Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Later Zhou

View on WikipediaZhou, known as the Later Zhou (/dʒoʊ/;[1] simplified Chinese: 后周; traditional Chinese: 後周; pinyin: Hòu Zhōu) in historiography, was a short-lived Chinese imperial dynasty and the last of the Five Dynasties that controlled most of northern China during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Founded by Guo Wei (Emperor Taizu), it was preceded by the Later Han dynasty and succeeded by the Northern Song dynasty.

Key Information

Founding of the dynasty

[edit]Guo Wei, a Han Chinese, served as the Assistant Military Commissioner at the court of the Later Han, a regime ruled by Shatuo Turks. Liu Chengyou came to the throne of the Later Han in 948 after the death of the founding emperor, Gaozu. Guo Wei led a successful coup against the teenage emperor and then declared himself emperor of the new Later Zhou on New Year's Day in 951.

Rule of Guo Wei

[edit]Guo Wei, posthumously known as Emperor Taizu of Later Zhou, was the first Han Chinese ruler of northern China since 923. He is regarded as an able leader who attempted reforms designed to alleviate burdens faced by the peasantry. His rule was vigorous and well-organized. However, it was also a short reign. His death from illness in 954 ended his three-year reign. His adoptive son Chai Rong (also named Guo Rong) would succeed his reign.

Rule of Guo Rong

[edit]Guo Rong, posthumously known as Emperor Shizong of Later Zhou, was the adoptive son of Guo Wei. Born Chai Rong, he was the son of his wife's elder brother. He ascended the throne on the death of his adoptive father in 954. His reign was also effective and was able to make some inroads in the south with victories against the Southern Tang in 956. However, efforts in the north to dislodge the Northern Han, while initially promising, were ineffective. He died an untimely death in 959 from an illness while on campaign.

Fall of the Later Zhou

[edit]Guo Rong was succeeded by his seven-year-old son upon his death. Soon thereafter, Zhao Kuangyin usurped the throne and declared himself emperor of the Great Song dynasty, a dynasty that would eventually reunite China, bringing all of the southern states into its control as well as the Northern Han by 979.

Rulers

[edit]| Temple names (Miao Hao 廟號) | Posthumous names (Shi Hao 諡號) | Personal names | Period of reigns | Era names (Nian Hao 年號) and their according range of years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tàizŭ (太祖) | Too tedious thus not used when referring to this sovereign | 郭威 Guō Weī | 951–954 | Guǎngshun (廣順) 951–954 Xiǎndé (顯德) 954 |

| Shìzōng (世宗) | Too tedious thus not used when referring to this sovereign | 柴榮 Chái Róng | 954–959 | Xiǎndé (顯德) 954–959 |

| Did not exist | 恭帝 Gōngdì | 柴宗訓 Chái Zōngxùn | 959–960 | Xiǎndé (顯德) 959–960 |

Later Zhou emperors' family tree

[edit]| Later Zhou emperors family tree | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Currency

[edit]

The only series of cash coins attributed to the Later Zhou period are the Zhouyuan Tongbao (simplified Chinese: 周元通宝; traditional Chinese: 周元通寶; pinyin: zhōuyuán tōng bǎo) coins which were issued by Emperor Shizong from the year 955 (Xiande 2).[2][3] Emperor Shizong is sometimes said to have cast cash coins with the inscription Guangshun Yuanbao (simplified Chinese: 广顺元宝; traditional Chinese: 廣順元寶; pinyin: guǎng shùn yuánbǎo) during his Guangshun period title (951–953), however no authentic cash coins with this inscription are known to exist.

