Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Book of Common Prayer

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Anglicanism |

|---|

|

|

|

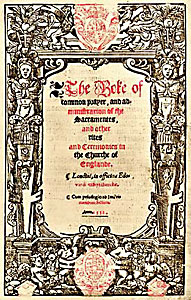

The Book of Common Prayer (BCP) is the title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The first prayer book, published in 1549 in the reign of King Edward VI of England, was a product of the English Reformation following the break with Rome. The 1549 work was the first prayer book to include the complete forms of service for daily and Sunday worship in English. It contains Morning Prayer, Evening Prayer, the Litany, Holy Communion, and occasional services in full: the orders for Baptism, Confirmation, Marriage, "prayers to be said with the sick", and a funeral service. It also sets out in full the "propers" (the parts of the service that vary weekly or daily throughout the Church's Year): the introits, collects, and epistle and gospel readings for the Sunday service of Holy Communion. Old Testament and New Testament readings for daily prayer are specified in tabular format, as are the Psalms and canticles, mostly biblical, to be said or sung between the readings.[1]

The 1549 book was soon succeeded by a 1552 revision that was more Reformed but from the same editorial hand, that of Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury. It was used only for a few months, as after Edward VI's death in 1553, his half-sister Mary I restored Roman Catholic worship. Mary died in 1558 and, in 1559, Elizabeth I's first Parliament authorised the 1559 prayer book, which effectively reintroduced the 1552 book with modifications to make it acceptable to more traditionally minded worshippers and clergy.

In 1604, James I ordered some further changes, the most significant being the addition to the Catechism of a section on the Sacraments; this resulted in the 1604 Book of Common Prayer. Following the tumultuous events surrounding the English Civil War, when the Prayer Book was again abolished, another revision was published as the 1662 prayer book.[2] That edition remains the official prayer book of the Church of England, although throughout the later 20th century, alternative forms that were technically supplements largely displaced the Book of Common Prayer for the main Sunday worship of most English parish churches.

Various permutations of the Book of Common Prayer with local variations are used in churches within and exterior to the Anglican Communion in over 50 countries and over 150 different languages.[3] In many of these churches, the 1662 prayer book remains authoritative even if other books or patterns have replaced it in regular worship.

Traditional English-language Lutheran,[citation needed] Methodist, and Presbyterian prayer books have borrowed from the Book of Common Prayer, and the marriage and burial rites have found their way into those of other denominations and into the English language. Like the King James Version of the Bible and the works of Shakespeare, many words and phrases from the Book of Common Prayer have entered common parlance.

Full title

[edit]The full title of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer is The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, according to the use of the Church of England, Together with the Psalter or Psalms of David, pointed as they are to be Sung or said in churches: And the Form and Manner of Making, ordaining, and Consecrating of Bishops, Priests, and Deacons.[4]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]The forms of parish worship in the late mediaeval church in England, which followed the Latin Roman Rite, varied according to local practice. By far the most common form, or "use", found in Southern England was that of Sarum (Salisbury). There was no single book; the services provided by the Book of Common Prayer were found in the Missal (the Eucharist), the Breviary (daily offices), Manual (the occasional services of baptism, marriage, burial etc.), and Pontifical (services appropriate to a bishop – confirmation, ordination).[5] The chant (plainsong, plainchant) for worship was contained in the Roman Gradual for the Mass, the Antiphonale for the offices, and the Processionale for the litanies.[6] The Book of Common Prayer has never contained prescribed music or chant, but in 1550 John Merbecke produced his Booke of Common Praier noted,[7] which sets much of Mattins, Evensong, Holy Communion and the Burial Office in the Prayer Book to simple plainchant, generally inspired by Sarum Use.[citation needed]

The work of producing a liturgy in English was largely done by Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, starting cautiously in the reign of Henry VIII (1509–1547) and then more radically under his son Edward VI (1547–1553). In his early days, Cranmer was a conservative humanist and an admirer of Erasmus. After 1531, Cranmer's contacts with reformers from continental Europe helped change his outlook.[8] The Exhortation and Litany, the earliest English-language service of the Church of England, was the first overt manifestation of his changing views. It was no mere translation from the Latin, instead making its Protestant character clear by the drastic reduction of the place of saints, compressing what had been the major part into three petitions.[9] Published in 1544, the Exhortation and Litany borrowed greatly from Martin Luther's Litany and Myles Coverdale's New Testament and was the only service that might be considered Protestant to have been finished within Henry VIII's lifetime.[citation needed]

1549 prayer book

[edit]

Only after Henry VIII's death and the accession of Edward VI in 1547 could revision of prayer books proceed faster.[10] Despite conservative opposition, Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity on 21 January 1549, and the newly authorised Book of Common Prayer (BCP) was required to be in use by Whitsunday (Pentecost), 9 June.[10] Cranmer is "credited [with] the overall job of editorship and the overarching structure of the book,"[11] though he borrowed and adapted material from other sources.[12]

The prayer book had provisions for the daily offices (Morning and Evening Prayer), scripture readings for Sundays and holy days, and services for Communion, public baptism, confirmation, matrimony, visitation of the sick, burial, purification of women upon childbirth, and Ash Wednesday. An ordinal for ordination services of bishops, priests, and deacons was added in 1550.[13][14] There was also a calendar and lectionary, which meant a Bible and a Psalter were the only other books a priest required.[14]

The BCP represented a "major theological shift" in England towards Protestantism.[14] Cranmer's doctrinal concerns can be seen in the systematic amendment of source material to remove any idea that merit contributes to salvation.[15] The doctrines of justification by faith and predestination are central to Cranmer's theology. These doctrines are implicit throughout the prayer book and had important implications for his understanding of the sacraments. Cranmer believed that someone who was not one of God's elect received only the outward form of the sacrament (washing in baptism or eating bread in Communion), not actual grace, with only the elect receiving the sacramental sign and the grace. Cranmer held the position that faith, a gift given only to the elect, united the outward sign of sacrament and its inward grace, with only the unity of the two making the sacrament effective. This position was in agreement with the Reformed churches but in opposition to Roman Catholic and Lutheran views.[16]

As a compromise with conservatives, the word Mass was kept, with the service titled "The Supper of the Lord and the Holy Communion, commonly called the Mass".[17] The service also preserved much of the Mass's mediaeval structure – stone altars remained, the clergy wore traditional vestments, much of the service was sung, and the priest was instructed to put the communion wafer into communicants' mouths instead of in their hands.[18][19] Nevertheless, the first BCP was a "radical" departure from traditional worship in that it "eliminated almost everything that had till then been central to lay Eucharistic piety".[20]

A priority for Protestants was to replace the Roman Catholic teaching that the Mass was a sacrifice to God ("the very same sacrifice as that of the cross") with the Protestant teaching that it was a service of thanksgiving and spiritual communion with Christ.[21][22] Cranmer's intention was to suppress Catholic notions of sacrifice and transubstantiation in the Mass.[17] To stress this, there was no elevation of the consecrated bread and wine, and eucharistic adoration was prohibited. The elevation had been the central moment of the mediaeval Mass, attached as it was to the idea of real presence.[23][24] Cranmer's eucharistic theology was close to the Calvinist spiritual presence view, and can be described as Receptionism and Virtualism: the real presence of Jesus by the power of the Holy Spirit.[25][26] The words of administration in the 1549 rite are deliberately ambiguous; they can be understood as identifying the bread with the body of Christ or (following Cranmer's theology) as a prayer that the communicant might spiritually receive the body of Christ by faith.[27]

Many of the other services were little changed. Cranmer based his baptism service on Martin Luther's service, a simplification of the long and complex mediaeval rite. Like communion, the baptism service maintained a traditional form.[28] The confirmation and marriage services followed the Sarum rite.[29] There are also remnants of prayer for the dead and the Requiem Mass, such as the provision for celebrating holy communion at a funeral.[30] Cranmer's work of simplification and revision was also applied to the Daily Offices, which were reduced to Morning and Evening Prayer. Cranmer hoped these would also serve as a daily form of prayer to be used by the laity, thus replacing both the late mediaeval lay observation of the Latin Hours of the Virgin and its English-language equivalent primers.[31]

1552 prayer book

[edit]

