Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

West Greenlandic

View on Wikipedia| West Greenlandic | |

|---|---|

| Kalaallisut, Kitaamiisut | |

| Native to | West Greenland Denmark |

| Ethnicity | Kalaallit |

Native speakers | (44,000–52,000 cited 1995)[1] |

Eskaleut

| |

Early forms | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | kala1399 |

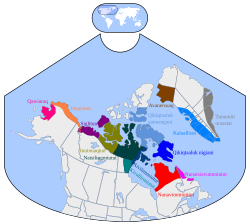

Inuit dialects. West Greenlandic in blue. | |

West Greenlandic is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Kalaallisut (lit. 'language of the Kalaallit'), also known as West Greenlandic (Danish: vestgrønlandsk), is the primary language of Greenland and constitutes the Greenlandic language, spoken by the vast majority of the inhabitants of Greenland, as well as by thousands of Greenlandic Inuit in Denmark proper (in total, approximately 50,000 people).[2] It was historically spoken in the southwestern part of Greenland, i.e. the region around Nuuk.

Tunumiisut and Inuktun are the two other native languages of Greenland, spoken by a small minority of the population. Danish remains an important lingua franca in Greenland and used in many parts of public life, as well as being the main language spoken by Danes in Greenland.

An extinct mixed trade language known as West Greenlandic Pidgin was based on West Greenlandic.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ 44,000 in Greenland, and perhaps 20% more in Denmark. Greenlandic at Ethnologue (16th ed., 2009)

- ^ Peter Schmitter, Sprachtheorien der Neuzeit: Sprachbeschreibung und Sprachunterricht, Narr, 2007, p. 406.

- ^ Silvia Kouwenberg, John Victor Singler (ed.), The Handbook of Pidgin and Creole Studies, Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, West Sussex, p. 172.

West Greenlandic

View on GrokipediaClassification and dialects

Genetic affiliation

West Greenlandic, known to its speakers as Kalaallisut, is classified within the Inuit branch of the Eskimo languages, which form part of the broader Eskimo–Aleut language family. The Eskimo–Aleut family consists of two primary branches: Eskimo, encompassing both Yupik and Inuit languages, and the more divergent Aleut branch.[9] This affiliation places West Greenlandic in close relation to other Inuit varieties spoken across the Arctic, from Alaska and Canada to Greenland. Within Greenland, West Greenlandic represents the dominant dialect, alongside East Greenlandic (Tunumiisut) and North Greenlandic (Inuktun or Avanersuarmiutut), all of which belong to the Inuit dialect continuum that emerged from Thule Inuit migrations around 800–1,000 years ago.[8] These Greenlandic varieties share mutual intelligibility to varying degrees but exhibit distinct phonological and lexical traits due to geographic isolation.[8] The roots of West Greenlandic trace back to Proto-Inuit-Yupik, reconstructed as originating approximately 4,000–5,000 years ago in association with early Arctic migrations, such as the Arctic Small Tool tradition.[10] Divergence into the modern Inuit languages, including the Greenlandic dialects, began around 1,000 years ago during the expansion of Thule-speaking populations across the eastern Arctic.[8] West Greenlandic shares key typological features with other Inuit languages, including polysynthetic word formation—where complex sentences are often expressed in single words—and ergative-absolutive case alignment.[9] These characteristics underscore the family's internal coherence despite regional variations.Internal variation

