Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

London Array

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

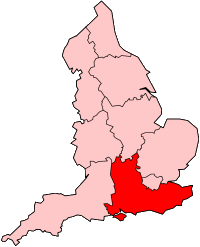

The London Array is a 175-turbine 630 MW Round 2 offshore wind farm located 20 kilometres (12 mi) off the Kent coast in the outer Thames Estuary in the United Kingdom. It was the largest offshore wind farm in the world until Walney Extension reached full production in September 2018.

Construction of phase 1 of the wind farm began in March 2011 and was completed by mid 2013, being formally inaugurated by the Prime Minister, David Cameron on 4 July 2013.

The second phase of the project was refused planning consent in 2014 due to concerns over the impact on sea birds.

Description

[edit]The wind farm site is more than 20 kilometres (12 mi) off the North Foreland on the Kent coast. It is in the area between Long Sand and Kentish Knock, between Margate in Kent and Clacton in Essex.[3] The site has water depths of no more than 25 m[1] and is mostly away from deep water shipping lanes.[4] It is north of the shallow cross estuary channel, the Fisherman's Gat and astride of the Foulger's Gat.

The first phase consisted of 175 Siemens Wind Power SWT-3.6 turbines and two offshore substations, giving a wind farm with a peak rated power of 630 MW.[5] Each turbine and offshore substation is erected on a monopile foundation, and connected together by 210 km (130 mi) of 33 kV array cables. The two offshore substations are connected to an onshore substation at Cleve Hill (near Graveney) on the north Kent coast, by four 150 kV subsea export cables, in total 220 km (140 mi).[5] It is named after London because the power goes to the London grid.[6]

The smaller Thanet Wind Farm is to the south.

The array is intended to reduce annual CO2 emissions by about 900,000 tons, equal to the emissions of 300,000 passenger cars.[7]

History

[edit]In 2001 environmental studies identified areas of the outer Thames Estuary as potential sites for offshore wind farms;[8] the Department of Trade and Industry published the paper Future Offshore — A Strategic Framework for the Offshore Wind Industry, which identified the outer Thames Estuary as one of three potential areas for future wind farm development (Round 2 wind farms).[9] The Crown Estate awarded a 50-year lease to London Array Ltd (a consortium of E.ON UK Renewables, Shell WindEnergy, and CORE Limited[note 1]) in December 2003.[8][12] A planning application was submitted in 2005,[12][13] which was approved in December 2006.[14] Planning permission for the onshore electricity substation was granted in November 2007.[11]

In May 2008, Shell announced that it was pulling out of the project.[15] It was announced in July 2008 that E.ON UK and DONG Energy would buy Shell's stake.[16] Subsequently, on 16 October 2008, London Array announced the Abu Dhabi based Masdar would join E.ON as a joint venture party in the scheme. Under the agreement, Masdar purchased 40% of E.ON's half share of the scheme, giving Masdar a 20% stake in the project overall.[17][18] The resultant ownership was 50% DONG Energy, 30% E.ON UK Renewables and 20% Masdar.[19]

In March 2009, the backers agreed on an initial investment of €2.2 billion.[20] Financing of phase 1 was achieved through the European Investment Bank and the Danish Export Credit Fund with £250 million.[19]

In 2013, in response to Ofgem "Offshore Transmission Owner" regulations, the consortium divested the electrical transmission assets of the wind farm (valued at £459 million) to Blue Transmission London Array Limited – an entity incorporated by Barclays Infrastructure Funds Management Limited (Barclays) and Diamond UK Transmission Corporation (a Mitsubishi Corporation subsidiary).[21]

In January 2014, DONG sold half its stake to Quebec public pension plan manager Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec ("La Caisse"),[22] and in 2023 sold its remaining 25% share to Schroders Greencoat for £717 million (£4.56 m/MW).[23] Following RWE's takeover of E.ON's power generation in an asset swap in 2019, RWE now owns the 30% stake previously belonging to E.ON.

At the time of its construction, it was the largest offshore wind farm in the world.[24]

Construction and commissioning

[edit]Offshore work began in March 2011[25] with construction of the first foundation.[26]

Turbines were supplied by Siemens Wind Power.[27] Their foundations were built by a joint-venture between Per Aarsleff and Bilfinger Berger Ingenieurbau GmbH. The same company supplied and installed the monopiles.[28] Generators were installed by MPI and A2SEA, using an installation vessel TIV MPI Adventure and a jack-up barge Sea Worker.[29] Two offshore substations were designed, fabricated and installed by Future Energy, a joint venture between Fabricom, Iemants and Geosea, while electrical systems and onshore substation work was undertaken by Siemens Transmission & Distribution. The subsea export cable was supplied by Nexans and array cables by JDR Cable Systems. The array cables and the export cables were installed by VSMC.[28]

The wind farm started producing electricity at the end of October 2012.[25] All 175 turbines of phase 1 were confirmed fully operational on 8 April 2013,[30] and the wind farm was formally inaugurated by the Prime minister David Cameron on 4 July 2013.[31] In December 2015 it produced 369 GWh, a monthly capacity factor of 78.9%. It produced 2.5 TWh in 2015. During two days of January 2016, production varied from 3 MW to 619 MW.[32][33]

Its levelised cost has been estimated at £140/MWh.[34]

Phase 2

[edit]A second phase was planned which would have seen a further 166 turbines installed to increase the capacity to 1000 MW.[35] However, the second phase was scaled back and finally cancelled in February 2014 after concerns were raised by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds about its effect on a local population of red-throated divers.[35][36]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "London Array Offshore Wind Farm". 4coffshore.com. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ "London Array breaks offshore production record". Archived from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- ^ "Preliminary Information Memorandum: London Array (Phase 1) Offshore Transmission Assets" (PDF). Ofgem. November 2010. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ^ Harris, Stephen. Your questions answered: The London Array Archived 19 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine The Engineer (UK magazine), 19 November 2013.