From the outset, the 1549 book was intended only as a temporary expedient, as German reformer Bucer was assured on meeting Cranmer for the first time in April 1549: "concessions ... made both as a respect for antiquity and to the infirmity of the present age", as he wrote.[32] According to historian Christopher Haigh, the 1552 prayer book "broke decisively with the past".[33] The services for baptism, confirmation, communion and burial are rewritten, and ceremonies hated by Protestants were removed. Unlike the 1549 version, the 1552 prayer book removed many traditional sacramentals and observances that reflected belief in the blessing and exorcism of people and objects. In the baptism service, infants no longer receive minor exorcism.[34] Anointing is no longer included in the services for baptism, ordination and visitation of the sick.[34] These ceremonies are altered to emphasise the importance of faith, rather than trusting in rituals or objects.[35]

Many of the traditional elements of the communion service were removed in the 1552 version.[36] The name of the service was changed to "The Order for the Administration of the Lord's Supper or Holy Communion", removing the word Mass. Stone altars were replaced with communion tables positioned in the chancel or nave, with the priest standing on the north side. The priest is to wear the surplice instead of traditional Mass vestments.[37] The service appears to promote a spiritual presence view of the Eucharist, meaning that Christ is spiritually but not corporally present.[38]

There was controversy over how people should receive communion: kneeling or seated. John Knox protested against kneeling.[38] Ultimately, it was decided that communicants should continue to kneel, but the Privy Council ordered that the Black Rubric be added to the prayer book to clarify the purpose of kneeling. The rubric denied "any real and essential presence ... of Christ's natural flesh and blood" in the Eucharist and was the clearest statement of eucharistic theology in the prayer book.[39] The 1552 service removed any reference to the "body of Christ" in the words of administration to reinforce the teaching that Christ's presence in the Eucharist was a spiritual presence and, in the words of historian Peter Marshall, "limited to the subjective experience of the communicant".[35] Instead of communion wafers, the prayer book instructs that ordinary bread is to be used "to take away the superstition which any person hath, or might have".[35] To further emphasise there is no holiness in the bread and wine, any leftovers are to be taken home by the curate for ordinary consumption. This prevented eucharistic adoration of the reserved sacrament above the high altar.[40][37][35]

The burial service was removed from the church. It was to now take place at the graveside.[41] In 1549, there had been provision for a Requiem (not so called) and prayers of commendation and committal, the first addressed to the deceased. All that remained was a single reference to the deceased, giving thanks for their delivery from 'the myseryes of this sinneful world.' This new Order for the Burial of the Dead is a drastically stripped-down memorial service designed to undermine definitively the whole complex of traditional Catholic beliefs about Purgatory and intercessory prayer for the dead.[42][43]

The Orders of Morning and Evening Prayer are extended by the inclusion of a penitential section at the beginning including a corporate confession of sin and a general absolution, although the text is printed only in Morning Prayer with rubrical directions to use it in the evening as well. The general pattern of Bible reading in the 1549 edition is retained (as it was in 1559) except that distinct Old and New Testament readings are now specified for Morning and Evening Prayer on certain feast days. A revised English Primer was published in 1553, adapting the Offices, Morning and Evening Prayer, and other prayers for lay domestic piety.[44]

The 1552 book was used only for a short period, as Edward VI died in the summer of 1553 and, as soon as she could do so, Mary I restored union with Rome. The Latin Mass was reestablished, with altars, roods, and statues of saints reinstated in an attempt to restore the English Church to its Roman affiliation. Cranmer was punished for his work in the English Reformation by being burned at the stake on 21 March 1556. Nevertheless, the 1552 book survived. After Mary's death in 1558, it became the primary source for the Elizabethan Book of Common Prayer, with only subtle, if significant, changes.

Hundreds of English Protestants fled into exile, establishing an English church in Frankfurt am Main. A bitter and very public dispute ensued between those, such as Edmund Grindal and Richard Cox, who wished to preserve in exile the exact form of worship of the 1552 Prayer Book, and those, such as the minister of the congregation John Knox, who saw that book as still partially tainted by compromise. In 1555, the civil authorities expelled Knox and his supporters to Geneva, where they adopted a new prayer book, The Form of Prayers, which principally derived from Calvin's French-language La Forme des Prières.[45] Consequently, when the accession of Elizabeth I reasserted the dominance of the Reformed Church of England, a significant body of more Protestant believers remained who were nevertheless hostile to the Book of Common Prayer. Knox took The Form of Prayers with him to Scotland, where it formed the basis of the Scottish Book of Common Order.

1559 prayer book

[edit]

Under Elizabeth I, a more permanent enforcement of the reformed Church of England was undertaken and the 1552 book was republished, scarcely altered, in 1559.[46] The Prayer Book of 1552 "was a masterpiece of theological engineering."[47] The doctrines in the Prayer Book and the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion as set forth in 1559 would set the tone of Anglicanism, which preferred to steer a via media ("middle way") between Lutheranism and Calvinism. The conservative nature of these changes underlines the fact that Reformed principles were by no means universally popular – a fact that the Queen recognised. Her revived Act of Supremacy, giving her the ambiguous title of supreme governor, passed without difficulty, but the Act of Uniformity 1558, giving statutory force to the Prayer Book, passed through the House of Lords by only three votes in 1559.[48] It made constitutional history in being imposed by the laity alone, as all the bishops, except those imprisoned by the Queen and unable to attend, voted against it.[49] Convocation had made its position clear by affirming the traditional doctrine of the Eucharist, the authority of the Pope, and the reservation by divine law to clergy "of handling and defining concerning the things belonging to faith, sacraments, and discipline ecclesiastical."[50] After these innovations and reversals, the new forms of Anglican worship took several decades to gain acceptance, but by the end of her reign in 1603, 70–75% of the English population were on board.

The alterations, though minor, were, however, to cast a long shadow over the development of the Church of England. It would be a long road back for the Church, with no clear indication that it would retreat from the 1559 Settlement except for minor official changes. In one of the first moves to undo Cranmer's liturgy, the Queen insisted that the Words of Administration of Communion from the 1549 Book be placed before the Words of Administration in the 1552 Book, thereby re-opening the issue of the Real Presence. At the administration of the Holy Communion, the words from the 1549 book, "the Body of our Lord Jesus Christ ...," were combined with the words of Edward VI's second Prayer Book of 1552, "Take, eat in remembrance ...," "suggesting on the one hand a real presence to those who wished to find it and on the other, the communion as memorial only,"[47] i.e. an objective presence and subjective reception. The 1559 Prayer Book, however, retained the truncated Prayer of Consecration of the Communion elements, which omitted any notion of objective sacrifice. It was preceded by the Proper Preface and Prayer of Humble Access (placed there to remove any implication that the Communion was a sacrifice to God). The Prayer of Consecration was followed by Communion, the Lord's Prayer, and a Prayer of Thanksgiving or an optional Prayer of Oblation whose first line included a petition that God would "...accepte this our Sacrifice of prayse and thankes geuing...". The latter prayer was removed (a longer version followed the Words of the Institution in the 1549 Rite) "to avoid any suggestion of the sacrifice of the Mass." The Marian Bishop Scot opposed the 1552 Book "on the grounds it never makes any connection between the bread and the Body of Christ. Untrue though [his accusation] was, the restoration of the 1549 Words of Distribution emphasized its falsity."[51]

However, beginning in the 17th century, some prominent Anglican theologians tried to cast a more traditional Catholic interpretation onto the text as a Commemorative Sacrifice and Heavenly Offering even though the words of the Rite did not support such interpretations. Cranmer, a good liturgist, was aware that the Eucharist from the mid-second century on had been regarded as the Church's offering to God, but he removed the sacrificial language anyway, whether under pressure or conviction.[52] It was not until the Anglican Oxford Movement of the mid-19th century and later 20th-century revisions that the Church of England would attempt to deal with the eucharistic doctrines of Cranmer by bringing the Church back to "pre-Reformation doctrine."[53] In the meantime, the Scottish and American Prayer Books not only reverted to the 1549 text, but even to the older Roman and Eastern Orthodox pattern by adding the Oblation and an Epiclesis – i.e. the congregation offers itself in union with Christ at the Consecration and receives Him in Communion – while retaining the Calvinist notions of "may be for us" rather than "become" and the emphasis on "bless and sanctify us" (the tension between the Catholic stress on objective Real Presence and Protestant subjective worthiness of the communicant). However, these Rites asserted a kind of Virtualism in regard to the Real Presence while making the Eucharist a material sacrifice because of the oblation,[54] and the retention of "may be for us the Body and Blood of thy Savior" rather than "become" thus eschewing any suggestion of a change in the natural substance of bread and wine.

