Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Southern Han

View on WikipediaKey Information

| Southern Han | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 南漢 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 南汉 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | South Han | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

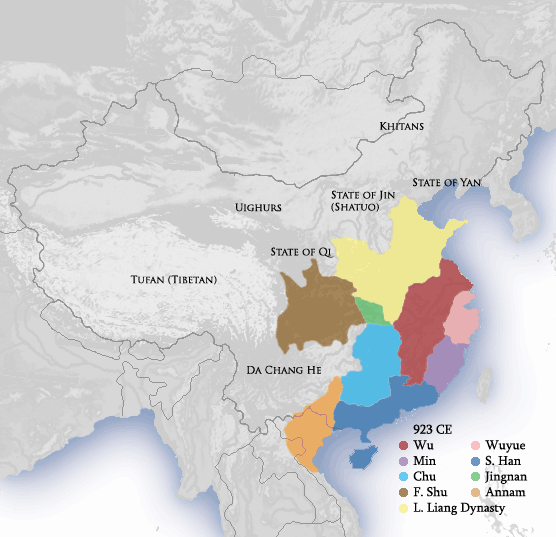

Southern Han (Chinese: 南漢; pinyin: Nán Hàn; Jyutping: Naam4 Hon3; Vietnamese: Nam Hán; 917–971), officially Han (Chinese: 漢), originally Yue (Chinese: 越; Jyutping: Jyut6), was a dynastic state of China and one of the Ten Kingdoms that existed during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. It was located on China's southern coast, controlling modern Guangdong and Guangxi. The dynasty greatly expanded its capital Xingwang Fu (Chinese: 興王府; pinyin: Xìngwáng Fǔ; Jyutping: Hing1wong4 Fu2, present-day Guangzhou). It attempted but failed to annex the autonomous polity of Jinghai, which was controlled by the Vietnamese.

Founding of the Southern Han

[edit]Liu Yin was named regional governor and military officer by the Tang court in 905. Though the Tang fell two years later, Liu did not declare himself the founder of a new kingdom as other southern leaders had done. He merely inherited the title of Prince of Nanping in 909.

It was not until Liu Yin's death in 917 that his brother, Liu Yan, declared the founding of a new kingdom, which he initially called "Yue" (越); he changed the name to Han (漢) in 918. This was because his surname Liu (劉) was the imperial surname of the Han dynasty and he claimed to be a descendant of that famous dynasty. The kingdom is often referred to as the Southern Han dynasty throughout China's history. It attempted but failed to annex the independent polity of Jinghai which was controlled by the Vietnamese.

Territorial extent

[edit]With its capital at present-day Guangzhou, the domains of the kingdom spread along the coastal regions of present-day Guangdong, Guangxi and the island of Hainan. It had borders with the kingdoms of Min, Chu and the Southern Tang as well as the non-Han Chinese kingdoms of Dali. The Southern Tang occupied all of the northern boundary of the Southern Han after Min and Chu were conquered by the Southern Tang in 945 and 951 respectively.

War with the Vietnamese

[edit]

During the late 9th century as the Tang dynasty weakened, local Vietnamese lords began taking control of its domain in Jinghai (northern Vietnam). Southern Han campaigned twice against the Vietnamese in 931 and 938 in an attempt to add these Vietnamese territories to their realm, but failed both.[1][2]

Fall of the Southern Han

[edit]The Five Dynasties ended in 960 when the Song dynasty was founded to replace the Later Zhou. From that point, the new Song rulers set themselves about to continue the reunification process set in motion by the Later Zhou. Through the 960s and 970s, the Song increased its influence in the south until finally it was able to force the Southern Han dynasty to submit to its rule in 971.

