Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

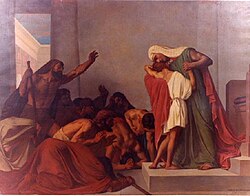

Joseph (Genesis)

View on Wikipedia

Joseph (/ˈdʒoʊzəf, -səf/; Hebrew: יוֹסֵף, romanized: Yōsēp̄, lit. 'He shall add')[2][a] was a dream interpreter and considered an important Hebrew figure in the Bible's Book of Genesis.

Key Information

Joseph was the first of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel, making him Jacob's twelfth named child and eleventh son. He is the founder of the Tribe of Joseph among the Israelites. His story functions as an explanation for Israel's residence in Egypt. He is the favourite son of the patriarch Jacob, and his envious brothers sell him into slavery in Biblical Egypt, where he eventually ends up incarcerated. After correctly interpreting the dreams of Pharaoh, he rises to second-in-command in Egypt and saves Egypt during a famine. Jacob's family travels to Egypt to escape the famine, and it is through him that they are given leave to settle in the Land of Goshen (the eastern part of the Nile Delta).

Scholars hold different opinions about the historical background of the Joseph story, as well as the date and development of its composition.[6] Some scholars suggest that the biblical story of Joseph (Gen 37-50) was a multigenerational work with both early and late components.[7] Others hold that the original Joseph story was a Persian period diaspora novella told from the perspective of Judeans living in Egypt.[8][9]

In Jewish tradition, he is the ancestor of a second Messiah called "Mashiach ben Yosef", who will wage war against the forces of evil alongside Mashiach ben David and die in combat with the enemies of God and Israel.[10] Christian tradition often interprets him as a typological precursor to Jesus, emphasizing his virtue and suffering. In Islam, Joseph (Yusuf) is regarded as a prophet, and the Quran recounts his story with some variations, such as the healing of Jacob’s eyes. The Bahá’í faith also references Joseph metaphorically in relation to recognizing manifestations of God. Beyond religious texts, Joseph’s story has inspired extensive literature, music, theater, and film adaptations, as well as numerous international films and television series retelling the story.

Etymology

[edit]The Bible offers two explanations of the name Yosēf: first, it is compared to the triliteral א־ס־ף (ʾ-s-p), meaning "to gather, remove, take away":[11] "And she conceived, and bore a son; and said, God hath taken away my reproach" (Genesis 30:23);[12] Yosēf is then identified with the similar root יסף (y-s-p), meaning "to add":[13] "And she called his name Joseph; and said, The LORD shall add to me another son." (Genesis 30:24).[14][15]

Biblical narrative

[edit]Birth and family

[edit]Joseph, son of Jacob and Rachel, lived in the land of Canaan with ten half-brothers, one full brother, and at least one half-sister. He was Rachel's firstborn and Jacob's eleventh son. Of all the sons, Joseph was preferred by his father, who gave him a "long coat of many colors".[b] When Joseph was seventeen years old, he shared with his brothers two dreams he had: in the first dream, Joseph and his brothers gathered bundles of grain, of which those his brothers gathered, bowed to his own. In the second dream, the Sun (father), the Moon (mother), and eleven stars (brothers) bowed to Joseph himself. These dreams, implying his supremacy, angered his brothers (Genesis 37:1–11) and made the brothers plot his demise.

-

Joseph's dream of grain

-

Joseph's dream of stars

Plot against Joseph

[edit]

In Genesis 37, Vayeshev, Joseph's half-brothers were envious of him. Most of them plotted to kill him in Dothan, except Reuben,[16][17] who suggested they throw Joseph into an empty cistern; he intended to rescue Joseph himself later. Unaware of this plan to rescue Joseph, the others agreed with Reuben.[c] Upon imprisoning Joseph, the brothers saw a camel caravan carrying spices and perfumes to Egypt, and sold Joseph to these merchants.[d] The guilty brothers painted goat's blood on Joseph's coat and showed it to Jacob, who therefore believed Joseph had died.

Potiphar's house

[edit]In Genesis 39, Vayeshev, Joseph was sold to Potiphar, the captain of Pharaoh's guard. Later, Joseph became Potiphar's servant, and subsequently his household's superintendent. Here, Potiphar's wife (later called Zulaykha) tried to seduce Joseph, which he refused. Angered by his running away from her, she made a false accusation of rape so he would be imprisoned.[e]

Joseph in prison

[edit]

The warden put Joseph in charge of the other prisoners and soon afterward Pharaoh's chief cup-bearer and chief baker, who had offended the Pharaoh, were thrown into the prison. Both men had dreams, and Joseph, being able to interpret dreams, asked to hear them.

The cup-bearer's dream was about a vine with three branches that was budding. And as it was budding, its blossoms came out and they produced grapes. The cup-bearer took those grapes and squeezed them into Pharaoh's cup, and placed the cup in Pharaoh's hand. Joseph interpreted this dream as the cup-bearer being restored as cup-bearer to the Pharaoh within three days.

The baker's dream was about three baskets full of bread for the Pharaoh, and birds were eating the bread out of those baskets. Joseph interpreted this dream as the baker being hanged within three days and having his flesh eaten by birds.

Joseph requested that the cup-bearer mention him to Pharaoh to secure his release from prison, but the cup-bearer, reinstalled in office, forgot Joseph.

After two more years, the Pharaoh dreamt of seven lean cows which devoured seven fat cows; and of seven withered ears of grain which devoured seven fat ears. When the Pharaoh's advisers failed to interpret these dreams, the cup-bearer remembered Joseph. Joseph was then summoned. He interpreted the dream as seven years of abundance followed by seven years of famine and advised the Pharaoh to store surplus grain.