West Greenlandic, known as Kalaallisut, serves as the prestige dialect of Greenland and forms the foundation for the standardized form of the language used in education, media, and official communications.[8] This central variety, particularly around Nuuk (formerly Godthåb), has become dominant due to historical missionary influences and modern standardization efforts, marginalizing other subdialects while promoting a unified written norm.[8] Within West Greenlandic, several subdialects exhibit minor variations, primarily in pronunciation and vocabulary, though these differences do not significantly impede mutual intelligibility among speakers. The Nuuk subdialect, spoken in the capital area, reflects a blend of neighboring forms due to migration and urbanization, featuring variations in fricative realizations such as a post-alveolar [ʃ] distinct from the alveolar in more southern areas like Paamiut. In contrast, the Sisimiut variety, from the central west coast, preserves more conservative features, such as clearer distinctions in fricative realizations, while the Maniitsoq subdialect to the south shows subtle shifts in consonant gemination after long vowels. Northern subdialects like Upernavik introduce i-dialect traits, including vowel shifts (e.g., /u/ to /i/) and nasalization of intervocalic /g/ and /r/, alongside vocabulary items influenced by isolation. These variations are largely phonological and lexical, with examples including regional terms for everyday objects, but they remain mutually intelligible within the West Greenlandic continuum.[8] West Greenlandic maintains high mutual intelligibility with other West subdialects but faces challenges with East Greenlandic (Tunumiisut), where phonological innovations like asymmetric vowel harmony—absent in West varieties—create barriers, alongside considerable vocabulary replacement due to historical factors.[8] West speakers often struggle with Tunumiisut comprehension, though East speakers fare better due to exposure to Kalaallisut through media.[8] Rapid urbanization, particularly in Nuuk where over 20% of residents (as of 2023) are born outside Greenland, has accelerated dialect leveling, reducing regional distinctions through increased contact and language mixing.[11] Younger speakers exhibit morphosyntactic shifts, such as declining use of relative case marking and a preference for antipassive constructions with fixed SOV order, leading to shorter, more analytic forms influenced by Danish and English. This leveling promotes a homogenized urban variety, diminishing traditional subdialect markers like complex case distinctions (e.g., merging ablative -mit and locative -mi).[11]Historical development

Origins and early history

The ancestors of West Greenlandic speakers trace their linguistic roots to the Proto-Inuit language, which diverged from Central Alaskan Yupik approximately 2,000 years ago, marking a key split within the Eskimoan branch of the Eskimo-Aleut family.[12] This divergence likely occurred amid early population movements in Alaska, where Proto-Inuit speakers developed distinct phonological and morphological features suited to their expanding cultural practices.[12] Linguistic evidence, including shared vocabulary for basic kinship terms and environmental concepts, indicates that Proto-Inuit maintained relative uniformity as communities adapted to coastal and inland Arctic lifeways.[13] Around 1000 AD, the Thule culture—direct forebears of modern Inuit peoples, including West Greenlanders—emerged in coastal Alaska and initiated a rapid eastward migration across the North American Arctic, reaching northwestern Greenland by the late 12th to early 13th centuries.[12] These migrants carried the Proto-Inuit language, which formed the basis for what would evolve into West Greenlandic, with archaeological sites in the Ruin Island phase providing evidence of their arrival and settlement along Greenland's west coast.[13] The swift pace of this expansion, driven by advanced whaling technologies and umiak boats, preserved much of the language's core structure while allowing local dialects to emerge.[12] Adaptation to Greenland's harsh Arctic environment profoundly influenced the early lexicon of Proto-Inuit in the region, incorporating specialized terms for sea mammal hunting, such as those for bowhead whales and narwhals, as well as descriptors for sea ice formations, extreme weather patterns, and extended kinship networks essential for communal survival.[12] These lexical developments reflected the Thule people's shift from previous Dorset culture influences, emphasizing maritime subsistence strategies that demanded precise nomenclature for navigation and resource management.[13] Prior to any written records, the language and cultural knowledge of early West Greenlandic speakers were preserved through rich oral traditions, including myths recounting migration journeys, epic songs detailing hunting exploits, and genealogical narratives that reinforced social bonds and environmental wisdom.[14] These verbal arts, performed in communal settings, ensured the transmission of linguistic nuances and historical memory across generations, with themes of human-animal relations and cosmic balance central to pre-colonial Inuit worldview in Greenland.[12]Colonial period and standardization