The pattern of the Zhouyuan Tongbao is based on that of the Kaiyuan Tongbao cash coins. They were cast from melted-down bronze statues from 3,336 Buddhist temples and mandated that the citizens of Later Zhou should turn in to the government all of their bronze utensils with the notable exception of bronze mirrors, Shizong also ordered a fleet of junks to go to Korea to trade Chinese silk for copper which would be used to manufacture cash coins. When reproached for this, the Emperor uttered a cryptic remark to the effect that the Buddha would not mind this sacrifice. It is said that the Emperor himself supervised the casting at the many large furnaces at the back of the palace. The coins are assigned amuletic properties and "magical powers" because they were made from Buddhist statues and are said to particularly effective in midwifery – hence the many later-made imitations which are considered to be a form of Chinese charms and amulets. Among these assigned powers it is said that Zhouyuan Tongbao cash coins could cure malaria and help women going through a difficult labour. The Chinese numismatic charms based on the Zhouyuan Tongbao often depict a Chinese dragon and fenghuang as a pair on their reverse symbolising either a harmonious marriage or the Emperor and Empress, other images on Zhouyuan Tongbao charms and amulets include depictions of Gautama Buddha, the animals of the Chinese zodiac, and other auspicious objects.[4][5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Zhou". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ Hartill, David (September 22, 2005). Cast Chinese Coins. Trafford, United Kingdom: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1412054669. Pages 113–114.

- ^ Numis' Numismatic Encyclopedia. A reference list of 5000 years of Chinese coinage. (Numista) Written on December 9, 2012 • Last edit: June 13, 2013. Retrieved: 13 September 2018.

- ^ "Chinese coins – 中國錢幣". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 16 November 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ "Chinese Cast Coins – POSTERIOR ZHOU DYNASTY – AD 951–960 – Emperor SHIH TSUNG – AD 954-959". By Robert Kokotailo (Calgary Coin & Antique Gallery – Chinese Cast Coins). 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

Sources

[edit]- Mote, F. W. (1999). Imperial China (900–1800). Harvard University Press. pp. 13, 14.

- "5 DYNASTIES & 10 STATES". Retrieved 2006-10-08.

Later Zhou

View on GrokipediaHistorical Context and Founding

The Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms Period

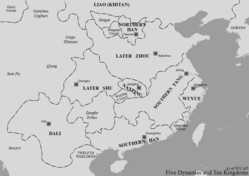

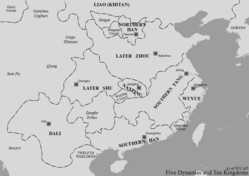

The collapse of the Tang dynasty in 907, precipitated by warlord Zhu Wen's usurpation, ushered in the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907–960), a time of acute political division and instability across China. In the north, where the imperial capitals of Kaifeng and Luoyang lay, power shifted rapidly among five ephemeral dynasties founded by military strongmen: Later Liang (907–923), Later Tang (923–936), Later Jin (936–947), and Later Han (947–951).[6][7] These regimes typically endured less than a decade each, sustained by fragile alliances of soldiers and eunuchs but undermined by incessant coups, betrayals, and successions favoring adopted heirs over biological kin to avert familial strife.[7][8] Southern China, insulated by natural barriers like the Qinling Mountains, fragmented into ten kingdoms that proved more enduring and economically viable than their northern counterparts. Major entities included Wu (902–937), Southern Tang (937–975), Wuyue (907–978), Min (909–945), Chu (907–951), Southern Han (917–971), Former Shu (907–925), Later Shu (934–963), and Nanping (924–960), with Northern Han (951–979) as a northern outlier.[6][9] These states fostered relative stability through lighter warfare, advanced irrigation, and commerce in tea, silk, and sericulture, contrasting the north's devastation from conscription and heavy taxation.[9][8] Underlying this fragmentation were structural weaknesses inherited from late Tang rule, including the empowerment of regional military governors (jiedushi) following the An Lushan Rebellion (755–763), which killed over one million and shattered central fiscal and military control.[10] Later upheavals, such as the Huang Chao Rebellion (874–884) that sacked Chang'an and Luoyang, compounded by court eunuch factions and abandoned equal-field land systems leading to inequality and revenue shortfalls, entrenched warlord autonomy.[10][6] External pressures mounted with the Khitan Liao dynasty's founding in 916, which capitalized on dynastic turmoil through opportunistic alliances—like aiding Later Jin's founder—and invasions that seized northern territories, including the capital in 946–947, further eroding cohesion.[8] Such pervasive disorder, blending internal strife with exogenous incursions, eroded legitimate authority and primed the north for consolidation under emergent leaders.[8]Rise and Establishment under Guo Wei

