Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Vayeira

View on WikipediaThis article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (February 2025) |

Vayeira, Vayera, or Va-yera (וַיֵּרָא—Hebrew for "and He appeared," the first word in the parashah) is the fourth weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading. It constitutes Genesis 18:1–22:24. The parashah tells the stories of Abraham's three visitors, Abraham's bargaining with God over Sodom and Gomorrah, Lot's two visitors, Lot's bargaining with the Sodomites, Lot's flight, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, how Lot's daughters became pregnant by their father, how Abraham once again passed off his wife Sarah as his sister, the birth of Isaac, the expulsion of Hagar, disputes over wells, and the binding of Isaac (הָעֲקֵידָה, the Akedah).

The parashah has the most words (but not the most letters or verses) of any of the weekly Torah portions in the Book of Genesis, and its word-count is second only to Parashat Naso in the entire Torah. It is made up of 7,862 Hebrew letters, 2,085 Hebrew words, 147 verses, and 252 lines in a Torah Scroll (Sefer Torah). (In the Book of Genesis, Parashat Miketz has the most letters, and Parashiyot Noach and Vayishlach have the most verses.)[1]

Jews read it on the fourth Sabbath after Simchat Torah, in October or November.[2] Jews also read parts of the parashah as Torah readings for Rosh Hashanah. Genesis 21 is the Torah reading for the first day of Rosh Hashanah, and Genesis 22 is the Torah reading for the second day of Rosh Hashanah. In Reform Judaism, Genesis 22 is the Torah reading for the one day of Rosh Hashanah.

Readings

[edit]In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings (עליות, aliyot). In the Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashat Vayeira has four "open portion" (פתוחה, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter פ (peh)). Parashat Vayeira has two further subdivisions, called "closed portion" (סתומה, setumah) divisions (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter ס (samekh)) within the first open portion. The first open portion, petuchah) spans the first five readings. The second open portion coincides with the sixth reading. The third open portion covers the binding of Isaac, which is most of the seventh reading, excluding only the concluding maftir (מפטיר) reading. And the fourth open portion coincides with the concluding maftir reading. Closed portion divisions further divide the long fourth reading.[3]

First reading – Genesis 18:1–14

[edit]In the first reading, as Abraham was sitting in the entrance of his tent by the terebinths of Mamre in the heat of the day, he looked up and saw God in the form of three men. He ran, bowed to the ground, and welcomed them.[4] Abraham offered to wash their feet and fetch them a morsel of bread, and they assented.[5] Abraham rushed to Sarah's tent to order cakes made from choice flour, ran to select a choice calf for a servant-boy to prepare, set curds and milk and the calf before them, and waited on them under the tree as they ate.[6] (In Genesis 18:9, there are dots above the letters א, ל, and ו in "They said to him.") One of the visitors told Abraham that he would return the next year, and Sarah would have a son, but Sarah laughed to herself at the prospect, with Abraham so old.[7] God then asked Abraham why Sarah had laughed at bearing a child at her age, noting that nothing was too wondrous for God.[8] The first reading ends here.[9]

Second reading – Genesis 18:15–33

[edit]In the second reading, frightened, Sarah denied laughing, but God insisted that she had.[10] The men set out toward Sodom, and Abraham walked with them to see them off.[11] God considered whether to confide in Abraham what God was about to do, since God had singled out Abraham to become a great nation and instruct his posterity to keep God's way by doing what was just and right.[12] God told Abraham that the outrage and sin of Sodom and Gomorrah was so great that God was going to see whether they had acted according to the outcry that had reached God.[13] The men went on to Sodom, while Abraham remained standing before God.[14] Abraham pressed God whether God would sweep away the innocent along with the guilty, asking successively if there were 50, or 45, or 40, or 30, or 20, or 10 innocent people in Sodom, would God not spare the city for the sake of the innocent ones, and each time God agreed to do so.[15] When God had finished speaking to Abraham, God departed, and Abraham returned to his place.[16] The second reading ends here with the end of chapter 18.[17]

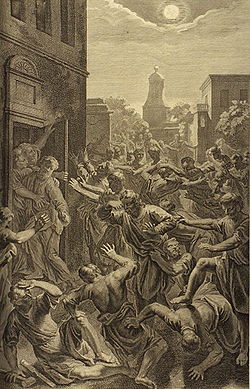

Third reading – Genesis 19:1–20

[edit]In the third reading, as Lot was sitting at the gate of Sodom in the evening, the two angels arrived, and Lot greeted them and bowed low to the ground.[18] Lot invited the angels to spend the night at his house and bathe their feet, but they said that they would spend the night in the square.[19] Lot urged them strongly, so they went to his house, and he prepared a feast for them and baked unleavened bread, and they ate.[20] Before they had retired for the night, all the men of Sodom gathered about the house shouting to Lot to bring his visitors out so that they might be intimate with them.[21] Lot went outside the entrance, shutting the door behind him, and begged the men of Sodom not commit such a wrong.[22] Lot offered the men his two virgin daughters, if they would not do anything to his guests, but they disparaged Lot as one who had come as an alien and now sought to rule them, and they pressed threateningly against him.[23] But the visitors stretched out their hands and pulled Lot back into the house and shut the door and struck the people with blindness so that they were unable to find the door.[24] The visitors directed Lot to bring what family he had out of the city, for they were about to destroy the place, because the outcry against its inhabitants had become so great.[25] So Lot told his sons-in-law that they needed to get out of the place because God was about to destroy it, but Lot's sons-in-law thought that he was joking.[26] As dawn broke, the angels urged Lot to flee with his wife and two remaining daughters, but still he delayed.[27] So out of God's mercy, the men seized Lot, his wife, and daughters and brought them out of the city, telling them to flee for their lives and not to stop or look back anywhere in the plain.[28] But Lot asked them whether he might flee to a little village nearby.[29] The third reading ends here.[30]

Fourth reading – Genesis 19:21–21:4

[edit]In the long fourth reading, the angel replied that he would grant Lot this favor too, and spare that town.[31] The angel urged Lot to hurry there, for the angel could not do anything until he arrived there, and thus the town came to be called Zoar.[32] As the sun rose and Lot entered Zoar, God rained sulfurous fire from heaven on Sodom and Gomorrah and annihilated the entire plain.[33] Lot's wife looked back and turned into a pillar of salt.[34] The next morning, Abraham hurried to the place where he had stood before God and looked down toward Sodom and Gomorrah and saw the smoke rising like at a kiln.[35] Lot was afraid to dwell in Zoar, so he settled in a cave in the hill country with his two daughters.[36] The older daughter told the younger that their father was old, and there was not a man on earth with whom to have children, so she proposed that they get Lot drunk and have sex with him so that they might maintain life through their father.[37] That night they made their father drink wine, and the older one lay with her father without his being aware.[38] And the next day the older one persuaded the younger to do the same.[39] The two daughters thus had children by their father, the older one bore a son named Moab who became the father of the Moabites, and the younger bore a son named Ben-ammi who became the father of the Ammonites.[40] A closed portion ends here with the end of chapter 19.[41]

As the reading continues in chapter 20, Abraham settled between Kadesh and Shur.[42] While he was sojourning in Gerar, Abraham said that Sarah was his sister, so King Abimelech had her brought to him, but God came to Abimelech in a dream and told him that taking her would cause him to die, for she was married.[43] Abimelech had not approached her, so he asked God whether God would slay an innocent, as Abraham and Sarah had told him that they were brother and sister.[44] God told Abimelech in the dream that God knew that Abimelech had a blameless heart, and so God had kept him from touching her.[45] God told Abimelech to restore Abraham's wife, since he was a prophet, and he would intercede for Abimelech to save his life, which he would lose if he failed to restore her.[46] Early the next morning, Abimelech told his servants what had happened and asked Abraham what he had done and why he had brought so great a guilt upon Abimelech and his kingdom.[47] Abraham replied that he had thought that Gerar had no fear of God and would kill him because of his wife, and that she was in fact his father's daughter though not his mother's, so he had asked of her the kindness of identifying him as her brother.[48] Abimelech restored Sarah to Abraham, gave him sheep, oxen, and slaves, and invited him to settle wherever he pleased in Abimelech's lands.[49] Abimelech told Sarah that he was giving Abraham a thousand pieces of silver to serve her as vindication before all.[50] Abraham then prayed to God, and God healed Abimelech and the women in his household, so that they bore children, for God had stricken the women with infertility because of Sarah.[51] Another closed portion ends here with the end of chapter 20.[41]

As the reading continues in chapter 21, God took note of Sarah, and she bore Abraham a son as God had predicted, and Abraham named him Isaac.[52] Abraham circumcised Isaac when he was eight days old.[53] The fourth reading ends here.[54]

