Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Atmosphere of Earth

View on Wikipedia

The atmosphere of Earth consists of a layer of mixed gas (commonly referred to as air) that is retained by gravity, surrounding the Earth's surface. It contains variable quantities of suspended aerosols and particulates that create weather features such as clouds and hazes. The atmosphere serves as a protective buffer between the Earth's surface and outer space. It shields the surface from most meteoroids and ultraviolet solar radiation, reduces diurnal temperature variation – the temperature extremes between day and night, and keeps it warm through heat retention via the greenhouse effect. The atmosphere redistributes heat and moisture among different regions via air currents, and provides the chemical and climate conditions that allow life to exist and evolve on Earth.

By mole fraction (i.e., by quantity of molecules), dry air contains 78.08% nitrogen, 20.95% oxygen, 0.93% argon, 0.04% carbon dioxide, and small amounts of other trace gases (see Composition below for more detail). Air also contains a variable amount of water vapor, on average around 1% at sea level, and 0.4% over the entire atmosphere.

Earth's primordial atmosphere consisted of gases accreted from the solar nebula, but the composition changed significantly over time, affected by many factors such as volcanism, outgassing, impact events, weathering and the evolution of life (particularly the photoautotrophs). In the present day, human activity has contributed to atmospheric changes, such as climate change (mainly through deforestation and fossil-fuel–related global warming), ozone depletion and acid deposition.

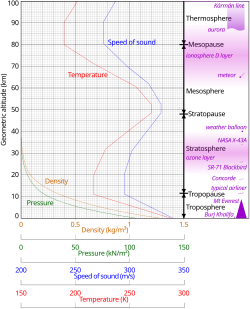

The atmosphere has a mass of about 5.15×1018 kg,[2] three quarters of which is within about 11 km (6.8 mi; 36,000 ft) of the surface. The atmosphere becomes thinner with increasing altitude, with no definite boundary between the atmosphere and outer space. The Kármán line at 100 km (62 mi) is often used as a conventional definition of the edge of space. Several layers can be distinguished in the atmosphere based on characteristics such as temperature and composition, namely the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere (formally the ionosphere), and exosphere. Air composition, temperature and atmospheric pressure vary with altitude. Air suitable for use in photosynthesis by terrestrial plants and respiration of terrestrial animals is found within the troposphere.[3]

The study of Earth's atmosphere and its processes is called atmospheric science (aerology), and includes multiple subfields, such as climatology and atmospheric physics. Early pioneers in the field include Léon Teisserenc de Bort and Richard Assmann.[4] The study of the historic atmosphere is called paleoclimatology.

Composition

[edit]

The three major constituents of Earth's atmosphere are nitrogen, oxygen, and argon. Water vapor accounts for roughly 0.25% of the atmosphere by mass. In the lower atmosphere, the concentration of water vapor (a greenhouse gas) varies significantly from around 10 ppm by mole fraction in the coldest portions of the atmosphere to as much as 5% by mole fraction in hot, humid air masses, and concentrations of other atmospheric gases are typically quoted in terms of dry air (without water vapor).[8]: 8 The remaining gases are often referred to as trace gases,[9] among which are other greenhouse gases, principally carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and ozone. Besides argon, other noble gases, neon, helium, krypton, and xenon are also present. Filtered air includes trace amounts of many other chemical compounds.[10]

Many substances of natural origin may be present in locally and seasonally variable small amounts as aerosols in an unfiltered air sample, including dust of mineral and organic composition, pollen and spores, sea spray, and volcanic ash.[11] Various industrial pollutants also may be present as gases or aerosols, such as chlorine (elemental or in compounds),[12] fluorine compounds,[13] and elemental mercury vapor.[14] Sulfur compounds such as hydrogen sulfide and sulfur dioxide (SO2) may be derived from natural sources or from industrial air pollution.[11][15]

| Dry air | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas | Volume fraction(A) | Mass fraction | |||

| Name | Formula | in ppm(B) | in % | in ppm | in % |

| Nitrogen | N2 | 780,800 | 78.08 | 755,200 | 75.52 |

| Oxygen | O2 | 209,500 | 20.95 | 231,400 | 23.14 |

| Argon | Ar | 9,340 | 0.9340 | 12,900 | 1.29 |

| Carbon dioxide[6] | CO2 | 412 | 0.0412 | 626 | 0.063 |

| Neon | Ne | 18.2 | 0.00182 | 12.7 | 0.00127 |

| Helium | He | 5.24 | 0.000524 | 0.724 | 0.0000724 |

| Methane[7] | CH4 | 1.79 | 0.000179 | 0.99 | 0.000099 |

| Krypton | Kr | 1.14 | 0.000114 | 3.3 | 0.00033 |

| If air is not dry: | |||||

| Water vapor(D) | H2O | 0–30,000(D) | 0–3%(E) | ||

|

The total ppm above adds up to more than 1 million (currently 83.43 above it) due to experimental error. | |||||

The average molecular weight of dry air, which can be used to calculate densities or to convert between mole fraction and mass fraction, is about 28.946[17] or 28.964[18][5]: 257 g/mol. This is decreased when the air is humid.

Up to an altitude of around 100 km (62 mi), atmospheric turbulence mixes the component gases so that their relative concentrations remain the same. There exists a transition zone from roughly 80 to 120 km (50 to 75 mi) where this turbulent mixing gradually yields to molecular diffusion. The latter process forms the heterosphere where the relative concentration of lighter gases increase with altitude.[19]

Stratification

[edit]

In general, air pressure and density decrease with altitude in the atmosphere. However, temperature has a more complicated profile with altitude and may remain relatively constant or even increase with altitude in some regions (see the temperature section).[21] Because the general pattern of the temperature/altitude profile, or lapse rate, is constant and measurable by means of instrumented balloon soundings, the temperature behavior provides a useful metric to distinguish atmospheric layers. This atmospheric stratification divides the Earth's atmosphere into five main layers with these typical altitude ranges:[22][23]

- Exosphere: 700–10,000 km (435–6,214 mi)[24]

- Thermosphere: 80–700 km (50–435 mi)[25]

- Mesosphere: 50–80 km (31–50 mi)

- Stratosphere: 12–50 km (7–31 mi)

- Troposphere: 0–12 km (0–7 mi)[26]

Exosphere

[edit]The exosphere is the outermost layer of Earth's atmosphere (though it is so tenuous that some scientists consider it to be part of interplanetary space rather than part of the atmosphere). It extends from the thermopause (also known as the "exobase") at the top of the thermosphere to a poorly defined boundary with the solar wind and interplanetary medium. The altitude of the exobase varies from about 500 kilometres (310 mi; 1,600,000 ft) to about 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) in times of higher incoming solar radiation.[27]

The upper limit varies depending on the definition. Various authorities consider it to end at about 10,000 kilometres (6,200 mi)[28] or about 190,000 kilometres (120,000 mi)—about halfway to the moon, where the influence of Earth's gravity is about the same as radiation pressure from sunlight.[27] The geocorona visible in the far ultraviolet (caused by neutral hydrogen) extends to at least 100,000 kilometres (62,000 mi).[27]

This layer is mainly composed of extremely low densities of hydrogen, with limited amounts of helium, carbon dioxide, and nascent oxygen closer to the exobase.[29] The atoms and molecules are so far apart that they can travel hundreds of kilometres without colliding with one another.[21]: 14–4 Thus, the exosphere no longer behaves like a gas, and the particles constantly escape into space. These free-moving particles follow ballistic trajectories and may migrate in and out of the magnetosphere or the solar wind. Every second, the Earth loses about 3 kg of hydrogen, 50 g of helium, and much smaller amounts of other constituents.[30]

The exosphere is too far above Earth for meteorological phenomena to be possible. The exosphere contains many of the artificial satellites that orbit Earth.[31]

Thermosphere

[edit]The thermosphere is the second-highest layer of Earth's atmosphere. It extends from the mesopause (which separates it from the mesosphere) at an altitude of about 80 km (50 mi) up to the thermopause at an altitude range of 500–1000 km (310–620 mi). The height of the thermopause varies considerably due to changes in solar activity.[25] The passage of the dusk and dawn solar terminator creates background density perturbations up to a factor of two through this layer, forming a dominant feature in this region.[32] Because the thermopause lies at the lower boundary of the exosphere, it is also referred to as the exobase. Overlapping the thermosphere, from 50 to 600 kilometres (31 to 373 mi) above Earth's surface, is the ionosphere – a region of enhanced plasma density.[33][34]

The temperature of the thermosphere gradually increases with height and can rise as high as 1500 °C (2700 °F), though the gas molecules are so far apart that its temperature in the usual sense is not very meaningful. This temperature increase is caused by absorption of ionizing UV and X-ray emission from the Sun.[34][35] The air is so rarefied that an individual molecule (of oxygen, for example) travels an average of 1 kilometre (0.62 mi; 3300 ft) between collisions with other molecules.[36] Although the thermosphere has a high proportion of molecules with high energy, it would not feel hot to a human in direct contact, because its density is too low to conduct a significant amount of energy to or from the skin.[34]

