Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Maravar

View on Wikipedia

Maravar (also known as Maravan and Marava) are a Tamil community in the state of Tamil Nadu. These people are one of the three branches of the Mukkulathor confederacy.[1] Members of the Maravar community often use the honorific title Thevar.[2][3][4] They are classified as an Other Backward Class or a Denotified Tribe in Tamil Nadu, depending on the district.[5]

Key Information

The Sethupathi rulers of the erstwhile Ramnad kingdom were from this community.[6] The Maravar community, along with the Kallars, had a reputation for thieving and robbery from as early as the medieval period.[7][8][9][10][11]

Etymology

[edit]The term Maravar has diverse proposed etymologies;[12] it may come simply from a Tamil word maram, meaning such things as vice and murder.[13] or a term meaning "bravery".[14]

Social status

[edit]The Maravars were considered as Shudras and were free to worship in Hindu temples.[15] According to Pamela G, Price, the Maravar were warriors who were in some cases zamindars. The zamins of Singampatti, Urkadu, Nerkattanseval, Thalavankottai, all ruled by members of Maravar caste.[16] Occasionally the Setupathis had to respond to the charge they were not ritually pure.[17]

During the formation of Tamilaham, the Maravars were brought in as socially outcast tribes or traditionally as lowest entrants into the shudra category.[18][citation needed] The Maravas to this day are feared as a thieving tribe and are an ostracised group in Tirunelveli region.[18][19]

Notable people

[edit]- Pasumpon Muthuramalinga Thevar, freedom fighter[20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Dirks, Nicholas B. (1993). The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom. University of Michigan Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-47208-187-5.

- ^ Neill, Stephen (2004). A History of Christianity in India: The Beginnings to AD 1707. Cambridge University Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-52154-885-4.

- ^ Hardgrave, Robert L. (1969). The Nadars of Tamilnad: The Political Culture of a Community in Change. University of California Press. p. 280.

- ^ Pandian, Anand (2009). Crooked Stalks: Cultivating Virtue in South India. Duke University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-82239-101-2.

- ^ "List of Backward Classes Approved".

- ^ Pamela G. Price (14 March 1996). Kingship and Political Practice in Colonial India. Cambridge University Press, 14-Mar-1996 - History - 220 pages. p. 26. ISBN 9780521552479.

- ^ Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2007). Women and Work in Precolonial India: A Reader. Sage Publications. p. 74. ISBN 9789351507406.

- ^ Dirks, Nicholas (2007). The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom. University of Michigan Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780472081875.

- ^ Balasubramanian, R (2001). Social and Economic Dimensions of Caste Organisations in South Indian States. University of Madras. p. 88.

- ^ Oscar Salemink, Peter Pels (2002). Colonial Subjects. Wiesbaden. p. 160. ISBN 0472087460.

- ^ Ferro-Luzzi, Gabriella Eichinger (2002). The Maze of fantasy in Tamil folktales. Wiesbaden. p. Glossary. ISBN 9783447045681.

- ^ VenkatasubramanianIndia, T. K. (1986). Political Change and Agrarian Tradition in South India, C. 1600-1801: A Case Study. Mittal Publications. p. 49.

- ^ Bayly, Susan (2004). Saints, Goddesses and Kings Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700-1900. Taylor and Francis. p. 213. ISBN 9780521372015.

- ^ Ramaswamy, Vijaya (2007). Historical dictionary of the Tamils. Scarecrow Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-8108-5379-9.

- ^ Singer, Milton B.; Cohn, Bernard S. (1970). Structure and Change in Indian Society. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-202-36933-4.

- ^ Stuart, Andrew John (1879). A Manual of the Tinnevelly District in the Presidency of Madras. E. Keys, at the Government Press. p. 24.

- ^ Price, Pamela (1996). Kingship and Political Practice in Colonial India. University of Cambridge. p. 62. ISBN 9780521552479.

- ^ a b Ramasamy, Vijaya (2016). Women and work in Precolonial India. SAGE. p. 62. ISBN 9789351507406.

- ^ Parkin, Robert (2001). Perilous Transactions. Sikshasandhan. p. 130. ISBN 9788187982005.

- ^ Eugene F. Irschick (1986). Tamil Revivalism in the 1930s. Cre-A. p. 239.

