Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Messier 82

View on Wikipedia

| Messier 82 | |

|---|---|

A mosaic image taken by the Hubble Space Telescope of Messier 82, combining exposures taken with four colored filters that capture starlight from visible and infrared wavelengths as well as the light from the glowing hydrogen filaments | |

| Observation data (J2000 epoch) | |

| Constellation | Ursa Major |

| Right ascension | 09h 55m 52.9200s[1] |

| Declination | +69° 40′ 46.140″[1] |

| Redshift | 0.000897±0.000007[1] |

| Heliocentric radial velocity | 269±2 km/s[1] |

| Distance | 11.4–12.4 Mly (3.5–3.8 Mpc)[2] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 8.41[3][4] |

| Characteristics | |

| Type | I0[1] |

| Size | 12.52 kiloparsecs (40,800 light-years) (diameter; 25.0 mag/arcsec2 B-band isophote)[1][5] |

| Apparent size (V) | 11.2′ × 4.3′[1] |

| Notable features | Edge-on starburst galaxy |

| Other designations | |

| Cigar Galaxy, 3C 231, IRAS 09517+6954, NGC 3034, Arp 337, UGC 5322, MCG +12-10-011, PGC 28655, CGCG 333-008[1] | |

Messier 82 (also known as NGC 3034, Cigar Galaxy or M82) is a starburst galaxy approximately 12 million light-years away in the constellation Ursa Major. It is the second-largest member of the M81 Group, with the D25 isophotal diameter of 12.52 kiloparsecs (40,800 light-years).[1][5] It is about five times more luminous than the Milky Way and its central region is about one hundred times more luminous.[7] The starburst activity is thought to have been triggered by interaction with neighboring galaxy M81. As one of the closest starburst galaxies to Earth, M82 is the prototypical example of this galaxy type.[7][a] SN 2014J, a Type Ia supernova, was discovered in the galaxy on 21 January 2014.[8][9][10] In 2014, in studying M82, scientists discovered the brightest pulsar yet known, designated M82 X-2.[11][12][13]

In November 2023, a gamma-ray burst was observed in M82, which was determined to have come from a magnetar, the first such event detected outside the Milky Way (and only the fourth such event ever detected).[14][15]

Discovery

[edit]M82, with M81, was discovered by Johann Elert Bode in 1774; he described it as a "nebulous patch", this one about 3⁄4 degree away from the other, "very pale and of elongated shape". In 1779, Pierre Méchain independently rediscovered both objects and reported them to Charles Messier, who added them to his catalog.[16]

Structure

[edit]M82 was believed to be an irregular galaxy. In 2005, however, two symmetric spiral arms were discovered in near-infrared (NIR) images of M82. The arms were detected by subtracting an axisymmetric exponential disk from the NIR images. Even though the arms were detected in NIR images, they are bluer than the disk. The arms had been missed due to M82's high disk surface brightness, the nearly edge-on view of this galaxy (~80°),[7] and obscuration by a complex network of dusty filaments in its optical images. These arms emanate from the ends of the NIR bar and can be followed for the length of three disc scales. Assuming that the northern part of M82 is nearer to us, as most of the literature does, the observed sense of rotation implies trailing arms.[17]

Starburst region

[edit]In 2005, the Hubble Space Telescope revealed 197 young massive clusters in the starburst core.[7] The average mass of these clusters is around 200,000 solar masses, hence the starburst core is a very energetic and high-density environment.[7] Throughout the galaxy's center, young stars are being born 10 times faster than they are inside the entire Milky Way Galaxy.[18]

In the core of M82, the active starburst region spans a diameter of 500 pc. Four high surface brightness regions or clumps (designated A, C, D, and E) are detectable in this region at visible wavelengths.[7] These clumps correspond to known sources at X-ray, infrared, and radio frequencies.[7] Consequently, they are thought to be the least obscured starburst clusters from our vantage point.[7] M82's unique bipolar outflow (or 'superwind') appears to be concentrated on clumps A and C, and is fueled by energy released by supernovae within the clumps which occur at a rate of about one every ten years.[7]

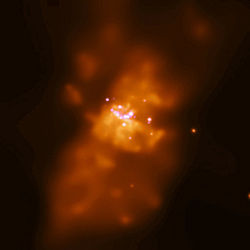

The Chandra X-ray Observatory detected fluctuating X-ray emissions about 600 light-years from the center of M82. Astronomers have postulated that this comes from the first known intermediate-mass black hole, of roughly 200 to 5000 solar masses.[19] M82, like most galaxies, hosts a supermassive black hole at its center.[20] This one has mass of approximately 3 × 107 solar masses, as measured from stellar dynamics.[20]