This layer is completely cloudless and free of water vapor. However, non-hydrometeorological phenomena such as the aurora borealis and aurora australis are occasionally seen in the thermosphere at an altitude of around 100 km (62 mi).[37] The colors of the aurora are linked to the properties of the atmosphere at the altitude they occur. The most common is the green aurora, which comes from atomic oxygen in the 1S state, and occurs at altitudes from 120 to 400 km (75 to 250 mi).[38] The International Space Station orbits in the thermosphere, between 370 and 460 km (230 and 290 mi).[39] It is this layer where many of the satellites orbiting the Earth are present.[31]

Mesosphere

[edit]

The mesosphere is the third highest layer of Earth's atmosphere, occupying the region above the stratosphere and below the thermosphere. It extends from the stratopause at an altitude of about 50 km (31 mi) to the mesopause at 80–85 km (50–53 mi) above sea level.[34] Temperatures drop with increasing altitude to the mesopause that marks the top of this middle layer of the atmosphere. It is the coldest place on Earth and has an average temperature around −85 °C (−120 °F; 190 K).[40][41] Because the atmosphere absorbs sound waves at a rate that is proportional to the square of the frequency, audible sounds from the ground do not reach the mesosphere. Infrasonic waves can reach this altitude, but they are difficult to emit at a high power level.[42]

Just below the mesopause, the air is so cold that even the very scarce water vapor at this altitude can condense into polar-mesospheric noctilucent clouds of ice particles. These are the highest clouds in the atmosphere and may be visible to the naked eye if sunlight reflects off them about an hour or two after sunset or similarly before sunrise. They are most readily visible when the Sun is around 4 to 16 degrees below the horizon.[43]

Lightning-induced discharges known as transient luminous events (TLEs) occasionally form in the mesosphere above tropospheric thunderclouds.[44] The mesosphere is also the layer where most meteors and satellites burn up upon atmospheric entrance.[34][45] It is too high above Earth to be accessible to jet-powered aircraft and balloons, and too low to permit orbital spacecraft. The mesosphere is mainly accessed by sounding rockets and rocket-powered aircraft.[46]

Stratosphere

[edit]

The stratosphere is the second-lowest layer of Earth's atmosphere. It lies above the troposphere and is separated from it by the tropopause. This layer extends from the top of the troposphere at roughly 12 km (7.5 mi) above Earth's surface to the stratopause at an altitude of about 50 to 55 km (31 to 34 mi).[22] 99% of the total mass of the atmosphere lies below 30 km (19 mi),[47] and the atmospheric pressure at the top of the stratosphere is roughly 1/1000 the pressure at sea level.[48] It contains the ozone layer, which is the part of Earth's atmosphere that contains relatively high concentrations of that gas.[49]

The stratosphere defines a layer in which temperatures rise with increasing altitude. This rise in temperature is caused by the absorption of ultraviolet radiation (UV) from the Sun by the ozone layer, which restricts turbulence and mixing. Although the temperature may be −80 °C (−110 °F; 190 K) at the tropopause, the top of the stratosphere is much warmer, and may be just below 0 °C.[50][49] This layer is unique to the Earth; neither Mars nor Venus have a stratosphere because of low abundances of oxygen in their atmospheres.[51]

The stratospheric temperature profile creates very stable atmospheric conditions, so the stratosphere lacks the weather-producing air turbulence that is so prevalent in the troposphere. Consequently, the stratosphere is almost completely free of clouds and other forms of weather.[49] However, polar stratospheric or nacreous clouds are occasionally seen in the lower part of this layer of the atmosphere where the air is coldest.[52] The stratosphere is the highest layer that can be accessed by jet-powered aircraft.[53]

Troposphere

[edit]

The troposphere is the lowest layer of Earth's atmosphere. It extends from Earth's surface to an average height of about 12 km (7.5 mi), although this altitude varies from about 9 km (5.6 mi) at the geographic poles to 17 km (11 mi) at the Equator,[26] with some variation due to weather. The troposphere is bounded above by the tropopause, a boundary marked in most places by a temperature inversion (i.e. a layer of relatively warm air above a colder one), and in others by a zone that is isothermal with height.[54][55]

Although variations do occur, the temperature usually declines with increasing altitude in the troposphere because the troposphere is mostly heated through energy transfer from the surface. Thus, the lowest part of the troposphere (i.e. Earth's surface) is typically the warmest section of the troposphere. This promotes vertical mixing (hence, the origin of its name in the Greek word τρόπος, tropos, meaning "turn").[56] The troposphere contains roughly 80% of the mass of Earth's atmosphere.[57] The troposphere is denser than all its overlying layers because a larger atmospheric weight sits on top of the troposphere and causes it to be more severely compressed. Fifty percent of the total mass of the atmosphere is located in the lower 5.5 km (3.4 mi) of the troposphere.[47]

Nearly all atmospheric water vapor or moisture is found in the troposphere, so it is the layer where most of Earth's weather takes place. The ability of the atmosphere to retain water decreases as the temperature declines, so 90% of the water vapor is held in the lower part of the troposphere.[58] It has basically all the weather-associated cloud genus types generated by active wind circulation, although very tall cumulonimbus thunder clouds can penetrate the tropopause from below and rise into the lower part of the stratosphere.[59] Most conventional aviation activity takes place in the troposphere, and it is the only layer accessible by propeller-driven aircraft.[53] Contrails are formed from jet engine water emission at altitudes where the atmospheric temperature is about −53 °C (−63 °F); typically around 7.7 km (4.8 mi) for modern engines.[60]

Other layers

[edit]Within the five principal layers above, which are largely determined by temperature, several secondary layers may be distinguished by other properties:

- The ozone layer is contained within the stratosphere. In this layer ozone reaches a peak concentration of 15 parts per million at an altitude of 32 km (20 mi), which is much higher than in the lower atmosphere but still very small compared to the main components of the atmosphere.[61] It is mainly located in the lower portion of the stratosphere from about 15–35 km (9.3–21.7 mi),[5]: 260 though the thickness varies seasonally and geographically. About 90% of the ozone in Earth's atmosphere is contained in the stratosphere.[62]

- The ionosphere is a region of the atmosphere that is ionized by solar radiation. It plays a significant role in auroras, airglow, and space weather phenomenon.[63][64] During daytime hours, it stretches from 50 to 1,000 km (31 to 621 mi) and includes the mesosphere, thermosphere, and parts of the exosphere. However, ionization in the mesosphere largely ceases during the night.[65] The ionosphere forms the inner edge of the plasmasphere – the inner magnetosphere.[66] It has practical importance because it influences, for example, radio propagation on Earth.[67]

- The homosphere and heterosphere are defined by whether the atmospheric gases are well mixed. The surface-based homosphere includes the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, and the lowest part of the thermosphere, where the chemical composition of the atmosphere does not depend on molecular weight because the gases are mixed by turbulence.[68] This relatively homogeneous layer ends at the turbopause found at about 100 km (62 mi; 330,000 ft),[19] the very edge of space itself as accepted by the FAI, which places it about 20 km (12 mi; 66,000 ft) above the mesopause.

- Above this altitude lies the heterosphere, which includes the exosphere and most of the thermosphere. Here, the chemical composition varies with altitude. This is because the distance that particles can move without colliding with one another is large compared with the size of motions that cause mixing. This allows the gases to stratify by molecular weight,[19] with the heavier ones, such as oxygen and nitrogen, present only near the bottom of the heterosphere. The upper part of the heterosphere is composed almost completely of hydrogen, the lightest element.[69]

- The planetary boundary layer is the part of the troposphere that is closest to Earth's surface and is directly affected by it, mainly through turbulent diffusion. During the day the planetary boundary layer usually is well-mixed, whereas at night it becomes stably stratified with weak or intermittent mixing. The depth of the planetary boundary layer ranges from as little as about 100 metres (330 ft) on clear, calm nights to 1,000–1,500 m (3,300–4,900 ft) or more during the afternoon.[70]

- The barosphere is the region of the atmosphere where the barometric law applies. It ranges from the ground to the thermopause. Above this altitude, the velocity distribution is non-Maxwellian due to high velocity atoms and molecules being able to escape the atmosphere.[71]

The average temperature of the atmosphere at Earth's surface is 14 °C (57 °F; 287 K)[72] or 15 °C (59 °F; 288 K),[73] depending on the reference.[74][75][76]

Physical properties

[edit]

Pressure and thickness

[edit]The average atmospheric pressure at sea level is defined by the International Standard Atmosphere as 101325 pascals (760.00 Torr; 14.6959 psi; 760.00 mmHg).[5]: 257 This is sometimes referred to as a unit of standard atmospheres (atm). Total atmospheric mass is 5.1480×1018 kg (1.13494×1019 lb),[78] about 2.5% less than would be inferred from the average sea-level pressure and Earth's area of 51007.2 megahectares,[5]: 240 this portion being displaced by Earth's mountainous terrain. Atmospheric pressure is the total weight of the air above unit area at the point where the pressure is measured. Thus air pressure varies with location and weather.

