Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Watchmen

View on Wikipedia

Watchmen is a comic book limited series by the British creative team of writer Alan Moore, artist Dave Gibbons, and colorist John Higgins. It was published monthly by DC Comics in 1986 and 1987 before being collected in a single-volume edition in 1987. Watchmen originated from a story proposal Moore submitted to DC featuring superhero characters that the company had acquired from Charlton Comics. As Moore's proposed story would have left many of the characters unusable for future stories, managing editor Dick Giordano convinced Moore to create original characters instead.

Key Information

Moore used the story as a means of reflecting contemporary anxieties, deconstructing and satirizing the superhero concept, and making political commentary. Watchmen depicts an alternate history in which superheroes emerged in the 1940s and 1960s and their presence changed history so that the United States won the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal was never exposed. In 1985, the country is edging toward World War III with the Soviet Union, freelance costumed vigilantes have been outlawed and most former superheroes are in retirement or working for the government. The story focuses on the protagonists' personal development and moral struggles as an investigation into the murder of a government-sponsored superhero pulls them out of retirement.

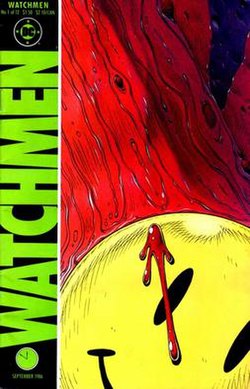

Gibbons uses a nine-panel grid layout throughout the series and adds recurring symbols such as a blood-stained smiley face. All but the last issue feature supplemental fictional documents that add to the series' backstory and the narrative is intertwined with that of another story, an in-story pirate comic titled Tales of the Black Freighter, which one of the characters reads. Structured at times as a nonlinear narrative, the story skips through space, time, and plot. In the same manner, entire scenes and dialogues have parallels with others through synchronicity, coincidence, and repeated imagery.

A commercial success, Watchmen has received critical acclaim both in the comics and mainstream press. Watchmen was recognized in Time's List of the 100 Best Novels as one of the best English language novels published since 1923. In a retrospective review, the BBC's Nicholas Barber described it as "the moment comic books grew up".[1] Moore opposed this idea, stating, "I tend to think that, no, comics hadn't grown up. There were a few titles that were more adult than people were used to. But the majority of comics titles were pretty much the same as they'd ever been. It wasn't comics growing up. I think it was more comics meeting the emotional age of the audience coming the other way."[2]

After several attempts to adapt the series into a feature film, director Zack Snyder's Watchmen was released in 2009. An episodic video game, Watchmen: The End Is Nigh, was released to coincide with the film's release.

DC Comics published Before Watchmen, a series of nine prequel miniseries, in 2012, and Doomsday Clock, a 12-issue limited series and sequel to the original Watchmen series, from 2017 to 2019 – both without Moore's or Gibbons' involvement. The second series integrated the Watchmen characters within the DC Universe. A standalone sequel, Rorschach by Tom King, began publication in October 2020. A television continuation to the original comic, set 34 years after the comic's timeline, was broadcast on HBO from October to December 2019 with Gibbons' involvement. Moore has expressed his displeasure with adaptations and sequels of Watchmen and asked it not be used for future works.[3]

Publication history

[edit]A single preview page for Watchmen, created by writer Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons, first appeared in the 1985 issue of DC Spotlight, the 50th anniversary special. The title was later published as a 12-issue maxiseries from DC Comics, cover-dated September 1986 to October 1987.[4]

| No. | Title | Publication date | On-sale date | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1

|

"At Midnight, All the Agents..." | September 1986 | May 13, 1986 | |

2

|

"Absent Friends" | October 1986 | June 10, 1986 | |

3

|

"The Judge of All the Earth" | November 1986 | July 8, 1986 | |

4

|

"Watchmaker" | December 1986 | August 12, 1986 | |

5

|

"Fearful Symmetry" | January 1987 | September 9, 1986 | |

6

|

"The Abyss Gazes Also" | February 1987 | October 14, 1986 | |

7

|

"A Brother to Dragons" | March 1987 | November 11, 1986 | |

8

|

"Old Ghosts" | April 1987 | December 9, 1986 | |

9

|

"The Darkness of Mere Being" | May 1987 | January 13, 1987 | |

10

|

"Two Riders Were Approaching..." | July 1987 | March 17, 1987 | |

11

|

"Look on My Works, Ye Mighty..." | August 1987 | May 19, 1987 | |

12

|

"A Stronger Loving World" | October 1987 | July 28, 1987 |

It was subsequently collected in 1987 as a DC Comics trade paperback that has had at least 24 printings as of March 2017;[17] another trade paperback was published by Warner Books, a DC sister company, in 1987.[18] In February 1988, DC published a limited-edition, slipcased hardcover volume, produced by Graphitti Design, that contained 48 pages of bonus material, including the original proposal and concept art.[19][20] In 2005, DC released Absolute Watchmen, an oversized slipcased hardcover edition of the series in DC's Absolute Edition format. Assembled under the supervision of Dave Gibbons, Absolute Watchmen included the Graphitti materials, as well as restored and recolored art by John Higgins.[21] That December DC published a new printing of Watchmen issue #1 at the original 1986 cover price of $1.50 as part of its "Millennium Edition" line.[22]

In 2012, DC published Before Watchmen, a series of nine prequel miniseries, with various creative teams producing the characters' early adventures set before the events of the original series.[23]

In the 2016 one-shot DC Universe: Rebirth Special, numerous symbols and visual references to Watchmen, such as the blood-splattered smiley face, and the dialogue between Doctor Manhattan and Ozymandias in the last issue of Watchmen, are shown.[24] Further Watchmen imagery was added in the DC Universe: Rebirth Special #1 second printing, which featured an update to Gary Frank's cover, better revealing the outstretched hand of Doctor Manhattan in the top right corner.[25][26] Doctor Manhattan later appeared in the 2017 four-part DC miniseries The Button serving as a direct sequel to both DC Universe Rebirth and the 2011 storyline "Flashpoint". Manhattan reappears in the 2017–19 twelve-part sequel series Doomsday Clock.[27]

Background and creation

[edit]"I suppose I was just thinking, 'That'd be a good way to start a comic book: have a famous super-hero found dead.' As the mystery unraveled, we would be led deeper and deeper into the real heart of this super-hero's world, and show a reality that was very different to the general public image of the super-hero."

In 1983, DC Comics acquired a line of characters from Charlton Comics.[29] During that period, writer Alan Moore contemplated writing a story that featured an unused line of superheroes that he could revamp, as he had done in his Miracleman series in the early 1980s. Moore reasoned that MLJ Comics' Mighty Crusaders might be available for such a project, so he devised a murder mystery plot which would begin with the discovery of the body of the Shield in a harbor. The writer felt it did not matter which set of characters he ultimately used, as long as readers recognized them "so it would have the shock and surprise value when you saw what the reality of these characters was".[28] Moore used this premise and crafted a proposal featuring the Charlton characters titled Who Killed the Peacemaker,[30] and submitted the unsolicited proposal to DC managing editor Dick Giordano.[31] Giordano was receptive to the proposal, but opposed the idea of using the Charlton characters for the story. After the acquisition of Charlton's Action Hero line, DC intended to use their upcoming Crisis on Infinite Earths event to fold them into their mainstream superhero universe. Moore said, "DC realized their expensive characters would end up either dead or dysfunctional." Instead, Giordano persuaded Moore to continue his project but with new characters that simply resembled the Charlton heroes.[32][33][34] Moore had initially believed that original characters would not provide emotional resonance for readers but later changed his mind. He said, "Eventually, I realized that if I wrote the substitute characters well enough, so that they seemed familiar in certain ways, certain aspects of them brought back a kind of generic super-hero resonance or familiarity to the reader, then it might work."[28]

Artist Dave Gibbons, who had collaborated with Moore on previous projects, recalled that he "must have heard on the grapevine that he was doing a treatment for a new miniseries. I rang Alan up, saying I'd like to be involved with what he was doing", and Moore sent him the story outline.[35] Gibbons told Giordano he wanted to draw the series Moore proposed and Moore approved.[36] Gibbons brought colorist John Higgins onto the project because he liked his "unusual" style; Higgins lived near the artist, which allowed the two to "discuss [the art] and have some kind of human contact rather than just sending it across the ocean".[30] Len Wein joined the project as its editor, while Giordano stayed on to oversee it. Both Wein and Giordano stood back and "got out of their way", as Giordano remarked later. "Who copy-edits Alan Moore, for God's sake?"[31]

