Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Atmospheric entry

View on Wikipedia

Atmospheric entry (sometimes listed as Vimpact or Ventry) is the movement of an object from outer space into and through the gases of an atmosphere of a planet, dwarf planet, or natural satellite. Atmospheric entry may be uncontrolled entry, as in the entry of astronomical objects, space debris, or bolides. It may be controlled entry (or reentry) of a spacecraft that can be navigated or follow a predetermined course. Methods for controlled atmospheric entry, descent, and landing of spacecraft are collectively termed as EDL.

Objects entering an atmosphere experience atmospheric drag, which puts mechanical stress on the object, and aerodynamic heating—caused mostly by compression of the air in front of the object, but also by drag. These forces can cause loss of mass (ablation) or even complete disintegration of smaller objects, and objects with lower compressive strength can explode.

Objects have reentered with speeds ranging from 7.8 km/s for low Earth orbit to around 12.5 km/s for the Stardust probe.[1] They have high kinetic energies, and atmospheric dissipation is the only way of expending this, as it is highly impractical to use retrorockets for the entire reentry procedure. Crewed space vehicles must be slowed to subsonic speeds before parachutes or air brakes may be deployed.

Ballistic warheads and expendable vehicles do not require slowing at reentry, and in fact, are made streamlined so as to maintain their speed. Furthermore, slow-speed returns to Earth from near-space such as high-altitude parachute jumps from balloons do not require heat shielding because the gravitational acceleration of an object starting at relative rest from within the atmosphere itself (or not far above it) cannot create enough velocity to cause significant atmospheric heating.

For Earth, atmospheric entry occurs by convention at the Kármán line at an altitude of 100 km (62 miles; 54 nautical miles) above the surface, while at Venus atmospheric entry occurs at 250 km (160 mi; 130 nmi) and at Mars atmospheric entry occurs at about 80 km (50 mi; 43 nmi). Uncontrolled objects reach high velocities while accelerating through space toward the Earth under the influence of Earth's gravity, and are slowed by friction upon encountering Earth's atmosphere. Meteors are also often travelling quite fast relative to the Earth simply because their own orbital path is different from that of the Earth before they encounter Earth's gravity well. Most objects enter at hypersonic speeds due to their sub-orbital (e.g., intercontinental ballistic missile reentry vehicles), orbital (e.g., the Soyuz), or unbounded (e.g., meteors) trajectories. Various advanced technologies have been developed to enable atmospheric reentry and flight at extreme velocities. An alternative method of controlled atmospheric entry is buoyancy[2] which is suitable for planetary entry where thick atmospheres, strong gravity, or both factors complicate high-velocity hyperbolic entry, such as the atmospheres of Venus, Titan and the giant planets.[3]

History

[edit]

The concept of the ablative heat shield was described as early as 1920 by Robert Goddard: "In the case of meteors, which enter the atmosphere with speeds as high as 30 miles (48 km) per second, the interior of the meteors remains cold, and the erosion is due, to a large extent, to chipping or cracking of the suddenly heated surface. For this reason, if the outer surface of the apparatus were to consist of layers of a very infusible hard substance with layers of a poor heat conductor between, the surface would not be eroded to any considerable extent, especially as the velocity of the apparatus would not be nearly so great as that of the average meteor."[4]

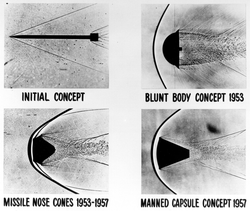

Practical development of reentry systems began as the range, and reentry velocity of ballistic missiles increased. For early short-range missiles, like the V-2, stabilization and aerodynamic stress were important issues (many V-2s broke apart during reentry), but heating was not a serious problem. Medium-range missiles like the Soviet R-5, with a 1,200-kilometer (650-nautical-mile) range, required ceramic composite heat shielding on separable reentry vehicles (it was no longer possible for the entire rocket structure to survive reentry). The first ICBMs, with ranges of 8,000 to 12,000 km (4,300 to 6,500 nmi), were only possible with the development of modern ablative heat shields and blunt-shaped vehicles.

In the United States, this technology was pioneered by H. Julian Allen and A. J. Eggers Jr. of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) at Ames Research Center.[5] In 1951, they made the counterintuitive discovery that a blunt shape (high drag) made the most effective heat shield.[6] From simple engineering principles, Allen and Eggers showed that the heat load experienced by an entry vehicle was inversely proportional to the drag coefficient; i.e., the greater the drag, the less the heat load. If the reentry vehicle is made blunt, air cannot "get out of the way" quickly enough, and acts as an air cushion to push the shock wave and heated shock layer forward (away from the vehicle). Since most of the hot gases are no longer in direct contact with the vehicle, the heat energy would stay in the shocked gas and simply move around the vehicle to later dissipate into the atmosphere.

The Allen and Eggers discovery, though initially treated as a military secret, was eventually published in 1958.[7]

Terminology, definitions and jargon

[edit]

When atmospheric entry is part of a spacecraft landing or recovery, particularly on a planetary body other than Earth, entry is part of a phase referred to as entry, descent, and landing, or EDL.[8] When the atmospheric entry returns to the same body that the vehicle had launched from, the event is referred to as reentry (almost always referring to Earth entry).

The fundamental design objective in atmospheric entry of a spacecraft is to dissipate the energy of a spacecraft that is traveling at hypersonic speed as it enters an atmosphere such that equipment, cargo, and any passengers are slowed and land near a specific destination on the surface at zero velocity while keeping stresses on the spacecraft and any passengers within acceptable limits.[9] This may be accomplished by propulsive or aerodynamic (vehicle characteristics or parachute) means, or by some combination.

Entry vehicle shapes

[edit]There are several basic shapes used in designing entry vehicles:

Sphere or spherical section

[edit]

The simplest axisymmetric shape is the sphere or spherical section.[10] This can either be a complete sphere or a spherical section forebody with a converging conical afterbody. The aerodynamics of a sphere or spherical section are easy to model analytically using Newtonian impact theory. Likewise, the spherical section's heat flux can be accurately modeled with the Fay–Riddell equation.[11] The static stability of a spherical section is assured if the vehicle's center of mass is upstream from the center of curvature (dynamic stability is more problematic). Pure spheres have no lift. However, by flying at an angle of attack, a spherical section has modest aerodynamic lift thus providing some cross-range capability and widening its entry corridor. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, high-speed computers were not yet available and computational fluid dynamics was still embryonic. Because the spherical section was amenable to closed-form analysis, that geometry became the default for conservative design. Consequently, crewed capsules of that era were based upon the spherical section.

Pure spherical entry vehicles were used in the early Soviet Vostok and Voskhod capsules and in Soviet Mars and Venera descent vehicles. The Apollo command module used a spherical section forebody heat shield with a converging conical afterbody. It flew a lifting entry with a hypersonic trim angle of attack of −27° (0° is blunt-end first) to yield an average L/D (lift-to-drag ratio) of 0.368.[12] The resultant lift achieved a measure of cross-range control by offsetting the vehicle's center of mass from its axis of symmetry, allowing the lift force to be directed left or right by rolling the capsule on its longitudinal axis. Other examples of the spherical section geometry in crewed capsules are Soyuz/Zond, Gemini, and Mercury. Even these small amounts of lift allow trajectories that have very significant effects on peak g-force, reducing it from 8–9 g for a purely ballistic (slowed only by drag) trajectory to 4–5 g, as well as greatly reducing the peak reentry heat.[13]

Sphere-cone

[edit]The sphere-cone is a spherical section with a frustum or blunted cone attached. The sphere-cone's dynamic stability is typically better than that of a spherical section. The vehicle enters sphere-first. With a sufficiently small half-angle and properly placed center of mass, a sphere-cone can provide aerodynamic stability from Keplerian entry to surface impact. (The half-angle is the angle between the cone's axis of rotational symmetry and its outer surface, and thus half the angle made by the cone's surface edges.)

