Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

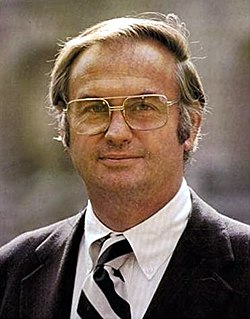

Lowell Weicker

View on Wikipedia

Lowell Palmer Weicker Jr. (/waɪkər/; May 16, 1931 – June 28, 2023) was an American politician who served as a U.S. representative, U.S. senator, and the 85th governor of Connecticut.

Key Information

Weicker unsuccessfully sought the Republican nomination for president in 1980. One of the first Republican members of Congress to express concerns about President Richard Nixon's role in the Watergate scandal, Weicker developed a reputation as a "Rockefeller Republican", eventually leading conservative activists to endorse his opponent Joe Lieberman, a New Democrat, in the 1988 Senate election which he subsequently lost. Weicker later left the Republican Party, and became one of the few third-party candidates to be elected to a state governorship in the United States at the time, doing so on the ticket of A Connecticut Party.

Early life

[edit]Weicker was born in Paris, the son of American parents Mary Hastings (née Bickford) and Lowell Palmer Weicker.[1] His grandfather Theodore Weicker was a German immigrant who co-founded the E. R. Squibb corporation.[2][3] Weicker graduated from the Lawrenceville School (class of 1949), Yale University (1953), and the University of Virginia School of Law (1958).[4] He began his political career after serving in the United States Army between 1953 and 1955, reaching the rank of first lieutenant.[5]

Career in Congress

[edit]Weicker served in the Connecticut State House of Representatives from 1963 to 1969 and as First Selectman of Greenwich, Connecticut, before winning election to the U.S. House of Representatives, in 1968 as a Republican. Weicker only served one term in the House before being elected to the U.S. Senate in 1970.[6][7] Weicker benefited from a split in the Democratic Party in that election: two-term incumbent Thomas Dodd ran as an independent after losing the Democratic nomination to Joseph Duffey.[8] Ultimately, Weicker won with 41.7 percent of the vote. Dodd finished third, with 266,500 votes—far exceeding Weicker's 86,600-vote margin over Duffey.[9][10]

Weicker served in the U.S. Senate for three terms, from 1971 to 1989. He gained national attention for his service on the Senate Watergate Committee, where he became the first Republican senator to call for Richard Nixon's resignation.[11] He recalled: "People in Connecticut were very much behind President Nixon, like the rest of the country. They thought he could do no wrong, and when I was in Connecticut, I would get flipped the bird all the time, whether it was on the streets or in the car, for the role that I was playing. After Watergate was over, then the needle goes all the way the other way, and I've got huge favorability ratings."[12] Proving this, Weicker was convincingly reelected in 1976.[13]

In 1980, he made an unsuccessful bid for the Republican nomination for president.[14]

Weicker was a liberal voice in an increasingly conservative Republican Party. For instance Americans for Democratic Action consistently rated Weicker as having a liberal quotient of 60 to 90% throughout his Senate career, and in 1987 and in 1988 gave him a higher rating than Connecticut's other senator, Democrat Chris Dodd.[15] He was critical of the increasing influence of the Christian right on the party; he described the separation of church and state as "this country's greatest contribution to world civilization",[16] and the party in 2012 as "swung off so far to the right that no moderate could've survived a primary."[12] Weicker voted in favor of the bill establishing Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a federal holiday and the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1987 (as well as to override President Reagan's veto).[17][18][19] Weicker voted against the nomination of William Rehnquist as Chief Justice of the United States,[20] as well as the nomination of Robert Bork to the U.S. Supreme Court.[21]

Weicker was a strong advocate for the rights of the disabled during his tenure in Congress, although he ultimately lost his seat before the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 passed.[22] In later interviews, Weicker identified his work on the Americans with Disabilities Act, funding the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, increasing the funding for the National Institutes of Health, and funding research into AZT as his proudest achievements in the Senate.[23][12]

