Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Leeuwin Current

View on Wikipedia

The Leeuwin Current is a warm ocean current which flows southwards near the western coast of Australia. It rounds Cape Leeuwin to enter the waters south of Australia where its influence extends as far as Tasmania.

Discovery

[edit]

The existence of the current was first suggested by William Saville-Kent in 1897. Saville-Kent noted the presence of warm tropical water offshore in the Houtman Abrolhos, making the water there in winter much warmer than inshore at the adjacent coast. The existence of the current was confirmed over the years, but not characterised and named until Cresswell and Golding did so in the 1980s.[1]

Track

[edit]The West Australian Current and Southern Australian Countercurrent, which are produced by the West Wind Drift on the southern Indian Ocean and at Tasmania, respectively, flow in the opposite direction, producing one of the most interesting oceanic current systems in the world.

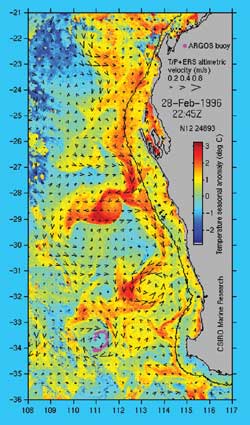

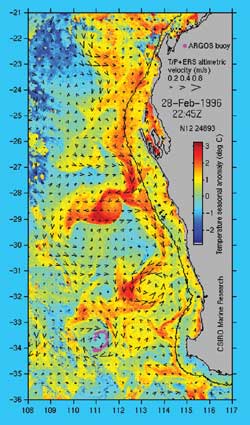

The ‘core’ of the Leeuwin Current can generally be detected as a peak in the surface temperature with a strong temperature decrease further offshore. The surface temperature difference across the Current is about 1 °C at North West Cape, 2° to 3° at Fremantle and can be over 4° off Albany in the Great Australian Bight. The current frequently breaks out to sea, forming both clockwise and anti-clockwise eddies.

Physical properties

[edit]Its strength varies through the year; it is weakest during the summer months (winter in the northern hemisphere) from November to March when the winds tend to blow strongly from the south west northwards. The greatest flow is in the autumn and winter (March to November) when the opposing winds are weakest. Evaporation from the Leeuwin current during this period contributes greatly to the rainfall in the southwest region of Western Australia.

Typically the Leeuwin Current's speed and its eddies are about 1 knot (50 cm/s), although speeds of 2 knots (1 m/s) are common, and the highest speed ever recorded by a drifting satellite-tracked buoy was 3.5 knots (6.5 km/h). The Leeuwin Current is shallow for a major current system, by global standards, being about 300 m deep, and lies on top of a northwards countercurrent called the Leeuwin Undercurrent.

Because of the Leeuwin Current, the continental shelf waters of Western Australia are warmer in winter and cooler in summer than the corresponding regions off the other continents. The Leeuwin Current is also responsible for the presence of the most southerly true corals at the Abrolhos Islands and the transport of tropical marine species down the west coast and across into the Great Australian Bight.

The Leeuwin Current is influenced by El Niño conditions, characterised by slightly lower sea temperatures along the Western Australian coast and a weaker Leeuwin Current, with corresponding effects upon rainfall patterns.

Comparisons

[edit]The Leeuwin Current is very different from the cooler, equatorward flowing currents found along coasts at equivalent latitudes such as the southwest African Coast (the Benguela Current); the long Chile-Peru Coast (the Humboldt Current), where upwelling of cool nutrient-rich waters from below the surface results in some of the most productive fisheries; the California Current, which brings foggy conditions to San Francisco; or the cool Canary current of North Africa.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pearce, A. F. (1997). "The Leeuwin Current and the Houtman Abrolhos Islands, Western Australia". In Wells, F. E. (ed.). The Marine Flora and Fauna of the Houtman Abrolhos Islands, Western Australia, Volume 1. Perth: Western Australian Museum. pp. 11–46.

Further reading

[edit]- (1996) Scientists identify a counter current known as the Capes Current flowing against the Leeuwin Current Western fisheries, Winter 1996, p. 44-45

- Greig, M. A. (1986) The "Warreen" sections : temperatures, salinities, densities and steric heights in the Leeuwin Current, Western Australia, 1947-1950 Hobart : Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation Marine Research Laboratories, Report / CSIRO Marine Laboratories, 0725-4598 ; 175. ISBN 0-643-03656-3

- Pearce, Alan (2000) "Lumps" in the Leeuwin Current and rock lobster settlement. Western fisheries magazine, Winter 2000, p. 47-49