Guo Wei (904–954), born into humble origins in Yaoshan County (modern-day Longyao County, Hebei), began his career as a low-ranking soldier amid the chaos following the Tang dynasty's collapse. Orphaned early, he enlisted in regional armies, earning promotion through demonstrated loyalty and martial skill during service under warlords like Li Keyong and subsequent regimes. By the establishment of Later Han in 947 under Liu Zhiyuan—a Shatuo Turkic general whom Guo had supported—Wei had risen to become assistant military commissioner, a position reflecting his trusted status despite his Han Chinese ethnicity and lack of elite pedigree. His steadfastness during earlier rebellions, including suppressing uprisings against Liu Zhiyuan, solidified his influence over key troops in the northern heartland.[11] In early 951, tensions escalated under the teenage Later Han emperor Liu Chengyou, whose erratic rule and suspicions of disloyalty fueled military unrest, exacerbated by fiscal strains from aggressive tax demands on soldiers and locals to fund court extravagance. While Guo Wei was campaigning with his forces away from the capital, Liu ordered the execution of Guo's extended family on grounds of suspected treason, igniting a mutiny among the outraged troops who hailed Guo as their savior and compelled him to rebel. The army swiftly advanced on Bianjing (modern Kaifeng), overcoming minimal resistance as palace guards collapsed amid the chaos; Liu Chengyou perished in the sack of the city, marking the effective end of Later Han rule.[12][13] On February 13, 951, Guo Wei reluctantly accepted acclamation as emperor from his soldiers and officials in Bianjing, formally proclaiming the Later Zhou dynasty and adopting the temple name Taizu posthumously. This establishment secured control over the core northern territories along the Yellow River plain, encompassing Henan, Shanxi, and parts of Shaanxi, though peripheral regions like Northern Han remained defiant. Initial consolidation involved purging Han loyalists while integrating compliant elites, leveraging Guo's reputation for fairness to stabilize the army and administration without immediate expansionist ventures.[3][1]Reigns of the Emperors

Emperor Taizu (Guo Wei, 951–954)

Guo Wei ascended the throne on December 16, 951, following the abdication of Later Han's Emperor Ying (Liu Chengyou), establishing the Later Zhou dynasty after his troops mutinied in response to the executions of high officials and marched on Kaifeng.[14] Born in 904 to a family of modest means in Taiyuan, Shanxi, Guo had risen through military service in the Later Jin and Later Han, earning trust for his competence and loyalty amid the era's frequent usurpations.[15] His immediate priorities centered on consolidating control, as regional warlords and pretenders posed threats to the nascent regime; several local commanders submitted or abdicated in favor of Zhou authority within months of his proclamation, averting immediate fragmentation.[16] To stabilize the military, Guo rewarded key supporters with promotions, land allotments, and stipends, fostering loyalty among roughly 100,000 troops under his direct command while disbanding unreliable units to curb potential revolts.[15] Administratively, he prioritized merit-based appointments, elevating scholar-officials like Wang Pu to chancellor in 952, who advised on fiscal prudence, diverging from prior dynasties' favoritism toward aristocratic kin.[17] Efforts to address Later Han's fiscal exhaustion included edicts forgiving peasant debts, lightening corvée labor, and curbing official extortion, which historical accounts attribute to restoring some agricultural output in the core Henan region despite ongoing banditry. These measures aimed at causal recovery—linking reduced burdens to increased tax yields—though their brevity limited measurable impact, as evidenced by persistent grain shortages noted in contemporary records. Lacking biological heirs, Guo adopted Chai Rong, the son of his elder sister and a capable commander, in 953, designating him crown prince to ensure smooth transition amid his own health decline.[18] In February 954, during preparations near the northern frontier, Guo succumbed to illness on the 22nd, aged 50; autopsy reports in dynastic annals described acute dysentery exacerbated by fatigue.[6] His three-year tenure, though unmarred by major defeats, emphasized pragmatic governance over expansion, setting precedents for meritocracy and fiscal restraint that successors built upon, per analyses of primary compilations like the Jiu Wudai Shi.[16]Emperor Shizong (Chai Rong, 954–959)