After receiving the go-ahead to work on the project, Moore and Gibbons spent a day at the latter's house creating characters, crafting details for the story's milieu and discussing influences. The pair were particularly influenced by a Mad parody of Superman named "Superduperman"; Moore said: "We wanted to take Superduperman 180 degrees—dramatic, instead of comedic".[34] Moore and Gibbons conceived of a story that would take "familiar old-fashioned superheroes into a completely new realm";[37] Moore said his intention was to create "a superhero Moby Dick; something that had that sort of weight, that sort of density".[38] Moore came up with the character names and descriptions but left the specifics of how they looked to Gibbons. Gibbons did not sit down and design the characters deliberately, but rather "did it at odd times [...] spend[ing] maybe two or three weeks just doing sketches."[30] Gibbons designed his characters to make them easy to draw; Rorschach was his favorite to draw because "you just have to draw a hat. If you can draw a hat, then you've drawn Rorschach, you just draw kind of a shape for his face and put some black blobs on it and you're done."[39]

Moore began writing the series very early on, hoping to avoid publication delays such as those faced by the DC limited series Camelot 3000.[40] When writing the script for the first issue Moore said he realized "I only had enough plot for six issues. We were contracted for 12!" His solution was to alternate issues that dealt with the overall plot of the series with origin issues for the characters.[41] Moore wrote very detailed scripts for Gibbons to work from. Gibbons recalled that "[t]he script for the first issue of Watchmen was, I think, 101 pages of typescript—single-spaced—with no gaps between the individual panel descriptions or, indeed, even between the pages." Upon receiving the scripts, the artist had to number each page "in case I drop them on the floor, because it would take me two days to put them back in the right order", and used a highlighter pen to single out lettering and shot descriptions; he remarked, "It takes quite a bit of organizing before you can actually put pen to paper."[42] Despite Moore's detailed scripts, his panel descriptions would often end with the note "If that doesn't work for you, do what works best"; Gibbons nevertheless worked to Moore's instructions.[43] In fact, Gibbons only suggested one single change to the script – a compression of Ozymandias' narration while he was preventing a sneak attack by Rorschach – as he felt that the dialogue was too long to fit with the length of the action; Moore agreed and re-wrote the scene.[44] Gibbons had a great deal of autonomy in developing the visual look of Watchmen and frequently inserted background details that Moore admitted he did not notice until later.[38] Moore occasionally contacted fellow comics writer Neil Gaiman for answers to research questions and for quotes to include in issues.[41]

Despite his intentions, Moore admitted in November 1986 that there were likely to be delays, stating that he was, with issue five on the stands, still writing issue nine.[42] Gibbons mentioned that a major factor in the delays was the "piecemeal way" in which he received Moore's scripts. Gibbons said the team's pace slowed around the fourth issue; from that point onward the two undertook their work "just several pages at a time. I'll get three pages of script from Alan and draw it and then toward the end, call him up and say, 'Feed me!' And he'll send another two or three pages or maybe one page or sometimes six pages."[45] As the creators began to hit deadlines, Moore would hire a taxi driver to drive 50 miles and deliver scripts to Gibbons. On later issues the artist even had his wife and son draw panel grids on pages to help save time.[41]

Near the end of the project, Moore realized that the story bore some similarity to "The Architects of Fear", an episode of The Outer Limits television series.[41] The writer and Wein (an editor) argued over changing the ending and when Moore refused to give in, Wein quit the book. Wein explained, "I kept telling him, 'Be more original, Alan, you've got the capability, do something different, not something that's already been done!' And he didn't seem to care enough to do that."[46] Moore acknowledged the Outer Limits episode by referencing it in the series' last issue.[43]

Synopsis

[edit]Setting

[edit]Watchmen is set in an alternate reality that closely mirrors the contemporary world of the 1980s. The primary difference is the presence of superheroes. The point of divergence occurs in the year 1938. Their existence in this version of the United States is shown to have dramatically affected and altered the outcomes of real-world events such as the Vietnam War and the presidency of Richard Nixon.[47] In keeping with the realism of the series, although the costumed crimefighters of Watchmen are commonly called "superheroes", only one, named Doctor Manhattan, possesses any superhuman abilities.[48] The war in Vietnam ends with an American victory in 1971 and Nixon is still president as of October 1985 upon the repeal of term limits and the Watergate scandal not coming to pass. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan occurs approximately six years later than in real life.

When the story begins, the existence of Doctor Manhattan has given the U.S. a strategic advantage over the Soviet Union, which has dramatically increased Cold War tensions. Eventually, by 1977, superheroes grow unpopular among the police and the public, leading them to be outlawed with the passage of the Keene Act. While many of the heroes retired, Doctor Manhattan and another superhero, known as The Comedian, operate as government-sanctioned agents. Another named Rorschach continues to operate outside the law.[49]

Plot

[edit]In October 1985, New York City detectives investigate the murder of Edward Blake. With the police having no leads, costumed vigilante Rorschach decides to probe further. Rorschach deduces Blake to have been the true identity of "The Comedian", a costumed hero employed by the U.S. government, after finding his costume and signature smiley-face pin badge. Believing that Blake's murder could be part of a larger plot against costumed adventurers, Rorschach seeks out and warns four of his retired comrades: shy inventor Daniel Dreiberg, formerly the second Nite Owl; the superpowered and emotionally detached Jon Osterman, codenamed "Doctor Manhattan"; Doctor Manhattan's lover Laurie Juspeczyk, the second Silk Spectre; and Adrian Veidt, once the hero "Ozymandias", and now a successful businessman.

Dreiberg, Veidt, and Manhattan attend Blake's funeral, where Dreiberg tosses Blake's pin badge in his coffin before he is buried. Manhattan is later accused on national television of being the cause of cancer in friends and former colleagues. When the government takes the accusations seriously, Manhattan exiles himself to Mars. As the United States depends on Manhattan as a strategic military asset, his departure throws humanity into political turmoil, with the Soviets invading Afghanistan to capitalize on the United States' perceived weakness. Rorschach's concerns appear validated when Veidt narrowly survives an assassination attempt. Rorschach himself is framed for murdering a former supervillain named Moloch. While attempting to flee the scene of Moloch's murder, Rorschach is captured by police and unmasked as Walter Kovacs.

Neglected in her relationship with the once-human Manhattan, whose godlike powers have left him emotionally detached from ordinary people, and no longer kept on retainer by the government, Juspeczyk stays with Dreiberg. They begin a romance, don their costumes, and resume vigilante work as they grow closer together. With Dreiberg starting to believe some aspects of Rorschach's conspiracy theory, the pair take it upon themselves to break him out of prison. After looking back on his own personal history, Manhattan places the fate of his involvement with human affairs in Juspeczyk's hands. He teleports her to Mars to make the case for emotional investment. During the course of the argument, Juspeczyk is forced to come to terms with the fact that Blake, who once attempted to rape her mother (the original Silk Spectre), was actually her biological father, having fathered her in a second, consensual relationship. This discovery, reflecting the complexity of human emotions and relationships, reignites Manhattan's interest in humanity.

On Earth, Dreiberg and Rorschach find evidence that Veidt may be behind the conspiracy. Rorschach writes his suspicions about Veidt in his journal, which includes the full details of his investigation, and mails it to New Frontiersman, a local right-wing newspaper. When Rorschach and Dreiberg travel to Antarctica to confront Veidt at his private retreat, Veidt explains that he plans to save humanity from an impending nuclear war by staging a fake alien invasion and killing half the population of New York, forcing the United States and the Soviet Union to unite against a common enemy. He reveals that he murdered Blake after Blake discovered his plan, arranged for Doctor Manhattan's past associates to contract cancer to force him to leave Earth, staged the attempt on his own life to place himself above suspicion, and framed Rorschach for Moloch's murder to prevent him from discovering the truth. Horrified by Veidt's callous logic, Dreiberg and Rorschach vow to stop him, but Veidt reveals that he already enacted his plan before they arrived.