The Danish-Norwegian colonization of Greenland began in 1721 when the Norwegian missionary Hans Egede established the first permanent European settlement at Godthåb (now Nuuk), marking the introduction of written records for West Greenlandic. Egede, seeking to convert the Inuit population, learned the language and documented its basic features in his 1729 work Det Gronlands Nye Perlustration (later expanded as A Description of Greenland in 1745), which included the first Greenlandic-Danish vocabulary list and rudimentary grammatical observations, laying the groundwork for linguistic documentation in a previously oral tradition.[15][16] Bible translations played a central role in preserving and disseminating West Greenlandic during the 18th and 19th centuries, serving as primary literary texts amid colonial missionary activities. Starting with partial New Testament translations in the 1740s by Paul Egede, efforts continued with Otto Fabricius and others, culminating in full Bible editions by the early 19th century, involving collaboration between Danish Lutherans, German Moravians, and Greenlandic catechists; between 1750 and 1850 alone, at least twenty versions were published, enhancing literacy and standardizing religious terminology in the language.[17][15] Standardization advanced significantly with Samuel Kleinschmidt's 1851 Grammatik der grönlandischen Sprache, a comprehensive grammar that introduced a phonemically precise orthography for West Greenlandic, incorporating special characters to represent uvular consonants like /q/ and /ʁ/, which distinguished the dialect from European languages. This system, though complex due to its detailed phonetic notations and lengthy morphological analyses, became the basis for official writing until 1973, facilitating schoolbooks, periodicals like Atuagaqdlitut (from 1861), and further Bible revisions that solidified the language's written form.[18][15] In 1953, Greenland's status shifted from colony to Danish county under the revised Danish constitution, designating Danish as the primary administrative and educational language, which intensified cultural assimilation policies known as "Danification" and marginalized West Greenlandic in official domains. This prompted 20th-century linguistic resistance, including grassroots movements and advocacy by intellectuals who viewed the policy as a threat to cultural extinction, culminating in the 1979 Home Rule Act that promoted "Greenlandification" and restored Greenlandic's official status.[15][19]Geographic distribution and speakers

Regions of use

West Greenlandic, also known as Kalaallisut, is primarily spoken along the western coast of Greenland, extending from the area around Nuuk (formerly Godthåb) southward to Paamiut and northward to Upernavik. This core region encompasses the three main subdialects of West Greenlandic: the central prestige variety centered on Nuuk, the northern subdialect from Upernavik to Uummannaq, and the southern subdialect from Paamiut to Qaqortoq.[8] The language also maintains a presence among Greenlandic immigrant communities in Denmark, where an estimated 15,000 to 17,000 Greenlanders reside, primarily in urban areas like Copenhagen, including several thousand speakers who maintain Kalaallisut as a heritage language alongside Danish. These communities reflect historical ties between Greenland and Denmark.[20][4] In East Greenland, West Greenlandic sees limited everyday use due to significant dialect barriers with the local Tunumiisut variety; however, the standard West Greenlandic form serves as the basis for nationwide education, media, and official communication, promoting linguistic unity across the island.[21] Nuuk represents the primary urban hub for West Greenlandic speakers, housing approximately one-third of Greenland's total population and serving as the political, economic, and cultural center where the language is most prominently used in daily life and administration.[22]Speaker demographics

West Greenlandic, also known as Kalaallisut, is spoken by an estimated 50,000 people worldwide, primarily as a native language in Greenland and among the diaspora in Denmark.[3] This figure represents updates from earlier estimates, such as around 44,000 speakers in Greenland documented in 1995, reflecting gradual growth tied to population increases but stable linguistic transmission within core communities.[23] Approximately 85-90% of Greenland's population, totaling about 56,800 residents as of 2025, uses the language, with the majority being native speakers concentrated in the west coast regions.[3][24] Among the Kalaallit, the Inuit majority comprising over 88% of Greenland's population, proficiency in West Greenlandic remains high, serving as the primary first language for most individuals, particularly in rural western areas where near-universal use persists across generations.[3] This strong domestic vitality contrasts with challenges abroad, where an estimated 15,000-17,000 Kalaallit live in Denmark as of 2025; however, fluency among younger diaspora members has declined due to historical and ongoing assimilation pressures, including educational systems prioritizing Danish and limited institutional support for Greenlandic maintenance, with only around 7,000-10,000 maintaining fluency.[20][25][4] Despite its designation as Greenland's official language since 2009, West Greenlandic is classified as vulnerable by UNESCO, indicating risks from external influences like urbanization and migration, though intergenerational transmission in home settings continues robustly within Greenland.[3][26]Phonology

