Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Messier 84

View on Wikipedia| Messier 84 | |

|---|---|

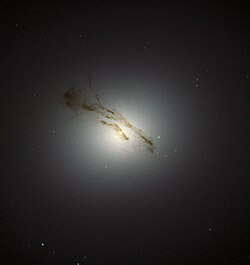

Galaxy Messier 84 in Virgo, imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope | |

| Observation data (J2000 epoch) | |

| Constellation | Virgo |

| Right ascension | 12h 25m 03.74333s[1] |

| Declination | +12° 53′ 13.1393″[1] |

| Redshift | 1,060±6 km/s[2] |

| Heliocentric radial velocity | 999[3] km/s |

| Distance | 54.9 Mly (16.83 Mpc)[3] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 9.1[4] |

| Absolute magnitude (V) | −22.41±0.10[5] |

| Characteristics | |

| Type | E1[5] |

| Apparent size (V) | 6.5′ × 5.6′[2] |

| Half-light radius (apparent) | 72.5″±6″[5] |

| Other designations | |

| M84, NGC 4374, PGC 40455, UGC 7494, VCC 763[6] | |

Messier 84 or M84, also known as NGC 4374, is a giant elliptical or lenticular galaxy in the constellation Virgo. Charles Messier discovered the object in 1781[a] in a systematic search for "nebulous objects" in the night sky.[7] It is the 84th object in the Messier Catalogue and in the heavily populated core of the Virgo Cluster of galaxies, part of the local supercluster.[8]

This galaxy has morphological classification E1, denoting it has flattening of about 10%. The extinction-corrected total luminosity in the visual band is about 7.64×1010 L☉. The central mass-to-light ratio is 6.5, which, to a limit, steadily increases away from the core. The visible galaxy is surrounded by a massive dark matter halo.[5]

Radio observations and Hubble Space Telescope images of M84 have revealed two jets of matter shooting out from its center as well as a disk of rapidly rotating gas and stars indicating the presence of a 1.5 ×109 M☉[9] supermassive black hole. It also has a few young stars and star clusters, indicating star formation at a very low rate.[10] The number of globular clusters is 1,775±150, which is much lower than expected for an elliptical galaxy.[11]

Viewed from Earth its half-light radius, relative angular size of its 50% peak of lit zone of the sky, is 72.5″, thus just over an arcminute.

Supernovae

[edit]Three supernovae have been observed in M84:

- SN 1957B (Type Ia, mag. 12.5) was discovered by Howard S. Gates on 28 April 1957, and independently by Dr. Giuliano Romano on 18 May 1957.[12][13][14]

- SN 1980I (Type Ia, mag. 14) was discovered by M. Rosker on 13 June 1980.[15][16] Historically, this supernova has been catalogued as belonging to M84, but it may have been in either neighboring galaxy NGC 4387 or M86.[17]

- SN 1991bg (Type Ia-pec, mag. 14) was discovered by Reiki Kushida on 3 December 1991.[18][19] This supernova has been studied extensively as a peculiar and underluminous Type Ia, and is now used as a template, with similar events being classified as Type Ia-91bg-like.[20]

This high rate of supernovae is rare for elliptical galaxies, which may indicate there is a population of stars of intermediate age in M84.[11]

See also

[edit]References and footnotes

[edit]- ^ a b Lambert, S. B.; Gontier, A.-M. (January 2009). "On radio source selection to define a stable celestial frame". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 493 (1): 317–323. Bibcode:2009A&A...493..317L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200810582.

- ^ a b "NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database". Results for NGC 4374. Retrieved 2006-11-14.

- ^ a b Tully, R. Brent; et al. (August 2016). "Cosmicflows-3". The Astronomical Journal. 152 (2): 21. arXiv:1605.01765. Bibcode:2016AJ....152...50T. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/152/2/50. S2CID 250737862. 50.

- ^ "Messier 84". SEDS Messier Catalog. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d Napolitano, N. R.; et al. (March 2011). "The PN.S Elliptical Galaxy Survey: a standard ΛCDM halo around NGC 4374?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 411 (3): 2035–2053. arXiv:1010.1533. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.411.2035N. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17833.x. S2CID 52221902.

- ^ "M 84". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 2009-12-17.

- ^ Jones, K. G. (1991). Messier's Nebulae and Star Clusters (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-37079-0.