Another move, the "Ornaments Rubric", related to what clergy were to wear while conducting services. Instead of the banning of all vestments except the rochet for bishops and the surplice for parish clergy, it permitted "such ornaments ... as were in use ... in the second year of King Edward VI." This allowed substantial leeway for more traditionalist clergy to retain the vestments which they felt were appropriate to liturgical celebration, namely Mass vestments such as albs, chasubles, dalmatics, copes, stoles, maniples, etc. (at least until the Queen gave further instructions, as per the text of the Act of Uniformity of 1559). The rubric also stated that the Communion service should be conducted in the 'accustomed place,' namely a Table against the wall with the priest facing it. The rubric was placed at the section regarding Morning and Evening Prayer in this Prayer Book and in the 1604 and 1662 Books. It was to be the basis of claims in the 19th century that vestments such as chasubles, albs and stoles were canonically permitted.

The instruction to the congregation to kneel when receiving communion was retained, but the Black Rubric (#29 in the Forty-Two Articles of Faith, which were later reduced to 39) which denied any "real and essential presence" of Christ's flesh and blood, was removed to "conciliate traditionalists" and aligned with the Queen's sensibilities.[55] The removal of the Black Rubric complements the double set of Words of Administration at the time of communion and permits an action – kneeling to receive – which people were used to doing. Therefore, nothing at all was stated in the Prayer Book about a theory of the Presence or forbidding reverence or adoration of Christ via the bread and wine in the Sacrament. On this issue, however, the Prayer Book was at odds with the repudiation of transubstantiation and the forbidden carrying about of the Blessed Sacrament in the Thirty-Nine Articles. As long as one did not subscribe publicly to or assert the latter, one was left to hold whatever opinion one wanted on the former. The Queen herself was famous for saying she was not interested in "looking in the windows of men's souls."

Among Cranmer's innovations, retained in the new Prayer Book, was the requirement of weekly Holy Communion services. In practice, as before the English Reformation, many received communion rarely, as little as once a year in some cases; George Herbert estimated it at no more than six times per year.[56] Practice, however, varied from place to place. Very high attendance at festivals was the order of the day in many parishes and in some, regular communion was very popular; in other places families stayed away or sent "a servant to be the liturgical representative of their household."[57][58] Few parish clergy were initially licensed by the bishops to preach; in the absence of a licensed preacher, Sunday services were required to be accompanied by reading one of the homilies written by Cranmer.[59] George Herbert was, however, not alone in his enthusiasm for preaching, which he regarded as one of the prime functions of a parish priest.[60] Music was much simplified, and a radical distinction developed between, on the one hand, parish worship, where only the metrical psalms of Sternhold and Hopkins might be sung, and, on the other hand, worship in churches with organs and surviving choral foundations, where the music of John Marbeck and others was developed into a rich choral tradition.[61][62] The whole act of parish worship might take well over two hours, and accordingly, churches were equipped with pews in which households could sit together (whereas in the medieval church, men and women had worshipped separately). Diarmaid MacCulloch describes the new act of worship as "a morning marathon of prayer, scripture reading, and praise, consisting of mattins, litany, and ante-communion, preferably as the matrix for a sermon to proclaim the message of scripture anew week by week."[58]

Many ordinary churchgoers – that is, those who could afford one, as it was expensive – would own a copy of the Prayer Book. Judith Maltby cites a story of parishioners at Flixton in Suffolk who brought their own Prayer Books to church in order to shame their vicar into conforming with it. They eventually ousted him.[63] Between 1549 and 1642, roughly 290 editions of the Prayer Book were produced.[64] Before the end of the English Civil War (1642–1651) and the introduction of the 1662 prayer book, something like a half a million prayer books are estimated to have been in circulation.[64]

The 1559 prayer book was also translated into other languages within the English sphere of influence. A translation into Latin was made in the form of Walter Haddon's Liber Precum Publicarum of 1560. Intended for use in the worship of the collegiate chapels of Oxford, Cambridge, Eton, and Winchester, it was resisted by some Protestants.[65] The Welsh edition of the Book of Common Prayer for use in the Church in Wales was published in 1567. It was translated by William Salesbury assisted by Richard Davies.[66]

Changes in 1604

[edit]On Elizabeth's death in 1603, the 1559 book, substantially that of 1552 which had been regarded as offensive by some, such as Bishop Stephen Gardiner, as being a break with the tradition of the Western Church, had come to be regarded in some quarters as unduly Catholic. On his accession and following the so-called "Millenary Petition", James I called the Hampton Court Conference in 1604 – the same meeting of bishops and Puritan divines that initiated the Authorized King James Version of the Bible. This was in effect a series of two conferences: (i) between James and the bishops; (ii) between James and the Puritans on the following day. The Puritans raised four areas of concern: purity of doctrine; the means of maintaining it; church government; and the Book of Common Prayer. Confirmation, the cross in baptism, private baptism, the use of the surplice, kneeling for communion, reading the Apocrypha; and subscription to the BCP and Articles were all touched on. On the third day, after James had received a report back from the bishops and made final modifications, he announced his decisions to the Puritans and bishops.[67]

The business of making the changes was then entrusted to a small committee of bishops and the Privy Council and, apart from tidying up details, this committee introduced into Morning and Evening Prayer a prayer for the royal family; added several thanksgivings to the Occasional Prayers at the end of the Litany; altered the rubrics of Private Baptism limiting it to the minister of the parish, or some other lawful minister, but still allowing it in private houses (the Puritans had wanted it only in the church); and added to the Catechism the section on the sacraments. The changes were put into effect by means of an explanation issued by James in the exercise of his prerogative under the terms of the 1559 Act of Uniformity and Act of Supremacy.[68]

The accession of Charles I (1625–1649) brought about a complete change in the religious scene in that the new king used his supremacy over the established church "to promote his own idiosyncratic style of sacramental Kingship" which was "a very weird aberration from the first hundred years of the early reformed Church of England". He questioned "the populist and parliamentary basis of the Reformation Church" and unsettled to a great extent "the consensual accommodation of Anglicanism".[69] These changes, along with a new edition of the Book of Common Prayer, led to the Bishops' Wars and later to the English Civil War.

With the defeat of Charles I (1625–1649) in the Civil War, the Puritan pressure, exercised through a much-changed Parliament, had increased. Puritan-inspired petitions for the removal of the prayer book and episcopacy "root and branch" resulted in local disquiet in many places and, eventually, the production of locally organised counter petitions. The parliamentary government had its way but it became clear that the division was not between Catholics and Protestants, but between Puritans and those who valued the Elizabethan settlement.[64] The 1604 book was finally outlawed by Parliament in 1645 to be replaced by the Directory of Public Worship, which was more a set of instructions than a prayer book. How widely the Directory was used is not certain; there is some evidence of its having been purchased, in churchwardens' accounts, but not widely. The Prayer Book certainly was used clandestinely in some places, not least because the Directory made no provision at all for burial services. Following the execution of Charles I in 1649 and the establishment of the Commonwealth under Lord Protector Cromwell, the Prayer Book was not reinstated until shortly after the restoration of the monarchy to England.

John Evelyn records, in Diary, receiving communion according to the 1604 Prayer Book rite:

Christmas Day 1657. I went to London with my wife to celebrate Christmas Day. ... Sermon ended, as [the minister] was giving us the holy sacrament, the chapel was surrounded with soldiers, and all the communicants and assembly surprised and kept prisoners by them, some in the house, others carried away. ... These wretched miscreants held their muskets against us as we came up to receive the sacred elements, as if they would have shot us at the altar.

Changes made in Scotland

[edit]

In 1557, the Scots Protestant lords had adopted the English Prayer Book of 1552, for reformed worship in Scotland. However, when John Knox returned to Scotland in 1559, he continued to use the Form of Prayer he had created for the English exiles in Geneva and, in 1564, this supplanted the Book of Common Prayer under the title of the Book of Common Order.

