Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Deutsche Physik

View on Wikipedia

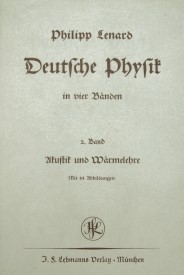

Deutsche Physik (German: [ˈdɔʏtʃə fyˈziːk], lit. "German Physics") or Aryan Physics (German: Arische Physik) was a nationalist movement in the German physics community in the early 1930s which had the support of many eminent physicists in Germany. The term appears in the title of a four-volume physics textbook by Nobel laureate Philipp Lenard in the 1930s.

Deutsche Physik was opposed to the work of Albert Einstein, who was ethnically Jewish, and other modern theoretically based physics, which was disparagingly labeled "Jewish physics" (German: Jüdische Physik).

Origins

[edit]

This movement began as an extension of a German nationalistic movement in the physics community which went back to the start of World War I with Austria's declaration of war on 28 July 1914. On 25 August 1914, during the German Rape of Belgium, German troops used petrol to set fire to the library of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.[1][2][3][4] The burning of the library led to a protest note which was signed by eight distinguished British scientists, namely William Bragg, William Crookes, Alexander Fleming, Horace Lamb, Oliver Lodge, William Ramsay, Lord Rayleigh, and J. J. Thomson. In 1915, this led to a counter-reaction in the form of an "appeal" formulated by Wilhelm Wien and addressed to German physicists and scientific publishers, which was signed by sixteen German physicists, including Arnold Sommerfeld and Johannes Stark. They claimed that German character had been misinterpreted and that attempts made over many years to reach an understanding between the two countries had obviously failed. Therefore, they opposed the use of the English language by German scientific authors, editors of books, and translators.[5] A number of German physicists, including Max Planck and the especially passionate Philipp Lenard, a scientific rival of J. J. Thomson, had then signed further "declarations", so that gradually a "war of the minds"[6] broke out. On the German side it was suggested to avoid an unnecessary use of English language in scientific texts (concerning, e.g., the renaming of German-discovered phenomena with perceived English-derived names, such as "X-ray" instead of "Röntgen ray"). It was stressed, however, that this measure should not be misunderstood as a rejection of British scientific thought, ideas and stimulations.

After the war, the perceived affronts of the Treaty of Versailles kept some of these nationalistic feelings running high, especially in Lenard, who had already complained about England in a small pamphlet at the beginning of the war.[7] When, on 26 January 1920, the former naval cadet Oltwig von Hirschfeld tried to assassinate German Finance minister Matthias Erzberger, Lenard sent Hirschfeld a telegram of congratulation.[8] After the 1922 assassination of politician Walther Rathenau, the government ordered flags flown at half mast on the day of his funeral, but Lenard ignored the order at his institute in Heidelberg. Socialist students organized a demonstration against Lenard, who was taken into protective custody by state prosecutor Hugo Marx.[9]

During the early years of the twentieth century, Albert Einstein's theory of relativity caused bitter controversy within the worldwide physics community. There were many physicists, especially the "old guard", who were suspicious of the intuitive meanings of Einstein's theories. While the response to Einstein was based partly on his concepts being a radical break from earlier theories, there was also an anti-Jewish element to some of the criticism. The leading theoretician of the Deutsche Physik type of movement was Rudolf Tomaschek, who had re-edited the famous physics textbook Grimsehl's Lehrbuch der Physik. In that book, which consists of several volumes, the Lorentz transformation was accepted, as well as the old quantum theory. However, Einstein's interpretation of the Lorentz transformation was not mentioned, and Einstein's name was completely ignored. Many classical physicists resented Einstein's dismissal of the notion of a luminiferous aether, which had been a mainstay of their work for the majority of their productive lives. They were not convinced by the empirical evidence for relativity. They believed that the measurements of the perihelion of Mercury and the null result of the Michelson–Morley experiment might be explained in other ways, and the results of the Eddington eclipse experiment were experimentally problematic enough to be dismissed as meaningless by the more devoted doubters. Many of them were very distinguished experimental physicists, and Lenard was himself a Nobel laureate in Physics.[10]

Under the Third Reich

[edit]

When the Nazis entered the political scene, Lenard quickly attempted to ally himself with them, joining the party at an early stage. With another Nobel laureate in Physics, Johannes Stark, Lenard began a core campaign to label Einstein's relativity as Jewish physics.

Lenard[11] and Stark benefited considerably from this Nazi support. Under the rallying cry that physics should be more "German" and "Aryan", Lenard and Stark embarked on a Nazi-endorsed plan to replace physicists at German universities with "Aryan physicists". By 1935, though, this campaign was superseded by the Nuremberg Laws of 1935. There were no longer any Jewish physics professors in Germany, since under the Nuremberg Laws, Jews were not allowed to work in universities. Stark in particular also tried to install himself as the national authority on "German" physics under the principle of Gleichschaltung (literally, "coordination") applied to other professional disciplines. Under this Nazi-era paradigm, academic disciplines and professional fields followed a strictly linear hierarchy created along ideological lines.

The figureheads of "Aryan physics" met with moderate success, but the support from the Nazi Party was not as great as Lenard and Stark would have preferred. They began to fall from influence after a long period of harassment of quantum physicist Werner Heisenberg, which included getting him labeled a "White Jew" in Das Schwarze Korps. Heisenberg was an extremely eminent physicist, and the Nazis realized that they were better off with him rather than without, however "Jewish" his theory might be in the eyes of Stark and Lenard.[12] In an historic moment, Heisenberg's mother rang Heinrich Himmler's mother and asked her whether she would please tell the SS to give "Werner" a break. After beginning a full character evaluation, which Heisenberg both instigated and passed, Himmler forbade further attack on the physicist. Heisenberg would later employ his "Jewish physics" in the German project to develop nuclear fission for the purposes of nuclear weapons or nuclear energy use. Himmler promised Heisenberg that after Germany won the war, the SS would finance a physics institute to be directed by Heisenberg.[13]

Lenard began to play less and less of a role, and soon Stark ran into even more difficulty, as other scientists and industrialists known for being exceptionally "Aryan" came to the defense of relativity and quantum mechanics. As historian Mark Walker puts it:[14]

... despite his best efforts, in the end his science was not accepted, supported, or used by the Third Reich. Stark spent a great deal of his time during the Third Reich fighting with bureaucrats within the Nazi state. Most of the Nazi leadership either never supported Lenard and Stark, or abandoned them in the course of the Third Reich.