Air pressure decreases exponentially with altitude at a rate that depends on the air temperature. The rate of decrease is determined by a temperature-dependent parameter called the scale height: for each increase in altitude by this height, the pressure decreases by a factor of e (the base of natural logarithms, approximately 2.718). For Earth, this value is typically 5.5 to 6 km for altitudes up to around 80 km (50 mi).[79] However, the atmosphere is more accurately modeled with a customized equation for each layer that takes gradients of temperature, molecular composition, solar radiation and gravity into account. At heights over 100 km, the atmosphere is not well mixed, so each chemical species has its own scale height. At altitudes of 200 to 300 km, the combined scale height is 20 to 30 km.[79]

The mass of Earth's atmosphere is distributed approximately as follows:[80]

- 50% is below 5.6 km (18,000 ft)

- 90% is below 16 km (52,000 ft)

- 99.99997% is below 100 km (62 mi; 330,000 ft), the Kármán line. By international convention, this marks the beginning of space where human travelers are considered astronauts.

By comparison, the summit of Mount Everest is at 8,848 m (29,029 ft); commercial airliners typically cruise between 9 and 12 km (30,000 and 38,000 ft),[81] where the lower density and temperature of the air improve fuel economy; weather balloons reach about 35 km (115,000 ft);[82] and the highest X-15 flight in 1963 reached 108.0 km (354,300 ft).

Even above the Kármán line, significant atmospheric effects such as auroras still occur.[37] Meteors begin to glow in this region,[34] though the larger ones may not burn up until they penetrate more deeply. The various layers of Earth's ionosphere, important to HF radio propagation, begin below 100 km and extend beyond 500 km. By comparison, the International Space Station typically orbit at 370–460 km,[39] within the F-layer of the ionosphere,[5]: 271 where they encounter enough atmospheric drag to require reboosts every few months, otherwise orbital decay will occur, resulting in a return to Earth.[39] Depending on solar activity, satellites can experience noticeable atmospheric drag at altitudes as high as 600–800 km.[83]

Temperature

[edit]

Starting at sea level, the temperature decreases with altitude until reaching the stratosphere at around 11 km. Above, the temperature stabilizes over a large vertical distance. Starting above about 20 km, the temperature increases with height, due to heating within the ozone layer caused by the capture of significant ultraviolet radiation from the Sun by the molecular oxygen and ozone gas in this region. A second region of increasing temperature with altitude occurs at very high altitudes, in the aptly-named thermosphere above 90 km.[34]

During the night, the ground radiates more energy than it gains from the atmosphere. As energy is conducted from the nearby atmosphere to the cooler ground, it creates a temperature inversion where the local temperature increases with altitude up to around 1,000 m.[84]

Speed of sound

[edit]Because in an ideal gas of constant composition the speed of sound depends only on temperature and not on pressure or density, the speed of sound in the atmosphere with altitude takes on the form of the complicated temperature profile (see illustration to the right), and does not mirror altitudinal changes in density or pressure.[85] For example, at sea level the speed of sound is 340 m/s. At the average temperature of the stratosphere, –60°C, the speed of sound decreases to 290 m/s.[86]

Density and mass

[edit]

The density of air at sea level is about 1.29 kg/m3 (1.29 g/L, 0.00129 g/cm3).[5]: 257 Density is not measured directly but is calculated from measurements of temperature, pressure and humidity using the equation of state for air (a form of the ideal gas law). Atmospheric density decreases as the altitude increases. This variation can be approximately modeled using the barometric formula.[87] More sophisticated models are used to predict the orbital decay of satellites.[88]

The average mass of the atmosphere is about 5 quadrillion (5×1015) tonnes or 1/1,200,000 the mass of Earth. According to the American National Center for Atmospheric Research, "The total mean mass of the atmosphere is 5.1480×1018 kg with an annual range due to water vapor of 1.2 or 1.5×1015 kg, depending on whether surface pressure or water vapor data are used; somewhat smaller than the previous estimate. The mean mass of water vapor is estimated as 1.27×1016 kg and the dry air mass as 5.1352 ±0.0003×1018 kg."[89]

Optical properties

[edit]

Solar radiation (or sunlight) is the energy Earth receives from the Sun. Earth also emits radiation back into space, but at longer wavelengths that humans cannot see. As energy propagates through the atmosphere, it is impacted by the process of radiative transfer. That is, some of the incoming and emitted radiation is subject to absorption, emission, and scattering by the atmosphere. Another portion of the incident energy is reflected,[90][91] with the two most important atmospheric reflectors being dust and clouds. Depending on the properties of the aerosol, clouds can reflect up to 70% of the incident radiation. Globally, clouds reflect 20% of the incoming energy, contributing two thirds of the planet's total albedo.[92] In May 2017, glints of light, seen as twinkling from an orbiting satellite a million miles away, were found to be reflected light from ice crystals in the troposphere.[93][94]

Scattering

[edit]When light passes through Earth's atmosphere, photons interact with it through scattering. If the light does not interact with the atmosphere, it is called direct radiation and is what you see if you were to look directly at the Sun. Indirect radiation is light that has been scattered in the atmosphere. For example, on an overcast day when you cannot see your shadow, there is no direct radiation reaching you, it has all been scattered. As another example, due to a phenomenon called Rayleigh scattering, shorter (blue) wavelengths scatter more easily than longer (red) wavelengths. This is why the sky looks blue; you are seeing scattered blue light. This is also why sunsets are red. Because the Sun is close to the horizon, the Sun's rays pass through more atmosphere than normal before reaching your eye. Much of the blue light has been scattered out, leaving the red light in a sunset.[95]

Absorption

[edit]

Different molecules absorb different wavelengths of radiation. For example, O2 and O3 absorb almost all radiation with wavelengths shorter than 300 nanometres.[96] Water (H2O) absorbs at many wavelengths above 700 nm.[97] When a molecule absorbs a photon, it increases the energy of the molecule. This heats the atmosphere, but the atmosphere also cools by emitting radiation, as discussed below. In astronomical spectroscopy, the absorption of specific frequencies by the atmosphere is referred to as telluric contamination.[98]

The combined absorption spectra of the gases in the atmosphere leave "windows" of low opacity, allowing the transmission of only certain bands of light. The optical window runs from around 300 nm (ultraviolet-C) up into the range humans can see, the visible spectrum (commonly called light), at roughly 400–700 nm and continues to the infrared to around 1100 nm. There are also infrared and radio windows that transmit some infrared and radio waves at longer wavelengths. For example, the radio window runs from about one centimetre to about eleven-metre waves.[99]

Emission

[edit]Emission is the opposite of absorption, it is when an object emits radiation. Objects tend to emit amounts and wavelengths of radiation depending on their "black body" emission curves, therefore hotter objects tend to emit more radiation, with shorter wavelengths. Colder objects emit less radiation, with longer wavelengths. For example, the Sun is approximately 6,000 K (5,730 °C; 10,340 °F), its radiation peaks near 500 nm, and is visible to the human eye. Earth is approximately 290 K (17 °C; 62 °F), so its radiation peaks near 10,000 nm, and is much too long to be visible to humans.[100]

Because of its temperature, the atmosphere emits infrared radiation. For example, on clear nights Earth's surface cools down faster than on cloudy nights. This is because clouds (H2O) are strong absorbers and emitters of infrared radiation.[101] This is also why it becomes colder at night at higher elevations.

The greenhouse effect is directly related to this absorption and emission effect. Some gases in the atmosphere absorb and emit infrared radiation, but do not interact in this manner with sunlight in the visible spectrum. Common examples of these are CO2 and H2O.[102] Without greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the average temperature of Earth's surface would be a frozen −18 °C (0 °F), rather than the present comfortable average of 15 °C (59 °F).[103]

Refractive index

[edit]

The refractive index of air is close to, but just greater than, 1.[104] Systematic variations in the refractive index can lead to the bending of light rays over long optical paths. One example is that, under some circumstances, observers on board ships can see other vessels just over the horizon because light is refracted in the same direction as the curvature of Earth's surface.[105]

The refractive index of air depends on temperature,[106] giving rise to refraction effects when the temperature gradient is large. An example of such effects is the mirage.[107]

Circulation

[edit]

Atmospheric circulation is the large-scale movement of air through the troposphere, and the means (with ocean circulation) by which heat is distributed around Earth. The large-scale structure of the atmospheric circulation varies from year to year, but the basic structure remains fairly constant because it is determined by Earth's rotation rate and the difference in solar radiation between the equator and poles. The axial tilt of the planet means the location of maximum heat is continually changing, resulting in seasonal variations. The uneven distribution of land and water further breaks up the flow of air.[108]

The flow of air around the planet is divided into three main convection cells by latitude. Around the equator, the Hadley cell is driven by the rising flow of air along the equator. In the upper atmosphere, this air flows toward the poles. At mid latitudes, this circulation is reversed, with ground air flowing toward the poles with the Ferrel cell. Finally, in the high latitudes is the Polar cell, where air again rises and flows toward the poles.[108]