Following the accession of King James VI of Scotland to the throne of England his son, King Charles I, with the assistance of Archbishop Laud, sought to impose the prayer book on Scotland.[70] The 1637 prayer book was not, however, the 1559 book but one much closer to that of 1549, the first book of Edward VI. First used in 1637, it was never accepted, having been violently rejected by the Scots. During one reading of the book at the Holy Communion in St Giles' Cathedral, the Bishop of Brechin was forced to protect himself while reading from the book by pointing loaded pistols at the congregation.[71] Following the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (including the English Civil War), the Church of Scotland was re-established on a presbyterian basis but by the Act of Comprehension 1690, the rump of Episcopalians were allowed to hold onto their benefices. For liturgy, they looked to Laud's book and in 1724 the first of the "wee bookies" was published, containing, for the sake of economy, the central part of the Communion liturgy beginning with the offertory.[72]

Between then and 1764, when a more formal revised version was published, a number of things happened which were to separate the Scottish Episcopal liturgy more firmly from either the English books of 1549 or 1559. First, informal changes were made to the order of the various parts of the service and inserting words indicating a sacrificial intent to the Eucharist clearly evident in the words, "we thy humble servants do celebrate and make before thy Divine Majesty with these thy holy gifts which we now OFFER unto thee, the memorial thy Son has commandeth us to make;" secondly, as a result of Bishop Rattray's researches into the liturgies of St James and St Clement, published in 1744, the form of the invocation was changed. These changes were incorporated into the 1764 book which was to be the liturgy of the Scottish Episcopal Church (until 1911 when it was revised) but it was to influence the liturgy of the Episcopal Church in the United States. A new revision was finished in 1929, the Scottish Prayer Book 1929, and several alternative orders of the Communion service and other services have been prepared since then.

1662 prayer book

[edit]

The 1662 Prayer Book was printed two years after the restoration of the monarchy, following the Savoy Conference between representative Presbyterians and twelve bishops which was convened by royal warrant to "advise upon and review the Book of Common Prayer".[73] Attempts by the Presbyterians, led by Richard Baxter, to gain approval for an alternative service book failed. Their major objections (exceptions) were: firstly, that it was improper for lay people to take any vocal part in prayer (as in the Litany or Lord's Prayer), other than to say "amen"; secondly, that no set prayer should exclude the option of an extempore alternative from the minister; thirdly, that the minister should have the option to omit part of the set liturgy at his discretion; fourthly, that short collects should be replaced by longer prayers and exhortations; and fifthly, that all surviving "Catholic" ceremonial should be removed.[74] The intent behind these suggested changes was to achieve a greater correspondence between liturgy and Scripture. The bishops gave a frosty reply. They declared that liturgy could not be circumscribed by Scripture, but rightfully included those matters which were "generally received in the Catholic church." They rejected extempore prayer as apt to be filled with "idle, impertinent, ridiculous, sometimes seditious, impious and blasphemous expressions." The notion that the Prayer Book was defective because it dealt in generalisations brought the crisp response that such expressions were "the perfection of the liturgy".[75]

The Savoy Conference ended in disagreement late in July 1661, but the initiative in prayer book revision had already passed to the Convocations and from there to Parliament.[76] The Convocations made some 600 changes, mostly of details, which were "far from partisan or extreme".[77] However, Edwards states that more of the changes suggested by high Anglicans were implemented (though by no means all)[78] and Spurr comments that (except in the case of the Ordinal) the suggestions of the "Laudians" (Cosin and Matthew Wren) were not taken up possibly due to the influence of moderates such as Sanderson and Reynolds. For example, the inclusion in the intercessions of the Communion rite of prayer for the dead was proposed and rejected. The introduction of "Let us pray for the whole state of Christ's Church militant here in earth" remained unaltered and only a thanksgiving for those "departed this life in thy faith and fear" was inserted to introduce the petition that the congregation might be "given grace so to follow their good examples that with them we may be partakers of thy heavenly kingdom". Griffith Thomas commented that the retention of the words "militant here in earth" defines the scope of this petition: we pray for ourselves, we thank God for them, and adduces collateral evidence to this end.[79] Secondly, an attempt was made to restore the Offertory. This was achieved by the insertion of the words "and oblations" into the prayer for the Church and the revision of the rubric so as to require the monetary offerings to be brought to the table (instead of being put in the poor box) and the bread and wine placed upon the table. Previously it had not been clear when and how bread and wine got onto the altar. The so-called "manual acts", whereby the priest took the bread and the cup during the prayer of consecration, which had been deleted in 1552, were restored; and an "amen" was inserted after the words of institution and before communion, hence separating the connections between consecration and communion which Cranmer had tried to make. After communion, the unused but consecrated bread and wine were to be reverently consumed in church rather than being taken away for the priest's own use. By such subtle means were Cranmer's purposes further confused, leaving it for generations to argue over the precise theology of the rite. One change made that constituted a concession to the Presbyterian Exceptions, was the updating and re-insertion of the so-called "Black Rubric", which had been removed in 1559. This now declared that kneeling in order to receive communion did not imply adoration of the species of the Eucharist nor "to any Corporal Presence of Christ's natural Flesh and Blood" – which, according to the rubric, were in heaven, not here.

While intended to create unity, the division established under the Commonwealth and the licence given by the Directory for Public Worship were not easily passed by. Unable to accept the new book, 936 ministers were deprived during the Great Ejection.[80][a] The actual language of the 1662 revision was little changed from that of Cranmer. With two exceptions, some words and phrases which had become archaic were modernised; secondly, the readings for the epistle and gospel at Holy Communion, which had been set out in full since 1549, were now set to the text of the 1611 Authorized King James Version of the Bible. The Psalter, which had not been printed in the 1549, 1552 or 1559 books – was in 1662 provided in Miles Coverdale's translation from the Great Bible of 1538.

It was this edition which was to be the official Book of Common Prayer during the growth of the British Empire and, as a result, has been a great influence on the prayer books of Anglican churches worldwide, liturgies of other denominations in English, and of the English people and language as a whole.

Further attempts at revision

[edit]1662–1832

[edit]

Between 1662 and the 19th century, further attempts to revise the Book in England stalled. On the death of Charles II, his brother James, a Roman Catholic, became James II. James wished to achieve toleration for those of his own Roman Catholic faith, whose practices were still banned. This, however, drew the Presbyterians closer to the Church of England in their common desire to resist 'popery'; talk of reconciliation and liturgical compromise was thus in the air. But with the flight of James in 1688 and the arrival of the Calvinist William of Orange the position of the parties changed. The Presbyterians could achieve toleration of their practices without such a right being given to Roman Catholics and without, therefore, their having to submit to the Church of England, even with a liturgy more acceptable to them. They were now in a much stronger position to demand changes that were ever more radical. John Tillotson, Dean of Canterbury pressed the king to set up a commission to produce such a revision.[81] The so-called Liturgy of Comprehension of 1689, which was the result, conceded two thirds of the Presbyterian demands of 1661; but, when it came to convocation the members, now more fearful of William's perceived agenda, did not even discuss it and its contents were, for a long time, not even accessible.[82] This work, however, did go on to influence the prayer books of many British colonies.

1833–1906

[edit]

By the 19th century, pressures to revise the 1662 book were increasing. Adherents of the Oxford Movement, begun in 1833, raised questions about the relationship of the Church of England to the apostolic church and thus about its forms of worship. Known as Tractarians after their production of Tracts for the Times on theological issues, they advanced the case for the Church of England being essentially a part of the "Western Church", of which the Roman Catholic Church was the chief representative. The illegal use of elements of the Roman rite, the use of candles, vestments and incense – practices collectively known as Ritualism – had become widespread and led to the establishment of a new system of discipline, intending to bring the "Romanisers" into conformity, through the Public Worship Regulation Act 1874.[83] The Act had no effect on illegal practices: five clergy were imprisoned for contempt of court and after the trial of the much loved Bishop Edward King of Lincoln, it became clear that some revision of the liturgy had to be embarked upon.[84]

One branch of the Ritualism movement argued that both "Romanisers" and their Evangelical opponents, by imitating, respectively, the Church of Rome and Reformed churches, transgressed the Ornaments Rubric of 1559 ("... that such Ornaments of the Church, and of the Ministers thereof, at all Times of their Ministration, shall be retained, and be in use, as were in this Church of England, by the Authority of Parliament, in the Second Year of the Reign of King Edward the Sixth"). These adherents of ritualism, among whom were Percy Dearmer and others, claimed that the Ornaments Rubric prescribed the ritual usages of the Sarum Rite with the exception of a few minor things already abolished by the early reformation.