The original American sphere-cone aeroshell was the Mk-2 RV (reentry vehicle), which was developed in 1955 by the General Electric Corp. The Mk-2's design was derived from blunt-body theory and used a radiatively cooled thermal protection system (TPS) based upon a metallic heat shield (the different TPS types are later described in this article). The Mk-2 had significant defects as a weapon delivery system, i.e., it loitered too long in the upper atmosphere due to its lower ballistic coefficient and also trailed a stream of vaporized metal making it very visible to radar. These defects made the Mk-2 overly susceptible to anti-ballistic missile (ABM) systems. Consequently, an alternative sphere-cone RV to the Mk-2 was developed by General Electric.[citation needed]

This new RV was the Mk-6 which used a non-metallic ablative TPS, a nylon phenolic. This new TPS was so effective as a reentry heat shield that significantly reduced bluntness was possible.[citation needed] However, the Mk-6 was a huge RV with an entry mass of 3,360 kg, a length of 3.1 m and a half-angle of 12.5°. Subsequent advances in nuclear weapon and ablative TPS design allowed RVs to become significantly smaller with a further reduced bluntness ratio compared to the Mk-6. Since the 1960s, the sphere-cone has become the preferred geometry for modern ICBM RVs with typical half-angles being between 10° and 11°.[citation needed]

Reconnaissance satellite RVs (recovery vehicles) also used a sphere-cone shape and were the first American example of a non-munition entry vehicle (Discoverer-I, launched on 28 February 1959). The sphere-cone was later used for space exploration missions to other celestial bodies or for return from open space; e.g., Stardust probe. Unlike with military RVs, the advantage of the blunt body's lower TPS mass remained with space exploration entry vehicles like the Galileo Probe with a half-angle of 45° or the Viking aeroshell with a half-angle of 70°. Space exploration sphere-cone entry vehicles have landed on the surface or entered the atmospheres of Mars, Venus, Jupiter, and Titan.

Biconic

[edit]

The biconic is a sphere-cone with an additional frustum attached. The biconic offers a significantly improved L/D ratio. A biconic designed for Mars aerocapture typically has an L/D of approximately 1.0 compared to an L/D of 0.368 for the Apollo-CM. The higher L/D makes a biconic shape better suited for transporting people to Mars due to the lower peak deceleration. Arguably, the most significant biconic ever flown was the Advanced Maneuverable Reentry Vehicle (AMaRV). Four AMaRVs were made by the McDonnell Douglas Corp. and represented a significant leap in RV sophistication. Three AMaRVs were launched by Minuteman-1 ICBMs on 20 December 1979, 8 October 1980 and 4 October 1981. AMaRV had an entry mass of approximately 470 kg, a nose radius of 2.34 cm, a forward-frustum half-angle of 10.4°, an inter-frustum radius of 14.6 cm, aft-frustum half-angle of 6°, and an axial length of 2.079 meters. No accurate diagram or picture of AMaRV has ever appeared in the open literature. However, a schematic sketch of an AMaRV-like vehicle along with trajectory plots showing hairpin turns has been published.[14]

AMaRV's attitude was controlled through a split body flap (also called a split-windward flap) along with two yaw flaps mounted on the vehicle's sides. Hydraulic actuation was used for controlling the flaps. AMaRV was guided by a fully autonomous navigation system designed for evading anti-ballistic missile (ABM) interception. The McDonnell Douglas DC-X (also a biconic) was essentially a scaled-up version of AMaRV. AMaRV and the DC-X also served as the basis for an unsuccessful proposal for what eventually became the Lockheed Martin X-33.

Non-axisymmetric shapes

[edit]Non-axisymmetric shapes have been used for crewed entry vehicles. One example is the winged orbit vehicle that uses a delta wing for maneuvering during descent much like a conventional glider. This approach has been used by the American Space Shuttle, the Soviet Buran and the in-development Starship. The lifting body is another entry vehicle geometry and was used with the X-23 PRIME (Precision Recovery Including Maneuvering Entry) vehicle.[citation needed]

Entry heating

[edit]

Objects entering an atmosphere from space at high velocities relative to the atmosphere will cause very high levels of heating. Atmospheric entry heating comes principally from two sources:

- convection of hot gas flow past the surface of the body and catalytic chemical recombination reactions between the surface and atmospheric gases; and

- radiation from the energetic shock layer that forms in the front and sides of the body[15]

As velocity increases, both convective and radiative heating increase, but at different rates. At very high speeds, radiative heating will dominate the convective heat fluxes, as radiative heating is proportional to the eighth power of velocity, while convective heating is proportional to the third power of velocity. Radiative heating thus predominates early in atmospheric entry, while convection predominates in the later phases.[15]

During certain intensity of ionization, a radio-blackout with the spacecraft is produced.[16]

While NASA's Earth entry interface is at 400,000 feet (122 km), the main heating during controlled entry takes place at altitudes of 65 to 35 kilometres (213,000 to 115,000 ft), peaking at 58 kilometres (190,000 ft).[17]

Shock layer gas physics

[edit]At typical reentry temperatures, the air in the shock layer is both ionized and dissociated.[citation needed][18] This chemical dissociation necessitates various physical models to describe the shock layer's thermal and chemical properties. There are four basic physical models of a gas that are important to aeronautical engineers who design heat shields:

Perfect gas model

[edit]Almost all aeronautical engineers are taught the perfect (ideal) gas model during their undergraduate education. Most of the important perfect gas equations along with their corresponding tables and graphs are shown in NACA Report 1135.[19] Excerpts from NACA Report 1135 often appear in the appendices of thermodynamics textbooks and are familiar to most aeronautical engineers who design supersonic aircraft.

The perfect gas theory is elegant and extremely useful for designing aircraft but assumes that the gas is chemically inert. From the standpoint of aircraft design, air can be assumed to be inert for temperatures less than 550 K (277 °C; 530 °F) at one atmosphere pressure. The perfect gas theory begins to break down at 550 K and is not usable at temperatures greater than 2,000 K (1,730 °C; 3,140 °F). For temperatures greater than 2,000 K, a heat shield designer must use a real gas model.

Real (equilibrium) gas model

[edit]An entry vehicle's pitching moment can be significantly influenced by real-gas effects. Both the Apollo command module and the Space Shuttle were designed using incorrect pitching moments determined through inaccurate real-gas modelling. The Apollo-CM's trim-angle angle of attack was higher than originally estimated, resulting in a narrower lunar return entry corridor. The actual aerodynamic center of the Columbia was upstream from the calculated value due to real-gas effects. On Columbia's maiden flight (STS-1), astronauts John Young and Robert Crippen had some anxious moments during reentry when there was concern about losing control of the vehicle.[20]

An equilibrium real-gas model assumes that a gas is chemically reactive, but also assumes all chemical reactions have had time to complete and all components of the gas have the same temperature (this is called thermodynamic equilibrium). When air is processed by a shock wave, it is superheated by compression and chemically dissociates through many different reactions. Direct friction upon the reentry object is not the main cause of shock-layer heating. It is caused mainly from isentropic heating of the air molecules within the compression wave. Friction based entropy increases of the molecules within the wave also account for some heating.[original research?] The distance from the shock wave to the stagnation point on the entry vehicle's leading edge is called shock wave stand off. An approximate rule of thumb for shock wave standoff distance is 0.14 times the nose radius. One can estimate the time of travel for a gas molecule from the shock wave to the stagnation point by assuming a free stream velocity of 7.8 km/s and a nose radius of 1 meter, i.e., time of travel is about 18 microseconds. This is roughly the time required for shock-wave-initiated chemical dissociation to approach chemical equilibrium in a shock layer for a 7.8 km/s entry into air during peak heat flux. Consequently, as air approaches the entry vehicle's stagnation point, the air effectively reaches chemical equilibrium thus enabling an equilibrium model to be usable. For this case, most of the shock layer between the shock wave and leading edge of an entry vehicle is chemically reacting and not in a state of equilibrium. The Fay–Riddell equation,[11] which is of extreme importance towards modeling heat flux, owes its validity to the stagnation point being in chemical equilibrium. The time required for the shock layer gas to reach equilibrium is strongly dependent upon the shock layer's pressure. For example, in the case of the Galileo probe's entry into Jupiter's atmosphere, the shock layer was mostly in equilibrium during peak heat flux due to the very high pressures experienced (this is counterintuitive given the free stream velocity was 39 km/s during peak heat flux).

Determining the thermodynamic state of the stagnation point is more difficult under an equilibrium gas model than a perfect gas model. Under a perfect gas model, the ratio of specific heats (also called isentropic exponent, adiabatic index, gamma, or kappa) is assumed to be constant along with the gas constant. For a real gas, the ratio of specific heats can wildly oscillate as a function of temperature. Under a perfect gas model there is an elegant set of equations for determining thermodynamic state along a constant entropy stream line called the isentropic chain. For a real gas, the isentropic chain is unusable and a Mollier diagram would be used instead for manual calculation. However, graphical solution with a Mollier diagram is now considered obsolete with modern heat shield designers using computer programs based upon a digital lookup table (another form of Mollier diagram) or a chemistry based thermodynamics program. The chemical composition of a gas in equilibrium with fixed pressure and temperature can be determined through the Gibbs free energy method. Gibbs free energy is simply the total enthalpy of the gas minus its total entropy times temperature. A chemical equilibrium program normally does not require chemical formulas or reaction-rate equations. The program works by preserving the original elemental abundances specified for the gas and varying the different molecular combinations of the elements through numerical iteration until the lowest possible Gibbs free energy is calculated (a Newton–Raphson method is the usual numerical scheme). The data base for a Gibbs free energy program comes from spectroscopic data used in defining partition functions. Among the best equilibrium codes in existence is the program Chemical Equilibrium with Applications (CEA) which was written by Bonnie J. McBride and Sanford Gordon at NASA Lewis (now renamed "NASA Glenn Research Center"). Other names for CEA are the "Gordon and McBride Code" and the "Lewis Code". CEA is quite accurate up to 10,000 K for planetary atmospheric gases, but unusable beyond 20,000 K (double ionization is not modelled). CEA can be downloaded from the Internet along with full documentation and will compile on Linux under the G77 Fortran compiler.