Effect on the German nuclear program

[edit]It is occasionally put forth[15] that there is a great irony in the Nazis' labeling modern physics as "Jewish science", since it was exactly modern physics—and the work of many European exiles—which was used to create the atomic bomb. Even if the German government had not embraced Lenard and Stark's ideas, the German antisemitic agenda was enough by itself to destroy the Jewish scientific community in Germany. Furthermore, the German nuclear weapons program was never pursued with anywhere near the vigor of the Manhattan Project in the United States, and for that reason would likely not have succeeded in any case.[16] The movement did not actually go as far as preventing the nuclear energy scientists from using quantum mechanics and relativity,[17] but the education of young scientists and engineers suffered, not only from the loss of the Jewish scientists but also from political appointments and other interference.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kramer, Alan (2008). Dynamic of Destruction: Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War. Penguin. ISBN 9781846140136.

- ^ Gibson, Craig (30 January 2008). "The culture of destruction in the First World War". Times Literary Supplement. Archived from the original on 6 July 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ LOST MEMORY – LIBRARIES AND ARCHIVES DESTROYED IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY ( Archived 5 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ Theodore Wesley Koch. The University of Louvain and its library. J.M. Dent and Sons, London and Toronto, 1917. Pages 21–23. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 May 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) accessed 18 June 2013 - ^ For the full German text of Wilhelm Wien's appeal see: The Oxford Companion to the History of Modern Science (J. L. Heilbron, ed.), Oxford University Press, New York 2003, p. 419.

- ^ Stephan L. Wolff: Physiker im Krieg der Geister, Zentrum für Wissenschafts- und Technikgeschichte, München 2001, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). - ^ Philipp Lenard, England und Deutschland zur Zeit des großen Krieges – Geschrieben Mitte August 1914, publiziert im Winter 1914, Heidelberg.

- ^ Heinz Eisgruber: Völkische und deutsch-nationale Führer, 1925.

- ^ Der Fall Philipp Lenard – Mensch und "Politiker", Physikalische Blätter 23, No. 6, 262–267 (1967).

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1905". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 8 October 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- ^ Philipp Lenard: Ideelle Kontinentalsperre, München 1940.

- ^ Walker, Mark (1 January 1989). "National Socialism and German Physics". Journal of Contemporary History. 24 (1): 63–89. doi:10.1177/002200948902400103. ISSN 0022-0094.

- ^ Padfield, Peter (1990), Himmler, New York: Henry Holt.

- ^ Walker, Mark (11 November 2013). Nazi Science: Myth, Truth, and the German Atomic Bomb. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4899-6074-0.

- ^ Einstein: His Life and Universe. Chapter 21: The Bomb

- ^ German Nuclear Weapons

- ^ Jeremy Bernstein, Hitler's Uranium Club, the Secret Recordings at Farm Hall, 2001, Springer-Verlag

Further literature

[edit]- Ball, Philip, Serving the Reich: The Struggle for the Soul of Physics Under Hitler (University of Chicago Press, 2014).

- Beyerchen, Alan, Scientists under Hitler: Politics and the physics community in the Third Reich (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977).

- Hentschel, Klaus, ed. Physics and National Socialism: An anthology of primary sources (Basel: Birkhaeuser, 1996).

- Philipp Lenard: Wissenschaftliche Abhandlungen Band IV. Herausgegeben und kritisch kommentiert von Charlotte Schönbeck. [Posthumously, German Language.] Berlin: GNT-Verlag, 2003. ISBN 978-3-928186-35-3. Introduction, Content.

- Walker, Mark, Nazi science: Myth, truth, and the German atomic bomb (New York: HarperCollins, 1995).

External links

[edit] Works related to The Bad Nauheim Debate at Wikisource

Works related to The Bad Nauheim Debate at Wikisource

Deutsche Physik

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Ideological Foundations

Core Principles of Aryan Physics

Aryan Physics, synonymous with Deutsche Physik, maintained that scientific insight arises from racial predispositions, particularly the innate capacity of Nordic or Aryan peoples to probe reality through intuitive and sensory means. Philipp Lenard articulated this in his 1935 foreword to German Physics, declaring that "science is determined by race or by blood" and crediting Nordic types as the originators of true scientific research, dismissing claims of international science as fallacious when non-Nordic contributions stemmed only from partial racial admixture.[5] This racial determinism framed physics as an expression of inherited spiritual differences tied to physical constitution, with Aryan genius enabling foundational discoveries absent in other groups.[6] Central to its methodology was a commitment to empirical observation of perceptible phenomena, favoring direct sensory engagement with inanimate material processes for their simplicity and uniformity over speculative abstraction. Lenard defined physics as the study of "the totality of nature, or the world, as far as it is perceptible to us," prioritizing experimental verification rooted in practical action—the archetype of the tatmensch, or "man of action"—over mathematical models detached from tangible evidence.[6][7] Proponents invoked historical Aryan exemplars such as Newton, Galileo, and Faraday, whose intuitive leadership mirrored the action-oriented ethos of National Socialism, to underscore the compatibility of empirical rigor with völkisch heritage.[7] The ideology sharply critiqued modern theoretical physics, particularly relativity and quantum mechanics, as products of a "all-corrupting foreign spirit" that promoted arrogant delusions of mastering nature through ungrounded formalism.[6] Lenard and allies like Johannes Stark rejected these developments as alien to Aryan methods, advocating instead for a purified physics aligned with racial intuition and sensory realism, free from what they viewed as racially incompatible influences.[7] This stance positioned Deutsche Physik as a restoration of authentic, blood-bound scientific tradition against perceived dilutions in interwar academia.[5]Racial and Philosophical Critiques of Modern Theoretical Physics

