Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Dargah

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

A Sufi shrine or dargah (Persian: درگاه dargâh or درگه dargah, Turkish: dergâh, Hindustani: dargāh दरगाह درگاہ, Bengali: দরগাহ dôrgah) is a shrine or tomb built over the grave of a revered religious figure, often a Sufi saint or dervish. Sufis often visit the shrine for ziyarat, a term associated with religious visitation and pilgrimages. Dargahs are often associated with Sufi eating and meeting rooms and hostels, called khanqah or hospices. They usually include a mosque, meeting rooms, Islamic religious schools (madrassas), residences for a teacher or caretaker, hospitals, and other buildings for community purposes.

The same structure, carrying the same social meanings and sites of the same kinds of ritual practices, is called maqam in the Arabic-speaking world.

Dargah today is considered to be a place where saints prayed and mediated (their spiritual residence). The shrine is modern day building which encompasses of actual dargah as well but not always.

Etymology

[edit]Dargah is derived from a Persian word which literally means "portal" or "threshold."[1] The Persian word is a composite of "dar (در)" meaning "door, gate" and "gah (گاه)" meaning "place". It may have a connection or connotation with the Arabic word "darajah (دَرَجَة)" meaning "stature, prestige, dignity, order, place" or may also mean "status, position, rank, echelon, class". Some Sufi and other Muslims believe that dargahs are portals by which they can invoke the deceased saint's intercession and blessing (as per tawassul, also known as dawat-e qaboor[2][Persian: da‘wat-i qabũrدعوتِ قبور, "invocations of the graves or tombs"] or ‘ilm-e dawat [Persian: ‘ilm-i da‘wat عِلمِ دعوت, "knowledge of invocations"]). Still others hold a less important view of dargahs, and simply visit as a means of paying their respects to deceased pious individuals or to pray at the sites for perceived spiritual benefits.

However, dargah is originally a core concept in Islamic Sufism and holds great importance for the followers of Sufi saints. Many Muslims believe their wishes are fulfilled after they offer prayer or service at a dargah of the saint they follow. Devotees tie threads of mannat (Persian: منّت, "grace, favour, praise") at dargahs and contribute to langar and pray at dargahs.

Over time, musical offerings of dervishes and sheikhs in the presence of the devout at these shrines, usually impromptu or on the occasion of Urs, gave rise to musical genres like Qawwali and Kafi, wherein Sufi poetry is accompanied by music and sung as an offering to a murshid, a type of Sufi spiritual instructor. Today they have become a popular form of music and entertainment throughout South Asia, with exponents like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Abida Parveen taking their music to various parts of the world.[3][4]

Throughout the non-Arab Muslim world

[edit]Sufi shrines are found in many Muslim communities throughout the world and are called by many names. The term dargah is common in the Persian-influenced Islamic world, notably in Iran, Turkey and South Asia.[5]

In South Africa, the term is used to describe shrines in the Durban area where there is a strong Indian presence, while the term kramat is more commonly used in Cape Town, where there is a strong Cape Malay culture.[6]

In South Asia, dargahs are often the site of festivals (milad) held in honor of the deceased saint on the anniversary of his death (urs). The shrine is illuminated with candles or strings of electric lights at this time.[7] Dargahs in South Asia, have historically been a place for all faiths since the medieval times; for example, the Ajmer Sharif Dargah was a meeting place for Hindus and Muslims to pay respect and even to the revered Saint Mu'in al-Din Chishti.[8][9]

In China, the term gongbei is usually used for shrine complexes centered around a Sufi saint's tomb.[10]

Worldwide

[edit]There are many active dargahs open to the public worldwide where aspirants may go for a retreat. The following is a list of dargahs open to the public.

- Shrine of Shaykh Abdul Qadir Gilani in Baghdad, Iraq

- Shrine of Khawaja Moinuddin Chishti, Ajmer Sharif Dargah, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India

- Shrine of Ahmad Ullah Maizbhandari in Chittagong, Bangladesh

- Shrine of Syed Shah Wilayat Naqvi, Amroha, India

- Shrine of Lal Shahbaz Qalandar in Sehwan Sharif, Pakistan

- Shrine of Sultan ul Arifeen Hazrat Syed Rakhyal Shah Sufi AL Qadri in Dargah Fateh Pur Sharif Gandawah Balochistan Pakistan

- Shrine of Pir Hadi Hassan Bux Shah Jilani in Duthro Sharif, Pakistan

- Shrine of Baba Bulleh Shah in Kasur, Pakistan

- Shrine of Piran Kaliyar in, Roorkee, India.

- Shrine of Murshid Nadir Ali Shah in Sehwan Sharif, Pakistan

- Shrine of Data Ganj Bakhsh Ali al-Hujwiri, Data Darbar, Lahore, Pakistan

- Shrine of Shah Jalal in Sylhet, Bangladesh

- Shrine of Ashraf Jahangir Semnani at Ashrafpur Kichhauchha, Uttar Pradesh, India

- Shrine of Shah Ata in Gangarampur, West Bengal, India[11]

- Shrine of Syed Ibrahim Badshah Shaheed, Erwadi, Tamil Nadu, India

- Shrine of Nagore Dargah in Nagore, Tamil Nadu, India

- Shrine of Sulthan Sikandhar Badhusha Shaheed, Thiruparankundram Dargah, Tamil Nadu, India

- Shrine of Meer Ahmad Ibrahim, Madurai Hazrat Maqbara, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India[12]

- Shrine of Shaykh Nazim Al-Haqqani in Lefka, Cyprus[13]

-

A qawwali performance at the Ajmer Sharif Dargah at Ajmer, India. The dargah houses the grave of Moinuddin Chishti of the Chishti order.

-

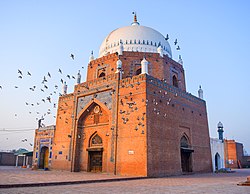

Shrine of Bahauddin Zakariya in Multan, Pakistan. Bahauddin Zakariya was a famous saint of the Suhrawardiyya order.