- ^ a b Nathan 2012

- ^ Fehrenbacher, Katie. The massive London Array offshore ppwind farm Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine is finally done and it’s awesome] Gigaom, 8 July 2013.

- ^ "London Array Offshore Windfarm Inaugurated", www.marinelink.com, 5 July 2013, archived from the original on 10 July 2013, retrieved 7 July 2013

- ^ a b The London Array (London Array), p.6

- ^ Future Offshore -A Strategic Framework for the Offshore Wind Industry (PDF), Department of Trade and Industry, November 2002, p.9; table 2.2, p.26; 4.3.3, pp.41-43; table 4.1, p41; fig.4.1, p.42, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2014

- ^ "DONG Energy London Array Limited", opencorporates.com, archived from the original on 22 December 2015, retrieved 17 August 2016

- ^ a b London Array welcomes latest government permissions (press release), 7 November 2007, archived from the original on 12 May 2014, retrieved 11 May 2014

- ^ a b "Plan for massive Thames wind farm", BBC News, 7 June 2005, archived from the original on 30 October 2005, retrieved 11 May 2014

- ^ ES Non-technical summary (June 2005)

- ^ "Offshore wind farms get go-ahead", BBC News, 18 December 2006, archived from the original on 26 April 2009, retrieved 11 May 2014

- ^ Shell pulls out of key wind power project, Financial Times, 1 May 2008, archived from the original on 1 May 2008, retrieved 1 May 2008

- ^ "E.ON and DONG Energy become 50:50 partners in world's largest offshore wind farm" (Press release). E.ON. 21 July 2008. Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ Milner, Mark (17 October 2008). "Abu Dhabi buys 20% of London Array". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

initially, it was to have been developed by E.ON, Dong Energy and Shell, but Shell pulled out this year, arguing that the scheme did not meet its financial rates of return. The remaining partners subsequently raised their 33% stakes to 50%.

- ^ "Masdar to invest in London Array offshore wind farm as first step of a global renewable energy partnership with E.ON" (Press release). E.ON. 16 October 2008. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014.

- ^ a b Mette Buck, Jensen (9 June 2010), Dong låner 2,2 milliarder kroner til britisk vindmølleeventyr (in Danish), Ingeniøren (ing.dk), archived from the original on 11 January 2012, retrieved 9 June 2010

- ^ Teather, David (13 May 2009), "Thames offshore wind farm gets green light from investors", The Guardian, archived from the original on 31 December 2013, retrieved 12 December 2016

- ^ Disposal of transmission assets at London Array, the world's largest offshore wind farm (press release), Dong Energy, 10 September 2013, archived from the original on 11 May 2014, retrieved 11 May 2014

- ^ "Dong sells half of its London Array stake", www.utilityweek.co.uk, 31 January 2014, archived from the original on 3 March 2016, retrieved 11 May 2014

- ^ Memija, Adnan (24 July 2023). "Ørsted Divests Remaining Stake in London Array for EUR 829 Million". Offshore Wind.

- ^ Platt, Edward (28 July 2012), "The London Array: the world's largest offshore wind farm", The Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 29 September 2014, retrieved 3 April 2018

- ^ a b Bradbury, John (5 November 2012). "First power from London Array". Offshore.no • International. Offshore Media Group. Archived from the original on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ^ First foundation installed at London Array (PDF) (press release), 8 March 2011, archived from the original on 11 March 2012

- ^ "Siemens to provide 175 wind turbines for the world's largest offshore wind farm London Array" (Press release). Siemens AG. 19 May 2009. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ a b Pitt, Anthea (14 December 2009). "Trio hand out London Array prizes". Upstream Online. NHST Media Group. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2010.(subscription required)

- ^ "London Array signs final major installation contracts for phase one" (Press release). London Array. 4 February 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Hip Hip Array-World's largest offshore wind farm goes fully operational". www.renewableuk.com (Press release). RenewableUK. 8 April 2013. Archived from the original on 12 July 2013.

- ^ Al Makahleh, Shehab (4 July 2013). "London Array, world's largest offshore wind farm, inaugurated" (Press release). gulfnews.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "London Array - Renewable Energy Record Achieved at London Array". London Array. Archived from the original on 1 September 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ "London Array breaks offshore production record". Windpower Monthly. 8 January 2016. Archived from the original on 6 November 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ Aldersey-Williams, John; Broadbent, Ian; Strachan, Peter (2019). "Better estimates of LCOE from audited accounts – A new methodology with examples from United Kingdom offshore wind and CCGT". Energy Policy. 128: 25–35. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.12.044. hdl:10059/3298. S2CID 158158724.

- ^ a b "Sea bird halts London Array wind farm expansion", BBC News, 19 February 2014, archived from the original on 20 April 2018, retrieved 20 June 2018

- ^ Smith, Patrick (19 February 2014), "London Array phase 2 extension scrapped", www.windpoweroffshore.com, archived from the original on 19 June 2014, retrieved 11 May 2014

Notes

[edit]Sources

[edit]- Nathan, Stuart (25 June 2012). "The Big Project: London Array". The Engineer.

- Environmental Statement - Non-technical summary (PDF), London Array Ltd., June 2005, archived from the original (PDF) on 26 May 2013

- London Array - the world's largest offshore wind farm (PDF), London Array Ltd., archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2011

- "London Array Phase 1", www.4coffshore.com