Real (non-equilibrium) gas model

[edit]A non-equilibrium real gas model is the most accurate model of a shock layer's gas physics, but is more difficult to solve than an equilibrium model. The simplest non-equilibrium model is the Lighthill-Freeman model developed in 1958.[21][22] The Lighthill-Freeman model initially assumes a gas made up of a single diatomic species susceptible to only one chemical formula and its reverse; e.g., N2 = N + N and N + N = N2 (dissociation and recombination). Because of its simplicity, the Lighthill-Freeman model is a useful pedagogical tool, but is too simple for modelling non-equilibrium air. Air is typically assumed to have a mole fraction composition of 0.7812 molecular nitrogen, 0.2095 molecular oxygen and 0.0093 argon. The simplest real gas model for air is the five species model, which is based upon N2, O2, NO, N, and O. The five species model assumes no ionization and ignores trace species like carbon dioxide.

When running a Gibbs free energy equilibrium program,[clarification needed] the iterative process from the originally specified molecular composition to the final calculated equilibrium composition is essentially random and not time accurate. With a non-equilibrium program, the computation process is time accurate and follows a solution path dictated by chemical and reaction rate formulas. The five species model has 17 chemical formulas (34 when counting reverse formulas). The Lighthill-Freeman model is based upon a single ordinary differential equation and one algebraic equation. The five species model is based upon 5 ordinary differential equations and 17 algebraic equations.[citation needed] Because the 5 ordinary differential equations are tightly coupled, the system is numerically "stiff" and difficult to solve. The five species model is only usable for entry from low Earth orbit where entry velocity is approximately 7.8 km/s (28,000 km/h; 17,000 mph). For lunar return entry of 11 km/s,[23] the shock layer contains a significant amount of ionized nitrogen and oxygen. The five-species model is no longer accurate and a twelve-species model must be used instead. Atmospheric entry interface velocities on a Mars–Earth trajectory are on the order of 12 km/s (43,000 km/h; 27,000 mph).[24] Modeling high-speed Mars atmospheric entry—which involves a carbon dioxide, nitrogen and argon atmosphere—is even more complex requiring a 19-species model.[citation needed]

An important aspect of modelling non-equilibrium real gas effects is radiative heat flux. If a vehicle is entering an atmosphere at very high speed (hyperbolic trajectory, lunar return) and has a large nose radius then radiative heat flux can dominate TPS heating. Radiative heat flux during entry into an air or carbon dioxide atmosphere typically comes from asymmetric diatomic molecules; e.g., cyanogen (CN), carbon monoxide, nitric oxide (NO), single ionized molecular nitrogen etc. These molecules are formed by the shock wave dissociating ambient atmospheric gas followed by recombination within the shock layer into new molecular species. The newly formed diatomic molecules initially have a very high vibrational temperature that efficiently transforms the vibrational energy into radiant energy; i.e., radiative heat flux. The whole process takes place in less than a millisecond which makes modelling a challenge. The experimental measurement of radiative heat flux (typically done with shock tubes) along with theoretical calculation through the unsteady Schrödinger equation are among the more esoteric aspects of aerospace engineering. Most of the aerospace research work related to understanding radiative heat flux was done in the 1960s, but largely discontinued after conclusion of the Apollo Program. Radiative heat flux in air was just sufficiently understood to ensure Apollo's success. However, radiative heat flux in carbon dioxide (Mars entry) is still barely understood and will require major research.[citation needed]

Frozen gas model

[edit]The frozen gas model describes a special case of a gas that is not in equilibrium. The name "frozen gas" can be misleading. A frozen gas is not "frozen" like ice is frozen water. Rather a frozen gas is "frozen" in time (all chemical reactions are assumed to have stopped). Chemical reactions are normally driven by collisions between molecules. If gas pressure is slowly reduced such that chemical reactions can continue then the gas can remain in equilibrium. However, it is possible for gas pressure to be so suddenly reduced that almost all chemical reactions stop. For that situation the gas is considered frozen.[citation needed]

The distinction between equilibrium and frozen is important because it is possible for a gas such as air to have significantly different properties (speed-of-sound, viscosity etc.) for the same thermodynamic state; e.g., pressure and temperature. Frozen gas can be a significant issue in the wake behind an entry vehicle. During reentry, free stream air is compressed to high temperature and pressure by the entry vehicle's shock wave. Non-equilibrium air in the shock layer is then transported past the entry vehicle's leading side into a region of rapidly expanding flow that causes freezing. The frozen air can then be entrained into a trailing vortex behind the entry vehicle. Correctly modelling the flow in the wake of an entry vehicle is very difficult. Thermal protection shield (TPS) heating in the vehicle's afterbody is usually not very high, but the geometry and unsteadiness of the vehicle's wake can significantly influence aerodynamics (pitching moment) and particularly dynamic stability.[citation needed]

Thermal protection systems

[edit]A thermal protection system, or TPS, is the barrier that protects a spacecraft during the searing heat of atmospheric reentry. Multiple approaches for the thermal protection of spacecraft are in use, among them ablative heat shields, passive cooling, and active cooling of spacecraft surfaces. In general they can be divided into two categories: ablative TPS and reusable TPS.

Ablative TPS are required when space craft reach a relatively low altitude before slowing down.[dubious – discuss] Spacecraft like the space shuttle are designed to slow down at high altitude so that they can use reuseable TPS. (see: Space Shuttle thermal protection system).

Thermal protection systems are tested in high enthalpy ground testing or plasma wind tunnels that reproduce the combination of high enthalpy and high stagnation pressure using Induction plasma or DC plasma.

Ablative

[edit]

The ablative heat shield functions by lifting the hot shock layer gas away from the heat shield's outer wall (creating a cooler boundary layer). The boundary layer comes from blowing of gaseous reaction products from the heat shield material and provides protection against all forms of heat flux. The overall process of reducing the heat flux experienced by the heat shield's outer wall by way of a boundary layer is called blockage. Ablation occurs at two levels in an ablative TPS: the outer surface of the TPS material chars, melts, and sublimes, while the bulk of the TPS material undergoes pyrolysis and expels product gases. The gas produced by pyrolysis is what drives blowing and causes blockage of convective and catalytic heat flux. Pyrolysis can be measured in real time using thermogravimetric analysis, so that the ablative performance can be evaluated.[25] Ablation can also provide blockage against radiative heat flux by introducing carbon into the shock layer thus making it optically opaque. Radiative heat flux blockage was the primary thermal protection mechanism of the Galileo Probe TPS material (carbon phenolic).

Early research on ablation technology in the USA was centered at NASA's Ames Research Center located at Moffett Field, California. Ames Research Center was ideal, since it had numerous wind tunnels capable of generating varying wind velocities. Initial experiments typically mounted a mock-up of the ablative material to be analyzed within a hypersonic wind tunnel.[26] Testing of ablative materials occurs at the Ames Arc Jet Complex. Many spacecraft thermal protection systems have been tested in this facility, including the Apollo, space shuttle, and Orion heat shield materials.[27]

Carbon phenolic

[edit]Carbon phenolic was originally developed as a rocket nozzle throat material (used in the Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Booster) and for reentry-vehicle nose tips. The thermal conductivity of a particular TPS material is usually proportional to the material's density.[28] Carbon phenolic is a very effective ablative material, but also has high density which is undesirable.