The interface between these cells is responsible for jet streams. These are narrow, fast moving bands that flow from west to east and typically form at an elevation of around 9,100 m (30,000 ft). Jet streams can shift around depending on conditions. They are strongest in winter, when the boundaries between hot and cold air are the most pronounced.[109] In the middle latitudes, it is instabilities in the jet streams that are responsible for moving weather systems.[110]

As with the oceans, the Earth's atmosphere is subject to waves and tidal forces. These are triggered by non-uniform heating by the Sun, and by the daily solar cycle, respectively. Wave-like behavior can occur on a variety of scales, from smaller gravity waves that transfer momentum into the higher atmospheric layers, to much larger planetary waves, or Rossby waves. Atmospheric tides are periodic oscillations of the troposphere and stratosphere that transport energy to the upper atmosphere.[111]

Evolution of Earth's atmosphere

[edit]Earliest atmosphere

[edit]The first atmosphere, during the Early Earth's Hadean eon, consisted of gases in the solar nebula, primarily hydrogen, and probably simple hydrides such as those now found in the gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn), notably water vapor, methane and ammonia. During this earliest era, the Moon-forming collision and numerous impacts with large meteorites heated the atmosphere, driving off the most volatile gases. The collision with Theia, in particular, melted and ejected large portions of Earth's mantle and crust and outgassed significant amounts of steam which eventually cooled and condensed to contribute to ocean water at the end of the Hadean.[112]: 10

Second atmosphere

[edit]The increasing solidification of Earth's crust at the end of the Hadean closed off most of the advective heat transfer to the surface, causing the atmosphere to cool, which condensed most of the water vapor out of the air precipitating into a superocean. Further outgassing from volcanism, supplemented by gases introduced by huge asteroids during the Late Heavy Bombardment, created the subsequent Archean atmosphere, which consisted largely of nitrogen plus carbon dioxide, methane and inert gases.[112] A major part of carbon dioxide emissions dissolved in water and reacted with metals such as calcium and magnesium during weathering of crustal rocks to form carbonates that were deposited as sediments. Water-related sediments have been found that date from as early as 3.8 billion years ago.[113]

About 3.4 billion years ago, nitrogen formed the major component of the then-stable "second atmosphere". The influence of the evolution of life has to be taken into account rather soon in the history of the atmosphere because hints of earliest life forms appeared as early as 3.5 billion years ago.[114] How Earth at that time maintained a climate warm enough for liquid water and life, if the early Sun put out 30% lower solar radiance than today, is a puzzle known as the "faint young Sun paradox".[115]

The geological record however shows a continuous relatively warm surface during the complete early temperature record of Earth – with the exception of one cold glacial phase about 2.4 billion years ago. In the late Neoarchean, an oxygen-containing atmosphere began to develop, apparently due to a billion years of cyanobacterial photosynthesis (known as the Great Oxygenation Event),[116] which have been found as stromatolite fossils from 2.7 billion years ago. The early basic carbon isotopy (isotope ratio proportions) strongly suggests conditions similar to the current, and that the fundamental features of the carbon cycle became established as early as 4 billion years ago.[117]

Ancient sediments in the Gabon dating from between about 2.15 and 2.08 billion years ago provide a record of Earth's dynamic oxygenation evolution. These fluctuations in oxygenation were likely driven by the Lomagundi-Jatuli Carbon Isotope Excursion.[118]

Third atmosphere

[edit]The constant re-arrangement of continents by plate tectonics influences the long-term evolution of the atmosphere by transferring carbon dioxide to and from large continental carbonate stores. Free oxygen did not exist in the atmosphere until about 2.4 billion years ago during the Great Oxygenation Event[119] and its appearance is indicated by the end of banded iron formations (which signals the depletion of substrates that can react with oxygen to produce ferric deposits) during the early Proterozoic eon.[120]

Before this time, any oxygen produced by cyanobacterial photosynthesis would be readily removed by the oxidation of reducing substances on the Earth's surface, notably ferrous iron, sulfur and atmospheric methane. Free oxygen molecules did not start to accumulate in the atmosphere until the rate of production of oxygen began to exceed the availability of reductant materials that removed oxygen. This point signifies a shift from a reducing atmosphere to an oxidizing atmosphere.[121] O2 showed major variations during the Proterozoic, including a billion-year period of euxinia, until reaching a steady state of more than 15% by the end of the Precambrian.[122]

The rise of the more robust eukaryotic photoautotrophs (green and red algae) injected further oxygenation into the air, especially after the end of the Cryogenian global glaciation, which was followed by an evolutionary radiation event during the Ediacaran period known as the Avalon explosion, where complex metazoan life forms (including the earliest cnidarians, placozoans and bilaterians) first proliferated. The following time span from 539 million years ago to the present day is the Phanerozoic eon, during the earliest period of which, the Cambrian, more actively moving metazoan life began to appear and rapidly diversify in another radiation event called the Cambrian explosion, whose locomotive metabolism was fuelled by the rising oxygen level.[123]

The amount of oxygen in the atmosphere has fluctuated over the last 600 million years, reaching a peak of about 35% around 280 million years ago during the Carboniferous period, significantly higher than today's 21%.[126] Two main processes govern changes in the atmosphere: the evolution of plants and their increasing role in carbon fixation, and the consumption of oxygen by rapidly diversifying animal faunae and also by plants for photorespiration and their own metabolic needs at night. Breakdown of pyrite and volcanic eruptions release sulfur into the atmosphere, which reacts and hence reduces oxygen in the atmosphere.[127] However, volcanic eruptions also release carbon dioxide,[128] which can fuel oxygenic photosynthesis by terrestrial and aquatic plants. The cause of the variation of the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere is not precisely understood. Periods with more oxygen in the atmosphere were often associated with more rapid development of animals.[119]

Air pollution

[edit]Air pollution is the introduction of airborne chemicals, particulate matter or biological materials that cause harm or discomfort to organisms.[129] The population growth, industrialization and motorization of human societies have significantly increased the amount of airborne pollutants in the Earth's atmosphere, causing noticeable problems such as smogs, acid rains and pollution-related diseases. The depletion of the stratospheric ozone layer, which shields the surface from harmful ionizing ultraviolet radiations, is also caused by air pollution, chiefly from chlorofluorocarbons and other ozone-depleting substances.[130]

Since 1750, human activity, especially after the Industrial Revolution, has increased the concentrations of various greenhouse gases, most importantly carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide. Greenhouse gas emissions, coupled with deforestation and destruction of wetlands via logging and land developments, have caused an observed rise in global temperatures, with the global average surface temperatures being 1.1 °C higher in the 2011–2020 decade than they were in 1850.[131] It has raised concerns of man-made climate change, which can have significant environmental impacts such as sea level rise, ocean acidification, glacial retreat (which threatens water security), increasing extreme weather events and wildfires, ecological collapse and mass dying of wildlife.[132]

See also

[edit]- Aerial perspective

- Air (classical element)

- Airshed

- Atmospheric dispersion modeling

- Atmospheric electricity

- Biosphere

- Climate system

- COSPAR International Reference Atmosphere (CIRA)

- Environmental impact of aviation

- Global dimming

- Global surface temperature

- Hydrosphere

- Lithosphere

- Reference atmospheric model

References

[edit]- ^ "Gateway to Astronaut Photos of Earth". NASA. Retrieved 2018-01-29.

- ^ Lide, David R., ed. (May 28, 1996). Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (77th ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. pp. 14–17. ISBN 978-0-8493-0477-4.

- ^ "What Is... Earth's Atmosphere? - NASA". 2024-05-13. Retrieved 2024-06-18.

- ^ Vázquez, M.; Hanslmeier, A. (2006). "Historical Introduction". Ultraviolet Radiation in the Solar System. Astrophysics and Space Science Library. Vol. 331. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 17. Bibcode:2005ASSL..331.....V. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3730-9_1. ISBN 978-1-4020-3730-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cox, Arthur N., ed. (2002). "11. Earth". Allen's Astrophysical Quantities (4th ed.). New York, NY: Springer New York. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-1186-0. ISBN 978-1-4612-7037-9.

- ^ a b "Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide", Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network, NOAA, 2019, retrieved 2019-05-31

- ^ a b "Trends in Atmospheric Methane", Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network, NOAA, 2019, retrieved 2019-05-31

- ^ a b Wallace, John M.; Hobbs, Peter V. (2006). "Chapter 1. Introduction and Overview". Atmospheric Science: An Introductory Survey (PDF) (Second ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-0-12-732951-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-28. Retrieved 2018-07-28.

- ^ "Trace Gases". Encyclopedia of the Atmospheric Environment. Archived from the original on 9 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ^ Graedel, T. E.; et al. (2012). Atmospheric Chemical Compounds: Sources, Occurrence and Bioassay. Elsevier. pp. v–ix. ISBN 978-0-08-091842-6.