Vizier of Egypt

[edit]

Following the prediction, Joseph became Vizier, under the name of Zaphnath-Paaneah (Hebrew: צָפְנַת פַּעְנֵחַ Ṣāp̄naṯ Paʿnēaḥ),[f][18] and was given Asenath, the daughter of Potipherah, priest of On,[g] to be his wife. During the seven years of abundance, Joseph ensured that the storehouses were full and that all produce was weighed. In the sixth year, Asenath bore two children to Joseph: Manasseh and Ephraim. When the famine came, it was so severe that people from surrounding nations came to Egypt to buy bread. The narrative also indicates that they went straight to Joseph or were directed to him, even by the Pharaoh himself (Genesis 41:37–57). As a last resort, all of the inhabitants of Egypt, less the Egyptian priestly class, sold their properties and later themselves (as slaves) to Joseph for seed; wherefore Joseph set a mandate that, because the people would be sowing and harvesting seed on government property, a fifth of the produce should go to the Pharaoh. This mandate lasted until the days of Moses (Genesis 47:20–31).

Brothers sent to Egypt

[edit]

In the second year of famine,[19] Joseph's half brothers were sent to Egypt to buy goods. When they came to Egypt, they stood before the Vizier but did not recognize him as their brother Joseph, who was now in his late 30s; but Joseph did recognize them and did not speak at all to them in his native tongue of Hebrew.[20] After questioning them, he accused them of being spies. After they mentioned a younger brother at home, the Vizier (Joseph) demanded that he be brought to Egypt as a demonstration of their veracity. This was Joseph's full brother, Benjamin. Joseph placed his brothers in prison for three days. On the third day, he brought them out of prison to reiterate that he wanted their youngest brother brought to Egypt to demonstrate their veracity. The brothers conferred amongst themselves speaking in Hebrew, reflecting on the wrong they had done to Joseph. Joseph understood what they were saying and removed himself from their presence because he was caught in emotion. When he returned, the Vizier took Simeon and bound him as a hostage.[h] Then he had their donkeys prepared with grain and sent the other brothers back to Canaan. Unbeknownst to them, Joseph had also returned their money to their money sacks (Genesis 42:1–28).

The silver cup

[edit]The remaining brothers returned to their father in Canaan, and told him all that had transpired in Egypt. They also discovered that all of their money sacks still had money in them, and they were dismayed. Then they informed their father that the Vizier demanded that Benjamin be brought before him to demonstrate that they were honest men. Jacob became greatly distressed, feeling deprived of successive sons: Joseph, Simeon, and (prospectively) Benjamin. After they had consumed all of the grain that they brought back from Egypt, Jacob told his sons to go back to Egypt for more grain. With Reuben and Judah's persistence, they persuaded their father to let Benjamin join them for fear of Egyptian retribution (Genesis 42:29–43:15).

Upon their return to Egypt, the steward of Joseph's house received the brothers. When they were brought to Joseph's house, they were apprehensive about the returned money in their money sacks. They thought that the missed transaction would somehow be used against them as way to induct them as slaves and to confiscate their possessions. So they immediately informed the steward of what had transpired. The steward put them at ease, telling them not to worry about the money, and brought out their brother Simeon. Then he brought the brothers into the house of Joseph and received them hospitably. When the Vizier (Joseph) appeared, they gave him gifts from their father. Joseph saw and inquired of Benjamin, and was overcome by emotion but did not show it. He withdrew to his chambers and wept. When he regained control of himself, he returned and ordered a meal to be served. The Egyptians would not dine with Hebrews at the same table, as doing so was considered loathsome, thus the sons of Israel were served at a separate table (Genesis 43:16–44:34).

That night, Joseph ordered his steward to load the brothers' donkeys with food and all their money. The money they had brought was double what they had offered on the first trip. Deceptively, Joseph also ordered the steward to put his silver cup in Benjamin's sack. The following morning the brothers began their journey back to Canaan. Joseph ordered the steward to go after the brothers and to question them about the "missing" silver cup. When the steward caught up with the brothers, he seized them and searched their sacks. The steward found the cup in Benjamin's sack - just as he had planted it the night before. This caused a stir amongst the brothers. However, they agreed to be escorted back to Egypt. When the Vizier (Joseph) confronted them about the silver cup, he demanded that the one who possessed the cup in his bag become his slave. In response, Judah pleaded with the Vizier that Benjamin be allowed to return to his father, and that he himself be kept in Benjamin's place as a slave (Genesis 44).

Family reunited

[edit]

Judah appealed to the Vizier begging that Benjamin be released and that he be enslaved in his stead, because of the silver cup found in Benjamin's sack. The Vizier broke down into tears. He could not control himself any longer and so he sent the Egyptian men out of the house. Then he revealed to the Hebrews that he was in fact their brother, Joseph. He wept so loudly that even the Egyptian household heard it outside. The brothers were frozen and could not utter a word. He brought them closer and relayed to them the events that had happened and told them not to fear, that what they had meant for evil, God had meant for good. Then he commanded them to go and bring their father and his entire household into Egypt to live in the province of Goshen, because there were five more years of famine left. So Joseph supplied them Egyptian transport wagons, new garments, silver money, and twenty additional donkeys carrying provisions for the journey. (Genesis 45:1–28)

Thus, Jacob (also known as Israel) and his entire house of seventy[21] gathered up with all their livestock and began their journey to Egypt. As they approached Egyptian territory, Judah went ahead to ask Joseph where the caravan should unload. They were directed into the province of Goshen and Joseph readied his chariot to meet his father there.[i] It had been over twenty years since Joseph had last seen his father. When they met, they embraced each other and wept together for quite a while. His father then remarked, "Now let me die, since I have seen your face, because you are still alive." (Genesis 46:1–34)

Afterward, Joseph's family personally met the Pharaoh of Egypt. The Pharaoh honoured their stay and even proposed that if there were any qualified men in their house, then they may elect a chief herdsman to oversee Egyptian livestock. Because the Pharaoh had such a high regard for Joseph, practically making him his equal,[22] it had been an honour to meet his father. Thus, Israel was able to bless the Pharaoh (Genesis 47:1–47:12).[23] The family was then settled in Goshen.