-

Hazrat Shahul Hameed Qadir Vali Bathusha Nayagam (R.A) in Nagore Dargah

Opposition by other Sunni groups

[edit]The Ahl-i Hadith, Deobandi, Salafi and Wahhabi religious scholars argue against the practice of constructing shrines over graves, and consider it as associating partners with God, which is called shirk.[14] They believe Islamic prophet Muhammad strongly condemned the practice of turning graves into places of worship and even cursed those who did so.[15][16][17][18][19] Although visiting graves is encouraged for the sake of visiting not to worship in the manner that many Sufi go to do ziyarat and make dua with the intercessions of saints which is not rooted within Islam to remember death and the Day of Judgment.[19][20][21]

Sufi defence on permissibility of Dargah

[edit]Sufis, refute such claims on the basis of misquotation of hadith. The hadith "Let there be curse of Allah upon the Jews and the Christians for they have taken the graves of their apostles as places of worship." (Sahih Muslim),[22] is directed towards the disbelievers not the Muslims who took graves as place of worship i.e. they prayed facing towards the graves, this is not the practice of Sufis as they do not take graves as their Qibla (direction). As for constructing structure over grave, it is refuted on the basis that the grave of Prophet Muhammad and the first two Khalifa, Abu Bakr and Umar, itself have a structure over it.

To construct a building, shelter or edifice around the graves of the Auliya Allah (Friends of Allah) and Scholars of Islam or nearby is proven to be permissible from the Quran and practice and rulings of the Sahaba.

Narrating the incident of the People of the Cave [Ashaab-e-Kahf), the Holy Quran states, “The person who was dominant in this matter said, “We shall build a Masjid over the People of the Cave.””– [Surah Kahf. Verse 21]

Imam Fakhr al-Din al-Razi explains the above Quran verse in his famous Tafsir al-Kabeer, "And when Allah said 'Those who prevailed over their affair' this refers to the Muslim ruler or the friends of Ashaab al-Kahf (i.e. believers) or the leaders of town. 'We will surely build a Mosque over them' so that we can worship Allah in it and preserve the relics of companions of the cave due to this mosque." [Tafsir al-Kabeer, 5/475]

Imam Abu al-Walid al-Baji, quotes in his book Al-Muntaqa Sharh al-Muwatta (commentary of Muwatta Imam Malik), "Hadrat Umar built a dome over the grave of Hadrat Zainab bint Jahsh, and Sayyidah Aisha on the grave of her brother Hadrat Abdur-Rahman and Hadrat Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyya on the grave of Hadrat Ibn Abbas. So Whoever has classified building domes to be disliked (Makrooh) has said so if they are built in order to show off." (Imam Badr al-Din al-Ayni, also writes the same in his book Umdat al-Qari – commentary of Sahih Bukhari.)[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Delage, Remy; Boivin, Michel (2015). Devotional Islam in Contemporary South Asia: Shrines, Journeys and Wanderers. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317380009.

- ^ Bilgrami, Fatima Zehra (2005). History of the Qadiri Order in India. Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli. p. 291.

- ^ Kafi South Asian folklore: an encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, by Peter J. Claus, Sarah Diamond, Margaret Ann Mills. Taylor & Francis, 2003. ISBN 0-415-93919-4. p. 317.

- ^ Kafi Crossing boundaries, by Geeti Sen. Orient Blackswan, 1998. ISBN 8125013415. p. 133.

- ^ Alkazi, Feisal (2014). Srinagar: An Architectural Legacy. New Delhi: Roli Books. ISBN 978-9351940517.

- ^ Acri, Andrea; Ghani, Kashshaf; Jha, Murari K.; Mukherjee, Sraman (2019). Imagining Asia(s): Networks, Actors, Sites. Singapore: ISEAS. ISBN 978-9814818858.

- ^ Currim, Mumtaz; Michell, George (1 September 2004). Dargahs, Abodes of the Saints. Mumbai: Marg Publications. ISBN 978-8185026657.

- ^ Khan, Motiur Rahman (2010). "Akbar and the Dargah of Ajmer". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 71. Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli: 226–235. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44147489.

- ^ "How Dargahs Unite People Of All Faiths". nayadaur.tv. 24 November 2020.

- ^ "Muslim Architecture". China.org. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- ^ "History of Dargah of Shah Ata". Asikolkata.in. ASI, Kolkata Circle. Retrieved 2017-08-22.

- ^ "Maqbara.com – Madurai Hazraths Maqbara". Archived from the original on May 17, 2008.

- ^ "Sheikh Nazım Al Haqqani Al Qubrusi An Naqshibandi". Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ "Building Mosques or Placing Lights on Graves" (PDF). 21 March 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ^ "Sahih Muslim 528a – The Book of Mosques and Places of Prayer – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)".

- ^ "Sahih al-Bukhari 3453, 3454 – Prophets – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)".

- ^ "Sunan an-Nasa'i 2048 – The Book of Funerals – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". sunnah.com.

- ^ "Sunan an-Nasa'i 2047 – The Book of Funerals – Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". sunnah.com.

- ^ a b Ondrej, Beranek; Tupek, Pavel (July 2009). Naghmeh, Sohrabi (ed.). From Visiting Graves to Their Destruction: The Question of Ziyara through the Eyes of Salafis (PDF). Crown Paper (Crown Center for Middle East Studies/Brandeis University). Brandeis University. Crown Center for Middle East Studies. p. 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2018.

Relying mainly on hadiths and the Qur'an, Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab's most famous work, The Book of God's Unicity (Kitab al-tawhid), describes a variety of shirk practices, such as occultism, the cult of the righteous (salih), intercession, oaths calling on other than God himself, sacrifices or invocational prayers to other than God, and asking other than Him for help. Important things about graves are remarked on in a chapter entitled "About the Condemnation of One Who Worships Allah at the Grave of a Righteous Man, and What if He Worships [the Dead] Himself."72 Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab starts by quoting a hadith: "Umm Salama told the messenger of Allah about a church she had seen in Abyssinia in which there were pictures. The Prophet said: 'Those people, when a righteous member of their community or a pious slave dies, they build a mosque over his grave and paint images thereon; they are for God wicked people.' They combine two kinds of fitna: the fitna of graves and the fitna of images." He then continues with another hadith: "When the messenger of Allah was close to death, he ... said: 'May Allah curse the Jews and Christians who make the graves of their prophets into places of worship; do not imitate them.'" From this hadith Ibn 'Abd al-Wahhab derives the prohibition of building places of worship over graves, because that would mean glorification of their inhabitants, which would amount to an act of worship to other than Allah.

