Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

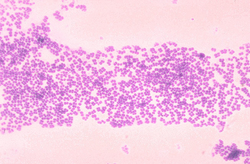

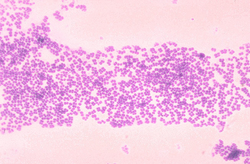

Micrococcus

View on Wikipedia

| Micrococcus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Micrococcus mucilaginosis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Kingdom: | Bacillati |

| Phylum: | Actinomycetota |

| Class: | Actinomycetes |

| Order: | Micrococcales |

| Family: | Micrococcaceae |

| Genus: | Micrococcus Cohn 1872 |

| Type species | |

| Micrococcus luteus (Schroeter 1872) Cohn 1872 (Approved Lists 1980)

| |

| Species | |

| |

Micrococcus, from Ancient Greek μικρός (mikrós), meaning "small", and κόκκος (kókkos), meaning "sphere", is a genus of bacteria in the Micrococcaceae family. Micrococcus occurs in a wide range of environments, including water, dust, and soil. Micrococci have Gram-positive spherical cells ranging from about 0.5 to 3 micrometers in diameter and typically appear in tetrads. They are catalase positive, oxidase positive, indole negative and citrate negative. Micrococcus has a substantial cell wall, which may comprise as much as 50% of the cell mass. The genome of Micrococcus is rich in guanine and cytosine (GC), typically exhibiting 65 to 75% GC-content. Micrococci often carry plasmids (ranging from 1 to 100 MDa in size) that provide the organism with useful traits.

Some species of Micrococcus, such as M. luteus (yellow) and M. roseus (red) produce yellow or pink colonies when grown on mannitol salt agar. Isolates of M. luteus have been found to overproduce riboflavin when grown on toxic organic pollutants like pyridine.[1]

Taxonomy

[edit]Hybridization studies from 1995 indicate that species within the genus Micrococcus are not closely related, showing as little as 50% sequence similarity.[2] This suggests that some Micrococcus species may, on the basis of ribosomal RNA analysis, eventually be re-classified into other microbial genera.

This section is missing information about dates of reclassification -- would inform interpretation of old sources from before these dates. (October 2023) |

The following species have been reclassified since then:

- "M. amylovorus" → Erwinia amylovora.

- "M. calcoaceticus" → Acinetobacter calcoaceticus.

- "M. cinereus" → Neisseria cinerea.

- "M. agilis" → Arthrobacter agilis.

- "M. denitrificans" → Paracoccus denitrificans

- "M. fulvus" → Myxococcus fulvus.

- "M. gallicidus" → Pasteurella multocida.

- "M. glutamicus" → Corynebacterium glutamicum.

- "M. halobius" → Nesterenkonia halobia.

- "M. halodenitrificans" → Halomonas halodenitrificans.

- "M. hyicus" → Staphylococcus hyicus.

- "M. indolicus" → Peptoniphilus indolicus.

- "M. kristinae" → Rothia kristinae.

- "M. lactis" → Neomicrococcus lactis.

- "M. meningitidis" → Neisseria meningitidis.

- "M. mucilaginosus" → Rothia mucilaginosa.

- "M. niger" → Peptococcus niger.

- "M. nishinomiyaensis" → Dermacoccus nishinomiyaensis.

- "M. nitrosus" → Nitrosococcus nitrosus.

- "M. pelletieri" → Actinomadura pelletieri.

- "M. phosphoreus" → Photobacterium phosphoreum.

- "M. pneumoniae" → Streptococcus pneumoniae.

- "M. prevotii" Foubert and Douglas 1948 → Anaerococcus prevotii.

- "M. roseus" → Kocuria rosea.

- "M. saccharolyticus" → Staphylococcus saccharolyticus.

- "M. sedentarius → Kytococcus sedentarius.

- "M. subflavus" → Neisseria subflava.

- "M. varians" → Kocuria varians

The following names were not included in the Approved Lists of 1980:

- "M. candicans"

- "M. cryophilus"

- "M. diversus"

- "M. prodigiosus"

- "M. radiodurans"

- "M. radioproteolyticus"

- "M. sodonensis"

In addition, GTDB (revision 214) indicates that Micrococcus terreus likely belongs in Citricoccus.[3]

Environmental

[edit]Micrococci have been isolated from human skin, animal and dairy products, and beer. They are found in many other places in the environment, including water, dust, and soil. M. luteus on human skin transforms compounds in sweat into compounds with an unpleasant odor. Micrococci can grow well in environments with little water or high salt concentrations, including sportswear made with synthetic fabrics.[4] Most are mesophiles; some, like Micrococcus antarcticus (found in Antarctica) are psychrophiles.