Father's blessing and passing

[edit]

The house of Israel acquired many possessions and multiplied exceedingly during the course of seventeen years, even through the worst of the seven-year famine. At this time, Joseph's father was 147 years old and bedridden. He had fallen ill and lost most of his vision. Joseph was called into his father's house and Israel pleaded with his son that he not be buried in Egypt. Rather, he requested to be carried to the land of Canaan to be buried with his forefathers. Joseph was sworn to do as his father asked of him. (Genesis 47:27–31)

Later, Joseph came to visit his father having with him his two sons, Ephraim and Manasseh. Israel declared that they would be heirs to the inheritance of the house of Israel, as if they were his own children, just as Reuben and Simeon were. Then Israel laid his left hand on the eldest Mannasseh's head and his right hand on the youngest Ephraim's head and blessed Joseph. However, Joseph was displeased that his father's right hand was not on the head of his firstborn, so he switched his father's hands. But Israel refused saying, "but truly his younger brother shall be greater than he," a declaration he made just as Israel himself was to his firstborn brother Esau. To Joseph, he gave a portion more of Canaanite property than he had to his other sons; land that he fought for against the Amorites. (Genesis 48:1–22)

Then Israel called all of his sons in and prophesied their blessings or curses to all twelve of them in order of their ages. To Joseph he declared:

Joseph is a fruitful bough, even a fruitful bough by a well; whose branches run over the wall. The archers have sorely grieved him, and shot at him, and hated him: But his bow abode in strength, and the arms of his hands were made strong by the hands of the Mighty God of Jacob (From thence is the Shepherd, the Stone of Israel), Even by the God of your father who shall help thee; and by the Almighty who shall bless thee With blessings of heaven above, Blessings of the deep that lieth under, Blessings of the breasts and of the womb. The blessings of thy father have prevailed above the blessings of my progenitors unto the utmost bound of the everlasting hills. They shall be on the head of Joseph, And on the crown of the head of him that was separate from his brethren.

After relaying his prophecies, Israel died. The family, including the Egyptians, mourned him seventy days. Joseph had his father embalmed, a process that took forty days. Then he prepared a great ceremonial journey to Canaan leading the servants of the Pharaoh, and the elders of the houses Israel and Egypt beyond the Jordan River. They stopped at Atad where they observed seven days of mourning. Here, their lamentation was so great that it caught the attention of surrounding Canaanites who remarked "This is a deep mourning of the Egyptians." So they named this spot Abel Mizraim. Then Joseph buried Israel in the cave of Machpelah, the property of Abraham when he bought it from the Hittites. (Genesis 49:33–50:14)

After their father died, the brothers of Joseph feared retribution for being responsible for Joseph's deliverance into Egypt as a slave. Joseph wept as they spoke and told them that what had happened was God's purpose to save lives and the lives of his family. He comforted them and their ties were reconciled. (Genesis 50:15–21)

Joseph's burial

[edit]

Joseph lived to the age of 110, living to see his great-grandchildren. Before he died, he made the children of Israel swear that when they left the land of Egypt they would take his bones with them, and on his death his body was embalmed and placed in a coffin in Egypt. (Genesis 50:22–26)

The children of Israel remembered their oath, and when they left Egypt during the Exodus, Moses took Joseph's bones with him. (Exodus 13:19) The bones were buried at Shechem, in the parcel of ground which Jacob bought from the sons of Hamor (Joshua 24:32), which has traditionally been identified with site of Joseph's Tomb, before Jacob and all his family moved to Egypt. Shechem was in the land which was allocated by Joshua to the Tribe of Ephraim, one of the tribes of the House of Joseph, after the conquest of Canaan.

Composition and literary motifs

[edit]

In 1970, Donald B. Redford argued that the composition of the story could be dated to the period between the 7th century BCE and the third quarter of the 5th century BCE.[24] By the early 1990s, a majority of modern scholars agreed that the Joseph story was a Wisdom novella constructed by a single author and that it reached its current form in the 5th century BCE at the earliest—with Soggin suggesting the possibility of a first or early second century BCE date.[25] Some scholars argue that the core of the story could be traced back to a 2nd millennium BCE context.[26][27] Thomas Römer argues that “The date of the original narrative can be the late Persian period, and while there are several passages that fit better into a Greek, Ptolemaic context, most of these passages belong to later revisions.”[28]

The motif of dreams/dream-interpretation contributes to a strong story-like narrative.[29][30] The plot begins by showing Joseph as a dreamer; this leads him into trouble as, out of envy, his brothers sell him into slavery. The next two instances of dream interpretation establish his reputation as a great interpreter of dreams; first, he begins in a low place, interpreting the dreams of prisoners. Then Joseph is summoned to interpret the dreams of Pharaoh himself.[31] Impressed with Joseph's interpretations, Pharaoh appoints him as second-in-command (Gen 41:41). This sets up the climax of the story, which many regard to be the moment Joseph reveals his identity to his brothers (Gen 45:3).