Consonants

West Greenlandic features an inventory of 14 consonant phonemes, comprising four stops, four fricatives, three nasals, one lateral, and two approximants, with geminates (long consonants) forming phonemic contrasts in intervocalic positions.[27] The stops are all voiceless and unaspirated: bilabial /p/, alveolar /t/, velar /k/, and uvular /q/, with no voiced stop phonemes in the native system; aspiration is minimal and non-contrastive across these stops.[28] Fricatives include alveolar /s/, marginal labiodental /f/ (often from Danish loanwords), velar /ɣ/, and uvular /ʁ/, while nasals occur at bilabial /m/, alveolar /n/, and velar /ŋ/.[27] A distinctive feature of the system is the presence of uvular articulations, which contrast with velar ones: the uvular stop /q/ is realized as a voiceless or pre-uvular [ɢ̥] in some contexts, and the uvular fricative /ʁ/ (realized as [ʁ]) appears intervocalically, distinguishing it from the velar /k/ and /ɣ/.[28] The lateral is alveolar /l/, and approximants include labiodental /v/ (with allophones ranging from to bilabial [β] or approximant , varying by speaker age and dialect) and palatal /j/.[27] The uvular /ʁ/ is a fricative, realized as long [χː] in geminated form.[28] Geminates are phonemically distinct from singletons for most consonants (e.g., /pp/ vs. /p/, /mm/ vs. /m/), typically realized as voiceless obstruent or nasal longs intervocalically, with continuants like /v/ and /l/ showing voiceless fricative allophones in geminate position (e.g., /vv/ as [ff], /ll/ as [ɬɬ]).[27] Consonant clusters are rare and subject to regressive assimilation, often resulting in geminates or homorganic sequences, but the underlying phonemic distinctions remain clear.[28]| Place/Manner | Bilabial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | p | t | k | q | |

| Fricatives | (f) | s | ɣ | ʁ | |

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | ||

| Lateral | l | ||||

| Approximants | v | j |

Vowels and prosody

West Greenlandic features a simple vowel inventory consisting of three basic phonemes: /i/, /u/, and /a/. Each of these vowels occurs in short and long forms, yielding a total of six phonemic vowels: /i/, /iː/, /u/, /uː/, /a/, and /aː/.[29] This system is characteristic of many Inuit languages, where vowel quality is limited but length plays a crucial role in distinguishing meaning.[30] There is one phonemic diphthong, /ai/, which occurs only word-finally; other vowel sequences are treated as hiatus or resolved through assimilation rules such as the a-rule, which reduces combinations like /au/ to /aː/.[1] Vowel length is phonemically contrastive, often creating minimal pairs that alter lexical or grammatical interpretations. For instance, /sala/ ('wave') contrasts with /saːla/ ('he stirs it'), demonstrating how the lengthening of the vowel /a/ to /aː/ changes the word's semantics. Long vowels are typically realized as bimoraic, contributing to syllable weight and influencing prosodic structure, while short vowels are monomoraic.[29] Vowels before uvular consonants (/q/, /ʁ/) undergo uvularization: /i/ to [eOrthography

Script and romanization

West Greenlandic, or Kalaallisut, employs a standardized Latin-based orthography adopted in 1973, which replaced earlier systems to better align with phonetic pronunciation and simplify writing for native speakers.[34] This script uses 18 basic letters: A, E, F, G, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, with no diacritics on vowels or consonants in standard usage, though loanwords from Danish may occasionally incorporate Å, Æ, or Ø.[34][1] The orthography is largely phonemic, mapping directly to the language's sounds while accommodating its polysynthetic structure through linear left-to-right writing of complex words formed by morpheme concatenation.[1] Key consonants are represented uniquely to capture uvular and other distinctive phonemes: Q denotes the voiceless uvular stop /q/, as in qimmeq ("dog," pronounced [qimmɜq]); R represents the voiced uvular fricative /ʁ/, often realized as a fricative or approximant, as in arvat ("whale," [ɑʁvɑt̚]); and the digraph NG stands for the velar nasal /ŋ/, as in angut ("man," [ɑŋut̚]).[34][1] Other consonants follow familiar Latin mappings, such as P for /p/, T for /t/ (affricated as [t͡s] before front vowels), K for /k/, and S for /s/.[34] Vowels consist of a core set: A for /a/ (low central, shifting to [ɑ] before uvulars), I for /i/ (high front), U for /u/ (high back), with E indicating a schwa-like /ə/ or contextual variants [ɛ] or [ɜ], and O for /o/ or [ɔ] before uvulars.[1] Vowel length, which is phonemic and contrastive, is marked by doubling: AA for /aː/, II for /iː/, and UU for /uː/, as in nuuk ("Nuuk," [nuːk]) versus nuk (hypothetical short form).[34][1] For precise linguistic transcription, the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) is used in academic contexts, providing equivalents like /q/ for Q, /ʁ/ for R, /ŋ/ for NG, and length marked by ː (e.g., /aː/ for AA).[1] This system ensures readability for long, compound words typical of the language's morphology, without requiring special reading directions beyond standard left-to-right flow.[1]Evolution of the writing system