The NASA Galileo Probe used carbon phenolic for its TPS material.[29]

If the heat flux experienced by an entry vehicle is insufficient to cause pyrolysis then the TPS material's conductivity could allow heat flux conduction into the TPS bondline material thus leading to TPS failure. Consequently, for entry trajectories causing lower heat flux, carbon phenolic is sometimes inappropriate and lower-density TPS materials such as the following examples can be better design choices:

Super light-weight ablator

[edit]SLA in SLA-561V stands for super light-weight ablator. SLA-561V is a proprietary ablative made by Lockheed Martin that has been used as the primary TPS material on all of the 70° sphere-cone entry vehicles sent by NASA to Mars other than the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL). SLA-561V begins significant ablation at a heat flux of approximately 110 W/cm2, but will fail for heat fluxes greater than 300 W/cm2. The MSL aeroshell TPS is currently designed to withstand a peak heat flux of 234 W/cm2. The peak heat flux experienced by the Viking 1 aeroshell which landed on Mars was 21 W/cm2. For Viking 1, the TPS acted as a charred thermal insulator and never experienced significant ablation. Viking 1 was the first Mars lander and based upon a very conservative design. The Viking aeroshell had a base diameter of 3.54 meters (the largest used on Mars until Mars Science Laboratory). SLA-561V is applied by packing the ablative material into a honeycomb core that is pre-bonded to the aeroshell's structure thus enabling construction of a large heat shield.[30]

Phenolic-impregnated carbon ablator

[edit]

Phenolic-impregnated carbon ablator (PICA), a carbon fiber preform impregnated in phenolic resin,[31] is a modern TPS material and has the advantages of low density (much lighter than carbon phenolic) coupled with efficient ablative ability at high heat flux. It is a good choice for ablative applications such as high-peak-heating conditions found on sample-return missions or lunar-return missions. PICA's thermal conductivity is lower than other high-heat-flux-ablative materials, such as conventional carbon phenolics.[citation needed]

PICA was patented by NASA Ames Research Center in the 1990s and was the primary TPS material for the Stardust aeroshell.[32] The Stardust sample-return capsule was the fastest man-made object ever to reenter Earth's atmosphere, at 28,000 mph (ca. 12.5 km/s) at 135 km altitude. This was faster than the Apollo mission capsules and 70% faster than the Shuttle.[1] PICA was critical for the viability of the Stardust mission, which returned to Earth in 2006. Stardust's heat shield (0.81 m base diameter) was made of one monolithic piece sized to withstand a nominal peak heating rate of 1.2 kW/cm2. A PICA heat shield was also used for the Mars Science Laboratory entry into the Martian atmosphere.[33]

PICA-X

[edit]An improved and easier to produce version called PICA-X was developed by SpaceX in 2006–2010[33] for the Dragon space capsule.[34] The first reentry test of a PICA-X heat shield was on the Dragon C1 mission on 8 December 2010.[35] The PICA-X heat shield was designed, developed and fully qualified by a small team of a dozen engineers and technicians in less than four years.[33] PICA-X is ten times less expensive to manufacture than the NASA PICA heat shield material.[36]

PICA-3

[edit]A second enhanced version of PICA—called PICA-3—was developed by SpaceX during the mid-2010s. It was first flight tested on the Crew Dragon spacecraft in 2019 during the flight demonstration mission, in April 2019, and put into regular service on that spacecraft in 2020.[37]

HARLEM

[edit]PICA and most other ablative TPS materials are either proprietary or classified, with formulations and manufacturing processes not disclosed in the open literature. This limits the ability of researchers to study these materials and hinders the development of thermal protection systems. Thus, the High Enthalpy Flow Diagnostics Group (HEFDiG) at the University of Stuttgart has developed an open carbon-phenolic ablative material, called the HEFDiG Ablation-Research Laboratory Experiment Material (HARLEM), from commercially available materials. HARLEM is prepared by impregnating a preform of a carbon fiber porous monolith (such as Calcarb rigid carbon insulation) with a solution of resole phenolic resin and polyvinylpyrrolidone in ethylene glycol, heating to polymerize the resin and then removing the solvent under vacuum. The resulting material is cured and machined to the desired shape.[38][39]

SIRCA

[edit]

Silicone-impregnated reusable ceramic ablator (SIRCA) was also developed at NASA Ames Research Center and was used on the Backshell Interface Plate (BIP) of the Mars Pathfinder and Mars Exploration Rover (MER) aeroshells. The BIP was at the attachment points between the aeroshell's backshell (also called the afterbody or aft cover) and the cruise ring (also called the cruise stage). SIRCA was also the primary TPS material for the unsuccessful Deep Space 2 (DS/2) Mars impactor probes with their 0.35-meter-base-diameter (1.1 ft) aeroshells. SIRCA is a monolithic, insulating material that can provide thermal protection through ablation. It is the only TPS material that can be machined to custom shapes and then applied directly to the spacecraft. There is no post-processing, heat treating, or additional coatings required (unlike Space Shuttle tiles). Since SIRCA can be machined to precise shapes, it can be applied as tiles, leading edge sections, full nose caps, or in any number of custom shapes or sizes. As of 1996[update], SIRCA had been demonstrated in backshell interface applications, but not yet as a forebody TPS material.[40]

AVCOAT

[edit]AVCOAT is a NASA-developed material used in the design of several ablative heat shields.[41]

NASA originally used it for the Apollo command module in the 1960s, and then utilized the material for its next-generation beyond low Earth orbit Orion crew module, which first flew in a December 2014 test and then operationally in November 2022.[42] The Avcoat to be used on Orion has been reformulated to meet environmental legislation that has been passed since the end of Apollo.[43][44]

Thermal soak

[edit]Thermal soak is a part of almost all TPS schemes. For example, an ablative heat shield loses most of its thermal protection effectiveness when the outer wall temperature drops below the minimum necessary for pyrolysis. From that time to the end of the heat pulse, heat from the shock layer convects into the heat shield's outer wall and would eventually conduct to the payload.[citation needed] This outcome can be prevented by ejecting the heat shield (with its heat soak) prior to the heat conducting to the inner wall.

Refractory insulation

[edit]

Refractory insulation keeps the heat in the outermost layer of the spacecraft surface, where it is conducted away by the air.[45] The temperature of the surface rises to incandescent levels, so the material must have a very high melting point, and the material must also exhibit very low thermal conductivity. Materials with these properties tend to be brittle, delicate, and difficult to fabricate in large sizes, so they are generally fabricated as relatively small tiles that are then attached to the structural skin of the spacecraft. There is a tradeoff between toughness and thermal conductivity: less conductive materials are generally more brittle. The space shuttle used multiple types of tiles. Tiles are also used on the Boeing X-37, Dream Chaser, and Starship's upper stage.

Because insulation cannot be perfect, some heat energy is stored in the insulation and in the underlying material ("thermal soaking") and must be dissipated after the spacecraft exits the high-temperature flight regime. Some of this heat will re-radiate through the surface or will be carried off the surface by convection, but some will heat the spacecraft structure and interior, which may require active cooling after landing.[45]

Typical Space Shuttle TPS tiles (LI-900) have remarkable thermal protection properties. An LI-900 tile exposed to a temperature of 1,000 K on one side will remain merely warm to the touch on the other side. However, they are relatively brittle and break easily, and cannot survive in-flight rain.[46]

Passively cooled

[edit]

In some early ballistic missile RVs (e.g., the Mk-2 and the sub-orbital Mercury spacecraft), radiatively cooled TPS were used to initially absorb heat flux during the heat pulse, and, then, after the heat pulse, radiate and convect the stored heat back into the atmosphere. However, the earlier version of this technique required a considerable quantity of metal TPS (e.g., titanium, beryllium, copper, etc.). Modern designers prefer to avoid this added mass by using ablative and thermal-soak TPS instead.

Thermal protection systems relying on emissivity use high emissivity coatings (HECs) to facilitate radiative cooling, while an underlying porous ceramic layer serves to protect the structure from high surface temperatures. High thermally stable emissivity values coupled with low thermal conductivity are key to the functionality of such systems.[47]

Radiatively cooled TPS can be found on modern entry vehicles, but reinforced carbon–carbon (RCC) (also called carbon–carbon) is normally used instead of metal. RCC was the TPS material on the Space Shuttle's nose cone and wing leading edges, and was also proposed as the leading-edge material for the X-33. Carbon is the most refractory material known, with a one-atmosphere sublimation temperature of 3,825 °C (6,917 °F) for graphite. This high temperature made carbon an obvious choice as a radiatively cooled TPS material. Disadvantages of RCC are that it is currently expensive to manufacture, is heavy, and lacks robust impact resistance.[48]

Some high-velocity aircraft, such as the SR-71 Blackbird and Concorde, deal with heating similar to that experienced by spacecraft, but at much lower intensity, and for hours at a time. Studies of the SR-71's titanium skin revealed that the metal structure was restored to its original strength through annealing due to aerodynamic heating. In the case of the Concorde, the aluminium nose was permitted to reach a maximum operating temperature of 127 °C (261 °F) (approximately 180 °C (324 °F) warmer than the normally sub-zero, ambient air); the metallurgical implications (loss of temper) that would be associated with a higher peak temperature were the most significant factors determining the top speed of the aircraft.