Unknown object

[edit]In April 2010, radio astronomers working at the Jodrell Bank Observatory of the University of Manchester in the UK reported an object in M82 that had started sending out radio waves, and whose emission did not look like anything seen anywhere in the universe before.[21]

There have been several theories about the nature of this object, but currently no theory entirely fits the observed data.[21] It has been suggested that the object could be an unusual "micro quasar", having very high radio luminosity yet low X-ray luminosity, and being fairly stable, it could be an analogue of the low X-ray luminosity galactic microquasar SS 433.[22] However, all known microquasars produce large quantities of X-rays, whereas the object's X-ray flux is below the measurement threshold.[21] The object is located at several arcseconds from the center of M82 which makes it unlikely to be associated with a supermassive black hole. It has an apparent superluminal motion of four times the speed of light relative to the galaxy center.[23][24] Apparent superluminal motion is consistent with relativistic jets in massive black holes and does not indicate that the source itself is moving above lightspeed.[23]

Starbursts

[edit]M82 is being physically affected by its larger neighbor, the spiral M81. Tidal forces caused by gravity have deformed M82, a process that started about 100 million years ago. This interaction has caused star formation to increase tenfold compared to "normal" galaxies.

M82 has undergone at least one tidal encounter with M81 resulting in a large amount of gas being funneled into the galaxy's core over the last 200 Myr.[7] The most recent such encounter is thought to have happened around 2–5×108 years ago and resulted in a concentrated starburst together with a corresponding marked peak in the cluster age distribution.[7] This starburst ran for up to ~50 Myr at a rate of ~10 M⊙ per year.[7] Two subsequent starbursts followed, the last (~4–6 Myr ago) of which may have formed the core clusters, both super star clusters (SSCs) and their lighter counterparts.[7]

Stars in M82's disk seem to have been formed in a burst 500 million years ago, leaving its disk littered with hundreds of clusters with properties similar to globular clusters (but younger), and stopped 100 million years ago with no star formation taking place in this galaxy outside the central starburst and, at low levels since 1 billion

years ago, on its halo. A suggestion to explain those features is that M82 was previously a low surface brightness galaxy where star formation was triggered due to interactions with its giant neighbor.[25]

Ignoring any difference in their respective distances from the Earth, the centers of M81 and M82 are visually separated by about 130,000 light-years.[26] The actual separation is 300+300

−200 kly.[27][2]

Supernovae

[edit]As a starburst galaxy, Messier 82 is prone to frequent supernova, caused by the collapse of young, massive stars. The first (although false) supernova candidate reported was SN 1986D, initially believed to be a supernova inside the galaxy until it was found to be a variable short-wavelength infrared source instead.[28]

The first confirmed supernova recorded in the galaxy was SN 2004am, discovered in March 2004 from images taken in November 2003 by the Lick Observatory Supernova Search. It was later determined to be a Type II supernova.[29] In 2008, a radio transient was detected in the galaxy, designated SN 2008iz and thought to be a possible radio-only supernova, being too obscured in visible light by dust and gas clouds to be detectable.[30] A similar radio-only transient was reported in 2009, although never received a formal designation and was similarly unconfirmed.[28]

Prior to accurate and thorough supernova surveys, many other supernovae likely occurred in previous decades. The European VLBI Network studied a number of potential supernova remnants in the galaxy in the 1980s and 90s. One supernova remnant displayed clear expansion between 1986 and 1997 that suggested it originally went supernova in the early 1960s, and two other remnants show possible expansion that could indicate an age almost as young, but could not be confirmed at the time.[31]

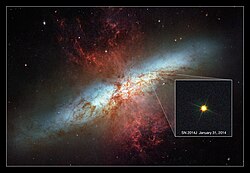

2014 supernova

[edit]On 21 January 2014 at 19.20 UT, a new distinct star was observed in M82, at apparent magnitude +11.7, by astrophysics lecturer Steve Fossey and four of his students, at the University of London Observatory. It had brightened to magnitude +10.9 two days later. Examination of earlier observations of M82 found the supernova to figure on the intervening day as well as on 15 through 20 January, brightening from magnitude +14.4 to +11.3; it could not be found, to limiting magnitude +17, from images caught of 14 January. It was initially suggested that it could become as bright as magnitude +8.5, well within the visual range of small telescopes and large binoculars,[32] but peaked at fainter +10.5 on the last day of the month.[33] Preliminary analysis classified it as "a young, reddened Type Ia supernova". The International Astronomical Union (IAU) has designated it SN 2014J.[34] SN 1993J was also at relatively close distance, in M82's larger companion galaxy M81. SN 1987A in the Large Magellanic Cloud was much closer. 2014J is the closest Type Ia supernova since SN 1972E.[8][9][10]