When Manhattan and Juspeczyk arrive back on Earth, they are confronted by mass destruction and death in New York, with a gigantic squid-like creature, created by Veidt's laboratories, dead in the middle of the city. Manhattan notices his prescient abilities are limited by tachyons emanating from the Antarctic and the pair teleport there. They discover Veidt's involvement and confront him. Veidt shows everyone news broadcasts confirming that the emergence of a new threat has indeed prompted peaceful co-operation between the superpowers; this leads almost all present to agree that concealing the truth is in the best interests of world peace. Rorschach refuses to compromise and leaves, intent on revealing the truth. As he is making his way back, he is confronted by Manhattan who argues that at this point, the truth can only hurt. Rorschach declares that Manhattan will have to kill him to stop him from exposing Veidt, which Manhattan duly does. Manhattan then wanders through the base and finds Veidt, who asks him if he did the right thing in the end. Manhattan cryptically responds that "nothing ever ends" before leaving Earth. Dreiberg and Juspeczyk go into hiding under new identities and continue their romance.

Back in New York, the editor at New Frontiersman asks his assistant to find some filler material from the "crank file", a collection of rejected submissions to the paper, many of which have not yet been reviewed. The series ends with the young man reaching toward the pile of discarded submissions, near the top of which is Rorschach's journal.

Characters

[edit]

With Watchmen, Alan Moore's intention was to create four or five "radically opposing ways" to perceive the world and to give readers of the story the privilege of determining which one was most morally comprehensible. Moore did not believe in the notion of "[cramming] regurgitated morals" down the readers' throats and instead sought to show heroes in an ambivalent light. Moore said, "What we wanted to do was show all of these people, warts and all. Show that even the worst of them had something going for them, and even the best of them had their flaws."[38]

- Walter Joseph Kovacs / Rorschach

- A vigilante who wears a white mask that contains a symmetrical but constantly shifting ink blot pattern, he continues to fight crime in spite of his outlaw status. Moore said he was trying to "come up with this quintessential Steve Ditko character—someone who's got a funny name, whose surname begins with a 'K,' who's got an oddly designed mask". Moore based Rorschach on Ditko's creation Mr. A; Ditko's Charlton character The Question also served as a template for creating Rorschach. Comics historian Bradford W. Wright described the character's world view as "a set of black-and-white values that take many shapes but never mix into shades of gray, similar to the ink blot tests of his namesake". Rorschach sees existence as random and, according to Wright, this viewpoint leaves the character "free to 'scrawl [his] own design' on a 'morally blank world'". Moore said he did not foresee the death of Rorschach until the fourth issue when he realized that his refusal to compromise would result in him not surviving the story.

- Adrian Veidt / Ozymandias

- Drawing inspiration from Alexander the Great, Veidt was once the superhero Ozymandias, but has since retired to devote his attention to the running of his own enterprises. Veidt is believed to be the smartest man on the planet. Ozymandias was based on Peter Cannon, Thunderbolt; Moore liked the idea of a character who "us[ed] the full 100% of his brain" and "[had] complete physical and mental control".[28] Richard Reynolds noted that by taking initiative to "help the world", Veidt displays a trait normally attributed to villains in superhero stories, and in a sense he is the "villain" of the series.[50] Gibbons noted, "One of the worst of his sins [is] kind of looking down on the rest of humanity, scorning the rest of humanity."[51]

- Daniel Dreiberg / Nite Owl II

- A retired superhero who utilizes owl-themed gadgets. Nite Owl was based on the Ted Kord version of the Blue Beetle. Paralleling the way Ted Kord had a predecessor, Moore also incorporated an earlier adventurer who used the name "Nite Owl", the retired crime fighter Hollis Mason, into Watchmen.[28] While Moore devised character notes for Gibbons to work from, the artist provided a name and a costume design for Hollis Mason he had created when he was twelve.[52] Richard Reynolds noted in Super Heroes: A Modern Mythology that despite the character's Charlton roots, Nite Owl's modus operandi has more in common with the DC Comics character Batman.[53] According to Klock, his civilian form "visually suggests an impotent, middle-aged Clark Kent."[54]

- Edward Blake / The Comedian

- One of two government-sanctioned heroes (along with Doctor Manhattan) who remains active after the Keene Act is passed in 1977 to ban superheroes. His murder, which occurs shortly before the first chapter begins, sets the plot of Watchmen in motion. The character appears throughout the story in flashbacks and aspects of his personality are revealed by other characters.[49] The Comedian was based on the Charlton Comics character Peacemaker, with elements of the Marvel Comics spy character Nick Fury added. Moore and Gibbons saw The Comedian as "a kind of Gordon Liddy character, only a much bigger, tougher guy".[28] Richard Reynolds described The Comedian as "ruthless, cynical, and nihilistic, and yet capable of deeper insights than the others into the role of the costumed hero."[49]

- Dr. Jon Osterman / Doctor Manhattan

- A superpowered being who is contracted by the United States government. Scientist Jon Osterman gained power over matter when he was caught in an "Intrinsic Field Subtractor" in 1959. Doctor Manhattan was based upon Charlton's Captain Atom, who in Moore's original proposal was surrounded by the shadow of nuclear threat. Captain Atom was the only hero with actual superpowers in Dick Giordano's Action Hero line at Charlton, just like Manhattan is the only character with actual superpowers in Watchmen.[55] However, the writer found he could do more with Manhattan as a "kind of a quantum super-hero" than he could have with Captain Atom.[28] In contrast to other superheroes who lacked scientific exploration of their origins, Moore sought to delve into nuclear physics and quantum physics in constructing the character of Dr. Manhattan. The writer believed that a character living in a quantum universe would not perceive time with a linear perspective, which would influence the character's perception of human affairs. Moore also wanted to avoid creating an emotionless character like Spock from Star Trek, so he sought for Dr. Manhattan to retain "human habits" and to grow away from them and humanity in general.[38] Gibbons had created the blue character Rogue Trooper and explained he reused the blue skin motif for Doctor Manhattan as it visualized electrical or atomic energy while still resembling human skin tonally and "reading as Jon Osterman's skin would've read, but in a different hue." Moore incorporated the color into the story, and Gibbons noted the rest of the comic's color scheme made Manhattan unique.[56] Moore recalled that he was unsure if DC would allow the creators to depict the character as fully nude, which partially influenced how they portrayed the character.[30] Gibbons wanted to be tasteful in depicting Manhattan's nudity, selecting carefully when full frontal shots would occur and giving him "understated" genitals—like a classical sculpture—so the reader would not initially notice it.[52]

- Laurie Juspeczyk / Silk Spectre II

- The daughter of Sally Jupiter (the first Silk Spectre, with whom she has a strained relationship) and The Comedian. Of Polish heritage, she had been the lover of Doctor Manhattan for years. While Silk Spectre was originally supposed to be the Charlton superheroine Nightshade, Moore was not particularly interested in that character. Once the idea of using Charlton characters was abandoned, Moore drew more from heroines such as Black Canary and Phantom Lady.[28] A University of Dayton student paper described Laurie as impulsive—"rarely using logic to think through situations"—but also as constantly standing by her belief that each human life matters, which contrasts with most other characters in Watchmen.[57]:

Art and composition

[edit]

Moore and Gibbons designed Watchmen to showcase the unique qualities of the comics medium and to highlight its particular strengths. In a 1986 interview, Moore said, "What I'd like to explore is the areas that comics succeed in where no other media is capable of operating", and emphasized this by stressing the differences between comics and film. Moore said that Watchmen was designed to be read "four or five times", with some links and allusions only becoming apparent to the reader after several readings.[38] Dave Gibbons notes that, "[a]s it progressed, Watchmen became much more about the telling than the tale itself. The main thrust of the story essentially hinges on what is called a macguffin, a gimmick ... So really the plot itself is of no great consequence ... it just really isn't the most interesting thing about Watchmen. As we actually came to tell the tale, that's where the real creativity came in."[58]