A radiatively cooled TPS for an entry vehicle is often called a hot-metal TPS. Early TPS designs for the Space Shuttle called for a hot-metal TPS based upon a nickel superalloy (dubbed René 41) and titanium shingles.[49] This Shuttle TPS concept was rejected, because it was believed a silica tile-based TPS would involve lower development and manufacturing costs.[citation needed] A nickel superalloy-shingle TPS was again proposed for the unsuccessful X-33 single-stage-to-orbit (SSTO) prototype.[50]

Recently, newer radiatively cooled TPS materials have been developed that could be superior to RCC. Known as Ultra-High Temperature Ceramics, they were developed for the prototype vehicle Slender Hypervelocity Aerothermodynamic Research Probe (SHARP). These TPS materials are based on zirconium diboride and hafnium diboride. SHARP TPS have suggested performance improvements allowing for sustained Mach 7 flight at sea level, Mach 11 flight at 100,000-foot (30,000 m) altitudes, and significant improvements for vehicles designed for continuous hypersonic flight. SHARP TPS materials enable sharp leading edges and nose cones to greatly reduce drag for airbreathing combined-cycle-propelled spaceplanes and lifting bodies. SHARP materials have exhibited effective TPS characteristics from zero to more than 2,000 °C (3,630 °F), with melting points over 3,500 °C (6,330 °F). They are structurally stronger than RCC, and, thus, do not require structural reinforcement with materials such as Inconel. SHARP materials are extremely efficient at reradiating absorbed heat, thus eliminating the need for additional TPS behind and between the SHARP materials and conventional vehicle structure. NASA initially funded (and discontinued) a multi-phase R&D program through the University of Montana in 2001 to test SHARP materials on test vehicles.[51][52]

Actively cooled

[edit]Various advanced reusable spacecraft and hypersonic aircraft designs have been proposed to employ heat shields made from temperature-resistant metal alloys that incorporate a refrigerant or cryogenic fuel circulating through them.

Such a TPS concept was proposed for the X-30 National Aerospace Plane (NASP) in the mid-80s.[citation needed] The NASP was supposed to have been a scramjet powered hypersonic aircraft, but failed in development.[citation needed]

In 2005 and 2012, two unmanned lifting body craft with actively cooled hulls were launched as a part of the German Sharp Edge Flight Experiment (SHEFEX).[citation needed]

In early 2019, SpaceX was developing an actively cooled heat shield for its Starship spacecraft where a part of the thermal protection system will be a transpirationally cooled outer-skin design for the reentering spaceship.[53][54] However, SpaceX abandoned this approach in favor of a modern version of heat shield tiles later in 2019.[55][56]

The Stoke Space Nova second stage, announced in October 2023 and not yet flying, uses a regeneratively cooled (by liquid hydrogen) heat shield.[57]

In the early 1960s various TPS systems were proposed to use water or other cooling liquid sprayed into the shock layer, or passed through channels in the heat shield. Advantages included the possibility of more all-metal designs which would be cheaper to develop, be more rugged, and eliminate the need for classified and unknown technology. The disadvantages are increased weight and complexity, and lower reliability. The concept has never been flown, but a similar technology (the plug nozzle[49]) did undergo extensive ground testing.

Propulsive entry

[edit]Fuel permitting, nothing prevents a vehicle from entering the atmosphere with a retrograde engine burn, which has the double effect of slowing the vehicle down much faster than atmospheric drag alone would, and forcing the compressed hot air away from the vehicle's body. During reentry, the first stage of the SpaceX Falcon 9 performs an entry burn to rapidly decelerate from its initial hypersonic speed.[citation needed]

High-drag suborbital entry

[edit]In 2004, aircraft designer Burt Rutan demonstrated the feasibility of a shape-changing airfoil for reentry with the sub-orbital SpaceShipOne. The wings on this craft rotate upward into the feathered configuration that provides a shuttlecock effect. Thus SpaceShipOne achieves much more aerodynamic drag on reentry while not experiencing significant thermal loads.

The configuration increases drag, as the craft is now less streamlined and results in more atmospheric gas particles hitting the spacecraft at higher altitudes than otherwise. The aircraft thus slows down more in higher atmospheric layers which is the key to efficient reentry. Secondly, the aircraft will automatically orient itself in this state to a high drag attitude.[58]

However, the velocity attained by SpaceShipOne prior to reentry is much lower than that of an orbital spacecraft, and engineers, including Rutan, recognize that a feathered reentry technique is not suitable for return from orbit.

On 4 May 2011, the first test on the SpaceShipTwo of the feathering mechanism was made during a glideflight after release from the White Knight Two. Premature deployment of the feathering system was responsible for the 2014 VSS Enterprise crash, in which the aircraft disintegrated, killing the co-pilot.

The feathered reentry was first described by Dean Chapman of NACA in 1958.[59] In the section of his report on Composite Entry, Chapman described a solution to the problem using a high-drag device:

It may be desirable to combine lifting and nonlifting entry in order to achieve some advantages... For landing maneuverability it obviously is advantageous to employ a lifting vehicle. The total heat absorbed by a lifting vehicle, however, is much higher than for a nonlifting vehicle... Nonlifting vehicles can more easily be constructed... by employing, for example, a large, light drag device... The larger the device, the smaller is the heating rate.

Nonlifting vehicles with shuttlecock stability are advantageous also from the viewpoint of minimum control requirements during entry.

... an evident composite type of entry, which combines some of the desirable features of lifting and nonlifting trajectories, would be to enter first without lift but with a... drag device; then, when the velocity is reduced to a certain value... the device is jettisoned or retracted, leaving a lifting vehicle... for the remainder of the descent.

Inflatable heat shield entry

[edit]Deceleration for atmospheric reentry, especially for higher-speed Mars-return missions, benefits from maximizing "the drag area of the entry system. The larger the diameter of the aeroshell, the bigger the payload can be."[60] An inflatable aeroshell provides one alternative for enlarging the drag area with a low-mass design.

Russia

[edit]Such an inflatable shield/aerobrake was designed for the penetrators of Mars 96 mission. Since the mission failed due to the launcher malfunction, the NPO Lavochkin and DASA/ESA have designed a mission for Earth orbit. The Inflatable Reentry and Descent Technology (IRDT) demonstrator was launched on Soyuz-Fregat on 8 February 2000. The inflatable shield was designed as a cone with two stages of inflation. Although the second stage of the shield failed to inflate, the demonstrator survived the orbital reentry and was recovered.[61][62] The subsequent missions flown on the Volna rocket failed due to launcher failure.[63]

NASA IRVE

[edit]

NASA launched an inflatable heat shield experimental spacecraft on 17 August 2009 with the successful first test flight of the Inflatable Re-entry Vehicle Experiment (IRVE). The heat shield had been vacuum-packed into a 15-inch-diameter (38 cm) payload shroud and launched on a Black Brant 9 sounding rocket from NASA's Wallops Flight Facility on Wallops Island, Virginia. "Nitrogen inflated the 10-foot-diameter (3.0 m) heat shield, made of several layers of silicone-coated [Kevlar] fabric, to a mushroom shape in space several minutes after liftoff."[60] The rocket apogee was at an altitude of 131 miles (211 km) where it began its descent to supersonic speed. Less than a minute later the shield was released from its cover to inflate at an altitude of 124 miles (200 km). The inflation of the shield took less than 90 seconds.[60]

NASA HIAD

[edit]Following the success of the initial IRVE experiments, NASA developed the concept into the more ambitious Hypersonic Inflatable Aerodynamic Decelerator (HIAD). The current design is shaped like a shallow cone, with the structure built up as a stack of circular inflated tubes of gradually increasing major diameter. The forward (convex) face of the cone is covered with a flexible thermal protection system robust enough to withstand the stresses of atmospheric entry (or reentry).[64][65]

In 2012, a HIAD was tested as Inflatable Reentry Vehicle Experiment 3 (IRVE-3) using a sub-orbital sounding rocket, and worked.[66]: 8

See also Low-Density Supersonic Decelerator, a NASA project with tests in 2014 and 2015 of a 6 m diameter SIAD-R.

LOFTID

[edit]

A 6-meter (20 ft) inflatable reentry vehicle, Low-Earth Orbit Flight Test of an Inflatable Decelerator (LOFTID),[67] was launched in November 2022, inflated in orbit, reentered faster than Mach 25, and was successfully recovered on November 10.