Rulers

[edit]| Temple Names | Posthumous Names | Personal Names | Period of Reigns | Era Names |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gao Zu (高祖 gāo zǔ) | Tian Huang Da Di (天皇大帝 tiān huáng dà dì) | Liu Yan (劉巖 liú yán)

Liu Yan (劉龑 liú yǎn) after 926 |

917–941 | Qianheng (乾亨 qián hēng) 917–925 Bailong (白龍 bái lóng) 925–928 |

| Did not exist | Shang Di (殤帝 shāng dì) | Liu Bin (劉玢 liú bīn) | 941–943 | Guangtian (光天 guāng tiān) 941–943 |

| Zhong Zong (中宗 zhōng zōng) | Wénwǔ Guāngmíng Xiào (文武光明孝皇帝)

Too tedious thus not used when referring to this sovereign |

Liu Sheng (劉晟 liú shèng) | 943–958 | Yingqian (應乾 yìng qián) 943 Qianhe (乾和 qiàn hé) 943–958 |

| Hou Zhu (後主 hòu zhǔ) | Did not exist | Liu Chang (劉鋹 liú chǎng) | 958–971 | Dabao (大寶 dà bǎo) 958–971 |

Rulers family tree

[edit]| Southern Han rulers family tree | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Coedes 2015, p. 80.

- ^ Taylor 1983, p. 269.

Sources

[edit]- Mote, F.W. (1999). Imperial China (900–1800). Harvard University Press. pp. 11, 15. ISBN 0-674-01212-7.

- Schafer, Edward H. "The History of the Empire of Southern Han: According to Chapter 65 of the Wu-tai-shih of Ou-yang Hsiu", Zinbun-kagaku-kenkyusyo (ed.), Silver Jubilee Volume of the Zinbun-kagaku-kenkyusyo. Kyoto, Kyoto University, 1954.

- Tarling, Nicholas, ed. (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia (Volume One, Part One): From early times to c. 1500. Cambridge University Press. p. 139. ISBN 0-521-66369-5.

- Coedes, George (2015). The Making of South East Asia (RLE Modern East and South East Asia). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317450955.

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1983), The Birth of the Vietnam, University of California Press, ISBN 9780520074170

Southern Han

View on GrokipediaHistory

Founding

The foundations of Southern Han were laid by Liu Yin (874–911), who built a power base in the Lingnan region during the political fragmentation after the Tang dynasty's fall in 907. Originally from Shangcai in modern Henan or Pengcheng in Jiangsu, Liu Yin and his brother relocated southward, with their father serving as regional inspector of Fengzhou near modern Wuzhou in Guangxi. In 905, Liu Yin received appointment as military commissioner (jiedushi) of the Qinghai Circuit, centered on Guangzhou (ancient Panyu). The succeeding Later Liang regime confirmed his authority, granting him the title of king of Dapeng Commandery in 907 and later king of Nanping in 909, allowing him to govern effectively over Guangdong and parts of Guangxi through military and administrative control.[1] Following Liu Yin's death in 911, his younger brother Liu Yan (889–942) assumed control of the territories. Liu Yan maintained and expanded this autonomy amid the Five Dynasties' instability, drawing on local resources, a standing army, and naval forces inherited from his brother. In 917, Liu Yan declared himself emperor, inaugurating the kingdom as Great Yue (大越) with Panyu as capital, thereby asserting full independence from nominal northern overlords. The following year, 918, he renamed the state Great Han (大漢), a move justified by his surname Liu, shared with the Han dynasty's imperial house, to legitimize his rule through historical continuity—a tactic employed by several contemporaneous regimes.[1][2][3] This establishment reflected the broader pattern of regional warlords exploiting the Tang collapse to form enduring polities, with Southern Han's southern isolation and maritime orientation enabling relative stability in its early years.[1]Territorial expansion and extent

The Southern Han kingdom was founded in 917 by Liu Yan, who inherited control over the Lingnan region from his brother Liu Yin, encompassing primarily the areas of modern Guangdong and Guangxi provinces, with Guangzhou as the capital.[4][2] This core territory corresponded to the former Qingwang military circuit under the Tang dynasty, which included commanderies along the Pearl River Delta and extending westward into Guangxi.[5] Expansion efforts focused southward and occasionally northward, with Liu Yan launching campaigns to subdue local non-Han tribes and assert dominance over Hainan Island, incorporating it into the kingdom's domain by the early 10th century.[2] In 930, Southern Han armies under generals Liang Kezhen and Li Shoufu captured Jiao Prefecture (modern northern Vietnam), briefly extending the kingdom's influence into Annam before suffering a decisive naval defeat at the Battle of Bạch Đằng River in 938, led by Ngô Quyền, which curtailed further southern advances.[6] Northward, conflicts with the Chu kingdom in Hunan and the Min kingdom in Fujian yielded limited territorial gains, as Southern Han prioritized consolidation amid frequent border skirmishes; its borders ultimately abutted Chu to the northwest, Min and later Southern Tang to the northeast, and non-Han polities like Dali to the west.[2] At its peak under Emperor Liu Sheng (r. 943–958), the kingdom maintained control over approximately 200,000 square kilometers, leveraging coastal access and naval capabilities to defend this extent against larger northern rivals.[4]Wars and foreign relations