Following a royal commission report in 1906, work began on a new prayer book. It took twenty years to complete, prolonged partly due to the demands of the First World War and partly in the light of the 1920 constitution of the Church Assembly, which "perhaps not unnaturally wished to do the work all over again for itself".[85]

1906–2000

[edit]In 1927, the work on a new version of the prayer book reached its final form. In order to reduce conflict with traditionalists, it was decided that the form of service to be used would be determined by each congregation. With these open guidelines, the book was granted approval by the Church of England Convocations and Church Assembly in July 1927. However, it was defeated by the House of Commons in 1928.

The effect of the failure of the 1928 book was salutary: no further attempts were made to revise the Book of Common Prayer. Instead a different process, that of producing an alternative book, led to the publication of Series 1, 2 and 3 in the 1960s, the 1980 Alternative Service Book and subsequently to the 2000 Common Worship series of books. Both differ substantially from the Book of Common Prayer, though the latter includes in the Order Two form of the Holy Communion a very slight revision of the prayer book service, largely along the lines proposed for the 1928 Prayer Book. Order One follows the pattern of the modern Liturgical Movement.

In the Anglican Communion

[edit]

With British colonial expansion from the 17th century onwards, Anglicanism spread across the globe. The new Anglican churches used and revised the use of the Book of Common Prayer, until they, like the English church, produced prayer books which took into account the developments in liturgical study and practice in the 19th and 20th centuries which come under the general heading of the Liturgical Movement.

Africa

[edit]In South Africa a Book of Common Prayer was "Set Forth by Authority for Use in the Church of the Province of South Africa" in 1954. The 1954 prayer book is still in use in some churches in southern Africa; however, it has been largely replaced by An Anglican Prayerbook 1989 and versions of that translated to other languages in use in southern Africa.

Asia

[edit]Bangladesh

[edit]

The Book of Common Prayer of the Church of Bangladesh, translated literally as "prayer book" (Bengali: প্রার্থনা বই) was approved by synod in 1997.[86] The book contains prayers translated from the traditional Book of Common Prayer as well as those from the Church of North India and the CWM's Prayer Letter, along with original compositions by the Church of Bangladesh.

China

[edit]The Book of Common Prayer is translated literally as (公禱書) in Chinese (Mandarin: Gōng dǎo shū; Cantonese: Gūng tóu syū). The former dioceses in the now defunct Chung Hua Sheng Kung Hui had their own Book of Common Prayer. The General Synod and the College of Bishops of Chung Hwa Sheng Kung Hui planned to publish a unified version for the use of all Anglican churches in China in 1949, which was the 400th anniversary of the first publishing of the Book of Common Prayer. After the communists took over mainland China, the Diocese of Hong Kong and Macao became independent of the Chung Hua Sheng Kung Hui, and continued to use the edition issued in Shanghai in 1938 with a revision in 1959. This edition, also called the "Black-Cover Book of Common Prayer" (黑皮公禱書) for its cover, still remains in use after the establishment of the Hong Kong Sheng Kung Hui (Anglican province in Hong Kong). The language style of "Black-Cover Book of Common Prayer" is closer to Classical Chinese than contemporary Chinese.

India

[edit]The Church of South India was the first modern Episcopal uniting church, consisting as it did, from its foundation in 1947, at the time of Indian independence, of Anglicans, Methodists, Congregationalists, Presbyterians and Reformed Christians. Its liturgy, from the first, combined the free use of Cranmer's language with an adherence to the principles of congregational participation and the centrality of the Eucharist, much in line with the Liturgical Movement. Because it was a minority church of widely differing traditions in a non-Christian culture (except in Kerala, where Christianity has a long history), practice varied wildly.

Japan

[edit]The BCP is called "Kitōsho" (Japanese: 祈祷書) in Japanese. The initial effort to compile such a book in Japanese goes back to 1859, when the missionary societies of the Church of England and of the Episcopal Church of the United States started their work in Japan, later joined by the Anglican Church of Canada in 1888. In 1879, the Seikōkai Tō Bun (聖公会祷文, Anglican Prayer Texts) were prepared in Japanese[87][88] As the Anglican Church in Japan was established in 1887, the Romanised Nippon Seikōkai Kitō Bun (Japanese: 日本聖公会祈祷文) were compiled in 1879.[89] There was a major revision of these texts and the first Kitōsho was born in 1895, which had the Eucharistic part in both English and American traditions.[90] There were further revisions, and the Kitōsho published in 1939 was the last revision that was done before World War II, still using the Historical kana orthography.[91]

After the end of the War, the Kitōsho of 1959 became available, using post-war Japanese orthography, but still in traditional classical Japanese language and vertical writing. In the fifty years after World War II, there were several efforts to translate the Bible into modern colloquial Japanese, the most recent of which was the publication in 1990 of the Japanese New Interconfessional Translation Bible. The Kitōsho using the colloquial Japanese language and horizontal writing was published in the same year. It also used the Revised Common Lectionary. This latest Kitōsho since went through several minor revisions, such as employing the Lord's Prayer in Japanese common with the Catholic Church (共通口語訳「主の祈り」) in 2000.

Korea

[edit]In 1965, the Anglican Church of Korea first published a translation of the 1662 BCP into Korean and called it gong-dong-gi-do-mun (공동기도문) meaning "common prayers". In 1994, the prayers announced "allowed" by the 1982 Bishops Council of the Anglican Church of Korea was published in a second version of the Book of Common Prayers In 2004, the National Anglican Council published the third and the current Book of Common Prayers known as "seong-gong-hwe gi-do-seo (성공회 기도서)" or the "Anglican Prayers", including the Calendar of the Church Year, Daily Offices, Collects, Proper Liturgies for Special Days, Baptism, Holy Eucharist, Pastoral Offices, Episcopal Services, Lectionary, Psalms and all of the other events the Anglican Church of Korea celebrates.

The Diction of the books has changed from the 1965 version to the 2004 version. For example, the word "God" has changed from classical Chinese term "Cheon-ju (천주)" to native Korean word "ha-neu-nim (하느님)," in accordance with the Public Christian translation, and as used in 1977 Common Translation Bible (gong-dong beon-yeok-seong-seo, 공동번역성서) that the Anglican Church of Korea currently uses.

Philippines

[edit]

As the Philippines is connected to the worldwide Anglican Communion through the Episcopal Church in the Philippines, the main edition of the Book of Common Prayer in use throughout the islands is the same as that of the United States.

Aside from the American version and the newly published Philippine Book of Common Prayer, Filipino-Chinese congregants of Saint Stephen's Pro-Cathedral in the Diocese of the Central Philippines uses the English-Chinese Diglot Book of Common Prayer, published by the Episcopal Church of Southeast Asia.

The ECP has since published its own Book of Common Prayer upon gaining full autonomy on 1 May 1990. This version is notable for the inclusion of the Misa de Gallo, a popular Christmastide devotion amongst Filipinos that is of Catholic origin.