The writing system for West Greenlandic emerged in the early 18th century through the efforts of Danish missionaries during the colonial period. Hans Egede, arriving in Greenland in 1721, is recognized as the first European to systematically learn and transcribe the language, creating rudimentary written forms for Christian texts by inconsistently adapting letters from the Danish alphabet.[35] These early scripts lacked standardization and often distorted the language's phonological features to fit familiar European conventions, serving primarily evangelical purposes rather than linguistic accuracy.[36] A significant advancement occurred in 1851 when Moravian missionary Samuel Kleinschmidt, building on prior missionary work, introduced the first comprehensive and standardized orthography for West Greenlandic. This system incorporated diacritics for vowel length and quality, as well as unique letters such as ŋ (eng) for the velar nasal and ĸ (kra) to denote the uvular stop /q/, aiming to more faithfully capture the language's complex sound inventory.[37] Kleinschmidt's orthography, detailed in his influential grammar published that year, became the dominant standard for over a century, enabling the production of dictionaries, Bibles, and educational materials, though it was criticized for its complexity and divergence from evolving spoken forms.[18] By the mid-20th century, phonological shifts in spoken West Greenlandic had rendered parts of Kleinschmidt's system outdated, prompting calls for reform. In 1973, Grønlands Landsråd (the Provincial Council of Greenland) approved a major orthographic overhaul, simplifying the script to an 18-letter Latin-based alphabet consisting of A, E, F, G, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, with digraphs like ng for the velar nasal, while eliminating many diacritics and obsolete characters such as ĸ.[34] This reform, which aligned writing more closely with modern pronunciation, dramatically improved literacy rates by reducing the learning burden and was gradually implemented across publications and education. Following the reform, digital adaptations have ensured the orthography's viability in contemporary technology. Post-2000, full integration into the Unicode standard—particularly through Latin Extended-A for characters like ŋ (U+014B)—has supported keyboard layouts, fonts, and software for Greenlandic, enabling seamless use in online communication, digital publishing, and mobile devices without loss of special symbols.Grammar

Nouns and morphology

West Greenlandic nouns exhibit a highly agglutinative morphology, forming complex words through the addition of suffixes that indicate case, number, possession, and definiteness.[1] The language employs eight distinct cases to mark grammatical relations and spatial or semantic roles: absolutive (for intransitive subjects and transitive objects), ergative (for transitive subjects and possessors), equative (for comparisons, as in "like" or "as"), instrumental (for means or instruments), locative (for static location, "in/at"), ablative (for source or origin, "from"), allative (for goal or destination, "to"), and contemporative (for accompaniment or path, "with/along").[38][1] These cases are realized via dedicated suffixes that attach to the noun stem, with forms varying phonologically based on the stem's ending but following consistent patterns; for example, the absolutive singular is typically unmarked (e.g., illu "house"), while the ergative singular uses -p (e.g., illup "of the house" or "his house").[1] Number is distinguished through suffixes, with singular often unmarked and plural marked by endings such as -t or -i (e.g., illu "house" vs. illut "houses").[1] Possession is expressed by a set of person- and number-agreeing suffixes that also convey definiteness, as West Greenlandic lacks articles and grammatical gender.[1] For instance, the third-person singular possessive suffix -p indicates "his/her/its" while marking the noun as definite in ergative contexts (e.g., illup "his house"), whereas first-person singular uses -ga (e.g., illuga "my house").[1] Definiteness is further inflected through these possessive paradigms, where the absence of a possessor suffix leaves the noun indefinite, and specific suffixes like -a for third-person definite in absolutive (e.g., illua "the house").[1] Noun phrases in West Greenlandic are polysynthetic, allowing the incorporation of verbal elements as nominalizers to create complex nominal expressions that function as full noun phrases.[1] Common nominalizing suffixes derive nouns from verbs, such as -ðu q for an intransitive agentive ("one who V-er," e.g., from a verb root meaning "to hunt" yielding a "hunter" noun) or -vik for a locative nominal ("place of V-ing").[1] These constructions enable nouns to embed verbal notions without separate verbs, enhancing the language's capacity for compact expression, as in derivations that combine a nominal root with a verbalized suffix to denote relational or participial concepts.[1]Verbs and syntax