Proponents of Deutsche Physik racially critiqued modern theoretical physics by associating key developments, such as Albert Einstein's theory of relativity, with Jewish scientists, labeling it "Jewish physics" (Judenphysik) unfit for Aryan scholars. Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark, both Nobel laureates, contended that relativity's abstract formalism stemmed from racial characteristics incompatible with German empirical traditions.[1][8] This view positioned Einstein's work as an alien intrusion, dismissing its validity on ethnic grounds rather than empirical refutation, as evidenced by Lenard's public attacks following the 1919 solar eclipse confirmation of general relativity.[8] Philosophically, critics argued that relativity and quantum mechanics undermined classical causality and intuitive realism, favoring mathematical speculation over sensory experimentation central to figures like Heinrich Hertz. Lenard emphasized physics as a heroic, hands-on enterprise rooted in direct observation, decrying Einstein's "hyper-theoretical and hyper-mathematical approach" as a destructive influence detached from physical reality.[8] Stark echoed this in his 1930 book Die aktuelle Krise in der deutschen Physik, portraying relativity as dogmatic propaganda that eroded the foundational role of experiment in favor of ungrounded theory.[9] Both rejected quantum theory's probabilistic elements as violating deterministic principles, aligning Deutsche Physik with a worldview prioritizing tangible, causal mechanisms over probabilistic abstractions.[1] These critiques intertwined race and philosophy, positing Aryan intellect as inherently suited to concrete, world-affirming science while portraying Jewish contributions as corrosive and overly intellectualized. Lenard's two-volume Deutsche Physik (1936–1937) exemplified this by advocating a return to pre-relativistic models, grounded in German experimental heritage, and explicitly excluding theoretical innovations from non-Aryan sources.[10] Stark's administrative efforts reinforced this, targeting theorists as "white Jews" regardless of ethnicity, to purge institutions of modern physics' perceived philosophical excesses.[1] Despite such rhetoric, these positions failed to produce viable alternatives, as mainstream German physicists, including Werner Heisenberg, continued quantum research amid political pressure.[7]Historical Origins

Pre-Nazi Scientific Debates

In the aftermath of World War I and the 1919 solar eclipse observations confirming the deflection of light by gravity, as predicted by Einstein's general theory of relativity, a wave of opposition emerged within the German physics community against the theory's rapid acceptance and Einstein's rising prominence. This period in the Weimar Republic saw tensions between traditional experimental physicists and proponents of modern theoretical approaches, with critics arguing that relativity prioritized abstract mathematics over empirical verification and common sense. Philipp Lenard, recipient of the 1905 Nobel Prize for his work on cathode rays, began voicing criticisms of relativity as early as 1918, contending that it erroneously rejected the luminiferous ether and relied on fictitious gravitational fields devoid of physical reality.[10][8] These debates escalated in 1920, marked by public confrontations and organized campaigns. On August 24, 1920, Paul Weyland, purporting to represent a group called the "Working Society of German Scientists for the Preservation of Pure Science," convened a rally at the Berlin Philharmonic Hall, where speakers like Ernst Gehrcke denounced relativity as a form of "scientific mass hypnosis" promoted by sensationalist media and international influences. Shortly thereafter, on September 23, 1920, at the Society of German Natural Scientists and Physicians meeting in Bad Nauheim, Lenard directly challenged Einstein in a heated debate, accusing the theory of undermining established experimental foundations. Johannes Stark, the 1919 Nobel laureate for the Doppler effect in canal rays, echoed these sentiments, criticizing relativity for its abstruse mathematical formalism that neglected tangible experimental reality in favor of speculative constructs.[10][1] Underlying these methodological disputes was a growing nationalist undercurrent, with figures like Lenard and Stark advocating for a physics aligned with German experimental traditions—characterized by hands-on inquiry and intuitive realism—over what they perceived as overly theoretical, "degenerate" innovations. By 1924, Lenard and Stark co-authored an article titled "The Hitler Spirit and Science," linking their scientific critiques to broader cultural and racial preservation efforts, though such explicit ideological fusion predated the Nazi seizure of power in 1933. These pre-Nazi exchanges, while ostensibly rooted in scientific methodology, increasingly incorporated personal and ethnic animus against Einstein, foreshadowing the racialized framework of later movements while highlighting genuine concerns among experimentalists about the shift toward mathematized theory in physics.[1][8]Rise During the Weimar Republic

The opposition to Albert Einstein's theory of relativity, which gained widespread acclaim following the 1919 Eddington solar eclipse expedition confirming general relativity predictions, intensified in Germany during the early Weimar Republic amid nationalist backlash against perceived foreign and Jewish influences in science. Philipp Lenard, recipient of the 1905 Nobel Prize in Physics for cathode ray research, escalated his longstanding critiques of relativity—initially technical objections voiced as early as 1910—by incorporating explicit racial elements in the 1920s, portraying theoretical physics as a destructive Jewish import undermining German experimental traditions.[11][1] In August 1920, an antirelativity rally convened in Berlin's large auditorium, drawing hundreds and signaling organized resistance; this event, coupled with Lenard's public mockery of Einstein during debates, marked the public genesis of sustained campaigns against "Jewish physics."[10][12] The September 1920 confrontation at Bad Nauheim between Lenard and Einstein further exemplified the rift, with Lenard challenging relativity's foundational assumptions on empirical grounds.[13] Johannes Stark, awarded the 1919 Nobel Prize for the electric deflection of spectral lines (Stark effect), aligned with Lenard in rejecting both relativity and emerging quantum mechanics, advocating instead for a "German physics" rooted in classical experimentalism over abstract mathematics.[1][2] Throughout the decade, Lenard and Stark's marginalization within mainstream physics societies fueled their efforts; hundreds of pamphlets and articles proliferated, self-assuredly claiming to refute relativity and linking its proponents to cultural modernism decried as un-German.[14][15] These Weimar-era assaults, though lacking institutional dominance, cultivated a network of like-minded physicists and laid ideological foundations for later National Socialist integration, as Lenard and Stark positioned their views against the Weimar scientific establishment's embrace of theoretical innovations.[16][17]Key Proponents and Institutions

