Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Matthew 13

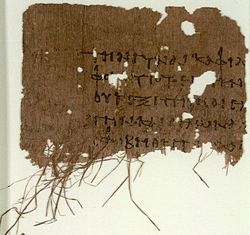

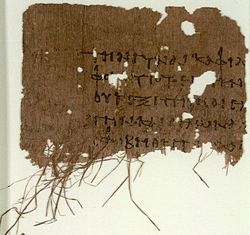

View on Wikipedia| Matthew 13 | |

|---|---|

Gospel of Matthew 13:55–56 on Papyrus 103, from c. AD 200 | |

| Book | Gospel of Matthew |

| Category | Gospel |

| Christian Bible part | New Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 1 |

Matthew 13 is the thirteenth chapter in the Gospel of Matthew in the New Testament section of the Christian Bible. This chapter contains the third of the five Discourses of Matthew, called the Parabolic Discourse, based on the parables of the Kingdom.[1] At the end of the chapter, Jesus is rejected by the people of his hometown, Nazareth.

Text

[edit]

The original text was written in Koine Greek. This chapter is divided into 58 verses.

Textual witnesses

[edit]Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter are:

- Papyrus 103 (~AD 200; extant verses 55–56)

- Codex Vaticanus (325–350)

- Codex Sinaiticus (330–360)

- Codex Bezae (~400)

- Codex Washingtonianus (~400)

- Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (~450)

- Codex Purpureus Rossanensis (6th century)

- Codex Petropolitanus Purpureus (6th century; extant verses 5–32, 42–58)

- Codex Sinopensis (6th century; extant verses 7–47, 54–58)

Old Testament references

[edit]New Testament references

[edit]Structure

[edit]Matthew 13 presents seven parables,[4] and two explanations of his parables. Overall, the verses in this chapter can be divided into groups (with cross references to parallel sections in the other gospels):

- 1–3: introduce Jesus preaching in a boat

- 3–9: Parable of the Sower (Mark 4:1–20; Luke 8:4–15)

- 10–17: reason for Parables

- 18–23: Parable of the Sower explained (Mark 4:1–20; Luke 8:4–15)

- 24–30: Parable of the Tares (Mark 4:26–29)

- 31–32: Parable of the Mustard Seed (Mark 4:30–32; Luke 13:19–21)

- 33–35: Parable of the Leaven (Luke 13:20–21)

- 36–43: Parable of the Tares explained

- 44: Parable of the Hidden Treasure

- 45–46: Parable of the Pearl

- 47–50: Parable of Drawing in the Net

- 51–52: conclusion[5]

- 53–58: Jesus is rejected in Nazareth (Mark 6:1–6; Luke 4:16–30)

Protestant theologian Heinrich Meyer identifies two groups of parables: the four first parables (up to Matthew 13:34) "were spoken in presence of the multitude, and the other three again within the circle of the disciples".[6] German liberal Protestant theologian David Strauss thought this chapter was "overwhelming with parables".[6] At the beginning of the chapter, Jesus sits in a ship or a boat on the Sea of Galilee and addresses the crowd who stand on the shore or the beach.[7] The Textus Receptus has inserted the definite article (Greek: τὸ πλοῖον, to ploion), suggesting that there was a boat kept waiting for him,[8] but other texts do not include the definite article and the Pulpit Commentary therefore argues that it was "wrongly inserted".[9]

Verses 51–52

[edit]- 51"Have you understood all these things?" Jesus asked.

- "Yes", they replied.

- 52 He said to them, "Therefore every teacher of the law who has become a disciple in the kingdom of heaven is like the owner of a house who brings out of his storeroom new treasures as well as old."[10]

These verses conclude the Parabolic Discourse and may be called a "comparative proverb".[11] Henry Alford describes them as a "solemn conclusion to the parables.[4] Johann Bengel suggests that Jesus would have been ready to explain the other parables if necessary, "but they understood them, if not perfectly, yet truly".[8] The reference to scribes, or teachers of the Jewish law, who became disciples reflects the Matthean gospel focus in particular; the Jerusalem Bible suggests that this reference may portray the evangelist himself.[12]

Verses 53–58

[edit]The final verses of this chapter see Jesus return to his home town, meaning Nazareth,[11] where he preaches in the synagogue and experiences the rejection of his "own people",[13] and his own country.

Dale Allison sees these verses and the following chapters as far as chapter 17 as recounting "the birth of the Church";[11] the Jerusalem Bible likewise holds that the same long section constitutes a narrative on the Church, followed by Matthew 18, which is often called the Discourse on the Church.[1]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Richard A. Jensen (1998), Preaching Matthew's Gospel: a narrative approach, ISBN 978-0-7880-1221-1. pp. 25 and 158.

- ^ a b Alexander, Loveday (2007). "62. Acts". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 1061. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, A. F. (1901). The Book of Psalms: with Introduction and Notes. The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges. Vol. Book IV and V: Psalms XC-CL. Cambridge: At the University Press. p. 839. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Alford, H., Greek Testament Critical Exegetical Commentary - Alford on Matthew 13, accessed 25 February 2021

- ^ Sub-heading in Jerusalem Bible

- ^ a b Meyer, H. A. W., Meyer's NT Commentary on Matthew 13, published 1880, accessed 13 January 2017

- ^ Matthew 13:2

- ^ a b Bengel, J. A., Bengel's Gnomon on Matthew 13, accessed 13 January 2017

- ^ Pulpit Commentary on Matthew 13, accessed 13 January 2017

- ^ Matthew 13:51–52

- ^ a b c Allison, D. Jr., Matthew in Barton, J. and Muddiman, J. (2001), The Oxford Bible Commentary, p. 862

- ^ Jerusalem Bible, footnote l at Matthew 13:52

- ^ Matthew 13:57: The Living Bible, Kenneth N. Taylor's paraphrase, accessed 29 November 2022

External links

[edit] Media related to Gospel of Matthew - Chapter 13 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gospel of Matthew - Chapter 13 at Wikimedia Commons- Matthew 13 King James Bible - Wikisource

- English Translation with Parallel Latin Vulgate

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- Multiple bible versions at Bible Gateway (NKJV, NIV, NRSV etc.)