Weicker's rocky relations with establishment Republicans may have roots in receiving strong support from Nixon in his 1970 Senate bid, support repaid in the eyes of his critics by a vehement attack on the White House while serving on the Watergate Committee.[24] Later, his relations with the Bush family also soured, and Prescott Bush Jr. (the brother of the then Vice President) made a short-lived bid against Weicker to gain the 1982 Republican Senate nomination.[25] Weicker's well-known Democratic sympathies increasingly alienated mainstream Republicans, particularly after Weicker’s effort to prevent the nomination of conservatives to state office, which resulted in a poor showing during the 1986 local elections, and he was defeated in the 1988 Senate election by Joe Lieberman.[11][16] Lieberman benefited from the support of National Review founder William F. Buckley Jr., and his brother, former New York Senator James Buckley; William F. Buckley ran columns in support of Lieberman and circulated bumper stickers with the slogan, "Does Lowell Weicker Make You Sick?"[16]

-

Weicker greeting Gerald Ford in 1976

-

Weicker with Ronald Reagan in 1988

-

Weicker campaigning with George H. W. Bush in 1988

Governor of Connecticut

[edit]Weicker's political career appeared to be over after his 1988 defeat, and he became a professor at the George Washington University Law School. However, he entered the 1990 gubernatorial election as the candidate of A Connecticut Party, running as a good government candidate[26] and drew upon his coalition of liberal Republicans, moderate Democrats, and independent voters.[16] The early 1990s recession had hit Connecticut hard, worsened by the fall in revenues from traditional sources such as sales tax and corporation tax.[27] Connecticut politics had a tradition at the time of opposition to a state income tax—one had been implemented in 1971 but rescinded after six weeks under public pressure.[28][16] Weicker initially campaigned on a platform of solving Connecticut's fiscal crisis without implementing an income tax. He won in a three-way race with Republican John G. Rowland and Democrat Bruce Morrison, taking 40% of the vote against Rowland's 37% and Morrison's 21%. Weicker lost Fairfield and New Haven County counties to Rowland, but won eastern Connecticut, drawing especially strong support from the Hartford metro area, where he had been strongly endorsed by the Hartford Courant and by many state employee labor unions. The Los Angeles Times wrote that support from Democrats was credited for Weicker's victory, reflected in Morrison's third-place finish.[11]

After taking office, with a projected $2.4 billion deficit,[29][27] Weicker reversed himself and pushed for the adoption of an income tax, a move that was very unpopular.[27][16] He stated, "My policy when I came in was no income tax, but that fell apart on the rocks of fiscal fact."[30] Weicker vetoed three budgets that did not contain an income tax, and forced a partial government shutdown, before the General Assembly narrowly passed it in 1991.[28] The 1991 budget set the income tax rate at 6%,[31] lowered the sales tax from 8% to 6% while expanding its base, reduced the corporate tax to 10.5% over two years, and eliminated taxes on capital gains, interest, and dividends.[28][29] It also included $1.2 billion in line-by-line budget cuts,[30] including the elimination of state aid to private and parochial schools, but held the line on social programs.[16] His drastic measures provoked controversy.[27] A huge protest rally in Hartford attracted some 40,000 participants, some of whom cursed at and spat at Governor Weicker.[16][26]

Weicker earned lasting criticism for his implementation of the income tax; the conservative Yankee Institute claimed in August 2006 that after fifteen years the income tax had failed to achieve its stated goals.[32] However, he earned national attention for his leadership on the issue, receiving the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation's Profile in Courage Award for taking an unpopular stand, then holding firm.[33] Within two years, the state's budget was in surplus and he was well-regarded among voters.[16] In retirement, he commented, "You've had 19 years to repeal it, and all you've done is spend it."[23][12]

Despite his increasing popularity, he did not seek re-election as governor in 1994, citing wanting to spend time with his children as the reason. His last year in office was marked by a controversy over the firing of the state commissioner of motor vehicles, Louis Goldberg.[26] In 2000, he endorsed Senator Bill Bradley (D-NJ) for President. In 2004, Weicker supported former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean's (D-VT) presidential bid. He expressed sympathy for the budget struggles of Governor Dannel Malloy, drawing a parallel with his own efforts to remedy a fiscal crisis.[23][12]