Jewish tradition

[edit]Selling Joseph

[edit]

In the midrash, the selling of Joseph was part of God's divine plan for him to save his tribes. The favoritism Israel showed Joseph and the plot against him by his brothers were divine means of getting him into Egypt.[32] Maimonides comments that even the villager in Shechem, about whom Joseph inquired his brother's whereabouts, was a "divine messenger" working behind the scene.[33]

A midrash asked, How many times was Joseph sold? In analyzing Genesis Chapter 37, there are five different Hebrew names used to describe five different groups of people involved in the transaction of selling Joseph, according to Rabbi Judah and Rav Huna. The first group identified, are Joseph's brothers when Judah brings up the idea of selling Joseph in verses 26 and 27. The first mention of Ishmaelites (Yishma'elîm) is in verse 25. Then the Hebrew phrase ʼnāshîm midyanîm sōĥrîm in verse 28 describes Midianite traders. A fourth group in verse 36 is named in Hebrew as m‘danîm that is properly identified as Medanites. The final group, where a transaction is made, is among the Egyptians in the same verse.

After identifying the Hebrew names, Rabbi Judah claims that Joseph was sold four times: First his brothers sold Joseph to the Ishmaelites (Yishma'elîm), then the Ishmaelites sold him to the Midianite traders (ʼnāshîm midyanîm sōĥrîm), the Midianite traders to the Medanites (m‘danîm), and the Medanites into Egypt. Rav Huna adds one more sale by concluding that after the Medanites sold him to the Egyptians, a fifth sale occurred when the Egyptians sold him to Potiphar. (Genesis Rabbah 84:22)

Potiphar's wife

[edit]Joseph had good reasons not to have an affair with Potiphar's wife: he did not want to abuse his master's trust; he believed in the sanctity of marriage; and it went against his ethical, moral and religious principles taught to him by his father Jacob. According to the Midrash, Joseph would have been immediately executed by the sexual assault charge against him by Potiphar's wife. Abravanel explains that she had accused other servants of the same crime in the past. Potiphar believed that Joseph was incapable of such an act and petitioned Pharaoh to spare his life.[34] However, punishment could not have been avoided because of her class status and limited public knowledge of her scheme.

According to Legends of the Jews, the name of Potiphar's wife is Zuleikha and when she was enticing Joseph to give up to her sinful passion, God appeared unto him, holding the foundation of earth (Eben Shetiyah), that He would destroy the world if Joseph touched her.[35]

Silver cup for divination

[edit]Jewish tradition holds that Joseph had his steward plant his personal silver cup in Benjamin's sack to test his brothers. He wanted to know if they would be willing to risk danger in order to save their half brother Benjamin. Since Joseph and Benjamin were born from Rachel, this test was necessary to reveal if they would betray Benjamin as they did with Joseph when he was seventeen. Because Joseph the Dreamer predicts the future by analyzing dreams, alternative Jewish tradition claims that he practiced divination using this silver cup as the steward charged[36] and as Joseph himself claimed in Genesis 44:15.[37]

Raising Joseph

[edit]In one Talmudic story, Joseph was buried in the Nile river, as there was some dispute as to which province should be honoured by having his tomb within its boundaries. Moses, led there by an ancient holy woman named Serach, was able by a miracle to raise the sarcophagus and to take it with him at the time of the Exodus.

Christian tradition

[edit]

Joseph is mentioned in the New Testament as an example of faith (Hebrews 11:22). Joseph is commemorated as one of the Holy Forefathers in the Calendar of Saints of the Armenian Apostolic Church on 26 July. In the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite, he is known as "Joseph the all-comely", a reference not only to his physical appearance, but more importantly to the beauty of his spiritual life. They commemorate him on the Sunday of the Holy Forefathers (two Sundays before Christmas) and on Holy and Great Monday (Monday of Holy Week). In icons, he is sometimes depicted wearing the nemes headdress of an Egyptian vizier. The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod commemorates him as a patriarch on 31 March.

In addition to honouring him, there was a strong tendency in the patristic period to view his life as a typological precursor to Christ.[38] This tendency is represented in John Chrysostom who said that Joseph's suffering was "a type of things to come",[39] Caesarius of Arles who interpreted Joseph's famous coat as representative of the diverse nations who would follow Christ,[40] Ambrose of Milan who interpreted the standing sheaf as prefiguring the resurrection of Christ,[41] and others.

This tendency, although greatly diminished, was followed throughout late antiquity, the Medieval Era, and into the Reformation. Even John Calvin, sometimes hailed as the father of modern grammatico-historical exegesis,[42] writes "in the person of Joseph, a lively image of Christ is presented."[43]

In addition, some Christian authors have argued that this typological interpretation finds its origin in the speech of Stephen in Acts 7:9–15, as well as the Gospel of Luke and the parables of Jesus, noting strong verbal and conceptual collocation between the Greek translation of the portion of Genesis concerning Joseph and the Parable of the Wicked Tenants and the Parable of the Prodigal Son.[44]

Gregory of Tours claimed that Joseph built the pyramids and they were used as granaries.[45]

Islamic tradition

[edit]