- ^ Finoguenov, A.; Jones, C. (2002). "Chandra Observation of Low-Mass X-Ray Binaries in the Elliptical Galaxy M84". Astrophysical Journal. 574 (2): 754–761. arXiv:astro-ph/0204046. Bibcode:2002ApJ...574..754F. doi:10.1086/340997. S2CID 17551432.

- ^ Bower, G.A.; et al. (1998). "Kinematics of the Nuclear Ionized Gas in the Radio Galaxy M84 (NGC 4374)". Astrophysical Journal. 492 (1): 111–114. arXiv:astro-ph/9710264. Bibcode:1998ApJ...492L.111B. doi:10.1086/311109. S2CID 119456112.

- ^ Ford, Alyson; Bregman, J. N. (2012). "Detection of Ongoing, Low-Level Star Formation in Nearby Ellipticals". American Astronomical Society. 219: 102.03. Bibcode:2012AAS...21910203F.

- ^ a b Gómez, M.; Richtler, T. (February 2004). "The globular cluster system of NGC 4374". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 415 (2): 499–508. arXiv:1703.00313. Bibcode:2004A&A...415..499G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20034610.

- ^ Götz, W. (1958). "Supernova in NGC 4374 (= M 84)". Astronomische Nachrichten. 284 (3): 141–142. Bibcode:1958AN....284..141G. doi:10.1002/asna.19572840308.

- ^ Hansen, Julie M. Vinter (24 May 1957). "Circular No. 1600". Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. Observatory Copenhagen. Retrieved 30 November 2024.

- ^ "SN 1957B". Transient Name Server. IAU. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Kristian, J.; Rosker, M.; Smith, H. (1980). "Possible Supernova in Virgo Cluster". International Astronomical Union Circular (3492): 1. Bibcode:1980IAUC.3492....1K.

- ^ "SN 1980I". Transient Name Server. IAU. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Smith, H. A. (1981). "The spectrum of the intergalactic supernova 1980I". Astronomical Journal. 86: 998–1002. Bibcode:1981AJ.....86..998S. doi:10.1086/112975.

- ^ Kosai, H.; Kushida, R.; Kato, T.; Filippenko, A.; Newberg, H. (1991). "Supernova 1991bg in NGC 4374". International Astronomical Union Circular (5400): 1. Bibcode:1991IAUC.5400....1K.

- ^ "SN 1991bg". Transient Name Server. IAU. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Mazzali, Paolo A.; Hachinger, Stephan (2012). "The nebular spectra of the Type Ia supernova 1991bg: Further evidence of a non-standard explosion". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 424 (4): 2926. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.424.2926M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2012.21433.x.

- ^ on 18 March

External links

[edit]- StarDate: M84 Fact Sheet

- SEDS Lenticular Galaxy M84

- Messier 84 on WikiSky: DSS2, SDSS, GALEX, IRAS, Hydrogen α, X-Ray, Astrophoto, Sky Map, Articles and images

Messier 84

View on GrokipediaOverview and Discovery

General Description

Messier 84 (M84, NGC 4374) is a giant elliptical (E1) or lenticular (S0) galaxy situated in the constellation Virgo.[8][9] Located at a distance of approximately 60 million light-years, it exhibits an apparent visual magnitude of 10.1 and an absolute visual magnitude of −22.41 ± 0.10, yielding an extinction-corrected total luminosity of 7.64 × 10^{10} L_⊙ in the V band.[9] As a core member of the Virgo Cluster and the Virgo Supercluster, M84 has a half-light radius of 72.5 ± 6 arcseconds.[9] The galaxy is enveloped by a massive dark matter halo, with dynamical models indicating a virial mass on the order of 10^{13} M_⊙, which plays a key role in overall mass estimates and gravitational dynamics.[9] At its center lies a supermassive black hole.[9]Historical Discovery and Early Observations