Southern Han pursued expansion southward into Annam, corresponding to modern northern Vietnam, as part of its efforts to consolidate control over Lingnan and adjacent territories. In 930, Emperor Liu Yan dispatched an army that occupied Dai-la, the capital of Dai Co Viet, imposing direct rule over the region.[7] This ambition culminated in a major naval invasion in late 938, when a Southern Han fleet under Liu Hongcao advanced up the Bạch Đằng River. Vietnamese forces led by Ngô Quyền ambushed the invaders by driving iron-tipped wooden stakes into the riverbed, which emerged at low tide and impaled the grounded warships during the Southern Han retreat, resulting in heavy losses and the fleet's destruction.[8] The defeat at Bạch Đằng marked the failure of Southern Han's southern campaigns and contributed to Annam's emergence as an independent polity under Ngô Quyền.[7] To the north, Southern Han maintained rivalrous relations with the Kingdom of Chu, including repelling a Chu naval assault on Feng Prefecture in 928. Following Chu's annexation by Southern Tang in 951, Southern Han's northern frontier shifted to face the expanding Southern Tang, though no large-scale wars ensued before Song unification efforts.[1] The kingdom's independence ended with the Song Dynasty's conquest in 970–971. Song general Pan Mei led an expeditionary force that advanced through the region, capturing the capital Guangzhou in 971 and compelling the surrender of the last ruler, Liu Jixing.[1][9] This campaign integrated Southern Han's territories into the unified Song empire, concluding the era of the Ten Kingdoms in the south.[1]Decline and fall

The later years of Southern Han were marked by deepening internal decay, particularly under Emperor Liu Chang (r. 958–971), whose reign saw eunuchs exert dominant control over provincial administration, eroding the central government's authority and military effectiveness.[1] Heavy taxation to fund extravagant constructions, such as the opulent Zhaoyang Hall, fueled widespread discontent and sporadic rebellions, including the 942 uprising led by Zhang Yuxian among fisherfolk, who proclaimed himself "King of the Eight Countries" before being suppressed.[1] These factors compounded the dynasty's longstanding issues of court luxury and administrative corruption inherited from founder Liu Yan, leaving Southern Han vulnerable as the Song Dynasty unified northern China following its establishment in 960.[1] The Song Dynasty, under Emperor Taizu, launched its southern campaigns to consolidate control over the remnants of the Ten Kingdoms. In late 970, Song forces under general Pan Mei advanced into Southern Han territory, capturing key prefectures like Shaozhou by early 971 despite initial resistance from Southern Han's naval and elephant-based armies.[1] A decisive engagement on January 23, 971, near Guangzhou saw Song crossbowmen employ massed arrow fire to rout Southern Han's war elephant corps, a tactic that exploited the animals' vulnerability to projectiles and disrupted their charge.[10] Facing imminent collapse, Liu Chang surrendered to Song forces in May 971, formally ending Southern Han after 54 years of rule; he was granted the title of marquis and relocated to the Song capital at Kaifeng, where he died in 980.[1] The conquest integrated Southern Han's territories—encompassing modern Guangdong, Guangxi, and parts of Hainan—into the Song empire, marking the dynasty's absorption without prolonged siege due to its internal frailties.[1]Government and administration