- ^ a b Colbeck, Ian; Lazaridis, Mihalis (February 2010). "Aerosols and environmental pollution". Naturwissenschaften. 97 (2): 117–131. Bibcode:2010NW.....97..117C. doi:10.1007/s00114-009-0594-x. PMID 19727639.

- ^ Wang, Hao; et al. (2017). "Mixed Chloride Aerosols and their Atmospheric Implications: A Review". Aerosol and Air Quality Research. 17 (4). Taiwan Association for Aerosol Research: 878–887. Bibcode:2017AAQR...17..878W. doi:10.4209/aaqr.2016.09.0383. hdl:10397/103030.

- ^ Faust, J. A. (February 22, 2023). "PFAS on atmospheric aerosol particles: a review". Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts. 25 (2): 133–150. doi:10.1039/d2em00002d. PMID 35416231.

- ^ Pacyna, Jozef M.; et al. (October 2016). "Current and future levels of mercury atmospheric pollution on a global scale". Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 16 (19): 12495–12511. Bibcode:2016ACP....1612495P. doi:10.5194/acp-16-12495-2016. hdl:11250/2452800.

- ^ Kumar, Manoj; Francisco, Joseph S. (January 2017). "Elemental sulfur aerosol-forming mechanism". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (5): 864–869. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114..864K. doi:10.1073/pnas.1620870114. PMC 5293086. PMID 28096368.

- ^ Jacob, Daniel J. (1999). Introduction to atmospheric chemistry (Online-Ausg ed.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4154-7.

- ^ Möller, Detlev (2003). Luft: Chemie, Physik, Biologie, Reinhaltung, Recht. Walter de Gruyter. p. 173. ISBN 3-11-016431-0.

- ^ Çengel, Yunus (2013). Termodinamica e trasmissione del calore (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-88-386-6511-0.

- ^ a b c Schlatter, Thomas W. (2009). "Atmospheric Composition and Vertical Structure". Environmental Impact and Manufacturing. Vol. 6. pp. 1–54. Retrieved 2025-07-20. See p. 6.

- ^ Brekke, Asgeir (2013). Physics of the Upper Polar Atmosphere. Springer Atmospheric Sciences. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-27401-5. ISBN 978-3-642-27400-8.

- ^ a b Champion, K. S. W.; et al. (1985). "Standard and reference atmospheres". In Jursa, Adolf S. (ed.). Handbook of geophysics and the space environment (PDF). Air Force Geophysics Library. Retrieved 2025-07-20.

- ^ a b Buis, Alan (October 22, 2024). "Earth's Atmosphere: A Multi-layered Cake". NASA. Retrieved 2025-07-21.

- ^ Zell, Holly (March 2, 2015). "Earth's Upper Atmosphere". NASA. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

- ^ "Exosphere - overview". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. 2011. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ a b Russell, Randy (2008). "The Thermosphere". National Earth Science Teachers Association (NESTA). Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ a b Geerts, B.; Linacre, E. (November 1997). "The height of the tropopause". Department of Atmospheric Science, University of Wyoming. Archived from the original on February 22, 2001. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ a b c "Exosphere - overview". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. 2011. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- ^ "Earth's Atmospheric Layers". NASA. January 22, 2013.

- ^ Singh, Vir (2020). Environmental Plant Physiology: Botanical Strategies for a Climate Smart Planet. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-000-02486-9.

- ^ Catling, David C.; Zahnle, Kevin J. (May 2009). "The Planetary Air Leak" (PDF). Scientific American. 300 (5): 36–43. Bibcode:2009SciAm.300e..36C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0509-36 (inactive 21 July 2025). PMID 19438047. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ a b Liou, J.-C.; Johnson, N. L. (2008). "Instability of the present LEO satellite populations". Advances in Space Research. 41 (7): 1046–1053. Bibcode:2008AdSpR..41.1046L. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2007.04.081. hdl:2060/20060024585.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, D. J.; et al. (June 16, 2025). "Solar Terminator Waves Revealed as Dominant Features of Upper Thermospheric Density". Geophysical Research Letters. 52 (11) e2025GL115612: 1. Bibcode:2025GeoRL..5215612F. doi:10.1029/2025GL115612.

- ^ Blaunstein, Nathan; Plohotniuc, Eugeniu (May 13, 2008). Ionosphere and Applied Aspects of Radio Communication and Radar. CRC Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4200-5517-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Layers of the Atmosphere". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 20, 2024. Retrieved 2025-07-21.

- ^ Flock, Warren L. (1987). Propagation effects on satellite systems at frequencies below 10 GHz – a handbook for satellite system design. NASA Reference Publication. Vol. 1108 (2nd ed.). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. pp. 1–19 to 1–22.

- ^ Ahrens, C. Donald (2005). Essentials of Meteorology (4th ed.). Thomson Brooks/Cole. ISBN 978-0-534-40679-0.

- ^ a b Lodders, Katharina; Fegley, Jr, Bruce (2015). Chemistry of the Solar System. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-78262-601-5.

- ^ "Aurora Tutorial". Space Weather Prediction Center, NOAA. Retrieved 2025-07-26.

- ^ a b c "International Space Station". NASA. May 23, 2023. Retrieved 2025-07-23.

- ^ States, Robert J.; Gardner, Chester S. (January 2000). "Thermal Structure of the Mesopause Region (80–105 km) at 40°N Latitude. Part I: Seasonal Variations". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 57 (1): 66–77. Bibcode:2000JAtS...57...66S. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(2000)057<0066:TSOTMR>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Buchdahl, Joe. "Atmosphere, Climate & Environment Information Programme". Encyclopedia of the Atmospheric Environment. Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Archived from the original on 2010-07-01. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ^ Yang, Xunren (2016). Atmospheric Acoustics. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-038302-7.

- ^ Gadsden, Michael; Parvianinen, Pekka (2006). "Observing noctilucent clouds". International Association of Geomagnetism & Aeronomy. Retrieved 2025-07-21.

- ^ Sato, M.; et al. (May 2015). "Overview and early results of the Global Lightning and Sprite Measurements mission". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 120 (9): 3822–3851. Bibcode:2015JGRD..120.3822S. doi:10.1002/2014JD022428.

- ^ Karahan, B.; et al. (April 2025). Lemmens, S.; et al. (eds.). Statistical analysis of destructive satellite re-entry uncertainties (PDF). Procedings of the 9th European Conference on Space Debris, Bonn, Germany, 1–4 April 2025. ESA Space Debris Office. Retrieved 2025-07-22.

- ^ Heatwole, Scott E. (September 2024). "Current usage of sounding rockets to study the upper atmosphere". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 121 (40) e2413285121. id. e2413285121. Bibcode:2024PNAS..12113285H. doi:10.1073/pnas.2413285121. PMC 11459162. PMID 39302994.

- ^ a b Holloway, Ann M.; Wayne, Richard P. (2015). Atmospheric Chemistry. Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-78262-593-3.

- ^ Schmunk, Robert B. (April 3, 2025). "Introduction to Clouds". NASA. Retrieved 2025-07-22.

- ^ a b c Saha, Pijushkanti (2012). Modern Climatology. Allied Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 978-81-8424-756-5.

- ^ Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences (1993). "stratopause". Archived from the original on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2013-10-18.

- ^ de Pater, Imke; Lissauer, Jack J. (2015). Planetary Sciences (2 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-1-316-19569-7.

- ^ Salby, Murry L. (1996). Fundamentals of Atmospheric Physics. International Geophysics. Vol. 61. Elsevier. pp. 283–285. ISBN 978-0-08-053215-8.

- ^ a b Filippone, Antonio (2012). Advanced Aircraft Flight Performance. Cambridge Aerospace Series. Vol. 34. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02400-7.

- ^ Barry, R. G.; Chorley, R. J. (1971). Atmosphere, Weather and Climate. London: Menthuen & Co Ltd. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-416-07940-1.

- ^ Tyson, P. D.; Preston-Whyte, R. A. (2000). The Weather and Climate of Southern Africa (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-19-571806-2.

- ^ Frederick, John E. (2008). Principles of Atmospheric Science. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-7637-4089-4.

- ^ "Troposphere". Concise Encyclopedia of Science & Technology. McGraw-Hill. 1984. ISBN 0-07-045482-5.

It contains about four-fifths of the mass of the whole atmosphere.

- ^ Singh, P.; Singh, Vijay P. (2001). Snow and Glacier Hydrology. Springer Netherlands. p. 56. ISBN 0-7923-6767-7.

- ^ Wang, Pao K.; et al. (November 2009). "Further evidences of deep convective vertical transport of water vapor through the tropopause". Atmospheric Research. 94 (3): 400–408. Bibcode:2009AtmRe..94..400W. doi:10.1016/j.atmosres.2009.06.018.

- ^ Tiwary, Abhishek; Williams, Ian (2018). Air Pollution: Measurement, Modelling and Mitigation (Fourth ed.). CRC Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-1-4987-1946-9.

- ^ "NASA Ozone Watch". NASA Goddard Spaceflight Center. Retrieved 2025-07-22.

- ^ "Science: Ozone Basics". Stratospheric Ozone. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. Retrieved 2025-07-22.