Messier 84 was discovered on March 18, 1781, by the French astronomer Charles Messier during a systematic survey of nebulous objects in the constellation Virgo, marking it as the 84th entry in his renowned catalog of nebulae and star clusters intended to aid comet hunters in avoiding confusion with fixed celestial objects.[11] On the same night, Messier also identified several other members of what would later be recognized as the Virgo Cluster, though at the time these were simply recorded as faint, hazy patches without knowledge of their extragalactic nature.[12] Early follow-up observations came from the British astronomer William Herschel, who on April 17, 1784, described Messier 84 as a bright nebula of irregular figure, spanning about 5 arcminutes in its longest dimension and suspecting it to be composed of stars, using his 20-foot reflector telescope.[13] His son, John Herschel, later cataloged the object as h 1237 during sweeps from Slough in 1829, noting it as very bright and pretty large, round in shape with a mottled appearance and a sudden brightening toward the center, further emphasizing its nebulous character in his General Catalogue as GC 2930.[14] These descriptions highlighted its prominent, centralized brightness, distinguishing it from fainter or more diffuse nebulae observed at the time. Throughout the 19th century, improved telescopes allowed for more detailed scrutiny, with observers like William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse, using his 72-inch Leviathan reflector in the 1840s to examine similar bright nebulae, contributing to the growing recognition of Messier 84's smooth, elliptical form amid the Virgo region's crowded field.[15] This led to its informal classification as an elliptical nebula based on its rounded, featureless profile lacking spiral arms. In 1914, American astronomer Vesto Slipher at Lowell Observatory obtained the first spectroscopic observations of Messier 84, measuring a significant radial velocity of approximately +963 km/s, providing evidence of its recession and systemic motion relative to the Milky Way. Messier 84's placement within the Virgo Cluster was firmly established in Edwin Hubble's 1931 study with Milton Humason, which analyzed radial velocities of cluster members including Messier 84 to confirm their physical association and shared recession, supporting the emerging understanding of galaxy clusters as gravitationally bound systems. This work built on Slipher's spectra, integrating positional and velocity data to delineate the Virgo Cluster's structure, with Messier 84 identified as a core member.Physical Characteristics

Morphology and Dimensions

Messier 84, also known as NGC 4374, is classified as an E1 elliptical galaxy according to Hubble's tuning fork diagram, indicating a mild flattening with an axial ratio of about 0.9, or roughly 10% ellipticity.[16] However, its morphology is debated, with evidence suggesting it could be a lenticular S0 galaxy viewed nearly face-on; this interpretation arises from its low globular cluster specific frequency of 1.6 ± 0.3, which aligns more closely with S0 systems than typical ellipticals (where values exceed 3), as well as radially decreasing isophotal ellipticity that hints at underlying disk-like structure.[16] The galaxy spans a physical diameter of approximately 110,000 light-years, derived from its apparent angular size of 6.5 × 5.6 arcminutes and distance measurements placing it within the Virgo Cluster.[17] Dynamical analyses using planetary nebulae velocities reveal a total mass of approximately 3.5 × 10^{11} M_\odot within ~30 kpc (several effective radii), where the dark matter halo contributes significantly, comprising ~90% of the mass at large radii and following a Navarro-Frenk-White profile consistent with ΛCDM simulations.[18] Photometric studies of Messier 84's surface brightness profile demonstrate a classic de Vaucouleurs r^{1/4} law with a Sérsic index n ≈ 4, characteristic of elliptical galaxies, extending over multiple effective radii. Isophotal analysis from Hubble Space Telescope imaging in the ACS Virgo Cluster Survey highlights slightly boxy isophotes (a_4 ≈ -0.02) in the outer regions, with central deviations due to prominent dust lanes that obscure the nuclear area but do not alter the overall ellipsoidal form. Distance determinations for Messier 84 rely on Virgo Cluster calibrations, including surface brightness fluctuations (SBF) yielding a modulus of (m - M) ≈ 31.1, corresponding to 54.9 million light-years; this aligns with Cepheid variable distances to cluster spirals like NGC 4321 (≈16.8 Mpc) and Tully-Fisher relation applications to inclined Virgo members.[19][20]Stellar Content and Dynamics