- ^ "The Book of Prayer – Funerals – Sahih Muslim". Sunnah.com – Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم). Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ^ "Shrine – Oxford Islamic Studies Online". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved 2018-08-10.

Many modern Islamic reformers criticize visits to shrines as mere superstition and a deviation from true Islam.

- ^ "Sahih Muslim 530b - The Book of Mosques and Places of Prayer - Sunnah.com - Sayings and Teachings of Prophet Muhammad (صلى الله عليه و سلم)". sunnah.com. Retrieved 2024-01-30.

- ^ idarat al-ittabah al-Muniriya Qahira Egypt. Vol. 8. p. 134.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ernst, Carl W. (2022). Chapter 9: "The Spirituality of the Sufi Shrine". The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Islamic Spirituality. pp. 165–179. doi:10.1002/9781118533789.ch9.

External links

[edit] Media related to Dargahs at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dargahs at Wikimedia Commons

Dargah

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Historical Development

Early Islamic Precedents for Grave Veneration

The Prophet Muhammad initially prohibited visitation to graves during the early Medinan period to curb pre-Islamic practices of excessive mourning and potential idolatry, but subsequently permitted it as a reminder of mortality and the hereafter. A hadith narrated by Ibn Mas'ud states: "I had prohibited you from visiting graves, but now visit them, for they will remind you of the Hereafter," recorded in Sahih Muslim (no. 976).[6] This shift, occurring around 630–632 CE, established visitation (ziyarah) as a sanctioned practice focused on supplication for the deceased and personal reflection, rather than ritual excess.[7] The Prophet himself modeled grave visitation by regularly going to the burial site of the martyrs from the Battle of Uhud in March 625 CE, where he greeted them with salutations such as "Peace be upon you, O abode of a believing people" and invoked blessings upon them.[8] Historical reports indicate he performed this annually or whenever possible, emphasizing remembrance of sacrifice and divine reward, as transmitted through chains including Ibrahim ibn Muhammad.[9] Such acts by the Prophet provided direct precedents for honoring the graves of the righteous, including companions (sahabah), through verbal address and prayer, without erecting structures or seeking intercession.[10] Following the Prophet's death in 632 CE, companions began visiting his grave in the Prophet's Mosque in Medina, located in Aisha's chamber adjacent to his prayer niche, continuing the practice of greeting and supplicating at sacred sites associated with prophetic figures.[11] Early accounts, such as those from Imam Malik (d. 795 CE), recommend facing the grave during visitation while turning from the qibla to invoke blessings, reflecting a normative etiquette for sahaba tombs without elaboration into shrines.[12] These precedents—rooted in prophetic example and hadith—laid the groundwork for later expansions in grave-related devotion, though orthodox sources stress they were confined to simplicity and avoidance of worship-like veneration to prevent shirk (polytheism).[13] Archaeological and textual evidence from the formative period shows no widespread monumentalization, aligning with hadiths forbidding building mosques over graves.[14]Rise with Sufi Orders and Spread

The institutionalization of Sufi orders, known as tariqas or silsilas, from the 12th century onward facilitated the rise of dargahs as permanent shrines over the graves of spiritual masters, or pirs, shifting from transient ascetic practices to structured centers of devotion and transmission of esoteric knowledge. These orders created hierarchical chains of succession, where the legacy of deceased leaders was preserved through tomb veneration, drawing pilgrims seeking barakah (spiritual blessing) and fostering communal gatherings at khanqahs that often adjoined gravesites. This development built on earlier 8th-9th century Sufi mysticism but gained momentum as orders like the Chishti and Suhrawardiyya formalized rituals around saintly intercession, embedding dargahs within broader Islamic social structures.[15][16] In the Indian subcontinent, the Chishti order played a central role in this expansion, introduced by Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti (1142–1236 CE), who arrived in India around 1192 CE during the establishment of Muslim rule under the Ghurids and settled in Ajmer, Rajasthan. After his death in 1236 CE, his mausoleum became the Ajmer Sharif Dargah, one of the earliest and most influential Chishti shrines, attracting devotees from diverse backgrounds and exemplifying how dargahs served as hubs for sama' (spiritual music) and charity. Successors like Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki (d. 1235 CE) in Delhi further propagated the order, with their tombs evolving into pilgrimage sites that symbolized spiritual authority parallel to political power during the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526 CE).[17][18] Parallel growth occurred with the Suhrawardiyya order, founded by Shihab al-Din Umar al-Suhrawardi (d. 1234 CE) in Baghdad, which reached Punjab via Bahauddin Zakariya (1170–1262 CE), whose Multan shrine became a major center by the 13th century, emphasizing sobriety and adherence to Sharia alongside mysticism. The spread accelerated under sultanate patronage, with rulers granting waqf lands and madad-i-ma'ash stipends to sustain dargahs, enabling their proliferation across northern India, Bengal, and the Deccan by the 14th–15th centuries through orders like the Qadiriyya. This geographic expansion, numbering hundreds of notable dargahs by the Mughal era, supported Islam's dissemination among rural and non-Muslim populations via tolerant outreach, though reliant on state support for economic viability.[19][20]Evolution in Non-Arab Regions