West Greenlandic verbs are highly inflected and central to the language's polysynthetic nature, where a single verb form can incorporate subject, object, and additional semantic elements to form complete sentences.[39] The language features nine verbal moods: four independent moods—indicative for declarative statements, interrogative for yes/no questions, imperative for commands, and optative for wishes or permissions—along with five dependent moods, including the participial for subordinate clauses or relative constructions, contemporative for concurrent actions, causative for reasons or past events, conditional for conditions or future, and iterative for habitual actions.[1][40] For example, the indicative mood marks third-person singular intransitive actions with the suffix -puq, as in iserpuq ("he/she enters"), while the imperative uses -git for second-person singular commands, such as iser-git ("enter!").[39] The participial mood, a dependent form, employs suffixes like -suq to indicate ongoing or relative actions, as in tuqut-suq ("having killed").[40] Tense distinctions in West Greenlandic are not marked by dedicated inflectional categories but are conveyed through derivational affixes, context, or adverbials, allowing for flexible expression of past, present, and future.[40] Future intent is often indicated by suffixes like -ssa- ("shall"), as in taku-riassa-git ("he will want to see"), while past events use forms such as -sima for perfective aspect, exemplified in tuqun-nia-raluar-sima-voat ("they had tried to kill").[39] Present or ongoing actions rely on statal verb bases without additional tense marking, such as uqar-puq ("he says").[40] The language exhibits ergative-absolutive alignment in its syntax, where the subject of an intransitive verb and the object of a transitive verb both take the absolutive case (unmarked), while the agent of a transitive verb is marked ergative with the suffix -p (singular) or -t (plural).[39] This alignment is reflected in verbal agreement: intransitive verbs inflect only for the absolutive subject (internal person), while transitive verbs agree with both the ergative agent (external person) and absolutive patient (internal person) via bipersonal suffixes.[40] For instance, inuit nanuq taku-aat illustrates ergative inuit ("people-ERG"), absolutive nanuq ("bear-ABS"), and the transitive verb taku-aat agreeing in third-person plural ("people saw the bear").[39] Verb suffixes encode person (four categories: first, second, third, and fourth/reflexive) and number (singular or plural), often combining to form portmanteau morphemes that specify both subject and object.[40] In the indicative mood, first-person singular is marked -vunga, as in takuara ("I see it," first singular/third singular), and third-person plural transitive uses -voat, such as taku-voat ("they see it").[39] Object incorporation is a hallmark of polysynthesis, where nouns or nominal elements are suffixed directly to the verb root, obviating separate object noun phrases and enabling one-word sentences; for example, qimmi-qar-puq ("he has a dog," incorporating qimmiq "dog" with -qar- "have").[40] Complex forms like nannun-niuti-kkuminar-tu-rujussu-u-vuq ("he is really good for catching bears") demonstrate how incorporation and multiple suffixes create intricate predicates encoding entire propositions.[39] Basic sentence patterns follow a subject-object-verb (SOV) word order, but this is flexible due to explicit case marking, which disambiguates roles regardless of linear position.[41] For example, puisi piniartup pisaraa ("the hunter caught the seal") places the ergative subject puisi before the absolutive object piniartup, but reordering to object-subject-verb remains interpretable.[40] West Greenlandic lacks definite or indefinite articles, with noun phrases relying on context, demonstratives like una ("this"), or verbal incorporation for specificity.[39]Vocabulary