Maravar

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Etymology

Etymology

The term Maravar (Tamil: மறவர்) derives from classical Tamil usage denoting inhabitants of arid or hilly tracts, as defined in the Dravidian Etymological Dictionary, which associates maravan with dwellers of desert or Palai (dry forest) landscapes central to the group's historical identity.[5] This philological root aligns with references in post-Sangam texts like the Maturaikkāṇṭam section of Cilappatikāram, where Maravar are portrayed as hunters (veṭṭuvar) tied to the Pālai ecozone, emphasizing a lifestyle of martial self-reliance in marginal terrains.[6] Alternative derivations propose links to Tamil maram, connoting bravery, warrior ethos, or martial ruthlessness interpreted as vice or destruction, reflecting the term's evolution from a descriptive epithet for fierce guardians or combatants in early literature to a fixed caste identifier in medieval inscriptions and colonial ethnographies.[7] In classical grammar, maṟavar exemplifies plural forms for "warriors," underscoring its semantic shift toward denoting organized martial communities without implying unrelated mythical origins.[8]Historical and Mythical Origins

The Maravars appear in the earliest Tamil textual records as a martial community during the Sangam period, roughly spanning 300 BCE to 300 CE, where they are depicted as valiant warriors and hunters inhabiting the arid palai (desert) landscapes of southern Tamilakam. Sangam poems, such as those in the Maturaikkanci, associate them with the vettuvar (hunter) groups, emphasizing their role in clan-based societies skilled in warfare and nomadic pursuits rather than settled agriculture.[6][9] These references provide the oldest empirical attestation of Maravars as a distinct social group in the region, predating later inscriptions or ethnographies, though archaeological evidence specific to their ethnogenesis remains limited to general Iron Age settlement patterns in southern India. Claims of Maravar descent from or close kinship with the ancient Pandya dynasty emerge in oral traditions and colonial-era ethnographies, positing that early Pandyas belonged to the Maravar tribe or integrated them as elite warriors, evidenced by royal epithets like Maravarman adopted by Pandya rulers from at least the 13th century CE onward, such as Maravarman Sundara Pandya I (r. 1216–1238 CE).[10][11] However, epigraphic records, including Pandya inscriptions from sites like Tenkasi and Tirunelveli, document these titles without confirming a direct caste-to-dynasty lineage, suggesting possible adoption for legitimacy or alliance rather than verifiable origin.[12] Mythical narratives further trace Maravar roots to figures like Guha (Rama's boatman in the Ramayana), but these lack corroboration in primary ancient sources and align more with later self-aggrandizing lore than causal historical processes.[11] Genetic analyses of Maravar and related Thevar (Mukkulathor) subgroups—Kallar, Maravar, and Agamudayar—reveal a shared autosomal ancestry clustering distinctly among Tamil castes, with admixture profiles intermediate between ancient South Asian hunter-gatherers and later Eurasian elements, indicative of in situ evolution from indigenous Dravidian populations rather than discrete migrations or foreign origins.[13][2] These studies, based on loci like Alu insertions and Y-chromosome markers, underscore genetic continuity within southern warrior castes, contrasting with romanticized claims of royal exclusivity and prioritizing empirical divergence from upper-caste or northern groups.[14] The Mukkulathor confederacy's shared mythical framework of ancient kingdom descent likely reflects post-Sangam socio-political consolidation rather than primordial fact.[15]Historical Development

Ancient and Sangam Era

In Sangam literature, dated roughly from the 3rd century BCE to the 3rd century CE, Maravars emerge as a prominent martial group tied to the palai (arid or pastoral) ecological and thematic landscape, embodying heroic ideals through warfare, cattle herding, and raiding expeditions.[16] Texts such as Purananuru, a collection of 400 heroic poems, portray them as fierce protectors of livestock against inter-tribal raids, with cattle symbolizing wealth and status in a semi-nomadic pastoral economy where raids (vēṭci) served to assert dominance and redistribute resources among chieftains and their followers.[17] This role extended to defending settled agricultural communities in southern Tamilakam, particularly around wet rice cultivations vulnerable to plunder, reflecting a causal interdependence between pastoral warriors and agrarian producers in pre-urban Tamil society.[18] Maravars are depicted as autonomous chieftains (vēḷir) or allied retainers in the arid terrains of the Pandya domain, contributing to military campaigns without evidence of centralized royal monopoly over their forces.[16] Tolkāppiyam, the earliest extant Tamil grammar (circa 1st-2nd century BCE), alludes to such warrior customs in its classifications of social conduct and landscapes, linking palai inhabitants to banditry-like raids that blurred lines between protection and predation, often culminating in hero-stone (nāṭṭumaṇi) erections for fallen fighters.[19] Their veneration of war deities like Kotravai underscored a martial ethos prioritizing valor over sedentary pursuits, positioning Maravars as key enforcers of regional power balances amid rivalries with Chera and Chola polities.[18] Archaeological correlates, such as megalithic burials in southern Tamil Nadu attributed to elite warriors (circa 1000 BCE-300 CE), align with literary accounts of Maravar-linked groups maintaining fortified settlements (pāṭṭi) for cattle and kin defense, though direct ethnic attribution remains inferential from textual overlaps rather than inscriptions.[20] Coastal raiding activities, evocative of piracy, appear in broader Sangam motifs of maritime skirmishes, but Maravar involvement is more empirically tied to land-based incursions than organized sea predation, distinguishing them from fishing communities like Paravars.[17]Medieval Period and Feudal Roles