Entry vehicle design considerations

[edit]There are four critical parameters considered when designing a vehicle for atmospheric entry:[68]

- Peak heat flux

- Heat load

- Peak deceleration

- Peak dynamic pressure

Peak heat flux and dynamic pressure selects the TPS material. Heat load selects the thickness of the TPS material stack. Peak deceleration is of major importance for crewed missions. The upper limit for crewed return to Earth from low Earth orbit (LEO) or lunar return is 10g.[69] For Martian atmospheric entry after long exposure to zero gravity, the upper limit is 4g.[69] Peak dynamic pressure can also influence the selection of the outermost TPS material if spallation is an issue. The reentry vehicle's design parameters may be assessed through numerical simulation, including simplifications of the vehicle's dynamics, such as the planar reentry equations and heat flux correlations.[70]

Starting from the principle of conservative design, the engineer typically considers two worst-case trajectories, the undershoot and overshoot trajectories. The overshoot trajectory is typically defined as the shallowest-allowable entry velocity angle prior to atmospheric skip-off. The overshoot trajectory has the highest heat load and sets the TPS thickness. The undershoot trajectory is defined by the steepest allowable trajectory. For crewed missions the steepest entry angle is limited by the peak deceleration. The undershoot trajectory also has the highest peak heat flux and dynamic pressure. Consequently, the undershoot trajectory is the basis for selecting the TPS material. There is no "one size fits all" TPS material. A TPS material that is ideal for high heat flux may be too conductive (too dense) for a long duration heat load. A low-density TPS material might lack the tensile strength to resist spallation if the dynamic pressure is too high. A TPS material can perform well for a specific peak heat flux, but fail catastrophically for the same peak heat flux if the wall pressure is significantly increased (this happened with NASA's R-4 test spacecraft).[69] Older TPS materials tend to be more labor-intensive and expensive to manufacture compared to modern materials. However, modern TPS materials often lack the flight history of the older materials (an important consideration for a risk-averse designer).

Based upon Allen and Eggers discovery, maximum aeroshell bluntness (maximum drag) yields minimum TPS mass. Maximum bluntness (minimum ballistic coefficient) also yields a minimal terminal velocity at maximum altitude (very important for Mars EDL, but detrimental for military RVs). However, there is an upper limit to bluntness imposed by aerodynamic stability considerations based upon shock wave detachment. A shock wave will remain attached to the tip of a sharp cone if the cone's half-angle is below a critical value. This critical half-angle can be estimated using perfect gas theory (this specific aerodynamic instability occurs below hypersonic speeds). For a nitrogen atmosphere (Earth or Titan), the maximum allowed half-angle is approximately 60°. For a carbon dioxide atmosphere (Mars or Venus), the maximum-allowed half-angle is approximately 70°. After shock wave detachment, an entry vehicle must carry significantly more shocklayer gas around the leading edge stagnation point (the subsonic cap). Consequently, the aerodynamic center moves upstream thus causing aerodynamic instability. It is incorrect to reapply an aeroshell design intended for Titan entry (Huygens probe in a nitrogen atmosphere) for Mars entry (Beagle 2 in a carbon dioxide atmosphere).[citation needed][original research?] Prior to being abandoned, the Soviet Mars lander program achieved one successful landing (Mars 3), on the second of three entry attempts (the others were Mars 2 and Mars 6). The Soviet Mars landers were based upon a 60° half-angle aeroshell design.

A 45° half-angle sphere-cone is typically used for atmospheric probes (surface landing not intended) even though TPS mass is not minimized. The rationale for a 45° half-angle is to have either aerodynamic stability from entry-to-impact (the heat shield is not jettisoned) or a short-and-sharp heat pulse followed by prompt heat shield jettison. A 45° sphere-cone design was used with the DS/2 Mars impactor and Pioneer Venus probes.

Atmospheric entry accidents

[edit]

- Friction with air

- In air flight

- Expulsion lower angle

- Perpendicular to the entry point

- Excess friction 6.9° to 90°

- Repulsion of 5.5° or less

- Explosion friction

- Plane tangential to the entry point

Not all atmospheric reentries have been completely successful:

- Voskhod 2 – The service module failed to detach for some time, but the crew survived.

- Soyuz 5 – The service module failed to detach, but the crew survived.

- Apollo 15 - One of the three ringsail parachutes failed during the ocean landing, likely damaged as the spacecraft vented excess control fuel. The spacecraft was designed to land safely with only two parachutes, and the crew were uninjured.

- Mars Polar Lander – Failed during EDL. The failure was believed to be the consequence of a software error. The precise cause is unknown for lack of real-time telemetry.

- Space Shuttle Columbia STS-1 – a combination of launch damage, protruding gap filler, and tile installation error resulted in serious damage to the orbiter, only some of which the crew was aware. Had the crew known the extent of the damage before attempting reentry, they would have flown the shuttle to a safe altitude and then bailed out. Nevertheless, reentry was successful, and the orbiter proceeded to a normal landing.

- Space Shuttle Atlantis STS-27 – Insulation from the starboard solid rocket booster nose cap struck the orbiter during launch, causing significant tile damage. This dislodged one tile completely, over an aluminum mounting plate for a TACAN antenna. The antenna sustained extreme heat damage, but prevented the hot gas from penetrating the vehicle body.

- Genesis – The parachute failed to deploy due to a G-switch having been installed backwards (a similar error delayed parachute deployment for the Galileo Probe). Consequently, the Genesis entry vehicle crashed into the desert floor. The payload was damaged, but most scientific data were recoverable.

- Soyuz TMA-11 – The Soyuz propulsion module failed to separate properly; fallback ballistic reentry was executed that subjected the crew to accelerations of about 8 standard gravities (78 m/s2).[71] The crew survived.

- Starship IFT-3: The SpaceX Starship's third integrated test flight was supposed to end with a hard splashdown in the Indian Ocean. However, approximately 48.5 minutes after launch, at an altitude of 65km, contact with the spacecraft was lost, indicating that it burned up on reentry. This was caused by excessive vehicle rolling due to clogged vents on the vehicle.[72]

- Starship IFT-9- IFT 9 was going to end with a soft splashdown off the west coast of Australia but a fuel leak in the main tank after second engine cutoff led to a failure of the reaction control system and thus the payload deployment test and an in space burn was aborted and Starship broke up at approximately T+46:48 after launch.

Some reentries have resulted in significant disasters:

- Soyuz 1 – The attitude control system failed while still in orbit and later parachutes got entangled during the emergency landing sequence (entry, descent, and landing (EDL) failure). Lone cosmonaut Vladimir Mikhailovich Komarov died.

- Soyuz 11 – During tri-module separation, a valve seal was opened by the shock, depressurizing the descent module; the crew of three asphyxiated in space minutes before reentry.

- Space Shuttle Columbia STS-107 – The failure of a reinforced carbon–carbon panel on a wing leading edge caused by debris impact at launch led to breakup of the orbiter on reentry resulting in the deaths of all seven crew members.

Uncontrolled and unprotected entries

[edit]Of satellites that reenter, approximately 10–40% of the mass of the object may reach the surface of the Earth.[73] On average, about one catalogued object reentered per day as of 2014[update].[74]

Because the Earth's surface is predominantly water, most objects that survive reentry land in one of the world's oceans. The estimated chance that a given person would get hit and injured during their lifetime is around 1 in a trillion.[75]

On January 24, 1978, the Soviet Kosmos 954 (3,800 kilograms [8,400 lb]) reentered and crashed near Great Slave Lake in the Northwest Territories of Canada. The satellite was nuclear-powered and left radioactive debris near its impact site.[76]

On July 11, 1979, the US Skylab space station (77,100 kilograms [170,000 lb]) reentered and spread debris across the Australian Outback.[77] The reentry was a major media event largely due to the Cosmos 954 incident, but not viewed as much as a potential disaster since it did not carry toxic nuclear or hydrazine fuel. NASA had originally hoped to use a Space Shuttle mission to either extend its life or enable a controlled reentry, but delays in the Shuttle program, plus unexpectedly high solar activity, made this impossible.[78][79]

On February 7, 1991, the Soviet Salyut 7 space station (19,820 kilograms [43,700 lb]), with the Kosmos 1686 module (20,000 kilograms [44,000 lb]) attached, reentered and scattered debris over the town of Capitán Bermúdez, Argentina.[80][49][81] The station had been boosted to a higher orbit in August 1986 in an attempt to keep it up until 1994, but in a scenario similar to Skylab, the planned Buran shuttle was cancelled and high solar activity caused it to come down sooner than expected.