In non-Arab regions, particularly South Asia and Central Asia, dargah veneration evolved from early individual Sufi migrations into institutionalized shrine complexes by the 14th century, adapting to local political patronage and cultural syncretism absent in core Arab Islamic practices. Sufi missionaries, often from Persianate backgrounds, arrived in India as early as the mid-12th century, with Khwaja Moinuddin Chishti settling in Ajmer around 1192 and establishing the Chishti order's presence until his death in 1236 CE.[21] However, systematic tomb-based devotion and architectural elaboration, such as transforming khanqahs into pilgrimage dargahs, gained momentum in the 14th century under Delhi Sultanate rulers, who provided endowments (waqfs) to legitimize their authority through saintly intercession.[22] This period marked a shift from unattached shaykhs to formalized silsilahs (lineages), evidenced by biographical texts like Fawa'id al-Fu'ad (late 13th-early 14th century) documenting Chishti networks and the construction of monumental tombs, such as that of Fariduddin Ganj-i Shakar in Pakpattan, completed circa 1330 CE.[22] In South Asia, dargahs incorporated indigenous elements like devotional music (qawwali) and inclusive rituals attracting Hindu and Muslim pilgrims, fostering conversions and social cohesion amid conquests, though orthodox critics viewed such adaptations as deviations from prophetic norms.[23] By the Mughal era (16th-19th centuries), imperial grants amplified dargah economies, with sites like Ajmer Sharif managing vast lands and annual urs festivals drawing thousands.[24] In Central Asia, parallel developments occurred under Timurid rulers, who elevated mazars (synonymous with dargahs) as symbols of spiritual and temporal power; for instance, Timur commissioned the mausoleum of Ahmad Yasavi in Turkestan between 1397 and 1405 CE, blending Persian architecture with regional nomadic influences to centralize piety.[25] These shrines evolved into waqf-supported hubs by the 15th century, as seen in Balkh's complexes managing economic resources until the 19th century, reflecting state-Sufi alliances that sustained veneration despite periodic Wahhabi-influenced purges.[26] Unlike Arab regions' restraint on grave markers, non-Arab dargahs emphasized perpetual saintly presence (haziri), integrating folk healing and astrology, which amplified their role in rural Islam but invited reformist condemnations as polytheistic accretions.[27]Architectural Features and Design

Core Elements of Dargah Structures

The central element of a dargah is the mazar, the tomb of the Sufi saint, typically located in an underground mortuary chamber known as the magbarah. This grave is marked above ground by a zarih, a latticed cenotaph enclosure, situated within a vaulted hall or chamber called the astanah or huzrah. [28] A prominent dome crowns the chamber housing the zarih, often a single large structure supported by thick brick walls measuring up to 0.9 meters in thickness, symbolizing spiritual elevation and serving as the architectural focal point. [28] [29] Surrounding the domed chamber, dargahs commonly feature four minarets at the corners for structural stability and visual emphasis, though some variations omit domes entirely in favor of flat roofs or additional minarets. [28] The overall layout follows a rectangular plan, enclosed by walls and often incorporating a spacious courtyard or garden for pilgrim gatherings, with adjacent facilities such as a mosque in larger complexes to support devotional activities. [28] [30] Intricate marble screens or jalis frequently surround the tomb area, allowing visibility while maintaining sanctity and providing ventilation, as seen in prominent examples where floral carvings and inscriptions enhance the spiritual ambiance. [29]Regional Variations and Influences

Dargahs exhibit regional variations arising from the integration of Persianate and Central Asian Islamic architectural principles with local vernacular traditions, resulting in diverse expressions of form, materials, and ornamentation across Muslim-majority regions.[31][32] In South Asia, these shrines typically feature core elements like domed mausoleums and courtyards but adapt to indigenous styles, such as the use of marble and jali screens in northern Indian examples influenced by Mughal patronage.[31] In northern India, dargahs like the Ajmer Sharif incorporate arcades, layered gateways, and hemispherical domes on square bases, blending Persian geometric forms with local motifs to symbolize spiritual gateways.[31][32] Southern Indian variants, such as the Nagore Dargah built in the 16th century, diverge by adopting Dravidian elements including tall minarets akin to Hindu temple gopurams, constructed with contributions from Hindu artisans and reflecting syncretic cultural exchanges.[33] In Pakistan, particularly Multan—known as the "City of Saints"—shrines emphasize elaborate blue-glazed tilework (kashi-kari) derived from Persian techniques, as seen in the 13th-century tomb of Bahauddin Zakariya, which uses enameled bricks for geometric patterns and Quranic inscriptions to evoke paradise gardens.[31][34] Central Asian and Persian dargahs, such as the 14th-century Ahmad Yasawi mausoleum in Turkestan, prioritize turquoise tiling, iwans, and charbagh layouts symbolizing cosmic order, with Iranian gunbads featuring vertical tower forms that accentuate domical roofs over enclosed tombs.[31][35] These contrasts highlight how Sufi architectural diffusion adapted to climatic, material, and cultural contexts while preserving underlying symmetries rooted in Islamic cosmology.[35]Rituals, Practices, and Cultural Role

Pilgrimage and Devotional Activities

Pilgrims visiting dargahs engage in ziyarat, a form of religious visitation aimed at honoring the deceased Sufi saint and seeking spiritual blessings or intercession.[36] This practice involves approaching the tomb (mazar) to recite prayers such as the Fatiha, offer floral tributes, incense, or a chadar (ceremonial sheet draped over the grave), and perform circumambulation or prostration in devotion.[37] Devotees often wash their hands and feet before entry as a ritual purification, reflecting embodied acts of humility and attunement to the shrine's sacred space.[38] Devotional activities frequently include communal dhikr (remembrance of God through rhythmic chanting) and sama sessions featuring qawwali, a form of Sufi devotional music that invokes divine presence and the saint's barakah (spiritual grace).[39] At major sites like the Ajmer Sharif Dargah, daily rituals encompass khidmat (service to the shrine), roshni (lighting of lamps at sunset), Quran recitation, and evening qawwali performances, which draw crowds for ecstatic worship.[40] These practices foster a sense of ethical and spiritual renewal, with pilgrims attributing physical, mental, or spiritual healing to the saint's enduring influence.[41] Langar, the provision of free communal meals, serves as a key devotional act, symbolizing charity and equality among visitors regardless of sect or background, and reinforces the dargah's role as a site of social and spiritual sustenance.[42] Votive offerings, such as tying threads or crawling to the shrine in extreme devotion, occur particularly among South Asian pilgrims seeking fulfillment of personal vows or resolution of afflictions.[43] Thousands visit prominent dargahs like those of Nizamuddin Auliya in Delhi or Muinuddin Chishti in Ajmer annually, blending individual piety with collective rituals that sustain Sufi traditions amid diverse regional influences.[37][44]Urs Ceremonies and Associated Customs