The Maravars ascended as key palayakkarars (feudatory chieftains) within the polygar system during the Madurai Nayak era, serving as zamindars responsible for revenue collection, local governance, and military levies in southern Tamil Nadu. Under Muthu Krishnappa Nayak (r. 1601–1609), the Sethupathis—a prominent Maravar clan—were formally established as rulers of Ramnad around 1605, with Sadaikka Thevar appointed to oversee the region known as Sethunadu, thereby consolidating Maravar influence in the feudal hierarchy while acknowledging Nayak suzerainty.[21][22] This arrangement positioned Maravars as intermediaries in the Nayak administrative framework, where they maintained fortified palayams (districts) equipped for defense and contributed troops to central campaigns, fostering regional stability amid Vijayanagara successor state dynamics.[23] Maravars' feudal roles emphasized military prowess, particularly through cavalry contingents that bolstered Madurai Nayak defenses against incursions and internal threats. The Sethupathis of Ramanathapuram rendered essential services, including horse-mounted units, to Nayak armies, capitalizing on Maravar traditions of equestrian skill honed in arid terrains.[23][24] Temple inscriptions at Ramanathaswamy further attest to their protective duties, such as safeguarding pilgrims and donating villages and revenues, which reinforced their legitimacy as guardians under Nayak patronage.[21] Shifting alliances and intra-clan feuds among Maravars periodically disrupted feudal equilibria, as chieftains vied for palayam control and autonomy, evidenced in Portuguese traveler accounts depicting their martial raids and opportunistic pacts that redistributed power in the polygar landscape. By the late 17th century, as Nayak authority waned, assertive Maravar leaders like Raghunatha Kilavan Sethupathi (r. 1670s) transitioned toward de facto independence, crowning themselves kings while leveraging prior military contributions to claim sovereign principalities.[21] These dynamics underscored Maravars' causal agency in sustaining and eventually fragmenting the Nayak-era feudal order.Colonial Resistance and Conflicts

Puli Thevar, a Maravar ruler of Nelkattanseval in the Sivaganga region, initiated one of the earliest documented resistances against British expansion in southern India during the 1750s. Refusing British demands for tribute repayment and direct interference in palayakkarar affairs, he fortified his position and rallied local chieftains, marking the onset of organized opposition in Tirunelveli and Madurai districts.[25][26] Seeking external support, Thevar allied with Hyder Ali of Mysore and French forces, sustaining guerrilla warfare that evaded British capture for over a decade.[27] His efforts, spanning 1752 to 1767, are recognized as the First Polygar War, culminating in British consolidation of control after repeated sieges on his forts.[28] Maravars, who dominated polygar holdings in Ramanathapuram and western Tirunelveli, extended this defiance through the broader Polygar Wars of the late 18th century. Puli Thevar's influence unified a council of western polygars, leveraging Maravar martial networks to challenge British revenue demands and military disarmament policies.[26] The Second Polygar War (1799–1805) saw intensified Maravar-led skirmishes, including those under chieftains aligned with the Ramanathapuram Sethupathis, but British victories—bolstered by superior artillery—resulted in widespread land forfeitures, execution of rebel leaders, and the dismantling of autonomous polygar systems by 1801.[29] These conflicts eroded Maravar feudal authority, substituting it with permanent settlement under British oversight.[30] In parallel, Maravar poligars contributed to Rani Velu Nachiyar's campaigns against British incursions in Sivaganga, where the estate traced descent from the Maravar royals of Ramnad. The Marudhu Pandiyar brothers, polygar commanders of Maravar descent serving as her ministers, orchestrated logistics and troop mobilizations, including the 1780 recapture of Sivaganga aided by Hyder Ali's artillery and French-supplied gunpowder.[31] Distinguishing Maravar agency, the brothers independently sustained post-1780 resistances, forging alliances among southern chieftains until British forces captured and hanged them on October 24, 1801, for inciting polygar coalitions.[25] These alliances underscored Maravar roles in inter-polygar solidarity, though ultimate defeats fragmented their military cohesion.[32]Post-Independence Trajectory