Chai Rong ascended the throne as Emperor Shizong of Later Zhou on 22 February 954, immediately following the death of his adoptive father, Emperor Taizu Guo Wei.[19] As the son of Guo Wei's sister-in-law and a trusted military figure under the previous emperor, Chai Rong had already demonstrated administrative competence and loyalty during the dynasty's founding phase. His reign, lasting until his untimely death in 959 from illness during a campaign, is regarded as the apogee of Later Zhou's short existence, marked by proactive governance aimed at stabilizing and strengthening the state amid the fragmentation of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. Shizong pursued internal reforms to enhance administrative efficiency, emphasizing the selection of capable administrators over rigid adherence to pedigree, which contributed to a relative increase in civilian officials during Later Zhou compared to prior military-dominated regimes.[20] He cracked down on bureaucratic inefficiencies and corruption through direct oversight, personally reviewing officials' performance and demoting or punishing those deemed incompetent or venal, thereby instilling discipline in the central apparatus at Kaifeng. These measures streamlined decision-making and reduced factional interference, allowing for more responsive policy implementation. On the fiscal front, Shizong implemented tax relief for peasants to stimulate agricultural recovery, lightening burdens that had exacerbated unrest in preceding dynasties, while redirecting resources toward military readiness for broader unification efforts. A key revenue initiative involved restricting Buddhism for economic imperatives, including the demolition of excess temples and the smelting of bronze statues into coins, which augmented state coffers without solely relying on peasant levies.[21] This policy, enacted around 955, yielded substantial metallic reserves for minting currency like the Zhou Yuan Tong Bao, funding administrative and defensive priorities while curbing the economic drain of monastic landholdings and exemptions. Shizong's strategic focus on fiscal prudence and merit-based governance laid preparatory foundations for territorial consolidation, though his early death curtailed full realization.Emperor Renzong (Chai Zongxun, 959–960)

Chai Zongxun ascended the throne as Emperor Renzong on July 27, 959, succeeding his father, Emperor Shizong Chai Rong, who died of illness at age 38 while preparing for a military expedition. Born September 14, 953, the new emperor was six years old by Gregorian reckoning—or seven sui by traditional Chinese age-counting—and his nominal rule extended only until February 960.[22][3] Due to the emperor's extreme youth, effective governance fell to a regency comprising the Empress Dowager Fu (Shizong's widow) and senior civil officials, including Chancellor Wang Pu, who maintained administrative continuity by upholding Shizong's fiscal reforms and military mobilizations against northern Liao threats. No major policy innovations occurred, as the court focused on stability amid ongoing border tensions and resource strains from prior campaigns; however, the lack of decisive leadership amplified internal power vacuums.[23] The regency's weaknesses became evident in the growing autonomy of military commanders, particularly Zhao Kuangyin, who as head of the palace guards wielded substantial influence over loyal troops and logistics, foreshadowing the dynasty's rapid collapse without ascribing intent to usurpation. This period underscored Later Zhou's reliance on charismatic prior rulers, rendering the child sovereign a symbolic figurehead vulnerable to factional dynamics.[24][3]Governance and Reforms