On September 7, 2011, NASA announced the impending uncontrolled reentry of the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (6,540 kilograms [14,420 lb]) and noted that there was a small risk to the public.[82] The decommissioned satellite reentered the atmosphere on September 24, 2011, and some pieces are presumed to have crashed into the South Pacific Ocean over a debris field 500 miles (800 km) long.[83]

On April 1, 2018, the Chinese Tiangong-1 space station (8,510 kilograms [18,760 lb]) reentered over the Pacific Ocean, halfway between Australia and South America.[84] The China Manned Space Engineering Office had intended to control the reentry, but lost telemetry and control in March 2017.[85]

On May 11, 2020, the core stage of Chinese Long March 5B (COSPAR ID 2020-027C) weighing roughly 20,000 kilograms [44,000 lb]) made an uncontrolled reentry over the Atlantic Ocean, near West African coast.[86][87] Few pieces of rocket debris reportedly survived reentry and fell over at least two villages in Ivory Coast.[88][89]

On May 8, 2021, the core stage of Chinese Long March 5B (COSPAR ID 2021-0035B) weighing 23,000 kilograms [51,000 lb]) made an uncontrolled reentry, just west of the Maldives in the Indian Ocean (approximately 72.47°E longitude and 2.65°N latitude).[90] Witnesses reported rocket debris as far away as the Arabian peninsula.[91]

Deorbit disposal

[edit]Salyut 1, the world's first space station, was deliberately de-orbited into the Pacific Ocean in 1971 following the Soyuz 11 accident. Its successor, Salyut 6, was de-orbited in a controlled manner as well.

On June 4, 2000, the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory was deliberately de-orbited after one of its gyroscopes failed. The debris that did not burn up fell harmlessly into the Pacific Ocean. The observatory was still operational, but the failure of another gyroscope would have made de-orbiting much more difficult and dangerous. With some controversy, NASA decided in the interest of public safety that a controlled crash was preferable to letting the craft come down at random.

In 2001, the Russian Mir space station was deliberately de-orbited, and broke apart in the fashion expected by the command center during atmospheric reentry. Mir entered the Earth's atmosphere on March 23, 2001, near Nadi, Fiji, and fell into the South Pacific Ocean.

On February 21, 2008, a disabled U.S. spy satellite, USA-193, was hit at an altitude of approximately 246 kilometers (153 mi) with an SM-3 missile fired from the U.S. Navy cruiser Lake Erie off the coast of Hawaii. The satellite was inoperative, having failed to reach its intended orbit when it was launched in 2006. Due to its rapidly deteriorating orbit it was destined for uncontrolled reentry within a month. U.S. Department of Defense expressed concern that the 1,000-pound (450 kg) fuel tank containing highly toxic hydrazine might survive reentry to reach the Earth's surface intact. Several governments including those of Russia, China, and Belarus protested the action as a thinly veiled demonstration of US anti-satellite capabilities.[92] China had previously caused an international incident when it tested an anti-satellite missile in 2007.

-

Closeup of Gemini 2 heat shield

-

Cross section of Gemini 2 heat shield

Environmental impact

[edit]

Atmospheric entry has a measurable impact on Earth's atmosphere, particularly the stratosphere.

Atmospheric entry by spacecrafts accounted for 3% of all atmospheric entries by 2021, but in a scenario in which the number of satellites since 2019 are doubled, artificial entries would make 40% of all entries,[93] which would cause atmospheric aerosols to be 94% artificial.[94] The impact of spacecrafts burning up in the atmosphere during artificial atmospheric entry is different to meteors due to the spacecrafts' generally larger size and different composition. The atmospheric pollutants produced by artificial atmospheric burning-up have been traced in the atmosphere and identified as reacting and possibly negatively impacting the composition of the atmosphere and particularly the ozone layer.[93]

Considering space sustainability in regard to atmospheric impact of re-entry is by 2022 just developing[95] and has been identified in 2024 as suffering from "atmosphere-blindness", causing global environmental injustice.[96] This is identified as a result of the current end-of life spacecraft management, which favors the station keeping practice of controlled re-entry.[96] This is mainly done to prevent the dangers from uncontrolled atmospheric entries and space debris.[96]

Suggested alternatives are the use of less polluting materials and by in-orbit servicing and potentially in-space recycling.[95][96]

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]- Van Allen radiation belt – Zone of energetic charged particles around the planet Earth

- Aerocapture – Orbital transfer maneuver

- Decelerated micrometeorites – Small particles between planets

- Ionization blackout – Halt to communication abilities or utilization

- Intercontinental ballistic missile – Ballistic missile with a range of more than 5,500 kilometres

- Lander (spacecraft) – Type of spacecraft

- Landing footprint

- List of reentering space debris

- Skip reentry – Glide and reentry mechanisms that use aerodynamic lift in the upper atmosphere

- Space capsule – Type of spacecraft

- Space Shuttle thermal protection system – Space Shuttle heat shielding system

- Paper plane launched from space

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Stardust – Cool Facts". stardust.jpl.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on January 12, 2010. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ "ATO: Airship To Orbit" (PDF). JP Aerospace. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ Gross, F. (1965). "Buoyant Probes into the Venus Atmosphere". Unmanned Spacecraft Meeting 1965. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. doi:10.2514/6.1965-1407.

- ^ Goddard, Robert H. (March 1920). "Report Concerning Further Developments". The Smithsonian Institution Archives. Archived from the original on June 26, 2009. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- ^ Boris Chertok, "Rockets and People", NASA History Series, 2006

- ^ Hansen, James R. (June 1987). "Chapter 12: Hypersonics and the Transition to Space". Engineer in Charge: A History of the Langley Aeronautical Laboratory, 1917–1958. The NASA History Series. Vol. sp-4305. United States Government Printing. ISBN 978-0-318-23455-7. Archived from the original on July 14, 2019. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- ^ Allen, H. Julian; Eggers, A. J. Jr. (1958). "A Study of the Motion and Aerodynamic Heating of Ballistic Missiles Entering the Earth's Atmosphere at High Supersonic Speeds" (PDF). NACA Annual Report. 44.2 (NACA-TR-1381). NASA Technical Reports: 1125–1140. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2015.

- ^ "NASA.gov" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Graves, Claude A.; Harpold, Jon C. (March 1972). Apollo Experience Report – Mission Planning for Apollo Entry (PDF). NASA Technical Note (TN) D-6725. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 25, 2019. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

The purpose of the Apollo entry maneuver is to dissipate the energy of a spacecraft traveling at high speed through the atmosphere of the earth so that the flight crew, their equipment, and their cargo are returned safely to a preselected location on the surface of the earth. This purpose must be accomplished while stresses on both the spacecraft and the flight crew are maintained within acceptable limits.

- ^ Przadka, W.; Miedzik, J.; Goujon-Durand, S.; Wesfreid, J.E. "The wake behind the sphere; analysis of vortices during transition from steadiness to unsteadiness" (PDF). Polish french cooperation in fluid research. Archive of Mechanics., 60, 6, pp. 467–474, Warszawa 2008. Received May 29, 2008; revised version November 13, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved April 3, 2015.

- ^ a b Fay, J. A.; Riddell, F. R. (February 1958). "Theory of Stagnation Point Heat Transfer in Dissociated Air" (PDF). Journal of the Aeronautical Sciences. 25 (2): 73–85. doi:10.2514/8.7517. Archived from the original (PDF Reprint) on January 7, 2005. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

- ^ "Hillje, Ernest R., "Entry Aerodynamics at Lunar Return Conditions Obtained from the Flight of Apollo 4 (AS-501)," NASA TN D-5399, (1969)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Whittington, Kurt Thomas (April 11, 2011). A Tool to Extrapolate Thermal Reentry Atmosphere Parameters Along a Body in Trajectory Space (PDF). NCSU Libraries Technical Reports Repository (Report). A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Aerospace Engineering Raleigh, North Carolina 2011, pp.5. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ Regan, Frank J. and Anadakrishnan, Satya M., "Dynamics of Atmospheric Re-Entry", AIAA Education Series, American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc., New York, ISBN 1-56347-048-9, doi:10.2514/4.861741, (1993).

- ^ a b Johnson, Sylvia M.; Squire, Thomas H.; Lawson, John W.; Gusman, Michael; Lau, K-H; Sanjuro, Angel (January 30, 2014). Biologically-Derived Photonic Materials for Thermal Protection Systems (PDF). 38th Annual Conference on Composites, Materials, and Structures January 27–30, 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 1, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ Poddar, Shashi; Sharma, Deewakar (2015). "Blackout mitigation during space vehicle re-entry". Optik. 126 (24). Elsevier BV: 5899–5902. Bibcode:2015Optik.126.5899P. doi:10.1016/j.ijleo.2015.09.141. ISSN 0030-4026.

- ^ Di Fiore, Francesco; Maggiore, Paolo; Mainini, Laura (October 4, 2021). "Multifidelity domain-aware learning for the design of re-entry vehicles". Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization. 64 (5). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 3017–3035. doi:10.1007/s00158-021-03037-4. ISSN 1615-147X. S2CID 244179568.