Central institutions

The central government of Southern Han operated from the capital at Panyu, redesignated as Xingwang prefecture under founder Liu Yan, who proclaimed himself emperor in 918 CE. This structure emphasized a civilian bureaucracy to counterbalance military influences prevalent in the fragmented post-Tang era, with the emperor holding supreme authority over policy, appointments, and edicts.[1] Annual civil service examinations were instituted to recruit officials, fostering a merit-based system that prioritized scholarly administrators over hereditary or martial elites, thereby sustaining administrative continuity across reigns from Liu Yan (917–942) to Liu Chang (958–971). Oversight mechanisms, including the Censorate for auditing officials and the Remonstrance Bureau for policy critique, functioned within this framework to enforce accountability and advise the throne.[1][11] However, institutional efficacy eroded in the later period, particularly under Liu Chang, as eunuch factions gained sway over appointments and decisions, undermining the civilian ethos despite formal examination protocols. Regional inspectors (cishi) and commissioners reported to central authorities, but de facto power often shifted toward palace insiders, reflecting broader dynastic vulnerabilities.[1]Provincial control and eunuch influence

The Southern Han administration divided its territory into approximately 15 prefectures (zhou), with governors (cishi) appointed centrally from the capital at Panyu (modern Guangzhou) to oversee local taxation, judicial affairs, and military garrisons.[1] These officials were primarily recruited through annual civil service examinations, a policy initiated by founder Liu Yan (r. 917–942) to foster a civilian bureaucracy and curb militaristic tendencies inherited from the Tang dynasty's fragmentation.[1] This system aimed to centralize authority by rotating appointees and emphasizing loyalty to the Liu imperial house, though heavy taxation to fund palace luxuries often provoked local unrest, as seen in the 942 rebellion led by Zhang Yuxian in Xunzhou prefecture, which required direct imperial intervention to suppress.[1] Eunuch influence emerged as a corrosive factor particularly under the last ruler, Liu Chang (r. 958–971), who relied on palace eunuchs for personal counsel and administrative oversight, granting them de facto control over court decisions and resource allocation.[1] These eunuchs, unencumbered by familial ties and positioned close to the emperor, manipulated appointments to provincial posts, favoring loyalists who prioritized tribute flows over effective governance, thereby eroding the merit-based recruitment Liu Yan had established.[1] This shift weakened central oversight, as provincial governors increasingly acted with autonomy amid ongoing rebellions and external pressures, such as invasions from the Kingdom of Chu in 948, exacerbating fiscal strains and military disarray.[1] By the 960s, eunuch dominance had fragmented administrative cohesion, with reports of corruption in prefectural management contributing to the dynasty's vulnerability; this internal decay facilitated the Song dynasty's conquest in 971, when Liu Chang surrendered after minimal resistance from disorganized provincial forces.[1] The eunuch system's amplification of court intrigue over provincial stability echoed patterns in earlier Chinese dynasties but proved fatal in the competitive Ten Kingdoms landscape, where robust central-provincial integration was essential for survival.[1]Military

Organization and forces

The Southern Han military relied on a standing professional army inherited from the Liu clan's control of the Qinghai military circuit under the late Tang system, where regional commanders (jiedushi) maintained personal forces funded through local taxes and salt monopolies. These troops, numbering in the tens of thousands, were primarily infantry supplemented by cavalry and local levies from Han settlers and indigenous groups in Lingnan, such as the Yao and Zhuang peoples, reflecting the kingdom's ethnic diversity and reliance on regional recruitment for defense against northern incursions.[1] Command was centralized under the emperor and his relatives, with key generals like Liu Cheng leading expeditions, as seen in the 948 invasion of Chu that captured ten prefectures through coordinated assaults.[1] A distinctive feature of Southern Han forces was the incorporation of war elephants, sourced from the tropical south, which served as shock troops in battles but proved vulnerable to massed archery; during the Song conquest in 971, Song crossbow volleys routed these units near Guangzhou, contributing to the kingdom's rapid collapse.[12] Internal vulnerabilities were evident in events like the 942 rebellion led by Zhang Yuxian, where fisherfolk militias initially overwhelmed regular troops before being suppressed, highlighting uneven discipline and loyalty issues amid eunuch influence over appointments.[1]Naval capabilities and campaigns