Fifth reading – Genesis 21:5–21

[edit]In the fifth reading, Abraham was 100 years old when Isaac was born, and Sarah remarked that God had brought her laughter and everyone would laugh with her about her bearing Abraham a child in his old age.[55] Abraham held a great feast on the day that Sarah weaned Isaac.[56] Sarah saw Hagar's son Ishmael playing, and Sarah told Abraham to cast Hagar and Ishmael out, saying that Ishmael would not share in Abraham's inheritance with Isaac.[57] Sarah's words greatly distressed Abraham, but God told Abraham not to be distressed but to do whatever Sarah told him, for Isaac would carry on Abraham's line, and God would make a nation of Ishmael, too.[58] Early the next morning, Abraham placed some bread and water on Hagar's shoulder, together with Ishmael, and sent them away.[59] Hagar and Ishmael wandered in the wilderness of Beersheba, and when the water ran out, she left the child under a bush, sat down about two bowshots away so as not to see the child die, and burst into tears.[60] God heard the cry of the boy, and an angel called to Hagar, saying not to fear, for God had heeded the boy's cry, and would make of him a great nation.[61] Then God opened her eyes to a well of water, and she and the boy drank.[62] God was with Ishmael and he grew up in the wilderness and became a bowman.[63] Ishmael lived in the wilderness of Paran, and Hagar got him an Egyptian wife.[64] The fifth reading and the first open portion end here.[65]

Sixth reading – Genesis 21:22–34

[edit]In the sixth reading, Abimelech and Phicol the chief of his troops asked Abraham to swear not to deal falsely with them.[66] Abraham reproached Abimelech because Abimelech's servants had seized Abraham's well, but Abimelech protested ignorance.[67] Abraham gave Abimelech sheep and oxen and the two men made a pact.[68] Abraham then offered Abimelech seven ewes as proof that Abraham had dug the well.[69] They called the place Beersheba, for the two of them swore an oath there.[70] After they concluded their pact, Abimelech and Phicol returned to Philistia, and Abraham planted a tamarisk and invoked God's name.[71] Abraham lived in Philistia a long time.[72] The sixth reading and the second open portion end here with the end of chapter 21.[73]

Seventh reading – Genesis chapter 22

[edit]In the seventh reading, which coincides with chapter 22,[74] sometime later, God tested Abraham, directing him to take Isaac to the land of Moriah and offer him there as a burnt offering.[75] Early the next morning, Abraham saddled his donkey and split wood for the burnt offering, and then he, two of his servants, and Isaac set out for the place that God had named.[76] On the third day, Abraham saw the place from afar, and directed his servants to wait with the donkey, while Isaac and he went up to worship and then return.[77] Abraham took the firestone and the knife, put the wood on Isaac, and the two walked off together.[78] When Isaac asked Abraham where the sheep was for the burnt offering, Abraham replied that God would see to the sheep for the burnt offering.[79] They arrived at the place that God had named, and Abraham built an altar, laid out the wood, bound Isaac, laid him on the altar, and picked up the knife to slay him.[80] Then an angel called to Abraham, telling him not to raise his hand against the boy, for now God knew that Abraham feared God, since he had not withheld his son.[81] Abraham looked up and saw a ram caught in a thicket by its horns, so he offered it as a burnt offering in place of his son.[82] Abraham named the site Adonai-yireh.[83] The angel called to Abraham a second time, saying that because Abraham had not withheld his son, God would bless him and make his descendants as numerous as the stars of heaven and the sands on the seashore, and victorious over their foes.[84] All the nations of the earth would bless themselves by Abraham's descendants, because he obeyed God's command.[85] Abraham returned to his servants, and they departed for Beersheba, where Abraham stayed.[86] The third open portion ends here.[87]

As the seventh reading continues with the maftir reading that concludes the parashah,[87] later, Abraham learned that Milcah had borne eight children to his brother Nahor, among whom was Bethuel, who became the father of Rebekah.[88] Nahor's concubine Reumah also bore him four children.[89] The seventh reading, the fourth open portion, chapter 22, and the parashah end here.[87]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

[edit]Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[90]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2025, 2028, 2031 . . . | 2026, 2029, 2032 . . . | 2027, 2030, 2033 . . . | |

| Reading | 18:1–33 | 19:1–20:18 | 21:1–22:24 |

| 1 | 18:1–5 | 19:1–11 | 21:1–4 |

| 2 | 18:6–8 | 19:12–20 | 21:5–13 |

| 3 | 18:9–14 | 19:21–29 | 21:14–21 |

| 4 | 18:15–21 | 19:30–38 | 21:22–34 |

| 5 | 18:22–26 | 20:1–8 | 22:1–8 |

| 6 | 18:27–30 | 20:9–14 | 22:9–19 |

| 7 | 18:31–33 | 20:15–18 | 22:20–24 |

| Maftir | 18:31–33 | 20:15–18 | 22:20–24 |

In inner-Biblical interpretation

[edit]The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[91]

Genesis chapter 18

[edit]In Genesis 6:13, God shared God's purpose with Noah, saying, "I have decided to put an end to all flesh" with the flood, and in an internal dialogue in Genesis 18:17–19, God asked, "Shall I hide from Abraham what I am about to do . . . ?" In Amos 3:7, the prophet Amos reported, "Indeed, my Lord God does nothing without having revealed His purpose to His servants the prophets."

Ezekiel 16:49–50 explains what the "grievous" sin was that Genesis 18:20 reported in Sodom. Ezekiel 16:49–50 says that Sodom's iniquity was pride. Sodom had plenty of bread and careless ease, but Sodom did not help the poor and the needy. The people of Sodom were haughty and committed abomination, so God removed them.

Jeremiah 23:14 condemns the prophets of Jerusalem for becoming like the inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah in that they committed a horrible thing, they committed adultery, they walked in lies, they strengthened the hands of evil-doers, and they did not return from their wickedness.

Lamentations 4:6 judged the iniquity of Jerusalem that lead to the Babylonian captivity as greater than the sin of Sodom that led to its destruction in an instant.

In Genesis 18:25, Abraham asked, "Shall not the Judge of all the earth do justly?" God's role as Judge and God's justice are recurring themes in the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh). In Psalm 9:5, the Psalmist tells God, "You have maintained my right and my cause; You sat upon the throne as the righteous Judge." Psalm 58:12 (58:11 in the KJV) affirms that "there is a God that judges in the earth." And Psalm 94:2 similarly calls God "Judge of the earth." Deuteronomy 10:18 reports that God "executes justice for the fatherless and widow." Psalm 33:5 reports that God "loves righteousness and justice." In Psalm 89:14, the Psalmist tells God, "Righteousness and justice are the foundation of Your throne." Psalm 103:6 says that God "executes righteousness and acts of justice for all who are oppressed"; Psalm 140:13 (140:12 in the KJV) says that God "will maintain the cause of the poor, and the right of the needy"; and Psalm 146:7 says that God "executes justice for the oppressed." And Isaiah 28:17, quotes God saying, "I will make justice the line, and righteousness the plummet." Steven Schwarzschild concluded in the Encyclopaedia Judaica that "God's primary attribute of action . . . is justice" and "Justice has widely been said to be the moral value which singularly characterizes Judaism."[92]

Genesis chapter 19

[edit]Judges 19 tells a story parallel in many regards to that of Lot and the men of Sodom in Genesis 19:1–11.

Genesis chapter 22

[edit]Nehemiah 9:8 interpreted God's test of Abraham in Genesis 22 as a test of Abraham's faith, saying to God, "You found his heart faithful before You."

2 Chronicles 3:1 reports that Solomon built the Temple on Mount Moriah, the place to which God sent Abraham in Genesis 22:1–2.

God's blessing to Abraham in Genesis 22:18 that "All the nations of the earth shall bless themselves by your descendants" parallels God's blessing to Abraham in Genesis 12:3 that "all the families of the earth shall bless themselves by you," and is paralleled by God's blessing to Jacob in Genesis 28:14 that "All the families of the earth shall bless themselves by you and your descendants," and is fulfilled by Balaam's request in Numbers 23:10 to share Israel's fate.[93]

In Genesis 22:17, God promised that Abraham's descendants would as numerous as the stars of heaven and the sands on the seashore. Similarly, in Genesis 15:5, God promised that Abraham's descendants would be as numerous as the stars of heaven. In Genesis 26:4, God reminded Isaac that God had promised Abraham that God would make his heirs as numerous as the stars. In Genesis 32:13, Jacob reminded God that God had promised that Jacob's descendants would be as numerous as the sands. In Exodus 32:13, Moses reminded God that God had promised to make the Patriarchs’ descendants as numerous as the stars. In Deuteronomy 1:10, Moses reported that God had multiplied the Israelites until they were then as numerous as the stars. In Deuteronomy 10:22, Moses reported that God had made the Israelites as numerous as the stars. And Deuteronomy 28:62 foretold that the Israelites would be reduced in number after having been as numerous as the stars.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

[edit]The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[94]