Administrative and Fiscal Reforms

Under Emperor Taizu (Guo Wei, r. 951–954), initial administrative reforms focused on centralization and alleviating peasant hardships to prevent unrest, including reductions in tax burdens and elimination of excessive corvée labor demands. These measures aimed to restore agricultural stability in war-torn northern China by curbing the fiscal excesses inherited from prior dynasties.[2] Emperor Shizong (Chai Rong, r. 954–959) advanced these efforts through further centralizing reforms, such as streamlining redundant bureaucratic offices and enhancing merit-based selection of officials via provincial examinations, which diminished hereditary aristocratic influence in appointments. He also reformed local governance by tightening central oversight of prefectural administrations, prohibiting officials from engaging in private trade or accumulating land in their jurisdictions to combat corruption and ensure equitable enforcement.[25] Fiscal policies under Shizong emphasized tax equalization across regions, with adjustments to land assessments that redistributed burdens more fairly while increasing state revenues through improved collection mechanisms and reductions in exemptions for elites. These changes, including incentives for land reclamation and limits on aristocratic estates, boosted agricultural output in core territories, as evidenced by historical records showing fewer peasant uprisings—averaging eight fewer incidents annually during the reform period compared to preceding dynasties.[26][2] The reforms' success in fostering efficiency is corroborated by the dynasty's ability to sustain military campaigns without fiscal collapse, though their brevity limited long-term verification.[25]Military Organization and Structure

The Later Zhou military was structured around a professional standing army, primarily composed of cavalry units inherited from Shatuo Turkic traditions and supplemented by Han Chinese infantry recruits, with an estimated core force of around 100,000 to 150,000 troops maintained through salaried service rather than conscription.[14] This composition emphasized mobility and discipline, drawing from diverse ethnic groups to bolster numbers while prioritizing loyalty through regular pay funded by fiscal reforms that alleviated peasant tax burdens, thereby enabling broader recruitment from rural populations. Training focused on coordinated cavalry-infantry tactics, with incentives such as land grants for veteran soldiers to foster retention and reduce desertions common in prior dynasties. Under Emperor Shizong (Chai Rong, r. 954–959), significant reforms centralized command authority, curtailing the autonomy of regional warlords by prohibiting private armies and integrating conquered forces directly into imperial units under trusted palace commanders.[14] [27] These measures included reorganizing the imperial guards into a more directly controlled elite force, personally led by the emperor in campaigns to ensure adherence to central directives, which diminished mutinies by aligning officer incentives with the throne but heightened reliance on capable generals whose personal ambitions later facilitated the 960 coup.[28] Provincial garrisons were subordinated to capital oversight, with rotations and audits to prevent entrenchment, reflecting a causal shift toward stability through hierarchical control rather than feudal delegation. This structure proved effective in suppressing internal dissent but sowed seeds for dynastic transition by empowering figures like Zhao Kuangyin with outsized influence over mobile field armies.Military Campaigns and Expansion

Northern Expeditions against Liao and Kingdoms

Under Emperor Shizong (Chai Rong), the Later Zhou launched offensive campaigns northward to challenge Liao dominance over the Sixteen Prefectures of Yan and Yun, regions ceded by the Later Jin in 938 that provided Liao with a strategic buffer and economic base in northern Hebei and Shanxi.[2] These expeditions targeted Liao-held prefectures and aimed to sever their support for the Northern Han kingdom, a persistent rival in Shanxi allied with the Khitans.[2] While initial successes yielded territorial gains, full reconquest eluded Later Zhou due to logistical limits and Shizong's untimely death. In spring 959, Shizong personally led approximately 100,000 troops in a major expedition, advancing through key passes to assault Liao positions near Youzhou (modern Beijing).[29] The campaign rapidly secured three strategic prefectures—Jinzhou (modern Chengde area), Lulong, and others in eastern Hebei—along with associated passes, disrupting Liao's frontier defenses and forcing Khitan withdrawal from exposed garrisons.[30] These victories temporarily extended Later Zhou control over border counties, yielding grain taxes and cavalry recruits from the reclaimed Han populations, though garrisons strained supply lines amid summer rains.[2] Concurrent operations pressured Northern Han, whose ruler Liu Chengyou sought Liao aid against Zhou incursions into Taiyuan's outskirts. Shizong's forces inflicted defeats on Han-Liao combined armies in skirmishes, capturing border forts and compelling Northern Han to divert resources southward, thereby isolating it from full Khitan reinforcement.[2] A planned deeper thrust toward Youzhou in mid-959 was aborted when Shizong contracted dysentery during the advance, dying on July 27 at the age of 39; command devolved to subordinates, who consolidated holdings but abandoned further offensives amid succession uncertainties.[29] The expeditions weakened Liao's regional hegemony by reclaiming fertile plains vital for their southern campaigns, while exposing Northern Han's vulnerabilities—paving the path for Song dynasty forces to exploit these fractures post-960.[2] Retained gains included fortified outposts that bolstered Zhou defenses, though Liao counter-raids reclaimed peripheral areas by 960, underscoring the campaigns' incomplete strategic resolution.[30]Southern and Internal Consolidations