Philipp Lenard and Experimental Tradition

Philipp Lenard, born on June 7, 1862, in Pozsony (now Bratislava), pursued studies in physics at universities including Budapest, Vienna, Berlin, and Heidelberg, earning his Ph.D. from Heidelberg in 1886 under supervisors such as Bunsen and Helmholtz.[18] His early experimental research on cathode rays began in 1888 at Heidelberg and advanced significantly during 1892–1894 while working with Heinrich Hertz at [Bonn](/page/Bon n), where he developed the "Lenard window" using thin aluminum foil to allow rays to exit vacuum tubes into air, revealing their penetration depths of about 1 decimeter in air and several meters in vacuum.[18] This work earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1905 for demonstrating the particulate nature of cathode rays and their properties, building on Hertz's discoveries.[18] As a dedicated experimentalist influenced by Hertz, Lenard prioritized empirical methods grounded in direct observation over abstract theorizing, viewing sensory-based experimentation as the core of reliable physics.[18] In his multi-volume Deutsche Physik (Volume 1 published in 1936, subsequent volumes in 1937), he advocated for a physics rooted in the observable material world, emphasizing sensory perception to gather data on inanimate matter for its uniformity and simplicity, and crediting the experimental legacies of German physicists with unique insight into natural laws.[19][19] Lenard critiqued modern theoretical physics, particularly Einstein's relativity, as detached from experimental verification and reliant on mathematical constructs that ignored physical reality and common sense.[18] This opposition culminated in a public debate with Einstein on September 23, 1920, at the Society of German Natural Scientists and Physicians meeting in Bad Nauheim, where Lenard challenged the foundational assumptions of relativity as ungrounded in empirical tradition.[20] He positioned Deutsche Physik as a return to intuitive, sensory-driven methods exemplified by figures like Hertz, rejecting what he deemed foreign-influenced abstractions that corrupted pure natural science.[19][19]Johannes Stark and Administrative Influence

Johannes Stark, awarded the 1919 Nobel Prize in Physics for discovering the Doppler effect in canal rays and the splitting of spectral lines in electric fields, gained prominent administrative authority in German physics after the Nazi regime's rise in 1933.[21] As a vocal proponent of Deutsche Physik, Stark leveraged these roles to advance nationalist scientific policies, prioritizing experimental traditions over theoretical frameworks deemed incompatible with Aryan ideology.[22] In April 1933, Stark was appointed president of the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt (PTR), Germany's leading metrology and standards institute, succeeding Friedrich Paschen and holding the position until his retirement in 1939.[23] Concurrently, he headed the Notgemeinschaft der Deutschen Wissenschaft, the primary funding body for research, using it to direct resources toward projects aligned with National Socialist goals and away from "Jewish-influenced" theories like relativity.[22][23] These appointments, facilitated by his prior anti-Einstein campaigns and sympathy for Nazi racial doctrines, enabled Stark to influence personnel decisions, including the dismissal of Jewish scientists from PTR and affiliated institutions.[22][1] Stark's administrative influence extended to broader policy efforts, such as advocating for the purge of modern theorists from academia and research bodies, explicitly targeting figures like Albert Einstein whose work he labeled as culturally alien.[22][23] In 1934, he published Nationalsozialismus und Wissenschaft, articulating a vision of science subordinated to ideological purity, which informed his pushes for appointments favoring Deutsche Physik adherents over quantum mechanics proponents.[22] Collaborating with Philipp Lenard, Stark sought to embed these principles in journals, curricula, and funding priorities, though his overreach—evident in failed attempts to discredit Werner Heisenberg—highlighted limits to his sway amid internal scientific resistance.[22][1] By 1936, Stark's public denunciations of theoretical physics as a threat to German science intensified, aligning administrative actions with propaganda campaigns against "degenerate" research.[24]

Supporting Organizations and Publications

Philipp Lenard's Deutsche Physik, a four-volume series published by J.F. Lehmanns Verlag in Munich from 1936 to 1937, constituted the cornerstone publication of the movement. The volumes covered introductory mechanics, acoustics and heat, optics, and electricity, presenting physics through an experimental lens rooted in 19th-century classical traditions while rejecting modern theoretical frameworks. Intended as textbooks for German universities, these works explicitly critiqued relativity and quantum mechanics as abstract and un-German, advocating instead for intuitive, sensory-based understanding derived from heroic Aryan scientists like Galileo and Newton.[25][3] Johannes Stark contributed polemical writings, including articles in journals and pamphlets such as his 1930 Die gegenwärtige Krisis in der deutschen Physik, which lambasted theoretical physics as a Jewish degeneration of true German experimental science. These publications disseminated Deutsche Physik ideology beyond academic circles, influencing public and policy discourse on scientific purity.[26] Key supporting organizations leveraged Nazi administrative power to institutionalize the movement. The Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt (PTR), with Stark as president from April 1933 to 1939, shifted priorities toward applied experimental physics aligned with Deutsche Physik, sidelining theoretical research and using its metrology standards to challenge relativity-based validations.[23] As president of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) from 1934 to 1936, Stark reoriented funding to favor projects embodying "Aryan" experimentalism, denying grants to proponents of modern theories and enforcing ideological conformity in research proposals. This control over national science funding amplified Deutsche Physik's reach, enabling purges and appointments that embedded its principles in German academia.[27][23]Implementation in Nazi Germany

