Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Second Sunday of Easter

View on Wikipedia| Second Sunday of Easter | |

|---|---|

| Observed by | Christians |

| Observances | Church services |

| Date | Sunday after Easter Sunday |

| 2025 date |

|

| 2026 date |

|

| 2027 date |

|

| 2028 date |

|

The Second Sunday of Easter is the eighth day of the Christian season of Eastertide, and the seventh after Easter Sunday.[1] It is known by various names, including Divine Mercy Sunday,[2][3] the Octave Day of Easter, White Sunday[a] (Latin: Dominica in albis), Quasimodo Sunday, Bright Sunday and Low Sunday.[1][4] In Eastern Christianity, it is known as Antipascha, New Sunday, and Thomas Sunday.

Biblical account

[edit]

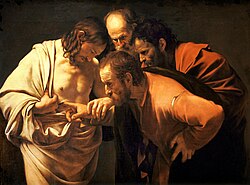

The Second Sunday of Easter is the eighth day after Easter using the mode of inclusive counting, according to which Easter itself is the first day of the eight. Christian traditions which commemorate this day recall the Biblical account recorded to have happened on the same eighth day after the original Resurrection.

Eight days later, his disciples were again in the house, and Thomas was with them. The doors were shut, but Jesus came and stood among them, and said, "Peace be with you." Then he said to Thomas, "Put your finger here, and see my hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side; do not be faithless, but believing." Thomas answered him, "My Lord and my God!" Jesus said to him, "Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe."

It is because of this Scriptural episode that this day is called Thomas Sunday in the Eastern tradition.[5]

Western Christianity

[edit]Names

[edit]White Sunday

[edit]In early Roman Rite liturgical books, Easter Week used to be known as "White Week" (Latin: Ebdomada alba), because of the white robes worn during that week by those who had been baptized at the Easter Vigil.[6] A pre-Tridentine edition of the Catholic Church's Roman Missal, published in 1474, called Saturday in albis, short for in albis depositis or in albis deponendis (of removal of the white garments), a name that was kept in subsequent Tridentine versions of the missal for that Saturday. In the 1604 edition of the Tridentine missal (but not in the original 1570 edition), the description in albis was applied also to the following Sunday, the octave day of Easter.[7]

The 1962 Roman Missal (still in limited use today) refers to this Sunday as Dominica in albis in octava Paschæ.[8] The name in albis was dropped in the 1970 revision.

Quasimodo Sunday

[edit]

The name Quasimodo (or Quasimodogeniti) originates from the incipit of this day's traditional Latin introit,[4] which is based on 1 Peter 2:2.

Quasi modo géniti infántes, allelúia: rationábile, sine dolo lac concupíscite, allelúia, allelúia, allelúia.[8]

Translated into English:

As newborn babes, alleluia: desire the rational milk without guile, alleluia, alleluia, alleluia.

Low Sunday

[edit]

Another name traditionally given to this day in the English language is Low Sunday. The word "low" may serve to contrast it with the "high" festival of Easter on the preceding Sunday.[9] Or, the word "low" may be a corruption of the Latin word laudes, the first word of a sequence used in the historical Sarum Rite.[10]

Divine Mercy Sunday

[edit]

On April 30, 2000, Pope John Paul II designated the Second Sunday of Easter as Divine Mercy Sunday, based on a petition by St. Faustina Kowalska (1905–1938), who said that Jesus had made this request of the Church in an apparition. In the Roman Missal, the official title of this day is "Second Sunday of Easter; or, Sunday of Divine Mercy" (Latin: Dominica II Paschæ seu de divina Misericordia[11]).

Five years later, Pope John Paul II died the evening before Divine Mercy Sunday, on Saturday, April 2, 2005. His successor, Pope Benedict XVI, beatified him also on a Divine Mercy Sunday, on May 1, 2011.[12]

Celebrations

[edit]

In the Catholic Church, special Divine Mercy celebrations often take place on this day, and the Sacrament of Reconciliation is often administered.[13]

The Italian feast of Our Lady of the Hens[14][15][16][17] and the Chilean Cuasimodo festival[18] are held on this day. Both festivals include Eucharistic processions.

