[1]Interpretations in Chinese Philosophical Traditions

In Taoism (Daoism)

In philosophical Daoism, the Dao constitutes the foundational principle governing the natural order of the universe, serving as a dynamic structure of possibilities that guides the behavior and transformation of all things without coercion.[1] Described in the Dao De Jing—a text compiled around the 4th to 3rd century BCE, traditionally attributed to Laozi—as ineffable and eternal, the Dao transcends verbal articulation: "The Dao that can be spoken is not the constant Dao; the name that can be named is not the constant name."[3] It originates as a formless, limitless source prior to heaven and earth, generating the "ten thousand things" through a process from unity to multiplicity, often metaphorized as a nurturing mother that acts without possession or claim.[3] Key attributes of the Dao include emptiness yielding inexhaustibility, adaptability akin to water's yielding strength, and spontaneity (ziran), rejecting artificial impositions in favor of natural flow.[1] Human alignment with the Dao emphasizes wu wei, or non-assertive action, wherein individuals act effortlessly in harmony with cosmic patterns, as exemplified in the Zhuangzi through skilled practitioners who respond intuitively without premeditated effort.[1] This approach critiques rigid social norms, promoting simplicity and relativism to avoid conflict arising from imposed hierarchies.[1] Religious Daoism, emerging prominently from the 2nd century CE onward, interprets the Dao cosmologically as both "ultimateless" (wuji), an infinite formless void, and "great ultimate" (taiji), the supreme unity from which duality and multiplicity arise, encompassing the cycles of essence (jing), breath (qi), and spirit (shen).[5] Practices such as internal alchemy (neidan) and meditation seek reversion to the precosmic Dao by refining these vital energies, aiming for longevity or transcendence through rituals that synchronize personal vitality with universal transformations.[5] Unlike philosophical emphases on textual reflection, religious traditions incorporate communal rites and deity invocations to embody the Dao's generative power.[5]In Confucianism

In classical Confucianism, dào (Tao), translated as "way" or "path," primarily signifies the moral and normative order governing human conduct and social relations, distinct from a transcendent cosmic force. Confucius employs the term extensively in the Analects, where it appears 88 times, often denoting the proper method of self-cultivation, governance, or ethical leadership aligned with virtues such as rén (humaneness) and lǐ (ritual propriety).[43] For example, in Analects 4.15, Confucius describes his own dào as "an all-pervading unity," emphasizing a coherent ethical framework rooted in reverence and familial devotion rather than mystical insight.[43] This usage frames dào as a practical guide for the junzi (superior person) to navigate human affairs, fostering harmony through role-specific duties like filial piety and righteous rule.[44] The Confucian dào integrates human action with the mandate of Heaven (tiānmìng), portraying it as an achievable standard through diligent practice rather than innate spontaneity. In Analects 7.6, Confucius instructs devotion to the Way while relying on integrity (yì) and humaneness, underscoring self-reform as the means to realize this path.[45] This human-centered orientation extends to governance, as seen in passages where dào functions as a verb meaning "to lead" or "to govern," such as Analects 2.3, which links effective rule to moral suasion over coercion.[43] Unlike abstract universal principles, Confucian dào manifests in concrete social processes, promoting equilibrium in relationships as articulated in the Book of Rites: no harmony exists without diverse yet ordered elements, akin to music requiring multiple notes.[44] A deeper elaboration appears in the Doctrine of the Mean (Zhōngyōng), attributed to Zisi (c. 483–402 BCE), Confucius's grandson, which defines dào as the "mean" or central course between excess and deficiency, actualized by the noble person in alignment with Heaven's decree.[46] Chapter 2 states: "The Noble Man actualizes the mean," positioning dào as the universal harmony (yōng) that joy and anger express appropriately when attained, reflecting a dynamic balance of inner sincerity (chéng) and external propriety.[46] This text, part of the Confucian canon by the Han dynasty (c. 206 BCE–220 CE), underscores dào as the extension of human nature (xìng) toward cosmic order, achievable through reflective equilibrium rather than withdrawal.[47] Thus, Confucian dào prioritizes ethical rectification in familial, political, and ritual contexts to sustain societal stability.[44]In Legalism and Statecraft

In Legalism, the concept of dao (Tao) was adapted from Daoist cosmology into a pragmatic framework for autocratic governance, emphasizing an impersonal natural order that rulers could harness through coercive mechanisms rather than moral cultivation. Han Feizi (c. 280–233 BCE), the preeminent synthesizer of Legalist thought, portrayed dao as a cosmic principle akin to an unvarying law of nature, which distinguishes order from chaos and underpins the triad of fa (law), shi (positional authority), and shu (administrative techniques).[48] Unlike the metaphysical harmony in Laozi's Daodejing, Han Feizi's dao served statecraft by justifying the ruler's detachment from daily affairs, ensuring stability via standardized laws that mimicked the impartiality of natural processes.[49] This interpretation recast Daoist wu wei (non-action) as a strategic tool for the sovereign, who remains "empty and still" to observe and control ministers without depleting personal resources or inviting manipulation.[50] The ruler delegates execution to officials bound by clear laws and severe punishments, claiming ultimate credit while wielding shi to enforce accountability, thus aligning governance with dao's effortless efficacy.[49] Han Feizi critiqued pure Daoism's withdrawal from politics as impractical amid Warring States chaos (475–221 BCE), instead subordinating dao to realpolitik: laws must be public, uniform, and enforced without favoritism to unify the state under absolute power.[50] This synthesis rejected Confucian benevolence, prioritizing dao-inspired coercion to amass agricultural output, military strength, and territorial expansion.[49] Han Feizi's framework influenced Qin Shi Huang's unification of China in 221 BCE, where dao-guided Legalism enabled rapid centralization through land reforms, conscript labor on projects like the Great Wall (commenced c. 221 BCE), and suppression of rival philosophies via the 213 BCE burning of books.[50] By embodying dao as an objective standard, the system minimized reliance on the ruler's virtue, fostering a bureaucratic empire that valued predictability over ethical norms, though it sowed seeds of rigidity evident in Qin's collapse by 207 BCE.[48][49]Syncretism with Buddhism