The Southern Han maintained a substantial naval force, essential for controlling riverine territories along the Pearl River system and coastal regions facing the South China Sea, as evidenced by early rulers like Liu Qian who commanded both armies and fleets in regional inspections.[1] This navy supported defensive operations, suppression of internal rebellions involving aquatic elements such as fisherfolk uprisings in 942, and offensive projections beyond core territories.[1] The kingdom's most notable naval campaign occurred in 938, when Emperor Liu Yan dispatched a fleet to reconquer the Annam (Giao Châu) region, previously under loose Chinese suzerainty, aiming to reassert dominance over northern Vietnam.[8] Commanded by Liu Hongcao, a Southern Han prince, the expedition advanced up the Bạch Đằng River but encountered Vietnamese forces led by Ngô Quyền, who had planted iron-tipped wooden stakes in the riverbed exposed at low tide.[8] As the tide receded during the retreat, the Southern Han ships impaled on the stakes, leading to heavy losses including the death of Liu Hongcao and the destruction of much of the fleet, marking a decisive Vietnamese victory and the end of Southern Han's direct military ambitions in Annam.[8] Naval elements also played roles in border conflicts, such as clashes with the Chu kingdom on eastern frontiers and the 948 invasion led by Liu Cheng that captured ten prefectures, likely involving riverine assaults given the terrain.[1] By the kingdom's fall in 971, Southern Han naval capabilities proved insufficient against the Song dynasty's combined forces, which overcame river defenses to compel Emperor Liu Sheng's surrender at Guangzhou.[1] The navy's emphasis on coastal and fluvial warfare reflected Southern Han's geographic constraints but highlighted its reliance on maritime power for survival amid fragmented southern polities.Economy

Agriculture and resources

The agriculture of Southern Han relied primarily on wet-rice cultivation in the irrigated lowlands and river deltas of Guangdong and Guangxi, where the subtropical climate enabled double-cropping and supported population growth through high yields from the Pearl River system.[13] Farmers employed traditional techniques including water buffalo plowing and embankment systems to manage flooding and salinity in coastal areas. Supplementary crops such as millet, beans, and tropical fruits like lychees contributed to dietary diversity, though rice remained the staple grain dominating caloric intake.[14] Key natural resources included pearls harvested from coastal waters, with organized pearl farming operations established during the reign of Liu Yan (917–942) in regions such as the coasts near modern Sai Kung, Sha Tin, Tai Po, and Lei Yue Mun, supplying luxury goods for domestic elite consumption and export.[15][16] Salt production from evaporated seawater ponds along the Gulf of Tonkin and South China Sea shores provided another vital resource, often regulated by the state to generate revenue, akin to practices in contemporaneous southern kingdoms. Fisheries yielded seafood and aquatic products, while inland areas offered timber and limited mineral deposits like tin, though extraction remained modest compared to agricultural output.[17]Trade and maritime activities

The Southern Han kingdom's economy heavily relied on maritime trade centered in Guangzhou, a pivotal port on the Maritime Silk Road that connected Lingnan to Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean.[18] Rulers actively sponsored overseas commerce, exchanging Chinese exports such as silk, porcelain, and metals for imports including spices, ivory, aromatics, and pearls from regions like Annam, Java, and Arab territories.[19] This trade generated substantial revenue through tariffs, state monopolies on salt and foreign goods, and direct court involvement, underpinning the kingdom's prosperity amid regional fragmentation.[20][21] Emperor Liu Yan (r. 917–942) established specialized administrative offices, such as the City Shipping Supervisorate (shibo si), to regulate sea traffic, oversee foreign merchants, and facilitate tributary and private exchanges.[20][18] Iranian and Arab Muslim traders formed established communities in Guangzhou, contributing to a cosmopolitan maritime hub that persisted from Tang precedents into the Southern Han era. The court's strategic emphasis on marine affairs included alliances and military actions to secure trade routes, such as Liu Yan's marriage ties with neighboring rulers and naval expeditions to counter threats.[22] Southern Han's naval capabilities directly supported commercial activities, with fleets protecting coastal waters and projecting power southward; in 928, Liu Yan dispatched 100 warships to repel invaders from Chu state territories in northwest Guangdong.[23] Archaeological finds, including shipwrecks off Guangdong with Southern Han ceramics and trade goods, confirm active state participation in long-distance voyages beyond mere facilitation.[22] Despite eunuch influence over monopolies potentially stifling broader merchant participation, the kingdom's maritime orientation distinguished it from inland-focused contemporaries, fostering economic resilience until Song conquest in 971.[19]Society and culture