The Urs, derived from the Arabic term meaning "wedding," annually commemorates the death anniversary of a Sufi saint, interpreted as the soul's mystical union with God.[45] These observances at dargahs typically last from three to nine days, depending on the shrine's traditions, with the Ajmer Sharif Dargah marking the Urs of Moinuddin Chishti over six nights from the 1st to 6th of Rajab.[46][47] Central ceremonies include the hoisting of a ceremonial flag to inaugurate proceedings, followed by night-long qawwali performances and sama sessions featuring devotional poetry recitation to invoke spiritual ecstasy.[48] Devotees participate in collective prayers, Quran recitations, and fatiha offerings at the saint's tomb, seeking intercession and blessings.[49] Associated customs encompass presenting chadars—embroidered sheets draped over the grave—as symbols of devotion, alongside floral tributes and incense burning.[50] Langar, communal free meals, is distributed to attendees, reflecting the saint's emphasis on charity, while temporary bazaars form outside shrines, blending spiritual and local economic activities.[51] These practices, often inclusive of diverse religious participants, adapt to regional cultures but maintain core Sufi elements of remembrance and hospitality.[27]Socio-Economic Functions

Dargahs function as local economic engines through pilgrimage-driven tourism, sustaining ancillary industries such as hospitality, transportation, and retail in surrounding areas. The Ajmer Sharif Dargah, for example, anchors a vibrant bazaar economy where vendors sell religious artifacts, food, and services to millions of annual visitors, bolstering commerce in Rajasthan's Ajmer district.[52] Similarly, shrine complexes in Pakistan, like those of the Suhrawardiyya order, operate as trading hubs exchanging money, goods, and foodstuffs, integrating spiritual activity with market dynamics.[53] Donations and offerings collected at dargahs enable economic redistribution, funding shrine upkeep, welfare programs, and community infrastructure. At Ajmer Sharif, princely devotee contributions were valued at approximately Rs 60 crore annually as of 2014, with oversight mandated for transparent accounting to support charitable ends.[54] In rural South Asian contexts, such as Mitthan Kot in Pakistan's Upper Indus Basin, Sufi shrines stimulate micro-economies by drawing pilgrims who patronize local artisans and farmers, while endowment revenues (waqf) historically irrigated lands and built markets.[55] [56] Socially, dargahs promote cohesion via inclusive services like langar, communal kitchens distributing free meals to visitors regardless of class, faith, or origin, as practiced at shrines such as Baba Farid's darbar in Pakistan.[57] This provision extends to aid during crises, offering temporary shelter and resources that mitigate hardship for the economically vulnerable.[58] Beyond charity, these sites generate employment for khadims (caretakers), qawwali performers, and support staff, embedding dargahs in regional labor networks while serving as neutral venues for social interaction across divides.[2] In essence, dargahs blend devotional economies with welfare mechanisms, redistributing wealth through pilgrimage inflows to reinforce community resilience.[56]Geographical Distribution and Notable Examples

Prominence in South Asia

Dargahs occupy a central place in South Asian Muslim devotional life, particularly in India and Pakistan, where they function as major pilgrimage sites drawing millions of visitors annually from Muslim and non-Muslim communities alike for spiritual intercession, healing, and communal rituals.[59] The Ajmer Sharif Dargah in Rajasthan, India, enshrining the 13th-century Sufi saint Moinuddin Chishti of the Chishti order, exemplifies this prominence as one of the subcontinent's holiest sites, with its annual Urs festival commemorating the saint's death attracting vast crowds, including organized groups of Pakistani pilgrims numbering in the hundreds during peak events.[60][61] Similarly, the Nizamuddin Dargah in Delhi, dedicated to the 14th-century saint Nizamuddin Auliya, serves as a vibrant hub for qawwali performances and daily langar distributions, fostering interfaith participation and cultural continuity.[24] In Pakistan, dargahs underpin regional identities and mass devotion, with the Data Darbar in Lahore—tomb of the 11th-century scholar-saint Ali Hujwiri (Data Ganj Bakhsh)—recognized as a primary Sufi center hosting continuous pilgrim influxes and Thursday night gatherings.[4] The shrine of Bahauddin Zakariya in Multan, a key figure in the Suhrawardiyya order from the 13th century, further illustrates this, combining architectural grandeur with functions like free communal meals that support local economies and social welfare.[62] These sites historically facilitated Islam's expansion in South Asia from the 12th century onward through localized, inclusive practices that integrated pre-Islamic customs, enabling widespread appeal amid diverse populations.[38] Bangladesh features prominent examples like the Shah Jalal Dargah in Sylhet, burial place of the 14th-century saint credited with early Islamic propagation in Bengal, which continues to draw regional pilgrims for vows and festivities.[29] Across South Asia, dargahs sustain cultural roles beyond theology, including economic sustenance via associated markets and accommodations, while embodying syncretic traditions such as shared rituals that bridge Hindu-Muslim divides, though they occasionally face tensions from reformist critiques.[59][2] This enduring visibility underscores their embeddedness in everyday piety and regional heritage, with structures often evolving through Mughal-era patronage into multifaceted complexes.[24]Presence in Other Muslim Regions