In the Lutheran Churches, the Second Sunday of Easter (or Quasimodogeniti), according to The Lutheran Missal, "recounts the appearance of Our Lord to the apostles in the locked upper room, together with Thomas’ confession."[1]

Dates

The Second Sunday of Easter falls 7 days after Easter, between March 29 and May 2 respectively.

Eastern Christianity

[edit]In Eastern Christianity, this Sunday is called Antipascha, meaning "in place of Easter".[19] It is also called Thomas Sunday due to the Gospel passage read in the Divine Liturgy.[20] Another name for this day in Eastern Christianity is "New Sunday".[21] This Sunday has many hallmarks of a Great Feast, despite not actually being one. For example, no Resurrection texts from the Octoechos are sung, there is a Polyeleos and magnification, the Matins Gospel is read from the Royal Doors and there is no veneration of the Gospel Book, and the Great Prokimenon 'Who is so great a God as our God?' is sung at Vespers on Sunday evening.

In popular culture

[edit]- Quasimodo, the fictional protagonist of Victor Hugo's 1831 French novel Notre Dame de Paris (or The Hunchback of Notre Dame), was, in the novel, found abandoned on the doorsteps of Notre Dame Cathedral on the Sunday after Easter.[22] In the words of the story: "He baptized his adopted child and called him Quasimodo, either because he wanted to indicate thereby the day on which he had found him, or because he wanted the name to typify just how incomplete and half-finished the poor little creature was."[23]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Gramenz, Stefan (6 April 2021). "Eastertide Lections". The Lutheran Missal.

- ^ "Divine Mercy Sunday | USCCB". www.usccb.org. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ "30 April 2000, Canonization of Sr. Mary Faustina Kowalska | John Paul II". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ a b Alston, George Cyprian (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "Sunday of Thomas". Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- ^ Regan, Patrick (2012). Advent to Pentecost. Liturgical Press. pp. 242–243. ISBN 9780814662410.

- ^ Regan, Patrick (2012). Advent to Pentecost. Liturgical Press. pp. 246–249. ISBN 9780814662410.

- ^ a b Missale Romanum (in Latin). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 1962. p. 341.

- ^ "Low Sunday". Chambers Dictionary. Allied Publishers. 1998. p. 954.

- ^ Barbee, C. Frederick; Zahl, Paul F. M., eds. (2006). The Collects of Thomas Cranmer. Eerdmans. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-80281759-4.

- ^ Missale Romanum (in Latin) (3rd revised ed.). Midwest Theological Forum. 2015. p. 314.

- ^ Holdren, Alan (January 14, 2011). "John Paul II's beatification approved for May 1, Divine Mercy Sunday". Catholic News Agency. Archived from the original on November 21, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Matysek Jr., George P. (April 18, 2020). "Divine Mercy Sunday seen as opportunity to receive Christ's mercy "anew"". Crux.

- ^ Swinburne, Henry (1790). Travels in the Two Sicilies. Vol. 3 (2 ed.). London: J. Nichols. p. 166. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ Feldman, Martha (2015). The Castrato. UC Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780520962033. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ Hughes, Jessica (2014-05-13). "Votive chickens". The Votives Project. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ "Pagani". Valle del Sarno. Soprintendenza Beni Archeologici Salerno-Avellino e Benevento. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2021-02-18.

- ^ Chambers, Jane (April 27, 2017). "After Easter, Chileans on horseback take sacraments to homebound". Crux. Archived from the original on January 1, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "Antipascha". Orthodox Church in America. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ Sokolof, Archpriest Dimitrii (2001) [1899]. Manual of the Orthodox Church's Divine Services. Jordanville, New York: Holy Trinity Monastery. p. 109. ISBN 0-884-65067-7.

- ^ "Thomas Sunday (New Sunday)". Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America.

- ^ "Quasimodo Sunday: How the Hunchback got his name". Catholic News Agency. April 28, 2019.

- ^ Hugo, Victor (1996) [1831]. The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. Penguin Books. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-01-4062-222-5.