Social hierarchy and ethnic composition

The social hierarchy of Southern Han adhered to Confucian ideals prevalent in contemporary Chinese states, featuring the emperor as the supreme authority, supported by a nobility and scholar-officials who managed administration and landholdings. Eunuchs exerted considerable influence within the court, often mediating between the ruler and bureaucracy, reflecting a structure where familial and bureaucratic loyalty superseded meritocratic ideals. Peasants formed the economic foundation through rice cultivation in the fertile Pearl River Delta, while artisans crafted luxury items like ceramics and silks for elite consumption, and merchants prospered from overseas trade, occasionally elevating their status beyond traditional disdain in Confucian rankings.[24] Ethnic composition varied regionally, with Han Chinese migrants and their descendants dominating the ruling class and urban centers such as Guangzhou, where they imposed centralized control and orthodox Confucianism. In rural and peripheral areas of Lingnan, indigenous populations descended from ancient Baiyue groups persisted, including ancestors of the Zhuang people who inhabited Guangxi and northern Vietnam borderlands. These non-Han groups, often organized in tribal structures, supplied tribute and labor but experienced partial assimilation via intermarriage and administrative integration, though cultural distinctions remained pronounced.[25]Cultural patronage and developments

The emperors of Southern Han, particularly founder Liu Yan (r. 917–942), were noted for their patronage of grandiose architecture, constructing extravagant palaces that symbolized imperial authority and luxury. Zhaoyang Hall (昭陽殿), for instance, featured a roof covered in gold, reflecting the regime's emphasis on opulent displays amid regional prosperity from maritime trade.[1] This architectural indulgence extended to religious sites, with Liu Yan commissioning the Dafo Temple (大佛寺, Grand Buddha Temple) in Guangzhou during his reign, establishing it as a major Buddhist sanctuary that integrated Lingnan regional styles with central Chinese influences.[26] Buddhism received significant court support, fostering developments in temple construction and devotional practices tailored to southern China's diverse ethnic milieu. The Dafo Temple's founding under Liu Yan's direct patronage underscores this, as the emperor allocated resources for its establishment amid a broader Five Dynasties trend of lay and imperial sponsorship of Buddhist infrastructure to legitimize rule and accrue spiritual merit.[27] Surviving artifacts from Southern Han mausoleums, including those of Liu Yan excavated between 2003 and later, reveal ceramic figurines and tomb decorations depicting musicians and dancers, indicating active court patronage of performing arts such as pipa music and ensemble performances.[28][29] Literary and scholarly culture benefited from institutionalized mechanisms like annual state examinations, which Liu Yan and successors maintained to recruit officials and cultivate Confucian erudition, preventing over-reliance on military elites.[1] This system supported a modest flourishing of textual production in the capital at Xingwangfu (modern Guangzhou), though overshadowed by the dynasty's reputational focus on hedonism and eunuch-dominated intrigues rather than prolific literary output comparable to northern contemporaries.Rulers

List of emperors

The emperors of Southern Han, ruling from 917 to 971, were members of the Liu family, with succession marked by familial murders and brief reigns amid internal instability.[1]| Temple Name | Personal Name | Era Names | Reign Years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaozu (高祖) | Liu Yan (劉巖) | Qianheng (乾亨, 917–924); Bailong (白龍, 925–927); Dayou (大有, 928–941) | 917–942 |

| Shangdi (殤帝) | Liu Fen (劉玢) | Guangtian (光天, 942) | 942 |

| Zhongzong (中宗) | Liu Cheng (劉晟) | Yingqian (應乾, 943); Qianhe (乾和, 943–957) | 943–958 |

| Houzhu (後主) | Liu Chang (劉鋹) | Dabao (大寶, 958–971) | 958–971 |