Europe

[edit]Ireland

[edit]

The first printed book in Ireland was in English, the Book of Common Prayer.[92]

William Bedell had undertaken an Irish translation of the Book of Common Prayer in 1606. An Irish translation of the revised prayer book of 1662 was effected by John Richardson (1664–1747) and published in 1712 as Leabhar na nornaightheadh ccomhchoitchionn. "Until the 1960s, the Book of Common Prayer, derived from 1662 with only mild tinkering, was quite simply the worship of the church of Ireland."[93] The 1712 edition had parallel columns in English and Irish languages.[94]

After its independence and disestablishment in 1871, the Church of Ireland developed its own prayer book which was published in 1878.[95][96] It has been revised several times, and the present edition has been used since 2004.[97]

Isle of Man

[edit]The first Manx translation of the Book of Common Prayer was made by John Phillips (Bishop of Sodor and Man) in 1610. A more successful "New Version" by his successor Mark Hiddesley was in use until 1824 when English liturgy became universal on the island.[98]

Portugal

[edit]The Lusitanian Catholic Apostolic Evangelical Church formed in 1880. A Portuguese language Prayer Book is the basis of the Church's liturgy. In the early days of the church, a translation into Portuguese from 1849 of the 1662 edition of the Book of Common Prayer was used. In 1884 the church published its own prayer book based on the Anglican, Roman and Mozarabic liturgies. The intent was to emulate the customs of the primitive apostolic church.[99] Newer editions of their prayer book are available in Portuguese and with an English translation.[100]

Spain

[edit]

The Spanish Reformed Episcopal Church (Spanish: Iglesia Española Reformada Episcopal, IERE) is the church of the Anglican Communion in Spain. It was founded in 1880 and since 1980 has been an extra-provincial church under the metropolitan authority of the Archbishop of Canterbury. Previous to its organisation, there were several translations of the Book of Common Prayer into Spanish in 1623[101] and in 1707.[102]

In 1881 the church combined a Spanish translation of the 1662 edition of the Book of Common Prayer with the Mozarabic Rite liturgy, which had recently been translated. This is apparently the first time the Spanish speaking Anglicans inserted their own "historic, national tradition of liturgical worship within an Anglican prayer book."[103] A second edition was released in 1889, and a revision in 1975. This attempt combined the Anglican structure of worship with indigenous prayer traditions.[104]

Wales

[edit]

An Act of Parliament passed in 1563, entitled "An Act for the Translating of the Bible and the Divine Service into the Welsh Tongue", ordered that both the Old and New Testament be translated into Welsh, alongside the Book of Common Prayer. This translation – completed by the then bishop of St David's, Richard Davies, and the scholar William Salesbury – was published in 1567[105] as Y Llyfr Gweddi Gyffredin. A further revision, based on the 1662 English revision, was published in 1664.[98]

The Church in Wales began a revision of the book of Common Prayer in the 1950s. Various sections of authorised material were published throughout the 1950s and 1960s; however, common usage of these revised versions only began with the introduction of a revised order for the Holy Eucharist. Revision continued throughout the 1960s and 1970s, with definitive orders being confirmed throughout the 70s for most orders. A finished, fully revised Book of Common Prayer for use in the Church in Wales was authorised in 1984, written in traditional English, after a suggestion for a modern language Eucharist received a lukewarm reception.[citation needed]

In the 1990s, new initiation services were authorised, followed by alternative orders for morning and evening prayer in 1994, alongside an alternative order for the Holy Eucharist, also in 1994. Revisions of various orders in the Book of Common Prayer continued throughout the 2000s and into the 2010s.[citation needed]

Oceania

[edit]Aotearoa, New Zealand, Polynesia

[edit]As for other parts of the British Empire, the 1662 Book of Common Prayer was initially the standard of worship for Anglicans in New Zealand. The 1662 Book was first translated into Māori in 1830, and has gone through several translations and a number of different editions since then. The translated 1662 BCP has commonly been called Te Rawiri ("the David"), reflecting the prominence of the Psalter in the services of Morning and Evening Prayer, as the Māori often looked for words to be attributed to a person of authority.[citation needed] The Māori translation of the 1662 BCP is still used in New Zealand, particularly among older Māori living in rural areas.

After earlier trial services in the mid-twentieth century, in 1988 the Anglican Church of Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia authorised through its general synod A New Zealand Prayer Book intended to serve the needs of New Zealand, Fiji, Tonga, Samoa and the Cook Island Anglicans. This book is unusual for its cultural diversity; it includes passages in the Māori, Fijian, Tongan and English languages. In other respects, it reflects the same ecumenical influence of the Liturgical Movement as in other new Anglican books of the period, and borrows freely from a variety of international sources. The book is not presented as a definitive or final liturgical authority, such as the use of the definite article in the title might have implied. While the preface is ambiguous regarding the status of older forms and books, the implication however is that this book is now the norm of worship for Anglicans in Aotearoa/New Zealand. The book has also been revised in a number of minor ways since the initial publication, such as by the inclusion of the Revised Common Lectionary and an online edition is offered freely as the standard for reference.

Australia

[edit]The Anglican Church of Australia, known officially until 1981 as the Church of England in Australia and Tasmania, became self-governing in 1961. Its general synod agreed that the Book of Common Prayer was to "be regarded as the authorised standard of worship and doctrine in this Church". After a series of experimental services offered in many dioceses during the 1960s and 70s, in 1978 An Australian Prayer Book was produced, formally as a supplement to the book of 1662, although in fact it was widely taken up in place of the old book. The AAPB sought to adhere to the principle that, where the liturgical committee could not agree on a formulation, the words or expressions of the Book of Common Prayer were to be used,[106] if in a modern idiom. The result was a conservative revision, including two forms of eucharistic rite: a First Order that was essentially the 1662 rite in more contemporary language, and a Second Order that reflected the Liturgical Movement norms, but without elements such as a eucharistic epiclesis or other features that would have represented a departure from the doctrine of the old book. An Australian Prayer Book has been formally accepted for usage in other churches, including the Reformed Episcopal Church in the United States.[107]

A Prayer Book for Australia, produced in 1995 and again not technically a substitute for the 1662 prayer book, nevertheless departed from both the structure and wording of the Book of Common Prayer, prompting conservative reaction. Numerous objections were made and the notably conservative evangelical Diocese of Sydney drew attention both to the loss of BCP wording and of an explicit "biblical doctrine of substitutionary atonement".[citation needed] Sydney delegates to the general synod sought and obtained various concessions but that diocese never adopted the book. The Diocese of Sydney has instead developed its own prayer book, called Sunday Services, to "supplement" the 1662 prayer book, and preserve the original theology which the Sydney diocese asserts has been changed. In 2009 the diocese published Better Gatherings which includes the book Common Prayer (published 2012), an updated revision of Sunday Services.[108][109][110]

North and Central America

[edit]Canada

[edit]The Anglican Church of Canada, which until 1955 was known as the Church of England in the Dominion of Canada, or simply the Church of England in Canada, developed its first Book of Common Prayer separately from the English version in 1918, which received final authorisation from General Synod on 16 April 1922.[111] The revision of 1959 was much more substantial, bearing a family relationship to that of the abortive 1928 book in England. The language was conservatively modernised, and additional seasonal material was added. As in England, while many prayers were retained though the structure of the Communion service was altered: a prayer of oblation was added to the eucharistic prayer after the "words of institution", thus reflecting the rejection of Cranmer's theology in liturgical developments across the Anglican Communion. More controversially, the Psalter omitted certain sections, including the entirety of Psalm 58.[b] General Synod gave final authorisation to the revision in 1962, to coincide with the 300th anniversary of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer. A French translation, Le Recueil des Prières de la Communauté Chrétienne, was published in 1967.

After a period of experimentation with the publication of various supplements, the Book of Alternative Services was published in 1985.

Indigenous languages

[edit]The Book of Common Prayer has also been translated into these North American indigenous languages: Cowitchan, Cree, Haida, Ntlakyapamuk, Slavey, Eskimo-Aleut, Dakota, Delaware, Mohawk, Ojibwe.[112]

Ojibwa

[edit]Joseph Gilfillan was the chief editor of the 1911 Ojibwa edition of the Book of Common Prayer entitled Iu Wejibuewisi Mamawi Anamiawini Mazinaigun (Iw Wejibwewizi Maamawi-anami'aawini Mazina'igan).[113]

United States

[edit]

The Episcopal Church separated itself from the Church of England in 1789, the first church in the American colonies having been founded in 1607.[114] The first Book of Common Prayer of the new body, approved in 1789, had as its main source the 1662 English book, with significant influence also from the 1764 Scottish Liturgy (see above) which Bishop Seabury of Connecticut brought to the US following his consecration in Aberdeen in 1784.