Policy Integration with National Socialism

Deutsche Physik aligned with National Socialist ideology by framing experimental, intuitive physics as an expression of Aryan racial characteristics, contrasting it with theoretical approaches deemed abstract and culturally alien. Proponents Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark explicitly linked their movement to Nazi racial purity and anti-Semitism, portraying modern physics innovations like relativity as "Jewish" corruptions incompatible with German heroic traditions.[28] This ideological framing facilitated policy integration, as Nazi authorities viewed Deutsche Physik as a tool for aligning scientific practice with völkisch worldview, emphasizing sensory experience and national self-reliance over internationalist or mathematical abstraction.[8] Following the Nazi assumption of power on January 30, 1933, Lenard, who had endorsed Hitler in the 1920s, emerged as a symbolic leader, receiving the Goethe Medal from the regime in 1935 for embodying German scientific spirit.[8][28] Stark, similarly an early Nazi Party member, leveraged administrative roles to enforce these views; appointed president of the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt (PTR) in April 1933, he purged Jewish scientists and prioritized appointments based on racial and ideological conformity, arguing that scientific leadership required "pure-blooded Germans."[21][29] Stark further influenced policy through his position on the Reich Research Council from 1936, advocating for the suppression of "degenerate" theories in funding and publications.[30] In education, Deutsche Physik principles permeated university curricula and textbooks under Gleichschaltung directives, with Lenard authoring works like Vierteljahrschrift für angewandte Physik to propagate anti-relativistic pedagogy from 1936 onward.[28] Nazi education ministry guidelines, enforced post-1933, mandated racial framing in sciences, leading to the exclusion of Einstein's works from syllabi and the elevation of classical German experimentalists like Hertz and Lenard himself.[31] However, full policy dominance was constrained by practical wartime needs; while ideological purges affected approximately 15% of physicists by 1938, key research programs like uranium fission proceeded under non-Deutsche Physik adherents due to their technical indispensability.[32] This partial integration reflected Nazi prioritization of ideological conformity where feasible, but utility over dogma in high-stakes applied science.[33]Academic Purges and Appointments

The enactment of the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service on April 7, 1933, initiated widespread dismissals of Jewish academics, including physicists, from German universities and research institutions, with approximately 25% of the nation's physicists affected due to their Jewish ancestry.[34] This racial purge, justified under Nazi ideology, removed figures such as James Franck and many others, creating vacancies that proponents of Deutsche Physik sought to fill with advocates of intuitive, experimental approaches over theoretical innovations like relativity.[32] Johannes Stark, a key Deutsche Physik advocate, was appointed president of the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt (PTR) on April 1, 1933, succeeding Friedrich Paschen, enabling him to reorganize the institute along ideological lines by dismissing staff perceived as supporters of "Jewish physics" and prioritizing experimental traditionalism.[23] In this role, Stark targeted theoretical physicists, including attempts to undermine Aryan proponents like Werner Heisenberg, whom he derisively labeled a "white Jew" for defending quantum mechanics, though Heisenberg retained his Leipzig professorship amid internal opposition.[1] Philipp Lenard, similarly influential as director of the physics institute at Heidelberg University, endorsed these efforts and pushed for appointments favoring sensory-based methodologies, criticizing university chairs held by modern theorists as corrupted by alien influences.[35] By 1936, Deutsche Physik sympathizers gained leverage in the Reich Ministry of Science, Education, and Culture, granting oversight of professorial appointments and enabling the blocking of candidates associated with positivism or abstraction, though resistance from figures like Max Planck limited wholesale replacement in elite universities.[7] Stark and Lenard collaborated to denounce theoretical physics as degenerate, advocating purges beyond racial criteria to enforce a "German" physics rooted in empirical intuition, resulting in harassment, denied promotions, and selective hiring of aligned experimentalists, such as in provincial institutions where their influence proved stronger.[26] Despite these actions, the movement's purges failed to eradicate theoretical research entirely, as wartime priorities compelled retention of skilled Aryan theorists.[24]Scientific Claims and Methodological Disputes

Specific Objections to Relativity

Proponents of Deutsche Physik, including Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark, objected to Einstein's theory of relativity primarily for its perceived detachment from empirical foundations and intuitive physical understanding, favoring instead a physics rooted in direct experimentation and sensory realism.[8][1] They contended that relativity's heavy reliance on abstract mathematics obscured physical truth, promoting what they termed a "hyper-theoretical" approach that prioritized formalism over verifiable phenomena.[8][36] Lenard specifically criticized special relativity for abolishing the luminiferous ether, which he regarded as essential for explaining electromagnetic wave propagation, arguing that Einstein's unification of space and time eliminated a material medium necessary for causal transmission.[12] In the 1920 Bad Nauheim debate with Einstein, Lenard challenged the relativity principle by proposing thought experiments, such as accelerating the Earth, to demonstrate absolute motion and simultaneity, which he claimed relativity unphysically prohibited.[13] He further asserted in his 1918 writings that relativity employed rhetorical "tactics" to evade contradictory experimental evidence, such as those from classical optics, and dismissed its predictions as untestable or fraudulent in core claims.[10] Regarding general relativity, both Lenard and Stark alleged inconsistencies, including the theory's allowance for superluminal velocities in certain derivations, which they viewed as violating causality and empirical limits on signal speeds.[1] Stark, in his 1930s publications like Die aktuelle Krise in der deutschen Physik, decried general relativity as dogmatic propaganda that exalted theoretical speculation over practical advancements, insisting it hindered genuine progress by rejecting absolute reference frames evident in laboratory settings.[9] These critics maintained that relativity's equivalence principle led to absurdities, such as equating gravitational and inertial effects without sufficient experimental isolation, prioritizing instead "Aryan" methods grounded in tangible, repeatable demonstrations.[37][36]Rejections of Quantum Mechanics and Positivism