- ^ Newell, Patrick T.; et al. (May 2001). "The role of the ionosphere in aurora and space weather". Reviews of Geophysics. 39 (2): 137–149. Bibcode:2001RvGeo..39..137N. doi:10.1029/1999RG000077.

- ^ Basavaiah, Nathani (2012). Geomagnetism: Solid Earth and Upper Atmosphere Perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-007-0403-9.

- ^ "The Ionosphere". University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 2025-07-23.

- ^ Gallagher, D. L. (April 26, 2023). "The Earth's Plasmasphere". NASA. Retrieved 2025-07-23.

- ^ Kirby, S. S.; et al. (2006). "Studies of the ionosphere and their application to radio transmission" (PDF). Proceedings of the Institute of Radio Engineers. 22 (4): 481–521. doi:10.1109/JRPROC.1934.225867. Retrieved 2025-07-23.

- ^ "homosphere – AMS Glossary". Amsglossary.allenpress.com. Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ^ Helmenstine, Anne Marie (June 16, 2018). "The 4 Most Abundant Gases in Earth's Atmosphere". Retrieved 2025-07-21.

- ^ Haby, Jeff. "The Planetary Boundary Layer". National Weather Service. Retrieved 2025-07-23.

- ^ Bauer, Siegfried; Lammer, Helmut (2013). Planetary Aeronomy: Atmosphere Environments in Planetary Systems. Physics of Earth and Space Environments. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-3-662-09362-7.

- ^ "Earth's Atmosphere". Archived from the original on 2009-06-14.

- ^ "NASA – Earth Fact Sheet". Nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ^ "Global Surface Temperature Anomalies". Archived from the original on 2009-03-03.

- ^ "Earth's Radiation Balance and Oceanic Heat Fluxes". Archived from the original on 2005-03-03.

- ^ "Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Control Run" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-28.

- ^ Geometric altitude vs. temperature, pressure, density, and the speed of sound derived from the 1962 U.S. Standard Atmosphere.

- ^ Trenberth, Kevin E.; Smith, Lesley (January 1970). "The Mass of the Atmosphere: A Constraint on Global Analyses". Journal of Climate. 18 (6): 864. Bibcode:2005JCli...18..864T. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.727.6573. doi:10.1175/JCLI-3299.1. S2CID 16754900.

- ^ a b Daniel, R. R. (2002). Concepts in Space Science. Universities Press. pp. 70–72. ISBN 978-81-7371-410-8.

- ^ Lutgens, Frederick K.; Tarbuck, Edward J. (1995). The Atmosphere (6th ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 14–17. ISBN 0-13-350612-6.

- ^ Sforza, Pasquale (2014). "Fuselage Design". Commercial Airplane Design Principles. pp. 47–79. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-419953-8.00003-6. ISBN 978-0-12-419953-8.

- ^ Kräuchi, A.; et al. (2016). "Controlled weather balloon ascents and descents for atmospheric research and climate monitoring". Atmospheric Measurement Techniques. 9 (3): 929–938. Bibcode:2016AMT.....9..929K. doi:10.5194/amt-9-929-2016. PMC 5734649. PMID 29263765.

- ^ Anderson, Brian J.; Mitchell, Donald G. (2005). "The Space Environment". In Pisacane, Vincent L. (ed.). Fundamentals of Space Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-19-516205-9.

- ^ "Atmospheric controllers of local nighttime temperature". Pennsylvania State University. 2004. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ Benson, Tom. "Speed of sound". NASA Glenn Research Center. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ Wang, Hongwei (2023). A Guide to Fluid Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-49883-8.

- ^ Hall, Nancy, ed. (May 13, 2021). "Earth Atmosphere Model". NASA Glenn Research Center. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ Kumar, R.; et al. (March 2022). "Simulation of the orbital decay of a spacecraft in low Earth orbit due to aerodynamic drag". The Aeronautical Journal. 126 (1297): 565–583. doi:10.1017/aer.2021.83.

- ^ Trenberth, Kevin E.; Smith, Lesley (March 15, 2005). "The Mass of the Atmosphere: A Constraint on Global Analyses". Journal of Climate. 18 (6): 864–875. Bibcode:2005JCli...18..864T. doi:10.1175/JCLI-3299.1. JSTOR 26253433.

- ^ "Absorption / reflection of sunlight". Understanding Global Change. Retrieved 2023-06-13.

- ^ "The Atmospheric Window". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2023-06-13.

- ^ Sirvatka, Paul. "Radiation and the Earth-atmosphere system: 'Why is the sky blue?'". Introduction to meteorology. College of DuPage. Retrieved 2025-07-25.

- ^ St. Fleur, Nicholas (May 19, 2017). "Spotting Mysterious Twinkles on Earth From a Million Miles Away". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ^ Marshak, Alexander; et al. (May 15, 2017). "Terrestrial glint seen from deep space: oriented ice crystals detected from the Lagrangian point". Geophysical Research Letters. 44 (10): 5197. Bibcode:2017GeoRL..44.5197M. doi:10.1002/2017GL073248. hdl:11603/13118. S2CID 109930589.

- ^ Bloomfield, Louis A. (2007). How Everything Works: Making Physics Out of the Ordinary. John Wiley & Sons. p. 456. ISBN 978-0-470-17066-3.

- ^ Ondoh, Tadanori; Marubashi, Katsuhide, eds. (2001). Science of Space Environment. Wave summit course. IOS Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-4-274-90384-7.

- ^ Collins, William D.; et al. (September 2006). "Effects of increased near-infrared absorption by water vapor on the climate system". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 111 (D18). ID D18109. Bibcode:2006JGRD..11118109C. doi:10.1029/2005JD006796.

- ^ Wang, Sharon Xuesong; et al. (November 2022). "Characterizing and Mitigating the Impact of Telluric Absorption in Precise Radial Velocities". The Astronomical Journal. 164 (5). id. 211. arXiv:2206.07287. Bibcode:2022AJ....164..211W. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/ac947a.

- ^ McLean, Ian S. (2008). Electronic Imaging in Astronomy: Detectors and Instrumentation. Astronomy and Planetary Sciences (2nd ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-3-540-76582-0.

- ^ Shelton, Marlyn L. (2009). Hydroclimatology: Perspectives and Applications. Cambridge University Press. pp. 35–37. ISBN 978-0-521-84888-6.

- ^ Bohren, Craig F.; Clothiaux, Eugene E. (2006). Fundamentals of Atmospheric Radiation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 26–29. ISBN 978-3-527-60837-9.

- ^ Wrigglesworth, John (1997). Energy And Life. Lifelines Series. CRC Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-4822-7275-8.

- ^ Ma, Qiancheng (March 1998). "Greenhouse Gases: Refining the Role of Carbon Dioxide". NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ Voronin, A.; Zheltikov, A. (2017). "The generalized Sellmeier equation for air". Scientific Reports. 7 46111. Bibcode:2017NatSR...746111V. doi:10.1038/srep46111. PMC 5569311. PMID 28836624. 46111. Figure 1 gives a refractive index of 1.000273 at 23 C.

- ^ Basey, David (March 2, 2019). "Atmospheric Refraction". British Astronomical Association. Retrieved 2025-07-24.

- ^ Edlén, Bengt (1966). "The refractive index of air". Metrologia. 2 (2): 71–80. Bibcode:1966Metro...2...71E. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/2/2/002.

- ^ Young, Andrew T. (2025). "An Introduction to Mirages". San Diego State University. Retrieved 2025-07-25.

- ^ a b "Global Atmospheric Circulations". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. October 3, 2023. Retrieved 2025-07-25.

- ^ "The Jet Stream". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. December 9, 2024. Retrieved 2025-07-25.

- ^ Shuckburgh, Emily (2011). "Weather and Climate". In Moffatt, H. Keith; Shuckburgh, Emily (eds.). Environmental Hazards: The Fluid Dynamics And Geophysics Of Extreme Events. Lecture Notes Series, Institute For Mathematical Sciences, National University Of Singapore. Vol. 21. World Scientific. p. 87. ISBN 978-981-4464-67-3.

- ^ Volland, Hans (2012). Atmospheric Tidal and Planetary Waves. Atmospheric and Oceanographic Sciences Library. Vol. 12. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-94-009-2861-9.

- ^ a b Zahnle, K.; et al. (2010). "Earth's Earliest Atmospheres". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2 (10) a004895. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a004895. PMC 2944365. PMID 20573713.

- ^ Windley, B. (1984). The Evolving Continents. New York: Wiley Press.

- ^ Schopf, J. (1983). Earth's Earliest Biosphere: Its Origin and Evolution. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Feulner, Georg (2012). "The faint young Sun problem". Reviews of Geophysics. 50 (2) 2011RG000375: RG2006. arXiv:1204.4449. Bibcode:2012RvGeo..50.2006F. doi:10.1029/2011RG000375. S2CID 119248267.

- ^ Lyons, Timothy W.; et al. (February 2014). "The rise of oxygen in Earth's early ocean and atmosphere". Nature. 506 (7488): 307–315. Bibcode:2014Natur.506..307L. doi:10.1038/nature13068. PMID 24553238. S2CID 4443958.