In Turkey, Sufi shrines known as türbe serve functions analogous to dargahs, housing tombs of revered saints and attracting pilgrims for ziyarat despite historical bans on certain Sufi orders under secular reforms. For instance, the tomb of Yahya Efendi in Istanbul's Beşiktaş district, an Ottoman Sufi scholar who died in 1644, remains a site for devotional visits seeking intercession. Similarly, Istanbul features numerous such tombs of religious figures, including those of sheikhs from orders like the Halvetiyye, where rituals blend spiritual supplication with community gatherings, though official state policy since the 1920s has curtailed overt Sufi activities.[63][64] Central Asia hosts prominent mazar complexes, equivalents to dargahs, centered on Sufi saints' graves that draw regional pilgrims for blessings and annual commemorations. The Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmad Yasawi in Turkestan, Kazakhstan, built in the 14th century under Timurid patronage and designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2003, exemplifies this tradition; Yasawi (d. 1166), founder of the Yasawiyya order, is venerated through rituals including dhikr and offerings, reflecting pre-Soviet continuity despite Soviet-era suppressions. In Uzbekistan, the Baha-ud-Din Naqshband complex near Bukhara, tomb of the 14th-century Naqshbandi founder (d. 1389), functions as a khanqah-shrine hybrid, supporting pilgrimage economies and silent dhikr practices central to the order's emphasis on sobriety over ecstatic rituals.[65][66][25] In North Africa, zaouia institutions often incorporate Sufi saints' tombs, fostering localized veneration amid tariqa networks, though varying with regional orthodoxy. Morocco's Zawiya of Sidi Ahmed al-Tijani in Fez, housing the founder of the Tijaniyya order (d. 1815), serves as a global pilgrimage hub for the tariqa's millions of adherents, with rituals including collective salat al-fatih and vows of allegiance (bay'ah). Algeria's Tidjania Zaouia in Tamaxine centers on the tomb of a Tijaniyya figure, integrating educational and charitable roles typical of Maghrebi zaouias, which trace to medieval Almoravid and Almohad influences but faced 19th-century Wahhabi critiques.[67][68] Iran maintains khanqah-shrine ensembles for Sufi figures, blending Persian architectural grandeur with devotional practices akin to dargah urs, though overlaid with Shi'i imamzadehs. The Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardabili complex in Ardabil, a UNESCO site since 2010, enshrines the Safavid progenitor (d. 1334), founder of the Safaviyya order, and features octagonal tombs with iwans for ziyarat, historically pivotal in linking Sufism to dynastic legitimacy. The Shah Nematollah Vali Shrine in Mahan near Kerman, for the 14th-15th century Nimatullahi founder (d. 1431), hosts annual gatherings with qawwali-like sama' sessions, underscoring Sufism's enduring role despite post-revolutionary scrutiny.[69]Global Spread and Diaspora Instances

The dargah tradition has extended to diaspora communities in North America through the efforts of Sufi teachers who immigrated or were born there, establishing shrines that serve as focal points for spiritual practice among diverse followers. A prominent example is the mazar of M. R. Bawa Muhaiyaddeen in Coatesville, Pennsylvania, built over the grave of the Sri Lankan Sufi teacher Muhammad Raheem Bawa Muhaiyaddeen (d. 1986), who arrived in the United States in 1971 and founded the Bawa Muhaiyaddeen Fellowship in Philadelphia.[70] The structure, completed shortly after his death, functions as a pilgrimage site open to visitors daily, drawing adherents from Muslim immigrant communities and interfaith seekers for reflection and communal prayer, reflecting an adaptation of South Asian Sufi devotional culture to a Western context.[71] Another instance is the Dargah of Murshid Samuel Lewis at Lama Foundation in Questa, New Mexico, honoring Samuel Lewis (1896–1971), an American Sufi master and founder of the Dances of Universal Peace within the Chishtiyya-Inayati tradition.[72] Established posthumously at this interfaith spiritual retreat, the shrine accommodates pilgrims year-round when the foundation is accessible, emphasizing universalist Sufi elements that resonate with Western seekers beyond ethnic Muslim diaspora.[73] These North American examples, though fewer in number compared to South Asia, illustrate how dargah practices persist through transnational networks of Sufi orders, often integrating local customs while maintaining core rituals like visitation and meditation at the saint's tomb. In Europe, physical dargahs remain scarce, with South Asian Muslim diaspora communities—particularly Pakistani and Indian immigrants—primarily sustaining devotion via pilgrimages to ancestral shrines or through tariqa centers that emulate dargah functions without dedicated mausolea.[74]Theological and Juridical Perspectives

Sufi Arguments for Legitimacy

Sufi proponents maintain that dargahs serve as loci for tawassul (seeking nearness to Allah through intermediaries) and tabarruk (seeking blessings from the remnants of pious individuals), practices rooted in Quranic injunctions such as Surah Al-Ma'idah 5:35, which commands believers to "seek the means of nearness to Him."[75] This interpretation posits saints (awliya) as valid means due to their elevated spiritual status, with supplications directed ultimately to Allah rather than the deceased, thereby preserving tawhid (divine unity).[75] A foundational hadith evidence is the narration of Uthman ibn Hunayf, authenticated in Sunan al-Tirmidhi, wherein the Prophet Muhammad instructed a blind companion to seek intercession through him by saying, "O Allah, I ask You and turn to You through Your Prophet." Sufis extend this to post-mortem tawassul through prophets or righteous saints, citing companion practices like Bilal ibn Rabah's visitation to the Prophet's grave for similar supplication, as recorded in Al-Mu'jam al-Kabir by al-Tabarani and affirmed by al-Bayhaqi.[75] This form is endorsed by the majority of Sunni jurists across Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i, and Hanbali schools, who differentiate it from shirk by emphasizing that no independent power is ascribed to the intermediary.[75] Prominent Sufi scholars, such as Ahmad Raza Khan (d. 1921), a key figure in the Barelvi tradition, defended shrine visitation against reformist critiques by arguing it aligns with prophetic sunnah, including the encouragement to visit graves for remembrance of death (Sahih Muslim), while prohibiting excess like prostration to tombs. Khan asserted that circumnavigating or kissing graves of awliya constitutes veneration (ta'zim), not worship, provided the niyyah (intention) remains Allah-centric, and labeled outright prohibition as bid'ah (innovation) deviating from early Muslim praxis.[76] Such arguments invoke the metaphysical "presence" (hudur) of saints in the barzakh (intermediary realm), enabling their intercession (shafa'ah), as souls of the pious retain awareness and efficacy per hadiths in Sahih al-Bukhari and Muslim.[27] Critics' accusations of grave-worship are rebutted by Sufis through causal distinctions: barakah emanates from Allah via the saint's locus, akin to prophetic relics, without implying dualism; empirical continuity in traditions like the Chishti and Naqshbandi orders underscores its non-disruptive role in orthodox Islam.[76][75]Orthodox Sunni Objections Based on Tawhid