Genesis chapters 12–23

[edit]The second century BCE Book of Jubilees reported that Abraham endured ten trials and was found faithful and patient in spirit. Jubilees listed eight of the trials: (1) leaving his country, (2) the famine, (3) the wealth of kings, (4) his wife taken from him, (5) circumcision, (6) Hagar and Ishmael driven away, (7) the binding of Isaac, and (8) buying the land to bury Sarah.[95]

Genesis chapter 19

[edit]Josephus taught that Lot entreated the angels to accept lodging with him because he had learned to be a generous and hospitable man by imitating Abraham.[96]

The Wisdom of Solomon held that Wisdom delivered the "righteous" Lot, who fled from the wicked who perished when the fire came down on the five cities.[97]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

[edit]The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[98]

Genesis chapter 18

[edit]The Mishnah taught that Abraham suffered ten trials and withstood them all, demonstrating how great was Abraham's love for God.[99] The Avot of Rabbi Natan taught[100] that two trials were at the time he was bidden to leave Haran,[101] two were with his two sons,[102] two were with his two wives,[103] one was in the wars of the Kings,[104] one was at the covenant between the pieces,[105] one was in Ur of the Chaldees (where, according to a tradition, he was thrown into a furnace and came out unharmed[106]), and one was the covenant of circumcision.[107] Similarly, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer counted as the 10 trials (1) when Abraham was a child and all the magnates of the kingdom and the magicians sought to kill him, (2) when he was put into prison for ten years and cast into the furnace of fire, (3) his migration from his father's house and from the land of his birth, (4) the famine, (5) when Sarah his wife was taken to be Pharaoh's wife, (6) when the kings came against him to slay him, (7) when (in the words of Genesis 17:1) "the word of the Lord came to Abram in a vision," (8) when Abram was 99 years old and God asked him to circumcise himself, (9) when Sarah asked Abraham (in the words of Genesis 21:10) to "Cast out this bondwoman and her son," and (10) the binding of Isaac.[108] And the Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael taught that Abraham inherited both this world and the World To Come as a reward for his faith, as Genesis 15:6 says, "And he believed in the Lord."[109]

Rabbi Hama son of Rabbi Ḥanina taught that visiting the infirm (as God did in Genesis 18:1) demonstrates one of God's attributes that humans should emulate. Rabbi Hama asked what Deuteronomy 13:5 means in the text, "You shall walk after the Lord your God." How can a human being walk after God, when Deuteronomy 4:24 says, "[T]he Lord your God is a devouring fire"? Rabbi Hama explained that the command to walk after God means to walk after the attributes of God. As God clothes the naked—for Genesis 3:21 says, "And the Lord God made for Adam and for his wife coats of skin and clothed them"—so should we also clothe the naked. God visited the sick—for Genesis 18:1 says, "And the Lord appeared to him by the oaks of Mamre" (after Abraham was circumcised in Genesis 17:26)—so should we also visit the sick. God comforted mourners—for Genesis 25:11 says, "And it came to pass after the death of Abraham, that God blessed Isaac his son"—so should we also comfort mourners. God buried the dead—for Deuteronomy 34:6 says, "And He buried him in the valley"—so should we also bury the dead.[110] Similarly, the Sifre on Deuteronomy 11:22 taught that to walk in God's ways means to be (in the words of Exodus 34:6) "merciful and gracious."[111]

Reading the instructions for inaugurating the Tabernacle in Leviticus 9:4, "And [take] an ox and a ram for peace-offerings . . . for today the Lord will appear to you," Rabbi Levi taught that God reasoned that if God would thus reveal God's Self to and bless him who sacrificed an ox and a ram for God's sake, how much more should God reveal God's Self to Abraham, who circumcised himself for God's sake. Consequently, Genesis 18:1 reports, "And the Lord appeared to him [Abraham]."[112]

Rabbi Leazar ben Menahem taught that the opening words of Genesis 18:1, "And the Lord appeared," indicated God's proximity to Abraham. Rabbi Leazar taught that the words of Proverbs 15:29, "The Lord is far from the wicked," refer to the prophets of other nations. But the continuation of Proverbs 15:29, "He hears the prayer of the righteous," refers to the prophets of Israel. God appears to nations other that Israel only as one who comes from a distance, as Isaiah 39:3 says, "They came from a far country to me." But in connection with the prophets of Israel, Genesis 18:1 says, "And the Lord appeared," and Leviticus 1:1 says, "And the Lord called," implying from the immediate vicinity. Rabbi Ḥaninah compared the difference between the prophets of Israel and the prophets of other nations to a king who was with his friend in a chamber separated by a curtain. Whenever the king desired to speak to his friend, he folded up the curtain and spoke to him. But God speaks to the prophets of other nations without folding back the curtain. The Rabbis compared it to a king who has a wife and a concubine; to his wife he goes openly, but to his concubine he repairs with stealth. Similarly, God appears to non-Jews only at night, as Numbers 22:20 says, "And God came to Balaam at night," and Genesis 31:24 says, "And God came to Laban the Aramean in a dream of the night."[113]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that God was revealed to all the prophets in a vision, but to Abraham God was revealed in a revelation and a vision. Genesis 18:1 tells of the revelation when it says, “And the Lord appeared to him by the oaks of Mamre.” And Genesis 15:1 tells of the vision when it says, “After these things the word of the Lord came to Abram in a vision.”[114]

A midrash interpreted the words of Job 19:26, "And when after my skin thus is destroyed (נִקְּפוּ, nikkefu), then through my flesh shall I see God," to allude to Abraham. According to the midrash, Abraham reasoned that after he circumcised himself, many proselytes flocked (hikkif) to attach themselves to the covenant, and it was thus because Abraham did so that God revealed God's Self to Abraham, as Genesis 18:1 reports, "And the Lord appeared to him." (And thus through circumcision performed on his flesh did Abraham come to see God.)[115]

A midrash interpreted Song of Songs 2:9, "My beloved is like a gazelle or a young hart; behold, he stands behind our wall," to apply to God's Presence in the synagogue. The midrash read the words, "behold, He stands behind our wall," to allude to the occasion in Genesis 18:1 when God came to visit Abraham on the third day after Abraham's circumcision. Genesis 18:1 says, "And the Lord appeared to him by the terebinths of Mamre, as he sat (יֹשֵׁב, yoshev) . . . ." The word for "he sat" is in a form that can be read yashav, the letter vav being omitted, as though it read that Abraham was sitting before he saw God, but on seeing God, he wanted to stand up. But God told him to sit, as Abraham would serve as a symbol for his children, for when his children would come into their synagogues and houses of study and recite the Shema, they would be sitting down and God's Glory would stand by. To support this reading, the midrash cited Psalm 82:1, "God stands in the congregation of God."[116]

Rabbi Isaac taught that God reasoned that if God said in Exodus 20:21, "An altar of earth you shall make to Me [and then] I will come to you and bless you," thus revealing God's Self to bless him who built an altar in God's name, then how much more should God reveal God's Self to Abraham, who circumcised himself for God's sake. And thus, "the Lord appear to him."[117]

A midrash interpreted the words of Psalm 43:36, "Your condescension has made me great," to allude to Abraham. For God made Abraham great by allowing Abraham to sit (on account of his age and weakness after his circumcision) while the Shekhinah stood, as Genesis 18:1 reports, "And the Lord appeared to him in the plains of Mamre, as he sat in the tent door."[118]

A baraita taught that in Genesis 18:1, "in the heat of the day" meant the sixth hour, or exactly midday.[119]

Rav Judah said in Rav's name that Genesis 18:1–3 showed that hospitality to wayfarers is greater than welcoming the Divine Presence. Rav Judah read the words "And he said, 'My Lord, if now I have found favor in Your sight, pass not away'" in Genesis 18:3 to reflect Abraham's request of God to wait for Abraham while Abraham saw to his guests. And Rabbi Eleazar said that God's acceptance of this request demonstrated how God's conduct is not like that of mortals, for among mortals, a lesser person cannot ask a greater person to wait, while in Genesis 18:3, God allowed it.[120]

The Tosefta taught that God rewarded measure for measure Abraham's good deeds of hospitality in Genesis 18:2–16 with benefits for Abraham's descendants the Israelites.[121]

The Gemara identified the "three men" in Genesis 18:2 as the angels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael. Michael came to tell Sarah of Isaac's birth, Raphael came to heal Abraham, and Gabriel came to destroy Sodom. Noting that Genesis 19:1 reports that "the two angels came to Sodom," the Gemara explained that Michael accompanied Gabriel to rescue Lot. The Gemara cited the use of the singular "He" in Genesis 19:25, where it says, "He overthrew those cities," instead of "they overthrew" to demonstrate that a single angel (Gabriel) destroyed the cities.[122]