Messier 84, classified as an elliptical galaxy, hosts a stellar population dominated by old, low-mass Population II stars, with minimal interstellar dust and gas content characteristic of such systems.[21] Integrated light spectroscopy reveals that the bulk of these stars formed rapidly in the early universe, with the stellar population exhibiting ages of approximately 10–12 billion years across the galaxy's effective radius.[21] Metallicity estimates from these analyses show a gradient, starting supersolar in the inner regions and declining to near-solar values outward, reflecting a hierarchical assembly history.[21] The internal dynamics of Messier 84 are primarily pressure-supported, as evidenced by a high stellar velocity dispersion of 250–300 km/s in the central and intermediate regions, with little rotational support (rotation velocities up to only ~20 km/s).[22][23] This dispersion profile, measured via integral-field spectroscopy, indicates anisotropic orbits sustaining the galaxy's structure without significant ordered rotation.[22] Star formation in Messier 84 is exceedingly low, with a current rate of approximately 2 × 10^{-5} M_\sun yr^{-1}, consistent with the quiescent nature of its old stellar content.[24] Ultraviolet observations from the Hubble Space Telescope detect faint signatures of minor recent activity, including a weak starburst around 125 million years ago that contributed roughly 1000 M_\sun of stars, likely triggered by intracluster medium interactions.[24]Central Nucleus

Supermassive Black Hole

Messier 84 harbors a supermassive black hole at its core with a mass of , determined through dynamical modeling of both stellar and ionized gas kinematics observed via Hubble Space Telescope (HST) spectroscopy.[25] This measurement refines earlier estimates by incorporating corrections for intrinsic velocity dispersion and asymmetric drift in the gas disk, yielding consistency with independent stellar dynamical analyses that place the mass at approximately .[26] The black hole's influence dominates the gravitational potential in the nuclear region, as evidenced by a rotating disk of stars and ionized gas extending to within approximately 70 pc of the center, where the orbital velocities follow a Keplerian rotation curve described by , with the black hole mass, the gravitational constant, and the radial distance.[27] The nuclear region also features a dusty disk suggestive of underlying molecular gas, contributing to the observed kinematics that trace the black hole's gravitational pull without significant contamination from other dynamical components. This structured rotation provides direct dynamical evidence for the black hole's presence and mass, as deviations from Keplerian motion would indicate alternative mass distributions, which are not observed.[28] Messier 84 exhibits low-level active galactic nucleus (AGN) activity classified as a Type 2 low-ionization nuclear emission-line region (LINER), powered by accretion onto the supermassive black hole at a low Eddington ratio. The LINER emission arises from photoionization by the accreting material and hot post-AGN gas, rather than higher-luminosity processes seen in quasars.[4] Compared to other supermassive black holes in Virgo Cluster ellipticals, such as the one in M87 with a mass of approximately , Messier 84's black hole is smaller by nearly an order of magnitude, reflecting variations in host galaxy properties and evolutionary histories.Jets and Radio Emissions

Messier 84 hosts prominent bipolar radio jets emanating from its central active nucleus, powered by the supermassive black hole, and extending approximately 10 kpc from the core.[29] These jets have been imaged in detail using the Very Large Array (VLA), revealing extended lobes characterized by synchrotron emission from relativistic electrons spiraling in magnetic fields.[29] The radio structure classifies Messier 84 as an FR I radio galaxy, with a total radio power of approximately W/Hz at 1.4 GHz, indicating a low-luminosity active galactic nucleus that drives these features without forming bright hotspots typical of more powerful FR II sources.[30] Recent observations with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory in 2023 have uncovered an H-shaped structure in the hot gas surrounding the jets, spanning about 40,000 light-years in height.[7] This morphology arises from cavities carved into the multimillion-degree intracluster medium by the jets, which displace and heat the gas as they propagate outward.[31] The X-ray data overlay well with VLA radio contours, confirming the jets' role in sculpting the surrounding plasma.[7] The jets exhibit relativistic dynamics, enabling them to inflate expansive bubbles in the intracluster medium and deposit energy that heats the gas on kiloparsec scales. Faraday rotation measures across the radio structure indicate ordered magnetic fields of approximately 10 µG within the magnetoionic medium enveloping the jets, influencing polarization patterns and suggesting a large-scale field reversal transverse to the jet axis.[32] These fields contribute to the synchrotron radiation observed, while the jets' interaction with the ambient medium modulates the overall radio morphology.[30]Role in the Virgo Cluster