Though not a spore former, Micrococcus cells can survive for an extended period of time, both at refrigeration temperatures, and in nutrient-poor conditions such as sealed in amber.[5][6]

Pathogenesis

[edit]Micrococcus is generally thought to be a saprotrophic or commensal organism, though it can be an opportunistic pathogen, particularly in hosts with compromised immune systems, such as HIV patients.[7] It can be difficult to identify Micrococcus as the cause of an infection, since the organism is normally present in skin microflora, and the genus is seldom linked to disease. In rare cases, death of immunocompromised patients has occurred from pulmonary infections caused by Micrococcus. Micrococci may be involved in other infections, including recurrent bacteremia, septic shock, septic arthritis, endocarditis, meningitis, and cavitating pneumonia (immunosuppressed patients).

Industrial uses

[edit]Micrococci, like many other representatives of the Actinobacteria, can be catabolically versatile, with the ability to utilize a wide range of unusual substrates, such as pyridine, herbicides, chlorinated biphenyls, and oil.[8][9] They are likely involved in detoxification or biodegradation of many other environmental pollutants.[10] Other Micrococcus isolates produce various useful products, such as long-chain (C21-C34) aliphatic hydrocarbons for lubricating oils.

References

[edit]- ^ Sims GK, Sommers LE, Konopka A (1986). "Degradation of Pyridine by Micrococcus luteus Isolated from Soil". Appl Environ Microbiol. 51 (5): 963–968. Bibcode:1986ApEnM..51..963S. doi:10.1128/aem.51.5.963-968.1986. PMC 238995. PMID 16347070.

- ^ Stackebrandt, Erko, et al. "Taxonomic Dissection of the Genus Micrococcus: Kocuria gen. nov., Nesterenkonia gen. nov., Kytococcus gen. nov., Dermacoccus gen. nov., and Micrococcus Cohn 1872 gen. emend." International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 45.4 (1995): 682-692.

- ^ "GTDB GCF_900116905.1". gtdb.ecogenomic.org.

GTDB Taxonomy: d__Bacteria; p__Actinomycetota; c__Actinomycetia; o__Actinomycetales; f__Micrococcaceae; g__Citricoccus; s__Citricoccus terreus

- ^ "Why does my exercise clothing smell?". BBC News. 2016-08-31. Retrieved 2016-08-31.

- ^ Harrison AP, Pelczar MJ (1963). "Damage and Survival of Bacteria during Freeze-Drying and during Storage over a Ten-Year Period" (PDF). Journal of General Microbiology. 30 (3): 395–400. doi:10.1099/00221287-30-3-395. PMID 13952971. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ^ Greenblat CL, Baum J, Klein BY, Nachshon S, Koltunov V, Cano RJ (2004). "Micrococcus luteus – Survival in Amber". Microbial Ecology. 48 (1): 120–127. Bibcode:2004MicEc..48..120G. doi:10.1007/s00248-003-2016-5. PMID 15164240.

- ^ Smith K, Neafie R, Yeager J, Skelton H (1999). "Micrococcus folliculitis in HIV-1 disease". Br J Dermatol. 141 (3): 558–61. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03060.x. PMID 10583069.

- ^ Doddamani H, Ninnekar H (2001). "Biodegradation of carbaryl by a Micrococcus species". Curr Microbiol. 43 (1): 69–73. doi:10.1007/s002840010262. PMID 11375667.

- ^ Sims GK, O'loughlin EJ (1992). "Riboflavin Production during Growth of Micrococcus luteus on Pyridine". Appl Environ Microbiol. 58 (10): 3423–3425. Bibcode:1992ApEnM..58.3423S. doi:10.1128/aem.58.10.3423-3425.1992. PMC 183117. PMID 16348793.

- ^ Zhuang W, Tay J, Maszenan A, Krumholz L, Tay S (2003). "Importance of Gram-positive naphthalene-degrading bacteria in oil-contaminated tropical marine sediments". Lett Appl Microbiol. 36 (4): 251–7. doi:10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01297.x. PMID 12641721.