In his book Independent Nation (2004), political analyst John Avlon describes Weicker as a radical centrist governor and thinker.[34]

Later career

[edit]

Weicker published a memoir entitled Maverick in 1995, co-written with Barry Sussman.[24][6] The following year, he joined the board of directors for Compuware.[35] In 1999, he became a member of the board of directors for the World Wrestling Federation (now known as WWE), and held this position until 2011.[36] Despite the long professional relationship, Weicker did not support former WWE CEO Linda McMahon in either of her unsuccessful bids for the U.S. Senate in 2010 or 2012.[37]

Weicker served from 2001 to 2011 as president of the board of directors of Trust for America's Health, a Washington, DC–based non-profit, non-partisan health policy research organization and was formerly a member of the board of directors of United States Tobacco. From 2003 on Weicker served on the board of Medallion Financial Corp., a lender to purchasers of taxi medallions in leading cities across the U.S. He was named to the board through his personal and business relationship with Andrew M. Murstein, president of Medallion.[38]

Weicker considered a rematch against Senator Joe Lieberman in 2006. He objected to Lieberman's support for the Iraq War and told The New York Times in 2005, "If he's out there scot-free and nobody will do it [run against Senator Lieberman], I'd have to give serious thought to doing it myself, and I don't want to do it."[39] Weicker ultimately did not run, but he endorsed Ned Lamont, who defeated Lieberman in the Democratic primary, causing Lieberman to run as an independent.[24] The Lieberman campaign released an ad that borrowed from one aired during the 1988 Senate race, which depicted Weicker as a hibernating bear ignoring his Senate duties except at election time. In the 2006 ad, Weicker reappeared as a wounded bear while Lieberman's Democratic challenger, Lamont, was depicted as a bear cub sent and directed by Weicker. Lieberman ultimately defeated Lamont in November.[40]

In 2015, despite criticizing Cuba for its lack of "human rights and democratic elections", Weicker described the country's free healthcare system as one of its most positive aspects.[41]

During the 2016 Republican primaries, Weicker wrote an editorial in the Hartford Courant in which he criticized the repudiation of Rockefeller Republicans, the party's alienation of various population groups, and its obstructionist stance in Congress. He stated that the selection of Donald Trump as their presidential candidate "will complete their slow and steady descent into irrelevance."[42]

In 2020, he filed an amicus brief on the side of Pennsylvania in the notable election case Texas v. Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania won the case and Biden was sworn in shortly after. Weicker had served with Biden in the U.S. Senate for 16 years.[43]

Personal life and death

[edit]Weicker lived in Old Lyme, Connecticut, in his later years.[6] He was married three times and had five sons.[6] His first marriage, to Marie Louise Godfrey, lasted from 1953 to their divorce in 1977.[24] He then married Camille Butler, his secretary. Their six-year marriage was described by The Connecticut Mirror as "tumultuous", and it ended in divorce.[24] His third marriage, to Claudia Testa Ingram, lasted from 1984 until Weicker's death, at Middlesex Hospital in Middletown, Connecticut, on June 28, 2023, at age 92.[24][44] Weicker is interred at the Putnam Cemetery in Greenwich, Connecticut.[45] By the time of his death, he was the last living former member of the Senate Watergate Committee.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "NEHGS – Articles". Archived from the original on January 14, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2009.

- ^ Ravo, Nick (August 27, 1990). "Weicker Honeymoon Over as Governor's Race Heats Up". The New York Times. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ "Merck in America: the first 70 years from fine chemicals to pharmaceutical giant" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2018.

- ^ Lowell Palmer Weicker Jr., Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed December 16, 2007.