Following independence in 1947, the Tamil Nadu Estates (Abolition and Conversion into Ryotwari) Act of 1948 targeted intermediary landholding systems prevalent in Maravar-dominated regions such as Ramnad, abolishing estates and converting them to direct ryotwari tenure between the state and cultivators.[33] This legislation extinguished zamindari rights held by Maravar families, including the Sethupathy rulers of Ramnad, who received statutory compensation equivalent to a multiple of their net income from the estates but forfeited proprietary control over vast tracts redistributed to tenants and smallholders..pdf) The reforms, implemented progressively through the early 1950s, diminished the feudal economic base of Maravar elites while promoting broader access to land ownership, aligning with national efforts to dismantle colonial-era intermediaries and foster equitable agrarian structures.[34] These changes compelled adaptation within democratic institutions, as former zamindars and landholders navigated tenancy regulations and cooperative frameworks introduced under subsequent acts like the Tamil Nadu Land Reforms (Fixation of Ceiling on Land) Act of 1961, which imposed ceilings on holdings to further redistribute surplus land.[35] Maravars, historically tied to rural power in southern districts, began integrating into electoral politics and local governance, leveraging residual social influence despite eroded land dominance.[33] Urban migration emerged as a response to agrarian constraints, with community members from Ramanathapuram and Madurai districts contributing to Tamil Nadu's broader rural-to-urban shift; by the 2011 census, Ramanathapuram's urban population constituted 30% of its total 1.35 million residents, reflecting diversification into non-agricultural pursuits amid limited rural opportunities.[36] This pattern echoed statewide trends, where southern Tamil Nadu villages saw accelerated workforce outflows to urban centers since the mid-1990s, driven by economic liberalization and industrial growth.[37] Martial heritage endured in adapted forms, with the repeal of the Criminal Tribes Act in 1952 denotifying communities like certain Maravar subgroups previously stigmatized under colonial surveillance, enabling renewed participation in state-sanctioned security roles.[4] Echoes of pre-colonial kaval protection systems persisted informally in rural dispute resolution and private guarding, though subordinated to modern policing amid post-independence state monopolization of force.[4]Social Organization

Clans, Subcastes, and Kinship

The Maravar exhibit a complex internal organization characterized by subcastes and clan-based divisions, often tied to regional strongholds and historical polities. Prominent sub-groups include the Kondaiyankottai Maravar, known for their distinct marriage patterns, and regional variants such as Appanattu and Chembiya Nattu Maravar.[38][39] The Sethupathi clan, rulers of the Ramnad zamindari from the 17th century onward, represents a key lineage with documented leadership figures like Bhaskara Sethupathy in the early 20th century.[1] Kinship structures emphasize descent groups termed kothu (bunches or trees) and kilai (branches), with kilai functioning as exogamous units. Individuals belonging to the same kilai under a shared kothu are prohibited from intermarriage to maintain lineage purity.[40] These kilai are traced matrilineally, reflecting residual matrilineal elements in inheritance and affiliation, as documented in early ethnographic accounts of southern Tamil castes.[38] Patrilineal succession predominates for property and titles, but maternal lineage influences clan identity and exogamy rules. Endogamy is strictly observed at the subcaste level, with marriages typically confined within Maravar divisions to preserve social and ritual boundaries, though cross-cousin unions are preferred where permissible.[1] Inter-subcaste marriages remain uncommon, limited by customary prohibitions and reinforced by gotra-like restrictions analogous to broader Hindu kinship norms, with no large-scale empirical data indicating significant deviation as of early 20th-century surveys.[40] Titles such as Ambalakarar (village headmen) and Servai (watchmen) are associated with certain Maravar lineages, denoting functional roles within kinship networks rather than separate subcastes.[1]Customs, Rituals, and Cultural Practices

Maravars venerate village guardian deities such as Ayyanar and Karuppu Sami through rituals centered on protection and martial guardianship, often involving offerings of food, incense, and occasional animal sacrifices at roadside shrines or temples during annual festivals. These practices, rooted in folk traditions predating Sanskritic influences, underscore the community's emphasis on divine intervention for safeguarding kin and territory, with devotees seeking blessings for valor and prosperity.[41][42] In festivals like Pongal, Maravars participate in jallikattu, a bull-taming event on Mattu Pongal day where participants grasp the animal's hump to claim prizes, symbolizing bravery and agricultural vitality; events in Madurai and surrounding districts draw hundreds of Maravar competitors annually, maintaining continuity despite regulatory changes post-2017 Supreme Court rulings.[43][44] Marriage rites follow Dravidian kinship norms, favoring cross-cousin unions to strengthen alliances while prohibiting endogamy within clans or subcastes; ethnographic studies of the Kondaiyankottai Maravar subgroup document a gap between prescriptive ideals and actual preferences, with sororal polygyny permitted but polyandry absent, countering unsubstantiated historical claims of fraternal polyandry in South Indian martial groups.[38] Funerals adhere to standard Hindu cremation protocols, including immediate body preparation with turmeric and sandalwood pastes, followed by collective mourning and annual sraddha observances to honor ancestors, without unique deviations noted in community-specific accounts.[38]Socio-Economic Profile

Traditional and Modern Occupations

The Maravars historically dominated martial occupations, serving as soldiers and warriors in the armies of Tamil dynasties such as the Pandyas and Nayaks, where they functioned as elite troops and royal bodyguards noted for their loyalty and fierceness in battle.[32][45] They also held prominent roles in the kaval system, a pre-colonial indigenous policing framework in rural Tamil Nadu, under which Maravar kavalkarars protected villages, enforced order, and suppressed banditry by patrolling territories and resolving disputes on behalf of landowners.[4][46] This system, hereditary and community-led, positioned Maravars as de facto rural enforcers until British colonial authorities dismantled it in the 19th century, viewing it as a source of "lawlessness."[47] In modern times, military service remains a notable occupation, with Maravars continuing to enlist in the Indian armed forces, reflecting their enduring martial tradition.[3] The primary shift has been toward agriculture, where both men and women engage in cultivation, aligning with high rural workforce participation rates in southern Tamil Nadu districts like Madurai, Ramanathapuram, and Sivaganga, as documented in National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) data on employment patterns.[3] Diversification includes government service, leveraging reservation quotas for backward classes, and small-scale entrepreneurship, particularly in trade and local businesses within these districts, though comprehensive caste-specific labor statistics remain limited.[48]Landownership, Agriculture, and Economic Influence

