Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

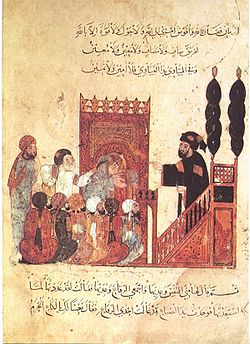

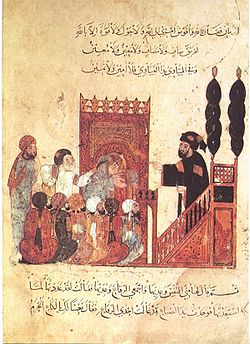

Khatib

View on Wikipedia

In Islam, a khatib or khateeb (Arabic: خطيب khaṭīb) is a person who delivers the sermon (khuṭbah) (literally "narration"), during the Friday prayer and Eid prayers.[1]

The khateeb is usually the prayer leader (imam), but the two roles can be played by different people. The khatib should be knowledgeable of how to lead the prayer and be competent in delivering the speech (khutba) however there are no requirements of eligibility to become a khatib beyond being an Adult Muslim. Some Muslims believe the khatib has to be male but women do lead Friday prayers in number of places.

Women may be khateebahs. Edina Leković gave the inaugural khutba at the Women's Mosque in California, United States, in 2015.[2][3]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hirschkind, Charles (2006). The Ethical Soundscape. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231138185. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ Street, Nick (3 February 2015). "First all-female mosque opens in Los Angeles". Al-Jazeera. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ^ Lekovic, Edina (2015-06-26). "How I became The Women's Mosque of America's first khateebah - altM". altM. Archived from the original on 2018-08-29. Retrieved 2017-06-30.