Core lexicon

The core lexicon of West Greenlandic, known as Kalaallisut, draws predominantly from roots inherited from Proto-Inuit, the ancestral language of the Inuit branch of the Eskimo-Aleut family, reflecting adaptations to Arctic life over millennia. These roots serve as foundational elements, often extended through affixation to create derived forms that convey nuanced meanings. For instance, the noun root *qayaq in Proto-Eskimo corresponds to qajaq 'kayak' in West Greenlandic, a vessel essential for hunting and travel, while *imiq yields imaq 'water' or 'sea', a term central to environmental descriptions. Such cognates highlight the language's deep ties to Proto-Inuit vocabulary, with many basic nouns and verbs tracing back to this common ancestor, as seen in comparative dictionaries of Inuit languages.[42][1] Derivations via affixation enrich these roots, allowing for precise expressions without relying heavily on separate words. Nominal roots can be verbalized, as in qimmeq 'dog' + -qaq 'have a N' yielding qimmeqqaq 'to have a dog', conjugated as qimmeqarpoq 'he/she has a dog'. Verbal roots similarly derive nouns, such as sinik 'sleep' + -tuq 'one who Vs' forming siniktuq 'sleeper'. This polysynthetic structure enables compact phrases, like aullaitingit 'the ones shooting' from aullait 'shoot' + -ngit 'plural nominative', underscoring the lexicon's efficiency in describing actions and states.[1] West Greenlandic exhibits a rich lexicon tailored to Arctic concepts, particularly those involving snow, ice, hunting tools, and kinship, shaped by the region's harsh environment. For snow and ice, contrary to popular myths of hundreds of terms, the language has about two primary roots—qanik 'falling snow/snowflake' and aput 'snow on the ground'—yielding numerous specific derivations through affixation, such as qanik 'snow in the air' or appirneq 'packed snow'. Sea ice terminology is more extensive, with over 70 native terms documenting formations, processes, and hazards crucial for survival; representative examples include siku 'sea ice (general)', allu 'seal breathing hole', inguneq 'pressure ridge', and sikutaq 'small ice floe'. These terms facilitate detailed communication about navigation and weather.[42][43] Hunting tools and practices form another key semantic field, with vocabulary emphasizing marine mammal pursuits like sealing. Tools include tuniitsoq 'harpoon' and umiaq 'large skin boat for whaling', while verbs describe behaviors such as paarmuli 'seal crawls on ice' or uccup 'bearded seal dives', enabling hunters to convey precise observations of animal movements in icy conditions. Kinship terms, inherited from Proto-Inuit, prioritize relational roles in small communities, such as ataata 'father' (from *appaq), anaana 'mother' (from *anaqtaq), erneq 'son/child', and nukaq 'younger sibling', often extended possessively as ataata-p 'my father'.[1][43] Compounding further expands the core lexicon for novel concepts, combining roots with nominalizers like -fik 'place for V-ing' or -vik 'place'. A classic example is atuarfik 'school', derived from atuq- 'use/read' + -arfik 'place of activity', literally 'place for using (knowledge)'. Other compounds include illumikisoq 'small house' from illu 'house' + mikisoq 'small thing' and Kalaallit Nunaat 'Greenland' from Kalaallit 'Greenlanders' + Nunaat 'lands (plural)'. This process maintains semantic transparency while integrating environmental and cultural priorities.[1]Loanwords and neologisms

West Greenlandic has incorporated numerous loanwords from Danish due to centuries of colonial influence beginning in the 18th century, with these borrowings primarily entering the lexicon through trade, administration, and missionary activities. These words are adapted to fit the language's phonological and morphological patterns, often by adding epenthetic vowels or suffixes like -i or -q to resolve consonant clusters or final stops not native to Greenlandic. For instance, the Danish word ost ('cheese') becomes osti, and skole ('school') is rendered as skuli. Other common examples include kavvi ('coffee') from Danish kaffe and iipili ('apple') from æble, illustrating how loanwords undergo vowel shifts and simplifications to align with West Greenlandic's syllable structure.[1] In the post-2000 era, following Greenland's increased autonomy and global connectivity, English has exerted growing influence on West Greenlandic vocabulary, particularly in domains like media, technology, and international trade. Direct borrowings from English, often via Danish intermediaries, include terms such as radio (radio) and televisuni (television, adapted from television). These modern loans reflect the language's adaptation to contemporary concepts, with English words sometimes retaining closer phonetic resemblance than earlier Danish ones due to reduced colonial ties.[44] Neologisms in West Greenlandic are frequently formed through affixation and compounding using native roots, allowing the creation of terms for new concepts without heavy reliance on foreign borrowings. A representative example is qaranngorpoq ('to have a cold'), derived from qar ('throat') combined with affixes indicating possession and state, showcasing the language's polysynthetic nature. Other neologisms employ similar strategies, such as umiarsuaq ('ship') from umiaq ('kayak') plus the augmentative suffix -suaq. This method preserves linguistic purity while expanding the lexicon. Since its establishment in 1998, the Language Secretariat of Greenland (Oqaasileriffik) has played a central role in developing Inuit-based neologisms for modern technology and society, promoting terms derived from traditional roots over direct loans. Notable examples include qarasaasiaq ('computer'), blending elements evoking mechanical function; oqarasuaat ('telephone'), from roots related to conversation; and nittartagaq ('homepage'), incorporating affixes for digital interfaces. These efforts ensure cultural relevance and are disseminated through official glossaries to support education and media.[45][46]Sociolinguistic status