Position and Interactions

Messier 84 is located at equatorial coordinates RA 12h 25m 03.7s, Dec +12° 53′ 13″ (J2000), placing it in the constellation Virgo near the border with Coma Berenices. As a central member of the Virgo Cluster, it resides approximately 17 Mpc (or 55 million light-years) from Earth and exhibits a radial velocity of 1015 km/s relative to the local standard of rest, consistent with the cluster's overall recession velocity of around 1000 km/s. Recent JWST observations indicate that M84 is located approximately 3 Mpc behind the main Virgo Cluster core centered on M87 (as of 2024).[33] This positioning situates Messier 84 in the dense core of the nearest major galaxy cluster, where gravitational influences from the intracluster medium and neighboring galaxies shape its environment. Messier 84 lies about 80 kpc from Messier 86, another giant elliptical galaxy in the Virgo core, forming part of Markarian's Chain—a linear arrangement of galaxies spanning the cluster center.[34] While direct tidal interactions between Messier 84 and Messier 86 appear limited, with no prominent HI gas tails detected for Messier 84 due to its low neutral hydrogen content typical of early-type galaxies, the warped dust lanes crossing its disk suggest past gravitational disturbances. These lanes, observed perpendicular to the radio axis, exhibit a twisted morphology potentially resulting from a historical merger event that contributed to its elliptical or lenticular form, as mergers are a common pathway for building such structures in cluster environments.[35] In the Virgo Cluster's hot intracluster medium, Messier 84 experiences ram-pressure stripping, particularly affecting its extended hot gas halo rather than cold gas reservoirs.[36] This process, driven by the galaxy's orbital motion through the dense X-ray-emitting gas, has likely removed much of the coronal gas during its infall, suppressing ongoing star formation and contributing to the quiescence observed in its stellar population. Dynamical modeling of Messier 84's orbit within the cluster potential relies on N-body simulations, which replicate the Virgo Cluster's mass distribution and predict bound, near-circular paths for central ellipticals like Messier 84, consistent with its stable position amid the cluster's hierarchical assembly.Globular Cluster System

Messier 84 hosts a rich globular cluster system with a total of 4301 ± 1201 clusters, far exceeding the Milky Way's approximately 150–200 clusters and consistent with expectations for a massive elliptical galaxy in a dense cluster environment. This population was quantified through Hubble Space Telescope (HST) imaging in the ACS Virgo Cluster Survey, which resolved clusters in the galaxy's central regions and extrapolated the total using supplementary ground-based and WFPC2 data. The clusters are primarily concentrated in the galaxy's extended halo, following a radial density profile that declines as ρ(r) ∝ r^{-1.09 ± 0.12} out to projected distances of about 6 arcmin (∼30 kpc), with no significant differences between subpopulations. The specific frequency S_N, defined as the number of globular clusters per 10^5 solar luminosities in the V-band, is 5.20 ± 1.45, aligning with values for other Virgo Cluster ellipticals like NGC 4472 and reflecting efficient cluster formation in massive early-type galaxies. In the z-band, S_{N,z} = 2.26 ± 0.63, accounting for the galaxy's redder stellar population.[37] The system comprises a bimodal color distribution indicative of metal-poor (blue) and metal-rich (red) subpopulations, with blue clusters dominating at a red fraction f_red = 0.11 (S_{N,z,blue} = 2.01 ± 0.51 and S_{N,z,red} = 0.24 ± 0.37). HST photometry in g and z bands reveals peak colors of B - R ≈ 1.11 for blue clusters and ≈ 1.36 for red, consistent with metallicities [Fe/H] ≈ -1.5 and ≈ 0, respectively.[38] These properties suggest formation in two epochs during the galaxy's early assembly, with ages estimated at 10–13 Gyr based on simple stellar population models assuming standard initial mass functions. Dynamical analyses of 38 globular cluster radial velocities, obtained via VLT/FORS2 spectroscopy out to projected radii of about 40 kpc, reveal kinematics that trace the underlying gravitational potential. The velocity dispersion profile shows a flat outer rotation and increasing dispersion, enabling isotropic mass modeling that indicates dark matter dominance beyond ∼20 kpc, with a total dynamical mass of ∼1.5 × 10^{12} M_⊙ within that radius—though this is lower than X-ray-derived estimates at larger scales. These studies highlight the globular clusters' role as tracers for constraining the dark matter halo profile in Messier 84.[39]Notable Phenomena