Orthodox Sunni scholars, particularly those following the Athari theological tradition, maintain that many dargah practices infringe upon tawhid al-uluhiyyah, the aspect of divine oneness requiring exclusive worship directed to Allah alone, by incorporating elements of shirk (associating partners with God). These objections stem from prophetic hadiths prohibiting the elevation of graves into sites of ritual veneration, such as the Prophet Muhammad's curse upon those who "take the graves of their prophets as places of worship," as recorded in Sahih al-Bukhari (1390) and Sahih Muslim (529). Constructing elaborate mausoleums or domes over graves, common in dargahs, is viewed as emulating the Jews and Christians in deifying the dead, thereby fostering idolatry that undermines the foundational Islamic prohibition against such structures to prevent their transformation into idols.[77] A core critique targets istighathah (seeking aid) and tawassul (intercession) through the deceased saints buried at dargahs, practices often involving supplications like "O saint, fulfill my need" or circumambulating graves while invoking the buried figure's power. Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 1328 CE), a pivotal Hanbali scholar whose works influence Salafi thought, classified such acts as impermissible innovations bordering on or constituting major shirk, arguing that directing pleas for help—whether for healing, protection, or worldly benefits—to anyone besides Allah equates to ascribing divine attributes of response and provision to creation. He permitted limited grave visitation solely for reflection on mortality and supplication to Allah alone at the site, but condemned journeying specifically to graves for intercession as a sinful bid'ah (innovation) that mimics pagan customs.[78] Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (d. 1792 CE), founder of the 18th-century reform movement in Najd, extended these arguments in Kitab al-Tawhid, dedicating chapters to how grave-centric rituals nullify tawhid by reviving pre-Islamic polytheism, where tribes venerated ancestors at tombs for barakah (blessings). He issued rulings deeming persistent tawassul through saints' graves as major shirk expelling one from Islam unless repented, prompting campaigns to demolish such structures to restore pure monotheism, as evidenced by alliances with the Al Saud family that razed hundreds of shrines between 1803 and 1806 CE in Arabia. Contemporary Salafi jurists, like Sulayman al-Al-Shaikh, reiterate that even non-worshipful veneration at dargahs—such as offerings, prostrations, or vows—violates tawhid by attributing rububiyyah (lordship) to the dead, contravening Quranic injunctions like "And do not call upon anyone besides Allah" (72:18).[79] These objections emphasize causal realism in worship: since the deceased lack awareness or agency post-death (Quran 35:22), relying on them for efficacy attributes occult powers to graves, eroding reliance on Allah's direct intervention. While acknowledging historical Sufi intent to commemorate piety, critics argue empirical outcomes—widespread talisman use, ecstatic rituals, and saint cults—demonstrate deviation into superstition, as documented in fatwas prohibiting dargah pilgrimage as a gateway to polytheism.[77]Views from Other Islamic Sects and Modern Reforms

Salafi and Wahhabi adherents, drawing from the theology of Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1792), reject the construction of dargahs and associated practices such as seeking intercession from saints as violations of tawhid (the oneness of God), classifying them as shirk (polytheism) or bid'ah (innovation). Influenced by earlier scholars like Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 1328), they argue that veneration at shrines diverts worship from Allah alone, prohibiting pilgrimages to tombs and rituals like qawwali or offerings, which they view as remnants of pre-Islamic or Hindu influences rather than authentic Sunnah.[80][81] The Ahl-i Hadith movement, emerging in 19th-century India under figures like Syed Nazeer Husain (d. 1902), similarly opposes saint veneration at dargahs, deeming it a breach of monotheism by elevating the dead to intermediaries, and advocates direct reliance on Quran and Hadith without taqlid (imitation of schools). They criticize shrine-building as impermissible, urging Muslims to avoid such sites to preserve doctrinal purity, though they permit grave visitation solely for reflection on mortality without supplication to the deceased.[82] Deobandi scholars, rooted in Hanafi jurisprudence but emphasizing reform, critique extravagant dargah practices—such as milad celebrations or fatiha offerings—as potential bid'ah bordering on shirk, distinguishing them from permissible tawassul (seeking means) through living scholars or prophetic supplication. While not endorsing destruction, they oppose Barelvi-style devotion that attributes supernatural powers to saints, arguing it dilutes core Islamic tenets; Deobandis identify as Sufis in ascetic discipline but reject folk accretions, as seen in fatwas from Darul Uloom Deoband founded in 1866.[83] Shia perspectives permit ziyarah (visitation) to graves for remembrance and supplication, as recommended in narrations from Imams like Ja'far al-Sadiq (d. 765), but prioritize shrines of the Twelve Imams and Ahl al-Bayt over Sunni Sufi dargahs, viewing the latter with caution if practices imply deification. Twelver Shia theology allows seeking proximity to God via the pure (ma'sum), yet Sufi saint cults are often seen as secondary or syncretic, with visitation justified for ethical reflection rather than guaranteed intercession.[84] Modern reformers like Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938) critiqued stagnant Sufi shrine-centric piety as promoting passivity and escapism, urging a reconstructed ijtihad (independent reasoning) to align mysticism with dynamic Quranic activism, rejecting dargah rituals that foster dependency on saints over self-reliant faith. Abul A'la Maududi (1903–1979), founder of Jamaat-e-Islami in 1941, advocated "true" Sufism confined to Sharia-compliant moral discipline, condemning shrine veneration as degenerative deviations from early ascetic models, emphasizing socio-political engagement over tomb pilgrimages to combat colonial-era cultural erosion.[85]Controversies, Criticisms, and Incidents