Joseph (Arabic: يوسُف, Yūsuf) is regarded by the Quran as a prophet (Quran 6:84), and a whole chapter Surah Yusuf 12 is devoted to him, the only instance in the Quran in which an entire chapter is devoted to a complete story of a person. It is described in the Quran as the 'best of stories'.[46] Joseph is said to have been extremely handsome, which attracted his Egyptian master's wife to attempt to seduce him. Muhammad is believed to have once said, "One half of all the beauty God apportioned for mankind went to Joseph and his mother; the other one half went to the rest of mankind."[47] The story has a lot in common with the biblical narrative, but with certain differences.[48] In the Quran the brothers ask Jacob ("Yaqub") to let Joseph go with them.[49] Joseph is thrown into a well, and was taken as a slave by a passing caravan. When the brothers claimed to the father that a wolf had eaten Joseph, he observed patience.[50]

In the Bible, Joseph discloses himself to his brethren before they return to their father the second time after buying grain.[51] But in Islam they returned leaving behind Benjamin because the King’s measuring cup was found in his bag.[52] Similarly, the eldest son of Jacob had decided not to leave the land because of the oath taken to protect Benjamin beforehand.[53] When Jacob learned their story after their return, he cried in grief for so long that he lost his eyesight because of sorrow.[54] He thus charged his sons to go and inquire about Joseph and his brother and despair not of God's mercy. It was during this return to Egypt that Joseph disclosed his real identity to his brothers. He admonished and forgave them, he sent also his garment which healed the patriarch's eyes as soon as it was cast unto his face.[55] The remaining verses describe the migration of Jacob's family to Egypt and the emotional meeting of Jacob and his long lost son, Joseph. The family prostrated before him hence the fulfilment of his dream aforetime.[56]

The story concludes by Joseph praying,

“My Lord! You have surely granted me authority and taught me the interpretation of dreams. ˹O˺ Originator of the heavens and the earth! You are my Guardian in this world and the Hereafter. Allow me to die as one who submits and join me with the righteous.”

Baha'i tradition

[edit]There are numerous mentions of Joseph in Bahá'í writings.[57] These come in the forms of allusions written by the Báb and Bahá'u'lláh. In the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, Bahá'u'lláh states that "from my laws, the sweet-smelling savour of my garment can be smelled" and, in the Four Valleys, states that "the fragrance of his garment blowing from the Egypt of Baha," referring to Joseph.

Bahá'í commentaries have described these as metaphors with the garment implying the recognition of a manifestation of God. In the Qayyumu'l-Asma', the Báb refers to Bahá'u'lláh as the true Joseph and makes an analogous prophecy regarding Bahá'u'lláh suffering at the hands of his brother, Mírzá Yahyá.[58]

Literature and culture

[edit]- Somnium morale Pharaonis (13th century), by Cistercian monk Jean de Limoges, is a collection of fictional letters exchanged between the Pharaoh, Joseph, and other characters of the narrative regarding the interpretation of the Pharaoh's dream.

- Joseph and his Brethren, 1743, an oratorio by George Frideric Handel.

- Josephslegende (The Legend of Joseph) is a 1914 work by Richard Strauss for the Ballets Russes.

- Joseph and His Brothers (1933–1943), a four-novel omnibus by Thomas Mann, retells the Genesis stories surrounding Joseph, identifying Joseph with the figure of Osarseph known from Josephus, and the pharaoh with Akhenaten.

- In the 1961 Yugoslavian/Italian film, The Story of Joseph and His Brethren (Giuseppe Venduto dai Fratelli) Joseph is played by Geoffrey Horne.

- In the 1974 film, The Story of Jacob and Joseph he is portrayed by Tony Lo Bianco.

- The 1979, New Media Bible Genesis Project (TV)-cap. Joseph And His Brothers[59]

- The long-running musical Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice is based on the biblical story of Joseph, up through Genesis chapter 46. It was adapted into the 1999 film of the same name.

- In 1995, Turner Network Television released the made-for-television film Joseph starring Ben Kingsley as Potiphar, Lesley Ann Warren as Potiphar's wife, Paul Mercurio as Joseph and Martin Landau as Jacob.

- In 2000, DreamWorks Animation released a direct-to-video animated musical film based on the life of Joseph, titled Joseph: King of Dreams. American actor Ben Affleck provided the speaking voice of Joseph, and the Australian singer David Campbell doubled as singing voice of Joseph and the singing narrator of the film

- The 2003 VeggieTales children's video The Ballad of Little Joe retells Joseph's Genesis stories in the style and setting of an American Western film.

- Prophet Joseph (2008–2009) is an Iranian television series, directed by Farajollah Salahshoor, which tells the story of Prophet Joseph from the Quran and Islamic traditions. Joseph is played by Mostafa Zamani as an adult and by Hossein Jafarias when younger.

- The cultural impact of the Joseph story in early-modern times is discussed in Lang 2009.

- Rappresentatione di Giuseppe e i suoi Fratelli/Joseph and his Brethren - a musical drama in three acts composed by Elam Rotem for ensemble Profeti della Quinta (2013, Pan Classics).

- The Red Tent is a 1997 novel by Anita Diamant focused on Joseph's half-sister Dinah. It was addapted for television as a two-part miniseries of the same name in 2014. Joseph himself appears as a secondary character in both the book and its addaptation and is portrayed in the series by Will Tudor.

- The 2015 animated film Joseph: Beloved Son, Rejected Slave, Exalted Ruler is based on the life of Joseph. American voice actor Mike McFarland provides the speaking voice of Joseph.

- José do Egito (English: Joseph of Egypt) is a Brazilian miniseries produced and broadcast by RecordTV. It premiered on January 30, 2013, and ended on October 9, 2013. It is based on the biblical account of the book of Genesis that deals with the patriarch Joseph, son of Jacob. Joseph is played by Ângelo Paes Leme as an adult and by Ricky Tavares in his younger years.