Proponents of Deutsche Physik, led by Nobel laureates Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark, vehemently opposed quantum mechanics for its abandonment of classical causality and determinism in favor of probabilistic outcomes and abstract mathematical formalism. Lenard, in his multi-volume work Deutsche Physik published between 1936 and 1937, argued that quantum theory's emphasis on statistical predictions over precise causal mechanisms represented a degeneration from empirical, sensory-based physics rooted in Germanic experimental traditions.[38] Stark echoed this, decrying the theory's "hyper-theoretical" nature, which he believed obscured intuitive understanding of natural phenomena and prioritized unvisualizable entities like wave functions over observable effects.[8] This rejection extended to the Copenhagen interpretation, developed by Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg in the mid-1920s, which Lenard and Stark saw as promoting acausality and indeterminism, incompatible with their advocacy for a physics grounded in strict cause-and-effect relations verifiable through direct experimentation.[39] By 1933, Stark had publicly attacked Heisenberg's matrix mechanics—formulated in 1925—as emblematic of this shift, labeling it a departure from "real" physics that favored mathematical gamesmanship over practical, reality-anchored inquiry.[40] The movement's critique also targeted positivism's influence on quantum mechanics, particularly its restriction of scientific discourse to empirically verifiable observables while dismissing deeper causal realities as metaphysical speculation.[41] Lenard contended that such positivist constraints, akin to those in Bohr's complementarity principle introduced in 1927, eroded the foundational realism of physics by denying the existence of underlying deterministic processes, which he insisted could be intuited from everyday sensory experience and classical mechanics. Stark reinforced this by demanding a return to "Aryan physics" that preserved causal chains and rejected positivist agnosticism toward unobservables, viewing it as a corrosive ideology that fragmented the unity of physical law. These objections, framed as a defense of empirical integrity against theoretical excess, underpinned Deutsche Physik's broader campaign to purge modern physics from German academia.Advocacy for Intuitive and Sensory-Based Physics

Advocates of Deutsche Physik promoted a physics methodology emphasizing Anschaulichkeit, an intuitive and visually comprehensible grasp of phenomena rooted in direct experimental observation and sensory perception, in opposition to the abstract mathematical frameworks of relativity and quantum mechanics.[42] This approach posited that genuine physical understanding emerges from empirical data and mental imagery aligned with everyday sensory experience, rather than detached theoretical constructs.[38] Philipp Lenard articulated this in his four-volume Deutsche Physik (1936–1937), where he reframed classical physics through descriptive methods accessible via intuitive mental pictures and sensory-based experiments, arguing that advanced mathematics veiled rather than revealed natural truths.[19][8] Lenard contended that physics should prioritize "respect for facts and aptitude for exact observation," decrying hyper-theoretical models as pernicious influences that prioritized formalism over practical experimentation.[43] He specifically criticized relativity for violating "intuitively obvious pictures of nature," insisting on methodologies that harmonized with perceptual immediacy.[42] Johannes Stark reinforced this stance by lambasting the "mathematization" of physics as a departure from its empirical core, favoring concrete, sense-oriented investigations that experimentalists could intuitively validate.[1] Stark viewed abstract theories as overly complex and detached from observable reality, aligning Deutsche Physik with a tradition of direct sensory engagement exemplified in 19th-century classical mechanics.[11] Both Lenard and Stark maintained that such intuitive, sensory-grounded physics reflected a national predisposition for tangible, fact-driven inquiry, dismissing mathematical abstraction as incompatible with truthful scientific progress.[1][8]Internal Opposition and Community Dynamics

Resistance from Mainstream Physicists

Mainstream German physicists, adhering to empirical and theoretical standards, resisted the Deutsche Physik movement's efforts to discredit relativity and quantum mechanics as ideologically tainted, prioritizing scientific merit over racial or nationalistic criteria. This opposition included public lectures, collective petitions, and continued advocacy for mathematical formalism against proponents' emphasis on sensory intuition. Resistance was often cautious, balancing preservation of research programs with avoidance of direct confrontation that could invite reprisals, yet it contributed to limiting the movement's dominance within academic institutions.[1] Max von Laue, a 1914 Nobel laureate for X-ray diffraction, exemplified overt defiance. In March 1933, he protested the Prussian Academy of Sciences' endorsement of Einstein's resignation amid anti-Semitic purges, demanding a formal discussion that was ultimately overruled. Later, on September 18, 1933, von Laue delivered a presidential address to the German Physical Society likening the regime's rejection of relativity to the Inquisition's suppression of Galileo, concluding with the defiant phrase "And yet it moves!" to underscore the theory's enduring validity; the audience applauded despite the risks. He further supported dismissed Jewish colleagues, such as visiting editor Arnold Berliner from 1935 until his death in 1942.[44][1] Collective actions amplified individual stands. In 1931, von Laue and Walther Nernst publicly rebutted a anti-Einstein manifesto edited by Philipp Lenard. By 1937, Werner Heisenberg, Max Wien, and Hans Geiger circulated a petition signed by 75 professors, calling for cessation of attacks on theoretical physics to protect Germany's international scientific standing. Such efforts highlighted the impracticality of banning core concepts like relativistic mass increase, which underpinned practical applications.[1] Personal perils underscored the stakes. Heisenberg, targeted for incorporating relativity in Leipzig lectures, endured a late-1930s denunciation as a "white Jew" in Nazi newspapers, yet Heinrich Himmler's intervention—prompted by familial ties—permitted continued teaching of the concepts, albeit without naming Einstein. These resistances, though frustrating and incomplete, sustained modern physics' foothold against ideological purges, influencing community dynamics into the wartime period.[45][1]Heisenberg's Defense of Theoretical Approaches