Gibbons said he deliberately constructed the visual look of Watchmen so that each page would be identifiable as part of that particular series and "not some other comic book".[59] He made a concerted effort to draw the characters in a manner different from that commonly seen in comics.[59] The artist tried to draw the series with "a particular weight of line, using a hard, stiff pen that didn't have much modulation in terms of thick and thin" which he hoped "would differentiate it from the usual lush, fluid kind of comic book line".[60] In a 2009 interview, Moore recalled that he took advantage of Gibbons' training as a former surveyor for "including incredible amounts of detail in every tiny panel, so we could choreograph every little thing".[61] Gibbons described the series as "a comic about comics".[45] Gibbons felt that "Alan is more concerned with the social implications of [the presence of super-heroes] and I've gotten involved in the technical implications." The story's alternate world setting allowed Gibbons to change details of the American landscape, such as adding electric cars, slightly different buildings, and spark hydrants instead of fire hydrants, which Moore said, "perhaps gives the American readership a chance in some ways to see their own culture as an outsider would". Gibbons noted that the setting was liberating for him because he did not have to rely primarily on reference books.[30]

Colorist John Higgins used a template that was "moodier" and favored secondary colors.[41] Moore stated that he had also "always loved John's coloring, but always associated him with being an airbrush colorist", which Moore was not fond of; Higgins subsequently decided to color Watchmen in European-style flat color. Moore noted that the artist paid particular attention to lighting and subtle color changes; in issue six, Higgins began with "warm and cheerful" colors and throughout the issue gradually made it darker to give the story a dark and bleak feeling.[30]

Structure

[edit]

Structurally, certain aspects of Watchmen deviated from the norm in comic books at the time, particularly the panel layout and the coloring. Instead of panels of various sizes, the creators divided each page into a nine-panel grid.[41] Gibbons favored the nine-panel grid system due to its "authority".[60] Moore accepted the use of the nine-panel grid format, which "gave him a level of control over the storytelling he hadn't had previously", according to Gibbons. "There was this element of the pacing and visual impact that he could now predict and use to dramatic effect."[58] Bhob Stewart of The Comics Journal mentioned to Gibbons in 1987, that the page layouts recalled those of EC Comics, in addition to the art itself, which Stewart felt particularly echoed that of John Severin.[45] Gibbons agreed that the echoing of the EC-style layouts "was a very deliberate thing", although his inspiration was rather Harvey Kurtzman,[44] but it was altered enough to give the series a unique look.[45] The artist also cited Steve Ditko's work on early issues of The Amazing Spider-Man as an influence,[62] as well as Doctor Strange, where "even at his most psychedelic [he] would still keep a pretty straight page layout".[39]

The cover of each issue serves as the first panel to the story. Gibbons said, "The cover of the Watchmen is in the real world and looks quite real, but it's starting to turn into a comic book, a portal to another dimension."[30] The covers were designed as close-ups that focused on a single detail with no human elements present.[38] The creators on occasion experimented with the layout of the issue contents. Gibbons drew issue five, titled "Fearful Symmetry", so the first page mirrors the last (in terms of frame disposition), with the following pages mirroring each other before the center-spread is (broadly) symmetrical in layout.[30]

The end of each issue, with the exception of issue twelve, contains supplemental prose pieces written by Moore. Among the contents are fictional book chapters, letters, reports, and articles written by various Watchmen characters. DC had trouble selling ad space in issues of Watchmen, which left an extra eight to nine pages per issue. DC planned to insert house ads and a longer letters column to fill the space, but editor Len Wein felt this would be unfair to anyone who wrote in during the last four issues of the series. He decided to use the extra pages to fill in the series' backstory.[43] Moore said, "By the time we got around to issue #3, #4, and so on, we thought that the book looked nice without a letters page. It looks less like a comic book, so we stuck with it."[30]

Tales of the Black Freighter

[edit]Watchmen features a story within a story in the form of Tales of the Black Freighter, a fictional comic book from which scenes appear in issues three, five, eight, ten, and eleven. The fictional comic's story, "Marooned", is read by a young man named Bernie who spends much of his time hanging out at a newsstand in New York City.[50] Moore and Gibbons conceived a pirate comic because they reasoned that since the characters of Watchmen experience superheroes in real life, "they probably wouldn't be at all interested in superhero comics."[63] Gibbons suggested a pirate theme, and Moore agreed in part because he is "a big Bertolt Brecht fan": the Black Freighter alludes to the song "Seeräuberjenny" ("Pirate Jenny") from Brecht's Threepenny Opera.[30] Moore theorized that since superheroes existed, and existed as "objects of fear, loathing, and scorn, the main superheroes quickly fell out of popularity in comic books, as we suggest. Mainly, genres like horror, science fiction, and piracy, particularly piracy, became prominent—with EC riding the crest of the wave." Moore felt "the imagery of the whole pirate genre is so rich and dark that it provided a perfect counterpoint to the contemporary world of Watchmen".[42] The writer expanded upon the premise so that its presence in the story would add subtext and allegory.[64] The supplemental article detailing the fictional history of Tales of the Black Freighter at the end of issue five credits real-life artist Joe Orlando as a major contributor to the series. Moore chose Orlando because he felt that if pirate stories were popular in the Watchmen universe that DC editor Julius Schwartz might have tried to lure the artist over to the company to draw a pirate comic book. Orlando contributed a drawing designed as if it were a page from the fake title to the supplemental piece.[42]

In "Marooned", a young mariner (called "The Sea Captain") journeys to warn his hometown of the coming of The Black Freighter, after he survives the destruction of his own ship. He uses the bodies of his dead shipmates as a makeshift raft and sails home, gradually descending into insanity. When he finally returns to his hometown, believing it to be already under the occupation of The Black Freighter's crew, he makes his way to his house and slays everyone he finds there, only to discover that the person he mistook for a pirate was in fact his wife. He returns to the seashore, where he realizes that The Black Freighter has not come to claim the town, but rather to claim him; he swims out to sea and climbs aboard the ship. According to Richard Reynolds, the mariner is "forced by the urgency of his mission to shed one inhibition after another." Just like Adrian Veidt, he "hopes to stave off disaster by using the dead bodies of his former comrades as a means of reaching his goal".[65] Moore stated that the story of The Black Freighter ends up specifically describing "the story of Adrian Veidt" and that it can also be used as a counterpoint to other parts of the story, such as Rorschach's capture and Dr. Manhattan's self-exile on Mars.[63]

Symbols and imagery

[edit]Moore named William S. Burroughs as one of his main influences during the conception of Watchmen. He admired Burroughs' use of "repeated symbols that would become laden with meaning" in Burroughs' only comic strip, "The Unspeakable Mr. Hart", which appeared in the British underground magazine Cyclops. Not every intertextual link in the series was planned by Moore, who remarked that "there's stuff in there Dave had put in that even I only noticed on the sixth or seventh read", while other "things [...] turned up in there by accident."[38]

A stained smiley face is a recurring image in the story, appearing in many forms. In The System of Comics, Thierry Groensteen described the symbol as a recurring motif that produces "rhyme and remarkable configurations" by appearing in key segments of Watchmen, notably the first and last pages of the series—spattered with blood on the first, and sauce from a hamburger on the last. Groensteen cites it as one form of the circle shape that appears throughout the story, as a "recurrent geometric motif" and due to its symbolic connotations.[66] Gibbons created a smiley face badge as an element of The Comedian's costume in order to "lighten" the overall design, later adding a splash of blood to the badge to imply his murder. Gibbons said the creators came to regard the blood-stained smiley face as "a symbol for the whole series",[60] noting its resemblance to the Doomsday Clock ticking up to midnight.[39] Moore drew inspiration from psychological tests of behaviorism, explaining that the tests had presented the face as "a symbol of complete innocence". With the addition of a blood splash over the eye, the face's meaning was altered to become simultaneously radical and simple enough for the first issue's cover to avoid human detail. Although most evocations of the central image were created on purpose, others were coincidental. Moore mentioned in particular that on "the little plugs on the spark hydrants if you turn them upside down, you discover a little smiley face".[38]

Other symbols, images, and allusions that appeared throughout the series often emerged unexpectedly. Moore mentioned that "[t]he whole thing with Watchmen has just been loads of these little bits of synchronicity popping up all over the place".[42] Gibbons noted an unintended theme was contrasting the mundane and the romantic,[44] citing the separate sex scenes between Nite Owl and Silk Spectre on his couch and then high in the sky on Nite Owl's airship.[45] In a book of the craters and boulders of Mars, Gibbons discovered a photograph of the Galle crater, which resembles a happy face, which they worked into an issue. Moore said, "We found a lot of these things started to generate themselves as if by magic", in particular citing an occasion where they decided to name a lock company the "Gordian Knot Lock Company".[42]