- The 2019 novel Joseph and the Way of Forgiveness by Stephen Mitchell retells the story of Joseph in the form of a midrash with emphasis on the thoughts and beliefs of a flawed Joseph.

- Gênesis (English: Genesis) is a Brazilian telenovela produced and broadcast by RecordTV. Divided into seven phases or parts, the series tells the story of the entire biblical book of Genesis, focusing specifically on Joseph in the last one, subtitled José do Egito (English: Joseph of Egypt). Joseph is played by Juliano Laham as an adult and by João Guilherme Chaseliov as a child.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Standard: Yōsef, Tiberian: Yōsēp̄; alternatively: יְהוֹסֵף,[3][4] lit. 'Yahweh shall add'; Standard: Yəhōsef, Tiberian: Yŏhōsēp̄;[5] Arabic: يوسف, romanized: Yūsuf; Ancient Greek: Ἰωσήφ, romanized: Iōsēph

- ^ Another possible translation is "coat with long sleeves" (Jastrow 1903)

- ^ According to Josephus, Reuben tied a cord around Joseph and let him down gently into the pit. Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 2.3.2., Perseus Project AJ2.3.2, .

- ^ The Septuagint sets his price at twenty pieces of gold; the Testament of Gad thirty of gold; the Hebrew and Samaritan twenty of silver; the Vulgar Latin thirty of silver; Josephus at twenty pounds

- ^ Josephus claims that Potiphar fell for his wife's crocodile tears although he did not believe Joseph capable of the crime.Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 2.4.1., Perseus Project AJ2.4.1, .

- ^ Josephus refers to the name Zaphnath-Paaneah as Psothom Phanech meaning "the revealer of secrets" Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 2.6.1., Perseus Project AJ2.6.1, .

- ^ Josephus refers to Potipherah (or Petephres) as the priest of Heliopolis. Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 2.6.1., Perseus Project AJ2.6.1, .

- ^ William Whiston comments that Simeon was chosen as a pledge for the sons of Israel's return to Egypt because of all the brothers who hated Joseph the most, was Simeon, according to the Testament of Simeon and the Testament of Zebulun. Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 2.6.4., Perseus Project AJ2.6.4, . Note 1.

- ^ Josephus has Joseph meeting his father Jacob in Heliopolis, a store-city with Pithom and Raamses, all located in the Egyptian country of Goshen. Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 2.7.5., Perseus Project AJ2.7.5, .

Citations

[edit]- ^ Genesis 46:20

- ^ Gesenius & Robinson 1882, p. 391.

- ^ "Psalms 81:6". Sefaria.

- ^ "Strong's Hebrew Concordance - 3084". Bible Hub.

- ^ Khan, Geoffrey (2020). The Tiberian Pronunciation Tradition of Biblical Hebrew, Volume 1. Open Book Publishers. ISBN 978-1783746767.

- ^ Binder, Susanne (2011). "Joseph's Rewarding and Investiture (Genesis 41:41-43) and The Gold Of Honour In New Kingdom Egypt". In Bar, S.; Kahn, D.; Shirley, J. J. (eds.). Egypt, Canaan and Israel: History, Imperialism, Ideology and Literature: Proceedings of a Conference at the University of Haifa, 3-7 May 2009. BRILL. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-90-04-19493-9.

- ^ Rezetko 2022, p. 31.

- ^ Schipper, Bernd. “The Egyptian Background of the Joseph Story.” Hebrew Bible and Ancient Israel 8/1 (2019): 6–23. “The Joseph story is best described as a diaspora-novella that expresses a concept of identity which reflects Judeans/Israelites living in Persian period Egypt.”

- ^ Römer, Thomas. “The Joseph Story in the Book of Genesis: Pre-P or Post-P?” In The Post-Priestly Pentateuch: New Perspectives on its Redactional Development and Theological Profiles, edited by Federico Giuntoli and Konrad Schmid, 185-201. FAT 101. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2015. “The Joseph narrative, now integrated into Gen 37-50, was originally an independent Diaspora novella composed during the Persian period, probably by a member of the Hebrews living in Egypt in order to legitimate a life outside the land.”

- ^ Blidstein, Gerald J. (2007). Skolnik, Fred; Berenbaum, Michael; Thomson Gale (Firm) (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 14. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4. OCLC 123527471. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ "Strong's Hebrew Concordance - 622. asaph". Bible Hub.

- ^ "Genesis 30:23". Bible Hub.

- ^ "Strong's Hebrew Concordance - 3254. yasaph". Bible Hub.

- ^ "Genesis 30:24". Bible Hub.

- ^ Friedman, R.E., The Bible With Sources Revealed, (2003), p. 80

- ^ Genesis 37:21–22

- ^ Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 2.3.1., Perseus Project AJ2.3.1, .

- ^ "Strong's Hebrew: 6847. צָפְנַת (Tsaphenath Paneach) -- "the god speaks and he lives," Joseph's Eg. name". biblehub.com.

- ^ Genesis 45:11

- ^ Genesis 42:23

- ^ Genesis 46:27

- ^ Genesis 44:18

- ^ See Guy Darshan, “The Priestly Account of the End of Jacob’s Life: The Significance of Text-Critical Evidence,” in: B. Hensel (ed.), The History of the Jacob Cycle (Genesis 25-35), Tübingen 2021, 183–199.

- ^ Redford 1970, p. 242: "several episodes in the narrative, and the plot motifs themselves, find some parallel in Saite, Persian, or Ptolemaic Egypt. It is the sheer weight of evidence, and not the argument from silence, that leads to the conclusion that the seventh century B.C. is the terminus a quo for the Egyptian background to the Joseph Story. If we assign the third quarter of the fifth century B.C.E. as the terminus ante quem, we are left with a span of two and one half centuries, comprising in terms of Egyptian history the Saite and early Persian periods."