During the reign of Emperor Shizong (Chai Rong, r. 954–959), Later Zhou forces launched targeted campaigns to secure southern frontiers against the Southern Tang kingdom, capturing key territories in the Huai River basin. In 955, Shizong personally commanded an expedition that overran Chuzhou and surrounding areas, forcing Southern Tang to surrender 14 prefectures including Shouchun, thereby establishing direct control over the Huainan circuit and disrupting Southern Tang's defensive lines.[31] These gains temporarily expanded Later Zhou's effective territory southward by approximately 200,000 square kilometers, enhancing fiscal revenues from rice taxes in the fertile Huai region.[14] Subsequent offensives in 956–958 further pressured Southern Tang, with Shizong's armies seizing additional strongholds like Taozhou and Huangzhou after decisive battles, compelling Southern Tang's ruler Li Jing to renounce imperial pretensions, pay annual tribute of 100,000 bolts of silk, and acknowledge Later Zhou suzerainty.[32] Diplomatic stabilization followed, as Southern Tang envoys formalized border demarcations and tribute protocols to avert total conquest, allowing Later Zhou to redirect resources northward without immediate southern threats.[33] Parallel efforts against Later Shu in the southwest yielded four provinces by 957, including strategic riverine access points that bolstered supply lines for eastern operations.[14] Internally, Shizong prioritized consolidation by suppressing nascent separatist movements and rectifying local military commands in central China. Upon ascending the throne in 954, he disbanded unreliable provincial garrisons, reallocating 10,000 elite troops to a centralized palace army to curb warlord autonomy and prevent uprisings akin to those under prior regimes, such as the unsubmissive forces in Xuzhou and Guanzhou.[2] These measures, enforced through targeted purges and loyalty oaths from regional commanders, quelled minor rebellions in Henan and Shanxi by 955, restoring tax collection efficiency and reducing administrative fragmentation.[27] While these actions yielded short-term stability, the rapid mobilization for southern thrusts—drawing over 100,000 troops annually—imposed logistical strains, as evidenced by supply shortages reported in campaign annals.[34]Economy and Society

Economic Recovery and Policies

Under Emperor Taizu (Guo Wei, r. 951–954), early policies focused on easing the fiscal pressures on peasants ravaged by prior conflicts, including reductions in tax rates and penalties to promote rural stability and basic agricultural resumption.[35] These measures addressed the depleted tax base inherited from the Later Han dynasty, prioritizing peasant relief over aggressive revenue extraction.[2] Emperor Shizong (Chai Rong, r. 954–959) advanced economic revitalization through targeted agricultural initiatives. He oversaw water conservancy projects, notably enhancing irrigation systems around Kaifeng to bolster crop yields and support post-war resettlement.[36] In 955, Shizong enacted a suppression of Buddhism, demolishing 3,336 temples and monasteries, which enabled the confiscation and redistribution of vast tax-exempt ecclesiastical lands to lay farmers, thereby augmenting cultivable acreage and state taxable revenue while curtailing non-productive monastic holdings.[37] These reforms, implemented amid ongoing military consolidations, fostered incremental recovery in agrarian output and fiscal capacity during the dynasty's brief tenure.[38]Currency and Trade Systems