Themes

[edit]The initial premise of the series was to examine what superheroes would be like "in a credible, real world". As the story became more complex, Moore said Watchmen became about "power and about the idea of the superman manifest within society."[67] The title of the series refers to the question "Who will watch the watchmen themselves?", famously posed by the Roman satirist Juvenal (as "Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?"), although Moore was not aware of the phrase's classical origins until Harlan Ellison informed him.[68] Moore commented in 1987, "In the context of Watchmen, that fits. 'They're watching out for us, who's watching out for them?'"[30] The writer stated in the introduction to the Graffiti hardcover of Watchmen that while writing the series he was able to purge himself of his nostalgia for superheroes, and instead he found an interest in real human beings.[28]

Bradford Wright described Watchmen as "Moore's obituary for the concept of heroes in general and superheroes in particular."[48] Putting the story in a contemporary sociological context, Wright wrote that the characters of Watchmen were Moore's "admonition to those who trusted in 'heroes' and leaders to guard the world's fate". He added that to place faith in such icons was to give up personal responsibility to "the Reagans, Thatchers, and other 'Watchmen' of the world who supposed to 'rescue' us and perhaps lay waste to the planet in the process".[69] Moore specifically stated in 1986 that he was writing Watchmen to be "not anti-Americanism, [but] anti-Reaganism", specifically believing that "at the moment a certain part of Reagan's America isn't scared. They think they're invulnerable."[30] Before the series premiered, Gibbons stated: "There's no overt political message at all. It's a fantasy extrapolation of what might happen and if people can see things in it that apply to the real America, then they're reading it into the comic [...]."[70] While Moore wanted to write about "power politics" and the "worrying" times he lived in, he stated the reason that the story was set in an alternate reality was because he was worried that readers would "switch off" if he attacked a leader they admired.[34] Moore stated in 1986 that he "was consciously trying to do something that would make people feel uneasy."[30]

Citing Watchmen as the point where the comic book medium "came of age", Iain Thomson wrote in his essay "Deconstructing the Hero" that the story accomplished this by "developing its heroes precisely in order to deconstruct the very idea of the hero and so encouraging us to reflect upon its significance from the many different angles of the shards left lying on the ground".[71] Thomson stated that the heroes in Watchmen almost all share a nihilistic outlook, and that Moore presents this outlook "as the simple, unvarnished truth" to "deconstruct the would-be hero's ultimate motivation, namely, to provide a secular salvation and so attain a mortal immortality".[72] He wrote that the story "develops its heroes precisely in order to ask us if we would not in fact be better off without heroes".[73] Thomson added that the story's deconstruction of the hero concept "suggests that perhaps the time for heroes has passed", which he feels distinguishes "this postmodern work" from the deconstructions of the hero in the existentialism movement.[74] Richard Reynolds states that without any supervillains in the story, the superheroes of Watchmen are forced to confront "more intangible social and moral concerns", adding that this removes the superhero concept from the normal narrative expectations of the genre.[75] Reynolds concludes that the series' ironic self-awareness of the genre "all mark out Watchmen either as the last key superhero text, or the first in a new maturity of the genre".[76]

Geoff Klock eschewed the term "deconstruction" in favor of describing Watchmen as a "revisionary superhero narrative". He considers Watchmen and Frank Miller's Batman: The Dark Knight Returns to be "the first instances [...] of [a] new kind of comic book [...] a first phase of development, the transition of the superhero from fantasy to literature."[77] He elaborates by noting that "Alan Moore's realism [...] performs a kenosis towards comic book history [...] [which] does not ennoble and empower his characters [...] Rather, it sends a wave of disruption back through superhero history [...] devalue[ing] one of the basic superhero conventions by placing his masked crime fighters in a realistic world".[78] First and foremost, "Moore's exploration of the [often compromised] motives for costumed crimefighting sheds a disturbing light on past superhero stories, and forces the reader to reevaluate—to revision—every superhero in terms of Moore's kenosis—his emptying out of the tradition".[79] Klock relates the title to the quote by Juvenal to highlight the problem of controlling those who hold power and quoted repeatedly within the work itself.[80] The deconstructive nature of Watchmen is, Klock notes, played out on the page also as, "[l]ike Alan Moore's kenosis, [Veidt] must destroy, then reconstruct, in order to build 'a unity which would survive him.'"[81]

Moore has expressed dismay that "[t]he gritty, deconstructivist postmodern superhero comic, as exemplified by Watchmen [...] became a genre". He said in 2003 that "to some degree there has been, in the 15 years since Watchmen, an awful lot of the comics field devoted to these grim, pessimistic, nasty, violent stories which kind of use Watchmen to validate what are, in effect, often just some very nasty stories that don't have a lot to recommend them".[82] Gibbons said that while readers "were left with the idea that it was a grim and gritty kind of thing", he said in his view the series was "a wonderful celebration of superheroes as much as anything else".[83]

Publication and reception

[edit]

Watchmen was first mentioned publicly in the 1985 Amazing Heroes Preview.[84] When Moore and Gibbons turned in the first issue of their series to DC, Gibbons recalled, "What really clinched it [...] was [writer/artist] Howard Chaykin, who doesn't give praise lightly, and who came up and said, 'Dave what you've done on Watchmen is freaking A.'"[85] Speaking in 1986, Moore said, "DC backed us all the way [...] and have been really supportive about even the most graphic excesses".[30] To promote the series, DC Comics released a limited-edition badge ("button") display card set, featuring characters and images from the series. Ten thousand sets of the four badges, including a replica of the blood-stained smiley face badge worn by the Comedian in the story, were released and sold.[45] Mayfair Games introduced a Watchmen module for its DC Heroes Role-playing Game series that was released before the series concluded. The module, which was endorsed by Moore (who also provided story assistance),[86] adds details to the series' backstory by portraying events that occurred in 1966.[87]

Watchmen was published in single-issue form over the course of 1986 and 1987. The limited series was a commercial success, and its sales helped DC Comics briefly overtake its competitor Marvel Comics in the comic book direct market.[69] The series' publishing schedule ran into delays because it was scheduled with three issues completed instead of the six editor Len Wein believed were necessary. Further delays were caused when later issues each took more than a month to complete.[43] One contemporaneous report noted that although DC solicited issue #12 for publication in April 1987, it became apparent "it [wouldn't] debut until July or August".[42]

After the series concluded, the individual issues were collected and sold in trade paperback form. Along with Frank Miller's 1986 Batman: The Dark Knight Returns miniseries, Watchmen was marketed as a "graphic novel", a term that allowed DC and other publishers to sell similar comic book collections in a way that associated them with novels and dissociated them from comics.[88] As a result of the publicity given to the books like the Watchmen trade in 1987, bookstores and public libraries began to devote special shelves to them. Subsequently, new comics series were commissioned on the basis of reprinting them in a collected form for these markets.[89]

Watchmen received critical praise, both inside and outside of the comics industry. Time magazine, which noted that the series was "by common assent the best of breed" of the new wave of comics published at the time, praised Watchmen as "a superlative feat of imagination, combining sci-fi, political satire, knowing evocations of comics past and bold reworkings of current graphic formats into a dysutopian [sic] mystery story".[90] In 1988, Watchmen received a Hugo Award in the Other Forms category.[91] According to Gibbons, Moore had his award placed upside down in his garden and used it as a bird table.[92] Watchmen received the Locus Award for Best Non-fiction in 1988,[93] a point at which the Locus Awards did not have a category for illustrated works.