Noting that in Genesis 18:5, Abraham offered, "And I will fetch a morsel of bread," but Genesis 18:7 reports, "And Abraham ran to the herd," doing much more than he offered, Rabbi Eleazar taught that the righteous promise little and perform much; whereas the wicked promise much and do not perform even little. The Gemara deduced the behavior of the wicked from Ephron, who in Genesis 23:15 said, "The land is worth 400 shekels of silver," but Genesis 23:16 reports, "And Abraham hearkened to Ephron; and Abraham weighed to Ephron the silver, which he had named in the audience of the sons of Heth, 400 shekels of silver, current money with the merchant," indicating that Ephron refused to accept anything but centenaria (which are more valuable than ordinary shekels).[123]

In Genesis 18:5, the heart is refreshed. A midrash catalogued the wide range capabilities of the heart reported in the Hebrew Bible.[124] The heart speaks,[125] sees,[125] hears,[126] walks,[127] falls,[128] stands,[129] rejoices,[130] cries,[131] is comforted,[132] is troubled,[133] becomes hardened,[134] grows faint,[135] grieves,[136] fears,[137] can be broken,[138] becomes proud,[139] rebels,[140] invents,[141] cavils,[142] overflows,[143] devises,[144] desires,[145] goes astray,[146] lusts,[147] can be stolen,[148] is humbled,[149] is enticed,[150] errs,[151] trembles,[152] is awakened,[153] loves,[154] hates,[155] envies,[156] is searched,[157] is rent,[158] meditates,[159] is like a fire,[160] is like a stone,[161] turns in repentance,[162] becomes hot,[163] dies,[164] melts,[165] takes in words,[166] is susceptible to fear,[167] gives thanks,[168] covets,[169] becomes hard,[170] makes merry,[171] acts deceitfully,[172] speaks from out of itself,[173] loves bribes,[174] writes words,[175] plans,[176] receives commandments,[177] acts with pride,[178] makes arrangements,[179] and aggrandizes itself.[180]

The Gemara noted that in Genesis 18:6, Abraham directed Sarah to take flour, "knead it, and make cakes upon the hearth," but then Genesis 18:8 reports, "And he took butter and milk, and the calf," without reporting that Abraham brought any bread to his guests. Ephraim Maksha'ah, a disciple of Rabbi Meir, said in his teacher's name that Abraham ate even unconsecrated food (chullin) only when it was ritually pure, and that day Sarah had her menstrual period (and so the bread that she baked was ritually impure by virtue of this phenomenon that reflected the rejuvenation that was to make the birth of Isaac possible).[123] Similarly, the Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer taught that when the three angels visited Abraham, Abraham ran to meet them and prepare for them a great banquet. He told Sarah to prepare cakes for them, but when Sarah was kneading, she perceived that the manner of women was upon her, so Abraham did not serve his visitors any of the cakes. Rather, Abraham ran to fetch a calf, but the calf fled from him and went into the cave of Machpelah. Abraham chased in after the calf and found Adam and Eve lying there upon their beds. Lights were kindled above them, and a sweet scent was upon them. Abraham consequently sought to get the cave as a burial possession, as Genesis 23 reports.[181]

The Gemara read Genesis 18:9, "And they said to him, 'Where is Sarah your wife?' And he said, 'Behold, she is in the tent,'" to teach us that Sarah was modest (and therefore kept secluded). Rav Judah said in Rav's name that the ministering angels knew that Sarah was in the tent, but they brought out the fact that she was in the tent to make her more beloved to Abraham (by impressing him with her modesty). Rabbi Jose son of Rabbi Ḥanina said that they brought out the fact that she was in the tent to send her the wine-cup of benediction (the wine-cup over which the Grace after Meals is recited and which is shared by all the guests).[123]

The Gemara reported that sages in the Land of Israel (and some said Rabbi Isaac) deduced from Sarah's practice as shown in Genesis 18:9 that while it was customary for a man to meet wayfarers, it was not customary for a woman to do so. The Gemara cited this deduction to support the ruling of Mishnah Yevamot 8:3[182] that while a male Ammonite or Moabite was forbidden from entering the congregation of Israel, an Ammonite or Moabite woman was permitted.[183]

Rabbi Haggai said in Rabbi Isaac's name that all of the Matriarchs were prophets.[184]

At the School of Rabbi Ishmael, it was taught that Genesis 18:12–13 demonstrated how great is the cause of peace, for Sarah said of Abraham in Genesis 18:12, "My lord [Abraham] being old," but when God reported Sarah's statement to Abraham, God reported Sarah to have said, "And I [Sarah] am old," so as to preserve peace between Abraham and Sarah.[185] Similarly, in the Jerusalem Talmud, Rabbi Ḥanina said that Scripture teaches how awful the penumbra of gossip is, for Genesis 18:12–13 speaks evasively to keep the peace between Abraham and Sarah.[186]

Reading "set time" in Genesis 18:14 to mean the next "holy day" (as in Leviticus 23:4) the Gemara deduced that God spoke to Abraham on Sukkot to promise that Isaac would be born on Passover, and that there must have been a leap year that year, as those deductions allow the maximum 7 months between any two holy days.[187]

Ravina asked one of the Rabbis who expounded Aggadah before him for the origin of the Rabbinic saying, "The memory of the righteous shall be for a blessing." The Rabbi replied that Proverbs 10:7 says, "The memory of the righteous shall be for a blessing." Ravina asked from where in the Torah one might derive that teaching. The Rabbi answered that Genesis 18:17 says, "Shall I hide from Abraham that which I am doing?" And right after that mention of Abraham's name, God blessed Abraham in Genesis 18:18, saying, "Abraham shall surely become a great and mighty nation."[188]

Rabbi Eleazar interpreted the words, "All the nations of the earth," in Genesis 18:18 to teach that even those who spend their time on the ships that go from Gaul to Spain (and thus spend very little time on the dry earth) are blessed only for Israel's sake.[189]

The Gemara cited Genesis 18:19 to show that Abraham walked righteously and followed the commandments. Rabbi Simlai taught that God communicated to Moses a total of 613 commandments—365 negative commandments, corresponding to the number of days in the solar year, and 248 positive commandments, corresponding to the number of the parts in the human body. The Gemara taught that David reduced the number of precepts to eleven, as Psalm 15 says, "Lord, who shall sojourn in Your Tabernacle? Who shall dwell in Your holy mountain?—He who (1) walks uprightly, and (2) works righteousness, and (3) speaks truth in his heart; who (4) has no slander upon his tongue, (5) nor does evil to his fellow, (6) nor takes up a reproach against his neighbor, (7) in whose eyes a vile person is despised, but (8) he honors them who fear the Lord, (9) he swears to his own hurt and changes not, (10) he puts not out his money on interest, (11) nor takes a bribe against the innocent." Isaiah reduced them to six principles, as Isaiah 33:15–16 says, "He who (1) walks righteously, and (2) speaks uprightly, (3) he who despises the gain of oppressions, (4) who shakes his hand from holding of bribes, (5) who stops his ear from hearing of blood, (6) and shuts his eyes from looking upon evil; he shall dwell on high." The Gemara explained that "he who walks righteously" referred to Abraham, as Genesis 18:19 says, "For I have known him, to the end that he may command his children and his household after him." Micah reduced the commandments to three principles, as Micah 6:8 says, "It has been told you, o man, what is good, and what the Lord requires of you: only (1) to do justly, and (2) to love mercy, and (3) to walk humbly before your God." Isaiah reduced them to two principles, as Isaiah 56:1 says, "Thus says the Lord, (1) Keep justice and (2) do righteousness." Amos reduced them to one principle, as Amos 5:4 says, "For thus says the Lord to the house of Israel, 'Seek Me and live.'" To this Rav Nahman bar Isaac demurred, saying that this might be taken as: "Seek Me by observing the whole Torah and live." The Gemara concluded that Habakkuk based all the Torah's commandments on one principle, as Habakkuk 2:4 says, "But the righteous shall live by his faith."[190]

The Gemara taught that Genesis 18:19 sets forth one of the three most distinguishing virtues of the Jewish People. The Gemara taught that David told the Gibeonites that the Israelites are distinguished by three characteristics: They are merciful, bashful, and benevolent. They are merciful, for Deuteronomy 13:18 says that God would "show you (the Israelites) mercy, and have compassion upon you, and multiply you." They are bashful, for Exodus 20:17 says "that God's fear may be before you (the Israelites)." And they are benevolent, for Genesis 18:19 says of Abraham "that he may command his children and his household after him, that they may keep the way of the Lord, to do righteousness and justice." The Gemara taught that David told the Gibeonites that only one who cultivates these three characteristics is fit to join the Jewish People.[191]

Rabbi Eleazar taught that from the blessing of the righteous one may infer a curse for the wicked. The Gemara explained that one may see the principle at play in the juxtaposition of Genesis 18:19 and 18:20. For Genesis 18:19 speaks of the blessing of the righteous Abraham, saying, "For I have known him, to the end that he may command." And soon thereafter Genesis 18:20 speaks of the curse of the wicked people of Sodom and Gomorrah, saying, "Truly the cry of Sodom and Gomorrah is great."[192]