Emperor Shizong (Chai Rong) addressed a copper shortage in 955 CE by ordering the melting of bronze from Buddhist statues and temple artifacts to mint new cash coins inscribed Zhouyuan Tongbao (周元通寶).[39] [40] These coins, produced during the Xiande era (954–959 CE), featured high manufacturing quality and became the primary currency of the Later Zhou dynasty.[41] The reform aimed to standardize monetary circulation amid fragmented post-Tang economies, replacing irregular prior issuances with uniform 1-cash denominations.[42] The increased minting output from repurposed metals expanded the money supply, correlating with reported improvements in currency quality and economic activity.[3] Historical records indicate that this bolstered fiscal revenues, as the enhanced circulation supported administrative functions and military funding without immediate inflationary pressures.[39] Efforts to curb counterfeiting were implicit in the coins' superior craftsmanship, though persistent shortages limited long-term stability.[41] Standardized Zhouyuan Tongbao coins facilitated trade integration across Later Zhou territories, enabling smoother exchanges in markets previously divided by diverse local currencies from rival kingdoms.[3] Military consolidations secured northern trade routes, promoting commerce in staples like grain and silk between central plains regions and annexed areas, with minting surges aligning to revenue growth from heightened inter-kingdom transactions.[39] No widespread paper money precursors emerged, as reliance remained on copper-based systems inherited from Tang precedents.[40]Fall of the Dynasty

Internal Instability and Succession Crisis

The death of Emperor Shizong Chai Rong on July 27, 959, precipitated a succession crisis in the Later Zhou dynasty, as his seven-year-old son, Chai Zongxun, ascended the throne as Emperor Gong without the capacity to assert independent authority.[2] This transition exposed the fragility of a regime dependent on a single capable ruler, with institutional mechanisms insufficient to ensure continuity amid the dynasty's brief existence and reliance on adoptive lineages originating from Guo Wei.[27] Governance devolved to a regency dominated by senior civil officials, including Chancellor Fan Zhi and military advisor Wang Pu, who consulted on critical decisions but lacked unified control over the powerful generals elevated during Shizong's reforms.[24] The child's nominal rule failed to inspire loyalty from military commanders, who commanded elite troops hardened by recent campaigns, fostering latent tensions between bureaucratic administrators prioritizing fiscal restraint and martial elites seeking greater autonomy and rewards.[2] Compounding these divisions, the dynasty's aggressive northern expeditions against the Liao and internal consolidations had imposed severe fiscal pressures, leaving the treasury depleted and unable to fully compensate soldiers, which bred discontent and eroded discipline within the ranks. Although Shizong's bronze procurement drives aimed to mint currency for debt relief, persistent arrears underscored the unsustainability of sustained warfare without deeper administrative reforms, amplifying vulnerabilities to opportunistic shifts in military allegiance.[2]The Coup of 960 and Transition to Song