Werner Heisenberg, a leading proponent of quantum mechanics, faced direct attacks from Deutsche Physik advocates such as Johannes Stark, who in 1936 labeled him a "white Jew" in the SS publication Das Schwarze Korps for promoting allegedly Jewish-influenced theoretical physics.[46][47] In response, Heisenberg defended abstract theoretical methods by arguing that they formed the foundation of advanced German scientific achievements, emphasizing their development by Aryan physicists including himself, Max Born (despite Born's Jewish heritage), and Pascual Jordan.[1] Heisenberg's key rebuttal appeared in a 1936 response to an article in the Völkischer Beobachter titled "Deutsche und Jüdische Physik," where he contended that theoretical physics, though mathematically abstract, was essential for interpreting experimental data and predicting technological breakthroughs, such as improvements in spectroscopy and electronics derived from quantum theory.[48] He illustrated this by noting how James Clerk Maxwell's electromagnetic theory—initially abstract and non-intuitive—enabled practical inventions like radio communication, warning that dismissing such approaches would cripple Germany's industrial and military capabilities.[1] To counter the Deutsche Physik emphasis on sensory intuition and rejection of mathematical formalism, Heisenberg advocated a balanced methodology integrating rigorous theory with empiricism, asserting in lectures and writings that quantum mechanics' probabilistic framework, while counterintuitive, accurately described subatomic phenomena verified by experiments like the Compton effect and blackbody radiation.[40] He critiqued excessive positivism in interpretations of quantum theory to align with Nazi preferences for "realistic" causality but maintained that the theory's mathematical structure was indispensable for progress, as evidenced by its role in developing semiconductors and isotopes.[1] By late 1936, Heisenberg rallied support from fellow physicists, including a petition underscoring theoretical physics' necessity for national strength, which helped secure his position at Leipzig University after temporary restrictions.[49] His defenses extended to private interventions, such as appeals to SS leaders highlighting how theoretical insights drove wartime applications in optics and nuclear research, thereby preserving mainstream physics against ideological purges.[50] Despite these efforts, Heisenberg navigated persecution risks, including Gestapo surveillance, by framing theoretical abstraction as compatible with Germanic intellectual tradition rather than foreign import.[47]Impact on German Wartime Science

Disruptions to the Nuclear Research Program

The rejection of modern theoretical physics by Deutsche Physik proponents, who dismissed quantum mechanics and relativity as "Jewish" influences incompatible with intuitive Aryan methods, undermined the conceptual foundations of Germany's nuclear research. The Uranverein, initiated on 11 April 1939 under the Reich Research Council to investigate uranium fission for energy and potential weapons, relied heavily on quantum theory to model neutron behavior and chain reactions—precisely the domains derided by figures like Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark. This ideological stance fostered skepticism among Nazi officials toward the program's theoretical underpinnings, contributing to fragmented coordination and limited resource allocation despite Germany's early lead in fission discovery by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann on 17 December 1938.[51][52] Werner Heisenberg, appointed to lead key theoretical aspects of the Uranverein, faced direct assaults from Stark, who leveraged his position as president of the Reich Physical-Technical Institute until 1939 and Nazi Party affiliations to denounce Heisenberg's S-matrix theory and quantum work as degenerate. In 1937, Stark and allies published condemnations in the SS newspaper Das Schwarze Korps, labeling Heisenberg a "white Jew" and urging his removal from influence, which prompted Gestapo surveillance and threats to his career. Although Heisenberg retained his Kaiser Wilhelm Institute directorship through interventions—including his mother's 1938 appeal to Heinrich Himmler's mother—these attacks diverted his focus, eroded community cohesion, and amplified doubts about the viability of "theoretical" nuclear pursuits among regime hardliners.[53][54] By 1942, these disruptions manifested in the program's restructuring under Armaments Minister Albert Speer, who curtailed ambitions for a fission bomb in favor of reactor development and conventional weaponry, citing uncertain timelines and high costs amid ideological wariness of unproven "degenerate" science. Experimental efforts, such as the Haigerloch reactor under Heisenberg's guidance, suffered from suboptimal designs—like cube-based uranium configurations over more efficient rods—partly reflecting hesitancy to fully embrace discarded theoretical optimizations. The internal divisions, compounded by Deutsche Physik's influence on personnel decisions and funding priorities, ensured the nuclear initiative remained under-resourced, with total investment estimated at under 10 million Reichsmarks by war's end, far below Allied scales, ultimately stalling any path to a deployable weapon.[55][52]Effects on Broader Physics and Technology Development

The advocacy of Deutsche Physik exacerbated the dismissal and emigration of key physicists, with approximately 25% of Germany's physics workforce—numbering around 1,200 professionals—losing positions by 1938 due to racial and ideological criteria, including eleven past or future Nobel laureates such as Max Born and James Franck.[34] This exodus, peaking after the 1933 Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, decimated centers like the University of Göttingen, where a quarter of the theoretical physics faculty departed, depriving Germany of expertise in quantum mechanics essential for foundational research in electronics and materials science.[56] The movement's rejection of quantum theory as "positivistic" and "Jewish" fostered a climate of intimidation, prompting even non-emigrating physicists like Werner Heisenberg to face public denunciations, which diverted intellectual energy from innovation to ideological defense.[7] In technological domains reliant on modern theoretical physics, such as early solid-state devices and advanced electronics, progress stagnated relative to Allied efforts; Germany's pre-1933 leadership in quantum solid-state research, exemplified by Arnold Sommerfeld's group, fragmented as collaborators like Hans Bethe emigrated in 1933, leaving gaps in understanding electron behavior in solids that hindered wartime applications like improved vacuum tubes or semiconductors.[32] Funding priorities shifted toward "intuitive" experimentalism favored by figures like Philipp Lenard, whose cathode-ray work predated quantum insights but stalled integration with wave mechanics, contributing to delays in high-frequency electronics critical for superior radar or communications systems—Germany's Würzburg radar, operational by 1940, lagged behind British cavity magnetron developments in precision and power.[33] Conversely, fields insulated from pure theoretical disputes, including rocketry and aeronautics, advanced unimpeded by Deutsche Physik orthodoxy, as engineering pragmatism under military oversight prevailed; Wernher von Braun's Aggregate-4 (V-2) program achieved its first successful launch on October 3, 1942, leveraging classical mechanics without quantum dependencies.[57] Jet engine prototypes like the Heinkel He 178, flown on August 27, 1939, similarly progressed via empirical aerodynamics. Yet, the broader ideological overlay isolated German physicists from global exchanges, amplifying inefficiencies: wartime resource allocation favored ideologically aligned projects, and altered university curricula omitted relativity and quantum principles, impairing the training of post-1940 cohorts and sowing seeds for long-term competitive disadvantages in physics-driven technologies.[7][56]Post-War Assessments and Legacy