- ^ Hayes, John M.; Waldbauer, Jacob R. (June 29, 2006). "The Carbon Cycle and Associated Redox Processes through Time". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 361 (1470): 931–950. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1840. JSTOR 20209694. PMC 1578725. PMID 16754608.

- ^ Lyons, Timothy W.; et al. (2014). "Atmospheric oxygenation three billion years ago". Nature. 506 (7488): 307–15. Bibcode:2014Natur.506..307L. doi:10.1038/nature13068. PMID 24553238. S2CID 4443958.

- ^ a b Cordeiro, Ingrid Rosenburg; Tanaka, Mikiko (September 2020). "Environmental Oxygen is a Key Modulator of Development and Evolution: From Molecules to Ecology". BioEssays. 42 (9). 2000025. doi:10.1002/bies.202000025. PMID 32656788.

- ^ Lantink, Margriet L.; et al. (February 2018). "Fe isotopes of a 2.4 Ga hematite-rich IF constrain marine redox conditions around the GOE". Precambrian Research. 305: 218–235. Bibcode:2018PreR..305..218L. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2017.12.025. hdl:1874/362652.

- ^ Laakso, T. A.; Schrag, D. P. (May 2017). "A theory of atmospheric oxygen". Geobiology. 15 (3): 366–384. Bibcode:2017Gbio...15..366L. doi:10.1111/gbi.12230. PMID 28378894.

- ^ Scotese, Christopher R. (2010). "Back to Earth History: Summary Chart for the Precambrian". Paleomar Project. Retrieved 2025-07-21.

- ^ Towe, K. M. (April 1970). "Oxygen-Collagen Priority and the Early Metazoan Fossil Record". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 65 (4): 781–788. Bibcode:1970PNAS...65..781T. doi:10.1073/pnas.65.4.781. PMC 282983. PMID 5266150.

- ^ Martin, Daniel; et al. (2016). "The human physiological impact of global deoxygenation". The Journal of Physiological Sciences. 67 (1): 97–106. doi:10.1007/s12576-016-0501-0. ISSN 1880-6546. PMC 5138252. PMID 27848144.

- ^ Riding, R. (October 2009). "An atmospheric stimulus for cyanobacterial-bioinduced calcification ca. 350 million years ago?". PALAIOS. 24 (10): 685–696. Bibcode:2009Palai..24..685R. doi:10.2110/palo.2009.p09-033r. ISSN 0883-1351.

- ^ a b Berner, R. A. (March 2001). "Modeling atmospheric O2 over Phanerozoic time". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 65 (5): 685–694. doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(00)00572-X. ISSN 0016-7037.

- ^ Calvo-Flores, Francisco G. (2025). Understanding the Chemistry of the Environment. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-119-56863-6.

- ^ Gerlach, Terry (June 2011). "Volcanic versus anthropogenic carbon dioxide". Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union. 92 (24): 201–202. Bibcode:2011EOSTr..92..201G. doi:10.1029/2011EO240001.

- ^ "Pollution". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 2025-07-25.

- ^ Harrop, Owen (2003). Air Quality Assessment and Management: A Practical Guide. Clay's Library of Health and the Environment. CRC Press. pp. 30–49. ISBN 978-0-203-30263-7.

- ^ IPCC (2021). "Summary for Policymakers" (PDF). IPCC AR6 WG1. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-08-11. Retrieved 2021-11-20.

- ^ Managing Climate Risks, Facing up to Losses and Damages. Paris: OECD Publishing. November 2021. Bibcode:2021mcrf.book.....O. doi:10.1787/55ea1cc9-en. ISBN 978-92-64-43966-5.

External links

[edit]- Buchan, Alexander (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. III (9th ed.). pp. 28–36.

- Interactive global map of current atmospheric and ocean surface conditions.

Atmosphere of Earth

View on GrokipediaChemical Composition

Major Gases

The dry atmosphere of Earth consists predominantly of nitrogen (N₂), which constitutes 78.08% by volume, oxygen (O₂) at 20.95%, and argon (Ar) at 0.934%.[2] These three gases account for approximately 99.964% of the total dry air composition.[2] Nitrogen (N₂), a diatomic molecule that is colorless and odorless at standard temperature and pressure (STP: 0°C, 1 atm), has a melting point of -210°C, boiling point of -196°C, density of 1.25 g/L, and low water solubility (~0.02 g/L at 20°C). It is highly inert due to the strong N≡N triple bond, does not support combustion, is essential for life but requires fixation for biological use, and plays a key role in diluting reactive gases. Oxygen (O₂), a diatomic molecule that is colorless, odorless, and paramagnetic, has a melting point of -219°C, boiling point of -183°C, density of 1.43 g/L, and slight water solubility (~0.03 g/L at 20°C). It is a strong oxidizing agent that supports combustion and respiration essential for aerobic life. Argon (Ar), a monatomic noble gas that is colorless and odorless, has a melting point of -189°C, boiling point of -186°C, density of 1.78 g/L, and very low water solubility. Chemically inert with no stable compounds under normal conditions, it originates primarily from the radioactive decay of potassium-40 in the Earth's crust.[1] Carbon dioxide (CO₂), a linear triatomic molecule that is colorless and odorless at STP, sublimes at -78.5°C (no liquid phase at 1 atm), has a density of 1.98 g/L, and moderate water solubility (~1.45 g/L at 25°C). Chemically, it is non-flammable, forms carbonic acid in water (a weak acid), is involved in photosynthesis, respiration, and the greenhouse effect, and reacts with bases and some metals. Though present in trace amounts at about 430 parts per million (0.043%) as of June 2025, it is considered among the major variable components due to its influence on climate and its increasing concentration from anthropogenic emissions.[8] This level represents a rise from pre-industrial values of around 280 ppm, driven by fossil fuel combustion and land-use changes.[9] Water vapor, varying from near 0% to 4% depending on temperature and location, is excluded from dry air measurements but is the most abundant greenhouse gas by impact.[1]| Gas | Chemical Formula | Volume Percentage (Dry Air) |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen | N₂ | 78.08 |

| Oxygen | O₂ | 20.95 |

| Argon | Ar | 0.934 |

| Carbon Dioxide | CO₂ | 0.043 (430 ppm, 2025) |

Trace Gases and Variable Components

Trace gases in Earth's atmosphere, defined as those with volume mixing ratios below approximately 1% excluding nitrogen, oxygen, and argon, include carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), nitrous oxide (N₂O), and ozone (O₃), along with minor noble gases such as neon and helium. These gases collectively account for less than 0.1% of dry air by volume, yet play critical roles in radiative forcing, chemical reactions, and atmospheric dynamics.[11] [12] Carbon dioxide, the most abundant anthropogenic trace gas, reached a global average concentration of 425.43 parts per million (ppm) in October 2025, as measured at observatories including Mauna Loa. This represents an increase of about 3.5 ppm from 2024 levels, driven primarily by fossil fuel combustion, deforestation, and cement production, with natural sinks absorbing roughly half of emissions.[13] [14] Methane concentrations average approximately 1,950 parts per billion (ppb), sourced from biogenic processes like wetlands and enteric fermentation, as well as fossil fuel extraction; annual increases have averaged 10-13 ppb in recent years. Nitrous oxide stands at around 336 ppb, mainly from agricultural fertilizers and industrial activities.[15] [16] Ozone concentrations vary greatly by altitude and location, with tropospheric levels typically 20-100 ppb and stratospheric peaks exceeding 10 ppm, formed via photochemical reactions involving oxygen and nitrogen oxides. Other trace constituents, such as neon (18.18 ppm), helium (5.24 ppm), and krypton (1.14 ppm), originate from primordial atmospheric retention and radioactive decay, remaining stable over human timescales.[17] Variable components, primarily water vapor, fluctuate widely and are excluded from standard dry air compositions. Water vapor content ranges from near 0% in arid, cold conditions to 4% by volume in saturated tropical air near the surface, exerting dominant control over local humidity and contributing substantially to the natural greenhouse effect through its high concentration and heat capacity. Aerosols—solid or liquid particles like sulfates, sea salt, and mineral dust—vary temporally with emissions, weather, and seasonal cycles, typically numbering 10-1,000 per cubic centimeter and modulating radiation balance by scattering sunlight and serving as cloud condensation nuclei.[18] [19] [20]| Trace Gas | Approximate Concentration (dry air, ppmv unless noted) | Primary Sources |