- ^ "Ionization And Dissociation Effects On Hypersonic Boundary-Layer Stability" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 1, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ "Equations, tables, and charts for compressible flow" (PDF). NACA Annual Report. 39 (NACA-TR-1135). NASA Technical Reports: 613–681. 1953. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ Kenneth Iliff and Mary Shafer, Space Shuttle Hypersonic Aerodynamic and Aerothermodynamic Flight Research and the Comparison to Ground Test Results, pp. 5–6 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Lighthill, M.J. (January 1957). "Dynamics of a Dissociating Gas. Part I. Equilibrium Flow". Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 2 (1): 1–32. Bibcode:1957JFM.....2....1L. doi:10.1017/S0022112057000713. S2CID 120442951.

- ^ Freeman, N.C. (August 1958). "Non-equilibrium Flow of an Ideal Dissociating Gas". Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 4 (4): 407–425. Bibcode:1958JFM.....4..407F. doi:10.1017/S0022112058000549. S2CID 122671767.

- ^ Entry Aerodynamics at Lunar Return Conditions Obtained from the Fliigh of Apollo 4 Archived April 11, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Ernest R. Hillje, NASA, TN: D-5399, accessed 29 December 2018.

- ^ Overview of the Mars Sample Return Earth Entry Vehicle Archived December 1, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, NASA, accessed 29 December 2018.

- ^ Parker, John and C. Michael Hogan, "Techniques for Wind Tunnel assessment of Ablative Materials", NASA Ames Research Center, Technical Publication, August, 1965.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael, Parker, John and Winkler, Ernest, of NASA Ames Research Center, "An Analytical Method for Obtaining the Thermogravimetric Kinetics of Char-forming Ablative Materials from Thermogravimetric Measurements", AIAA/ASME Seventh Structures and Materials Conference, April, 1966

- ^ "Arc Jet Complex". www.nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on October 5, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2015.

- ^ Di Benedetto, A.T.; Nicolais, L.; Watanabe, R. (1992). Composite materials : proceedings of Symposium A4 on Composite Materials of the International Conference on Advanced Materials – ICAM 91, Strasbourg, France, 27–29 May 1991. Amsterdam: North-Holland. p. 111. ISBN 978-0444893567.

- ^ Milos, Frank S. (1997). "Galileo Probe Heat Shield Ablation Experiment". Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets. 34 (6): 705–713. Bibcode:1997JSpRo..34..705M. doi:10.2514/2.3293. ISSN 1533-6794.

- ^ Tran, Huy; Michael Tauber; William Henline; Duoc Tran; Alan Cartledge; Frank Hui; Norm Zimmerman (1996). Ames Research Center Shear Tests of SLA-561V Heat Shield Material for Mars-Pathfinder (PDF) (Technical report). NASA Ames Research Center. NASA Technical Memorandum 110402. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ Lachaud, Jean; N. Mansour, Nagi (June 2010). A pyrolysis and ablation toolbox based on OpenFOAM (PDF). 5th OpenFOAM Workshop. Gothenburg, Sweden. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ^ Tran, Huy K, et al., "Qualification of the forebody heat shield of the Stardust's Sample Return Capsule", AIAA, Thermophysics Conference, 32nd, Atlanta, GA; 23–25 June 1997.

- ^ a b c

Chambers, Andrew; Dan Rasky (November 14, 2010). "NASA + SpaceX Work Together". NASA. Archived from the original on April 16, 2011. Retrieved February 16, 2011.

SpaceX undertook the design and manufacture of the reentry heat shield; it brought speed and efficiency that allowed the heat shield to be designed, developed, and qualified in less than four years.'

- ^ "SpaceX Manufactured Heat Shield Material Passes High Temperature Tests Simulating Reentry Heating Conditions of Dragon Spacecraft". www.spaceref.com. February 23, 2009.

- ^ Dragon could visit space station next, msnbc.com, 2010-12-08, accessed 2010-12-09.

- ^ Chaikin, Andrew (January 2012). "1 visionary + 3 launchers + 1,500 employees = ? : Is SpaceX changing the rocket equation?". Air & Space Smithsonian. Archived from the original on September 7, 2018. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

SpaceX's material, called PICA-X, is one-tenth as expensive than the original [NASA PICA material and is better], ... a single PICA-X heat shield could withstand hundreds of returns from low Earth orbit; it can also handle the much higher energy reentries from the Moon or Mars.

- ^ NASA TV broadcast for the Crew Dragon Demo-2 mission departure from the ISS Archived August 2, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, NASA, 1 August 2020.

- ^ Poloni, E.; Grigat, F.; Eberhart, M.; et al. (August 12, 2023). "An open carbon–phenolic ablator for scientific exploration". Scientific Reports. 13 (1) 13135: 13135. Bibcode:2023NatSR..1313135P. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-40351-x. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 10423272. PMID 37573464.

- ^ Poloni, E.; et al. (2022). "Carbon ablators with porosity tailored for aerospace thermal protection during atmospheric re-entry". Carbon. 195: 80–91. arXiv:2110.04244. Bibcode:2022Carbo.195...80P. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2022.03.062. ISSN 0008-6223.

- ^ Tran, Huy K., et al., "Silicone impregnated reusable ceramic ablators for Mars follow-on missions," AIAA-1996-1819, Thermophysics Conference, 31st, New Orleans, June 17–20, 1996.

- ^ Flight-Test Analysis Of Apollo Heat-Shield Material Using The Pacemaker Vehicle System Archived September 25, 2020, at the Wayback Machine NASA Technical Note D-4713, pp. 8, 1968–08, accessed 2010-12-26. "Avcoat 5026-39/HC-G is an epoxy novolac resin with special additives in a fiberglass honeycomb matrix. In fabrication, the empty honeycomb is bonded to the primary structure and the resin is gunned into each cell individually. ... The overall density of the material is 32 lb/ft3 (512 kg/m3). The char of the material is composed mainly of silica and carbon. It is necessary to know the amounts of each in the char because in the ablation analysis the silica is considered to be inert, but the carbon is considered to enter into exothermic reactions with oxygen. ... At 2160O R (12000 K), 54 percent by weight of the virgin material has volatilized and 46 percent has remained as char. ... In the virgin material, 25 percent by weight is silica, and since the silica is considered to be inert the char-layer composition becomes 6.7 lb/ft3 (107.4 kg/m3) of carbon and 8 lb/ft3 (128.1 kg/m3) of silica."

- ^ NASA.gov NASA Selects Material for Orion Spacecraft Heat Shield Archived November 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, 2009-04-07, accessed 2011-01-02.

- ^ "Flightglobal.com NASA's Orion heat shield decision expected this month 2009-10-03, accessed 2011-01-02". Archived from the original on March 24, 2009. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ^ "Company Watch – NASA. – Free Online Library". www.thefreelibrary.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2011.

- ^ a b Johnson, Sylvia M. (January 25, 2015). Thermal Protection Systems: Past, Present and Future. International Conference and Exposition on Advanced Ceramics and Composites (Daytona Beach, FL). ARC-E-DAA-TN29151. Archived from the original on September 5, 2021. Retrieved September 5, 2021.

- ^ https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19880011857/downloads/19880011857.pdf Damage testing on effect of Rain by Robert R. Meyer and Jack Barneburg

- ^ Shao, Gaofeng; et al. (2019). "Improved oxidation resistance of high emissivity coatings on fibrous ceramic for reusable space systems". Corrosion Science. 146: 233–246. arXiv:1902.03943. Bibcode:2019Corro.146..233S. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2018.11.006. S2CID 118927116.

- ^ "Columbia Accident Investigation Board". history.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on December 25, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Space Shuttle". www.astronautix.com. Archived from the original on March 18, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ "X-33 Heat Shield Development report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

- ^ "SHARP Reentry Vehicle Prototype" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 15, 2005. Retrieved April 9, 2006.

- ^ "sharp structure homepage w left". Archived from the original on October 16, 2015.

- ^ Why Elon Musk Turned to Stainless Steel for SpaceX's Starship Mars Rocket Archived February 3, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Mike Wall, space.com, 23 January 2019, accessed 23 March 2019.

- ^ SpaceX CEO Elon Musk explains Starship's "transpiring" steel heat shield in Q&A Archived January 24, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Eric Ralph, Teslarati News, 23 January 2019, accessed 23 March 2019

- ^ Musk, Elon [@elonmusk] (September 24, 2019). "@OranMaliphant @Erdayastronaut Could do it, but we developed low cost reusable tiles that are much lighter than transpiration cooling & quite robust" (Tweet). Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2021 – via Twitter.