The Mishnah taught that some viewed the people of Sodom as embracing a philosophy of "what's mine is mine." The Mishnah taught that there are four types of people: (1) One who says: "What's mine is mine, and what's yours is yours"; this is a neutral type, some say this was the type of Sodom. (2) One who says: "What's mine is yours, and what's yours is mine"; this is an unlearned person. (3) One who says: "What's mine is yours, and what's yours is yours"; this is a pious person. And (4) one who says: "What's mine is mine, and what's yours is mine;" this is a wicked person.[193]

The Tosefta employed verses from the book of Job to teach that the people of Sodom acted arrogantly before God because of the good that God had lavished on them. As Job 28:5–8 says, "As for the land, out of it comes bread ... Its stones are the place of sapphires, and it has dust of gold. That path, no bird of prey knows ... The proud beasts have not trodden it." The people of Sodom reasoned that since bread, silver, gold, precious stones, and pearls came forth from their land, they did not need immigrants to come to Sodom. They reasoned that immigrants came only to take things away from Sodom and thus resolved to forget the traditional ways of hospitality.[194] God told the people of Sodom that because of the goodness that God had lavished upon them, they had deliberately forgotten how things were customarily done in the world, and thus God would make them be forgotten from the world. As Job 28:4 says, "They open shafts in a valley from where men live. They are forgotten by travelers. They hang afar from men, they swing to and fro." As Job 12:5–6 says, "In the thought of one who is at ease, there is contempt for misfortune; it is ready for those whose feet slip. The tents of robbers are at peace, and those who provoke God are secure, who bring their god in their Hand." And so as Ezekiel 16:48–50 says, "As I live, says the Lord God, Sodom your sister has not done, she nor her daughters, as you and your daughters have done. Behold, this was the iniquity of your sister Sodom: pride, plenty of bread, and careless ease was in her and in her daughters; neither did she strengthen the hand of the poor and needy. And they were haughty, and committed abomination before Me; therefore I removed them when I saw it."[195]

Rava interpreted the words of Psalm 62:4, "How long will you imagine mischief against a man? You shall be slain all of you; you are all as a bowing wall, and as a tottering fence." Rava interpreted this to teach that the people of Sodom would cast envious eyes on the wealthy, place them by a tottering wall, push the wall down on them, and take their wealth. Rava interpreted the words of Job 24:16, "In the dark they dig through houses, which they had marked for themselves in the daytime; they know not the light." Rava interpreted this to teach that they used to cast envious eyes on wealthy people and entrust fragrant balsam into their keeping, which they placed in their storerooms. In the evening the people of Sodom would smell it out like dogs, as Psalm 59:7 says, "They return at evening, they make a noise like a dog, and go round about the city." Then they would burrow in and steal the money.[196]

The Gemara told of the victims of the people of Sodom, in the words of Job 24:7, "They (would) lie all night naked without clothing and have no covering in the cold." The Gemara said of the people of Sodom, in the words of Job 24:3, "They drive away the donkey of the fatherless, they take the widow's ox for a pledge." In the words of Job 24:2, "They remove the landmarks; they violently take away flocks and feed them." And the Gemara told of their victims, in the words of Job 21:32, "he shall be brought to the grave, and shall remain in the tomb."[196]

The Gemara told that there were four judges in Sodom, named Shakrai, Shakurai, Zayyafi, and Mazle Dina (meaning "Liar," "Awful Liar," "Forger," and "Perverter of Justice"). If a man assaulted his neighbor's wife and caused a miscarriage, the judges would tell the husband to give his wife to the neighbor so that the neighbor might make her pregnant. If a person cut off the ear of a neighbor's donkey, they would order the owner to give it to the offender until the ear grew again. If a person wounded a neighbor, they would tell the victim to pay the offender a fee for bleeding the victim. A person who crossed over with the ferry had to pay four zuzim, but the person who crossed through the water had to pay eight.[197]

Explaining the words, "the cry of Sodom and Gomorrah is great (rabbah, רָבָּה)," in Genesis 18:20, the Gemara told the story of a certain maiden (ribah) in Sodom who gave some bread to a poor man, hiding it in a pitcher. When the people of Sodom found out about her generosity, they punished her by smearing her with honey and placing her on the city wall, where the bees consumed her. Rav Judah thus taught in Rav's name that Genesis 18:20 indicates that God destroyed Sodom on account of the maiden (ribah).[197]

Rabbi Judah explained the words of Genesis 18:21, "her cry that has come to Me." Noting that Genesis 18:21 does not say "their cry" but "her cry," Rabbi Judah told that the people of Sodom issued a proclamation that anyone who gave a loaf of bread to the poor or needy would be burned. Lot's daughter Pelotit, the wife of a magnate of Sodom, saw a poor man on the street, and was moved with compassion. Every day when she went out to draw water, she smuggled all kinds of provisions to him from her house in her pitcher. The men of Sodom questioned how the poor man could survive. When they found out, they brought Pelotit out to be burned. She cried out to God to maintain her cause, and her cry ascended before the Throne of Glory. And God said (in the words of Genesis 18:21) "I will go down now, and see whether they have done altogether according to her cry that has come to Me."[198]

Reading Abraham's request in Genesis 18:32, "What if ten shall be found there?" a midrash asked, why ten (and not fewer)? The midrash answered, so that there might be enough for a minyan of righteous people to pray on behalf of all the people of Sodom. Alternatively, the midrash said, because at the generation of the Flood, eight righteous people remained (in Noah and his family) and God did not give the world respite for their sake. Alternatively, the midrash said, because Lot thought that there were ten righteous people in Sodom—namely Lot, his wife, his four daughters, and his four sons-in-law (but Lot was apparently mistaken in thinking them righteous). Rabbi Judah the son of Rabbi Simon and Rabbi Ḥanin in Rabbi Joḥanan's name said that ten were required for Sodom, but for Jerusalem even one would have sufficed, as Jeremiah 5:1 says, "Run to and fro in the streets of Jerusalem . . . and seek . . . if you can find a man, if there be any who does justly . . . and I will pardon her." And thus Ecclesiastes 7:27 says, "Adding one thing to another, to find out the account." Rabbi Isaac explained that an account can be extended as far as one man for one city. And thus if one righteous person can be found in a city, it can be saved in the merit of that righteous person.[199]

Did Abraham's prayer to God in Genesis 18:23–32 change God's harsh decree? Could it have? On this subject, Rabbi Abbahu interpreted David's last words, as reported in 2 Samuel 23:2–3, where David reported that God told him, "Ruler over man shall be the righteous, even he who rules through the fear of God." Rabbi Abbahu read 2 Samuel 23:2–3 to teach that God rules humankind, but the righteous rule God, for God makes a decree, and the righteous may through their prayer annul it.[200]

Genesis chapter 19

[edit]A midrash asked why the angels took so long to travel from Abraham's camp to Sodom, leaving Abraham at noon and arriving in Sodom only (as Genesis 19:1 reports) "in the evening." The midrash explained that they were angels of mercy, and thus they delayed, thinking that perhaps Abraham might find something to change Sodom's fate, but when Abraham found nothing, as Genesis 19:1 reports, "the two angels came to Sodom in the evening."[201]

A midrash noted that in Genesis 19:1, the visitors are called "angels," whereas in Genesis 18:2, they were called "men." The midrash explained that earlier, when the Shechinah (the Divine Presence) was above them, Scripture called them men, but as soon as the Shechinah departed from them, they assumed the form of angels. Rabbi Levi (or others say Rabbi Tanḥuma in the name of Rabbi Levi) said that to Abraham, whose spiritual strength was great, they looked like men (as Abraham was as familiar with angels as with men). But to Lot, whose spiritual strength was weak, they appeared as angels. Rabbi Ḥanina taught that before they performed their mission, they were called "men." But having performed their mission, they are referred to as "angels." Rabbi Tanḥuma compared them to a person who received a governorship from the king. Before reaching the seat of authority, the person goes about like an ordinary citizen. Similarly, before they performed their mission, Scripture calls them "men," but having performed their mission, Scripture calls them "angels."[202]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that Lot walked with Abraham and learned Abraham's good deeds and ways. The Sages told that Abraham made for himself a house outside Haran, and received all who entered into or went out from Haran, and gave them food and drink. He encouraged them to acknowledge the God of Abraham as the only One in the universe. When Lot came to Sodom, he did likewise. When the people of Sodom proclaimed that all who help the poor or needy with a loaf of bread would be burnt by fire, Lot became afraid, and did not help the poor by day, but did so by night, as Genesis 19:1 reports, “And the two angels came to Sodom at evening; and Lot sat in the gate of Sodom.” Lot saw the two angels walking in the street of the city, and he thought that they were wayfarers in the land, and he ran to meet them. He invited them to lodge overnight in his house and eat and drink. But the men would not accept this for themselves, so he took them by the hand against their will, and brought them inside his house, as Genesis 19:3 reports, “And he urged them greatly.” All were treated with measure for measure, for just as Lot had taken the angels by the hand without their will and taken them into his house, so they took hold of his hand in Genesis 19:16 and took Lot and his family out of the city, as Genesis 19:16 reports, “But he lingered; and the men laid hold upon his hand.” The angels told Lot and his family not to look behind, for the Shechinah had descended to rain brimstone and fire upon Sodom and Gomorrah. But Lot's wife Edith was stirred with pity for her daughters, who were married in Sodom, and she looked back behind her to see if they were coming after her. And she saw behind the Shechinah, and she became a pillar of salt, as Genesis 19:26 reports, “And his wife looked back from behind him, and she became a pillar of salt.”[203]