Dave Langford reviewed Watchmen for White Dwarf #96, and stated that "The modern myth of the Superhero is curiously powerful despite its usual silliness; Watchmen lovingly disassembles the mythology into bloodstained cogs and ratchets, concluding with the famous quotation Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?"[94]

Ownership disputes

[edit]Disagreements about the ownership of the story ultimately led Moore to sever ties with DC Comics.[95] Not wanting to work under a work for hire arrangement, Moore and Gibbons had a reversion clause in their contract for Watchmen. Speaking at the 1985 San Diego Comic-Con, Moore said: "The way it works, if I understand it, is that DC owns it for the time they're publishing it, and then it reverts to Dave and me, so we can make all the money from the Slurpee cups."[40] For Watchmen, Moore and Gibbons received eight percent of the series' earnings.[38] Moore explained in 1986 that his understanding was that when "DC have not used the characters for a year, they're ours."[30] Both Moore and Gibbons said DC paid them "a substantial amount of money" to retain the rights. Moore added, "So basically they're not ours, but if DC is working with the characters in our interests then they might as well be. On the other hand, if the characters have outlived their natural life span and DC doesn't want to do anything with them, then after a year we've got them and we can do what we want with them, which I'm perfectly happy with."[30]

Moore said he left DC in 1989 due to the language in his contracts for Watchmen and his V for Vendetta series with artist David Lloyd. Moore felt the reversion clauses were ultimately meaningless because DC did not intend to let the publications go out of print. He told The New York Times in 2006, "I said, 'Fair enough ... You have managed to successfully swindle me, and so I will never work for you again.'"[95] In 2000, Moore publicly distanced himself from DC's plans for a 15th anniversary Watchmen hardcover release as well as a proposed line of action figures from DC Direct. While DC wanted to mend its relationship with the writer, Moore felt the company was not treating him fairly in regard to his America's Best Comics imprint (launched under the WildStorm comic imprint, which was bought by DC in 1998; Moore was promised no direct interference by DC as part of the arrangement). Moore added, "As far as I'm concerned, the 15th anniversary of Watchmen is purely a 15th Anniversary of when DC managed to take the Watchmen property from me and Dave [Gibbons]."[96] Soon afterward, DC Direct canceled the Watchmen action-figure line, despite the company having displayed prototypes at the 2000 San Diego Comic-Con.[97]

Prequel projects

[edit]Moore stated in 1985 that if the limited series was well-received, he and Gibbons would possibly create a 12-issue prequel series called Minutemen featuring the 1940s superhero group from the story.[40] DC offered Moore and Gibbons chances to publish prequels to the series, such as Rorschach's Journal or The Comedian's Vietnam War Diary, as well as hinting at the possibility of other authors using the same universe. Tales of the Comedian's Vietnam War experiences were floated because The 'Nam was popular at the time, while another suggestion was, according to Gibbons, for a "Nite Owl/Rorschach team" (in the manner of Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased)). Neither man felt the stories would have gone anywhere, with Moore particularly adamant that DC not go forward with stories by other individuals.[98] Gibbons was more attracted to the idea of a Minutemen series because it would have "[paid] homage to the simplicity and unsophisticated nature of Golden Age comic books—with the added dramatic interest that it would be a story whose conclusion is already known. It would be, perhaps, interesting to see how we got to the conclusion."[44]

Two prequel stories were published as Watchmen: Who Watches the Watchmen? and Watchmen: Taking Out the Trash in 1987. These were modules to the DC Heroes role-playing game, with Taking Out the Trash being notable as the only Watchmen spin-off material with direct involvement by Alan Moore (he is credited with Special design and concepts contribution as well as co-writing the essay The World of the Watchmen with game author Ray Winninger).[99]

In 2010, Moore told Wired that DC offered him the rights to Watchmen back if he would agree to prequel and sequel projects. Moore said that "if they said that 10 years ago, when I asked them for that, then yeah it might have worked [...] But these days I don't want Watchmen back. Certainly, I don't want it back under those kinds of terms." DC Comics co-publishers Dan DiDio and Jim Lee responded: "DC Comics would only revisit these iconic characters if the creative vision of any proposed new stories matched the quality set by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons nearly 25 years ago, and our first discussion on any of this would naturally be with the creators themselves."[100] Following months of rumors about a potential Watchmen follow-up project, in February 2012 DC announced it was publishing seven prequel series under the "Before Watchmen" banner. Among the creators involved were writers J. Michael Straczynski, Brian Azzarello, Darwyn Cooke, and Len Wein, and artists Lee Bermejo, J. G. Jones, Adam Hughes, Andy Kubert, Joe Kubert, and Amanda Conner. Though Moore had no involvement with Before Watchmen, Gibbons supplied the project with a statement in the initial press announcement:

The original series of Watchmen is the complete story that Alan Moore and I wanted to tell. However, I appreciate DC's reasons for this initiative and the wish of the artists and writers involved to pay tribute to our work. May these new additions have the success they desire.[23]

Sequels

[edit]Comic book sequel: Doomsday Clock

[edit]The sequel to Watchmen, entitled Doomsday Clock, is part of the DC Rebirth line of comics, additionally continuing a narrative established with 2016's one-shot DC Universe: Rebirth Special and 2017's crossover The Button, both of which featured Doctor Manhattan in a minor capacity. The miniseries, taking place seven years after the events of Watchmen in November 1992, follows Ozymandias as he attempts to locate Doctor Manhattan alongside Reginald Long, the successor of Walter Kovacs as Rorschach, following the exposure and subsequent failure of his plan for peace and the subsequent impending nuclear war between the United States and Russia.[101] The series was revealed on May 14, 2017, with a teaser image displaying the Superman logo in the 12 o'clock slot of the clock depicted in Watchmen and the series title in the bold typeface used for Watchmen.[102] The first of a planned twelve issues was released on November 22, 2017.[103]

The story includes many DC characters but has a particular focus on Superman and Doctor Manhattan, despite Superman stated as being a fictional character in the original series—the series uses the plot element of the multiverse. Writer Geoff Johns felt like there was an interesting story to be told in Rebirth with Doctor Manhattan. He thought there was an interesting dichotomy between Superman—an alien who embodies and is compassionate for humanity—and Doctor Manhattan—a human who has detached himself from humanity. This led to over six months of debates among the creative team about whether to intersect the Watchmen universe with the DC Universe, through the plot element of alternate realities. He explained that Doomsday Clock was the "most personal and most epic, utterly mind-bending project" that he had worked on in his career.[102]

Television series sequel

[edit]HBO brought on Damon Lindelof to develop a Watchmen television show, which premiered on October 20, 2019.[104] Lindelof, a fan of the limited series, made the show a "remix" of the comic, narratively a sequel while introducing a new set of characters and story that he felt made the work unique enough without being a full reboot of the comic series.[105] Among its main cast are Regina King, Don Johnson, Tim Blake Nelson, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II, and Jeremy Irons. The television show takes place in 2019, 34 years after the end of the limited series, and is primarily set in Tulsa, Oklahoma. Due to liberal policies set by President Robert Redford to provide reparations to those affected by racial violence, white supremacist groups (following the writings of Rorschach) attack the police who enforce these policies, leading to laws requiring police to hide their identity and wear masks. This has allowed new masked crime fighters to assist the police against the supremacists. Doctor Manhattan, Adrian Veidt / Ozymandias, and Laurie Blake / Silk Spectre are central characters to the show's plot.

Adaptations

[edit]Film adaptation

[edit]There have been numerous attempts to make a film version of Watchmen since 1986, when producers Lawrence Gordon and Joel Silver acquired film rights to the series for 20th Century Fox.[106] Fox asked Alan Moore to write a screenplay based on his story,[107] but he declined, so the studio enlisted screenwriter Sam Hamm. Hamm took the liberty of re-writing Watchmen's complicated ending into a "more manageable" conclusion involving an assassination and a time paradox.[107] Fox put the project into turnaround in 1991,[108] and the project was moved to Warner Bros. Pictures, where Terry Gilliam was attached to direct and Charles McKeown to rewrite it. They used the character Rorschach's diary as a voice-over and restored scenes from the comic book that Hamm had removed.[107] Gilliam and Silver were only able to raise $25 million for the film (a quarter of the necessary budget) because their previous films had gone over budget.[107] Gilliam abandoned the project because he decided that Watchmen would have been unfilmable. "Reducing [the story] to a two or two-and-a-half hour film [...] seemed to me to take away the essence of what Watchmen is about," he said.[109] After Warner Bros. dropped the project, Gordon invited Gilliam back to helm the film independently. The director again declined, believing that the comic book would be better directed as a five-hour miniseries.[110]

In October 2001, Gordon partnered with Lloyd Levin and Universal Studios, hiring David Hayter to write and direct.[111] Hayter and the producers left Universal due to creative differences,[112] and Gordon and Levin expressed interest in setting up Watchmen at Revolution Studios. The project did not hold together at Revolution Studios and subsequently fell apart.[113] In July 2004, it was announced Paramount Pictures would produce Watchmen, and they attached Darren Aronofsky to direct Hayter's script. Producers Gordon and Levin remained attached, collaborating with Aronofsky's producing partner, Eric Watson.[114] Aronofsky left to focus on The Fountain and was replaced by Paul Greengrass.[115] Ultimately, Paramount placed Watchmen in turnaround.[116]