- ^ "Weicker Formally Enters Congress Race in Fourth". The Bridgeport Telegram. December 1, 1967. Retrieved September 20, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Johnson, Kirk (June 29, 2023). "Lowell Weicker, 92, Maverick Connecticut Senator and Governor, Dies". The New York Times. p. A20. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- ^ Stewart, Doug (June 28, 2023). "Former Connecticut Gov. Lowell Weicker dies at 92". WTIC-TV. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ Bumiller, Elisabeth (September 24, 2007). "Dodd's Other Campaign: Restoring Dad's Reputation". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "An Unrepresented Majority". The Des Moines Register. November 7, 1970. p. 4. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ "Senate Contests". Globe Gazette. November 4, 1970. p. 2. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c Mehren, Elizabeth (July 1, 1991). "A Taxing Situation : Politics: Connecticut Gov. Lowell Weicker loves a challenge. He's facing his biggest one yet by proposing the state's first income tax to solve its budget mess". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Bendici, Ray (August 1, 2012). "Final Say: Lowell Weicker". Connecticut Magazine. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ Susan Haigh (June 28, 2023). "Lowell Weicker, Connecticut Senator, Governor, Dies". Associated Press.

- ^ Weicker Opens Presidential Campaign[permanent dead link], March 13, 1979

- ^ Kornacki, Steve (January 19, 2011) The making (and unmaking) of Joe Lieberman Archived June 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Salon

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Avlon, John (February 24, 2004). Independent Nation: How the Vital Center Is Changing American Politics. Crown/Archetype. ISBN 9781400080724.

- ^ "TO PASS H.R. 3706. (MOTION PASSED) SEE NOTE(S) 19".

- ^ "TO PASS S 557, CIVIL RIGHTS RESTORATION ACT, A BILL TO RESTORE THE BROAD COVERAGE AND CLARIFY FOUR CIVIL RIGHTS LAWS BY PROVIDING THAT IF ONE PART OF AN INSTITUTION IS FEDERALLY FUNDED, THEN THE ENTIRE INSTITUTION MUST NOT DISCRIMINATE".

- ^ "TO ADOPT, OVER THE PRESIDENT'S VETO OF S 557, CIVIL RIGHTS RESTORATION ACT, A BILL TO RESTORE BROAD COVERAGE OF FOUR CIVIL RIGHTS LAWS BY DECLARING THAT IF ONE PART OF AN INSTITUTION RECEIVES FEDERAL FUNDS, THEN THE ENTIRE INSTITUTION MUST NOT DISCRIMINATE. TWO-THIRDS OF THE SENATE, HAVING VOTED IN THE AFFIRMATIVE, OVERRODE THE PRESIDENTIAL VETO".

- ^ "Congressional Record—Senate" (PDF). United States Senate. September 17, 1986. p. 23803. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "Senate Rejects Bork, 58–42 : Six Republicans Bolt Party Ranks to Oppose Judge". Los Angeles Times. October 23, 1987. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ Disabilities, The Minnesota Governor's Council on Developmental. "The ADA Legacy Project: Moments in Disability History 13: Lowell P. Weicker, Jr., Original "Father" of the Americans with Disabilities Act". mn.gov.

- ^ a b c Vigdor, Neil (May 15, 2011). "A Connecticut political maverick turns 80: Lowell Weicker Jr". The Advocate. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Pazniokas, Mark (June 28, 2023). "Lowell Weicker, Connecticut governor and U.S. senator, dies at 92". The Connecticut Mirror. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ^ Madden, Richard L. (July 28, 1982). "BUSH ABANDONS CONNECTICUT BID FOR SENATE SEAT". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Byron, Christopher (January 10, 1994). Playing Favorites. New York.

- ^ a b c d Mehren, Elizabeth (July 1, 1991). "A Taxing Situation : Politics: Connecticut Gov. Lowell Weicker loves a challenge. He's facing his biggest one yet by proposing the state's first income tax to solve its budget mess". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Kirk (August 23, 1991). "Budget Is Passed for Connecticut With Income Tax". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "Budget Address by Governor Lowell P. Weicker, Jr., to a Joint Session of the Connecticut General Assembly, 13 February 1991". Yankee Institute for Public Policy. February 13, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Ellis, David (April 13, 1992). "The Gutsiest Governor In America: Lowell Weicker". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ Mehren, Elizabeth (July 1, 1991). "A Taxing Situation: Politics: Connecticut Gov. Lowell Weicker loves a challenge. He's facing his biggest one yet by proposing the state's first income tax to solve its budget mess". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ "Fifteen Years of Folly: The Failures of Connecticut's Income Tax" (PDF). Yankee Institute for Public Policy. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2007. Retrieved August 28, 2006.