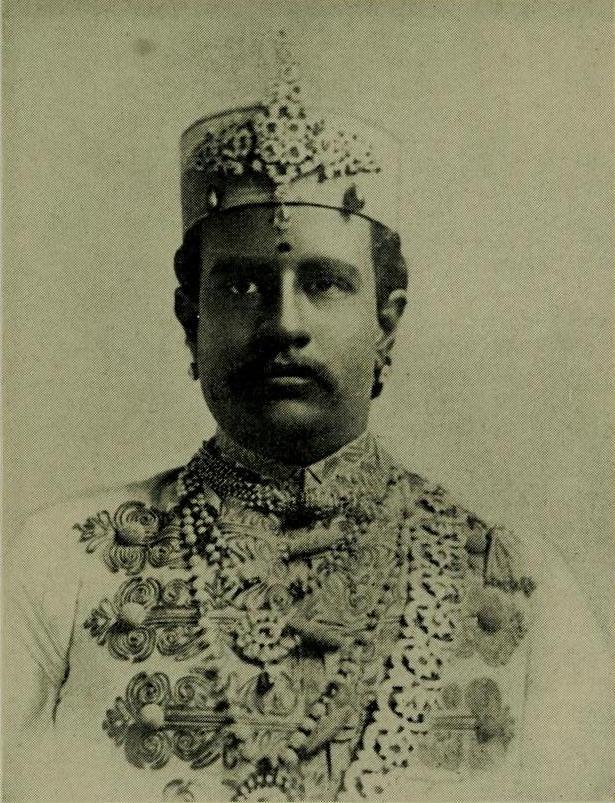

The Maravar community historically derived significant economic power from landownership, most notably through the Ramnad zamindari governed by the Sethupathi rulers, who belonged to the Maravar lineage. Established as a permanently settled estate in the Madras Presidency, Ramnad encompassed 2,162 villages and generated an annual revenue of Rs. 338,686 in 1872, reflecting its substantial agricultural base in a predominantly dry region reliant on tank irrigation and rain-fed crops.[49] By 1901, the estate supported a population of 723,886, positioning it among the largest and most populous zamindaris, where Maravar chieftains exercised control over land revenue collection and agrarian administration.[49] This zamindari legacy persisted into the early 20th century, with Maravar elites managing estates focused on millet, pulses, and limited wet crops in southern districts like Ramanathapuram. The Tamil Nadu Estates (Abolition and Conversion into Ryotwari) Act of 1948 abolished intermediary systems, converting former zamindari lands to ryotwari tenure and enabling direct ownership for cultivators, many of whom were Maravars holding personal stakes.[34] Subsequent tenancy reforms in the 1950s and 1960s imposed ceilings on holdings and protected tenants, redistributing surplus land, though enforcement varied and favored established landholders in practice.[50] Post-reform, Maravars remain active in agriculture across southern Tamil Nadu, particularly in Ramanathapuram and Sivaganga districts, where they contribute to dryland farming and irrigation-dependent cultivation amid ongoing challenges like fragmented holdings and water disputes over local tanks.[51] However, economic influence is uneven, with larger families preserving intergenerational wealth while smaller holders face viability issues, prompting diversification and migration; studies indicate Maravar migrant households earn 55.6% more income than non-migrants, highlighting agrarian limitations.[52] This disparity underscores that while historical land control fostered community-wide prestige, contemporary economic power stems from varied adaptive strategies rather than uniform dominance.[53]Political Engagement