The preface to the 1789 Book of Common Prayer says, "this Church is far from intending to depart from the Church of England in any essential point of doctrine, discipline, or worship ... further than local circumstances require." There were some notable differences. For example, in the Communion service the prayer of consecration follows mainly the Scottish orders derived from 1549[115] and found in the 1764 Book of Common Prayer. The compilers also used other materials derived from ancient liturgies especially Eastern Orthodox ones such as the Liturgy of St. James.[115] An epiclesis or invocation of the Holy Spirit in the eucharistic prayer was included, as in the Scottish book, though modified to meet reformist objections. Overall however, the book was modelled on the English Prayer Book, the Convention having resisted attempts at more radical deletion and revision.[116]

Article X of the Canons of the Episcopal Church provides that "[t]he Book of Common Prayer, as now established or hereafter amended by the authority of this Church, shall be in use in all the Dioceses of this Church,"[117] which is a reference to the 1979 Book of Common Prayer.[c]

The Prayer Book Cross was erected in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park in 1894 as a gift from the Church of England.[d] Created by Ernest Coxhead, it stands on one of the higher points in Golden Gate Park. It is located between John F. Kennedy Drive and Park Presidio Drive, near Cross Over Drive. This 57 ft (17 m) sandstone cross commemorates the first use of the Book of Common Prayer in California by Sir Francis Drake's chaplain on 24 June 1579.

In 2019, the Anglican Church in North America released its own revised edition of the BCP.[118][119] It included a modernised rendering of the Coverdale Psalter, "renewed for contemporary use through efforts that included the labors of 20th century Anglicans T.S. Eliot and C.S. Lewis..."[120] According to Robert Duncan, the first archbishop of the ACNA, "The 2019 edition takes what was good from the modern liturgical renewal movement and also recovers what had been lost from the tradition."[121] The 2019 edition does not contain a catechism, but is accompanied by an extensive ACNA catechism, in a separate publication, To Be a Christian: An Anglican Catechism.[122]

Modern Catholic adaptations

[edit]Under Pope John Paul II's Pastoral Provision of the early 1980s, former Anglicans began to be admitted into new Anglican Use parishes in the US. The Book of Divine Worship was published in the United States in 2003 as a liturgical book for their use, composed of material drawn from the 1928 and 1979 Book of Common Prayer of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America and the Roman Missal.[123] It was mandated for use in all personal ordinariates for former Anglicans in the US from Advent 2013. Following the adoption of the ordinariates' Divine Worship: The Missal in Advent 2015, the Book of Divine Worship was suppressed.[124]

To complement the forthcoming Divine Worship missal, the newly erected Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of Walsingham in the UK authorised the usage of an interim Anglican Use Divine Office in 2012.[125] The Customary of Our Lady of Walsingham followed from both the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer tradition and that of the Catholic Church's Liturgy of the Hours, introducing hours – Terce, Sext, and None – not found in any standard Book of Common Prayer. Unlike other contemporary forms of the Catholic Divine Office, the Customary contained the full 150 Psalm psalter.[126]

In 2019, the St. Gregory's Prayer Book was published by Ignatius Press as a resource for all Catholic laity, combining selections from the Divine Worship missal with devotions drawn from various Anglican prayer books and other Anglican sources approved for Catholic use in a format that somewhat mimics the form and content of the Book of Common Prayer.[127]

In 2020, the first of two editions of Divine Worship: Daily Office was published. While the North American Edition was the first Divine Office introduced in the Personal Ordinariate of the Chair of Saint Peter, the Commonwealth Edition succeeded the previous Customary for the Personal Ordinariates of Our Lady of Walsingham and Our Lady of the Southern Cross. The North American Edition more closely follows the American 1928, American 1979, and Canadian 1962 prayer books, while the Commonwealth Edition more closely follows the precedents set by the Church of England's 1549 and 1662 Book of Common Prayer.[128]

Religious influence

[edit]The Book of Common Prayer has had a great influence on a number of other denominations. While theologically different, the language and flow of the service of many other churches owe a great debt to the prayer book. In particular, many Christian prayer books have drawn on the Collects for the Sundays of the Church Year – mostly freely translated or even "rethought"[129] by Cranmer from a wide range of Christian traditions, but including a number of original compositions – which are widely recognised as masterpieces of compressed liturgical construction.

John Wesley, an Anglican priest whose revivalist preaching led to the creation of Methodism wrote in his preface to The Sunday Service of the Methodists in North America (1784), "I believe there is no Liturgy in the world, either in ancient or modern language, which breathes more of a solid, scriptural, rational piety than the Common Prayer of the Church of England."[130] Many Methodist churches in England and the United States continued to use a slightly revised version of the book for communion services well into the 20th century. In the United Methodist Church, the liturgy for eucharistic celebrations is almost identical to what is found in the Book of Common Prayer, as are some of the other liturgies and services.

A unique variant was developed in 1785 in Boston, Massachusetts when the historic King's Chapel (founded 1686) left the Episcopal Church and became an independent Unitarian church. To this day, King's Chapel uniquely uses The Book of Common Prayer According to the Use in King's Chapel in its worship; the book eliminates trinitarian references and statements.

Literary influence

[edit]Along with the King James Version of the Bible and the works of Shakespeare, the Book of Common Prayer has been one of the major influences on modern English parlance. As it has been in regular use for centuries, many phrases from its services have passed into everyday English, either as deliberate quotations or as unconscious borrowings. They have often been used metaphorically in non-religious contexts, and authors have used phrases from the prayer book as titles for their books.

… Therefore if any man can shew any just cause, why they may not lawfully be joined together, let him now speak, or else hereafter for ever hold his peace …

Blessed Lord, who hast caused all holy Scriptures to be written for our learning: Grant that we may in such wise hear them, read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest them, that by patience and comfort of thy holy Word, we may embrace and ever hold fast the blessed hope of everlasting life, which thou hast given us in our Saviour Jesus Christ. Amen.

Some examples of well-known phrases from the Book of Common Prayer are:

- "Speak now or forever hold your peace" from the marriage liturgy.

- "Till death us do part", from the marriage liturgy.[e][131]

- "Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust" from the funeral service.

- "In the midst of life, we are in death" from the committal in the service for the burial of the dead (first rite).

- "From all the deceits of the world, the flesh, and the devil" from the litany.

- "Read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest" from the collect for the second Sunday of Advent.

- "Evil liver" from the rubrics for Holy Communion.

- "All sorts and conditions of men" from the Order for Morning Prayer.

- "Peace in our time" from Morning Prayer, Versicles.

References and allusions to Prayer Book services in the works of Shakespeare were tracked down and identified by Richmond Noble.[132] Derision of the Prayer Book or its contents "in any interludes, plays, songs, rhymes, or by other open words" was a criminal offence under the 1559 Act of Uniformity, and consequently Shakespeare avoids too direct reference; but Noble particularly identifies the reading of the Psalter according to the Great Bible version specified in the Prayer Book, as the biblical book generating the largest number of Biblical references in Shakespeare's plays. Noble found a total of 157 allusions to the Psalms in the plays of the First Folio, relating to 62 separate Psalms – all, save one, of which he linked to the version in the Psalter, rather than those in the Geneva Bible or Bishops' Bible. In addition, there are a small number of direct allusions to liturgical texts in the Prayer Book; e.g. Henry VIII 3:2 where Wolsey states "Vain Pomp and Glory of this World, I hate ye!", a clear reference to the rite of Public Baptism; where the Godparents are asked "Doest thou forsake the vaine pompe and glory of the worlde..?"

As novelist P. D. James observed, "We can recognize the Prayer Book's cadences in the works of Isaac Walton and John Bunyan, in the majestic phrases of John Milton, Sir Thomas Browne and Edward Gibbon. We can see its echo in the works of such very different writers as Daniel Defoe, Thackeray, the Brontës, Coleridge, T. S. Eliot and even Dorothy L. Sayers."[133] James herself used phrases from the Book of Common Prayer and made them into best-selling titles – Devices and Desires and The Children of Men – while Alfonso Cuarón's 2006 film Children of Men placed the phrase onto cinema marquees worldwide.

Copyright status

[edit]In England there are only three bodies entitled to print the Book of Common Prayer: the two privileged presses (Cambridge University Press and Oxford University Press), and The King's Printer. Cambridge University Press holds letters patent as The King's Printer and so two of these three bodies are the same. The Latin term cum privilegio ("with privilege") is printed on the title pages of Cambridge editions of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer (and the King James Version of the Bible) to denote the charter authority or privilege under which they are published.