Historical and Contemporary Oppositions

Opposition to dargahs within Islamic traditions has roots in early prophetic injunctions against treating graves as sites of worship or supplication, as recorded in hadiths where Muhammad warned against emulating predecessors who venerated the tombs of prophets and righteous figures. Such practices were viewed as deviations risking shirk, or association with God, prompting calls for simplicity in burial and visitation.[87] In medieval Islam, Hanbali scholar Ibn Taymiyyah (1263–1328) articulated systematic critiques of certain Sufi customs, including the construction of elaborate shrines and rituals at graves, which he argued fostered innovation (bid'ah) and potential idolatry contrary to tawhid's strict monotheism.[88] He distinguished between ascetic Sufis aligned with orthodoxy and those engaging in excessive veneration, such as circumambulating tombs or seeking intercession through the deceased, practices he deemed unsubstantiated by core texts and liable to corrupt pure worship.[89] These views influenced later reformist strands, emphasizing scriptural fidelity over saintly mediation. Contemporary oppositions, often framed through Salafi and Wahhabi lenses, manifest in physical demolitions and doctrinal condemnations. In Saudi Arabia, Wahhabi authorities since the 18th-century alliance with the Al Saud family have razed numerous shrines, including over 300 historical sites in Mecca and Medina by the early 21st century, justifying actions as eradicating polytheistic remnants to uphold tawhid.[90] Notable instances include the 1806 destruction of domes in Medina's Baqi cemetery and later expansions bulldozing Prophet's companions' tombs, driven by fears of grave worship.[91] In South Asia, Deobandi scholars, emerging from the 19th-century Darul Uloom Deoband seminary, reject dargah embellishments and associated rituals like prostration or offerings as impermissible innovations, permitting only simple grave visits for supplication to God without saintly intercession.[92] This stance fuels tensions with Barelvi proponents of shrine veneration, evident in Pakistan and India where Deobandi-influenced groups decry dargahs as sites of shirk, occasionally leading to protests or calls for reform.[93] Groups like the Taliban in Afghanistan have echoed these positions by targeting shrines deemed idolatrous, destroying Sufi mausoleums alongside non-Islamic artifacts since the 1990s to enforce perceived scriptural purity.[94]Instances of Destruction and Violence

In Pakistan, Sufi shrines have faced repeated terrorist attacks by Islamist militants opposed to practices they deem unorthodox. The Data Darbar shrine in Lahore, dedicated to Ali Hujwiri, was struck by two suicide bombings on July 1, 2010, killing 41 people and injuring more than 170 during a period of high pilgrimage attendance.[95] A suicide bombing near the same shrine on May 8, 2019, killed at least 10 people, including security personnel, and wounded 20 others, occurring during Ramadan when crowds were dense.[96] Similarly, on February 16, 2017, the Islamic State conducted a suicide bombing at the Lal Shahbaz Qalandar shrine in Sindh province, killing over 80 devotees and injuring hundreds, explicitly targeting Sufi rituals as idolatrous.[97] In Syria and Iraq, the Islamic State systematically demolished Sufi shrines as part of its campaign against perceived deviations from strict monotheism. In June 2015, ISIL forces used explosives to destroy several ancient shrines and tombs near Palmyra, including those associated with Sufi figures, following their capture of the area and amid broader assaults on pre-Islamic and heterodox Islamic sites.[98] Hardline groups like Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIL escalated attacks on Sufi shrines after their 2013 split, bulldozing or bombing structures in rebel-held territories to enforce Salafi interpretations of tawhid, with dozens of sites razed between 2013 and 2015. Following political upheaval in Bangladesh starting August 2024, over 100 Sufi shrines and dargahs were vandalized, looted, burned, or partially demolished by mobs, often under pretexts of blasphemy or opposition to saint veneration.[99] Police reports documented at least 44 violent incidents against 40 shrines by January 2025, amid broader sectarian tensions targeting moderate Islamic practices.[100] These acts, linked to far-right Islamist factions, involved physical destruction such as torching mausoleums and desecrating graves, exacerbating communal divides in a country with deep Sufi heritage.[101]Responses and Defenses in Practice

In response to terrorist attacks on Sufi shrines in Pakistan, such as the July 1, 2010, suicide bombings at Data Darbar in Lahore that killed 42 people and the May 8, 2019, explosion nearby that claimed 10 lives including police officers, authorities have deployed enhanced security measures including barricades, bomb disposal squads, and routine patrols around major dargahs.[102] These steps, often involving provincial police and counterterrorism units, aim to deter further assaults by groups like Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan, which have targeted shrines for their perceived promotion of unorthodox practices.[96] Despite such incidents, annual urs festivals and pilgrimages persist, with millions attending events like those at Data Darbar, demonstrating communal resilience as a de facto defense against disruption.[103] In India, legal mechanisms have provided defenses against demolitions motivated by encroachment claims or ideological opposition, with courts enforcing due process and historical protections. For instance, on June 29, 2025, the Gujarat High Court issued contempt notices to municipal officials for razing a 300-year-old dargah in Junagadh despite existing safeguards, underscoring judicial oversight to prevent arbitrary actions.[104] The Supreme Court has similarly ruled that while illegal structures must be removed regardless of religious affiliation—applying to both temples and dargahs—demolitions require notice and cannot serve as punitive tools without evidence, as affirmed in October 2024 guidelines on bulldozer actions.[105] Sufi organizations, such as the All India Sufi Shrines Conference, have supported Waqf Act amendments in 2024 to curb mismanagement while advocating for shrines as cultural heritage sites integral to pluralism, countering narratives of shirk from Salafi critics.[106] Practically, Sufi communities maintain defenses through cultural continuity and counter-narratives, with qawwali performances and shrine administrations rejecting Wahhabi-influenced clerics to preserve orthodox Sufi governance.[107] In regions like South Asia, these practices affirm tawhid-compatible veneration by emphasizing the saints' role as intermediaries for spiritual guidance rather than idolatry, sustained amid threats as a form of ideological resistance.[108] Such responses, including protests against selective targeting, highlight shrines' role in fostering interfaith harmony against extremist ideologies.[109]References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/348594876_A_Critical_Appreciation_of_Abu_al-A%27la_al-Mawdudi%27s_Reading_of_Sufism