The Gemara asked what differed between the incident involving Abraham, where the angels acquiesced immediately to Abraham's request to remain with him, as in Genesis 18:5, they said, “So do, as you have said,” and the incident involving Lot, where the angels first displayed reluctance, as Genesis 19:3 reports, “And he urged them greatly,” only after which the two angels acquiesced. Rabbi Elazar taught that from here we learn that one may decline the request of a lesser person, but not that of a great person.[204]

A midrash expounded on the conversation between Lot and the angels. Expanding on the words, "but before they lay down" in Genesis 19:4, the midrash told that the angels began questioning Lot, inquiring into the nature of the people of the city. Lot replied that in every town there are good people and bad people, but in Sodom the overwhelming majority were bad. Then (in the words of Genesis 19:4) "the men of the city, the men of Sodom, compassed the house round, both young and old," not one of them objecting. And then (in the words of Genesis 19:5) "they called to Lot, and said to him: 'Where are the men that came to you this night? Bring them out to us, that we may know them.'" Rabbi Joshua ben Levi said in the name of Rabbi Padiah that Lot prayed for mercy on the Sodomites' behalf the whole night, and the angels would have heeded him. But when the Sodomites demanded (in the words of Genesis 19:5) "Bring them out to us, that we may know them," that is, for sexual purposes, the angels asked Lot (in the words of Genesis 19:12) "Do you have here (פֹה, poh) any besides?" Which one could read as asking, "What else do you have in your mouth (פֶּה, peh) (to say in their favor)?" Then the angels told Lot that up until then, he had the right to plead in their defense, but thereafter, he had no right to plead for them.[205]

Yochanan bar Nafcha deduced from Genesis 19:15 and 19:23 that one can walk five miles (about 15,000 feet) in the time between the break of dawn and sunrise, as Genesis 19:15 reports that "when the morning arose, then the angels hastened Lot," and Genesis 19:23 reports that "The sun was risen upon the earth when Lot came to Zoar," and Rabbi Ḥaninah said that it was five miles from Sodom to Zoar.[206] But the Gemara noted that as Genesis 19:15 reports that "the angels hastened Lot," they could naturally have covered more ground than a typical person.[207]

The Gemara taught that all names that one could understand as the name of God that the Torah states in connection with Lot are non-sacred and refer to angels, except for that in Genesis 19:18–19, which is sacred. Genesis 19:18–19 says: “And Lot said to them: ‘Please, not so Adonai. Behold your servant has found favor in your eyes, and you have magnified Your mercy that You have performed for me by saving my life.’” The Gemara taught that one can deduce from the context that Lot addressed God, as Lot spoke to the One Who has the capacity to kill and to bring to life.[208]

Reading what Lot told the angel in Genesis 19:20, “Behold, here is this city that is close to run away to and it is small,” the Gemara asked what the word “close” meant, for if it was close in distance, surely the angel could already have seen that. Rather, the word "close" must indicate that its settling was close—that it had been recently settled—and therefore that its sins were few. Thus, Rava bar Meḥasseya said that Rav Ḥama bar Gurya said Rav said that a person should always live in a recently settled city, as its residents will not yet have had the opportunity to commit many sins there. Rabbi Avin taught that the words, "I will escape there please (נָא, na)," in Genesis 19:20 teach that Zoar was newer than other cities. The numerological value of nun alef, the letters of the word נָא, na, is 51, while Sodom was 52 years old. And Rabbi Avin taught that Sodom's tranquil period during which it committed its sins was 26 years, as Genesis 14:4–5 reports: "Twelve years they served Chedorlaomer and thirteen years they rebelled, and in the fourteenth year Chedorlaomer came." The 12 plus 14 years during which they were enslaved were not years of tranquility, leaving only 26 tranquil years during which they were sinful.[209]

Rabbi Eliezer taught that Lot lived in Sodom only on account of his property, but Rabbi Eliezer deduced from Genesis 19:22 that Lot left Sodom empty-handed with the angels telling him, "It is enough that you escape with your life." Rabbi Eliezer argued that Lot's experience proved the maxim (of Mishnah Sanhedrin 10:5[210]) that the property of the wicked, whether inside or outside the town, will be lost.[211]

Rabbi Meir taught that while Genesis 9:11 made clear that God would never again flood the world with water, Genesis 19:24 demonstrated that God might bring a flood of fire and brimstone, as God brought upon Sodom and Gomorrah.[212]

The Mekhilta of Rabbi Ishmael called the east wind "the mightiest of winds" and taught that God used the east wind to punish the people of Sodom, as well as the generation of the Flood, the people of the Tower of Babel, the Egyptians with the plague of the locusts in Exodus 10:13, the Tribes of Judah and Benjamin,[213] the Ten Tribes,[214] Tyre,[215] a wanton empire,[216] and the wicked of Gehinnom.[217]

Rabbi Joshua ben Levi (according to the Jerusalem Talmud) or a baraita in accordance with the opinion of Rabbi Jose the son of Rabbi Ḥanina (according to the Babylonian Talmud) said that the three daily prayers derived from the Patriarchs, and cited Genesis 19:27 for the proposition that Jews derived the morning prayer from Abraham, arguing that within the meaning of Genesis 19:27, "stood" meant "pray," just as it did in Psalm 106:30[218]

Reading the words of Genesis 19:29, "God remembered Abraham and sent out Lot," a midrash asked what recollection was brought up in Lot's favor? The midrash answered that it was the silence that Lot maintained for Abraham when Abraham passed off Sarah as his sister.[219]

Interpreting Genesis 19:29, a midrash taught that (as Mishnah Shabbat rules,[220] if one's house is burning on the Sabbath) one is permitted to save the case of the Torah along with the Torah itself, and one is permitted to save the Tefillin bag along with the Tefillin. This teaches that the righteous are fortunate, and so are those who cleave to them. Similarly, Genesis 8:1 says, "God remembered Noah, and all beasts, and all the animals that were with him in the Ark." And so too, in Genesis 19:29, "God remembered Abraham and sent out Lot."[221]

Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba, citing Rabbi Joḥanan, taught that God rewards even polite speech. In Genesis 19:37, Lot's older daughter named her son Moab ("of my father"), and so in Deuteronomy 2:9, God told Moses, "Be not at enmity with Moab, neither contend with them in battle"; God forbade only war with the Moabites, but the Israelites might harass them. In Genesis 19:38, in contrast, Lot's younger daughter named her son Ben-Ammi (the less shameful "son of my people"), and so in Deuteronomy 2:19, God told Moses, "Harass them not, nor contend with them"; the Israelites were not to harass the Ammonites at all.[222]

Genesis chapter 20

[edit]The Rabbis taught that God appears to non-Jews only in dreams, as God appeared to Abimelech "in a dream of the night" in Genesis 20:3, God appeared to Laban the "in a dream of the night" in Genesis 31:24, and God appeared to Balaam "at night" in Numbers 22:20. The Rabbis taught that God thus appeared more openly to the prophets of Israel than to those of other nations. The Rabbis compared God's action to those of a king who has both a wife and a concubine; to his wife he goes openly, but to his concubine he goes stealthily.[223] And a midrash taught that God's appearance to Abimelech in Genesis 20:3 and God's appearance to Laban in Genesis 31:24 were the two instances where the Pure and Holy One allowed God's self to be associated with impure (idolatrous) people, on behalf of righteous ones.[224]

The Gemara taught that a dream is a sixtieth part of prophecy.[225] Rabbi Hanan taught that even if the Master of Dreams (an angel, in a dream that truly foretells the future) tells a person that on the next day the person will die, the person should not desist from prayer, for as Ecclesiastes 5:6 says, "For in the multitude of dreams are vanities and also many words, but fear God." (Although a dream may seem reliably to predict the future, it will not necessarily come true; one must place one's trust in God.)[226] Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that a person is shown in a dream only what is suggested by the person's own thoughts (while awake), as Daniel 2:29 says, "As for you, Oh King, your thoughts came into your mind upon your bed," and Daniel 2:30 says, "That you may know the thoughts of the heart."[227] When Samuel had a bad dream, he used to quote Zechariah 10:2, "The dreams speak falsely." When he had a good dream, he used to question whether dreams speak falsely, seeing as in Numbers 10:2, God says, "I speak with him in a dream?" Rava pointed out the potential contradiction between Numbers 10:2 and Zechariah 10:2. The Gemara resolved the contradiction, teaching that Numbers 10:2, "I speak with him in a dream?" refers to dreams that come through an angel, whereas Zechariah 10:2, "The dreams speak falsely," refers to dreams that come through a demon.[227]