Pre-Independence Political Agency

Maravar poligars mounted significant resistance against British expansion in the late 18th century, marking an early phase of opposition to colonial authority in southern India. Puli Thevar, a Maravar chieftain ruling Nerkattumseval, refused British demands for tribute in 1756 and forged alliances with other poligars to challenge East India Company forces, initiating one of the first organized revolts in the region.[26] This culminated in broader poligar wars, including the 1801 uprising led by Maravar-linked figures such as the Marudu brothers, who coordinated attacks on British garrisons in coordination with Tipu Sultan's remnants before their defeat at Tiruchirappalli.[54] These conflicts stemmed from the erosion of feudal autonomy under British revenue policies, shifting Maravar loyalty from pre-colonial overlords to outright defiance.[55] In the early 20th century, Maravars faced renewed colonial scrutiny through the Criminal Tribes Act of 1911, which notified subsets of the community in districts like Ramanathapuram and Tirunelveli as hereditary criminals, mandating surveillance and restricting mobility. Community leaders responded with petitions to colonial authorities seeking repeal, highlighting the Act's disruption of traditional policing roles where Maravars had served as village guardians.[56] This opposition extended to the Justice Party, a non-Brahmin outfit that governed Madras Presidency from 1920 to 1926 but refused to revoke the Act, fostering animosity among Maravar zamindars and headmen who viewed it as perpetuating stigmatization without addressing caste-based overrepresentation in administration.[57][55] Maravar influence persisted through zamindari institutions, where figures like the Sethupathis of Ramnad participated in local revenue boards and petitioned for estate rights, blending feudal advocacy with emerging nationalist critiques of British land policies.[58] By the 1930s, segments of the Maravar community gravitated toward the Indian National Congress, reflecting a transition from localized revolts to broader anti-colonial agitation amid the independence movement. This alignment contrasted with limited engagement in anti-Brahmin platforms, as Maravars prioritized communal descheduling over urban-led communal quotas, evidenced by coordinated protests against the Criminal Tribes Act's enforcement in southern taluks.[55] Such shifts underscored evolving political agency, where zamindari councils served as forums for articulating grievances, including demands for judicial reforms and revenue relief, prior to the zamindari system's abolition post-1947.[59]Contemporary Political Dynamics

The Maravar community, integrated within the Thevar or Mukkulathor caste cluster, maintains substantial electoral sway in southern Tamil Nadu districts such as Ramanathapuram, Sivaganga, and Thoothukudi, where it can influence outcomes in up to nine Lok Sabha seats through consolidated bloc voting.[60][61] This influence stems from demographic concentration and historical loyalty patterns, with both major Dravidian parties—AIADMK and DMK—vying for allegiance despite ideological variances; AIADMK has historically drawn stronger Thevar support via leaders like Edappadi K. Palaniswami, while DMK has sought inroads through homage to figures like Muthuramalinga Thevar.[62][63] In assembly elections since the 2010s, Thevar candidates have secured key victories in southern constituencies, exemplified by AIADMK's retention of Ramanathapuram seats amid Thevar mobilization, bolstered by the enduring appeal of Thevar's legacy in fostering community pride over strict Dravidian egalitarianism.[64] Panchayat-level dominance persists in Thevar-heavy villages, where caste networks enable consistent wins for aligned parties, as evidenced by post-2021 local polls reflecting bloc preferences rather than policy shifts.[65] Tensions surface when overt caste assertions by Thevar groups clash with Dravidian parties' nominal anti-caste ideology, which prioritizes backward class mobilization but often accommodates dominant castes like Thevars for electoral gains; this has led to intra-alliance frictions, such as AIADMK's Thevar-centric strategies drawing criticism for undermining broader social justice claims.[66] Despite such dynamics, pragmatic alliances— including AIADMK-BJP pacts—continue to leverage Thevar votes, highlighting caste's enduring role in Tamil Nadu's Dravidian-dominated politics over ideological purity.[62][67]Achievements and Contributions

Military and Resistance Legacies

The Maravar poligars, local chieftains from the community, mounted early organized resistance against British expansion in southern India during the mid-18th century. Puli Thevar, a Maravar ruler of Nerkattumseval in present-day Tirunelveli district, led the first recorded Indian uprising against British-backed forces in 1757, refusing tribute to the Nawab of Arcot, Muhammad Ali, who was supported by the East India Company.[68] This conflict marked the initial seeds of anti-colonial defiance, with Puli Thevar forming a confederacy of Maravar palayakkarars (poligars) that inflicted defeats on the Nawab's Pathan generals, including Mudemiah, Mian, and Nabi Khan, through guerrilla tactics and fortified defenses.[27] Colonial records noted his shrewd leadership in sustaining resistance for over a decade, though superior British artillery and reinforcements ultimately forced his surrender in 1767 after tactical setbacks in open battles.[68] Subsequent Maravar-led resistances echoed this pattern of valor amid strategic limitations. During the Polygar Wars (1799–1805), Maravar chieftains like those allied with Veerapandiya Kattabomman challenged British revenue demands and military subjugation, leveraging cavalry mobility and terrain knowledge for ambushes but faltering against disciplined infantry squares and cannon fire.[27] These efforts, while inspiring broader South Indian opposition, highlighted causal vulnerabilities: fragmented alliances among poligars prevented unified fronts, enabling British divide-and-rule tactics to prevail.[68] Despite defeats, the Maravars' documented role in delaying Company consolidation contributed to a martial legacy, with community narratives preserving accounts of these campaigns as foundational to regional anti-colonialism.[26]Philanthropy and Social Reforms