Observed Supernovae

Messier 84 has hosted two confirmed Type Ia supernovae, with a possible third (SN 1980I) whose association with the galaxy is uncertain, notable given the galaxy's low star formation rate which limits the frequency of such events.[1] The first, SN 1957B, was discovered on April 28, 1957, by Howard S. Gates at the University of Toronto, with an independent confirmation by Giuliano Romano on May 18, 1957, from his private observatory in Treviso, Italy. This Type Ia event reached a peak apparent magnitude of 12.5 and contributed to early calibrations of the cosmic distance ladder by providing a standard candle within the Virgo Cluster, whose distance was being refined through Cepheid variables and other methods at the time. SN 1980I was discovered on June 13, 1980, by M. Rosker at the Harvard College Observatory. Classified as a Type Ia supernova with a peak magnitude of 14, its position approximately 2 arcminutes from M84's center raised questions about its association, with spectroscopic analysis indicating it may be intergalactic or in a background galaxy rather than firmly within M84. Light curve studies confirmed its Type Ia characteristics, including a decline rate consistent with standard events, aiding in understanding transient sources in dense cluster environments. SN 1991bg, discovered on December 10, 1991, by Reiki Kushida at the Kiso Observatory (reported by H. Kosai), represents a peculiar subluminous Type Ia supernova with a peak magnitude of about 14. Photometric and spectroscopic observations revealed a slow post-peak decline and unusual spectral features, such as strong titanium absorption lines, making it a prototype for the 1991bg-like subclass of Type Ia events that are fainter and spectrally distinct from normal ones.[40] Theoretical models propose a sub-Chandrasekhar mass progenitor with a helium shell detonation triggering the carbon-oxygen core explosion, explaining its low luminosity and helium signatures.[41] These supernovae were detected through targeted optical patrols and early automated surveys, exemplified by facilities like the Katzman Automatic Imaging Telescope, which enhanced transient monitoring in nearby galaxies such as M84.Recent Imaging and Studies

Hubble Space Telescope (HST) imaging campaigns from the 1990s onward have provided high-resolution views of Messier 84's (NGC 4374) central regions, resolving a compact nuclear disk of ionized gas approximately 82 pc in diameter, aligned with prominent dust lanes that obscure the bright core.[42] These Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) observations revealed irregular dust features extending along the major axis at a position angle of about 58°, consistent with a warped or filamentary structure rather than a perfectly circular disk, suggesting dynamical disturbances from the central supermassive black hole.[42] In the 2000s and 2010s, Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) data from the ACS Virgo Cluster Survey further detailed the galaxy's stellar populations, identifying a rich system of globular clusters with bimodal color distributions indicative of metal-poor and metal-rich subpopulations, totaling several thousand objects that trace the galaxy's extended halo. Chandra X-ray Observatory observations spanning the 2000s to 2023 have mapped the multimillion-degree hot gas enveloping Messier 84, with temperatures around 0.7 keV and a total exposure exceeding 840 ks, revealing low-density cavities carved by relativistic jets from the central black hole.[31] These cavities, spanning scales of tens of kiloparsecs, form an H-shaped structure due to the jets' interaction with the intracluster medium, where the northern jet displaces approximately 500 Earth masses of gas per year, disrupting radial inflow and highlighting feedback mechanisms that regulate accretion.[31] The 2023 analysis confirmed that jet power influences gas dynamics more than gravitational settling in certain directions, with X-ray emission showing sharp edges at cavity boundaries.[31] Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) observations have detected circumnuclear molecular gas in Messier 84 via CO(2-1) emission, tracing a disk-like structure on scales of ~1 kpc with irregular morphology linked to the optical dust features observed by HST.[43] These data indicate inflows of cold molecular gas toward the nucleus, potentially fueling the active galactic nucleus, with kinematics suggesting rotational support amid turbulent motions.[43] Complementary Very Large Array (VLA) radio studies at centimeter wavelengths have imaged the propagating jets on kiloparsec scales, showing edge-brightened lobes and hotspots where synchrotron emission peaks, consistent with relativistic plasma advancing at near-light speeds and interacting with the surrounding medium. Integral Field Unit (IFU) spectroscopy with the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) on the Very Large Telescope has enabled spatially resolved mapping of ionized gas kinematics in Messier 84, revealing Hα velocity fields dominated by rotation in the nuclear disk, with dispersions indicating low turbulence (~50-100 km/s) and alignment between gas and stellar motions on arcsecond scales.[44] These observations, covering the central ~10 kpc, highlight decoupled gas components with blueshifted inflows along the jet axis, providing insights into multiphase gas dynamics driven by AGN feedback.[44]References

- https://science.[nasa](/page/NASA).gov/mission/hubble/science/explore-the-night-sky/hubble-messier-catalog/messier-84/