In October 2005, Gordon and Levin met with Warner Bros. to develop the film there again.[117] Impressed with Zack Snyder's work on 300, Warner Bros. approached him to direct an adaptation of Watchmen.[118] Screenwriter Alex Tse drew from his favorite elements of Hayter's script,[119] but also returned it to the original Cold War setting of the Watchmen comic. Similar to his approach to 300, Snyder used the comic book panel-grid as a storyboard and opted to shoot the entire film using live-action sets instead of green screens.[120] He extended the fight scenes,[121] and added a subplot about energy resources to make the film more topical.[122] Although he intended to stay faithful to the look of the characters in the comic, Snyder intended Nite Owl to look scarier,[120] and made Ozymandias' armor into a parody of the rubber muscle suits from the 1997 superhero film Batman & Robin.[44] After the trailer to the film premiered in July 2008, DC Comics president Paul Levitz said that the company had to print more than 900,000 copies of Watchmen trade collection to meet the additional demand for the book that the advertising campaign had generated, with the total annual print run expected to be over one million copies.[123] While 20th Century Fox filed a lawsuit to block the film's release, the studios eventually settled, with Warner agreeing to give Fox 8.5 percent of the film's worldwide gross, including from sequels and spin-offs in return.[115] The film was released to theaters in March 2009 to mixed reviews and grossed $185 million worldwide.

Tales of the Black Freighter was adapted as a direct-to-video animated feature from Warner Premiere and Warner Bros. Animation, which was released on March 24, 2009.[124] It was originally included in the screenplay for the Watchmen film,[125] but was cut due to budget restrictions,[126] as the segment would have added $20 million to the budget, because Snyder wanted to film it in a stylized manner reminiscent of 300.[124] Gerard Butler, who starred in 300, voices the Captain in the film, having been promised a role in Watchmen that never materialized.[127] Jared Harris voices his deceased friend Ridley, whom the Captain hallucinates is talking to him. Snyder had Butler and Harris record their parts together.[128] Snyder considered including the animated film in the final cut,[129] but the film was already approaching a three-hour running time.[124] The Tales of the Black Freighter was given standalone DVD release which also includes Under the Hood, a documentary detailing the characters' backstories, named after the character Hollis Mason's (the first Nite Owl) memoirs.[124][130] The film itself was released on DVD four months after Tales of the Black Freighter,[124] and in November 2009, a four-disc set was released as the "Ultimate Cut" with the animated film edited back into the main picture.[131] The director's cut and the extended version of Watchmen both include Tales of the Black Freighter on their DVD releases.[124]

Len Wein, the comic's editor, wrote a video game prequel entitled Watchmen: The End Is Nigh.[132]

Dave Gibbons became an adviser on Snyder's film, but Moore has refused to have his name attached to any film adaptations of his work.[133] Moore has stated he has no interest in seeing Snyder's adaptation; he told Entertainment Weekly in 2008 that "[t]here are things that we did with Watchmen that could only work in a comic, and were indeed designed to show off things that other media can't".[134] While Moore believes that David Hayter's screenplay was "as close as I could imagine anyone getting to Watchmen", he asserted he did not intend to see the film if it were made.[135]

Motion comic

[edit]In 2008, Warner Bros. Entertainment released Watchmen Motion Comics, a series of narrated animations of the original comic book. The first chapter was released for purchase in the summer of 2008 on digital video stores, such as iTunes Store.[136] A DVD compiling the full motion comic series was released in March 2009.[137]

Animated film

[edit]Warner Bros. announced in April 2017 that they would develop an R-rated animated film based on the comic book.[138] A teaser trailer was released on June 13, 2024, and revealed it to be a two-part film.[139][140]

Watchmen Chapter I received a digital release on August 13, 2024, and Blu-ray and 4K Ultra HD release on August 27, 2024, Watchmen Chapter II released on November 26, 2024.[141][142]

Arrowverse

[edit]The HBO version of the Watchmen was referenced in the Arrowverse's Crisis on Infinite Earths crossover.

Music

[edit]In 2025, Sevan Kirder's Thalassor released a concept album based on Watchmen, named "The End is Nigh"

Legacy

[edit]A critical and commercial success, Watchmen is highly regarded in the comics industry and is frequently considered by several critics and reviewers as comics' greatest series and graphic novel.[143][144][145][146] In addition to being one of the first major works to help popularize the graphic novel publishing format alongside The Dark Knight Returns,[147] Watchmen has also become one of the best-selling graphic novels ever published.[146][148] Watchmen was the only graphic novel to appear on Time's 2005 "All-Time 100 Greatest Novels" list,[149] where Time critic Lev Grossman described the story as "a heart-pounding, heartbreaking read and a watershed in the evolution of a young medium."[150] It later appeared on Time's 2009 "Top 10 Graphic Novels" list, where Grossman further praised Watchmen, proclaiming "It's way beyond cliché at this point to call Watchmen the greatest superhero comic ever written-slash-drawn. But it's true."[151] In 2008, Entertainment Weekly placed Watchmen at number 13 on its list of the best 50 novels printed in the last 25 years, describing it as "The greatest superhero story ever told and proof that comics are capable of smart, emotionally resonant narratives worthy of the label 'literature'."[152] The Comics Journal, however, ranked Watchmen at number 91 on its list of the Top 100 English-language comics of the 20th century.[153]

In Art of the Comic Book: An Aesthetic History, Robert Harvey wrote that, with Watchmen, Moore and Gibbons "had demonstrated as never before the capacity of the [comic book] medium to tell a sophisticated story that could be engineered only in comics".[154] In his review of the Absolute Edition of the collection, Dave Itzkoff of The New York Times wrote that the dark legacy of Watchmen, "one that Moore almost certainly never intended, whose DNA is encoded in the increasingly black inks and bleak storylines that have become the essential elements of the contemporary superhero comic book," is "a domain he has largely ceded to writers and artists who share his fascination with brutality but not his interest in its consequences, his eagerness to tear down old boundaries but not his drive to find new ones."[155] Alan Moore himself said his intentions with works like Marvelman and Watchmen were to liberate comics and open them up to new and fresh ideas, thus creating more diversity in the comics world by showing the industry what could be done with already existing concepts. Instead it had the opposite effect, confining the superhero comic to a "depressive ghetto of grimness and psychosis".[156] In 2009, Lydia Millet of The Wall Street Journal contested that Watchmen was worthy of such acclaim, and wrote that while the series' "vividly drawn panels, moody colors and lush imagery make its popularity well-deserved, if disproportionate", that "it's simply bizarre to assert that, as an illustrated literary narrative, it rivals in artistic merit, say, masterpieces like Chris Ware's 'Acme Novelty Library' or almost any part of the witty and brilliant work of Edward Gorey".[157]

Watchmen was one of the two comic books, alongside Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, that inspired designer Vincent Connare when he created the Comic Sans font.[158]

In 2009, Brain Scan Studios released the parody Watchmensch, a comic in which writer Rich Johnston chronicled "the debate surrounding Watchmen, the original contracts, the current legal suits over the Fox contract".[159]

Also in 2009, to coincide with the release of the Watchmen movie, IDW Publishing produced a parody one-shot comic titled Whatmen?![160]

Grant Morrison wrote a scene in Pax Americana (2014) where a child shoots his father in the head with his own gun, killing him. This was meant to symbolize Morrison's opinion about how the limited series had a negative impact on the superhero genre: "it's Watchmen's shot to the head of the American superhero."[161]

In September 2016, Hasslein Books published Watching Time: The Unauthorized Watchmen Chronology, by author Rich Handley. The book provides a detailed history of the Watchmen franchise.[162][163]

In December 2017, DC Entertainment published Watchmen: Annotated, a fully annotated black-and-white edition of the graphic novel, edited, with an introduction and notes by Leslie S. Klinger (who previously annotated Neil Gaiman's The Sandman for DC). The edition contains extensive materials from Alan Moore's original scripts and was written with the full collaboration of Dave Gibbons.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Barber, Nicholas (August 9, 2016). "Watchmen: The moment comic books grew up". BBC. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ^ "Watchmen author Alan Moore: 'I'm definitely done with comics' | Alan Moore | The Guardian". amp.theguardian.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2022.