Gallery

[edit]-

Messier 82 imaged by amateur astronomer W4SM with 17" PlaneWave CDK astrograph

-

M82 cigar galaxy with its hydrogen emissions taken in France by amateur astrophotographer Anthony MICHEL[35]

See also

[edit]- List of Messier objects

- Baby Boom Galaxy – Specific starburst galaxy in the very distant universe

Notes

[edit]- ^ The irregular galaxy IC 10 in the Local Group is sometimes classified as a starburst galaxy, and hence is the closest such galaxy to Earth.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Results for object NGC 3034". NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- ^ a b Karachentsev, I. D.; Kashibadze, O. G. (2006). "Masses of the local group and of the M81 group estimated from distortions in the local velocity field". Astrophysics. 49 (1): 3–18. Bibcode:2006Ap.....49....3K. doi:10.1007/s10511-006-0002-6. S2CID 120973010.

- ^ "M 82". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ Armando, Gil de Paz; Boissier; Madore; Seibert; Boselli; et al. (2007). "The GALEX Ultraviolet Atlas of Nearby Galaxies". Astrophysical Journal Supplement. 173 (2): 185–255. arXiv:astro-ph/0606440. Bibcode:2007ApJS..173..185G. doi:10.1086/516636. S2CID 119085482.

- ^ a b De Vaucouleurs, Gerard; De Vaucouleurs, Antoinette; Corwin, Herold G.; Buta, Ronald J.; Paturel, Georges; Fouque, Pascal (1991). Third Reference Catalogue of Bright Galaxies. Bibcode:1991rc3..book.....D.

- ^ "Hubble views new supernova in Messier 82". ESA / HUBBLE. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Barker, S.; de Grijs, R.; Cerviño, M. (2008). "Star cluster versus field star formation in the nucleus of the prototype starburst galaxy M 82". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 484 (3): 711–720. arXiv:0804.1913. Bibcode:2008A&A...484..711B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200809653. S2CID 18885080.

- ^ a b "ATel #5786: Classification of Supernova in M82 as a young, reddened Type Ia Supernova". ATel. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Sudden Supernova in M82 Galaxy Rips Apart The Night Sky (A Bit)". Huffington Post. 22 January 2014.

- ^ a b Plait, Phil (22 January 2014). "KABOOM! Nearby Galaxy M82 Hosts a New Supernova!". Slate.

- ^ Tillman, Nola Taylor (8 October 2014). "Shockingly Bright Dead Star with a Pulse Is an X-ray Powerhouse". Space.com.

- ^ Chu, Jennifer (8 October 2014). "Researchers detect brightest pulsar ever recorded". Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ^ "NASA's NuSTAR Telescope Discovers Shockingly Bright Dead Star". NASA. 8 October 2014.

- ^ Mereghetti, Sandro; Rigoselli, Michela; Salvaterra, Ruben; Pacholski, Dominik Patryk; Rodi, James Craig; Gotz, Diego; Arrigoni, Edoardo; D'Avanzo, Paolo; Adami, Christophe; Bazzano, Angela; Bozzo, Enrico; Brivio, Riccardo; Campana, Sergio; Cappellaro, Enrico; Chenevez, Jerome; De Luise, Fiore; Ducci, Lorenzo; Esposito, Paolo; Ferrigno, Carlo; Ferro, Matteo; Israel, Gian Luca; Le Floc'h, Emeric; Martin-Carrillo, Antonio; Onori, Francesca; Rea, Nanda; Reguitti, Andrea; Savchenko, Volodymyr; Souami, Damya; Tartaglia, Leonardo; Thuillot, William; Tiengo, Andrea; Tomasella, Lina; Topinka, Martin; Turpin, Damien; Ubertini, Pietro (10 March 2024). "A magnetar giant flare in the nearby starburst galaxy M82". Astrophysics. 629 (2): 58–61. arXiv:2312.14645. Bibcode:2024Natur.629...58M. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07285-4. PMID 38658757.

- ^ Smith, Kiona (25 April 2024). "A Dead Star in a Nearby Galaxy Just Did Something Wild". Inverse. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ "Messier 82". SEDS.

- ^ Mayya, Y. D.; Carrasco, L.; Luna, A. (2005). "The Discovery of Spiral Arms in the Starburst Galaxy M82". Astrophysical Journal. 628 (1): L33 – L36. arXiv:astro-ph/0506275. Bibcode:2005ApJ...628L..33M. doi:10.1086/432644. S2CID 17576187.