Official recognition

West Greenlandic, known as Kalaallisut, became the official language of Greenland with the enactment of the Self-Government Act on June 12, 2009, which explicitly states in Section 20 that "Greenlandic shall be the official language in Greenland."[47] This legislation marked a significant shift from prior bilingual policies, affirming Kalaallisut's primacy while permitting Danish to be used in official contexts where necessary, such as certain administrative functions.[48] The Act underscores Greenland's autonomy within the Kingdom of Denmark, positioning Kalaallisut as a cornerstone of national identity and governance. In practice, this official status manifests in core state institutions. Parliamentary proceedings in the Inatsisartut are conducted in both Kalaallisut and Danish, with simultaneous interpretation provided, facilitating debates, lawmaking, and official records in the languages.[49] Similarly, the judicial system recognizes both Kalaallisut and Danish as official court languages under the Administration of Justice Act, ensuring accessibility for litigants and proceedings in the indigenous tongue.[50] Public signage, government documents, and official communications further reflect this status, promoting Kalaallisut's visibility in everyday institutional life. Beyond Greenland, Kalaallisut receives some recognition in Denmark as a protected language for Greenlandic immigrant communities through kingdom-wide language support provisions, including in education and services, though implementation varies. Despite these advancements, UNESCO classifies Kalaallisut as vulnerable, attributing this status to the persistent dominance of Danish in higher education, where most advanced programs remain inaccessible in the indigenous language, limiting intergenerational transmission and institutional depth.[51][52]Usage in education and media

In Greenland's primary and lower secondary education system (grades 1-10), West Greenlandic, known as Kalaallisut, serves as the primary medium of instruction, integrating local culture, values, and traditions to foster linguistic and cultural identity among students aged 6-16. In 2024, Greenland adopted a new education strategy for 2024–2030 with a strong focus on promoting Kalaallisut in the school system.[53] Danish is introduced as a second language early on and gains prominence in scientific subjects at upper secondary levels and beyond, where proficiency in Danish is required for advanced studies, often pursued in Denmark.[54] This bilingual approach aligns with national policies emphasizing Kalaallisut while ensuring access to broader educational opportunities.[54] West Greenlandic literature experienced a significant boom starting in the 1970s, accelerated by the 1979 home rule establishment, which encouraged expressions of national identity and anti-colonial sentiment through poetry and prose.[55] Prominent authors like Aqqaluk Lynge contributed to this movement with satirical works such as Ode til Danaiderne (1982), critiquing Danish influences, alongside contemporaries like Moses Olsen and Aqigssiaq Møller, whose protest poetry addressed themes of displacement and cultural preservation.[55] Children's literature in Kalaallisut has also flourished in this era, with books like Mikingama? (2015) by Philipp Winterberg promoting language immersion through engaging stories for young readers. In media, the Greenland Broadcasting Corporation (KNR) delivers radio and television programming primarily in West Greenlandic, including daily news (Qanorooq), cultural shows, and educational content that reaches remote communities across the country.[56] Newspapers such as Sermitsiaq, established in 1958, publish bilingually in Kalaallisut and Danish, covering national and international news to serve both indigenous speakers and bilingual audiences.[57] Since the 2010s, the digital landscape has enhanced West Greenlandic's accessibility through language learning apps and online tools, such as uTalk for conversational practice and GraphoGame Kalaallisut for phonics-based literacy development in children.[58][59] Resources like the OQA website provide free grammar exercises and self-study materials, while the Ilinniusiorfik online dictionary supports vocabulary building for learners worldwide.[60][61]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Category:Greenlandic_terms_borrowed_from_Danish