|---|---|---|

| CO₂ | 425 | Fossil fuels, respiration, oxidation |

| CH₄ | 1.95 (ppb) | Wetlands, agriculture, leaks |

| N₂O | 0.336 (ppb) | Soils, fertilizers |

| O₃ | 0.3-0.7 (total column average) | Photochemical production |

| Ne | 18.18 | Primordial |

| He | 5.24 | Radioactive decay, solar wind |

Spatial and Temporal Variations

The mixing ratios of the major atmospheric constituents—nitrogen, oxygen, and argon—remain nearly constant with altitude up to the turbopause at approximately 100 km, where diffusive separation begins to dominate over turbulent mixing, leading to gradual fractionation by molecular weight in the heterosphere above.[21] In the lower atmosphere (troposphere and stratosphere), these gases exhibit minimal horizontal spatial variations, typically less than 0.1% deviation from global means, due to their long atmospheric lifetimes exceeding years and efficient global mixing by winds.[5] Temporal fluctuations in their concentrations are similarly negligible on diurnal, seasonal, or even decadal scales, except for anthropogenic influences on oxygen via fossil fuel combustion, which cause a measurable but small decline of about 4 per meg per year globally.[22] Trace gases display more pronounced spatial and temporal variations driven by their sources, sinks, and shorter lifetimes. Carbon dioxide (CO₂), with a global mean mixing ratio of around 420 ppm as of 2023, shows well-mixed background levels but exhibits a seasonal cycle amplitude that increases with latitude in the Northern Hemisphere, ranging from 2-5 ppm near the equator to over 15 ppm at 60°N, primarily due to terrestrial photosynthesis and respiration imbalances over extensive boreal forests and croplands.[23] [24] This cycle peaks in May (Northern Hemisphere winter) and troughs in September, with interhemispheric asymmetry arising from greater landmass and vegetation in the north compared to the ocean-dominated south.[25] Local spatial enhancements occur near emission hotspots like urban areas or biomass burning regions, though atmospheric transport homogenizes these on scales beyond 1000 km within weeks.[26] Water vapor, the most variable constituent, constitutes 0-4% by volume in the troposphere, with spatial maxima in the warm tropics (up to 3-4% near the surface) decreasing poleward to under 0.2% in polar regions due to the Clausius-Clapeyron relation linking saturation vapor pressure to temperature.[27] Temporally, it fluctuates diurnally by 10-20% over land due to evapotranspiration and condensation cycles, and seasonally by up to 50% in monsoon-influenced areas, reflecting precipitation-evaporation dynamics and storm tracks.[28] Unlike longer-lived gases, its short residence time of days to weeks confines variations to regional scales, with negligible presence above the tropopause.[5] Ozone (O₃), a key trace gas, varies sharply with altitude, peaking at 10 ppm in the stratospheric ozone layer around 25-30 km before dropping to tropospheric levels of 20-100 ppb, influenced by photochemical production and transport.[29] In the troposphere, spatial patterns show higher concentrations in the Northern Hemisphere (annual mean ~40 ppb) versus the south (~25 ppb), driven by industrial NOx emissions and continental pollution export.[30] Temporal cycles include summer maxima from enhanced photochemistry and biomass fire seasons, with diurnal peaks in the afternoon; trends indicate increases of 0.5-1 ppb per decade in polluted regions since 1990, though satellite data reveal heterogeneous global patterns.[31] [32] Methane (CH₄) and nitrous oxide (N₂O), well-mixed greenhouse gases, show subdued variations: CH₄ at ~1900 ppb has minor seasonal amplitudes (<10 ppb) from wetland emissions peaking in summer hemispheres, with spatial gradients near sources like rice paddies or oil fields dissipating within months.[5] N₂O at 330 ppb varies even less, with lifetime-driven uniformity except for stratospheric depletion.[33] These patterns underscore how atmospheric lifetime governs variability scale, with short-lived species like reactive hydrocarbons (e.g., isoprene) confined to biogenic hotspots and diurnal cycles.[34]Vertical Stratification

Troposphere

The troposphere constitutes the lowest layer of Earth's atmosphere, bounded above by the tropopause and extending from the surface upward. It encompasses the region where nearly all weather phenomena occur due to intense vertical mixing driven by solar heating of the ground and subsequent convection. This layer holds about 75% of the total mass of the atmosphere and virtually all water vapor, enabling processes like cloud formation and precipitation.[35][36] The thickness of the troposphere varies geographically and seasonally, averaging around 12 kilometers but ranging from approximately 7 kilometers over the poles during winter to 18-20 kilometers near the equator. This variation arises from differences in surface temperature and convection strength, with warmer equatorial air expanding the layer and colder polar air contracting it. The tropopause, marking the upper boundary, is defined as the level where the temperature lapse rate drops below 2 K per kilometer, transitioning to the more stable stratosphere.[37][38][39] Within the troposphere, temperature decreases with altitude at an average environmental lapse rate of about 6.5 °C per kilometer, though this can vary locally due to moisture content and stability. Dry adiabatic lapse rates reach 9.8 °C per kilometer in unsaturated air, while moist processes reduce it to around 5-6 °C per kilometer, influencing thunderstorm development and atmospheric stability. Near the surface, air pressure is highest, decreasing exponentially with height, and the layer supports aviation up to the cruising altitudes of commercial jets, typically below 12 kilometers.[40] The composition mirrors the overall atmosphere—roughly 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, and 1% argon and other inert gases—but includes higher concentrations of variable components like water vapor (up to 4% in humid tropics), aerosols, and pollutants near the surface. Convection currents mix these constituents thoroughly, distributing heat, moisture, and trace gases, which play critical roles in the hydrological cycle and short-term climate regulation.[35][41]Stratosphere

The stratosphere is the atmospheric layer extending from the tropopause, typically at altitudes of approximately 12 to 20 kilometers above Earth's surface, up to about 50 kilometers.[36] Its lower boundary varies latitudinally, reaching as low as 7-10 kilometers near the poles and as high as 17-20 kilometers near the equator.[42] The upper boundary, known as the stratopause, marks a transition to the mesosphere at around 50 kilometers.[43] Unlike the troposphere below, the stratosphere exhibits a temperature inversion, with temperatures increasing with altitude from about -60°C at the base to near 0°C at the top.[44] This warming results from the absorption of ultraviolet radiation by ozone molecules concentrated in the ozone layer, which spans roughly 15 to 35 kilometers altitude.[45] The ozone layer, comprising a peak concentration of about 10 parts per million by volume, effectively shields Earth's surface from harmful solar UV radiation shorter than 290 nanometers.[46] Compositionally, the stratosphere resembles the troposphere in major gases—nitrogen (78%) and oxygen (21%)—but features significantly lower water vapor content, rendering it extremely dry and inhibiting cloud formation except for polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs) in cold polar regions during winter.[44] Ozone constitutes a trace but critical component, accounting for the layer's radiative heating. The region holds about 20% of the atmosphere's total mass despite its thin vertical extent.[47] Vertical stability arises from the density gradient and temperature profile, minimizing turbulence and convection, which confines most weather phenomena to the troposphere.[44] Dynamically, the stratosphere hosts strong zonal winds, including stratospheric jet streams and the polar vortex—a cyclonic circulation of westerly winds encircling the poles at 15-50 kilometers altitude, peaking in winter with speeds exceeding 100 meters per second.[48] The polar vortex influences tropospheric weather patterns by modulating the position of the polar jet stream, with disruptions such as sudden stratospheric warmings potentially leading to cold outbreaks at the surface.[49] Aircraft routinely operate in the lower stratosphere for efficient high-altitude flight, benefiting from reduced drag and stable conditions.[4]Mesosphere

The mesosphere constitutes the atmospheric layer extending from approximately 50 km to 85 km altitude above Earth's surface, positioned between the stratopause and mesopause boundaries.[4] This region features a temperature lapse rate where thermal profiles decline with increasing elevation, culminating in the coldest temperatures of the atmosphere near the mesopause at around -90°C (183 K) or lower during summer conditions.[50] [51] Atmospheric density in the mesosphere diminishes rapidly, with pressures ranging from about 1 mbar at its base to 0.001 mbar at the upper limit, rendering it sparsely populated by molecular nitrogen (N₂) and oxygen (O₂) that comprise over 99% of the gaseous mix, alongside trace water vapor insufficient for significant cloud formation except under specialized conditions.[4] The layer's low density and residual frictional interactions cause most incoming meteoroids to ablate and vaporize upon entry, producing visible meteors primarily within this altitude band due to the balance of sufficient particle collisions for heating without overwhelming ionization seen higher up.[51] Dynamic features include strong zonal winds exceeding 100 m/s in the summer hemisphere and turbulent mixing, contributing to the formation of noctilucent clouds—thin, icy formations at 80-85 km altitude visible at high latitudes during summer twilight, nucleated on meteor-derived dust particles when temperatures drop below -120°C.[36] [52] These polar mesospheric clouds serve as indicators of upper atmospheric cooling trends, with observations linking their increased frequency and southward extension to stratospheric temperature declines.[36] Exploration of the mesosphere remains challenging, as conventional balloons and aircraft cannot access it, relying instead on sounding rockets and remote sensing via lidar or satellite instruments to measure parameters like wind velocities and trace gas distributions, which reveal seasonal variations in composition driven by photodissociation and vertical transport.[51] The upper mesosphere hosts the D-layer of the ionosphere during daylight, where solar radiation ionizes nitric oxide, influencing radio wave propagation but dissipating rapidly at night.[4]Thermosphere