The Mishnah deduced from the example of Abimelech and Abraham in Genesis 20:7 that even though an offender pays the victim compensation, the offence is not forgiven until the offender asks the victim for pardon. And the Mishnah deduced from Abraham's example of praying for Abimelech in Genesis 20:17 that under such circumstances, the victim would be churlish not to forgive the offender.[228] The Tosefta further deduced from Genesis 20:17 that even if the offender did not seek forgiveness from the victim, the victim must nonetheless seek mercy for the offender.[229]

Rabbi Isaac taught that Abimelech's curse of Sarah caused her son Isaac's blindness (as reported in Genesis 27:1). Rabbi Isaac read the words, "it is for you a covering (kesut) of the eyes," in Genesis 20:16 not as kesut, "covering," but as kesiyat, "blinding." Rabbi Isaac concluded that one should not consider a small matter the curse of even an ordinary person.[230]

Rava derived from Genesis 20:17 and 21:1–2 the lesson that if one has a need, but prays for another with the same need, then God will answer first the need of the one who prayed. Rava noted that Abraham prayed to God to heal Abimelech and his wife of infertility (in Genesis 20:17) and immediately thereafter God allowed Abraham and Sarah to conceive (in Genesis 21:1–2).[231]

Reading Numbers 21:7, the midrash told that the people realized that they had spoken against Moses and prostrated themselves before him and beseeched him to pray to God on their behalf. The midrash taught that then Numbers 21:7 immediately reports, "And Moses prayed," to demonstrate the meekness of Moses, who did not hesitate to seek mercy for them, and also to show the power of repentance, for as soon as they said, "We have sinned," Moses was immediately reconciled to them, for one who is in a position to forgive should not be cruel by refusing to forgive. In the same strain, Genesis 20:17 reports, "And Abraham prayed to God; and God healed" (after Abimelech had wronged Abraham and asked for forgiveness). And similarly, Job 42:10 reports, "And the Lord changed the fortune of Job, when he prayed for his friends" (after they had slandered him). The midrash taught that when one person wrongs another but then says, "I have sinned," the victim is called a sinner if the victim does not forgive the offender. For in 1 Samuel 12:23, Samuel told the Israelites, "As for me, far be it from me that I should sin against the Lord in ceasing to pray for you," and Samuel told them this after they came and said, "We have sinned," as 1 Samuel 12:19 indicates when it reports that the people said, "Pray for your servants . . . for we have added to all our sins this evil."[232]

Genesis chapter 21

[edit]The Rabbis linked parts of the parashah to Rosh Hashanah. The Talmud directs that Jews read Genesis 21 (the expulsion of Hagar) on the first day of Rosh Hashanah and Genesis 22 (the binding of Isaac) on the second day.[233] And in the Talmud, Rabbi Eliezer said that God visited both Sarah and Hannah to grant them conception on Rosh Hashanah. Rabbi Eliezer deduced this from the Bible's parallel uses of the words "visiting" and "remembering" in description of Hannah, Sarah, and Rosh Hashanah. First, Rabbi Eliezer linked Hannah's visitation with Rosh Hashanah through the Bible's parallel uses of the word "remembering." 1 Samuel 1:19–20 says that God "remembered" Hannah and she conceived, and Leviticus 23:24 describes Rosh Hashanah as "a remembering of the blast of the trumpet." Then Rabbi Eliezer linked Hannah's conception with Sarah's through the Bible's parallel uses of the word "visiting." 1 Samuel 2:21 says that "the Lord had visited Hannah," and Genesis 21:1 says that "the Lord visited Sarah."[234]

Reading Genesis 21:2, "And Sarah conceived, and bore Abraham a son (Isaac) in his old age, at the set time (מּוֹעֵד, mo'ed) of which God had spoken to him," Rabbi Huna taught in Hezekiah's name that Isaac was born at midday. For Genesis 21:2 uses the term "set time" (מּוֹעֵד, mo'ed), and Deuteronomy 16:6 uses the same term when it reports, “At the season (מּוֹעֵד, mo'ed) that you came forth out of Egypt." As Exodus 12:51 can be read, "And it came to pass in the middle of that day that the Lord brought the children of Israel out of the land of Egypt," we know that Israel left Egypt at midday, and thus Deuteronomy 16:6 refers to midday when it says "season" (מּוֹעֵד, mo'ed), and one can read "season" (מּוֹעֵד, mo'ed) to mean the same thing in both Deuteronomy 16:6 and Genesis 21:2.[235]

Citing Genesis 21:7, the Pesikta de-Rav Kahana taught that Sarah was one of seven barren women about whom Psalm 113:9 says (speaking of God), "He . . . makes the barren woman to dwell in her house as a joyful mother of children." The Pesikta de-Rav Kahana also listed Rebekah, Rachel, Leah, Manoah's wife, Hannah, and Zion. The Pesikta de-Rav Kahana taught that the words of Psalm 113:9, "He . . . makes the barren woman to dwell in her house," apply, to begin with, to Sarah, for Genesis 11:30 reports that "Sarai was barren." And the words of Psalm 113:9, "a joyful mother of children," apply to Sarah, as well, for Genesis 21:7 also reports that "Sarah gave children suck."[236]

Rav Avira taught (sometimes in the name of Rabbi Ammi, sometimes in the name of Rabbi Assi) that the words "And the child grew, and was weaned (va-yigamal, וַיִּגָּמַל), and Abraham made a great feast on the day that Isaac was weaned" in Genesis 21:8 teach that God will make a great feast for the righteous on the day that God manifests (yigmol) God's love to Isaac's descendants. After they have eaten and drunk, they will ask Abraham to recite the Grace after meals (Birkat Hamazon), but Abraham will answer that he cannot say Grace, because he fathered Ishmael. Then they will ask Isaac to say Grace, but Isaac will answer that he cannot say Grace, because he fathered Esau. Then they will ask Jacob, but Jacob will answer that he cannot, because he married two sisters during both their lifetimes, which Leviticus 18:18 was destined to forbid. Then they will ask Moses, but Moses will answer that he cannot, because God did not allow him to enter the Land of Israel either in life or in death. Then they will ask Joshua, but Joshua will answer that he cannot, because he was not privileged to have a son, for 1 Chronicles 7:27 reports, "Nun was his son, Joshua was his son," without listing further descendants. Then they will ask David, and he will say Grace, and find it fitting for him to do so, because Psalm 116:13 records David saying, "I will lift up the cup of salvation, and call upon the name of the Lord."[237]

The Gemara cited Genesis 21:12 to teach that Sarah was one of seven prophetesses who prophesied to Israel and neither took away from nor added anything to what is written in the Torah. (The other prophetesses were Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Huldah, and Esther.) The Gemara established Sarah's status as a prophetess by citing the words, "Haran, the father of Milkah and the father of Yiscah," in Genesis 11:29. Rabbi Isaac taught that Yiscah was Sarah. Genesis 11:29 called her Yiscah (יִסְכָּה) because she discerned (saketah) by means of Divine inspiration, as Genesis 21:12 reports God instructing Abraham, "In all that Sarah says to you, hearken to her voice." Alternatively, Genesis 11:29 called her Yiscah because all gazed (sakin) at her beauty.[238]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told that Ishmael cast himself beneath thorns in the wilderness, so that he might get some moisture, and called out to the God of his father Abraham to take away his soul, so that he would not have to die of thirst. And God was entreated, as Genesis 21:17 reports, "God has heard the voice of the lad where he is."[239]

Reading the words "And the angel of God called to Hagar" in Genesis 21:17, a midrash explained that this was for Abraham's sake. While the continuation of Genesis 21:17, "God has heard the voice of the lad where he is," connotes that this was for Ishmael's own sake, for a sick people's prayers on their own behalf are more efficacious than those of anyone else.[240]

The Gemara taught that if one sees Ishmael in a dream, then God hears that person's prayer (perhaps because the name "Ishmael" derives from "the Lord has heard" in Genesis 16:11, or perhaps because "God heard" (yishmah Elohim, יִּשְׁמַע אֱלֹהִים) Ishmael's voice in Genesis 21:17).[241]

Rabbi Isaac said that Heaven judges people only on their actions up to the time of judgment, as Genesis 21:17 says, "God has heard the voice of the lad as he is there."[242] Similarly, reading the words "where he is" in Genesis 21:17, Rabbi Simon told that the ministering angels hastened to indict Ishmael, asking whether God would bring up a well for one who (through his descendants) would one day slay God's children (Israelites) with thirst. God demanded what Ishmael was at that time. The angels answered that Ishmael (at that time) was righteous. God replied that God judges people only as they are at the moment.[240]