In the wake of Emperor Shizong's death on July 27, 959, his seven-year-old son Chai Zongxun ascended the throne as Emperor Gong of Later Zhou, with regents overseeing the young ruler amid ongoing threats from northern powers like Liao and Northern Han. Zhao Kuangyin, a trusted general who had risen through military merit under both Guo Wei and Chai Rong, commanded the elite Palace Frontier Army (殿前司), positioning him as the most powerful figure in the regime and rendering the dynasty vulnerable to internal seizure given the minor emperor's inability to assert authority.[43] Early in 960, intelligence reports—later suspected by some accounts to be fabricated or exaggerated—claimed a massive invasion by Liao forces allied with Northern Han, prompting urgent mobilization of Zhao's 60,000–100,000 troops northward from Kaifeng.[24] As the army encamped at Chenqiao station northeast of the capital on the jiachen day (fourth day) of the first lunar month (approximately February 4 in the Gregorian calendar), Zhao's officers, including his brother Zhao Kuangyi and key subordinates like Murong Yanzhao, staged a bloodless mutiny by draping him in the yellow imperial robe—a symbolic act of reluctant acclamation—proclaiming him emperor to avert perceived chaos from the child's rule and capitalize on the troops' loyalty forged through prior campaigns.[44] This "yellow robe incident" reflected the causal dynamics of military praetorianism in the Five Dynasties era, where generals frequently exploited regency weaknesses and mobilization pretexts to claim the mandate amid fragmented legitimacy.[24] The army promptly reversed course and marched back to Kaifeng, entering the city without opposition as court officials, facing the overwhelming force, offered no resistance beyond minor clashes quelled swiftly.[24] On the eighth day of the first month (circa February 8, 960), Chai Zongxun formally abdicated in the presence of Zhao's entourage, ending the Later Zhou after just nine years and enabling seamless absorption of its administrative and military structures into the nascent Song dynasty under Zhao Kuangyin, now Emperor Taizu.[44] In the immediate transition, Taizu preserved the Chai lineage by enfeoffing the former emperor as Duke of Zheng with estates and stipends, avoiding purges to legitimize continuity while dismantling rival power centers, thus underscoring the coup's inevitability rooted in the dynasty's brief tenure and dependence on charismatic military leadership rather than institutional depth.[24]Rulers and Succession

List of Emperors

The emperors of the Later Zhou dynasty (951–960) were as follows:| Temple Name | Posthumous Name | Personal Name | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taizu (太祖) | - | Guo Wei (郭威; 904–954) | 951–954 | Founding emperor; proclaimed emperor on 16 December 951 after overthrowing the Later Han; died of illness on 22 February 954 without direct heirs, leading to adoption of Chai Rong.[45][6] |

| Shizong (世宗) | - | Chai Rong (柴榮; 921–959), later Guo Rong (郭榮) | 954–959 | Adopted son of Guo Wei; ascended upon predecessor's death; known for military reforms and campaigns; died suddenly on 27 July 959, leaving a young son as heir.[18][24] |

| - | Gongdi (恭帝) | Chai Zongxun (柴宗訓; 953–973), later Guo Zongxun (郭宗訓) | 959–960 | Seven-year-old son of Shizong; nominal rule ended with coup by Zhao Kuangyin on 4 February 960, who established the Song dynasty; abdicated and received title Duke of Song before dying in 973.[46][24] |

Family Tree and Key Relatives

The imperial lineage of Later Zhou originated with Guo Wei (904–954), posthumously Emperor Taizu, who founded the dynasty in 951 after serving as a general under previous regimes but produced no biological heirs. Lacking sons, Guo Wei adopted Chai Rong (921–959) as his successor, renaming him Guo Rong; Chai Rong was the nephew of Guo Wei's wife, Lady Chai (from the Chai clan), being the son of her elder brother Chai Shouli, which established the adoptive connection central to the dynasty's short succession.[47][3] Chai Rong, who reigned as Emperor Shizong from 954 until his death in 959, fathered several sons, with Chai Zongxun (953–973) as the primary heir from his principal consort, Lady Fu. Born in late 953, Chai Zongxun succeeded at age six following his father's sudden illness and ascension as Emperor Gong (r. 959–960), under regency amid the dynasty's military campaigns.[24][48]| Emperor | Birth–Death | Relation to Predecessor | Key Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taizu (Guo Wei) | 904–954 | Founder | No biological sons; adopted Shizong as heir due to infertility or early losses.[3] |

| Shizong (Chai Rong / Guo Rong) | 921–959 | Adoptive son of Taizu | Son of Taizu's brother-in-law Chai Shouli; biological father of Gong. |

| Gong (Chai Zongxun) | 953–973 | Biological son of Shizong | Child emperor deposed in 960 coup; enfeoffed by Song founder Zhao Kuangyin as Duke of Zheng, with initial honors extended to Chai remnants, though executed in 973 during palace intrigue despite assurances of protection.[24][48][49] |