- ^ Soggin 1993, pp. 102–103, 336, 343–344.

- ^ Binder 2011, p. 60.

- ^ Shupak 2020, p. 352.

- ^ T. Römer, “How “Persian” or “Hellenistic” is the Joseph Narrative?”, in T. Römer, K. Schmid et A. Bühler (ed.), The Joseph Story Between Egypt and Israel (Archaeology and Bible 5), Tübinngen: Mohr Siebeck, 2021, pp. 35-53

- ^ Kugel 1990, p. 13.

- ^ Redford 1970, p. 69.

- ^ Lang 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Scharfstein 2008, p. 124.

- ^ Scharfstein 2008, p. 120.

- ^ Scharfstein 2008, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Ginzberg, Louis (1909). The Legends of the Jews. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society. pp. 44–52.

Then the Lord appeared unto him, holding the Eben Shetiyah in His hand, and said to him: "If thou touchest her, I will cast away this stone upon which the earth is founded, and the world will fall to ruin.".

- ^ Genesis 44:15

- ^ Scharfstein 2008, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Smith, Kathryn (1993), "History, Typology and Homily: The Joseph Cycle in the Queen Mary Psalter", Gesta, 32 (2): 147–59, doi:10.2307/767172, ISSN 0016-920X, JSTOR 767172, S2CID 155781985

- ^ Chrysostom, John (1992), Homilies on Genesis, 46-47, trans. Robert C. Hill, Washington DC: Catholic University of America Press, p. 191

- ^ Sheridan, Mark (2002), Genesis 11-50, Downers Grove: InterVarsity, p. 231

- ^ Sheridan, Mark (2002), Genesis 11-50, Downers Grove: InterVarsity, p. 233

- ^ Blacketer, Raymond (2006), "The School of God: Pedagogy and Rhetoric in Calvin's Interpretation of Deuteronomy", Studies in Early Modern Religious Reforms, vol. 3, pp. 3–4

- ^ Calvin, John (1998), Commentaries on the First Book of Moses Called Genesis, vol. 2, Grand Rapids: Baker, p. 261

- ^ Lunn, Nicholas (March 2012), "Allusions to the Joseph Narrative in the Synoptic Gospels and Acts: Foundations of a Biblical Type" (PDF), Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society: 27–41, ISSN 0360-8808

- ^ A history of the Franks, Gregory of Tours, Pantianos Classics, 1916

- ^ Quran 12:3

- ^ Tottoli 2002, p. 120.

- ^ Quran 12:1

- ^ Quran 12:12

- ^ Quran 12:15-18

- ^ "JOSEPH - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com.

- ^ Quran 12:72-76

- ^ Quran 12:80

- ^ Quran 12:84

- ^ Quran 12:87-96

- ^ Quran 12:100

- ^ Stokes, Jim. The Story of Joseph in the Babi and Baha'i Faiths in World Order, 29:2, pp. 25-42, 1997-98 Winter.

- ^ Naghdy 2012, p. 563.

- ^ "The New Media Bible: Book of Genesis (Video 1979)". IMDb.

Sources

[edit]- Gesenius, Wilhelm; Robinson, Edward (1882). A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament. Houghton Mifflin and Company.

- Jastrow, Marcus (1903). A dictionary of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi, and the Midrashic literature. Vol. 1. London: Luzac & Co.

- Kugel, James L. (1990). In Potiphar's House: The Interpretive Life of Biblical Texts. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 978-0-06-064907-4.

- Lang, Bernhard (2009). Joseph in Egypt: A Cultural Icon from Grotius to Goethe. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15156-5.

- Naghdy, Fazel (2012). A Tutorial on the Kitab-i-iqan: A Journey Through the Book of Certitude. Fazel Naghdy. ISBN 978-1-4663-1100-8.

- Redford, Donald B. (1970). A study of the biblical story of Joseph: (Genesis 37–50). Leiden: Brill.

- Redford, Donald B. (1993) [1992]. Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00086-2.

- Rezetko, Robert (2022). "A Coat of Many Colors and a Range of Many Dates: The Origins of the Story of Joseph in Genesis 37–50". In Van Hecke, Pierre; Van Loon, Hanneke (eds.). Where Is the Way to the Dwelling of Light?: Studies in Genesis, Job and Linguistics in Honor of Ellen van Wolde. BRILL. pp. 3–39. ISBN 978-90-04-53629-6.

- Scharfstein, Sol (2008). Torah and Commentary: The Five Books of Moses : Translation, Rabbinic and Contemporary Commentary. KTAV. ISBN 978-1-60280-020-5.

- Shupak, Nili (2020). "The Egyptian Background of the Joseph Story: Selected Issues Revisited". In Averbeck, Richard E.; Younger (Jr.), K. Lawson (eds.). "An Excellent Fortress for His Armies, a Refuge for the People": Egyptological, Archaeological, and Biblical Studies in Honor of James K. Hoffmeier. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-1-57506-994-4.

- Soggin, J. A. (1993). "Notes on the Joseph Story". In A. Graeme Auld (ed.). Understanding Poets and Prophets: Essays in Honour of George Wishart Anderson. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9781850754275.

- Tottoli, Roberto (2002). Biblical Prophets in the Qur'ān and Muslim Literature. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1394-3.