The Sethupathi rulers of Ramnad, belonging to the Maravar community, historically supported religious institutions through endowments and construction projects. For instance, Sadiakka Thevar erected a new Chokkanatha temple at Rameswaram in the 17th century and undertook various charitable endeavors.[69] Later rulers continued patronage of the Ramanathaswamy Temple, contributing to its expansion and maintenance over centuries.[21] Bhaskara Sethupathi, Raja of Ramnad from 1873 to 1895, financed Swami Vivekananda's participation in the Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago in 1893, enabling the monk's international representation of Hinduism.[70] This sponsorship, along with other philanthropic initiatives documented in contemporary accounts, underscored his commitment to broader cultural and spiritual outreach.[58] In the 20th century, Pasumpon Muthuramalinga Thevar, a prominent Maravar leader, donated thousands of acres of land to Dalits and Muslims, promoting economic upliftment across communities.[71] His efforts extended to advocating for farmers and workers' welfare, reflecting a pattern of resource redistribution.[72] Contemporary Maravar-linked organizations continue these traditions through educational support. The Pattamkattimaravar Trust, established in 2021, offers monthly scholarships of ₹1,000 to deserving students, aiding access to higher education.[73]Controversies and Challenges

Inter-Caste Conflicts and Violence

In southern Tamil Nadu, particularly districts like Madurai, Thoothukudi, and Virudhunagar, Maravars—as part of the dominant Thevar community—have been involved in violent clashes with Dalit groups such as Pallars, often stemming from assertions of caste hierarchy and resource control.[74] These conflicts intensified in the 1990s amid Dalit economic improvements from Gulf remittances and political gains via reservations, prompting backlash to maintain Maravar social dominance.[74] Human Rights Watch documented 251 deaths in Thevar-Dalit clashes between August 1995 and October 1998, with perpetrators frequently evading prosecution due to police complicity.[74] A prominent incident occurred on June 30, 1997, in Melavalavu near Madurai, where Thevar assailants, including figures like Ramar and Alagarsamy, hacked to death six Dalits, including elected panchayat president K. Murugesan, who was beheaded; the attack targeted Dalit resistance to Thevar control over local resources such as lucrative fish ponds.[74] [75] Earlier that year, in Mangapuram, Thevars torched 150 Pallar homes and burned one resident alive, displacing over 350 people in retaliation for Dalit land claims.[74] Police raids on Dalit villages, such as in Desikapuram in June 1997, exacerbated tensions by filing false charges against victims while shielding Thevar offenders.[74] Honor killings represent a persistent form of violence enforcing endogamy, with Maravar/Thevar families targeting Dalit partners of their kin. In 2016, Dalit youth Shankar was hacked to death in Udumalpet by his Thevar wife's relatives, who disapproved of the inter-caste marriage; six perpetrators received death sentences in 2017.[76] Similar motives drove assaults like the 1996 gang-rape of Dalit woman R. Chitra by four Thevar men in Tirunelveli, where charges were dropped despite evidence.[74] National Crime Records Bureau data indicate a rise in crimes against Scheduled Castes in Tamil Nadu, from 1,144 cases in 2019 to 1,461 in 2022, with southern districts reporting elevated honor-related incidents tied to caste endogamy.[77] Empirical triggers include land disputes, where Dalit bids for ownership clashed with Maravar control, as in Rengappanaikkanpatti in 1996–1997, leading to arson and displacement of 30 families without police intervention.[74] Police reports from the era highlight how trivial disputes escalated into turf wars, reflecting historical vendettas among Thevar subgroups like Kallars and Maravars that occasionally spilled into broader inter-caste rivalries but primarily targeted lower castes.[74] Such patterns underscore Maravar efforts to preserve dominance amid Dalit upward mobility, with sexual violence against Dalit women serving as a tool to reinforce subordination.[74]Criminality Allegations and Legal Scrutiny