- ^ "Happy Sweet Sixteen, Hubble Telescope!". Newswise. 20 April 2006. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

- ^ Patruno, A.; Portegies Zwart, S.; Dewi, J.; Hopman, C. (2006). "The ultraluminous X-ray source in M82: an intermediate-mass black hole with a giant companion". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 370 (1): L6 – L9. arXiv:astro-ph/0602230. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.370L...6P. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2006.00176.x. S2CID 10694200.

- ^ a b Gaffney, N. I.; Lester, D. F. & Telesco, C. M. (1993). "The stellar velocity dispersion in the nucleus of M82". Astrophysical Journal Letters. 407: L57 – L60. Bibcode:1993ApJ...407L..57G. doi:10.1086/186805.

- ^ a b c "Mysterious radio waves emitted from nearby galaxy". Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Joseph, T. D.; Maccarone, T. J.; Fender, R. P. (July 2011). "The unusual radio transient in M82: an SS 433 analogue?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 415 (1): L59 – L63. arXiv:1107.4988. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.415L..59J. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2011.01078.x. ISSN 1745-3933.

- ^ a b Muxlow, T. W. B.; Beswick, R. J.; Garrington, S. T.; Pedlar, A.; Fenech, D. M.; Argo, M. K.; Van Eymeren, J.; Ward, M.; Zezas, A.; Brunthaler, A.; Rich, R. M.; Barlow, T. A.; Conrow, T.; Forster, K.; Friedman, P. G.; Martin, D. C.; Morrissey, P.; Neff, S. G.; Schiminovich, D.; Small, T.; Donas, J.; Heckman, T. M.; Lee, Y. -W.; Milliard, B.; Szalay, A. S.; Yi, S. (2010). "Discovery of an unusual new radio source in the star-forming galaxy M82: Faint supernova, supermassive black hole or an extragalactic microquasar?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters. 404 (1): L109 – L113. arXiv:1003.0994. Bibcode:2010MNRAS.404L.109M. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2010.00845.x. S2CID 119302437.

- ^ O'Brien, Tim (14 April 2010). "Mystery object in Starburst Galaxy M82 – Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics". University of Manchester. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Divakara Mayya, Y.; Carrasco, Luis (2009). "M82 as a Galaxy: Morphology and Stellar Content of the Disk and Halo". Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica, Serie de Conferencias. 37: 44–55. arXiv:0906.0757. Bibcode:2009arXiv0906.0757D.

- ^ Declination separation of 36.87′ and Right Ascension separation of 9.5′ gives via Pythagorean theorem a visual separation of 38.07′; Average distance of 11.65 Mly × sin(38.07′) = 130,000 ly visual separation.

- ^ Separation = sqrt(DM812 + DM822 – 2 DM81 DM82 Cos(38.07′)) assuming the error direction is about the same for both objects.

- ^ a b "Messier Object 82". www.messier.seds.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "SN 2004am | Transient Name Server". wis-tns.weizmann.ac.il. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ "SN 2008iz | Transient Name Server". wis-tns.weizmann.ac.il. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Pedlar, A.; Muxlow, T. W. B.; Garrett, M. A.; Diamond, P.; Wills, K. A.; Wilkinson, P. N.; Alef, W. (August 1999). "VLBI observations of supernova remnants in Messier 82". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 307 (4): 761–768. Bibcode:1999MNRAS.307..761P. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.1999.02642.x.

- ^ Armstrong, Mark (23 January 2014). "Bright, young supernova outburst in Messier 82". Astronomy Now. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ MacRobert, Alan (17 February 2014). "Supernova in M82 Passes Its Peak". Sky & Telescope. Archived from the original on 14 February 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "UCL students discover a supernova". University College London. 22 January 2014. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ "M 82 - Cigar Galaxy".

External links

[edit]- M82, SEDS Messier pages

- M82 at Chandra

- SST: Galaxy on Fire!

- M82 at NASA/IPAC EXTRAGALACTIC DATABASE

- ESA/Hubble images of M82

- Messier 82 on WikiSky: DSS2, SDSS, GALEX, IRAS, Hydrogen α, X-Ray, Astrophoto, Sky Map, Articles and images

- M82 The Cigar Galaxy

- M82 images with 2 semiprofessional amateur-telescopes as a result of collaboration between 2 observatories

- M82 at Deep Space Map

![M82 cigar galaxy with its hydrogen emissions taken in France by amateur astrophotographer Anthony MICHEL[35]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/81/M82_Cigar_Galaxy.png/120px-M82_Cigar_Galaxy.png)