The primary function for Cambridge University Press in its role as King's Printer is preserving the integrity of the text, continuing a long-standing tradition and reputation for textual scholarship and accuracy of printing. Cambridge University Press has stated that as a university press, a charitable enterprise devoted to the advancement of learning, it has no desire to restrict artificially that advancement, and that commercial restrictiveness through a partial monopoly is not part of its purpose. It therefore grants permission to use the text, and licence printing or the importation for sale within the UK, as long as it is assured of acceptable quality and accuracy.[f]

The Church of England, supported by the Prayer Book Society, publishes an online edition of the Book of Common Prayer with permission of Cambridge University Press.

In accordance with Canon II.3.6(b)(2) of the Episcopal Church (United States), the church relinquishes any copyright for the version of the Book of Common Prayer currently adopted by the Convention of the church (although the text of proposed revisions remains copyrighted).[g]

Editions

[edit]- Anglican Church of Canada (1962), The Book of Common Prayer, Toronto: Anglican Book Centre Publishing, p. 736, ISBN 0-921846-71-1

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Anglican Church of Canada (1964). The Canadian Book of Occasional Offices: Services for Certain Occasions not Provided in the Book of Common Prayer, compiled by the Most Rev. Harold E. Sexton, Abp. of British Columbia, published at the request of the House of Bishops of the Anglican Church of Canada. Toronto: Anglican Church of Canada, Dept. of Religious Education. x, 162 p.

- Anglican Catholic Church of Canada (198-?). When Ye Pray: Praying with the Church, [by] Roland F. Palmer [an editor of the 1959/1962 Canadian B.C.P.]. Ottawa: Anglican Catholic Convent Society. N.B.: "This book is a companion to the Prayer Book to help ... to use the Prayer Book better." – Pg. 1. Without ISBN

- Reformed Episcopal Church in Canada and Newfoundland (1892). The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, According to the Use of the Reformed Episcopal Church in the Dominion of Canada, Otherwise Known as the Protestant Church of England. ... Toronto, Ont.: Printed ... by the Ryerson Press ... for the Synod of Canada, 1951, t.p. verso 1892. N.B.: This is the liturgy as it had been authorised in 1891.

- Church of England (1977) [1549 & 1552], The First and Second Prayer Books of King Edward VI, London: Everyman's Library, ISBN 0-460-00448-4

- Church of England (1999) [1662], The Book of Common Prayer, London: Everyman's Library, ISBN 1-85715-241-7

- Church in Wales (1984). The Book of Common Prayer, for the Use in the Church in Wales. Penarth, Wales: Church in Wales Publications. 2 vol. N.B.: Title also in Welsh on vol. 2: Y Llfr Gweddi Giffredin i'w arfer yn Yr Eglwys yng Nghymru; vol. 1 is entirely in English; vol. 2 is in Welsh and English on facing pages. Without ISBN

- Cummings, Brian, ed. (2011) [1549, 1559 & 1662]. The Book of Common Prayer: The Texts of 1549, 1559, and 1662. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-964520-6.

- Reformed Episcopal Church (U.S.)(1932). The Book of Common Prayer, According to the Use of the Reformed Episcopal Church in the United States of America. Rev. fifth ed. Philadelphia, Penn.: Reformed Episcopal Publication Society, 1963, t.p. 1932. xxx, 578 p. N.B.: On p. iii: "[T]he revisions made ... in the Fifth Edition [of 1932] are those authorized by the [Reformed Episcopal] General Councils from 1943 through 1963."

- The Episcopal Church (1979), The Book of Common Prayer (1979), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-528713-4

- The Episcopal Church (2003). The Book of Common Prayer: Selected Liturgies ... According to the Use of the Episcopal Church = Le Livre de la prière commune: Liturgies sélectionnées ... selon l'usage de l'Eglise Épiscopale. Paris: Convocation of American Churches in Europe. 373, [5] p. N.B.: Texts in English and as translated into French, from the 1979 B.C.P. of the Episcopal Church (U.S.), on facing pages. ISBN 0-89869-448-5

- The Episcopal Church (2007). The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church". New York, Church Publishing Incorporated. N.B.: "...amended by action of the 2006 General Convention to include the Revised Common Lectionary." (Gregory Michael Howe, February 2007) ISBN 0-89869-060-9

- The Church of England in Australia Trust Corporation (1978), An Australian Prayer Book, St.Andrew's House, Sydney Square, Sydney: Anglican Information Office Press, pp. 636 p, ISBN 0-909827-79-6

- A Book of Common Prayer: … Set Forth by Authority for Use in the Church of the Province of South Africa. Oxford. 1965.

See also

[edit]- Anglican devotions

- Anglican Service Book

- Prayer Book Rebellion

- Prayer Book Society of Canada

- The Books of Homilies

- Metrical psalter

- Book of Common Prayer (1843 illustrated version)

- Book of Common Prayer (1845 illuminated version)

16th century Protestant hymnals

[edit]Anabaptist

Anglican

Lutheran

- First Lutheran hymnal

- Erfurt Enchiridion

- Eyn geystlich Gesangk Buchleyn

- Swenske songer eller wisor 1536

- Thomissøn's hymnal

Presbyterian

Reformed

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Widely varying figures are quoted. Procter & Frere 1902 gave 2000; Neill 1960, p. 165, 1760. Spurr gives the following breakdown for the period 1660–63: Total ministers forced out of English parishes about 1760. This includes 695 parish ministers ejected under the 1660 act for settling clergy; 936 more forced out under the 1662 Act of Uniformity. In addition 200 non-parochial ministers from lectureships, universities and schools, and 120 in Wales were excluded. He adds that 171 of the 1760 are "known to have conformed later". In a footnote he cites Pruett 1978, pp. 17, 18, 23.

- ^ According to the "Tables of Proper Psalms". Archived from the original on 3 September 2009., "The following passages in the Psalter as hitherto used are omitted: Psalm 14. 5–7; 55. 16; 58 (all); 68. 21–23; 69. 23–29; 104. 35 (in part); 109. 5–19; 136. 27; 137. 7–9; 140. 9–10; 141. 7–8. The verses are renumbered." See also the "Psalter from 1962 Canadian Book of Common Prayer". Archived from the original on 21 May 2009.

- ^ Some parishes continued to use the 1928 book either regularly or occasionally, for pastoral sensitivity, for doctrinal reasons and for the beauty of its language. See "Parishes using the Historic Book of Common Prayer". Archived from the original on 22 June 2009. Retrieved 28 April 2010. The controversies surrounding the Book of Common Prayer contrasts with the Episcopal Church's description of it as "the primary symbol of our unity." Diverse members "come together" through "our common prayer." See "The Book of Common Prayer". episcopalchurch.org. 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ A picture of the Prayer Book Cross can be seen at "Prayer Book Cross". Archived from the original on 11 February 2005. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- ^ The phrase "till death us do part" ("till death us depart" before 1662) has been changed to "till death do us part" in some more recent prayer books, such as the 1962 Canadian Book of Common Prayer.

- ^ See "The Queen's Printer's Patent". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- ^ See the "Constitution & Canons" (PDF). generalconvention.org. The General Convention of the Episcopal Church. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Careless 2003, p. 26.

- ^ Church of England 1662.

- ^ Careless 2003, p. 23.

- ^ "The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments". brbl-dl.library.yale.edu. Yale University. Retrieved 11 December 2017 – via Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- ^ Harrison & Sansom 1982, p. 29.

- ^ Leaver 2006, p. 39.

- ^ MacCulloch 1996, p. 331.

- ^ MacCulloch 1996, p. 60.

- ^ Procter & Frere 1965, p. 31.

- ^ a b Jeanes 2006, p. 23.

- ^ MacCulloch 1996, p. 417.

- ^ Jeanes 2006, p. 27.

- ^ Gibson 1910.

- ^ a b c Jeanes 2006, p. 26.

- ^ MacCulloch 1996, p. 418.

- ^ Jeanes 2006, p. 30.

- ^ a b MacCulloch 1996, p. 412.

- ^ Jeanes 2006, p. 31.

- ^ Moorman 1983, p. 26.

- ^ Duffy 2005, pp. 464–466.

- ^ Jeanes 2006, p. 28.

- ^ Moorman 1983, p. 27.