Further reading

[edit]- de Hoop, Raymond (1999). Genesis 49 in its literary and historical context. Oudtestamentische studiën, Oudtestamentisch Werkgezelschap in Nederland. Vol. 39. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-10913-1.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2001). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-2338-6. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- Genung, Matthew C. (2017). The Composition of Genesis 37: Incoherence and Meaning in the Exposition of the Joseph Story. Forschungen zum Alten Testament 2. Reihe. 95. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-155150-5.

- Goldman, Shalom (1995). The wiles of women/the wiles of men: Joseph and Potiphar's wife in ancient Near Eastern, Jewish, and Islamic folklore. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2683-8.

- Louden, Bruce (2011). "The Odyssey and the myth of Joseph; Autolykos and Jacob". Homer's Odyssey and the Near East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–104. ISBN 978-0-521-76820-7.

- Moore, Megan Bishop; Kelle, Brad E (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-6260-0.

- Rivka, Ulmer (2009). Egyptian cultural icons in Midrash. Studia Judaica. Vol. 52. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-022392-7. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- Schenke, Hans-Martin (1968). "Jacobsbrunnen-Josephsgrab-Sychar. Topographische Untersuchungen und Erwägungen in der Perspektive von Joh. 4,5.6". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 84 (2): 159–84. JSTOR 27930842.

- Sills, Deborah (1997). "Strange Bedfellows: Politics and Narrative in Philo". In Breslauer, S. Daniel (ed.). The seductiveness of Jewish myth: challenge or response?. SUNY series in Judaica. SUNY. pp. 171–90. ISBN 978-0-7914-3602-8. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

- Sperling, S. David (2003). The Original Torah: The Political Intent of the Bible's Writers. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9833-1.

- Völter, Daniel (1909). Aegypten und die Bibel: die Urgeschichte Israels im Licht der aegyptischen Mythologie (4th ed.). Leiden: E.J. Brill. Retrieved 8 September 2011.

External links

[edit] Media related to Joseph (son of Jacob) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Joseph (son of Jacob) at Wikimedia Commons- BBC - Joseph

Joseph (Genesis)

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Background

Name and Linguistic Origins

The Hebrew name of Joseph, rendered as Yosef (יוֹסֵף), derives from the Semitic root y-s-p, specifically the hiphil jussive form of the verb yāsap (יסף), meaning "to add" or "to increase."[14] This etymology is explicitly linked in the biblical text to Rachel's declaration upon his birth in Genesis 30:24, where she states, "May the Lord add (yōsēp) to me another son," expressing hope for further progeny amid her initial barrenness.[14] The name thus embodies a prayer for divine augmentation of the family line. A secondary etiology for Yosef appears in the preceding verse (Genesis 30:23), where Rachel associates it with the root ʾ-s-p (אסף), meaning "to take away" or "to gather," as she rejoices that God "has taken away (ʾāsap)" her reproach of childlessness.[15] This wordplay highlights dual connotations of removal of shame and addition of blessing, a common feature in biblical naming practices that reinforces thematic depth.[15] In the narrative, Joseph receives an Egyptian name, Zaphenath-paneah (צָפְנַת פַּעְנֵחַ), bestowed by Pharaoh upon his elevation to power (Genesis 41:45). Scholarly analysis suggests this is a transcription of an Egyptian phrase or title, possibly ḏd-pꜣ-nṯr-iw.f ꜥnḫ, meaning "this one whom the god has said will live" or a variant indicating divine favor and vitality.[16] Some proposals connect it to administrative or prophetic roles, such as "revealer of hidden things," aligning with Joseph's interpretive abilities, though the precise rendering remains debated due to phonetic adaptations from Egyptian to Hebrew.[17] While Yosef itself lacks direct Egyptian etymological ties and remains a standard Yahwistic Hebrew name, the dual naming underscores cultural assimilation in the Egyptian context.[18] Variants of the root y-s-p appear in other ancient Near Eastern texts, reflecting broader Semitic linguistic patterns; for instance, cognates exist in Arabic (yasafa, "to add") and potentially in Akkadian forms related to accumulation, though no exact personal name parallels to Yosef are attested in Ugaritic or Akkadian corpora.[19] In Ugaritic, similar verbal roots denote increase or repetition, supporting the name's integration within Northwest Semitic naming conventions.[20] Symbolically, Yosef's meaning of "increase" resonates throughout the Genesis narrative, foreshadowing Joseph's role in preserving and multiplying his family's lineage during famine through strategic provision in Egypt.[14] This theme culminates in Jacob's blessing (Genesis 49:22), portraying Joseph as a "fruitful bough" whose branches extend, emblematic of divine abundance and the expansion of Israel's seed.[14]Familial and Historical Context

Joseph was the eleventh son of Jacob, who was later renamed Israel, and the first of two sons born to Jacob's favored wife, Rachel; his younger brother Benjamin completed the pair born to her. As detailed in the Book of Genesis, Jacob's family formed the nucleus of the Israelite tribes, with Joseph's siblings representing the foundational lineages that would evolve into the Twelve Tribes of Israel. This genealogy underscores the patriarchal structure of the Hebrew people, where descent through male lines established tribal identities central to ancient Israelite society. The full roster of Jacob's sons, as enumerated in Genesis, is as follows, grouped by their mothers to highlight the complex familial dynamics involving Jacob's wives and concubines:| Mother | Sons (Birth Order) |

|---|---|

| Leah | Reuben, Simeon, Levi, Judah, Issachar, Zebulun |

| Bilhah (Rachel's maid) | Dan, Naphtali |

| Zilpah (Leah's maid) | Gad, Asher |

| Rachel | Joseph, Benjamin |

.jpg/250px-Joseph_Overseer_of_the_Pharaohs_Granaries_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)