Rabbi Benjamin ben Levi and Rabbi Jonathan ben Amram both read the words of Genesis 21:19, "And God opened her eyes and she saw," to teach that all may be presumed to be blind, until God enlightens their eyes.[240]

Rabbi Simeon wept that Hagar, the handmaid of Rabbi Simeon's ancestor Abraham's house, was found worthy of meeting an angel on three occasions, while Rabbi Simeon did not meet an angel even once.[243]

Rabbi Tarfon read Genesis 21:21 to associate Mount Paran with the children of Ishmael. Rabbi Tarfon taught that God came from Mount Sinai (or others say Mount Seir) and was revealed to the children of Esau, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "The Lord came from Sinai, and rose from Seir to them," and "Seir" means the children of Esau, as Genesis 36:8 says, "And Esau dwelt in Mount Seir." God asked them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), "You shall do no murder." The children of Esau replied that they were unable to abandon the blessing with which Isaac blessed Esau in Genesis 27:40, "By your sword shall you live." From there, God turned and was revealed to the children of Ishmael, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "He shined forth from Mount Paran," and "Paran" means the children of Ishmael, as Genesis 21:21 says of Ishmael, "And he dwelt in the wilderness of Paran." God asked them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17), "You shall not steal." The children of Ishmael replied that they were unable to abandon their fathers' custom, as Joseph said in Genesis 40:15 (referring to the Ishmaelites' transaction reported in Genesis 37:28), "For indeed I was stolen away out of the land of the Hebrews." From there, God sent messengers to all the nations of the world asking them whether they would accept the Torah, and they asked what was written in it. God answered that it included (in Exodus 20:3 and Deuteronomy 5:7, "You shall have no other gods before me." They replied that they had no delight in the Torah, therefore let God give it to God's people, as Psalm 29:11 says, "The Lord will give strength [identified with the Torah] to His people; the Lord will bless His people with peace." From there, God returned and was revealed to the children of Israel, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "And he came from the ten thousands of holy ones," and the expression "ten thousands" means the children of Israel, as Numbers 10:36 says, "And when it rested, he said, 'Return, O Lord, to the ten thousands of the thousands of Israel.'" With God were thousands of chariots and 20,000 angels, and God's right hand held the Torah, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "At his right hand was a fiery law to them."[244]

The Sifre cited Abraham's reproval of Abimelech in Genesis 21:25 as an example of a tradition of admonition near death. The Sifre read Deuteronomy 1:3–4 to indicate that Moses spoke to the Israelites in rebuke. The Sifre taught that Moses rebuked them only when he approached death, and the Sifre taught that Moses learned this lesson from Jacob, who admonished his sons in Genesis 49 only when he neared death. The Sifre cited four reasons why people do not admonish others until the admonisher nears death: (1) so that the admonisher does not have to repeat the admonition, (2) so that the one rebuked would not suffer undue shame from being seen again, (3) so that the one rebuked would not bear ill will to the admonisher, and (4) so that the one may depart from the other in peace, for admonition brings peace. The Sifre cited as examples of admonition near death: (1) when Abraham reproved Abimelech in Genesis 21:25, (2) when Isaac reproved Abimelech, Ahuzzath, and Phicol in Genesis 26:27, (3) when Joshua admonished the Israelites in Joshua 24:15, (4) when Samuel admonished the Israelites in 1 Samuel 12:34–35, and (5) when David admonished Solomon in 1 Kings 2:1.[245]

Reading the report of Genesis 21:25, "And Abraham reproved Abimelech," Rabbi Jose bar Rabbi Ḥanina taught that reproof leads to love, as Proverbs 9:8 says, "Reprove a wise man, and he will love you." Rabbi Jose bar Ḥanina said that love unaccompanied by reproof is not love. And Resh Lakish taught that reproof leads to peace, and thus (as Genesis 21:25 reports) "Abraham reproved Abimelech." Resh Lakish said that peace unaccompanied by reproof is not peace.[246]

Rav Nachman taught that when Jacob "took his journey with all that he had, and came to Beersheba" in Genesis 46:1, he went to cut down the cedars that Genesis 21:33 reports his grandfather Abraham had planted there.[247]

Genesis chapter 22

[edit]Rabbi Joḥanan, on the authority of Rabbi Jose ben Zimra, asked what Genesis 22:1 means by the word "after" in "And it came to pass after these words, that God did tempt Abraham." Rabbi Joḥanan explained that it meant after the words of Satan, as follows. After the events of Genesis 21:8, which reports that Isaac grew, was weaned, and Abraham made a great feast the day that Isaac was weaned, Satan asked God how it could be that God graciously granted Abraham a child at the age of 100, yet of all that feast, Abraham did not sacrifice one turtledove or pigeon to God. Rather, Abraham did nothing but honor his son. God replied that were God to ask Abraham to sacrifice his son to God, Abraham would do so without hesitation. Straightway, as Genesis 22:1 reports, "God did tempt Abraham."[248]

Rabbi Levi explained the words "after these words" in Genesis 22:1 to mean after Ishmael's words to Isaac. Ishmael told Isaac that Ishmael was more virtuous than Isaac in good deeds, for Isaac was circumcised at eight days (and so could not prevent it), but Ishmael was circumcised at 13 years. Isaac questioned whether Ishmael would incense Isaac on account of one limb. Isaac vowed that if God were to ask Isaac to sacrifice himself before God, Isaac would obey. Immediately thereafter (in the words of Genesis 22:1) "God did prove Abraham."[248]

A midrash taught that Abraham said (beginning with the words of Genesis 22:1 and 22:11) "'Here I am'—ready for priesthood, ready for kingship" (ready to serve God in whatever role God chose), and Abraham attained both priesthood and kingship. He attained priesthood, as Psalm 110:4 says, "The Lord has sworn, and will not repent: 'You are a priest forever after the manner of Melchizedek." And he attained kingship, as Genesis 23:6 says, "You are a mighty prince among us."[249]

Rabbi Simeon bar Abba explained that the word na (נָא) in Genesis 22:2, "Take, I pray (na, נָא) your son," can denote only entreaty. Rabbi Simeon bar Abba compared this to a king who was confronted by many wars, which he won with the aid of a great warrior. Subsequently, he was faced with a severe battle. Thereupon the king asked the warrior, "I pray, assist me in battle, so that people may not say that there was nothing to the earlier battles." Similarly, God said to Abraham, "I have tested you with many trials and you withstood all of them. Now, be firm, for My sake in this trial, so that people may not say that there was nothing to the earlier trials."[248]

The Gemara expanded on Genesis 22:2, explaining that it reports only one side of a dialog. God told Abraham, “Take your son," but Abraham replied, "I have two sons!" God said, "Your only one," but Abraham replied, "Each is the only one of his mother!" God said, "Whom you love," but Abraham replied, "I love them both!" Then God said, "Isaac!" The Gemara explained that God employed all this circumlocution in Genesis 22:2 so that Abraham's mind should not reel under the sudden shock of God's command.[248]

A baraita interpreted Leviticus 12:3 to teach that the whole eighth day is valid for circumcision, but deduced from Abraham's rising "early in the morning" to perform his obligations in Genesis 22:3 that the zealous perform circumcisions early in the morning.[250]

A Tanna taught in the name of Rabbi Simeon ben Eleazar that intense love and hate can cause one to disregard the perquisites of one's social position. The Tanna deduced that love may do so from Abraham, for Genesis 22:3 reports that "Abraham rose early in the morning, and saddled his donkey," rather than allow his servant to do so. Similarly, the Tanna deduced that hate may do so from Balaam, for Numbers 22:21 reports that "Balaam rose up in the morning, and saddled his donkey," rather than allow his servant to do so.[251]

Rabbi Isaac noted that Isaac was 37 years old when Abraham bound him (based on the report of Genesis 23:1 after the binding of Isaac that Sarah died at the age of 127, and Genesis 17:17 and 21:5 report that Sarah was 90 years old when Isaac was born). Rabbi Isaac argued that one cannot bind a 37-year-old without his consent. Rabbi Isaac thus told that when Abraham sought to bind his son Isaac, Isaac expressed concern that he would tremble in fear of the knife and would thereby upset Abraham or perhaps render the slaughter unfit as a valid offering. Therefore, Isaac asked Abraham to bind him well.[252]

The Sifra cited Genesis 22:11, Genesis 46:2, Exodus 3:4, and 1 Samuel 3:10 for the proposition that when God called the name of a prophet twice, God expressed affection and sought to provoke a response.[253] Similarly, Rabbi Hiyya taught that it was an expression of love and encouragement. Rabbi Liezer taught that the repetition indicated that God spoke to Abraham and to future generations. Rabbi Liezer taught that there is no generation that does not contain people like Abraham, Jacob, Moses, and Samuel.[254]

Noting that Isaac was saved on Mount Moriah in Genesis 22:11–12, the Jerusalem Talmud concluded that since Isaac was saved, it was as if all Israel was saved.[255]