- ^ Johnson, Kirk (May 31, 1992). "MAY 24–30: Profile in Courage; Lowell Weicker Jr. Wants Washington To Take Note". New York Times. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ Avlon, John (2004). Independent Nation: How the Vital Center Is Changing American Politics. Harmony Books / Random House, pp. 177–93 ("Radical Centrists"). ISBN 978-1-4000-5023-9.

- ^ "COMPUWARE CORPORATION, Form DEF 14A, Filing Date Jul 22, 2002". secdatabase.com. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ "The breakup: Weicker to leave the board of WWE", GreenwichTime.com, April 18, 2011

- ^ Neil Vigdor (September 14, 2012). "Backing Murphy, Weicker disparages McMahon's credentials". Connecticut Post. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ Medallion Financial Corp. annual report, 2010, p. 78

- ^ Yardley, William (December 6, 2005). "Weicker May Return to Politics Over Lieberman's Support of War". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 27, 2018. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ "CNN.com – Elections 2006". CNN. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- ^ "Former Governor Lowell Weicker Lauds President Obama's New Openness to Cuba".

- ^ Weicker, Jr., Lowell (May 14, 2016). "Weicker: Trump Signals Sunset Of Republican Party". Hartford Courant. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ^ Adler, Jonathan H. (December 9, 2020). "Additional Filings in and Additional Thoughts on the Texas Election Suit". The Volokh Conspiracy. Reason. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2020.

- ^ "Senator Weicker Weds Claudia Ingram". The New York Times. December 22, 1984. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ Fenster, Jordan Nathaniel (July 23, 2023). "Funeral for Gov. Lowell Weicker to be held Monday in Greenwich". Greenwich Time. Retrieved August 13, 2025.

Further reading

[edit]- Weicker, Lowell P. (with Barry Sussman) (1995). Maverick: A Life in Politics. Little Brown & Co. ISBN 978-0-316-92814-4. (Memoir)

- Barone, Michael, et al. The Almanac of American Politics 1976: The Senators, the Representatives and the Governors: Their Records and Election Results, Their States and Districts (1975); new editions every 2 years through the 1996 editions cover his political career

- Lowell Weicker's papers are held at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library at the University of Virginia

External links

[edit]Lowell Weicker

View on GrokipediaLowell Palmer Weicker Jr. (May 16, 1931 – June 28, 2023) was an American politician who represented Connecticut in the United States House of Representatives from 1969 to 1971 and in the Senate from 1971 to 1989 before serving as the state's 85th governor from 1991 to 1995 as an independent.[1][2] Born in Paris, France, to American parents, Weicker graduated from Yale University in 1953 and the University of Virginia School of Law in 1958, later entering politics after service in the Connecticut General Assembly and as first selectman of Greenwich.[1][3] During his Senate tenure as a Republican, Weicker gained national prominence as a member of the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, where he was the first senator from his party to publicly call for President Richard Nixon's resignation amid the Watergate scandal revelations.[4][5] Known for his maverick stance, he frequently diverged from conservative orthodoxy, including opposition to some Reagan administration policies, and sought the Republican presidential nomination in 1980.[6][7] After losing his 1988 Senate re-election bid to Democrat Joe Lieberman, Weicker campaigned successfully for governor under the banner of A Connecticut Party, marking the first independent gubernatorial victory in the state since the Civil War era.[8][3] As governor, Weicker addressed a severe budget shortfall by enacting Connecticut's first broad-based personal income tax in 1991, initially set at a flat rate of 4.5 percent, which replaced temporary surcharges and sales tax hikes but drew widespread opposition for expanding the tax burden despite campaign ambiguities on the issue.[9][8] This fiscal overhaul balanced the state budget yet alienated voters and members of both major parties, contributing to his unpopularity and decision against seeking re-election in 1994.[10][11]