- ^ Epstein, Adam (October 21, 2019). "HBO's "Watchmen" is great. Its comic creator Alan Moore wants nothing to do with it". Quartz. Archived from the original on April 4, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- ^ "Watchmen". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watchmen #1". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watchmen #2". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watchmen #3". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watchmen #4". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watchmen #5". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watchmen #6". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watchmen #7". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watchmen #8". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watchmen #9". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watchmen #10". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watchmen #11". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ "Watchmen #12". Grand Comics Database. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Watchmen (DC, 1987) at the Grand Comics Database. Archived May 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Watchmen (Warner Books, 1987) at the Grand Comics Database. Archived May 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Watchmen (DC, 1988) at the Grand Comics Database. Archived October 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Vanderplog, Scott (January 25, 2012). "Graphitti Watchmen HC". Comic Book Daily. Archived from the original on May 4, 2013..

- ^ Wolk, Douglas (October 18, 2005). "20 Years Watching the Watchmen". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ Millennium Edition: Watchmen #1 (March 2000) at the Grand Comics Database. Archived October 19, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Phegley, Kiel (February 1, 2012). "DC Comics to Publish 'Before Watchmen' Prequels". CBR. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ Yehl, Joshua (May 20, 2017). "DC Universe: Rebirth #1 Full Spoilers Leak Online" Archived September 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. IGN.

- ^ Arrant, Chris (May 27, 2016). "DC UNIVERSE: REBIRTH Gets Second Printing & Higher Cover Price". Newsarama. Archived from the original on May 30, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ Schedeen, Jesse (January 10, 2017). "17 Most Anticipated Comics of 2017" Archived April 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. IGN. Retrieved January 13, 2017

- ^ Moore, Rose (September 22, 2017). "Geoff Johns' Doomsday Clock Trailer: Watchmen Crossover Comic Explained" Archived February 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. Screen Rant.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Toasting Absent Heroes: Alan Moore discusses the Charlton-Watchmen Connection". Comic Book Artist. No. 9. August 2000. Archived from the original on January 13, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ^ Eury & Giordano 2003, p. 117.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "A Portal to Another Dimension: Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and Neil Gaiman". The Comics Journal #116 (July 1987). Archived from the original on February 9, 2013.

- ^ a b Eury & Giordano 2003, p. 124.

- ^ Kruse, Zack (February 2021). Mysterious Travelers: Steve Ditko and the Search for a New Liberal Identity. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-4968-3057-9. Archived from the original on September 9, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ Martone, Eric (December 12, 2016). Italian Americans: The History and Culture of a People. Abc-Clio. ISBN 978-1-61069-995-2. Archived from the original on September 9, 2023. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ a b c Jensen, Jeff (October 21, 2005). "Watchmen: An Oral History (2 of 6)". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2006.

- ^ "Get Under the Hood of Watchmen…". Titan Books (2008, date n.a.) Retrieved October 15, 2008. Archived from the original on August 2, 2008.

- ^ Eury & Giordano 2003, p. 110.

- ^ Kavanagh, Barry. "The Alan Moore Interview: Watchmen characters Archived January 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine". Blather.net. October 17, 2000. Retrieved on October 14, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Eno, Vincent (Richard Norris); Csawza, El (May–June 1988). "Vincent Eno and El Csawza Meet Comics Megastar Alan Moore". Strange Things Are Happening via JohnCoulthart.com. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Illustrating Watchmen Archived January 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine". WatchmenComicMovie.com. October 23, 2008. Retrieved on October 28, 2008.

- ^ a b c Heintjes, Tom. "Alan Moore On (Just About) Everything". The Comics Journal. March 1986.

- ^ a b c d e f Jensen, Jeff. "Watchmen: An Oral History (3 of 6)". Entertainment Weekly. October 21, 2005. Retrieved on October 8, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stewart, Bhob. "Synchronicity and Symmetry". The Comics Journal. July 1987.

- ^ a b c d Amaya, Erik. "Len Wein: Watching the Watchmen". Comic Book Resources. September 30, 2008. Retrieved on October 3, 2008. Archived August 9, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e "Watching the Watchmen with Dave Gibbons: An Interview". Comics Bulletin. n.d. Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Stewart, Bhob. "Dave Gibbons: Pebbles in a Landscape". The Comics Journal. July 1987.

- ^ Ho, Richard. "Who's Your Daddy??" Wizard. November 2004.

- ^ Wright 2001, p. 271.

- ^ a b Wright 2001, p. 272.

- ^ a b c Reynolds 1992, p. 106.

- ^ a b Reynolds 1992, p. 110.

- ^ "Talking With Dave Gibbons". WatchmenComicMovie.com. October 16, 2008. Retrieved on October 28, 2008. Archived January 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Kallies, Christy (July 1999). "Under the Hood: Dave Gibbons". SequentialTart.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- ^ Reynolds 1992, p. 32.

- ^ Klock 2002, p. 66.

- ^ "Kinowa, Western Scourge; Charlton's Pulp - Issuu". Archived from the original on June 20, 2023. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

- ^ "Watchmen Secrets Revealed". WatchmenComicMovie.com. November 3, 2008. Retrieved on November 5, 2008. Archived January 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Geiser, Lauren N. (February 2016). "Flawed Heroes, Flawless Villain". Line by Line: A Journal of Beginning Student Writing. 2 (2). University of Dayton: 3–4.

She repeatedly acts and speaks before she thinks, rarely using logic to think through situations; her impulsivity often buries her in situations that would not have been as bad had she rationally thought through them beforehand. [...] Laurie clearly believes in and promotes the dignity of human life, which contrasts with most other characters in Watchmen. Similarly, Laurie constantly stands by her beliefs that each human life matters, even when facing the arguments of Dr. Manhattan.

- ^ a b Salisbury 2000, p. 82.

- ^ a b Salisbury 2000, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Salisbury 2000, p. 80.

- ^ Rogers, Adam. "Legendary Comics Writer Alan Moore on Superheroes, The League, and Making Magic." Wired.com. February 23, 2009. Retrieved on February 24, 2009. Archived January 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Salisbury 2000, pp. 77–80.

- ^ a b Kavanagh, Barry. "The Alan Moore Interview: Watchmen, microcosms and details". Blather.net. October 17, 2000. Retrieved on October 14, 2008. Archived December 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Salisbury 2000, pp. 80–82.

- ^ Reynolds 1992, p. 111.

- ^ Groensteen, p. 152, 155

- ^ "The Craft: An Interview with Alan Moore". Engine Comics (published 2004). September 9, 2002. Archived from the original on February 17, 2005. Retrieved October 14, 2008.

- ^ Plowright, Frank. "Preview: Watchmen". Amazing Heroes #97 (June 15, 1986), p. 43

- ^ a b Wright 2001, p. 273.

- ^ Plowright, p. 54

- ^ Thomson 2005, p. 101.

- ^ Thomson 2005, p. 108.

- ^ Thomson 2005, p. 109.

- ^ Thomson 2005, p. 111.

- ^ Reynolds 1992, p. 115.

- ^ Reynolds 1992, p. 117.

- ^ Klock 2002, pp. 25, 26.

- ^ Klock 2002, p. 63.

- ^ Klock 2002, p. 65.

- ^ Klock 2002, p. 62.

- ^ Klock 2002, p. 75.

- ^ Robinson, Tasha. "Interviews: Alan Moore". AVClub.com. June 25, 2003. Retrieved on October 15, 2008. Archived December 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Salisbury 2000, p. 96.

- ^ Plowright, p. 42

- ^ Duin, Steve and Richardson, Mike. Comics: Between the Panels. Dark Horse Comics, 1998. ISBN 978-1-56971-344-0, pp. 460–461

- ^ "Exclusive: How Alan Moore Helped Create the Watchmen Role-Playing Game". 13th Dimension. December 14, 2019. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Gomez, Jeffrey. "Who Watches the Watchmen?". Gateways. June 1987.

- ^ Sabin 1996, p. 165.

- ^ Sabin 1996, pp. 165–167.

- ^ Cocks, Jay (January 25, 1988). "The Passing of Pow! and Blam!" Archived August 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. (2 of 2). Time. Retrieved on September 19, 2008.

- ^ 1988 Hugo Awards Archived April 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. The HugoAwards.com. Retrieved on September 22, 2008.