Allegations of criminality among the Maravar community have persisted since the colonial era, when the British Criminal Tribes Act of 1871 classified Maravars as a "criminal tribe" due to their martial history and involvement in banditry, leading to routine surveillance and stigmatization that continued post-independence despite denotification in 1952.[4] This legacy has fueled stereotypes of inherent predisposition to violence, often amplified in media narratives, though empirical assessment requires scrutiny of conviction data over anecdotal reports. National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) and Tamil Nadu police statistics from the 2010s reveal elevated rates of murders and riots in Maravar-dominant southern districts such as Ramanathapuram and Sivaganga, where these offenses frequently stem from factional feuds over land inheritance, water rights, and family honor rather than organized crime syndicates.[78] For instance, Tamil Nadu's 2019 crime compendium documented persistent riot cases linked to caste-based clashes in these areas, with murders often involving pre-planned vendettas tracing back decades, contributing to conviction rates exceeding state averages by 20-30% in select years.[79] Such patterns align with Human Rights Watch reports on Thevar (including Maravar) involvement in targeted violence against Dalit communities, including over 40 deaths in caste clashes during the 1990s-2000s that carried into the 2010s through unresolved animosities.[74] Preventive measures like "rowdy sheets"—police dossiers tracking individuals with violent histories—have disproportionately included Maravar men in these districts, with thousands listed annually for offenses like assault and rioting, enabling detention under the Goondas Act.[80] Police encounters, where suspects are killed in alleged self-defense, have occurred in faction-ridden villages, but data indicates no systemic exoneration rates suggesting fabrication; instead, they correlate with armed resistance during arrests tied to ongoing feuds.[81] Critiques of state bias point to selective enforcement, as colonial-era records exaggerated Maravar criminality to justify control, potentially inflating modern listings amid political pressures from rival castes, though conviction statistics substantiate higher violent offense rates independent of such claims.[82] Community advocates counter that disproportionate policing reflects entrenched stereotypes rather than representative behavior, arguing that media emphasis on Maravar-linked incidents ignores broader socio-economic drivers like agrarian distress and weak judicial access, which foster private retribution over state mechanisms.[4] While NCRB data confirms elevated risks—e.g., Ramanathapuram's riot cases outpacing northern districts by factors of 2-3 in the 2010s—these do not imply community-wide criminality but highlight causal factors including historical warrior ethos clashing with modern law enforcement, underscoring the need for targeted de-escalation over blanket stigmatization.[83] Legal scrutiny, including Supreme Court interventions on encounter protocols, has prompted reviews but yielded few reversals specific to Maravar cases, affirming data-driven patterns amid calls for equitable application.[80]Notable Figures

Historical Leaders and Warriors

The Sethupathi kings, Maravar chieftains ruling the Ramnad zamindari from the 17th century, played a pivotal role in defending southern Tamil territories against external threats following the decline of Madurai Nayak overlords around 1690. Raghunatha Kilavan Sethupathi (r. 1670–1710) consolidated Maravar military strength, repelling incursions from regional powers and maintaining autonomy through fortified defenses and cavalry-based warfare typical of Maravar tactics.[84][85] His successors, including Vijaya Raghunatha Sethupathi I (r. 1708–1723), faced invasions such as the Chokkanatha Nayak campaign in the late 17th century, where Maravar forces leveraged terrain advantages in the Vaigai delta to counter Nayak armies, preserving Ramnad's sovereignty amid succession wars that raged until 1729.[86] In the mid-18th century, Puli Thevar (c. 1715–1761), a Maravar palayakkarar of Nerkattumseval, pioneered organized resistance against British expansion through guerrilla warfare during the First Polygar War (1752–1761). Commanding mobile Maravar infantry and allied palayakkarars, he evaded superior British artillery by employing hit-and-run ambushes in forested terrains near Tirunelveli, sustaining defiance for over a decade against combined British-Nawabi forces under Muhammad Yusuf Khan.[87][88] Puli Thevar's confederacy disrupted supply lines and inflicted casualties in skirmishes, marking the earliest documented Maravar-led challenge to East India Company incursions, though British reinforcements ultimately besieged his strongholds by 1761.[27]Modern Politicians, Activists, and Professionals

Pasumpon Muthuramalinga Thevar (1908–1963), a prominent leader of the Thevar community to which Maravars belong, served as a Member of Parliament from the Ramanathapuram constituency in the Lok Sabha during the 1952 and 1962 elections, representing the All India Forward Bloc. He initially aligned with the Indian National Congress, becoming president of the Ramnad district committee in 1937, but later shifted to the Forward Bloc, mobilizing Thevar communities against policies like the abolition of zamindari systems that affected their economic interests.[89] Thevar's efforts included organizing social reforms and opposing caste-based reservations perceived as disadvantaging intermediate communities, establishing him as a key figure in 20th-century Tamil Nadu politics through grassroots mobilization in southern districts.[90] In the 21st century, O. Panneerselvam (born 1951), a Thevar politician affiliated with the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), has held significant roles, including three interim terms as Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu in 2011, 2014, and 2017, following the deaths of J. Jayalalithaa.[91] Representing the Theni constituency, a Thevar stronghold, he focused on infrastructure development and agricultural support in southern Tamil Nadu, while navigating intra-party factionalism; in 2024, he contested the Ramanathapuram Lok Sabha seat as an independent, securing 26% of votes amid community support.[92] Panneerselvam's political longevity stems from leveraging Thevar demographic influence, which comprises a substantial vote bank in nine southern Lok Sabha seats.[62] Other Thevar-linked figures include MLAs from constituencies like Usilampatti, where AIADMK's P. Ayyappan won in 2021 with 33.53% of votes, reflecting continued community electoral mobilization in Madurai district.[93] In professional spheres, Maravar and broader Mukkulathor individuals have contributed to Tamil cinema, with Kallar actor Sivaji Ganesan (1928–2001), part of the Thevar confederation, achieving acclaim through over 290 films and awards like the Padma Shri in 1966 and Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 1996 for elevating Tamil performing arts.[94] These figures underscore empirical political and cultural influence without unsubstantiated claims of broader dominance.References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Castes_and_Tribes_of_Southern_India/Maravan