Immediate Aftermath and Denazification

Following the unconditional surrender of Nazi Germany on May 8, 1945, the Deutsche Physik movement, sustained by state patronage and ideological enforcement, collapsed without institutional backing or political relevance. Its core tenets, emphasizing intuitive experimentalism over theoretical frameworks deemed "Jewish," were swiftly discredited amid the broader repudiation of Nazi pseudoscience, as Allied occupation authorities prioritized restoring scientific integrity aligned with international standards. German physics departments, previously pressured to purge relativity and quantum mechanics from curricula, began reintegrating these fields, with surviving mainstream physicists like Werner Heisenberg leveraging the movement's evident failures—such as its hindrance to wartime technologies—to distance the discipline from Nazi associations.[7] Denazification proceedings, initiated by Allied Control Council Law No. 10 in late 1945, targeted Deutsche Physik advocates for their roles in politicizing science and advancing racialized ideologies. Philipp Lenard, the movement's leading ideologue and Nobel laureate, was arrested in 1945 due to his prominent Nazi affiliations, including authorship of anti-relativity tracts and advisory roles to the regime; however, at age 82, he was released owing to frail health and died on May 20, 1947, in obscurity at his estate in Messelhausen.[8] Johannes Stark, another Nobel winner and key enforcer who headed the Reich Research Council from 1933 to 1939, faced harsher scrutiny; in 1947, a Bavarian denazification court classified him as a "major offender" for ideological agitation and abuse of scientific authority, sentencing him to four years' imprisonment and fines totaling 100,000 Reichsmarks, though the prison term was not fully executed due to appeals and his age.[22] The process exposed how Deutsche Physik had marginalized talent and delayed progress, yet it also served as a scapegoat for the wider German physics community's accommodations under Nazism; proponents' marginal pre-war achievements and post-hoc irrelevance underscored the movement's reliance on coercion rather than empirical merit, facilitating a pivot to positivism and international collaboration by 1949. Denazification questionnaires and tribunals suspended or dismissed dozens of affiliated academics from universities and institutes, though incomplete enforcement—amid Cold War pressures—allowed some lesser figures to retain influence in East and West German reconstructions.[4]Historiographical Debates and Modern Re-evaluations

Early post-war historiography often portrayed Deutsche Physik as a primary cause of Germany's scientific stagnation during the Nazi era, with figures like Samuel Goudsmit attributing the failure to develop an atomic bomb to ideological rejection of modern theoretical physics by Aryan physics proponents such as Philipp Lenard and Johannes Stark.[58] This view emphasized how the movement's campaigns against "Jewish physics"—including relativity and quantum mechanics—fostered an environment of censorship and personnel purges, contributing to the exodus of approximately 25% of Germany's physicists by 1933, many of whom were Jewish or politically suspect.[26] However, such accounts have been critiqued for oversimplifying the physics community's resilience, as mainstream institutions like the Kaiser Wilhelm Society continued empirical and theoretical work despite pressures. Alan D. Beyerchen's 1977 study challenged these narratives by documenting Deutsche Physik's limited long-term influence, noting its peak in the mid-1930s through Stark's brief control of bodies like the Reich Research Council and Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt, followed by decline after 1937 due to internal opposition and the regime's pragmatic needs for wartime technology.[58] Beyerchen highlighted acts of resistance, such as Max von Laue's 1933 public defense of theoretical physics at the Würzburg physicists' meeting and the 1935 Haber Memorial Lecture organized by Max Planck, which defied Nazi bans on honoring Jewish scientists.[26] He argued that while ideology affected appointments and morale, German physicists largely pursued modern methods in nuclear research, with failures attributed more to strategic miscalculations—like underestimating critical mass requirements—than wholesale rejection of quantum theory.[59] Modern re-evaluations, informed by declassified sources like the 1945 Farm Hall transcripts of interrogated German scientists, portray Deutsche Physik as a fringe phenomenon exploited postwar to construct narratives of moral resistance and scientific autonomy.[58] Historians now assess its impact as indirect: amplifying emigration losses (e.g., over 2,000 Jewish scientists fled by 1938) and diverting resources to applied projects, but not halting progress in uranium enrichment or reactor experiments under Werner Heisenberg's Uranverein program, which employed relativity-based calculations.[26] Debates continue over whether the movement's marginalization reflects genuine community pushback or regime prioritization of utility over dogma, with some scholars cautioning against understating accommodations, as evidenced by the Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft's 1938 purge of Jewish members and endorsements of Nazi policies.[58] These reassessments underscore Deutsche Physik's role less as a scientific catastrophe than as symptomatic of politicization's corrosive effects on institutional trust and talent retention.References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Translation:The_Bad_Nauheim_Debate